Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Pre-Columbian Era

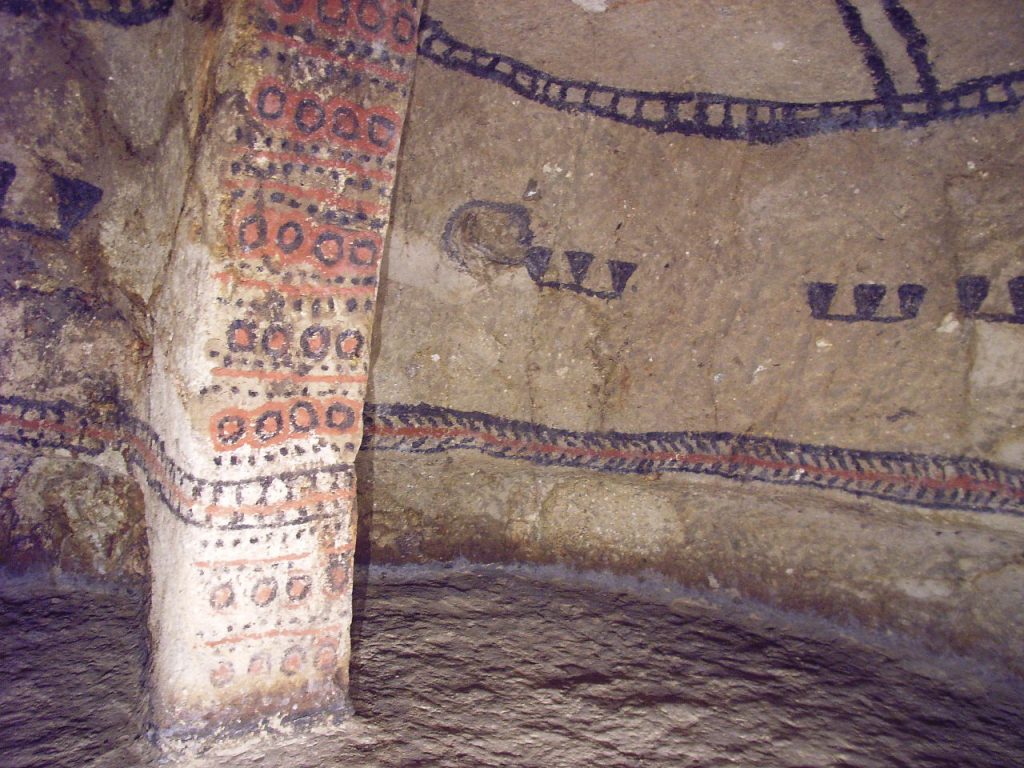

The first humans are believed to have arrived in the area from Central America about 20,000 B.C.E. Circa 10,000 B.C.E., hunter-gatherer societies existed near present-day Bogotá that traded with one another and with cultures living in the Magdalena River Valley.[1] Further waves of Mesoamericans—indigenous peoples of Central America—arrived between 1,200 and 500 B.C.E. and introduced maize. The Chibcha people came from present-day Nicaragua and Honduras between 400 and 300 B.C.E. They grew potatoes, corn, and other crops; developed irrigation systems; mined emeralds and salt; and built roads and suspension bridges.

Within Colombia, the two cultures with the most complex power structures were the Tayronas on the Caribbean coast and the Muiscas in the highlands around Bogotá, both of which were of the Chibcha language family. The Muisca people are considered to have had one of the most developed political systems in South America, after the Incas.[2]

Colonial Era

Spanish explorers made the first exploration of the Caribbean littoral in 1500 led by Rodrigo de Bastidas. Christopher Columbus navigated near the Caribbean in 1502. In 1508, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa began the conquest of the territory through the region of Urabá. In 1513, he was also the first European to discover the Pacific Ocean, which he called Mar del Sur (or “Sea of the South”) and which in fact would bring the Spaniards to Peru and Chile.

