The DNA didn’t match. The witnesses weren’t sure. But the prosecution persisted.

By Christian Sheckler (left) and Ken Armstrong (right) / 07.27.2018

Illustrations by Matt Rota, special to ProPublica

This article was produced in partnership with the South Bend Tribune, a member of ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network.

In 2017, Keith Cooper won a historic pardon — Indiana’s first based on innocence — exonerating him of a shooting that happened two decades earlier, in the city of Elkhart.

But there’s more to Cooper’s story.

It’s a story about how poor policing cost Cooper and his co-defendant, Christopher Parish, years of their lives, leading to one multimillion-dollar settlement with another lawsuit pending. Two officers in the case had long records of misconduct, yet were allowed to remain detectives.

It’s a story about how prosecutors continued to double down on Cooper’s conviction, more than a decade after it unraveled in the face of new evidence.

It’s a story about how, at the height of the 2016 campaign season, Gov. Mike Pence, who was running for vice president, held the power to clear Cooper’s record but refused to do so.

It’s a story about how Cooper and Parish suffered while those in power prospered.

A ‘Fairly Routine Case’

By the next morning, Elkhart police detective Steve Rezutko had been assigned as the lead investigator in the case.

He immediately faced a mystery.

The first evidence technician sent to Kershner’s apartment had been unable to find any blood, spent shell casings or bullet holes. “I walked inside looking for a crime scene,” he wrote in his report, “but one was never located.” A second technician was dispatched. He, too, found no trace of blood or bullets.

In the morning’s wee hours, one tech returned. He scoured the living room. In one corner, it looked as if a chair might have dented the wall. On the floor, scattered among cement dust, he found some metal fragments, apparently from a bullet. But still, even on this third search, no blood.

Rezutko did not focus on the lack of blood. He didn’t even ask the evidence technicians about it, from what he could later recall.

Instead, he focused on an ambiguous statement from a witness.

Late the night before, another detective, Ed Windbigler, had questioned a friend of Kershner’s, Eddie Love, who said he had seen the shooting. Windbigler had asked for details on the robbers, then typed out the witness’ statement. Windbigler wrote:

“I know that I have seen these two guys in the past, I think on Sixth St. and in the area of Prairie and Middlebury. I don’t know their names but the second guy that came into the apartment looks like a guy I know (Chris Parish).”

Confusing as the statement seemed — Love said he didn’t know the robbers’ names, just before naming Parish — the meaning was clear to Rezutko. “I took it as he thought it was Chris Parish. That’s the way I took it,” he would say later.

Elkhart police kept hundreds of old mugshots and Polaroids of people who had been arrested.

To put together a photo lineup, Rezutko rounded up pictures of Parish, who was then 20, taken several years before, when he was a juvenile.

The shooting victim and his family said two black men — one tall and thin, the other short and stocky — forced their way inside and demanded drugs and money.

Using photos of other people as fillers, Rezutko then showed Parish’s mug to Kershner’s mother and girlfriend, according to his reports. Both picked out Parish as the second robber, Rezutko wrote in those reports. The girlfriend wasn’t positive, but the mother was.

Then he visited the hospital, where Kershner put his finger on Parish’s picture.

But despite the importance of this interview — Parish claimed he provided Rezutko an alibi — the details were either unrecorded or unpreserved. Rezutko would later say he had no notes of what Parish told him that day.

Rezutko still had no leads on the other suspect, the tall, thin one.

Keith Cooper, at his home in Illinois, says he wants restitution for all the years he lost in prison. Robert Franklin, South Bend Tribune

Rezutko would later say he had no reason to suspect Cooper of Kershner’s shooting, other than his appearance and the fact he had been arrested for trying to grab a woman’s purse.

“Elkhart, Indiana, doesn’t have a whole lot of tall, 6-foot-4, 6-foot-5 black male robbers running around,” he would say in a deposition.

Rezutko put Cooper’s picture in an array of six photos. He showed the lineup to Kershner, his mother and his friend. All three signed statements identifying Cooper as the gunman.

The detective went to see Cooper in jail. Cooper denied having anything to do with either the Kershner shooting or the attempted purse snatching.

There were “no instructions as to how to do an investigation,” Rezutko would say.

“Detectives did what detectives did.”

Some fellow officers valued Rezutko because he’d built a formidable network of sources on the street — “he knew all the drunks, all the bandits, all the prostitutes,” said a former supervisor, Tom Cutler — and because he was handy in a brawl.

“He’s a big guy, and he’s been in some bar scrapes, and come out of it the winner,” Cutler said.

But Rezutko’s disciplinary record hinted at problems.

In 1987, he failed to arrest a wanted man, ignoring a warrant. In 1990, he left his gun in an unlocked drawer in the police station’s detention area.

In 1991, the police chief gave him a three-day suspension for allowing a robbery suspect to escape by leaving the man unshackled while questioning him.

Four years later, a woman tried to escape after Rezutko failed to properly restrain her. The police chief suspended him for one day.

Beyond those incidents, Rezutko’s conduct with women — including witnesses and informants — raised alarms.

“I think he had a little bit of difficulty in keeping his hands to himself,” Dennis Bechtel, a police chief who supervised Rezutko in the 1990s, said in a deposition.

In April 1996 — six months before the Kershner shooting — a woman filed a complaint against Rezutko, stemming from “improper touching” in an unmarked squad car while he was on duty, according to disciplinary records. That July, Bechtel suspended Rezutko for three days.

