There is reason to be optimistic about the potential for effectively correcting misperceptions, particularly among people who are genuinely open to the facts.

Dr. Brendan Nyhan

Assistant Professor, Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy

University of Michigan

Dr. Jason Reifler

Assistant Professor of Political Science

Georgia State University

Summary

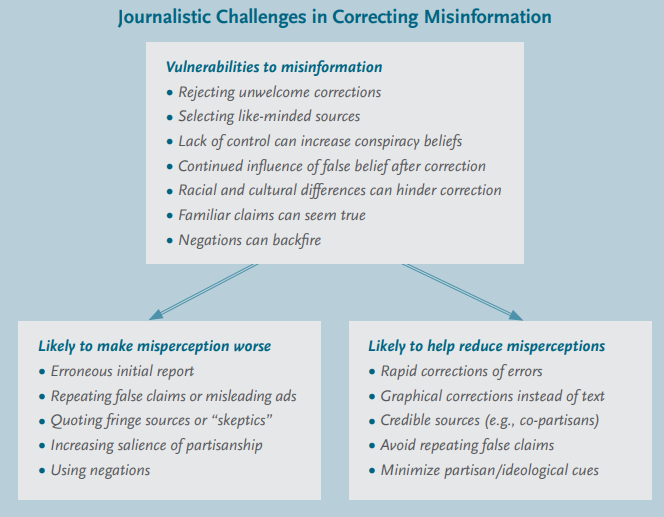

Citizens and journalists are concerned about the prevalence of misinformation in contemporary politics, which may pollute democratic discourse and undermine citizens’ ability to cast informed votes and participate meaningfully in public debate. Academic research in this area paints a pessimistic picture—the most salient misperceptions are widely held, easily spread, and difficult to correct. Corrections can fail due to factors including motivated reasoning, limitations of memory and cognition, and identity factors such as race and ethnicity.

Nonetheless, there is reason to be optimistic about the potential for effectively correcting misperceptions, particularly among people who are genuinely open to the facts. In this report, we offer a series of practical recommendations for journalists, civic educators, and others who hope to reduce misperceptions:

- Get the story right the first time.

- Early corrections are better.

- Beware making the problem worse. to the fringe.

- Avoid negations.

- Minimize repetition of false claims.

- Reduce partisan and ideological cues.

- Use credible sources; don’t give credence .

- Use graphics where appropriate.

- Beware selective exposure.

These recommendations consider several possible approaches journalists can take to protect citizens who are targeted with misinformation. First, they can try to push citizens out of the line of fire by, for instance, getting the story right the first time, refusing to give credence to fringe sources, and minimizing repetition of false claims. In this way, people are less likely to be taken in by misinformation. Second, reporters can try to repair the damage inflicted by false information by correcting it after the fact as quickly as possible, avoiding the use of negations in corrections, reducing partisan and ideological cues in stories intended to reduce misinformation, and using graphics when appropriate in correcting mistaken beliefs. Ideally, however, we would like to shield citizens with the misinformation equivalent of a bulletproof vest. This report has mainly identified techniques that could help to limit the damage of misinformation. In order to push citizens out of the way of misinformation or shield them from its effects, more research is needed about, for instance, the reasons why people sometimes reject corrections, the influence of media sources on the effectiveness of corrective information, and the consequences of people avoiding counterattitudinal corrections.

Moreover, if fact-checking is not always able to repair the damage caused by misinformation, its very existence may still help to reduce the misinformation that is directed at the American people. The existence of media watchdogs and fact-checkers may reduce the incentives for political elites to promote misleading claims. In this way, fact-checking can both increase the reputational costs of creating misinformation and limit its dissemination. These effects can be especially powerful when fact-checkers create an elite consensus that crosses partisan and ideological lines.

Summary of Social Science Findings

Information deficits: Factual information can change policy preferences, but the effect is not consistent. Information seems to be most effective in shaping preferences about government spending. One drawback to these studies is that they generally do not directly measure changes in misperceptions.

Motivated reasoning: People’s evaluations of new information are shaped by their beliefs. Misperceptions seem to generally reflect sincere beliefs. Information that challenges these beliefs is generally unwelcome and can prompt a variety of compensatory responses. As a result, corrections are sometimes ineffective and can even backfire.

Ad watches: Studies examining campaign ad watch stories reached conflicting conclusions about the effectiveness of these segments.

Belief perseverance and continued influence: Once a piece of information is encoded in memory, it can be very difficult to eliminate its effects on subsequent attitudes and beliefs.