In 1510, the first European city in the Americas was founded, Santa María la Antigua del Darién. The territory’s main population was made up of hundreds of tribes of the Chibchan and “Carib,” currently known as the Caribbean people, whom the Spaniards conquered through warfare. Resulting disease, exploitation, and the conquest itself caused a tremendous demographic reduction among the indigenous peoples. In the sixteenth century, Europeans began to bring slaves from Africa.

Independence from Spain

Since the beginning of the periods of conquest and colonization, there were several rebel movements under Spanish rule, most of them either being crushed or remaining too weak to change the overall situation. The last one, which sought outright independence from Spain, sprang up around 1810, following the independence of St. Domingue in 1804 (present-day Haiti), which provided a degree of support to the eventual leaders of this rebellion: Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santander, who became the first two presidents of Colombia. The rebellion finally succeeded in 1819, when the territory of the Viceroyalty of New Granada became the Republic of Greater Colombia, organized as a confederation along with Ecuador and Venezuela (Panama was part of Colombia).

Political Struggle

Internal political and territorial divisions led to the secession of Venezuela and Quito (today’s Ecuador) in 1830. At this time, the name New Granada was adopted, which it kept until 1856 when it became the Grenadine Confederation. After a two-year civil war, in 1863, the United States of Colombia was created, lasting until 1886, when the country finally became known as the Republic of Colombia.

Internal divisions remained, occasionally igniting bloody civil wars, the most significant being the Thousand Days civil war (1899-1902). U.S. intentions to build the Panama Canal led to the separation of Panama in 1903 and its establishment as a separate nation. Colombia was also engulfed in a year-long war with Peru over a territorial dispute involving the Amazonas Department and its capital Leticia.

‘La Violencia’

Soon after Colombia achieved a relative degree of political stability, which was interrupted by a bloody conflict that took place between the late 1940s and the early 1950s, a period known as La Violencia (“The Violence”). Its cause was mounting tensions between the two leading political parties, which ignited after the assassination of the Liberal presidential candidate on April 9, 1948. This assassination caused riots in Bogotá. The violence spread throughout the country and claimed the lives of at least 180,000 Colombians. From 1953 to 1964 the violence between the two political parties decreased, first when Gustavo Rojas deposed the president in a coup d’etat and negotiated with the guerrillas, and then under the military junta of General Gabriel París Gordillo.

The National Front

The two main political parties—the Conservative Party and Liberal Party—agreed to create a coalition government. The presidency would alternate between parties every four years; the parties would have parity in all other elective offices. The National Front ended “La Violencia” and attempted to institute far-reaching social and economic reforms in cooperation with the Alliance for Progress. In the end, the contradictions between each successive Liberal and Conservative administration made the results decidedly mixed. Despite progress in certain sectors, many social and political injustices continued. Guerrilla movements including FARC, ELN, and M-19 were created to fight the government and political apparatus.

Colombian Armed Conflict

During the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s and 1990s, powerful and violent drug cartels emerged, mainly the Medellín Cartel (under the command of Pablo Escobar) and the Cali Cartel, which exerted political, economic, and social influence in Colombia during this period. These cartels also financed and influenced different illegally armed groups across the political spectrum.

To replace the previous 1886 constitution, a new constitution was ratified in 1991 that included key provisions on political, ethnic, human, and gender rights, which have been gradually put in practice, though uneven developments, surrounding controversies, and setbacks have persisted. The new constitution also initially prohibited the extradition of Colombian nationals to the United States. The drug cartels were accused of lobbying in favor of this prohibition and carried out a violent campaign against extradition that included terrorist attacks and mafia-style executions. Drug cartels attempted to influence the government and the political structure of Colombia by means of corruption.

In recent decades, the country has continued to be plagued by the effects of the influential drug trade, guerrilla insurgencies like FARC, and paramilitary groups such as the AUC (later demobilized, though paramilitarism remains active), which, along with other minor factions, have engaged in a bloody internal armed conflict.

