Addressing low levels of civic engagement often means recognizing citizens as advocates for their neighborhoods.

By Chayenne Polimédio, Elena Souris, and Dr. Hollie Russon-Gilman / 11.15.2018

Polimédio: Deputy Director

Souris: Research/Program Assistant

Russon-Gilman: Fellow

Political Reform Program

New America

Executive Summary

Americans by large margins say that government does not work for them. Studies show that the views of average people are not well represented and people don’t believe they are heard by those in power. This crisis of representation often leads to a crisis in participation. Solutions to the low levels of engagement and lack of faith in democracy, its institutions, and its representatives tend to lack sustainability and scalability. Proposed solutions often favor technocratic expertise over experience. Apps and new data sets become the way to just fix problems in the short term; metrics and measurable wins take precedence over collaborative policymaking and genuine constituent empowerment that would lead to sustainable improvements in the quality of life for all.

Fresh thinking about civic engagement does not have to be complex. The best approaches go back to the basics, ask the right questions, and focus on the people. Well-designed partnerships among the public, private, and nonprofit sectors, along with philanthropic and public investment in physical spaces, informed by the lessons of human-centered design can help tackle the crisis of representation and participation facing many American communities.

In Philadelphia, the fifth-largest city in the United States and one long strained by racial and class tensions, new thinking about civic engagement, trust, and participation has taken the form of a massive investment of philanthropic and public resources into the city’s neglected public spaces and civic infrastructure, including recreation centers and libraries. Can these investments, if designed to draw in residents and engage them in local decisions, help rebuild the bonds of community and democratic trust? This is a question relevant to cities and towns all across the country. Philadelphia’s experience may provide some answers.

Governments, along with the philanthropic, private, and nonprofit sectors, have begun to support such work. Foundations are increasingly aware that while the growth of urban economies has generated great wealth, it has also widened inequality. Funders are responding by supporting policies and models of engagement that seek to ensure that residents are able to benefit more equitably from economic development.[1] In addition, the private sector has begun to think about distressed cities and localities as opportunities for development. And government officials have welcomed the capital and the expertise that oftentimes understaffed and cash-strapped agencies lack.

In Philadelphia, democratic need, funder support, fresh thinking, and municipal and resident commitment to change come together. At the invitation of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, we explored two of its investments. The nonprofit Fairmount Park Conservancy is leading a civic engagement effort in advance of Rebuild, an initiative led by Mayor Jim Kenney that will invest hundreds of millions of dollars to improve neighborhood parks, libraries, and recreation centers. The second one is the PHL Participatory Design Lab, a 2017 “Knight Cities Challenge” winner, which uses behavioral economics and human-centered service design to improve public services provided by the Office of Homelessness Services and Department of Revenue.

Our goal was to develop some insight into what kinds of interventions are likely to have the most impact in promoting sustainable civic engagement and more inclusive, equitable, and responsive public policy. First, we looked at the link between investments in physical infrastructure and civic engagement. Second, we studied inclusive design practices that aimed to take users’ experiences into account when designing policy and government communications. We tested assumptions in these two models of individual engagement, and we looked at how these models can apply in other cities.

Our research took us to one of the first disc golf courses in the world, to city hall, and to neighborhoods across Philadelphia.

Our investigative framework tested several assumptions:

- That investments in physical capital can yield higher levels of social, human, and economic capital.

- That community and group involvement lead to residents who are more engaged in their neighborhoods and local governments

- That individuals want to engage in governance and to take part in community-oriented activities.

- That individuals will get involved if the costs and barriers to engagement are lowered.

- That barriers to engagement can be lowered with the creation of better tools and processes.

- That civic technology is a tool for positive change and an asset to civil society organizations and other forms of social entrepreneurship.

This paper is a combination of desk research, dozens of in-depth semi-structured interviews, and multiple site visits and follow-ups. Through a snowball sampling approach, where we started with an initial group and expanded it in a systematic way while learning about community networks, we were able to identify key actors and institutional players, as well as engage with community members.

Much of the work that we examine in this paper—from applying user-centered research to improve government services to investing in renovations in physical spaces in order to develop social capital—reflect twenty-first century realities and challenges that must be grappled with by those in charge of policymaking, those who advocate for such interventions, and the people for whom policies are crafted.

We found that addressing low levels of civic engagement often means recognizing citizens as advocates for their neighborhoods, and that hearing the public’s expertise requires investing in civic structures, listening to new voices, and taking chances on new ideas. By combining experience with technical knowledge and building with citizens rather than for them, solutions that focus on social capital investments go beyond the voting booth and carry potential for sustainability and scalability.

Based on our research examining civic engagement in Philadelphia, as well as our broader assessment of the literature and the civic engagement landscape, we have compiled findings and recommendations geared to a wide group of stakeholders. This includes public officials, civil society, community members, philanthropy, the private sector, and academia. These high-level findings and recommendations help contextualize our experience on the ground in Philadelphia within the broader civic innovation ecosystem. The recommendations section of the report goes into deeper detail.

Findings

- There is no “one-size-fits-all” model for civic engagement. Different models will work better and be more inclusive depending on who participates, how they engage, and what types of opportunities are available, as we saw with Philadelphia’s range of programming.

- Process and implementation can slow down progress. City officials and policy makers can easily miscalculate how long it will take to pass a bill like the soda tax, or get funding for a program like Rebuild. These delays may discourage under-resourced residents from participating, while well-resourced residents familiar with the political process can wait it out.

- Civic organizations, such as the Philadelphia nonprofit Fairmount Park Conservancy, can complement municipal government and help offset its limitations.

- Though technology and digital tools provide more civic engagement opportunities, technology alone does not effectively eliminate barriers to entry or help attract more diverse viewpoints. When integrated as part of a policy process , as with the Design Lab, technology has a lot of power.

- Ideal resident input systems communicate to users what happened as a result of their contributions. Positive feedback loops help residents experience success either individually on a campaign or as a sense of shared effort with others, which can help build their sense of agency. One example may be the volunteer groups in Philadelphia: advisory councils at recreation centers and the friends groups at parks.

- Local governments and engagement structures should encourage proactive and positive engagement, rather than incentivizing residents to merely participate in response to a problem. For example, the Philadelphia Parks Alliance does grassroots-style outreach around rec centers’ neighborhoods to match renovations with the communities’ specific needs.

- Improving civic engagement must include reforms that make democracy more equitable. While programs such as Rebuild, the Design Lab, and volunteer groups have an impact, it’s important to think about what other structural factors may impact traditional democratic processes.

Long-Term Recommendations

- As the soda tax case teaches, it’s helpful if funders can adopt an if-then model to plan for unforeseen events, delayed political timelines, or limited funding streams to keep projects and grantees moving.

- Plan for “sailboats, not trains” by thinking about civic engagement funding as a long-term, adaptive investment without rigid planning or short horizons. Such a framework would help projects adapt to obstacles like the Rebuild project has faced.

- Design sustainable funding streams by encouraging public spending and public/private partnerships where philanthropic money acts as a “down payment” on expected public investment. To do so, funders can support increased municipal capacity by backing fellowships or helping departments find innovative, yet self-sustaining, funding sources.

- As powerful as programs like Rebuild can be, the political arena also deserves attention. Promote structural reform and discussions about the role of money in politics, voting reforms (like ranked choice voting), and the resources that government needs in order to do its job.

