Groups inspired by very early and more modern pushes for civil rights are arming themselves for defense from the radical right.

By Mawa Iqbal

IMPORTANT NOTE (09/18/2025):

Violence has increased across the political divide, and it is important to take note: THIS ARTICLE SIMPLY COVERS THE EXISTENCE OF A PARTICULAR MOVEMENT. BREWMINATE DOES NOT ADVOCATE OR SUPPORT VIOLENCE AGAINST ANY OTHER PERSON OR ANY GOVERNMENT AGENCY IN FURTHERANCE OF ANY IDEOLOGY.

Introduction

On a recent Wednesday evening Renee Maxwell was giving a presentation to about 15 people in front of the Boone County Courthouse in Columbia, Missouri. Soon that crowd doubled, thanks to protestors wrapping up their Black Lives Matter demonstration nearby.

“It was certainly the biggest audience we’ve had since we started doing these kinds of presentations,” Maxwell said.

Maxwell was hosting a “Path to Abolition” workshop, where she discussed ways community members could reallocate funds from local police and invest in other social programs. The talk was followed by a breakout session where attendees discussed specific ways they could reduce their reliance on the police in their everyday lives.

“Ask yourself, ‘Am I in imminent danger, or am I a harm to myself?’ If yes, then call the police,” Maxwell said. “But if no, then you’re better off calling on your neighbors… encouraging folks to talk to their neighbors.”

As the event concluded, attendees began filing out of the amphitheater in front of the courthouse, grabbing 8 to Abolition handouts on their way out. Maxwell was pleased to see some of them sticking around afterwards to ask questions.

“We were definitely seeing a lot more people who are involved with organizing protests having these conversations about police reform,” Maxwell said. “And even those who are not 100% on board with abolition can make more informed decisions about the kind of reform that they want to advocate for.”

Following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in late May, protests against police brutality continue to take place around the world, most recently focused on ongoing stand-offs in Portland, Oregon. In what some call the largest movement in U.S. history, Black Lives Matter has sparked a national debate on what role, if any, law enforcement should play in American society.

“The rest of my comrades are ready to capitalize on this historical moment,” Maxwell said. “These conversations are becoming more mainstream, and our city leadership is already talking about defunding the police, which, you know, a year ago would have been unheard of.”

Armed Liberals

Maxwell and her “comrades” are part of the mid-Missouri chapter of the John Brown Gun Club, an armed, left-leaning social justice group based in Columbia. Much like its namesake abolitionist from the Civil War era, the group advocates for racial equity, among other issues such as the Second Amendment and LGBTQ+ rights.

While it is attracting growing interest from younger activists in the community, groups like the John Brown Gun Club have been advocating for the abolition of police and other forms of systemic injustice since its inception. Unlike most left-leaning groups, though, gun ownership is central to its strategy.

“They view themselves as keeping their right to arm, and to teach and protect others that they see as vulnerable,” said Teal Rothschild, professor of Sociology at Roger Williams University. [Further quote removed]

Rothschild wrote an article last year on the Redneck Revolt, a national network of armed, anti-fascist groups. She noted their “enemy” isn’t the far right, but rather the system.

“Although BLM and other related movements now are largely peaceful, the connections between race relations and guns will continue as long as police violence, disproportionate rates of African Americans being incarcerated, and protests of racial inequality continue,” Rothschild said.

The mid-Missouri chapter of the John Brown Gun Club was founded in August 2017 in response to President Donald Trump’s inauguration, and as part of the Redneck Revolt coalition. The coalition itself was started in 2009, but after a brief hiatus reformed in 2016 by members of community defense groups in Kansas and Colorado.

