The Ghaznavids, Seljuks, and Khwarazmians cultivated and expanded Persian culture.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

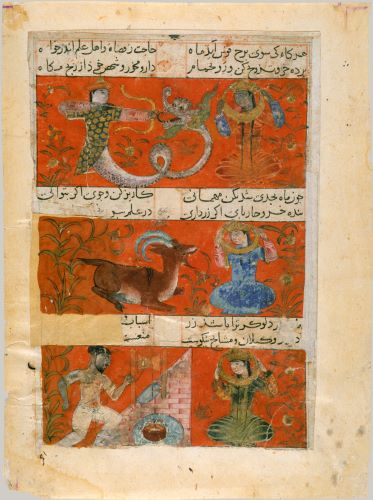

The period from 977 to 1219 witnessed the flourishing of Persianate states and dynasties across the eastern Islamic world, particularly in Iran, Central Asia, and northern India. These polities, while politically diverse and often fragmented, shared a common cultural foundation shaped by the enduring legacy of pre-Islamic Persian traditions and the widespread adoption of the Persian language and courtly norms. The term “Persianate,” as articulated by historians like Marshall Hodgson, denotes a cultural ecumene wherein Persian ideals, administrative practices, and literary forms came to define the elite identity of various dynasties, regardless of their ethnic origins. During this era, the Persianate world was shaped by a series of Turkic and Iranian dynasties that emerged in the vacuum left by the decline of the Abbasid Caliphate’s eastern territories and the fracturing of the Samanid realm. The Ghaznavids, Seljuks, and Khwarazmians were among the most significant of these states, each contributing uniquely to the development and diffusion of Persianate culture.

The Ghaznavid Dynasty: Turkic Swords, Persian Verse, and the Gateway to Empire

The Ghaznavid dynasty, founded by Sebüktegin in 977 and lasting until 1186, marked a pivotal moment in the emergence of Persianate Islamic states ruled by Turkic elites. Though originating as slave-soldiers (ghilman) within the Samanid military structure, the Ghaznavids quickly carved out an independent realm centered in Ghazni, in modern-day Afghanistan. Sebüktegin’s consolidation of power laid the groundwork for his son, Mahmud of Ghazni, who would transform the dynasty into a formidable imperial force. The Ghaznavids demonstrated an adeptness at marrying martial vigor with Persianate cultural legitimacy, adopting Persian as the language of administration and courtly life. They were, in effect, the first major Turkic dynasty to wholly embrace Persian culture, setting a precedent for subsequent rulers across Central and South Asia.1

Mahmud of Ghazni, who reigned from 998 to 1030, exemplified this fusion of martial ambition and cultural patronage. His military exploits—seventeen campaigns into the Indian subcontinent—extended Ghaznavid influence deep into the heart of northern India, establishing tributary relationships and spreading Islamic authority. Yet Mahmud’s legacy is as much cultural as it is military. His court became a beacon of Persianate high culture, drawing poets, theologians, and scientists from across the Islamic world. Most notably, Mahmud patronized the Persian poet Ferdowsi, whose epic Shahnameh provided a literary canonization of Iranian national mythology in a richly Islamicized idiom. Although tensions between Mahmud and Ferdowsi over compensation have become legendary, the ruler’s support for such a work symbolized the centrality of Persian literary heritage to the Ghaznavid conception of kingship.2

The Ghaznavids’ administrative and bureaucratic system was also heavily indebted to earlier Persian traditions. They retained many Samanid institutional frameworks, particularly in their use of Persian-speaking secretaries (dabirs) and viziers who ensured continuity in governance. The dynasty’s political ideology drew upon pre-Islamic Sasanian models of sovereignty, now filtered through Islamic lenses. This synthesis helped secure their legitimacy in the eyes of Persian-speaking elites while reinforcing the dynastic authority of Turkic rulers who lacked direct connection to Arab or Iranian nobility. The Ghaznavid model thus became a prototype for later Turkic dynasties, such as the Seljuks, who likewise adopted Persianate statecraft while maintaining military dominance.3

The Ghaznavids also played a crucial role in the diffusion of Persianate culture into South Asia. As their dominion expanded into the Indian subcontinent, so too did Persian language, art, and administration. Lahore, conquered in the early 11th century, became a key center of Ghaznavid rule and Persianate urban life in the region. The impact of Ghaznavid rule in South Asia endured long after their political decline, as the Indo-Persian cultural synthesis they initiated would become foundational to later Islamic polities in the subcontinent, including the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire. Persian would remain the administrative and literary lingua franca of northern India for centuries, a direct consequence of Ghaznavid policies and presence.4