Medium- to Short-Term Recommendations

- Build a civic layer to create a spectrum of engagement for individuals that meets them where they are in the evolution of their “civic life,” providing different levels of engagement and accessible opportunities. As Philadelphia departments and nonprofits implement different outreach methods, other organizations can experiment with tactics ranging from block-walking outreach to roles that work directly with the City.

- Invest in training for government employees and civil society leaders, similar to city volunteer trainings, as well as more diverse employment outreach.

- Avoid one-off, occasional engagement by developing an ongoing and iterative system for residents through outreach, input, and participation. Philadelphia friends groups and resident advisory councils are an instructive model.

- Bring engagement into the 21st century by taking advantage of modern technology and asking whether these tools are engaging all residents. For example, volunteer groups talked about both the benefits and limitations of social media.

Introduction

Across the globe, studies show alarmingly low levels of trust in government institutions.[2] In the United States, low levels of trust have most commonly manifested in voters’ lack of interest in politics, low feelings of efficacy, and low participation in elections.

But getting people to vote, while a crucial right, does not need to be the only way to foster feelings of political efficacy. While elections are usually perceived as the primary mode of citizen engagement with government, in the medium-range future, collaborative policy models can be a critical component of how people engage. Municipal and local leaders have an opportunity to integrate ways for residents to engage that go beyond the voting booth.

As urbanist Jane Jacobs argued in the 1960s, cities foster genuine public and civic spaces, because they “have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”[3] Cities, where people play in the same parks and take the same public transit, can act as a testing ground for people to try to find solutions together, especially against the backdrop of our increasingly polarized national politics. Several cities are gaining nationwide attention because of their bold and inclusive approaches to incorporating civic engagement into people’s daily lives on a sustainable basis. Part of the excitement of studying civic engagement in Philadelphia is its place within the broader conversation occurring in the U.S. around the notions of “progressive federalism,”[4] American renewal, and the concept of communities as “laboratories of democracy.”

Why Philadelphia?

An aerial view of Dilworth Park in downtown Philadelphia. / Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department

Philadelphia is what professor and urban studies theorist Richard Florida calls a “Patchwork Metropolis,” where the city and the wider metropolis have an inner more privileged “creative class” with a working-class outer rim. The result is one of the highest levels of inequality in the county, with 26 percent of the population living below the poverty line. Philadelphia is also one of only five American cities to be classified as “hyper segregated” between 1970 and 2010, according to Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey. The result is that a majority of the city’s black residents live in areas that are isolated from most white residents.[5] In Philadelphia, as in Baltimore and Chicago, there is a 20-year gap in life expectancy between parts of the city’s poor, largely black neighborhoods, and its wealthier, whiter areas. This disparity can be seen in neighborhoods as close as five miles apart.

But Philadelphia also boasts a civic infrastructure with many entry points for experimentation.[6] The city has one of the largest and oldest park systems in the U.S., with more than 100 parks encompassing 10,000 acres. In addition, Philadelphia has a large network of recreation centers that complement these historic parks, and a well-established library system.

These public spaces offer meeting places for residents to interact and forge new connections. Community anchor institutions such as parks and recreation centers can strengthen the fabric of civic, social, and political life. However, these spaces must be accessible, clean, safe, and equitable, which is not always the case. Deterioration in Philadelphia is severe, and public engagement is low.

Citizens enjoy a Philadelphia park in the 1800s. / Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department

But fresh thinking about civic engagement does not require dramatic solutions. The best approaches often go back to the basics, ask the right questions, and focus on people and communities. Bringing together residents and government employees to work on solutions to city problems together is a simple way to bridge lived experience and technical expertise. Another approach is making the idea of civic engagement more concrete by helping connect people and their relationships to one another, and their city to physical spaces. For this model to work, there ought to be solid human and physical infrastructures in place.

The Common Thread: Where Lived and Technical Experiences Meet

In Philadelphia, new thinking about civic engagement, trust, and participation has taken the form of a massive investment of philanthropic and public resources into the city’s neglected public spaces and civic infrastructure, including rec centers and parks. Can these investments, if designed to draw in residents and engage them in local decisions, help rebuild the bonds of community and democratic trust? This is a question relevant to cities and towns all across the country. Philadelphia’s experience may provide some answers.

All of the case studies in this paper share one common thread: they look at addressing low levels of civic engagement through recognizing citizens as advocates for their neighborhoods. They recognize that doing so requires investing in civic structures, listening to new voices, and taking chances on new ideas. By combining lived experience with technical knowledge and building with citizens rather than for them, the solutions that focus on social capital investments—be that via investments in physical capital or human-centered design methods—go beyond the voting booth and carry potential for sustainability and scalability. While all the case studies in this paper were of projects currently underway in a specific setting (Philadelphia), we believe that the “expertise meets experience” model can be applied across the board.

This paper explores two investments in the Knight Foundation’s civic engagement portfolio in Philadelphia. The first of these is the civic engagement process led by the Fairmount Park Conservancy, as part of Rebuilding Community Infrastructure (Rebuild)—an initiative led by Mayor Jim Kenney that will invest hundreds of millions of dollars to improve neighborhood parks, libraries, and recreation centers.[7] The second one is the PHL (Philadelphia) Participatory Design Lab, a 2017 “Knight Cities Challenge” winner, which combines behavioral economics and human-centered service design to inform policymaking enhance the public’s trust in government.

Part of the methodology used for this paper included the assessment of frameworks (see the appendix for full list) about how, why, and when people engage. These frameworks served as guidelines for determining what works and what does not when it comes to new models of civic engagement, and how models can be better tailored to serve residents.

Our theory of change is visualized below: the goals of any practitioner—city official, activist, or organizer—are to simultaneously engage more residents in civic spaces in their neighborhoods and also improve city programs and services based on residents’ needs.

Click image to enlarge

Each case study below has its its own set of particular circumstances that have led to successes and potential obstacles. A common thread lies in the way multiple stakeholders (foundations, city officials, and community members) are coming together and looking for bold, innovative ways to harness lived and technical experience in ways that could be replicated beyond Philadelphia.

Innovative city government and civic engagement must include a municipal framework of multi-party, vertical, and horizontal partnerships that empower different stakeholders, residents, and experts. Philadelphia provides multiple examples of overlapping partners, as well as showcasing the variety of ways in which city employees, policy experts, nonprofits, and researchers can work together to address local problems. These examples speak to the different ways that cities and residents can rethink both their partnership and empowerment potential, and the outcomes that they can produce as a result.

Instead of residents only having incentives to participate in response to a problem, local governments and engagement structures can promote proactive and positive engagement. This requires city officials to recognize residents as experts on their own neighborhoods, and it also means that residents need access to trainings on organizing, community engagement, financial compliance, leadership and conflict resolution, and the municipal structure.

What follows are two case studies. The first explores the relationship between physical spaces and civic life using Rebuild’s experience with the Philadelphia Parks & Recreation system (in partnership with the Fairmount Park Conservancy), which brings together city staff, nonprofits, and multiple levels of resident involvement to maintain sites across the city. The second studies how Philadelphia has incorporated human-centered approaches both in its policy design and in its outreach models to improve interactions between residents and the city, through the work of Design Lab.