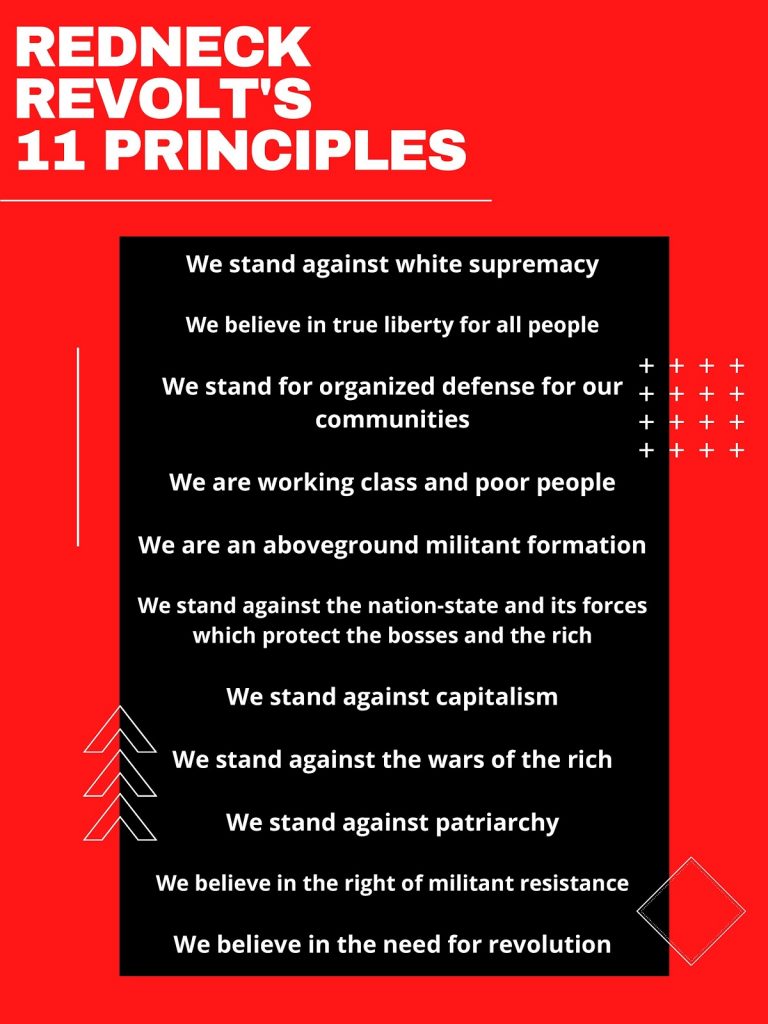

Three years later, Redneck Revolt has dozens of branches all over the country, from Willamette Valley, Oregon to Homestead, Florida. These branches base their ideologies on a set of 11 organizing principles outlined on the Redneck Revolt’s website.

A hallmark of the Redneck Revolt and its branches is the use of firearms to support those principles. Its website includes calls for an armed community defense program in every community, in response to an “upsurge in reactionary and racist violence.”

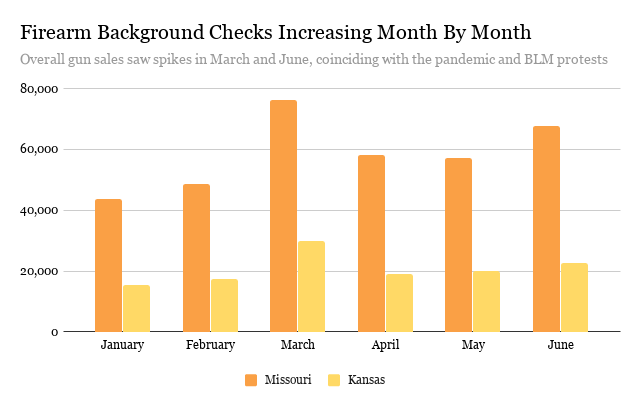

That sentiment may be relevant now more than ever. According to a July report from the Brookings Institution, firearm sales soared at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in mid-March and again in early June amid the George Floyd protests.

During the first six months of the year, an estimated 10 million firearms were sold in this country. About 3.9 million of those firearms were sold in June alone, marking the highest monthly sales total since data collection began in 1998.

“The protests faded but, as public discussions about Black Lives Matter and defunding the police persisted, firearm sales remained elevated throughout the month of June,” the Brookings report said.

Firearms are a big part of the mid-Missouri chapter of the John Brown Gun Club. While most of its projects are centered around advocating for marginalized communities, the club offers community range days at a local conservation area.

Dirk Burhans has been a member of the club for two years. He said the range days are a great way to learn firearm safety in a welcoming, inclusive environment.

“We certainly do train people on how to use firearms, especially women and minorities,” Burhans said. “I think that’s something that I would like to expand into.”

And while the pandemic has interrupted range days for now, Burhans is looking to potentially work with another armed, leftist group in the area on firearm training.

“Within the last year there’s been a new gun club in Columbia called Sharp End,” Burhans said. “They’re a Black gun club, and our group is mostly White, so we hesitate to plow into that territory without being asked. But it’s very much something we want to work toward.”

Shifting Gun Culture

The practice of arming marginalized communities is nothing new. According to Professor Chad Kautzer, the Deacons of Defense and Black Panther movement were both Black civil rights groups from the 1960s who armed themselves.

“I think it’s more pronounced and widespread today, the various kinds of left groups arming themselves,” Kautzer said. “But they are certainly part of a tradition.”

Kautzer is a philosophy professor at Lehigh University, with an emphasis on how race and gender interact with other identities, political and economic structures. He said the recent resurgence of leftist gun groups could be because of a shift in American gun culture.

“The National Rifle Association has transformed from an organization that’s about marksmanship, competition and hunting, into a political organization that’s supposedly about patriotism,” Kautzer said. “This has contributed to a militarizing whiteness over the last several decades, and that’s where we’re at now.”

Kautzer said the emergence of leftist gun clubs is a defensive reaction to a conservative culture that has been arming itself since the 1960s. In his view, that is when American gun culture started to become synonymous with American conservatism.

Law Professor Adam Winkler specializes in gun policy at UCLA, and is the author of “Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms.” He said that trend contradicts what the Second Amendment is all about.

Originally published by Flatland, 07.23.2020, republished under non-indexable fair use for educational, non-commercial purposes.