Rezutko’s former partner and supervisor, Larry Towns, later offered more details. The woman, Towns said in an affidavit, was a witness. He said Rezutko was in the car with her when a button on his radio was pushed, accidentally broadcasting to other officers what Towns believed to be the sounds of a sexual encounter.

A few years later, he would again face allegations that, Rezutko said in a deposition, “all had to do with sex, innuendo.” He said department officials had talked to several people who reported he either had sex or asked to have sex with them. Rezutko declined to comment for this story.

Towns said Rezutko was reputed among colleagues to have had sexual relationships with confidential informants, including prostitutes, whom he paid with department money.

“He knew all the drunks, all the bandits, all the prostitutes,” a former supervisor said of Elkhart police Det. Steve Rezutko.

AFTER PARISH’S ARREST in the fall, his mother had put up her house to post his $50,000 bond, allowing him to be free pending trial.

Ambrose hit his police lights, busted “a U-turn in the middle of the street,” came back, parked his bumper against Parish’s front door, drew his gun, “and told my kids if they move, that he was going to blow their head off,” Parish said. Ambrose ordered Parish into the police car, saying he had a warrant for his arrest.

Ambrose, in a deposition of his own, picks up the story: “So I placed him in custody, and took him to the police department, at which time they told me that the warrant had been served just like recently, which is what he was telling me also.”

At the station, the police let Parish go.

Parish and his girlfriend filed a complaint against Ambrose for unlawful arrest and conduct unbecoming an officer, prompting an Elkhart police investigation.

For Ambrose, like Rezutko, being investigated was nothing new.

In 1988, two years after joining the department, he was reprimanded for leaving a loaded gun in a squad car’s glove compartment.

The following year, supervisors wrote up Ambrose three times in three months. One time he fixed a friend’s traffic ticket. Another time he either kicked or placed his foot on the head of a man who was handcuffed on the ground and “offering no resistance other than being mouthy,” the disciplinary letter said. “Whatever the act, kicked or placed … it gives us the appearance of ‘goons’ rather than professionals.”

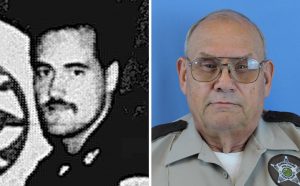

Left: Steve Ambrose, an Elkhart police officer for about 11 years, was suspended for an unlawful arrest of Christopher Parish. Right: Steve Rezutko. Photos courtesy of the Elkhart Truth and St. Joseph County Sheriff’s Department

At some point — the date is unclear — Ambrose also was suspended for moving a jail camera to prevent fellow officers from being recorded, according to records in a lawsuit. Ambrose, in a deposition, said he pointed the camera away when “a fight broke out.”

In 1992, the police department promoted Ambrose to detective.

In May 1995, Ambrose killed a 22-year-old black man, Derrick Conner, shooting him five times during a chase. Police said Conner was armed. Conner’s family disputed that. A grand jury declined to indict Ambrose, but the shooting prompted a lawsuit against the city, eventually settled for $400,000.

Ambrose did not respond to interview requests for this story.

ON FEB. 10, 1997, at the Elkhart County Jail, Ed Windbigler — the detective who took Eddie Love’s statement mentioning Parish — sat down with an inmate named Debery Coleman.

Less than two weeks before, Coleman had pleaded guilty to aggravated battery, a felony for which he could get 20 years. Now, his sentencing pending, he claimed to have information that could help the police.

Windbigler, a department veteran of 10 years, had previously served in the Marine Corps, where, as a military police officer, he was part of a detail that protected President Ronald Reagan during helicopter flights. At the police department, he’d made sergeant in less than five years before moving to the detective bureau.

The week before he met with Windbigler in February 1997, Coleman had been placed in a cell with Keith Cooper. As the two talked, Coleman said, Cooper confessed to shooting Kershner, saying he and Parish had plotted the robbery to get some marijuana.

Coleman was offering himself up as a jailhouse informant. Informants typically relay damning information learned from other inmates in exchange for shorter sentences or dropped charges.

But the police report of this exchange — written by Windbigler, signed by Coleman — said no such quid pro quo was in place here. “Detective Windbigler has not made me any promises for any information that I may have,” the statement said.

THE SAME WEEK Coleman was placed in Cooper’s jail cell, a detective delivered two packages to the Indiana State Police crime lab. One held a hat collected from Kershner’s apartment, the other samples of Cooper’s DNA.

Kershner’s mother and friend told police the tall robber was wearing the hat, and it came off during the struggle. The hat was black, made of cloth or leather, with a vinyl bill. On the front, rhinestones formed the letter J.

A few weeks after the shooting, Rezutko had dismissed the hat’s value, according to Kershner’s mother.

“I asked him about the hat, did they get any fingerprints off the hat or any DNA or anything, and he dismissed me and said that I had been watching too many cop shows, that the hat was useless and made me feel like an idiot,” she would say later in a deposition.

An analyst cut two pieces from the hat. The DNA sample from one cutting was too limited for comparison, given the science at the time. But a good sample was obtained from the sweatband, suitable for testing against Cooper’s genetic profile.

The victim testified she had no doubt Cooper was the man who had tried to grab her purse. “If I wasn’t a hundred percent sure, I wouldn’t be here,” she said.

Cooper had been arrested soon after the crime occurred, about four blocks away.

Cooper testified he was innocent. He said he had left his apartment that morning between 11 and 11:30 to get his car fixed. He needed a new power steering belt. He was unemployed — and had been, for months — but had a money order for $88, which he had planned to use for rent.

He dropped off his car at a gas station, cashed his money order at a market, and was walking back to the gas station when he was arrested, he said.