To better understand the different stakeholders and organizations involved in these case studies and projects, please refer to this table:

Click image to enlarge

Case Study 1: Physical Spaces as Civic Spaces

A Knight-supported Assembly Civic Engagement Study, which came out in 2017, assessed “the ways in which neighborhood design is connected to civic attitudes and behavior.”[14] In looking at the connection between individuals’ feelings of efficacy and belonging when in public spaces, the study addressed four areas that test the relationship between civic space and engagement.

- Civic trust and appreciation: Do individuals feel they are a part of a collective identity? Do they appreciate the value of public spaces and feel invited to participate? Do individuals recognize local government and other responsible parties that provide and maintain collective civic assets?

- Participation in public life: Do public spaces provide the opportunity for contact and socialization with neighborhoods and strangers which facilitates equitable access and positive interactions among diverse groups?

- Stewardship of the public realm: Do individuals feel responsible for public spaces and express that in a practical way, by advocating for improvements and additional funding and by participating in maintenance, programming, and beautification?

- Informed local voting: Do those who are eligible to vote feel informed about their choices, are registered, and cast a ballot in local elections? Do individuals express their civic engagement in local politics by contacting officials, signaling support for issues, or exhibiting knowledge about the role of local government?

One of the important aspects of civic and communal life, especially in dense cities, is the role of social relationships or “social capital.” University of Chicago sociologist James S. Coleman—one of the earliest thinkers about the role of social capital in promoting healthy societies—argued that “unlike other forms of capital, social capital inheres in the structure of relations between actors and among actors. It is not lodged either in the actors themselves or in physical implements of production.” Coleman added that “social capital…comes about through changes in the relations among persons that facilitate action,” and “just as physical capital and human capital facilitate productive activity, social capital does as well.”[15]

One aspect of social capital is that people establish relationships with intent and then continue to develop these relationships, which provide benefits. But beyond relationships, structures are also key in fostering and sustaining social capital. Those include, for example, the family, the school, the church, and social organizations that give the individuals who participate in them meaning and purpose. This is an aspect of social capital which is inextricably linked to public spaces and public goods.

Edward L. Glaeser, David Laibson, and Bruce Sacerdote, in writing about economic approaches to social capital, have argued that “while we have theory and evidence on the effects of social capital, we are just beginning to identify the underlying mechanisms that create social capital in the first place.”[16] Because of that, further data, research, and analysis are especially important as social capital is declining—a phenomenon pointed out by many observers of American society, such as Harvard professor Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone.[17] Rebuild is a good opportunity to begin to study and understand the interplay between physical spaces and social capital.

Rebuild was conceived of three years ago. David Gould, deputy director for Community Engagement and Communications, says that the question that inspired the project was, “if we could borrow money to invest into the system, what would it look like and how would we go about it?” Rebuild’s goal was to determine where those investments would be made, who they would serve, and what goals they would seek to accomplish, by prioritizing high-need neighborhoods to promote equity. The project has also sought to select sites where investment could help to stabilize or revitalize a community.[18] The William Penn Foundation—a Philadelphia-based foundation—pledged $100 million to neighborhoods for Rebuild.[19] The Knight Foundation is supporting Rebuild’s public-private partnership model through investments throughout the city.

Rebuild’s goals are hefty. Over the next few years, its three-pronged approach will seek to 1) Revitalize parks, recreation centers, playgrounds, and libraries; 2) Empower and engage with communities; and 3) Promote Economic Opportunity for all Philadelphians. Goals 1 and 2 were the main focus of our study when looking at the work that the Fairmount Conservancy is seeking to do.[20]

The project’s funding model—a seven-year, $500 million investment—involves city government capital funds ($48 million); state, federal, and philanthropic grants ($152 million); and Rebuild bonds. These bonds were issued by the Philadelphia Authority for Industrial Development and will be funded through revenue from the Philadelphia Beverage Tax, which taxes sweetened drinks at 1.5 cents per ounce. The “Philly Bev Tax” or “soda tax,” as it has become known, was approved in 2016. The soda tax was challenged by a lawsuit from the American Beverage Association, but in July 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in favor of the soda tax, which helps secure the funding for Rebuild and its future projects.[21] The plan is for the bonds to be issued in three tranches of $100 million. Philadelphia is the first major U.S. city to pass a soda tax.[22]

The project was informed by neighborhoods that displayed high need (using indicators such as poverty, drug crimes, health indexes) and that could benefit from stabilization and revitalization (through market value analysis, household growth, and residential building permits).[23] Having all of that data available to the public promoted transparency and helped decision-makers avoid any questions about which sites were chosen for investment.

Deciding which sites will get Rebuild investments has been a challenge, however, since even a $500 million investment will not be enough to meet the needs of Philadelphia’s entire parks and rec system. Thus, it becomes a matter of priorities. So far, the city council has approved 64 sites. Vare and Olney Recreation Centers are expected to be the first to start work, as well as Parkside Fields, Glavin Playground, and Heitzman Recreation Center.[24] The first step will be processing and approving project user applications, and then holding community engagement meetings in the winter. Smaller projects, like fixing broken sidewalks, should begin sooner.

A Rebuild community meeting, hosted at the Disston Recreation Center on April 24, 2018. / Photo by Elena Souris

Once sites are chosen, Rebuild’s civic engagement process gives residents the opportunity to “provide input and a seat at the table,” Gould told us. Rebuild will also look for ways to invest in the people that make the parks, rec centers, and libraries the valuable resource that they are despite their condition. That will mean implementing capacity-building programs for city staff (including librarians and rec leaders), and investing in community members who have dedicated time and energy to those spaces.

With their compatible institutional structures and organization, governments and nonprofits are natural partners that can come together to help build up a consistent structure for citywide progress. Because they can play different roles and operate within separate spheres, public-private partnerships can complement and supplement one another.

For Rebuild’s Deputy Director for Community Engagement and Communications, David Gould, that includes making “sure that improvements are reflective of the community’s priorities and needs.” In practice, that involves using the physical improvements process as a gateway to civic engagement and the beginning of civic trust. The communities Rebuild was designed for, Gould told us, are “marginalized and under-resourced communities that are distrustful of government, and have had bad experiences with government.” Rebuild gives people an opportunity to have a positive experience with government, which could potentially leave them more inclined to participate in their communities in the future. Rebuild’s civic engagement component aims to be customized to the communities that the spaces will serve. The process of engagement, Gould believes, is as important as the physical space renovations themselves.

Through participating in discussions focused on “what kinds of improvements their parks and rec centers need,” Gould told us, Philadelphia residents have an opportunity to have a real hand in improving those spaces. This, in turn, can heighten their feelings of personal efficacy. But engagement incentives need to be structured in a sustainable way that extend beyond moments of crisis or political challenges.

Rebuild has its limitations when it comes to engagement. Meetings are announced via email and social media and are held in the evenings during the week, normally around 6 p.m. While meetings are moved around to different rec centers throughout the city so as not to prioritize one neighborhood over another, this approach can make it difficult for some residents to participate consistently, if at all.