Sources matter: The source of a given statement can have a significant effect on how the claim is interpreted. People are more receptive to sources that share their party affiliation or values and those that provide unexpected information.

Negations, affirmations, and fluency: Attempts to correct false claims can backfire via two related mechanisms. First, repeating a false claim with a negation (e.g., “John is not a criminal”) leads people to more easily remember the core of the sentence (“John is a criminal”). Second, people may use the familiarity of a claim as a heuristic for its accuracy. If the correction makes a claim seem more familiar, the claim may be more likely to be seen as true.

Identity and race: When information about race or social identity is salient, it can undermine the effectiveness of corrections about public figures from different racial or cultural backgrounds.

Threats to control: When people feel a lack of control, they compensate with strategies that lead to greater acceptance of misperceptions.

Visuals: Graphics may be an effective way to present corrective information about quantitative variables. However, graphical representations of the accuracy of political statements were found to have no effect on factual knowledge.

Introduction

Journalistic watchdogs can help to change elite incentives to promote misleading claims and can inform journalists who would otherwise disseminate those claims. In this way, fact-checking may help to increase the reputational costs of misinformation and limit its dissemination even when individual-level misperceptions are difficult to correct. More importantly, fact-checking can have especially powerful effects when it helps create an elite consensus that crosses partisan or ideological lines.

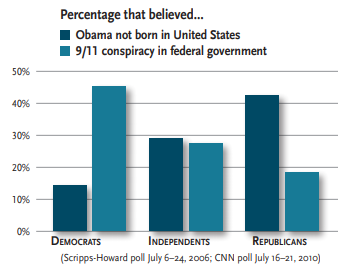

Citizens and journalists alike are concerned about the prevalence of misinformation in contemporary politics, which may pollute democratic discourse and undermine citizens’ ability to cast informed votes and participate meaningfully in public debate. In recent years, for example, we have seen widespread belief in outlandish claims that the Bush administration intentionally allowed or assisted the 9/11 terrorist attacks (especially among Democrats)[1] and that President Obama was not born in this country (especially among Republicans).[2] Other misperceptions focus on policy—for instance, the amount the U.S. spends on foreign aid,[3] the performance of the economy under presidents from the other party,[4] or the effects of tax cuts on government revenue.[5] Many of these myths have proven to be remarkably difficult to correct.

To date, most academic research on political knowledge has focused on documenting that Americans are uninformed about policy and politics.[6] Far less is known about whether and to what extent people are misinformed and how they can be persuaded to change their minds. The challenge for social scientists going forward is to learn more about how people come to hold misperceptions and to determine the most effective way to counter these mistaken beliefs. This research brief summarizes the most relevant findings from the growing academic literature on misperceptions, identifies best practices and approaches to avoid in correcting misinformation, and highlights areas where further study is needed.

We first briefly discuss the characteristics of misperceptions, which often concern well-known political figures like Sarah Palin and Barack Obama and controversial issues such as the war in Iraq, immigration, and taxes. They can be created by politicians and interest groups or can emerge from the grassroots and then circulate via elite statements, media coverage, and/or social networks. At the individual level, misperceptions are often disproportionately held by members of one of the two major parties, especially on salient issues that are widely covered in the press. People who are more educated or knowledgeable tend to have more accurate beliefs, but this relationship is surprisingly inconsistent.

We then review individual-level experimental research from political science, psychology, and communications that provides insight into misperceptions and how best to counter them. Overall, academic research in this area paints a pessimistic picture—the most salient misperceptions are widely held, easily spread, and difficult to correct. Studies show how corrections can fail due to factors including motivated reasoning, limitations of human memory and cognition, and social identity factors such as race and ethnicity. Nonetheless, there is reason for cautious optimism. We identify several strategies that show at least some promise in experimental studies, including using credible or unexpected sources, avoiding negations, and presenting quantitative information in graphical form. Based on these findings, we offer a series of practical recommendations for journalists and educators who hope to reduce misperceptions and identify areas where further research is needed. We then conclude by discussing how fact-checking might be most effective at the elite level. Journalistic watchdogs can help to change elite incentives to promote misleading claims and can inform journalists who would otherwise disseminate those claims. In this way, fact-checking may help to increase the reputational costs of misinformation and limit its dissemination even when individual-level misperceptions are difficult to correct. More importantly, as we note, fact-checking can have especially powerful effects when it helps create an elite consensus that crosses partisan or ideological lines.

