The Trump election integrity commission thrust voter registration records into the spotlight last week. Here are six “did you know?” tidbits about voting practices in the states.

By Kathy Gill / 07.04.2017

Technology Policy Analyst

The Trump election integrity commission thrust voter registration records into the spotlight last week. The gnashing of teeth that followed that request sparked this review of voter registration lists, vote by mail, what the U.S. constitution says about elections, same day voter registration, open primaries, and voter fraud/voter suppression. (Links jump to each subject.)

1. Basic voter registration information is a public record in most states.

Voter registration came about in the late 1800s, requiring county officials to keep voter registration rolls. Basic information — name, address, voting record, data of birth — is a public record (with strings attached) and may be free for the asking, so long as you say you aren’t “commercial.”

Basic voter registration information does NOT include the last four digits of your social security number. Or who you voted for (secret ballot). Or if you were a felon. Or had registered in another state. All things that the Kobach letter asked for, without justification.

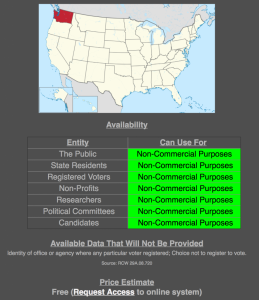

Here’s how Washington State treats requests for voter registration rolls, from the US Elections Project (2015 data):

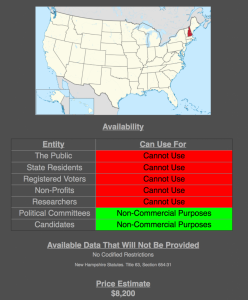

New Hampshire, on the other hand, is more restrictive than Washington. And not free.

State law is the reason that elections officials responded the way that they did to the letter from Kris Kobach last week: we’ll give you public info but nothing else.

Unless state law expressly prohibits sharing the data with another government agency, states will probably (IANAL) be legally required to hand over the data that they would share with any other requester.

Want to tighten the requirements for releasing voter registration data in your state? Lobby for change!

2. Some states vote by mail (think, permanent absentee).

Oregon was the first state to vote 100% by mail, followed by Washington. Colorado has joined the vote by mail family, but is in the last stages of the transition period (which is the most expensive). California will begin holding all-mail elections in 2018.

Arizona, California, Montana and Hawaii allow permanent absentee voting. This means that they run parallel voting systems: one by mail, one at the polls. Duplicative. Expensive.

Vote by mail is more convenient for most citizens (the ballot comes to you weeks in advance and you don’t have to stand on line to cast a ballot). It eliminates the need for extensive early voting polling locations, although there remains a need for some accessible voting centers. It eliminates the security risk of transporting and storing computers at the polls. It centralizes ballot processing, reducing the number of people needed and insuring all are trained and paid (no volunteers).

Here’s another reason, not cited often, for vote by mail: intimidation at the polls.

There was a lot of noise last year about efforts to “watch” the polls. Every American has the right to vote free of intimidation and discrimination. Everyone.

Eliminate polls, eliminate the opportunity for intimidation. And yes, there were rumblings in Washington last year about “watching” ballot drop box locations but they didn’t materialize. I’m thinking strategically-placed GoPro cameras to nix that mischief.

Read Dangers of “Ballot Security” Operations: Preventing Intimidation, Discrimination, and Disruption by The Brennan Center for Justice on Scribd.

3. The Constitution places oversight of voting in the hands of the states.

Another reason state elections officials may have reacted so strongly to the Kobach letter is this: everything (pretty much) related to voting rests with the states.

The Constitution authorizes state legislatures to choose the “times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives” but gives Congress authority to “make or alter such regulations.” Congress has very little authority over state or local elections, which have far more races and measures than the three federal offices: U.S. senator, representative and president.

Congress has passed only a few laws that regulate elections, such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965; the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (Kobach has been overruled by the courts in his attempts to circumvent this law); and the Help America Vote Act of 2002.

The result is a very decentralized election administration system, where no state runs its elections exactly like another state.

4. Some states allow you to register to vote on the day of the election.

Most Americans (3-in-5) believe we should make it as easy to vote as possible. The remainder think your actions should reflect the importance of voting: plan, dadgumit, and register in advance!

A large majority of Democrats (84%) say that voting should be made as easy as possible for citizens. By contrast, just 35% of Republicans favor making voting as easy as possible, while 63% say citizens should have to prove they really want to vote by registering ahead of time. Among independents, more say it should be easy for citizens to vote (57%) than say they should have to prove they really want to vote (41%).

State law hasn’t followed public opinion.