Ambitious projects like Rebuild can have a tangible impact on changing the civic engagement landscape of American cities. But with big goals come the challenge of implementation. Over the next few years, Rebuild’s three-pronged approach will continue to face the capacity and authority challenges that it is facing now. Philadelphia Business Journal/WHYY reporter Malcolm Burnley pointed to how Mayor Kenney’s words, when he announced the first rec center that would be receiving Rebuild funding, “reflected the strain of a budget season riddled with conflict over Rebuild’s union diversity goals, his proposed property tax increase and spiking home assessments that will further hike tax bills in many parts of the city.”[25]

Because of its size, slower-than-predicted execution, and large number of actors involved, Rebuild has moved at a slower pace than initially planned, frustrating some of the residents it aims to include. Part of the challenge has been getting city council to approve the sites proposed in a timely manner. Another issue has been ensuring a revenue stream that will fund all of these investments, as the soda tax was delayed for months by legal challenges.

The Role of Civic Intermediaries: The Fairmount Park Conservancy

In late 2017, the Knight Foundation awarded $3.28 million in new funding to the Fairmount Park Conservancy to support a citywide civic engagement strategy that will allow residents to shape activities in Philadelphia’s public spaces. One part of the Conservancy’s work is to implement some citywide engagement processes in advance of Rebuild, to ensure that investments tied to Rebuild are reflective of residents’ needs.

In implementing Rebuild, civic intermediaries and existing environment infrastructure play a critical support role in the civic engagement strategy, programming for residents, and public space resources. The Conservancy is one of these intermediaries, a nonprofit that supports Philadelphia’s city-owned and operated parks, playgrounds, and programs. According to its mission statement, the Conservancy works in a collaborative fashion to assist a variety of organizations and to “lead capital projects and historic preservation efforts, foster neighborhood park stewardship, attract and leverage investments, and develop innovative programs throughout the 10,200 acres that include Fairmount Park and more than 200 neighborhood parks around the city.”[26]

The Knight grant helps the Conservancy support a network of public and nonprofit partners—including Philadelphia Parks & Recreation, Philadelphia Parks Alliance, and Free Library of Philadelphia—so it is better equipped to play its part in Rebuild. These groups help Rebuild foster community participation around public spaces, mobilizing residents as co-creators in shaping their neighborhoods.[27] The Conservancy and its partners’ initial work included a scan of the current environment of volunteer groups across the city, in order to determine which parks have established groups, which do not, and the current capacities of those groups. These groups represent over 200 volunteer organizations integral to engagement and programming in public spaces—whether parks, rec centers, or libraries—that the Rebuild initiative will invest in.

In addition to acting as gatekeepers of engagement for residents in these public spaces, these volunteer groups also have long-term stewardship over public assets, a role that will be important before, during, and after Rebuild implementation. As a result, the Conservancy’s work has involved conversations with these groups to identify their current capacity and to learn about community needs. As Jamie Gauthier, the Conservancy’s executive director, told us, “the goal is to make them stronger, have better governance structures, financial controls, learn to fundraise, and to develop programming. Our work will seek to help them make the best possible use of the public spaces that Rebuild is about to invest in.” To further these efforts, the Conservancy also offers some small grants to these grassroots organizations, as well as learning opportunities, workshops, and trips. Future opportunities may include small pilot interventions or pop-ups to give community groups ideas for permanent improvements.

Within the Rebuild process, the Conservancy has been designated a “project user.” As a project user, the Conservancy is one of 21 neighborhood-based and city-wide organizations that are approved to work on Rebuild projects and can bid on individual sites. Project users will manage site contracts and progress on construction and diversity goals.[28] At the same time, project users will work with other community groups to foster civic engagement around each library, park, or rec center. This includes supporting community outreach, interaction, and engagement to guide and inform the capital project development. While the Conservancy will be limited to the specific sites it is approved for in the Rebuild context, its community engagement work includes city-wide efforts to continue investing in the greater volunteer group network, which is something the organization has done for the past six years.

It is important to “make stewardship fun and engaging, not only by connecting stewards with resources and a larger network but by celebrating and recognizing them,” Jennifer Mahar, senior director of civic initiatives at the Conservancy, told us. “These groups,” she said, “represent the diversity of the City” and therefore efforts to strengthen them must “build authentic, two-way relationships with these individuals and their communities.”

The work that the Conservancy does as a civic intermediary is crucial to the overall civic engagement ecosystem in Philadelphia. The Conservancy bridges the public and government in ways that help them work together and takes on a role that residents may be unequipped for or the government legally may not. According to sociologist Xavier de Souza Briggs, civic intermediaries can bring together multi-stakeholder actors and “compensate for a lack of civic capacity because of what government, business, or civil society organizations are not able, or not trusted to do, and also—along a more temporal dimension—for process breakdowns, such as impasse, polarization, and avoidance, that thwart collective problem solving.”[29] In this way, intermediaries like the Conservancy can work as complementary partners for the City and other nonprofits to support their work in the long and short terms, offer funds, and facilitate active and inclusive participation.

Bringing the City and Residents Together Around Parks & Rec

The Disston Recreation Center exterior. / Photo by Elena Souris

Philadelphia is a city built around its parks, starting with William Penn’s original 1682 city design that featured five parks as main elements of a grid system.[30] While the Parks and Recreation departments were originally separate, the two merged in 2008. The now joint Philadelphia Parks & Recreation (PPR) department oversees 9 historic and cultural sites, 157 recreation centers, 157 parks, and 74 swimming pools.[31]

The Philadelphia Parks & Rec system features many different stakeholders: the Philadelphia Parks Alliance (PPA), the Fairmount Park Conservancy, the Commission on Parks & Recreation, and the Philadelphia Recreation Advisory Council (PRAC). PPR manages the entire system and its municipal budget, which is set by the mayor and approved by the city council.

Two generations ago, the City of Philadelphia estimated that it was seeing the beginning of a population increase that would peak in the 1970s, level out in the 1980s, and hold steady until 2000. The City made infrastructure investments, including in the parks and rec system, to anticipate this projection. Those numbers never came. Instead of growing, the City’s population decreased between 1960 and 2000, as more people moved into the suburbs. As the population decreased, so did tax revenue, so the City had new municipal infrastructure without the expected funds to maintain it properly.

A neighborhood park closed for maintenance. / Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department

Even though the population started increasing again between 2006–2014, that growth came at a much lower rate than the city originally expected, never reaching the estimated peak. PPR Chief of Staff Tiffany Thurman explains that over the same period, the operating season has also increased; because the weather is warmer for longer than previously, the parks must be operable and maintained for more time out of the year than before. The parks and rec system is now facing more demand, without the matching tax revenue that the City assumed would accompany it. As a result, PPR has had neither the operational budget to hire necessary maintenance staff nor the capital budget to fix infrastructure. Today, these sites are often dilapidated after decades of what Thurman calls “deferred maintenance.”

Impacts of deferred maintenance and a lack of funding at the Vare Recreation Center. / Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department

This “deferred maintenance” has impacted these public spaces in various ways. Some parks have broken sidewalks that affect walkability. When playgrounds or safety matting fall into disrepair and out of compliance, the City must take the chains off the swings and hang up “DANGER” signs. Some rec centers have leaking roofs, broken boilers, or lack air conditioning systems. As is often the case in city government, PPR must prioritize and make difficult decisions. While Thurman explains that there are resources to provide items like tables and chairs to the rec centers, big issues sometimes do not get fixed because there simply is not enough money.

To understand why an investment as large as Rebuild is necessary, it’s important to convey the scope of the problem. These are photos of a limited sample of damaged parks, rec centers, and playgrounds to show the need in some neighborhoods, as well as before and after pictures to showcase the transformational power that such investments can bring to a community. The Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department kindly granted their permission for us to use these photos in this paper.

