Photo by Juan Antonio Segal, Flickr, Creative Commons

Bolsonaro’s win served as a wakeup call to Portugal, where the far-right is on the rise.

By Margarida Teixeira / 11.27.2018

The international press followed the Brazilian elections closely when it became clear that Jair Bolsonaro, the far-right candidate, had a good chance at winning. In one of the most significant countries for the Brazilian diaspora, due to the historic and cultural relations dating from colonial times, it created divisions among political groups and it was seen a clear warning sign that no country is immune from the far-right.

Over 80,000 Brazilians live in Portugal, by far the largest immigrant group in the country. Last month, 64,4% of Brazilians living in Lisbon and 65,5% of Brazilians living in Porto (the two largest cities of the country) voted for Bolsonaro, who managed to win in those cities by a much higher margin than in Brazil itself.

The results shocked left-leaning Brazilians and Portuguese alike, and it was a stark contrast with the results of the Paris and Berlin Brazilian diaspora, which leaned towards the left candidate Fernando Haddad.

Danger at the polls

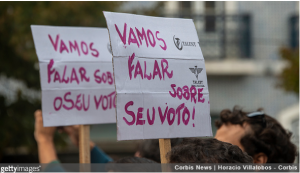

On both election days (first and second round) there were concerns about the safety of voters, a rare occurrence in Portugal, where the biggest challenge is getting people to vote rather than restraining voters’ fanaticism.

A video of a Bolsonaro supporter presenting himself as a “white, italian, heterossexual” fascist in front of the voting station of the Lisbon Faculty of Law during the first-round of elections, as other voters called for police presence and screamed at each other, represented the tension.

Many left-leaning Brazilians denounced the hypocrisy of Brazilians living in Portugal (that has a socialist government) voting for Bolsonaro, saying that with their vote they were stripping Brazilians living in Brazil of rights they took for granted in Europe (such as publicly funded healthcare or education). Others argued that the decision to immigrate to Portugal could be explained as an escape to the problems Bolsonaro saying he would fix (economic crisis, corruption and violence) and that many immigrants were hostile to the Brazilian political establishment.

Brazil and Portugal mirroring eachother

While many Portuguese were stunned by the polarization of Brazilian elections and most of the intellectual elite positioned itself against Bolsonaro, it was not uncommon to step into a café or a bus and hear people excusing Bolsonaro’s violent words against minorities or women and compliment him for his urge to fight against corruption and insecurity in Brazil. The comments on news articles criticizing Bolsonaro were also particularly virulent, often depicting the candidate as the victim of an international smear campaign.

These reactions were at odds with much of mainstream media. For weeks, journalists and intellectuals in Portugal campaigned against Bolsonaro. There were videos, open letters and op-eds written against him. A group of female MPs from left-wing parties of the Portuguese parliament took a picture with the symbols of the #EleNão (Not Him) campaign and many political figures supported protests in Portugal against the candidate.

It’s hard to recall any other foreign election that incited so much political engagement against a candidate, specially from elected officials.

Divided local politicians

These displays of repugnance towards Bolsonaro, however, emboldened the right to accuse the left of disrespecting the feelings of ordinary Brazilians. Even though some prominent right wing commentators denounced Bolsonaro as a fascist and publicly stated they would have voted for the left candidate, others shrugged off both options as equally despicable.

That indifference to the social justice issues (such as sexism and racism) that were crucial for Bolsonaro’s opposition was clear in the statements of current and former right wing leaders. The (female) leader of CDS-PP, a Christian right-wing party, stated she would abstain, if given those two choices. Other two prominent right-wing politicians, Santana Lopes and Paulo Portas, were equally neutral on the issue, claiming there was nothing unethical about Bolsonaro or that he might actually strengthen Brazilian democracy.

While Bolsonaro’s victory seemed to make the left suddenly in favor of expelling immigrants, (an elected official of the Lisbon Municipality wrote on Facebook that Bolsonaro voters residing in Brazil should “return to their country and enjoy their freedom there”), it also made the far-right an admirer of Brazilians.

Populism and fake news spreading from Brazil to Portugal

The, only and quite small, official far-right party in Portugal, PNR, routinely demonizing Brazilian immigration, was quite happy with the outcome of elections and celebrated Brazilians’ choices, apparently ignoring the fact that many Brazilians might now choose to immigrate to Portugal at even higher rates than before.

The insecurity, the fanaticism and the casual indifference towards fascism of the Brazilian elections left a mark in Portugal, a country that has been largely immune to far-right populism, and served as a test-run for what a far-right candidate might expect in order to win over Portuguese voters.

Unlike the French, Italian or American elections, Bolsonaro’s propaganda was in Portuguese, so people had access to it directly. Also many Portuguese people had friends online and offline that argued for Bolsonaro, giving Portuguese direct access to the debate.

Pro-Bolsonaro propaganda mostly took the form of links disseminated via Whatsapp and many “Portuguese” websites participated in spreading fake news. A series of articles about fake news websites, usually based in foreign countries but dedicated to Portugal, show how quickly a fake image or statement can circulate in the Portuguese web.

Lessons for the future

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was in the midst of the Brazilian elections that a right-wing populist decided to launch a new political party, in order to supposedly to fight corruption, forbid gay marriage (it’s already been legalized in Portugal), chemically castrate paedophiles and implement life sentences for criminals. His new party has about two thousand likes on Facebook and although it was featured in basically all mainstream news outlets, no major figure has supported it.

There have not been any far-right parties present in the Portuguese parliament since the end of the dictatorship in 1974, so our political history hopefully indicates this new party is doomed to failure. But the Brazilian elections taught Portugal to remain vigilant, serving as a wakeup call.

Originally published by Wikipedia under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.