A Primer on Misperceptions

There is widespread evidence that Americans hold numerous political misperceptions, which we define as beliefs about policy or politics that are factually incorrect or contrary to the best available evidence.[7 These false or unsupported beliefs range from myths about political figures to false beliefs about policy issues.

First, misperceptions about political candidates and government officials are perhaps the most widely covered by the media. Most recently, President Obama has been plagued by false beliefs that he is a Muslim and that he was born outside the United States. Similarly, after John McCain selected Alaska governor Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008, false Internet rumors began circulating that Palin had not given birth to her son Trig.[8]

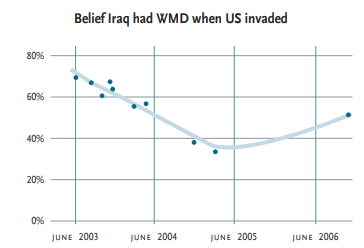

If misperceptions were limited to candidates, perhaps they could be overlooked as an unhappy consequence of political campaigns. Unfortunately, misperceptions about controversial political issues like the economy, immigration, and taxes are also common. For example, surveys have shown that many Americans believe that the U.S. found weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in Iraq.[9] Similarly, Americans overestimate the number of illegal immigrants in the U.S. or their state,[10] the proportion of the population making over $250,000 a year,[11] and the percentage of people who are subject to the estate tax.[12] Public support for these beliefs does not always respond to available evidence.

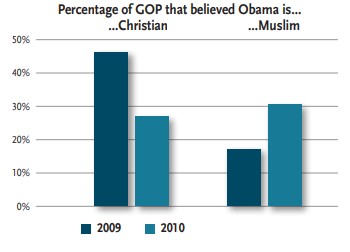

The graphics above provide two examples. First, in 2006, long after the Duelfer Report concluded that Iraq did not have WMD before the U.S. invasion, the belief that Iraq did have WMD appeared to increase according to Harris poll data from the 2003- 2006 period. Likewise, Republican beliefs that President Obama is a Muslim increased between 2009 and 2010 even though no evidence had emerged to support the claim.[13]

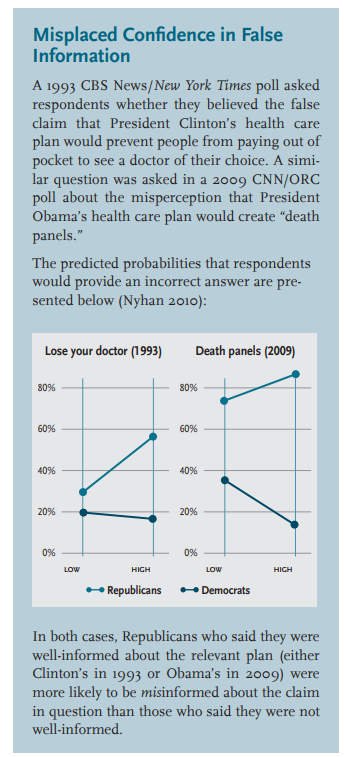

Myths and misconceptions seem to be especially pervasive on the topic of health care, a sensitive issue that often has high personal or partisan stakes. For example, during the recent debates over health care reform legislation, many people came to believe that the Obama plan encouraged euthanasia for senior citizens. One of us (Nyhan) found that this misperception paralleled those that surrounded the Clinton health care plan in 1993-1994.[14] In both cases, Republicans who believed they were more informed about the plan in question were actually more likely to be misinformed (see sidebar on the next page).

Surveys also show that alarming proportions of Americans believe that vaccines are dangerous—a misperception that may have been fueled by the publication in The Lancet of a since-discredited and retracted study linking autism to the Measles-MumpsRubella (MMR) vaccine.[15] Such misperceptions were likely strengthened by presidential candidate Michele Bachmann’s recent comments suggesting that the HPV vaccine caused mental retardation.[16]

Finally, these myths also vary by their source. Many, of course, are created by politicians. For example, in an August 2009 post on Facebook, Sarah Palin invented the myth that President Obama’s health care reform plan would create “death panels.”[17] Myths can also come from interest groups. The third-party group Swift Boat Veterans for Truth ran television ads making unsupported claims about Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry’s record in Vietnam that were widely disseminated during the 2004 campaign.[18] Some myths bubble up from the grassroots with little elite support. For instance, the claims of a Bush administration conspiracy to allow the 9/11 attacks received virtually no support from Democrats other than Rep. Cynthia McKinney[19] and Vermont governor Howard Dean.[20] Of course, prominent rumors and misinformation can also spread rapidly via social network mechanisms such as email[21] as well as elite statements and news coverage.[22] For example, less than two weeks after Palin’s Facebook post, 86% of Americans had heard of her claim that Obama’s health care plan would create “death panels.”[23]