Impacts of deferred maintenance and a lack of funding at the Cecil B. Moore Recreation Center. / Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department

However, this is not to say that all public sites in Philadelphia are at this level of disrepair; these photos only show two sites, Cecil B. Moore and Vare recreation centers. Each community has their own unique needs, and our scope of research didn’t include visiting each site or each of the 64 Rebuild sites.

When the city has the capacity, however, they can turn rundown sites into beautiful and welcoming community spaces.

Hunting Park before renovations from the Hunting Park Revitalization Project. / Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department

The brand new neighborhood playground after the Hunting Park Revitalization Project investment. / Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department

Resident Volunteer Groups: The Pros and Cons of the Model

The Rebuild program will help address the biggest challenges and act as an emergency fund transfusion for the deferred maintenance problems. But on a normal, day-to-day basis, local resident volunteers play a crucial role in helping the sites function by working on smaller projects, light maintenance, and programming. Bringing in volunteer community members as neighborhood activists and experts through advisory councils (ACs) and friends groups (FGs) is one way that Philadelphia is addressing the structural budget challenges and capacity problems outlined above.

At recreation centers, ACs partner with the Philadelphia Parks Alliance; Philadelphia Parks & Recreation; and Philadelphia Recreation Advisory Council to raise money for resources, give input on programming, perform light cleaning and maintenance, organize special events, and promote the center within the neighborhood.[32]

Recently, PPR created a liaison position for a city employee—the civic engagement manager—to work with ACs and rec leaders and facilitate that relationship. Previously, this responsibility bounced around between different officials without having full-time support. The civic engagement manager’s role in overseeing over 90 advisory councils is to help make both the residents and the rec centers better and stronger in the future, though that is a long-term goal that could take several years.

Part of the PPR’s new attention on ACs has involved looking for ways to strengthen civic infrastructure through Rebuild. To do so, PPR Chief of Staff Tiffany Thurman says that the department is making sure they are investing in the neighborhood, not just the facility; establishing programming that fits community needs; and “being intentional about the relationship between rec leaders and the neighborhoods they serve.” As PPA Executive Director George Matysik explains, the vision is to think outside of standard rec programming like basketball, and to adapt, grow, and stay relevant in the community over time.

For the parks system, FGs work closely with the city, the Conservancy, and their own neighbors. These groups oversee fundraising for investment projects, manage and offer programming, and regularly take care of small maintenance issues, like weeding or trash pick-up.[33]

The FG program volunteer group format allows for a range of personalization for different neighborhoods. Eileen Gargano, resident of the Friends of Dickinson Square Park, plans movie nights, children’s workshops for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, and workdays where volunteers pull weeds and do light maintenance. John “Stash” DiSciascio, executive director of the Friends of Sedgley Woods, a disc golf course in Fairmount Park, organizes a Family and Friends Day; social gatherings for members; and tournaments to raise money for their disc golf course, other friends groups, and various charities. Gargano says that she feels that the city recognizes these groups’ position as dedicated volunteers and local experts, and Antonio Hunter, PRAC VP says that the relationship feels like a respected give and take. Hunter told us that he and the PRAC board can collaborate with the city to solve problems, but that there is still responsibility and autonomy given to the groups. For DiSciascio, this model works well because “the best caretakers are the stakeholders.”

Members of the Sedgley Woods Friends Group. From left to right: Derrick “Turtle” Eason, President John “Stash” DiSciascio, Jason Bates, Michael “Chicken” Cacciatore, and Benjamin Wendell. / Photo by Elena Souris

Including residents in governing through models like the volunteer group is effective, but this model still has its challenges. We heard three themes in our research and interviews in our small sample of volunteers and senior officials in the City, Conservancy, and PPA. They may reflect broader structural limitations and lend insight for other localities looking to build a community-based civic infrastructure to support public spaces. These include complicated internal and external relationships, unrealistic pressure on volunteers, and potentially exclusive engagement.

First, there can be ambiguity in maintaining clear relationships, boundaries, and divisions of responsibility between groups. For example, the division of tasks between ACs and rec leaders became somewhat complicated for the period that PRAC was not as actively managed and those roles were not clearly defined. Because there is a natural overlap between those two positions, the formal system has built in a range of checks and balances. The ACs manage the funds for the rec center. But, while two AC members must sign off on any checks, the rec leader physically holds those checks and keeps them at the center. The rec leader also provides and reports on monthly financial statements. However, because both the rec leader and AC members share power and responsibility in the rec centers, there is the potential for personality clashes or misunderstandings based on viewing the arrangement as a hierarchy rather than a collaboration.

In well-established groups and councils, especially, there may also be a disconnect between volunteers who have been part of the group for a decade or more and residents who reflect recent neighborhood demographic changes. One of the biggest challenges for FGs and ACs is getting to a consensus and mediating between contrasting neighborhood priorities.

Second, while a friends system gives residents active management roles and provides civic opportunities, it also puts pressure on them to deliver results. As tends to be the case with any kind of sustained civic engagement, only a certain subset of the population tends to participate. Actively participating in FGs and ACs at a sustained, consistent level—not to mention running them—can favor those who have the extra time, expertise, financial connections, and political and municipal familiarity. Gargano, Hunter, and DiSciascio noted that their positions all started with getting involved with the community on a smaller scale first; in other words, they were self-selected as engaged volunteers, rather than a product of recruitment or outreach. DiSciascio said that his duties as executive director of the Sedgley Woods friends group usually take around 5–10 hours a week. Gargano said that the amount of time her role as president of Dickinson Square friends group takes will vary by season but can range from 5 hours to 40. As a retiree, this time demand is feasible for her, but she sometimes wants a break, too, joking that she occasionally “prays for snow.”

In times of constrained budgets, the model of devolving roles and responsibilities to volunteers demonstrates both the opportunity provided to residents as well as the consequences of responsibility. For example, while the city hires maintenance staff, they are seasonal employees with limited hours. For parks, many FGs are expected to fill this gap themselves with weekly or monthly clean-up days. At rec centers, this can mean that ACs have to coordinate and fund buying new program materials.

The engagement opportunities provided to residents also assume that FGs and ACs will provide a level of maintenance and quality oversight that’s unrealistic to expect for volunteers’ time and other commitments. Perhaps this contributes to the original problem of minimal maintenance compounding into absent or overwhelmed maintenance, building into disrepair. After time, these sites then require major investments like Rebuild. This also means that after such investments, volunteers are responsible for maintaining the improved sites, even if they may not have the capacity to adequately manage the buildings as they currently stand.

As one example, the model of fee-based classes as a method of generating revenue for the rec center does not work for every AC. While some ACs are in neighborhoods where residents can pay for aftercare programming or summer camps, others cannot. One impact of the restricted parks and rec budget is that small capital investments or maintenance are sometimes funded by the friends groups, in addition to other agency sources. Most FGs and ACs have treasury positions for this purpose. This requires understanding the necessary legal, and at times complex, bureaucratic logistics and requirements for fundraising.

Third, there can be limits on inclusion within the volunteer groups. Within neighborhoods that have changed over time, this model can reflect and amplify only a subset of the community’s concerns and interests. That is because the financial capabilities of volunteer groups can also vary based on factors like the socioeconomics of a neighborhood or a group’s skill in fundraising and available time to take advantage of the city’s trainings.