The decline of the Ghaznavids began in the mid-11th century with the rise of the Seljuks, who defeated them at the Battle of Dandanaqan in 1040. This marked the end of Ghaznavid control over Khurasan and the Iranian plateau, confining them largely to their eastern territories in Afghanistan and the Indian subcontinent. Despite their territorial retreat, the Ghaznavids continued to govern from Lahore until their final overthrow by the Ghurids in 1186. Though politically eclipsed, their cultural legacy proved resilient. The Ghaznavid dynasty’s enthusiastic patronage of Persian literature, its integration of Turkic leadership with Persian administrative forms, and its role in expanding Islam and Persianate norms into India positioned it as a pivotal force in the historical evolution of the Islamic East.5

The Seljuk Empire: Steppes to Scepter in the Persianate World

The Seljuk Empire, founded in the early 11th century by the Oghuz Turkic chieftains Tughril Beg and Chaghri Beg, emerged from the steppes of Central Asia to become one of the most formidable powers of the medieval Islamic world. Their rise began in earnest with the defeat of the Ghaznavids at the Battle of Dandanaqan in 1040, which opened the door for Seljuk expansion across Iran. By 1055, Tughril had entered Baghdad at the invitation of the Abbasid caliph, ostensibly to protect the caliphate from Shi’a Buyid influence. This marked the beginning of a political alliance that would define Sunni Islam for centuries, as the Seljuks became the military and temporal arm of a resurgent Abbasid caliphate. Though Turkic by origin, the Seljuks quickly absorbed Persian administrative and cultural norms, aligning themselves with the Persianate tradition that had become dominant in eastern Islamic lands since the Samanid era.6

Under Alp Arslan and Malik-Shah, the Seljuk Empire reached its zenith, stretching from the Hindu Kush to Anatolia. Alp Arslan’s stunning victory over the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 marked a watershed moment in the history of both the Middle East and Europe. The resulting Seljuk penetration into Anatolia permanently altered the demographic and religious makeup of the region and paved the way for centuries of Turkish presence in what had been a heartland of Eastern Christianity. Yet while their military success was extraordinary, the Seljuks are perhaps most significant for their role in consolidating and institutionalizing the Persianate Islamic state. They preserved and extended the bureaucratic apparatus of earlier dynasties, employed Persian viziers like the renowned Nizam al-Mulk, and endorsed a political ideology that fused Islamic legitimacy with Iranian kingship ideals.7

Nizam al-Mulk, the vizier of both Alp Arslan and Malik-Shah, was instrumental in shaping the intellectual and administrative life of the empire. His treatise, the Siyasatnama (“Book of Government”), provided a manual for statecraft that combined Islamic piety with pragmatic governance rooted in Persian courtly traditions. He also established the Nizamiyya system of madrasas—state-sponsored religious colleges aimed at cultivating Sunni orthodoxy and administrative loyalty. These institutions were vital in countering the influence of Shi’a movements, such as the Fatimids and Ismailis, and in forging a new class of bureaucrats, jurists, and scholars loyal to the Sunni Seljuk state. The Seljuks thereby helped to institutionalize Sunni Islam in ways that would endure well beyond their political collapse, ensuring a legacy not only of military conquest but also of religious and cultural consolidation.8

The Seljuk embrace of Persianate culture extended into the realm of literature, architecture, and science. Persian remained the language of administration and high culture throughout the empire, and poets, historians, and philosophers flourished under their patronage. Cities like Nishapur, Rayy, Isfahan, and Baghdad became vibrant intellectual centers where Islamic jurisprudence, theology, and natural philosophy advanced alongside Persian literary production. The polymath Omar Khayyam, known in the West for his quatrains, was commissioned to reform the calendar by Malik-Shah and exemplifies the blending of Persian intellectual heritage with Islamic inquiry that defined the Seljuk age. Architecturally, the Seljuks introduced innovations in mosque construction, madrasas, and caravanserais, laying the stylistic foundations for later Islamic architecture in both the Iranian plateau and Anatolia.9

Despite their cultural and institutional achievements, the Seljuk Empire began to fragment after the death of Malik-Shah in 1092. Succession disputes, regional rivalries, and the assertiveness of atabegs (governors of provinces who became de facto rulers) gradually eroded central authority. By the early 12th century, the once-unified empire had splintered into smaller states, including the Sultanate of Rum in Anatolia and various semi-autonomous emirates in Iran and Iraq. Nevertheless, the Seljuk legacy endured in multiple forms. They had solidified Persianate Islam as the political and cultural norm across a vast swath of the Islamic world. Their innovations in educational institutions, administrative practice, and ideological articulation of Sunni kingship shaped subsequent dynasties, from the Zengids and Ayyubids to the Mamluks and Ottomans. The Seljuk Empire thus stands as a cornerstone of Islamic civilization, bridging the nomadic steppe traditions of Turkic peoples with the urban and literary heritage of Iran.10