At the individual level, the prevalence of particular misperceptions often varies dramatically depending on partisanship or ideology, particularly for the most salient or controversial misperceptions. For example, more than half of self-identified strong Democrats surveyed in a 1988 poll incorrectly believed that inflation worsened during Ronald Reagan’s presidency compared with only 13% of strong Republicans.[24] In surveys conducted during 2006, 2009, and 2010, Democrats were also much more likely to say that the Bush administration allowed the terrorist attacks of 9/11.[25] Similarly, surveys continue to find that Republicans are much more likely to say that Obama is a Muslim[26] or that he was born outside the U.S.[27] The graphic below contrasts two of these polls to illustrate the role of partisanship in misperceptions.

Conversely, ambivalent partisans (i.e., those who express some negative views of their own party or positive views about the other party) have been shown to have more accurate perceptions of economic conditions and positions taken by elected officials than citizens who are not ambivalent. These data suggest that respondents with less motivation to engage in selective exposure or interpretation are less likely to be misinformed.[28]

Partisan differentials in misperceptions are also likely to vary depending on the media coverage given to a particular issue. A study of more than 200 survey questions administered over more than two decades finds that partisans are more likely to provide correct answers to factual issue questions that are favorable to their party than to questions with negative implications. This partisan gap in factual knowledge widens on issues that receive extensive news coverage.[29] In particular, increased media coverage of an issue fails to increase accuracy among partisans when the question has negative implications for their party. One reason may be increased exposure to misinformation through media coverage. For example, respondents surveyed when misleading claims about Social Security were in the news were more likely to be misinformed about the program’s solvency.[30]

Finally, people who are more politically knowledgeable tend to have more accurate factual beliefs about politics. However, people who are more knowledgeable are also more likely to seek out information that is consistent with their beliefs and to reject claims that conflict with their own ideas.[31] As a result, the relationship between knowledge and misperceptions is often weak or inconsistent. For instance, George Washington University political scientist John Sides found that belief in the false claim that President Obama is Muslim increased more between March 2009 and August 2010 among Republicans who had some college or had graduated from college (a proxy for political knowledge) than among those who had not gone to college.[32] Similarly, Yale Law School professor Dan Kahan and his colleagues found that scientific literacy and numeracy were not strong predictors of believing that climate change poses a serious risk to humans. Instead, respondents who were more scientifically literate and numerate were more polarized based on their cultural values than those with lower levels of scientific literacy and numeracy.[33]

Research Findings and Approaches

In this section, we summarize the academic research on misperceptions and attempts to correct them. We organize our review based on the theoretical approaches scholars use to study misperceptions. However, it is important to point out that even studies conducted by scholars working within the same theoretical framework can differ in important ways. In particular, some studies seek to identify how corrective interventions change factual beliefs, whereas others are focused on the change in policy opinions resulting from corrections. We distinguish between these different outcomes as necessary.

Information deficits: More facts aren’t always better

Studies that examine information deficits often start with the premise that people lack crucial facts about a relevant issue. Using experiments, scholars estimate the effects of providing factual information on respondents’ policy preferences by comparing the opinions of participants who were randomly given factual information with the opinions of those who were not. In many cases, scholars working in this approach assume people are uninformed rather than misinformed and do not differentiate among respondents based on their prior beliefs about the claim or issue in question.

One of the more optimistic studies in the field found that giving policy-specific information to survey respondents affected their policy preferences in understandable ways.[34] Specifically, telling participants in a 1998 survey experiment that the crime rate “is now lower than at any time since 1974” resulted in less support for increased federal spending on prisons. Similarly, telling participants that “the amount of money we spend on foreign aid has been going down and now makes up less than one cent of every dollar that the federal government spends” resulted in increased support for federal spending on foreign aid. Likewise, giving study participants information about how few American pay the estate tax (about 1%) was found to increase support for the tax,[35] while providing information about education spending and teacher salaries decreased support for more spending on education in general and teacher salaries in particular.[36] Lastly, a 2008 study found that informing people that the home mortgage deduction primarily benefits the most affluent Americans reduced support for the program among low and middle income people.[37]