The police didn’t put Cooper in a live lineup or his picture in a photo array. Instead, after making the arrest, an officer had put Cooper, handcuffed, in the back of his squad car. The officer then drove past the victim — slowly, without stopping. She looked through the car’s window and told police he was the man.

“What he did is the most suggestive way to try and show someone had committed a crime,” Cooper’s lawyer told the jury. “I would expect better from the police department. I can’t believe [the officer], and his eight years on the force, doesn’t know better than to do something like this. I can’t believe the police are going to be trained that way.”

‘My Testimony Shouldn’t Be Taken Seriously’

IN SEPTEMBER 1997, Cooper — eight months after his arrest — returned to court for the Kershner shooting.

This time, he waived a trial by jury, leaving Circuit Judge Gene Duffin to weigh the evidence.

At Cooper’s trial, three eyewitnesses — Kershner, his mother and his friend, Eddie Love — took the stand. Questioned by deputy prosecutor Michael Christofeno, each implicated Cooper.

Kershner’s mother, Nona Canell, would later say she had doubts Cooper was the shooter, and shared them with Rezutko. She said Rezutko had her sit in the courthouse hallway before trial so she could see Cooper coming in. “I swore that was him,” Canell would say in a 2008 deposition. “Steve Rezutko told me he did his job. This was the guy, and I believed him.”

The prosecution’s next witness was Debery Coleman, who had claimed in February that Cooper confessed to him. Now, at trial, Coleman refused to talk about their jailhouse conversation.

Duffin ordered Coleman to answer or be held in contempt, lengthening his prison sentence and ruining his chances at early release.

“I’ll be in contempt,” Coleman said.

Duffin gave him 90 days in jail.

In the end, Coleman’s silence meant little. Duffin allowed the alleged confession in through testimony by Windbigler, the officer who typed Coleman’s statement.

Lisa Black, the state police DNA analyst who tested the shooter’s hat, wasn’t called to testify. Instead, the two sides presented a stipulation, outlining what they agreed Black would have said.

The stipulation said nothing of how Black had excluded Cooper as the source of the DNA found on the hat’s sweatband. Instead, it said: “The expert opinion of Lisa Black is that neither Keith D. Cooper nor any other person can be eliminated as having possibly worn the hat.”

An appeals lawyer would later write that Cooper’s lawyer, Jack Smeeton, had “stipulated away the best defense available to Mr. Cooper, that his DNA was not found in that hat.”

Smeeton, in a recent phone interview, said he remembered few details of the case and declined to discuss the criticism of his work.

“Clients blame their lawyers for things all the time when they don’t go right,” Smeeton said. “Nothing new.”

Come the defense’s turn, Cooper took the stand. He denied robbing or shooting Kershner. He denied confessing to Coleman. He said he didn’t know Parish.

There was one more witness: Jason Ackley, the boyfriend of Kershner’s mother. He hadn’t seen the robbery, but he told police he had heard it from the bathroom, where he was changing clothes.

On the day of the trial, Ackley wasn’t expecting to testify, he would say later, but Rezutko asked if he could listen to Cooper’s voice and say whether it sounded like the gunman. “It will be the final thing to get him convicted,” Ackley claimed Rezutko told him, according to a later affidavit.

Cooper’s lawyer objected to the voice identification, but the judge allowed it. The prosecutor fed Cooper lines used by the shooter.

“Let me hear you say the phrase, ‘If you try to get out, I’m gonna kill you.’”

Cooper said it.

Christofeno dictated another line, then added: “Mr. Cooper, say it with a little more enthusiasm.”

Ackley said Cooper’s voice matched the robber. But his story would later change.

“I would have identified any voice,” he would later say in his affidavit. “My testimony shouldn’t be taken seriously. I did it to help the police and my girlfriend’s family.”

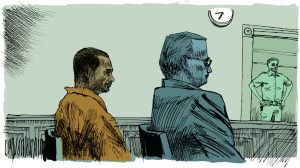

Nadia Sussman/ProPublica

PARISH, CHARGED WITH TWO Class A felonies in the Kershner shooting, was looking at a possible 50 years.

But the state offered a deal. If Parish would plead guilty to a lower-level felony — “any Class C felony that he would like,” a prosecutor wrote in a letter — he might serve as little as one year.

“I wasn’t going to take a deal and didn’t take a deal,” Parish would say later. “It wasn’t going to happen.”

In June 1998, Parish went to trial. The prosecutor was again Christofeno.

With no physical evidence tying Parish to the crime, the state’s case hinged entirely on eyewitness testimony.

Early in the investigation, Kershner and his mother had offered vague or inconsistent descriptions of the short robber. Kershner’s girlfriend had said Parish might be him, but she wasn’t sure. Now, all three said they had no doubt Parish was the man.

Elkhart, in northern Indiana, has a population of about 50,000. Its nicknames are “City with a Heart” and “RV Capital of the World.” Robert Franklin, South Bend Tribune

In court, Kershner said that when he selected Parish’s photograph in the hospital, he was a “million percent positive.”

When Rezutko took the stand, he was asked about Kershner’s condition when he made that identification.

“He was in a great deal of pain. He had been in surgery. He was fairly incoherent to talk to,” Rezutko said.

That day in the hospital, Rezutko testified, he had shown Kershner an up-to-date photo of Parish, taken when Parish was arrested for the robbery.

But that wasn’t possible. Rezutko showed Kershner the photo on Oct. 30. Parish was arrested on Oct. 31.