Most states have a voter registration cut-off in advance of election day but a growing number of states have same day voter registration. This means that a citizen, who shows proper identification, can update a voter registration or register to vote on the day of an election.

These are the progressive states as far as voter registration practice (SDVR):

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- District of Columbia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Iowa

- Maine

- Maryland

- Minnesota

- Montana

- New Hampshire

- Ohio

- Vermont

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Want to make it easier to vote in your state? Lobby for change!

5. Three states have open primaries for state and local contests.

If you live in Washington, Louisiana or California, you live in what is effectively an open primary state. In these states, if no candidate wins a majority of the vote in the primary election, then the top two candidates advance to the “general” election, regardless of political party.

As a result, there is no political party registration in Washington, with the exception of every four years for the presidential caucus/primary.

Want to reduce the influence of political parties in your state? Lobby for change!

6. Voter fraud is not a real problem.

The history of voting in the United States is not punctuated by voter fraud: people voting who shouldn’t.

The history of voting in the United States is punctuated by voter suppression: preventing people from voting.

From our origins — when only landed men were able to vote — to Jim Crow; from refusal (or impediments) to reinstate voting rights of felons who have served their time to modern scaremongering that disenfranchises Hispanic voters. Many military and overseas citizens are disenfranchised because of logistical problems in transmitting ballots. Although the HAVA requires states to issue provisional ballots, states are not uniform in how they process them (or when they require one).

Commission criticized

The Trump commission has rightly been criticized for chasing a problem that researchers have shown does not exist. For example, a study of allegations of voter fraud from 2000 to 2014 found only 31 “credible allegations” of voter impersonation out of 1 billion ballots cast.

The Brennan Center provides hard research detailing the missing problem.

After the last election, Brennan researchers interviewed elections administrators from 42 jurisdictions who had conducted the 2016 election.

“Improper noncitizen votes accounted for 0.0001% of the 2016 votes [23.5 million] in those jurisdictions.”

In California, New Hampshire, and Virginia – states called out specifically by Trump – “no official … identified an incident of noncitizen voting in 2016.”

The case of Wisconsin

State senator Dale Schultz (WI-R) spoke to ProPublica about voter suppression efforts in Wisconsin. ProPublica asked Schultz if anyone showed him “compelling evidence” of voter fraud. His answer:

No, in fact, quite the opposite. Some of the most conservative people in our caucus actually took the time to involve themselves in election-watching and came back and told other caucus members that, “I’m sorry, I didn’t see it.”

Schultz asked for three specific examples of voter fraud:

… and all I got was a bunch of hand-wringing and drama-filled speeches about the “buses of Democrats being brought up from Chicago.” I said, “Show me where that was ever prosecuted or even charges brought.” It was crickets. Nobody could give me an answer, and that was both an eye-opening and sad moment for me because I think it finally hit me that time-honored tradition of the “Institution of the Senate” was all but dead.

The Supreme Court will hear a Wisconsin case on partisan gerrymandering in its 2017-2018 term. Gerrymandering — “drawing political boundaries to give your party a numeric advantage over an opposing party” — is another method of voter disenfranchisement with a long (and sordid) history.

Effects of voter ID laws

In 2013, the US Supreme Court, in Shelby County v. Holder, struck down a key part of the Voting Rights Act, one of the most dramatic achievements of the civil rights movement. This decision emboldened those who have sought to disenfranchise voters (using fear as a rhetorical tactic), in large part by passing discriminatory voter ID laws. But “10% of Americans who are fully eligible to vote don’t have the right form of identification” for these new laws, which vary by state. Many of those laws have subsequently been struck down by the courts.

The Brennan Center provides anecdotes illustrating the effects of those voter ID laws.

The Ohioans who, in 2004, took hours off work and waited in line to vote, but had to leave before getting a chance to cast a ballot. The Texas students turned away from voting even though they brought a state-issued university ID as proof of identification. The black churchgoers in North Carolina who used to vote the Sunday before Election Day — until Sunday voting was eliminated in counties across the state. The Wisconsin voter in 2016 who brought three forms of ID to vote but was still turned away from the polls because she didn’t have a driver’s license.

But it also provides hard research detailing the missing problem.

After the last election, Brennan researchers interviewed elections administrators from 42 jurisdictions who had conducted the 2016 election.

“Improper noncitizen votes accounted for 0.0001% of the 2016 votes [23.5 million] in those jurisdictions.”

In California, New Hampshire, and Virginia – states called out specifically by Trump – “no official … identified an incident of noncitizen voting in 2016.”

No one is saying “zero” voting fraud occurs, although 0.0001% is awfully close to zero.