However, not all interventions designed to address information deficits have been shown to alter preferences. For instance, a late 1990s telephone survey experiment by University of Illinois political scientists found that individuals who were least informed about federal welfare programs were the most confident in the accuracy of their factual beliefs.[38] As such, it was disappointing—but not surprising— that providing respondents with corrective information did not change their opinions about welfare policy. A followup experiment with undergraduates used a more dramatic (though arguably unrealistic) intervention to provoke a response—immediately after some respondents gave an estimate of the proportion of federal spending devoted to welfare (which they tended to overestimate), they were told the correct value. This correction did reduce participants’ support for cutting welfare. Similar studies have found that giving people information about the actual number of illegal immigrants in the U.S. did not alter immigration attitudes (even though people frequently overestimate the size of the illegal immigration population)[39] and that providing information about the human or financial costs of the Iraq war did little to alter judgments about whether the war was worth fighting.[40]

Taken as a whole, these studies show that people’s policy opinions can sometimes be responsive to new information. However, there are some important limitations. First, the effects of factual information on policy opinion are not consistent. Perhaps the Iraq war and immigration were sufficiently salient that most respondents’ policy attitudes were crystallized at the times the studies were conducted, thus diminishing the opportunity for corrective information to affect preferences. Alternatively, perhaps there is something about the nature of spending opinions that makes it easier for people to adjust their preferences in response to new information. Second, these studies generally do not differentiate between respondents based on their prior knowledge or political views. It would be worthwhile to examine how opinions changed among respondents who were previously misinformed or among those who might be especially predisposed toward inaccurate beliefs for ideological or partisan reasons.

Summary: Factual information can change policy preferences, but the effect is not consistent. Information seems to be most effective in shaping preferences about government spending. One drawback to these studies is that they generally do not directly measure misperceptions, making it difficult to determine whether underlying factual beliefs change in response to corrective information.

Motivated reasoning: The influence of people’s opinions on their factual beliefs

To understand how people form and maintain misperceptions, it is especially useful to draw from social psychology and political science research on motivated reasoning.[41] First, experimental evidence suggests that people seek out information that is consistent with their pre-existing views and avoid information that contradicts their prior beliefs, a phenomenon known as selective exposure.[42] Though both tendencies are likely to exist, this effect may be stronger for attitudinally congruent information.[43] When processing information, people are similarly prone to accepting claims that reinforce their preexisting views (confirmation bias) while rejecting or ignoring statements that undermine their beliefs or opinions (disconfirmation bias).[44] In this way, individuals may be more likely to be exposed to false or unsupported information that conforms with their pre-existing views and to accept such information as true when exposed to it. Conversely, people may be less likely to come into contact with corrective information and to reject it when they do so. These biases are likely to be stronger among politically sophisticated individuals and among those with stronger attitudes on the issues in question.[45] (Conversely, these effects will be weaker among individuals who are less politically sophisticated and among those with weak attitudes.) There is also an ongoing debate about whether motivated reasoning is stronger among conservatives than liberals.[46]

The process by which people resist accepting counterattitudinal information can take several different forms (which often appear in combination). These resistance processes can include counterarguing (attempting to directly rebut the claim in question), attitude bolstering (bringing to mind reasons that the initial belief was correct), source derogation (dismissing the validity of the source of the claim), negative affect (becoming upset or angry), message distortion (selectively interpreting the claim to preserve a prior belief), social validation (bringing to mind others who hold the same view), and selective exposure (ignoring or avoiding the information entirely).[47] Classic examples of these responses include the hostile media effect, which shows that both sides of a dispute often view news reports as being biased against them,[48] and studies showing that people interpret scientific evidence as more persuasive when it is consistent with their opinions.[49]

Unlike the information deficit studies described above, scholars working in the motivated reasoning framework are more likely to consider how respondents’ pre-existing views affect their reactions to corrective information. As such, these studies more frequently highlight the ways in which disconfirmation bias hinders corrections from being effective.