Asked about the photo he had shown Kershner’s mother and girlfriend on Oct. 30, Rezutko said that picture of Parish had been taken six years before the shooting. That meant Parish would have been only 14 or so at the time.

Questioning Rezutko proved a challenge because critical records were either missing or had never been created.

Rezutko’s report of what Kershner had told him after getting out of the hospital was missing. So was Rezutko’s initial closure report, summarizing the evidence against Parish.

For both reports there had been three copies, one each for the prosecutor, the master file and the investigator. In each case, all three copies were missing.

The defense presented seven alibi witnesses. The night of the robbery, they testified, Parish had been in Chicago at a family gathering. “Definitely positive,” one defense witness said. “Absolutely positive,” another said.

By 2002, five years into Cooper’s prison sentence, forensic science had advanced. Polansky asked Cooper what he thought about re-testing the DNA from the black hat adorned with the distinctive “J.”

Cooper’s response was unequivocal: Run the test. “This new/corrected evidence will exonerate me,” he wrote in a letter to Polansky.

“The DNA profile obtained from one sample of the hat,” Black reported, “was found to be consistent with Michigan Department of Corrections inmate Johlanis Cortez Ervin.”

Ervin, then 24, had been convicted of a 2002 murder in Benton Harbor, Mich., about 50 miles from Elkhart. Police said Ervin fired into a group of people, killing a bystander, after a dispute over a front-porch dice game.

Ervin’s jail records listed him as 6-foot-2, weighing between 155 and 190 pounds.

Also convicted in the 2002 shooting was his brother, Michael Ervin, listed as 5-foot-7 and 170 pounds.

One was tall and thin, with a name that started with “J.” The other was short and stocky.

On Aug. 26, 2004 — after six years in prison — he had a hearing in Elkhart Superior Court. In the courtroom of Judge Stephen E. Platt, Parish put nine witnesses on the stand. Three said the crime had taken place not inside Kershner’s apartment — as the prosecution’s witnesses had claimed at trial — but outside, in or near the apartment complex’s laundromat.

How do you know that, the prosecutor asked one witness, Stellana Neal.

“Well, I saw him go to the laundromat,” she said. “And before he went to the laundromat, he was not shot, and when he come back from the laundromat, he was shot.”

Mark Doty, Parish’s trial lawyer, testified he had assumed the shooting took place inside the apartment, even though no blood had been found there. He hadn’t asked around, to investigate any other possibility.

When the last witness stepped down, Platt left no doubt which way he was leaning.

“I think the newly discovered evidence argument seems to have a lot of merit,” he said.

Platt said he didn’t want Parish “sitting in jail, if in fact he’s entitled to be released.”

The judge asked for written arguments from both sides.

The deputy prosecutor opposing Parish’s petition was Charles C. Wicks, who, at the time, was chairman of the Elkhart County Republican Party.

On Oct. 4, six weeks after the hearing, Wicks filed the prosecution’s argument.

Stellana Neal, Wicks wrote, admitted at the hearing that she had “ingested marijuana at the time of the shooting which may have clouded her judgment.” This wasn’t accurate. Neal testified she had smoked marijuana after the shooting, not before.

At Parish’s trial, the victim’s mother had “identified Christopher Parish as the shooter,” Wicks wrote. This wasn’t true. She had identified Parish as the shooter’s accomplice. Parish, Wicks wrote, had also been identified as the shooter by Kershner’s girlfriend (not true) and one of his friends (not true).

Platt issued his ruling three days later. Saying he had “carefully examined” the trial transcript, Platt denied Parish’s appeal — and adopted, wholesale, the prosecution’s findings of fact as his own. The prosecutor’s words became the judge’s words.

When they were arrested, Keith Cooper and Christopher Parish were brought in to the Elkhart police station. Robert Franklin/South Bend Tribune

Parish’s lawyer filed a motion to correct errors — only to get more in return. Wicks’ response to the motion said the defense had called 12 alibi witnesses. (There had been seven). The judge’s order denying the motion said jurors had had a chance to observe witness Eddie Love when he testified at Parish’s trial. (They hadn’t, because he didn’t.)

Parish received the judge’s ruling in the prison mail. “It ripped my soul,” he’d say.

In January 2005, Parish received a court-appointed lawyer to appeal Platt’s ruling. But Parish opted to go it alone.

He collected what he needed for the appeal: transcripts, exhibits, the clerk’s record. He filed notices or motions in February, March, April, May. He wrote an 88-page brief with 99 citations to other cases. In June he filed it — and waited.

WHILE PARISH HAD ARGUED his case to Judge Platt, Cooper had done the same to Judge Duffin, presenting evidence the shooting happened outside and that DNA linked the shooter’s hat to a convicted murderer in Michigan.

In April 2005, Cooper notified Duffin that he had no more evidence to offer.

In December, Cooper’s lawyer, Polansky, got a call from Duffin. Now that Parish’s conviction had been overturned, the judge was offering Cooper two options, Polansky told his client in a letter.

Duffin could vacate Cooper’s conviction. Cooper, with no money to bond out, would remain in prison or jail while awaiting word on whether prosecutors would retry him.

Or the judge could modify Cooper’s sentence to time served. Cooper would go free, but his robbery conviction would still stand.

Polansky had no idea why the judge was conveying this offer. Out-of-court deals are typically worked out between the prosecution and defense, and then submitted to a judge for approval.

“That’s the only time I’ve ever had that happen in my career,” he says of Duffin’s call.

