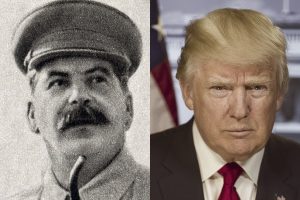

Trump is not the monster Stalin was, but the evil he has already unleashed and his potential for causing greater future evil should not be underestimated.

By Dr. Walter G. Moss / 10.28.2018

Professer Emeritus of History

Eastern Michigan University

After attending six President Trump rallies in October 2018, the New Yorker’s Susan Glasser wrote, “The biggest difference between Trump and any other American President, however, is not the bragging. It’s the cult of personality he has built around himself and which he insists upon at his rallies.” She added that he calls to the stage other Republican politicians who flatter him with lines like “Is he not the best President we have ever had?” and he is “the strongest President we have seen in our lifetime.”

The term “cult of personality” became prominent in the twentieth century in 1956 when Nikita Khrushchev delivered a mind-boggling Secret Speech, “On The Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,” to the 20th Party Congress of the USSR’s Communist Party. In it he spoke at great length of the harm Stalin had done to the Soviet Union by fostering such a cult around himself: “The cult of the individual acquired such monstrous size chiefly because Stalin himself, using all conceivable methods, supported the glorification of his own person.” Khrushchev also criticized Stalin for branding some of his political opponents as “enemies of the people,” and claimed “Stalin originated the concept enemy of the people. This term automatically rendered it unnecessary that the ideological errors of a man or men engaged in a controversy be proven.” (Long before Stalin, however, the Norwegian dramatist Ibsen used the term, entitling one of his plays “An Enemy of the People.”)

Trump has also used the phrase, as David Remnik (editor of the New Yorker and a former Washington Post correspondent in Moscow) noted in his “Trump and the Enemies of the People” (August 15, 2018). The editor quoted Khrushchev’s memoirs, recalling that Stalin referred to “everyone who didn’t agree with him as an ‘enemy of the people.’ ” Trump, however, has used it specifically to refer to what he calls “Fake News.”

Attempting to create a “cult of personality” around himself and labeling portions of the media—but not all of it, not Fox News for example—as enemies of the people does not make Trump another Stalin. Calling our president Stalinesque or Hitlerite just feeds into the overheated rhetoric of our times, which has become too common.

So why compare Trump to Stalin? Merely to point out some similarities—but also differences—by comparing and contrasting the two men, and thus enlightening us further about our current president.

Let’s start with the similarities. To begin with, there are the two giant egos, which are the bedrocks of the personality cults. One of the best biographers of Stalin writes that “his Messianic egotism [was] boundless.” Trump’s egotism is also limitless as indicated by such statements as “I’m very smart. My life has proven that I’m smart”; “I get along with everybody . . . . Everybody loves me”; and “My whole life is about winning. I always win.” Glasser’s New Yorker piece declares that at his this year’s early October rallies he claims “he is the hero of every story. All ideas, big or small, flow through him now that he is President.” In a recent snit about the Federal Reserve raising interest rates, which could hurt Republican mid-term chances, he declared “I think I know about it better than they do.” (What a contrast to more humble presidents like Washington and Lincoln!)

Second, both men think of those who would challenge their inflated views of themselves as enemies. Stalin had the power to kill many of them; Trump does not and simply makes statements like this one: “I would never kill them, but I do hate them. . . . Some of them are such lying, disgusting people.” (Michigan campaign rally, December, 2015.)

Third, both men are extremely suspicious and power-hungry and therefore intolerant of any opposition, however slight it might be.

Fourth, both men have relied on fear to increase and solidify support. Railing about enemies all around, domestic and foreign, has been one method both men have used. Remnick quotes Khrushchev’s memoirs as stating, “Everyone lived in fear in those [late 1930s] days. Everyone expected that at any moment there would be a knock on the door in the middle of the night and that knock on the door would prove fatal.” In his 1956 Secret speech, Khrushchev said “mass arrests and deportations of many thousands of people, execution without trial and without normal investigation created conditions of insecurity, fear and even desperation.” The writer Isaac Babel remarked in the midst of Stalin’s terror campaign in the 1930s, “Today a man talks frankly only with his wife—at night, with the blanket pulled over his head.”

About Trump, James M. May, author of How to Win an Argument: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Persuasion (Princeton, 2016) wrote shortly before the 2016 election:

Mr. Trump has cleverly and successfully identified a collection of emotionally-charged issues—from the ever-increasing national debt to illegal immigration to the threat of domestic terrorism—that have some significant resonance with a large portion of the electorate. He plays upon fears that certainly have legitimacy for many people (e.g., the loss of jobs or the threat of a terrorist attack), and he offers hope that these fears and anxieties can be allayed with a change in leadership (“Make America Great Again!”). The crowds that he has attracted and the enthusiastic, sometimes almost frenzied reactions that he evokes, testify eloquently to the power of emotionally-based persuasion.