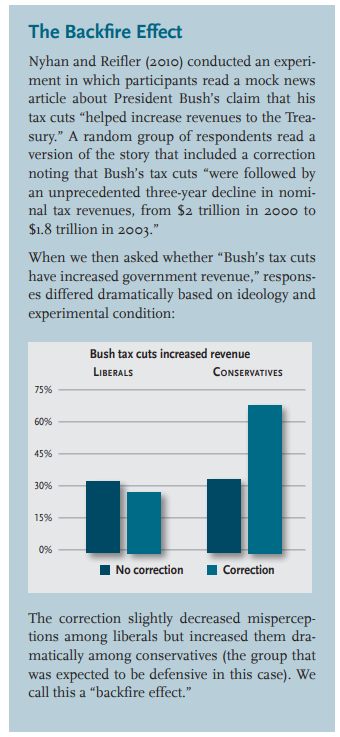

For example, we (Nyhan and Reifler) conducted experiments with undergraduates in 2005 and 2006 that looked more specifically at how responses to corrections vary depending on people’s point of view. Our studies found that realistic corrections embedded in mock news articles were frequently ineffective at reducing misperceptions among the ideological group most likely to hold the misperception (e.g., liberals or conservatives). In some cases, corrections actually made misperceptions worse among the targeted group—a phenomenon we call a “backfire effect.”[50] The sidebar above provides a sample of our methodology and results.

Unlike our previous studies, a survey experiment conducted by MIT’s Adam Berinsky in 2010 found that Democrats and Republicans responded similarly to a correction of the euthanasia rumor, which was relatively successful at reducing misperceptions among both groups. However, a subsequent experiment found that the correction was more effective when administered without repeating the rumor. Unlike the first study, the correction had little effect on Republicans who were also exposed to the rumor as part of the experiment.[51]

The persistence of political misperceptions may be the result of the threat to respondents’ self-concept or worldview posed by unwelcome corrective information. In experiments conducted in 2008 and 2011, we tested an intervention intended to buffer this threat and thereby make respondents more open-minded.[52] This exercise, which is called self-affirmation, asks respondents to write a few sentences about a time in which they upheld a value that is important to them. We (Nyhan and Reifler) found that going through this process reduced reported misperceptions among the political subgroups most likely to hold them. For instance, supporters of withdrawing from Iraq who were affirmed were more likely to state that attacks had declined after the U.S. troop surge there. This result suggests that acknowledging uncomfortable facts is difficult for respondents in the absence of a self-affirmation exercise.

A different interpretation is that the high levels of reported misperceptions in the surveys and experiments reported above may reflect partisan cheerleading rather than sincere expressions of factual beliefs. Three Yale political scientists conducted experiments testing this hypothesis in which they offered financial incentives for correct answers to questions that members of one party would be more likely to answer incorrectly.[53] The incentives were found to have relatively small effects. Even among participants who were paid $2 per correct answer (the maximum offered), the gap in knowledge between parties was only reduced by 40%. These results suggest that partisan differences in factual knowledge and misperceptions are largely sincere. Alternatively, these financial incentives may not have been sufficiently lucrative to induce partisans to acknowledge threatening facts.

Summary: People’s evaluations of new information are shaped by their beliefs. Information that challenges beliefs that people hold strongly is generally unwelcome and can prompt a variety of compensatory responses. (By contrast, individuals will be much more likely to accept corrective information if they are not motivated to defend a mistaken belief.) These mechanisms can explain why corrections are sometimes ineffective and can even make misperceptions worse in some cases. The available evidence suggests that misperceptions generally reflect sincere differences of belief and are fueled in part by the threat to self that is induced by counterattitudinal information.

Ad watches: The debate over their effectiveness

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, concerns were raised that critical news coverage that replayed misleading political ads ended up reinforcing the messages of the ads. For example, a 1992 study testing two ad watches found that one was effective in making attitudes toward a targeted advertisement more negative, but the other made viewers’ attitudes toward the ad in question more positive.[54]

As a result of these sorts of concerns, CNN developed a new rubric for ad watches based on proposals developed by University of Pennsylvania communications professor Kathleen Hall Jamieson.[55] These segments played the ad in a box to reduce its effects and interrupted the ad to critique its claims. In experiments conducted in 1992, Jamieson and a colleague found that people exposed to ad watches presented in this style were less likely to view the ad in question as fair, though the effects of the ad watch on viewers’ ability to recall the content and motivation of the ad were mixed.[56] A subsequent study by other scholars[57] found similar results using newspaper ad watch articles—participants liked candidates less when their ads were disconfirmed—while another study found that video ad watches were effective at countering ads focused on the candidate’s image, though not those focused on policy issues.[58]