In a recent phone interview, Duffin said he did not remember calling Polansky. He said making such an offer independently would have been “totally improper.” “I would presume there was a prosecutor either on the phone with us … or in my office,” he said.

At that time, the head prosecutor in Elkhart County was Curtis Hill, who had joined the office fresh out of law school in 1987. Hill won election in 2002 after defeating a fellow deputy prosecutor — Michael Christofeno, who had tried Cooper and Parish — in the Republican primary. Hill ran an aggressive law-and-order campaign, promising to run drug dealers out of town. (“We’ll chase them all over the county, and then out,” he said.)

Cooper had never wavered on his claim of innocence, but the risk with a new trial was great, and there was no saying how much time prosecutors would take to decide whether to retry him or cut him loose.

The eight and a half years in prison had taken their toll. Cooper says he’d heard his wife and children were struggling in Chicago.

“In answering your question about the choice proposed by Judge Duffin, my answer is yes,” Cooper wrote Polansky. “In return Judge Duffin can keep his conviction, and I’d have my freedom!”

Cooper grabbed his box of legal mail. The guards put Cooper in a van and drove him 80 miles to a train station in South Bend, where he boarded the train to Chicago.

Nadia Sussman/ProPublica

Parish, too, had received an offer.

After his conviction was overturned, Elkhart County prosecutors told Parish that if he pleaded guilty he could stay free — serving no more time than he already had.

Parish refused.

‘He Is Innocent of That Crime’

One of Parish’s lawyers deposed Ed Windbigler about his interview with witness Eddie Love, who had said he didn’t know the robbers’ names but that one looked like Parish. Windbigler by now was a lieutenant.

Windbigler said he didn’t recall taking Love’s statement, but reading it now, he assumed he had made a mistake in how he took down Love’s words.

“I think this is poor grammar on my part,” Windbigler said. “To me he’s saying, I think it was Chris Parish.”

Parish’s lawyer pressed. “It’s more than a mistake in grammar, isn’t that correct, it’s actually contradictory information the way that you are reading it?”

“Correct,” Windbigler said.

Love, when deposed, denied telling police that Parish was the second robber. He also denied saying the second robber looked like Parish.

“The police said that, and they said that I said that, but I ain’t said that,” Love said.

The lawyers deposed Rezutko in the spring of 2008, almost 12 years after he investigated the Kershner shooting.

Asked about photo lineups, Rezutko said Elkhart police had no formal policies on how to put them together.

In Parish’s case, Rezutko said, he pulled photos of people who had comparable features to Parish.

“Well, you try to get them as similar as possible,” Rezutko said.

Otherwise, the array is suggestive: the witness can just pick out the lone photo with certain recognizable characteristics.

But Parish’s lawyer later presented Rezutko with a photo array the detective had prepared while investigating Cooper, Parish’s alleged accomplice. In this array, the six men did not look alike. One man had a big mustache. One was bald.

“I’m just trying to get people who look different as opposed to people who all looked alike,” Rezutko said.

Why, the lawyer asked, would you sometimes want them all the same, and sometimes all different?

“There would be some reason I did that. I just can’t tell you what it is. I don’t remember,” Rezutko said.

“Is there any doubt in your mind that Parish had anything to do with this?” Parish’s lawyer asked.

“Do I have to answer that?” Rezutko said. Then he said: “Yeah. Not initially. Not initially during the investigation. But at trial, I had a tendency to believe the alibi witnesses. I believed when the trial was over that Chris was going to be exonerated because I believed his alibi witnesses.”

If he had been a juror, Rezutko said, he wouldn’t have voted to convict.

This was the only case in his entire career, Rezutko said, where he had doubts that the right person was on trial.

THROUGH PARISH, THE LAWYERS at Loevy & Loevy learned of Cooper’s case. They sent Elliot Slosar — a law student and investigator — to learn more.

The firm took Cooper on as a client. Because he had taken the deal for a modified sentence instead of demanding a new trial, it seemed his best shot at clearing his name would be a pardon from the governor.

Slosar and his associates collected written statements from Kershner and his mother, saying they no longer believed Cooper was the shooter. Cooper’s team turned their attention to Debery Coleman, the jailhouse informant.

In early 2009, Coleman signed a seven-page affidavit saying Rezutko had him placed in a special cell, called the “hole,” with Cooper and instructed him to get information from his new cellmate — an arrangement that can violate a defendant’s right to have a lawyer present for questioning.

Cooper did not confess, Coleman’s affidavit said. Instead, he had simply explained the police version of the crime.

Coleman met with Windbigler at the jail and shared what Cooper had told him. To fill in gaps in that account, Coleman said, Windbigler fed him other details from the shooting.

In exchange for the statement, Coleman said, Windbigler offered to get his prison term knocked down to six years. With good behavior and credit for time served, he could be out in less than two.

But come time for sentencing, Coleman received almost 14 years.

Seven months later, Coleman was brought back to Elkhart County for Cooper’s trial, only to be held in contempt.

Coleman’s affidavit completed Cooper’s pardon petition, which was submitted to the Indiana Parole Board on March 4, 2009.

PARISH’S LAWSUIT AGAINST THE CITY of Elkhart and Rezutko went to trial in the fall of 2010, in the U.S. District Court for Northern Indiana.

Before the first witness was called, the defendants’ attorneys asked Judge Rudy Lozano to exclude certain evidence. They wanted the jury to hear no mention of the DNA results or Johlanis Ervin. The judge agreed — and even expanded his order to Ervin’s short, stocky brother, whom Kershner’s mother said was a dead ringer for Parish. He also excluded evidence about Keith Cooper.