While the system is trying to ensure inclusive, equitable civic engagement, these skill sets can be barriers to entry. One obstacle stemmed from the legal challenges to the soda tax, which, though now resolved, led to delays. Given the nuances surrounding the process itself, and the legal formalities surrounding financial compliance, volunteers can find it challenging to navigate both city government bureaucracy and nonprofit management.

The PPR is working towards more balanced support for the volunteer groups. While Philadelphia’s goal is to have a volunteer group for each park and rec center, Thurman says city hall is aware that pushing for group development too quickly can create a system that does not reflect the community well, or one that will quickly die out. To ensure inclusion, PPR provides trainings for groups that cover a range of topics, from financial regulations to leadership and conflict management. The Conservancy is groups’ go-to for finding extra support and help applying for grants.

Especially in view of the Rebuild process and the new infrastructure it will bring, both the Conservancy and PPA are working to build up the volunteer groups’ long-term capacity. The Conservancy is helping with scans of the individual groups, acting as a resource, and helping guide thinking around civic engagement. PPA is starting neighborhood outreach around rec centers that do not have established ACs to help bring in new volunteers and start new discussions around what the community wants. While Rebuild marks a concrete, financial investment in infrastructure, the PPR, Conservancy, and PPA are doing parallel work to simultaneously invest in the volunteer infrastructure that will be just as crucial.

The system has potential. Currently, though, it runs a risk of being viewed as transactional in what it expects from resident volunteers, and potentially too dependent on their help.

Making Civic Engagement About Community Engagement

In 1960, political scientist E. E. Schattschneider famously observed that “the flaw in the pluralist heaven is that the heavenly chorus sings with an upper-class accent.”[34] Inclusive models of civic engagement take into account who does or does not participate, how they do or do not engage, and the type of engagement. In America, economic inequalities tend to mirror political inequalities, so those who with higher levels of education, more time and resources, and greater feelings of efficacy may be more likely to participate.

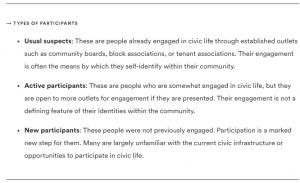

One way to think about who participates is to think about how individuals identify in their communities. Do people think of themselves as those who always are engaged (usual suspects); as those for whom civic life is a small component of life (active participants); or as those who have previously not been civically engaged (new participants)?[35]

Click image to enlarge

Going beyond the usual suspects also entails using language that is equitable and inclusive. For example, the term “citizen,” which is often used in the context of civic engagement, tends to leave out everyone else without that particular identity. Especially when communities are distrustful of government—when there is heightened political tension, for example—language is more important than ever. Civic engagement needs to be viewed as a safe space in which people can work together, meet new people, and improve their communities. FGs and ACs, for example, act as channels for civic participation and government interaction. They allow residents, including those without legal status, to play a role in advocating for their community.

Another example is the Philadelphia Parks Alliance. While the name implies a focus on parks, today the PPA mostly works on Philadelphia’s 150 rec centers in response to their outsized need. For Executive Director George Matysik, PPA’s two main goals are to re-imagine what rec centers can do for their communities and to act as a support network for ACs. As he puts it, “libraries are more than just books, and rec centers are more than just basketballs.” Instead, he wants to see rec centers respond to more general community needs by boosting advisory councils and helping guide programming.

Before starting investment into a recreation center, PPA hosts community dinners to discuss how it can best serve the neighborhood’s needs. Matysik or members of his staff begin outreach by going door to door, starting across the street from the rec center and working outward. When residents open their doors, the PPA team lets them know about the upcoming event, which often leads to a conversation about the rec center, the current challenges it faces, and what the community would like to see. With this model, several organizations, including PPA, the Conservancy, and Philadelphia Free Library, meet the community where it is, rather than expecting all interested parties to be able to come to them. Community members who cannot attend the meeting have a chance to voice their opinions when PPA staff members knock on their door. Matysik mentions often running into kids playing outside and soliciting their input, whether or not they can attend the meeting with an adult later—though he says many of them do.

During the community dinners—where free pizza is provided, and turnout varies from 30–40 to as many as 200 people—Matysik starts by asking what the community needs, rather than what the rec center needs. He has found that by asking the first question, he gets answers like “ESL classes” or “job training programs.” Asking only about what the rec center needs yields answers usually limited to sports equipment, or what people think rec centers are “supposed” to have. From there, the PPA sets up more community meetings and later holds elections for advisory council positions, creating an effective outreach pipeline for community members to build up sustained engagement with their rec center and put their ideas into practice. With or without a Rebuild investment in a rec center site, the general goal is to “have the community inform the built environment, not the other way around,” he says.

In assisting with the building of advisory council capacity, the PPA helps recruit volunteers and strengthen existing councils’ institutional structure. Today, there are approximately 550 AC volunteer members who are, in effect, running mini nonprofit boards for their rec centers. Their tasks involve raising money, overseeing programming, and advocating for their center with the city.

In addition to helping build up the ACs’ structure, the PPA also helps them implement the ideas that came up during the dinners. If community members ask for a specific program, the PPA helps them get started by assisting with grant writing or even providing some seed money. Part of building up AC structure is investing in long-term sustainability, especially because Rebuild is a short-term project. This effort also helps ensure that neighborhood wealth disparities do not also translate into AC disparities.

Case Study 2: City Hall as a Site for Innovation

Solutions to municipal problems can be hybrid models of expertise: while residents are able to point out problems and difficulties in specific neighborhoods because that is where they live and those are challenges they must deal with daily, city employees know the legal and bureaucratic process and often have a big picture view of city dynamics.

The City of Philadelphia is a pioneer of sorts when it comes to government departments using open data to help bridge the gap between policy design and its intended outcomes. In city hall, human-centered design is one tool in a broader innovation toolkit which includes behavioral insights, civic engagement, open data, and evidence-based decision-making. This is all part of a strategy to enhance how city government operates and how it interacts with residents to create better policy.

The entrance of the Philadelphia Municipal Building in downtown Philadelphia. / Photo by Elena Souris

Since 2011 with the launch of OpenDataPhilly,36 which has been dubbed the “country’s first community open data catalog,” Philadelphia has been part of an early wave of urban innovation, along with city governments in Washington D.C., San Francisco, and London in their efforts to make open data collection and sharing an essential part of public knowledge and open government.[37]

In 2012, Philadelphia was one of the first cities, after Boston, to launch a Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics, an innovation hub to test models of technology and civic engagement.[38] Philadelphia was one of the winners of the 2012–2013 Mayors Challenge and received a $1 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies to implement FastFWD to help entrepreneurs solve big public challenges while also reforming the procurement system. That same year, then-Mayor Michael Nutter signed an executive order making open data the government default.

Open data and digital technology helped spur innovation within city hall. External funding from philanthropy in particular has helped catalyze support for how data and digital technologies can benefit public policy. For example, the William Penn Foundation is one of the early supporters of open data, and the Knight Foundation has supported the redevelopment of the open data catalog in Philadelphia.[39]

The mayor’s policy office, in collaboration with local academics, developed the Philadelphia Behavioral Science Initiative to create low-cost interventions that effectively nudge behaviors that have a positive impact on both residents and government. Key questions include identifying how to increase recycling efforts and reduce litter; increase voter turnout; and nudge city employees to participate in a wellness program, among others.