In contrast to these findings, a study by two political scientists found that campaign ad watch segments aired on CNN during the 1992 campaign actually made participants more likely to support the candidate whose ad was being criticized.[59] The authors attributed this finding to ad watches repeating the ad and reinforcing the messages in the ad (e.g., a Clinton ad emphasizing Bush as out of touch by showing his positive statements about the economy when the public was far more dour). In a response, Jamieson and a colleague countered by noting that the ad watches used in the study described the candidate ads being fact-checked as (mostly) accurate.[60] For example, the critique by Brooks Jackson of CNN of one Bush ad was “[n]othing really false here…but the Bush ad does take some liberties.” The critique of a Clinton ad was “[t]he Clinton ad sticks to the facts but picks those facts carefully. No false advertising, but no Arkansas miracle.” The implications of these findings are therefore less clear. If the expectation is that campaigns should be punished for lying, then they might also be rewarded for truth-telling.

Summary: Studies examining campaign ad watch stories in television and print reached conflicting conclusions about the effectiveness of these segments.

Belief perseverance and continued influence: Misinformation can have a lasting effect

The above discussion of motivated reasoning examines how people employ cognitive effort to resist corrective information. However, even if people are not actively engaged in resisting unwelcome facts, the limitations of memory can also hinder the correction of misperceptions through phenomena known as belief perseverance and the continued influence effect.

In the canonical studies of belief perseverance,[61] participants were given a novel task—discriminating between real and fake suicide notes. However, subjects were not given accurate feedback on their performance but instead were randomly told they were above or below average at the task. Even though subjects were later told that the feedback was random, participants who were told they were above average thought they would perform much better at the task in the future than those who were told they were below average.

Recent research in political science has found that belief perseverance occurs in politics, but sometimes differs by partisanship. In three different experiments, each of which takes the basic form of reporting a news event with an error and then offering a correction, Yale political scientist John Bullock finds that belief perseverance differs substantially across partisan subgroups.[62] People who are members of the opposite party from the target of the false claim continue to be affected by negative information even after it is corrected (e.g., Democrats who are told a false claim about Supreme Court nominee John Roberts), whereas members of the target’s party show no lingering negative effects after a correction (e.g., Republicans who heard the Roberts claim).

Similarly, in a paper written with North Carolina State political scientist Michael Cobb, we show that there are asymmetries in belief perseverance for positive and negative information.[63] Specifically, Cobb, Nyhan, and Reifler find belief perseverance when false negative information about a politician is followed by a retraction, but when false positive information is followed by a retraction, respondents’ positive beliefs do not persevere. Instead, respondents over-correct—those who get false positive information and a correction actually end up with more negative opinions than those who never received either. We argue that these results are driven by respondents’ naïve theories about the effects of false information, which cause them to underestimate how much they need to adjust their evaluations after bogus negative information and overestimate the adjustment required for false positive information.

The belief perseverance literature largely focuses on opinion-oriented outcome measures. In the studies presented here, the outcome measures are either beliefs about future task performance (Ross and his colleagues) or evaluations of political candidates (Bullock; Cobb, Nyhan, and Reifler). A similar literature has developed examining how factual misinformation that has been stored in memory continues to exert influence even after a correction. These studies typically use fictional stories so that the researchers have complete control of the information provided to participants. These designs can help us better understand how memory and cognition affect corrective processes, but it is worth noting that participants typically lack strong prior beliefs about the fictional events or persons in the stories. As a result, their reactions may differ in important ways from those observed when partisanship or ideology is relevant (as in the Bullock example above).

For instance, research by University of Michigan psychologists examines how different aspects of corrections affect whether misinformation exerts a continuing influence on respondent beliefs. They examine both the timing of corrections and the inclusion of information that allows for causal inferences in either the misinformation or the correction.[64] The timing of corrections relative to misinformation has little effect on its continuing influence. The authors also show that misinformation is more likely to have a continued influence following a correction when the false belief offers a causal explanation for what participants observe (e.g., misinformation about volatile chemicals stored in a warehouse that catches fire). Similarly, corrections that offer a causal alternative (e.g., investigators found materials consistent with arson) are more effective than negations that do not contain information related to causation. These findings lead to the speculation that “misinformation that is only negated may interfere with subjects’ ability to generate alternatives, in effect fixing them in one interpretation of the event.”[65]

Other work examines how corrections that do not offer an alternative causal account may be effective.[66] Two factors matter for corrections—relevance and quality of information. Once misinformation is offered, it is assumed to be relevant. Challenging the misinformation without also addressing its (lack of) relevance makes it easier for respondents to continue using the misinformation. Similarly, if people receive both misinformation and a correction (especially from the same source), it may be difficult to judge the quality of the competing claims. In another experiment using the same warehouse fire scenario, clarifying the (ir)relevance or the (low) quality of the misinformation made the correction modestly more effective than a simple negation. They also examine an enhanced negation—rather than simply negating the claim that the warehouse that caught fire had volatile materials inside, they add that “no paint or gas had ever been stored” there. They find that this enhanced negation actually performs significantly worse than a simple negation, creating a backfire effect. They argue that the extremity of this correction conflicts with the causal interpretation that comes from the original misinformation about volatile materials, thereby undermining the correction’s effectiveness.