To Parish’s lawyers, that evidence was critical. If the eyewitnesses were wrong about Cooper, how could their testimony about Parish be trusted? And without the evidence about the DNA and the Ervins, how would jurors grasp the strength of Parish’s innocence claim?

While siding with the city, the judge suggested that maybe the trial should be postponed, to give him more time to think about this.

“[C]onsider the possibility that I can give a screwball ruling,” the judge told Elkhart’s and Rezutko’s lawyers. “And I’ve done that from time to time over 24 years. Do you really want this case reversed?”

The lawyers said they wanted to proceed.

Former Elkhart police captain Larry Towns testified that Rezutko, who was once his partner, conducted suggestive photo lineups. He rushed to judgment. He would take multiple statements from witnesses, and “they would always have something different in them.”

Sometime before the Kershner shooting, Towns, as Rezutko’s supervisor, had removed Rezutko from being lead on any homicide investigations. Towns said he had asked the police chief to remove Rezutko from detective work altogether, but the chief declined.

Rezutko, on the stand, fielded one question after another about records that couldn’t be accounted for.

“Where is the photo lineup with Mike Kershner’s signature on it?”

“I have no idea.”

Where’s the report from when you interviewed Parish?

“I have no idea.”

Even what was thought to be known needed revisiting. In his original reports — and in his testimony at Parish’s 1998 criminal trial — Rezutko had said Kershner’s mother and girlfriend had identified Parish using the same photo, one taken in 1990 when Parish was around 14.

But in 2009 another police officer had discovered a sealed evidence bag revealing the actual photos shown. The mother had identified Parish in a photo from 1991. The photo picked by the girlfriend was from 1993. The photos were not the same. Nor did Parish look the same in them. “Well, they don’t look alike, if that’s what you’re asking me,” Rezutko testified.

As the trial went on, Parish’s lawyer kept asking the judge to reconsider and allow in the evidence he had excluded. The judge kept refusing. The jurors heard about the evidence used to convict Parish. They heard little of how the state’s case had since collapsed.

Sometimes the people in Rezutko’s photo lineups looked alike. Sometimes they looked different. Rezutko couldn’t explain why.

Parish appealed. His lawyers called the damages so low as to be “totally off the charts.”

Parish’s lawyers pulled up cases from across the country in which a wrongful conviction had been proved at trial. Juries in 23 other cases had awarded, on average, $949,831 for each year spent in prison. Parish’s jury had awarded about $9,000 per year.

In September 2012, a federal appeals court heard the case. Elkhart’s case was argued by Martin Kus, a LaPorte attorney who had also represented the city at trial.

Why, the judges asked, did the jury not get to hear that the victims now doubted Parish’s guilt?

“We would have had two and maybe three trials within our trial,” Kus said.

“So what?” Judge Ilana Rovner said. “You would have had justice, perhaps.”

The additional evidence might have caused confusion, Kus told the judges.

“What’s the confusion?” asked Judge Richard Posner.

“Well, because we’re introducing the three letters, DNA, eight years after the event,” Kus said.

“So what?” Posner said.

The only explanation for that low damage award, Posner said, was that the jury thought Parish was guilty.

He told Kus: “You’ve made a big mistake. You should not have defended this. … Your position is frivolous.”

Posner asked Parish’s lawyer, Jon Loevy, about Johlanis Ervin, the man linked to the shooter’s hat.

“Is he being prosecuted? Has the statute of limitations run or what?”

“No it hasn’t,” Loevy said. “And it’s a shame that he’s not being prosecuted. That would require the system to admit it made a mistake.” (Ervin did not respond to a letter seeking comment for this story.)

In 2014, the city of Elkhart settled with Parish for $4.9 million.

ON FEB. 3, 2014 — almost five years after Cooper filed his pardon request — he got his hearing before three members of the Indiana Parole Board.

The chairman was a Republican attorney who had worked as an aide to a lieutenant governor. Another member, a Republican appointed to the board by then-Gov. Mike Pence, had been an administrator for the Indiana Supreme Court. The panel’s lone Democrat, another Pence appointee, was previously a prosecutor in Indianapolis.

Cooper asked the members to put themselves “in my shoes.” He recited the chain of events, starting with his purse-snatching arrest, that landed him in prison for shooting a man.

Throughout the Cooper and Parish cases, misinformation had abounded. Now, before the parole board, there was more — with Cooper as the source. His written petition to the parole board had said the victim in the attempted purse snatching “did not identify Mr. Cooper in court as the perpetrator, which is why Mr. Cooper was acquitted.” But she had identified him in court, according to a trial transcript recently created at the request of ProPublica and the South Bend Tribune.

Cooper told the parole board he had been working two jobs when arrested. But he had actually been unemployed, according to his trial testimony. Cooper told the board (and subsequently, at least two newspapers) a story of being arrested at a train crossing. That, too, was contradicted by the trial transcript.

Slosar, asked recently about these discrepancies, said, “I think science shows that witnesses’ memories certainly don’t improve decades later.” But, Slosar said, Cooper’s fundamental account of being picked up and arrested, simply by virtue of being a tall black man in Elkhart, has never changed.

At the parole board hearing, Kershner provided a video statement in Cooper’s favor, and Kershner’s mother spoke to the board in person. She broke down in tears and apologized to Cooper for helping put him in prison.

The following month, the board voted unanimously in favor of Cooper’s pardon. Its recommendation would be forwarded to Pence. At the hearing, the board chairman had offered a word of caution: Cooper could be in for a long wait.