Analysts claimed that the drug cartels helped the Colombian trade balance through a steady and substantial influx of foreign currency, mainly U.S. dollars, though other negative economic and social effects also resulted. The drug lords have also destabilized the government.

The different irregular groups often resort to kidnapping and drug smuggling to fund their causes. They tend to operate in the remote rural countryside and can sometimes disrupt communications and travel between regions. Colombia’s most famous hostage, especially internationally, was Ingrid Betancourt, a former senator and presidential candidate known as an outspoken and daring anti-corruption activist. She was kidnapped by FARC in 2002, while campaigning for the presidency and was finally rescued by the government in 2008.

Since the early 1980s, attempts at reaching a negotiated settlement between the government and different rebel groups have been made, either failing or achieving only the partial demobilization of some of the parties involved. One of the latest such attempts was made during the administration of President Andrés Pastrana, which negotiated with the FARC between 1998 and 2002.

In the late 1990s, President Andrés Pastrana implemented an initiative named Plan Colombia, with the dual goal of ending the armed conflict and promoting a strong anti-narcotic strategy. The most controversial element of the Plan, which as implemented also included a smaller number of funds for institutional and alternative development, was considered to be its anti-narcotic strategy, consisting of an increase in aerial fumigations to eradicate coca. This activity came under fire from several sectors, which claimed that fumigation also damaged legal crops and has adverse health effects for populations exposed to the herbicides. Critics of the initiative also claim that the plan represents a military approach to problems that have their roots in the social inequalities of the country, and that it causes coca farmers to clear new fields for crops deeper within jungle areas, significantly increasing the rate of deforestation.

During the presidency of Álvaro Uribe, who was elected on the promise of applying military pressure on the FARC and other criminal groups, some security indicators have improved, such as a decrease in reported kidnappings (from 3,700 in 2000 to 800 in 2005) and a decrease of more than 48 percent in homicides between July 2002 and May 2005. It is argued that these improvements have favored economic growth and tourism.

Uribe, who took office in August 2002, is a staunch U.S. ally whose country was the only one in South America to join the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq. He met President George Bush several times, most recently in May 2007.

Appendix

Notes

- T. Van der Hammen, and G. Correal, Prehistoric Man on the Sabana de Bogota: Data for an Ecological Prehistory, Paleography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology 25 (1978): 179-190.

- Sylvia Broadbent, Los Chibchas: organización socio-política Série Latinoamericana 5 (Bogotá: Facultad de Sociología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 1964).

References

- Academia Colombiana de Historia. Historia extensa de Colombia (41 volúmenes). Bogotá: Ediciones Lerner, 1965-1986.

- Barrios, Luis. Historia de Colombia. Quinta edición, Bogotá: Editorial Cultural, 1984.

- Bedoya F., Víctor A. Historia de Colombia: independencia y república con bases fundamentales en la colonia. Colección La Salle, Bogotá: Librería Stella, 1944.

- Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2001.

- Forero, Manuel José. Historia analítica de Colombia desde los orígenes de la independencia nacional. Segunda edición, Bogotá: Librería Voluntad, 1946.

- Gómez Hoyos, Rafael. La independencia de Colombia. Madrid: Editorial Mapfre, Colecciones Mapfre, 1992.

- Granados, Rafael María. Historia general de Colombia: prehistoria, conquista, colonia, independencia y Repúbica. Octava edición, Bogotá: Imprenta Departamental Antonio Nariño, 1978.

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. Colombia indígena. Medellín: Hola Colina, 1998.

- Restrepo, José Manuel. Historia de la revolución de la República de Colombia. Medellín: Editorial Bedout, 1974.

- Rivadeneira Vargas, Antonio José. Historia constitucional de Colombia 1510-2000. Tercera edición. Tunja: Editorial Bolivariana Internacional, 2002.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia, 09.02.2019, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.