In February 2017, Mayor Kenney’s administration formally launched GovLabPHL, a multi-agency team led by his policy office focused on further embedding evidence-based and data-driven practices into city programs and services through cross-sector collaboration. The GovLabPHL team partners with city agencies to identify how evidence-based methods can intersect to address common municipal challenges to enhance policymaking, programs, and services. GovLabPHL is focused on the application of behavioral economics, human-centered design, and a trauma-informed approach.

The mayor’s policy office, through GovLabPHL, partnered with the Office of Open Data and Digital Transformation (ODDT) to host a 10-month speaker series in 2017 (funded by former grant dollars from the nonprofit Living Cities and support from the University of the Arts Design for Social Impact Program[40]) on the role human-centered design can play in improving city service delivery, and again partnered in 2018 to host a city form redesign event.

To date, GovLabPHL is managing 12 pilot projects in partnership with city agencies and academics. ODDT collaborates with city departments to publish open data.[41] To make those data available, ODDT is taking what Data Services Manager Kistine Carolan calls a “maximally useful” approach: recognizing that research can both identify resident needs and inform how to shape data in the most useful way.

According to ODDT, the series convened diverse stakeholders with the goal of cultivating a cross-sector conversation on how design strategy methods were used to “improve affordable housing application processes, to explore connections between opiate use and jail overcrowding, to increase access to services for veterans and their advocates, to reorient government around the needs of its constituents, to craft more accessible government information systems, and to challenge the cycle of poverty by designing holistic, empowering cross-sector financial services.”[42]

The case studies that were presented at the speaker series exemplified not only the successful adoption and continued use of strategic design, but also its sustainability across levels of government. From there, a community of practice—comprised of policymakers, design professionals, academics, community members, public servants, and advocates—was built. Awareness of the use of service design has increased for both city employees and public sector leadership.

This human-centered design approach seeks to find the balance between resident experience and technocratic expertise. Through building in partnership with users, policymakers aim to understand what public sector strategic design looks like in practice, and what role it can play in transforming government services for the better. It looks for learning opportunities between the public and private sectors, and how the former can learn inventiveness from the latter. But, most importantly, in designing around the needs and experiences of users, policymakers must grapple with how complex government agencies can avoid adding additional burden to its employees, and still be able to deliver more dignified, accessible, and equitable services.

Anjali Chainani, director of policy in the mayor’s office, sums up the value of this work: “we’ve learned that the consequences of not approaching the city’s work through a behavioral economics lens is a risk to getting our best return on investment. If we can better connect policy improvements to on-the-ground service delivery processes and tools, then we can be more effective in holistically enhancing the public’s experiences with city services.”[43]

Bridging Experience and Expertise: The PHL Participatory Design Lab

Since it started its Cities Challenge in 2015, the Knight Foundation has looked directly to communities to ask them how to make their cities better.[44] The 2017 Knight Cities Challenge asked, “what’s your best idea to make cities more successful?”[45] Building off the momentum of leveraging data, technology, and innovation within city hall, the PHL Participatory Design Lab became a 2017 Knight Cities Challenge Winner from a national pool of 4,500 applicants.[46] Philadelphia, which received the most funding, was approved for five projects: Up Up & Away: Building a Programming Space for Comics & Beyond; A Dream Deferred: PHL Redlining—Past, Present, Future; Vendor Village in the Park: Vending to Vibrancy; Tabadul: (Re)Presenting and (Ex)Changing Our America; and the Design Lab, which is studied in this paper.

In Philadelphia, participatory design methods have led to cross-agency and cross-sector collaboration that, in turn, has improved government services. The Design Lab is the City of Philadelphia’s effort to improve its service delivery to residents using social science and service design methods. Human-centered design is a design and management process for engaging the users in product design. Instead of the top-down approach to developing and deploying products, human-centered design involves a multi-step process to assess users’ needs, incorporate feedback, and make changes accordingly.[47]

The Design Lab deployed fellows for two current pilots with city hall to help community members and city departments work collaboratively.[48] One pilot seeks to improve the intake experience of people interacting with the Office of Homeless Services. The other is a policy experiment with the Department of Revenue’s Owner-Occupied Payment Agreement, which assists homeowners behind on their real estate taxes. The Design Lab is led by Liana Dragoman, service design practice lead and deputy director of the ODDT, and Anjali Chainani, director of policy in the Mayor’s Office of Policy, Legislation, and Intergovernmental Affairs and is comprised of a multi-agency and -disciplinary team of service designers, social scientists, and policymakers.

The Design Lab is a team of six City of Philadelphia employees using research and data to improve how the city interacts with its residents. The team also hires fellows to deploy for specific projects. As its full name suggests, the work done by the Design Lab aims to be participatory. It has worked with city departments, organizations, and residents to improve services.

With the 2017 Knight Cities Challenge award, the team had 12 months to redesign aspects of city services. City agencies applied to do specific pilots with the Design Lab, which ensured that they were energized to apply the social science and service design tools of the Design Lab within their agencies.

The Design Lab has worked with OHS and the Department of Revenue to improve residents’ experiences with those city services, specifically as a way to address the housing crisis in Philadelphia, which is amongst one of the most challenging in the country.[49] Other departments participate and share learning through initiatives like the speakers’ series.

In thinking about how to communicate this work, Dragoman described that they are focused on “trying to make it look collaborative, friendly, and welcoming and looking for ways to communicate in plain language, so partners and observers fully understand the work and don’t confuse it as being solely a technology or traditional visual design project.”

Design Lab Pilot with Office of Homeless Services

Philadelphia’s Office of Homeless Service (OHS) offers emergency housing facilities, transitional housing programs, permanent supportive housing, and finance assistance to prevent homelessness.[50] With OHS, the Lab’s goal has been to “employ service design methods to improve the experiences of the public when interacting with the OHS centralized intake system.”[51] The Design Lab conducted interviews with personnel across different parts of the system, including intake staff, and with participants who are accessing or refusing to use intake services in order to identify opportunities for process improvement. OHS includes emergency housing facilities, transitional housing programs, permanent supportive housing, and finance assistance to prevent homelessness.[52]

OHS welcomed the opportunity to take a systematic look at how people are experiencing the intake process. Each year, OHS intake sees 20,000 people, diverting 40 percent from emergency housing.[53] Part of the project’s goal is to collaborate with OHS staff, leadership, and participants to define what person-centered service delivery looks like in practice. Devika Menon, the Lab’s service design fellow, looks at experiences from beginning to end and learns from them in order to, she said, “design improvements with those who use, advocate for, and deliver services.”

To do this, the Design Lab team works with both internal and external stakeholders. This includes conducting interviews with people experiencing homelessness at the different intake sites and shadowing and interviewing front-line staff in an effort to better understand how, why, and whether people choose to access emergency housing services. The team also worked to identify pain points both for participants and city staff and to craft strategic and realistic recommendations with city staff and leaders.

OHS staffers noted how thoughtful and sensitive the service design team was in conducting interviews with participants as well as in providing detailed updates. As one OHS staffer described working with the Design Lab, “it’s been a truly collaborative experience from the beginning. They have respect for the team and the people they interact with; they really respect and interact with the people we serve; they understand how vulnerable people feel at those points.”

