The upcoming midterm elections seem particularly heated and consequential, a referendum on President Trump – this is nothing new.

By Justin Martin / 09.18.2018

Author and Historian

The upcoming midterm elections seem particularly heated and consequential, a referendum on President Trump and his agenda on issues such as immigration, gun control, national security, and women’s reproductive rights.

This is nothing new. Throughout American history, midterms have provided an opportunity to place a check on a sitting president. Bill Clinton got hammered in 1994; way back in 1826 John Quincy Adams’s party lost both houses of Congress; Grover Cleveland, grappling in 1894 with a railroad strike and severe economic depression, saw his Democrats lose a record 116 House seats.

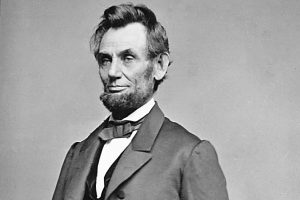

It’s no surprise then that Abraham Lincoln, mired in a civil war, faced the very real possibility of a drubbing in the 1862 midterms. “The bottom is out of the tub. What shall I do?” he famously lamented.

Robert E. Lee sensed Lincoln’s vulnerability. To the coolly calculating Rebel general, the Union president’s waning political fortunes spelled opportunity. Upon embarking on the South’s first-ever invasion of the North in September of 1862, he wrote to Jefferson Davis: “The present seems to be the most propitious time, since the commencement of the war, for the Confederate army to enter Maryland.”

Lee had a number of things in mind. He perceived that bringing the fight to Northern territory would demoralize the Union. Military success might prompt the European powers to extend diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy. As a careful reader of the Yankee press, with a good feel for Northern sentiment, Lee was also very much thinking about the “coming elections” as he put it in another letter to Jeff Davis.

It’s no accident that Lee launched his invasion in September. The midterm elections were only weeks away. He correctly perceived that Rebel victories on Northern soil might sow discord in the Union, sweeping the out-party Democrats into power in Congress, hobbling Lincoln’s presidency.

The North’s political landscape was by this time in a state of worrisome flux. At the war’s outset, Stephen Douglas, a Democrat and Lincoln’s great rival, had asserted: “There can be but two parties, the party of patriots and the party of traitors.” Democrats, eager to be on the honorable side, initially went along with Lincoln’s Republicans, supporting the war with little reservation. But Douglas had since died. The fragile sense of agreement between opposing parties in Congress was fraying mightily. (Remember, in this era, the parties were flipped ideologically; the Republicans were liberal, Democrats conservative.)

Throughout the spring and summer of 1862, the Union had suffered a series of crushing defeats. They had been driven from the Virginia Peninsula, Stonewall Jackson had rampaged through the Shenandoah Valley, and there was the debacle at Second Bull Run. The Democrats—the minority in both houses of Congress—were increasingly questioning Lincoln’s war effort, pointing to the escalating costs in lives lost and money spent. (The Federal Treasury was expending $2 million per day on the fight.)

A new faction of Democrats had even emerged, known as the Copperheads. These were deeply conservative Democrats, who urged an immediate cessation to the war on terms sympathetic to the South. They were even willing to invite the Confederate states back into the Union, slavery intact. Together, Democrats of all stripes, Copperheads and otherwise, had crafted what appeared to be a simple but devastating message for their fall campaigns: “The war is a failure.”

Every indicator pointed to a disastrous midterm. A New York Times article assessed the Union citizenry’s mood in 1862, describing them as “depressed by the reverses of the war” and “ready for the moment to seek a remedy in any quarter.” The sentiment was echoed by a female voter in Illinois, Lincoln’s home state no less: “people are becoming impatient and disposed to blame someone very greatly.”

However, despite it being a “propitious time,” matters did not turn out as Lee had planned. On September 17, 1862, the Battle of Antietam was fought in Western Maryland near the little town of Sharpsburg. It resulted in 3,650 deaths, still the highest toll of any single day in American history. After the muskets and cannons fell silent, Lee and his army retreated back across the Potomac River into Virginia. His Northern invasion had ended. The Union had managed a sorely needed win.

Not long afterwards—with the glow of the Antietam victory still fresh—the Union states held their midterm elections. Lincoln’s Republicans took a beating. The party lost 22 seats in the House as well as the governorships of New York and New Jersey. Republican majorities evaporated in the state legislatures of Illinois and Indiana. The results left the president and his White House “blue” according to one of Lincoln’s secretaries.

Yet it could have been so much worse. Despite losing those 22 seats, the Republican Party still retained control of the House. This broke a pattern, going back twenty years to 1842, in which the opposition party always managed to seize the House during midterms. What’s more, Republicans gained five seats in the Senate, giving them a robust two-thirds representation in that branch. Victory at Antietam was a key to insuring that an overall poor performance by Lincoln’s Republican party didn’t devolve into utter disaster.

On November 7, 1862—the midterms safely behind him—Lincoln sacked George McClellan, commander of the Union’s Army of the Potomac. Lincoln and his general had a notoriously strained and combative relationship. As it happened, McClellan was a Democrat and a popular one, in a high-profile position to boot. Meaning: it would have been more difficult to remove him had Congress been of a different political complexion. Firing McClellan began a process—with some setbacks along the way— in which Lincoln ultimately chose as his army commander Ulysses Grant, a man the president was better disposed toward temperamentally, a general capable of winning the war.

Indeed, following midterms that left Republican congressional majorities intact, Lincoln sensed that he had a mandate. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which made freeing the slaves an explicit war aim. It fired up the Federal army, invested the soldiers with a new and nobler purpose. The Emancipation Proclamation proved critical—arguably, the key—to the Union’s ultimate victory in the Civil War.

Yes, as we’re frequently reminded these days, presidential elections have consequences. So do midterms.

Originally published by History News Network, reprinted with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.