The Khwarazmian Empire: Last Light of Persia before the Mongol Storm

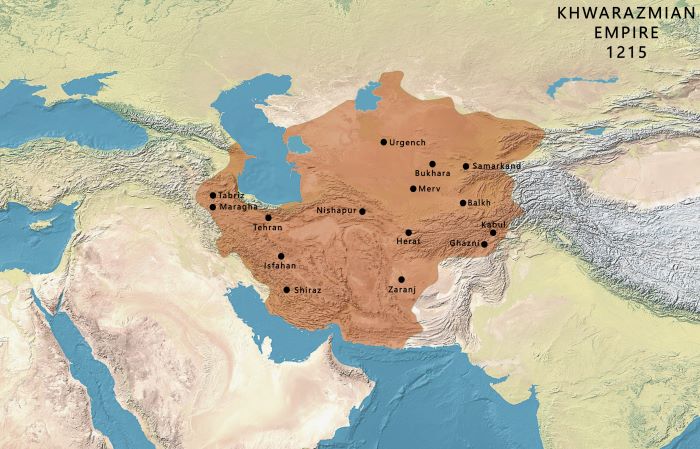

The Khwarazmian Empire, which rose to prominence in the 12th century and reached its zenith in the early 13th, was the final great Persianate state to emerge before the Mongol storm obliterated the political landscape of the Islamic East. Initially established as vassals of the Seljuks in the province of Khwarazm—an ancient region situated along the Amu Darya in modern-day Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan—the Khwarazmshahs steadily expanded their autonomy and territorial ambitions. By the time of Ala al-Din Tekish (r. 1172–1200), the dynasty had severed formal Seljuk ties and assumed a posture of imperial sovereignty, adopting the trappings of Persian kingship while maintaining a fiercely militarized state apparatus rooted in their Turkic heritage. Like the Ghaznavids and Seljuks before them, the Khwarazmshahs ruled as Turkic princes within a profoundly Persianate cultural framework, a duality that typified Islamic governance in the region after the decline of Arab political power.11

The empire’s apogee came under Tekish’s son, Ala al-Din Muhammad II (r. 1200–1220), who forged an empire stretching from the fringes of India to the Caucasus, and from the Persian Gulf to the Syr Darya. His reign marked the culmination of a century-long effort to assert Khwarazmian independence and supremacy over former Seljuk territories, including the absorption of Ghurid lands and parts of western Iran. Though the Khwarazmian court was ethnically Turkic, it was thoroughly Persian in its bureaucracy, language, and literary patronage. Persian was the language of administration, poetry, and historiography, and the court’s patronage extended to scholars and theologians who contributed to the broader flowering of Islamic civilization in the pre-Mongol period. The Khwarazmshahs claimed the legacy of ancient Iranian monarchy, styling themselves in a Sasanian idiom and asserting themselves as rightful heirs to both Islamic and Persian imperial tradition.12

Yet even at the height of its power, the Khwarazmian Empire was undermined by internal weaknesses and strategic overreach. Ala al-Din Muhammad’s reign was marked by growing tensions between the center and periphery, fractious relations with subject populations, and an increasingly autocratic style of governance. His growing estrangement from the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad—whom he sought to depose and replace—further alienated religious elites, while his heavy-handed policies in newly annexed territories fostered discontent. The Khwarazmshah’s failure to consolidate his vast conquests into a stable and coherent polity rendered the empire brittle beneath its impressive exterior. Nevertheless, it was not internal discord alone that would doom the Khwarazmians; it was their fateful miscalculation in confronting a force still in its adolescence: the Mongols.13

The encounter with Genghis Khan’s Mongol Empire proved catastrophic and terminal. In 1218, the execution of a Mongol trade delegation by Khwarazmian officials—a decision sanctioned or at least tolerated by Muhammad—was met with the wrath of one of history’s most ruthless conquerors. Genghis Khan’s ensuing invasion, launched in 1219, was not a punitive expedition but a campaign of annihilation. Cities that had flourished for centuries—Samarkand, Bukhara, Nishapur, Merv—were reduced to smoldering ruins, their populations slaughtered or enslaved. The Khwarazmian military, formidable though it was, proved no match for the discipline, speed, and terror tactics of the Mongol war machine. Ala al-Din Muhammad died in flight on an island in the Caspian Sea in 1220, leaving the remnants of his empire to his son Jalal al-Din, whose valiant but doomed resistance would provide only a brief epilogue to the story of Khwarazmian glory.14