One of the lab’s findings in its interviews with users of homeless services was the demoralizing effect of not being able to bring individuals’ own food into the intake centers. Because of health and sanitation concerns, the intake centers had families discard their food before entering. OHS is now working to make changes to this system.

Menon was drawn to this project because she felt there was a lot of enthusiasm and that OHS was really welcoming and “open to the design process.” She told us that her approach is that “we, as designers, aren’t coming in to ‘fix a problem.’ We recognize that people are experts in their own lived experience. I see our role as facilitators of the design process to make improvements that aim to make the participant experience better and staff’s job easier.”

The project with OHS demonstrates a few critical components of the Design Lab approach. First, because agencies volunteer to work directly with the Design Lab, they show a commitment to try new approaches. OHS recognized that it is working with a limited supply of resources and is open, willing, and excited to try a new approach. This is important to ensure that the recommendations from the Design Lab can become fully implemented into agency execution.

Second, the internal process between OHS staff and the Design Lab service design team puts a premium on transparency and, in turn, fosters collaboration and trust. This internal process includes weekly updates and being sensitive about the limited capacity of the agency. A co-creative process helps ensure that the ultimate recommendations that the Design Lab creates with OHS will be realistic and meet the goals and objectives of OHS.

Finally, by engaging with front-line staff and residents, the Design Lab demonstrates a commitment to including people in a service redesign process, showing that change can be driven from community members themselves.

Design Lab Pilot with Department of Revenue

The Department of Revenue’s experiments with behavioral science and human-centric design began in 2012, when it applied for a City Accelerator grant from the nonprofit Living Cities to work on poverty. The goal of the project was to have more people enroll in taxpayer assistance programs. According to former Director of Taxpayer Assistance and Credit Programs Graham O’Neill, this program works with some of the most vulnerable citizens in Philadelphia who are navigating high poverty, literacy challenges, and a large digital divide. With that grant, the department was able to do both formal behavioral science experiments around taxpayer outreach and help share those lessons with other city departments.

In working with the Department of Revenue, the Lab’s focus has been on using social science and service design methods to improve the public’s interactions and experiences with the Owner-Occupied Payment Agreement (OOPA). This program “assists homeowners behind on their Real Estate Taxes and provides protection from enforcement action.”

While the department already gets a lot of feedback—almost a billion calls, 150,000 in-person visits, and one-third of the city website’s traffic in one year, as well as a formal appeals process with the Tax Review Board—those responses do not always answer questions about what approaches are more effective. When they do, it is anecdotal.

By using behavioral science, under the leadership of social scientist fellow Nathaniel Olin, the Design Lab takes what we know about human nature and incorporates that into how policy is made in an attempt to make the user/resident experience more effective, meaningful, and inclusive.

And since the Department of Revenue is also well positioned to implement behavioral science experiments—outcomes are easily quantifiable based on the amount of taxes it collects and assistance it provides—working with the Design Lab was an obvious next step. For example, since the department is legally bound to send most communication through the mail, the Design Lab implemented a simple A/B testing model where different versions of the same message were sent out to randomly generated groups of addresses.

With their different designs, the department tested different tones, messaging, outreach methods, and graphic design to see what made the right impact. They found that a matter-of-fact tone worked best: people did not like a cheery tone, and while a scary tone worked, it made the resident-government relationship more difficult. Using the clearest language about the harshest possible penalties (loss aversion) was more effective than noting which park their tax dollars were benefiting (social norms messaging). Sending mailouts every 30 days saw better rates of payment than with the standard 60–90 days. To test outreach approaches, they tried a variety of different tactics: hand-addressed letters were extremely successful. Different sizes of envelopes, however, had no impact. As for graphic design, anything that looked too glossy or fancy did not go over well: people either thought it was spam or wasteful.

Based on this work, the Design Lab is also now providing behavioral science conferences for other city employees to help them produce better forms. In one event, the schedule includes a panel of speakers, including external experts, and the opportunity to workshop their own forms. The Design Lab has also organized what it calls “Formpalooza,” an event aimed at collecting public feedback about forms, albeit from a limited population sample. The second conference it held allowed participants to bring back results from experiments they tried to continue workshopping the process. Having a network of academics to pair up with city employees has also been crucial to ensure that information is randomized and data are tracked correctly.

Recommendations

Addressing low levels of civic engagement requires recognizing the public’s expertise as advocates for their neighborhoods and as individuals who know, firsthand, their communities’ most pressing needs. That means an openness to listen to traditionally marginalized voices and a willingness to experiment with new ideas. Foundations’ investments in civic infrastructure and human-centric design experiments in Philadelphia are examples of this kind of approach. Solutions that focus on social capital have the opportunity to engage communities beyond the voting booth, with the potential for sustainability and scalability.

Regardless of the many challenges yet to come, the civic engagement models we studied in Philadelphia could change the way advocates and policymakers think about what civic and community engagement looks like. The recommendations below are both short- and long-term ideas based on an eight-month long learning process about Philadelphia’s civic engagement ecosystem, philanthropic funding, and the likely future of these “expertise meets experience” initiatives.

Long-Term Recommendations

Adopt an If-Then Model

If the Philadelphia Rebuild case illustrates one lesson, it is the way that political timelines can slow down progress, and how city officials and policymakers can easily miscalculate them. After many months of political hurdles and objections to the soda tax after Rebuild was approved and announced in December 2017, the future is looking secure. As of July 2018, the Philadelphia Supreme Court ruled in favor of the soda tax, enabling the work of Rebuild to get underway.[54]

Over the last few months, the funding faced political hurdles, and maintaining momentum for Rebuild was a challenge. Multiple coordinators noted fatigue from volunteers in friends groups and advisory councils because of this delay. Other volunteers were more cynical, noting that they never expected the money to really make a difference for them or their groups.

Planning for unforeseen events throughout a project, like Rebuild and the projects funded through the Knight Cities Challenge can be challenging. Heidi Grant, a social psychologist who studies the science of motivation, proposes that organizations adopt what she calls an “if-then”model to how they approach hurdles and challenges. She writes: “If-then plans work because contingencies are built into our neurological wiring. Humans are very good at encoding information in “‘if x, then y’ terms and using those connections (often unconsciously) to guide their behavior.” This means that once individuals have a plan of action, they tend to be able to adhere to it and follow through. Grant adds, “when people decide exactly when, where, and how they will fulfill their goals, they create a link in their brains between a certain situation or cue (‘if or when x happens’) and the behavior that should follow (‘then I will do y’). In this way, they establish powerful triggers for action.”[55]

In the case of foundations’ philanthropic investments in Philadelphia, “if-then” planning can be a useful strategy to keep grantees motivated and funders prepared for political challenges, like delays to the soda tax legislation, getting council members to select sites for renovation, or even overcoming resistance to change from civil servants. But, as Grant points out, “creating goals that teams and organizations will actually accomplish isn’t just a matter of defining what needs doing; you also have to spell out the specifics of getting it done, because you can’t assume that everyone involved will know how to move from concept to delivery.”[56] Thus, by ensuring that alternative scenarios are built into grantmaking, funders can be better positioned to tackle setbacks, delays, and unforeseen changes as politics and contingencies unfold.

Plan for “Sailboats, Not Trains”