An example of what May was referring to were candidate Trump’s comments about our immigration system, which he thinks too lax. According to him, it allows in too many terrorists, rapists, killers, and people from “shithole countries” like Haiti and African nations.

Since becoming president, he has continued his fear mongering. In August 2018, he told Fox News “If I ever got impeached, I think the [stock] market would crash. I think everybody would be very poor.” During the Kavanagh hearings, amidst sexual allegations against the judge, Trump declared, “It’s a very scary time for young men in America when you can be guilty of something that you may not be guilty of.”In October, he told a campaign rally in Iowa, “The Democrats have become too extreme. And they’ve become, frankly, too dangerous to govern. They’ve gone wacko.”

Fifth, both men are colossal liars. Stalin constantly made false charges and oversaw the falsification of history about him and Russia generally. By the end of July 2018, the Washington Post concluded that “President Trump has made 4229 false or misleading claims in 558 days;” or as CNN summarized it an average of “7.6 mistruths a day.”

Sixth, after becoming the dominant political leader in their countries both men began the process of solidifying their control over their party and the government bureaucracy. Because of different political cultures (more on this below), the institutions involved were quite different. But Stalin had much greater control over the Communist Party and the Soviet government by 1935 than he did in 1928. As for Trump, his dominance over the Republican Party is certainly greater today than at the time of his election. Regarding the government, he and his supporters have complained of a “deep state,” by which they mean “a cabal of unelected leftist officials lodged deep in the government who are conspiring to thwart the administration’s policies, discredit its supporters and ultimately even overturn Trump’s election.” But Trump has made strong efforts to remove “disloyal” bureaucrats from such agencies as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Michael Lewis, author of The Fifth Risk, has estimated that “of the top 6,000 career civil servants in the federal work force, 20 percent of them quit or were fired the first year of the Trump administration.”

Undoubtedly, more comparisons could be made, but the contrasts are just as important. The most significant is that the two leaders have operated in two very different political cultures, one dictatorial and the other democratic. Russian tsars and then Lenin laid the groundwork for Stalin, though his evils surpassed those of his predecessors. President Trump is much more limited in the harm he can do. Congress and the courts, for example, have so far prevented some of his most egregious acts from being carried out in regard to immigrants, wall-building, and health care, though he has still been partly successful. Moreover, his appointment of two Supreme Court justices and a multitude of new lower-court federal judges reflect an increase in his judicial influence. Since coming into office, he has benefitted from Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, but with mid-term elections coming up that could change.

The results of those elections will highlight just how different our own political culture is from that of Stalin’s Soviet Russia. We, the people, have the power to crimp severely, and even impeach, our leader. Soviet citizens had no such authority. If Republicans increase their majorities in the November elections, it is we citizens who are handing Trump more power.

As unlikely as that appears at present, such a ceding of political might is not unprecedented. A good example is Hitler’s coming to power in 1933. Despite its weak democratic traditions, Hitler became chancellor by constitutional means in January 1933. It was only after the Enabling Act of March 1933, by which the German legislature granted him legislative power and allowed him to suspend the constitution, that Germany ceased the democratic experiment of the Weimar Republic. In our own country, one leading Democrat, Adam Schiff, has recently charged that “the Republican Congress has not only failed to assert itself and review or investigate the conduct of the executive; worse, it has also been complicit in some of the president’s most egregious attacks on our democratic institutions.”

Yet one powerful force curtailing Trump’s authoritarian ways that neither Stalin nor Hitler had to contend with is strong media opposition. Despite the popularity of Fox News and Fox personalities like Sean Hannity, the majority of major newspapers (like the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times) are critical of Trump, as are many other media outlets in television (including late-night hosts), on Public Radio (federal funding for which Trump wishes to end), and on the Internet.

Another major difference between Stalin and Trump—one that Trump supporters would justifiably point out—is that Stalin was responsible for the deaths of millions of his own citizens, and no one is accusing Trump of such bloodshed. (His rhetoric, however, could lead to future blood-spilling.)

Still one more obvious difference, somewhat related to the above, is that Stalin dominated the Soviet Union for about a quarter of a century, and Trump has only been our president for a little less than two years. After two years as the supreme leader in the USSR, Stalin had not yet become as powerful as he would be by the late 1930s. If Trump remains in office for four years (or perhaps even eight), who knows how much harm he could do? The long-term effects of his presidency will not be known for many years. The most catastrophic effect, affecting the lives of millions, could be his refusal to take climate change seriously.

In summary, the egotism of Stalin and Trump has led both men to cultivate personality cults around themselves and to label their opponents as enemies or “enemies of the people,” but heretofore Trumpian evil is minor compared to that caused by Stalin. But this difference stems partly from the more democratic political culture of the United States and partly from the relatively short time Trump has been in office. He is not the monster Stalin was, but the evil he has already unleashed and his potential for causing greater future evil should not be underestimated.

Originally published by History News Network, reprinted with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.