Despite its sudden and violent end, the Khwarazmian Empire left an imprint on the historical and cultural landscape of the Persianate world. It represented the final flowering of the eastern Islamic monarchy in its classical form—a Turkic dynasty wielding Persianate ideology, language, and aesthetics in service of Islamic imperial ambition. Its demise at the hands of the Mongols marked not only the fall of a dynasty but the end of an era in which indigenous Islamic polities dominated the Iranian plateau and Central Asia. The Mongols would adopt many aspects of the Persianate model they had destroyed, particularly under the Ilkhanids, but they ruled as outsiders—initially ambivalent toward Islam, later converts by necessity. In this light, the Khwarazmian Empire stands as both culmination and elegy: the last native empire of the pre-Mongol Persian world, incandescent in its rise, tragic in its fall, and foundational in its legacy.15

Conclusion

The period between 977 and 1219 represents both a high point and a turning point in the evolution of Persianate civilization. During these centuries, the Persian language replaced Arabic as the dominant medium of elite literary and bureaucratic expression in much of the Islamic East. Courtly life, statecraft, architecture, and historical memory were all shaped by Persian norms, creating a transregional cultural identity that transcended ethnic and sectarian divisions. The Turkic-led empires of this era—Ghaznavid, Seljuk, and Khwarazmian—did not merely adopt Persian culture; they actively cultivated and expanded it, leaving an enduring legacy that would shape the Islamic world from Anatolia to India for centuries to come.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Clifford Edmund, The Ghaznavids: Their Empire in Afghanistan and Eastern Iran 994–1040 (Beirut: Librairie du Liban, 1963), 17–22.

- Dick Davis, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings (New York: Penguin Classics, 2006), xii–xvii.

- Edmund Herzig and Sarah Stewart, eds., Early Islamic Iran (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 145–148.

- Muzaffar Alam, The Languages of Political Islam in India: 1200–1800 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 14–16.

- Clifford Edmund Bosworth, “The Later Ghaznavids,” in The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, ed. J. A. Boyle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 66–71.

- A. C. S. Peacock, The Great Seljuk Empire (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), 47–52.

- Carole Hillenbrand, Turkish Myth and Muslim Symbol: The Battle of Manzikert (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 103–107.

- Nizam al-Mulk, The Book of Government or Rules for Kings: The Siyasatnama, trans. Hubert Darke (London: Routledge, 2002), x–xvii.

- Richard W. Bulliet, The Patricians of Nishapur: A Study in Medieval Islamic Social History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972), 23–27.

- Clifford Edmund Bosworth, “The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217),” in The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, ed. J. A. Boyle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 26–34.

- Clifford Edmund Bosworth, The History of the Saffarids of Sistan and the Maliks of Nimruz (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1994), 165–170.

- Peter B. Golden, Central Asia in World History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 93–96.

- Michal Biran, The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 173–176.

- Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 15–20.

- David Morgan, The Mongols (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 46–52.

Bibliography

- Alam, Muzaffar. The Languages of Political Islam in India: 1200–1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Allsen, Thomas T. Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Biran, Michal. The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Bosworth, Ciifford Edmund. The Ghaznavids: Their Empire in Afghanistan and Eastern Iran 994–1040. Beirut: Librairie du Liban, 1963.

- —-. The History of the Saffarids of Sistan and the Maliks of Nimruz. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1994.

- —-. “The Later Ghaznavids.” In The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 5, The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, edited by J. A. Boyle, 66–71. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968.

- —-. “The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217).” In The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 5, The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, edited by J. A. Boyle, 1–202. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968.

- Bulliet, Richard W. The Patricians of Nishapur: A Study in Medieval Islamic Social History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

- Davis, Dick, trans. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. New York: Penguin Classics, 2006.

- Golden, Peter B. Central Asia in World History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Herzig, Edmund, and Sarah Stewart, eds. Early Islamic Iran. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

- Hillenbrand, Carole. Turkish Myth and Muslim Symbol: The Battle of Manzikert. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

- Morgan, David. The Mongols. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

- Nizam al-Mulk. The Book of Government or Rules for Kings: The Siyasatnama. Translated by Hubert Darke. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Peacock, A. C. S. The Great Seljuk Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.