“Traditionally governors in the past have taken long periods of time in making their decision,” he said, “and by long periods of time it could easily be several months.”

BY 2016, PENCE HAD YET TO ACT on Cooper’s petition for a pardon.

The previous September, the city of Elkhart had sent the governor a 38-page plea to reject the petition. The memo was written by Martin Kus, the attorney who had defended Elkhart against Parish’s civil suit.

Kus argued that Cooper’s motive was “purely financial,” saying he needed the pardon to “file a multimillion dollar civil rights suit against the City and its officers.”

In 1997, while awaiting trial, Cooper had punched a fellow inmate, breaking his jaw. He subsequently pleaded guilty to battery, a felony. That conviction, Kus wrote, meant Cooper’s voting rights and job prospects would still suffer even if he were pardoned of the robbery.

Kus wrote that when Cooper took the deal in 2006 that set him free, he “accepted guilt without objection” in the Kershner shooting. But Cooper had entered no plea of guilt. He had made no admission. He had simply opted for a reduced sentence rather than a new trial.

Kus dismissed allegations of police misconduct and wrote that Kershner and his mother recanted only because Cooper’s lawyers pressured them with DNA evidence that they claimed had exonerated their client. That DNA evidence, linking the shooter’s hat to Johlanis Ervin, in no way cleared Cooper, Kus wrote.

More than one person could have worn that hat, Kus wrote. He found an article on HowStuffWorks.com about criminals planting DNA evidence to mislead police. “In 1992,” Kus wrote, quoting the article, “Canadian physician John Schneeberger planted fake DNA evidence in his own body to avoid suspicion in a rape case.”

“The City does not suggest that Cooper planted fake DNA,” Kus wrote. But, he added, experts urge “caution against relying upon a lack of finding DNA samples on the item as proof that a party did not touch or wear it as suggested by Cooper.”

Kus also chafed at the term “exoneration” — Cooper’s attorneys, he said, had woven the word into his pardon petition “as an incantation of sorts” to mislead the governor, though he had never been “proven innocent” in court.

The city paid $15,000 for the memo and related work opposing the pardon, according to records.

The memo, which has not been reported on before, was obtained earlier this year by a South Bend Tribune reporter. (It was an attachment to emails disclosed by the Elkhart County Prosecutor’s office in response to a public records request.) “Oh my god, I’ve never seen this,” Cooper’s attorney, Elliot Slosar, told the reporter when asked about the document.

In the summer and fall of 2016, pressure mounted on Pence to act, with several newspapers publishing editorials calling on him to grant Cooper’s pardon request. A Change.org petition, urging Pence to “pardon an innocent man,” amassed 113,000 signatures.

Cooper’s supporters extended the pressure to the Elkhart County Prosecutor’s office, urging Hill to endorse the pardon. Hill bore some responsibility for Cooper’s situation, they said, because he signed off on the 2006 deal that kept the robbery conviction intact.

By this time, Hill was in the middle of a campaign for Indiana attorney general, the state’s highest law enforcement position. That summer, when Pence cut the ribbon on Donald Trump’s new Indiana campaign headquarters, Hill stood at his side, his hand on Pence’s back.

Curtis Hill, pictured with Vice President Mike Pence at a rally this year in Elkhart, was running for Indiana attorney general while Cooper’s pardon petition was pending. Carolyn Kaster/AP Photo

Christofeno, the former prosecutor, was now among Cooper’s supporters. In 2016 he wrote to Pence, saying: “Justice demands that Mr. Cooper be pardoned.”

Finally, on Sept. 20 — 30 months after the parole board recommended that Cooper be pardoned — Cooper got a response. The new statement came neither from Pence nor Hill, but from Mark Ahearn, the governor’s general counsel. Before the governor would consider the pardon further, Ahearn wrote, Cooper would need to prove he’d exhausted all his options in the courts.

On Oct. 3, Slosar followed Pence’s directive by filing a new post-conviction petition in Elkhart Circuit Court. Hill’s chief deputy prosecutor, Vicki Becker, filed an objection three weeks later, arguing Cooper had not followed the proper procedure to file a new appeal.

Slosar believed the prosecutors were delaying Cooper’s appeal over politics. Cooper was an “innocent man caught in limbo due to election season,” Slosar wrote in his response to Becker’s objections.

“[E]lected prosecuting attorney Curtis Hill is in the midst of a race to become Indiana’s attorney general,” Slosar wrote, “and as such, does not want to take a formal position prior to his constituents voting on November 8, 2016.”

In an email to Slosar, Becker chided him for his allegations of political motives. “A cautious reading of the Indiana Rules of Professional Conduct may be in your best interest,” she said, “if you intend to continue to make other accusations that are not based in fact or evidence.”

When Hill’s staff notified him that Slosar had criticized the prosecutor’s office in an interview with a reporter, Hill talked of trying to revoke Slosar’s temporary admission to practice in Indiana, known as pro hac vice.

“I believe we should file a disciplinary complaint and seek revocation of his pro hoc (sic) vice,” Hill told Becker in an email. “Talking to him is a wasted excercise (sic).”

Becker replied: “Slossar (sic) is an idiot.”

On Nov. 2, Becker said in a court filing that Cooper’s appeal was “completely without merit.” The next day — five days before the election — Hill, Becker’s boss, issued a press release.

“I believe he is innocent of that crime,” Holcomb said of the long-ago robbery.

Speaking to reporters in Chicago the next day, Cooper said he was thankful Holcomb “had the heart to do what Pence couldn’t do.”

