Delmarva Public Radio / Creative Commons

06.22.2017

New legislation in the US state of Florida will impose strict mandatory minimum sentences for people found possessing fentanyl, while people who sell it to those who later overdose can now be charged with murder, and thus face the death penalty.

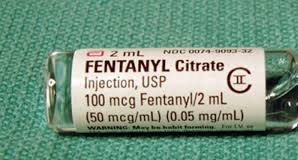

Controlled Substances/House Bill 477 (HB 477) was signed into law on 14 June by Rick Scott, the governor of Florida. The legislation is primarily targeted at curbing the use of fentanyl, a powerful opioid – estimated to be 100 times more potent than morphine – that has been linked to a recent surge in overdose deaths in Florida and across North America. Some people choose to purchase and use fentanyl, however, it is often covertly mixed with heroin batches unbeknownst to the buyer.

In the first half of 2016, there were 704 fentanyl-related deaths in Florida.

Under HB 477, anyone found in possession of between four and 14 grams of fentanyl will receive a mandatory minimum sentence (MMS) of at least three years in prison, and must pay a $50,000 fine. Possessing between 14 and 28 grams will result in an MMS of 15 years imprisonment, and a $100,000 fine. Someone possessing more than 28 grams will receive an MMS of 25 years, and a fine of $500,000.

The provisions of HB 477 do not differentiate between pure fentanyl and mixtures containing fentanyl. Thus, someone found in possession of four grams of heroin which contain a minuscule amount of fentanyl will face a three-year mandatory sentence.

As a point of reference, under Florida law, aggravated assault with a firearm carries a three-year mandatory sentence.

The legislation also introduces draconian new sentencing rules for people who sell drugs. If illegally-purchased fentanyl, or certain other opioids, are “proven to be the proximate cause of the death of the user”, the seller will now be charged with first-degree murder. The mandatory sentence for first-degree murder in Florida is either life without parole, or capital punishment – by lethal injection or the electric chair.

Greg Newburn, Florida state policy director for Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM), says that mandatory minimum sentences for drug offences are not a new concept in his state, and that the approach has demonstrably failed to achieve its goals in the past.

“There are more drug arrests, drug prison admissions, and overdose deaths in Florida today than there were in 1999 when Florida re-established harsh mandatory minimums for low-level drug trafficking offenses,” Newburn told TalkingDrugs, referring to the 1999 introduction of MMS to Florida statutes, which included prison terms ranging from three to 25 years for drug offences.

“This is an unambiguously bad strategy, and Florida taxpayers will be on the hook for its costly unintended consequences for years to come.”

Newburn’s message was echoed by the Drug Policy Alliance’s Tony Papa, who has experienced the severity of mandatory drug sentencing first-hand, and now campaigns for the reform of US drug laws.

Papa, who received a 15 years to life sentence for a first-time non-violent drug offence, told TalkingDrugs that MMS “is a poison that has destroyed our criminal justice system … contributed significantly to breaking the banks of states by filling its gulags with non-violent drug users.”

“The use of MMS will do nothing to reduce the fentanyl crisis because you cannot lock your way out of the problem of drug use or addiction,” he warned. “Instead of Governor Rick Scott adopting a get tough approach, a smarter approach should be made that will invest public resources into and treatment options”.

Indeed, there is a range of harm reduction measures that would be effective for countering Florida’s fentanyl crisis, including forensic drug testing to ascertain if a heroin batch contains fentanyl, the creation of supervised injection facilities (also known as drug consumption rooms), and wider supply of the overdose-reversal drug naloxone. HB 477 includes a provision that permits emergency responders to possess and administer opioid antagonists, such as naloxone, but this is unlikely to be efficient at reaching many communities.

Until Florida’s legislators adopt a compassionate health-oriented approach to the use of fentanyl and other opioids, it seems unlikely that the overdose crisis will end any time soon.