At the prosecutor’s office in Elkhart, an employee sent Vicki Becker an email with a link to a video of the press conference.

“Ignorance is bliss,” Becker replied.

Three days later, the city of Elkhart’s top lawyer emailed Becker.

“We were successful in getting Governor Pence to not pardon Keith Cooper, but that was not the case with Governor Holcomb,” Vlado Vranjes, the city’s corporation counsel, wrote. “With the Governor’s action, I now expect Mr. Cooper to file suit against the City and its police officers.”

THE WEATHER WAS GRAY AND CHILLY on March 23, 2017, as Keith Cooper walked into the Elkhart County Courthouse for what he hoped was the last time.

Holcomb’s pardon had cleared Cooper’s name. Now, at this hearing, Cooper wanted Judge Duffin to expunge all records the conviction had ever happened.

Cooper was represented by Slosar, and Becker appeared for the state.

Becker acknowledged the governor’s executive order required the court to wipe the felony from Cooper’s record. But she said Holcomb had relied on misinformation, and the pardon had deprived the state of a chance to question witnesses about why they had recanted.

In addition to the conviction, Cooper wanted the record of his arrest expunged. Under the law, an arrest could be cleared only if someone’s conviction had been overturned on appeal. Slosar argued that a pardon based on innocence was no different than a reversal in court. But Duffin questioned the pardon’s basis.

“The governor did pardon him,” the judge said, “but I’m telling you I see nothing in the pardon that says he found the defendant innocent.”

Becker attacked Christofeno, the former prosecutor, who was now a judge, over his letter supporting Cooper’s pardon, suggesting he either prosecuted Cooper in bad faith in 1997 or his turnabout was dishonest.

“Why he would put in this letter that the absence of Mr. Cooper’s DNA on that hat exonerates him is a question, perhaps, that needs to be raised with the ethics board,” Becker said at the hearing.

Becker and Christofeno both declined to be interviewed for this article. So did Hill and former deputy prosecutor Wicks.

Duffin granted the expungement of Cooper’s conviction but would later refuse to expunge the arrest.

On a sidewalk at one end of the courthouse, Cooper celebrated.

At the other end, Becker met with reporters. She said it was important Cooper’s arrest record remain intact so that, if he encountered the law again, police would know he’d had trouble before.

“Hopefully he will be a productive member of society,” Becker said, “and hopefully he will not be a threat to my community ever again.”

CHRIS PARISH NOW LIVES in Indianapolis, where he owns a barbershop he named Champz. He also owns rental properties in both Indianapolis and Elkhart, where he occasionally travels to change a water heater or fix a sink. He said he doesn’t worry about returning to Elkhart. “The cops on the force now — they don’t know me, I don’t know them,” he said in a recent interview.

After being united as co-defendants for so many years, Parish and Cooper finally met at a Christmas party in 2016 at Loevy’s law offices, Parish said. Cooper told Parish at the party: If not for you, I’d probably still be in prison. “He thanked me like 99 times,” Parish said.

Christopher Parish, at the barbershop he owns in Indianapolis, says he’s not afraid of returning to Elkhart despite all that happened there. Michael Caterina/South Bend Tribune

Cooper lives in a modest house on a quiet cul-de-sac in Country Club Hills, Ill., south of Chicago. While his wife, Nicole, works, he stays home. He walks his grandchildren to the bus stop. He says he’s working on a book about his case.

Cooper’s pardon was Indiana’s first for innocence. But last year, on Nov. 20, Gov. Holcomb pardoned six more men for turning their lives around. One counsels at-risk kids. Another became a pastor. “Holcomb doubles Pence’s 4-year total of pardons in one day,” The Indiana Lawyer’s headline said.

In January, the city filed its initial response, denying any police misconduct or that Cooper was wrongly convicted.

In the fallout from the Cooper and Parish cases, the city’s legal fees have, to date, reached almost $300,000 — and that doesn’t count the costs covered by insurance. At least 19 attorneys have shown up in court or billing records as representing Elkhart or its police officers in the lawsuits filed by Parish or Cooper, or in litigation over which insurance company, in a federal judge’s words, “ends up holding the bag.” Ten insurance companies that had policies covering Elkhart over the years have battled in court over which must pay.

Keith Cooper now lives in Country Club Hills, Illinois. Robert Franklin/South Bend Tribune

Johlanis Ervin, the convicted killer whose DNA was found on the “J” hat, has not been charged with Kershner’s shooting.

During an interview earlier this year, Cooper reflected on his years behind bars and those he spent waiting for his exoneration. Those two decades were kinder to many of the people involved in the case.

Steve Rezutko quietly resigned in 2001, while facing an internal investigation into allegations of inappropriate sexual relationships. “I didn’t want to put up with defending it,” he said later in a deposition.

Rezutko’s last day was Oct. 12, 2001. That November, he took a job as a jail officer for the St. Joseph County sheriff’s department, where he worked until he retired this May.

Ambrose was granted a medical disability retirement in April 1997. He currently works as safety manager for a company that makes doors, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Ed Windbigler, who took the statement jailhouse informant Debery Coleman later recanted, is now Elkhart’s chief of police.

Michael Christofeno, who prosecuted Cooper at trial, is now Elkhart Circuit Court judge, presiding over the county’s most serious criminal cases.

Charles Wicks, who misstated facts in his opposition to Parish’s post-conviction petition, is now an Elkhart Superior Court judge.

“Anybody who had a part in my case, look at their careers,” Cooper said. “They all been promoted.”

Nadia Sussman/ProPublica

Originally published by ProPublica under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States license.