In a series of recent papers, University of Western Australia psychologists Ullrich Ecker, Stephan Lewandowsky, and colleagues examine other approaches to short-circuiting the continuing influence effect. Mirroring similar findings in the belief perseverance literature,[67] they find that warning experimental participants about the continuing influence effect diminishes the effect but does not eliminate it.[68] In studies that employ the warehouse fire design discussed above, they find that retractions cannot completely undo the continuing influence of misinformation. Interestingly, retractions are only effective against weakly encoded misinformation. The strength of retraction does not matter much at that point—both weak and strong retractions partially reduce the continuing influence effect. Additional work examines whether the continuing influence effect is related to emotion (highly emotive states have been shown to interfere with reasoning).[69] In a series of experiments, they find that retractions are no more effective following low-emotion misinformation (a plane crash caused by bad weather) than high-emotion misinformation (terrorists caused a plane crash).

Summary: The way in which human memory works can make it difficult to address misperceptions. Once a piece of information is encoded, it can be very difficult to eliminate its effects on subsequent attitudes and reasoning.

Sources matter: The powerful effects of speaker characteristics

A vast literature in psychology and political science has shown that statements are frequently more persuasive when they come from sources that are perceived as knowledgeable, trustworthy, or highly credible. Conversely, people are less likely to accept information from a source that is perceived as poorly informed, untrustworthy, not sharing the same values, etc. One application of this approach comes from Berinsky in the 2010 survey experiments described earlier. In these studies, he finds that some corrections are effective, particularly when the source of the correction is unexpected.[70]

For instance, a correction of the euthanasia rumor about health care reform increased rumor rejection among Republicans most when the correction is attributed to a Republican source. Because Republicans were expected to oppose Obama’s health care reform plan, a GOP source might have been more credible and therefore more persuasive. (However, rumor acceptance was actually lowest when the correction was attributed to a Democratic source; the difference is that there were far more “not sure” answers given in that case by Republican respondents.) Berinsky also reports that using an alternate correction condition in which a Republican official is quoted stating that Iraq did not have WMD attenuates the backlash effect among conservatives that we found in our experiments described above.[71]

Yale’s Dan Kahan and his colleagues argue that values are important in understanding how people respond to corrective messages. In one study, they find that respondents exposed to messages for and against the HPV vaccine were more likely to perceive the vaccine as risky when their values were closer to those of the anti-HPV advocate.[72] In another study, participants were more likely to view advocates as experts when the advocate held similar views to their own.[73]

Another concern is that journalists who give credence to fringe sources in media reports in pursuit of “balance” may increase misperceptions among viewers. Stanford political scientist Jon Krosnick and his colleagues tested the effects of including a climate “skeptic” who dissented from the scientific consensus about global warming in a television news story.[74] The presence of the skeptic significantly diminished respondent beliefs in global warming, the existence of a scientific consensus that it is occurring, and the role of humans in causing it.

Summary: The source of a given statement can have a significant effect on how that claim is interpreted by others. In politics, people are more receptive to sources that share their party affiliation or values as well as those that communicate unexpected information.

Negations, affirmations, and fluency: Repeating false claims can backfire

Another explanation for the persistence of myths and misperceptions is that corrections are often difficult to process cognitively and may reinforce the false claims they intend to debunk. For instance, University of Michigan psychologist Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues have documented an “illusion of truth” effect in which false claims are misremembered as true over time due to their familiarity. Their first study exposed participants to a series of health-related claims that were identified as true or false; some were presented once and some were presented three times.[75] Participants were more likely to misremember false statements as true than to remember true statements as false, especially after a three-day delay. In particular, while repetition helped young people reduce errors in remembering the truth value of a statement, it actually made elderly adults more likely to misremember false statements as true after a long delay. A second experiment found that similar effects occurred among seniors after only a twenty-minute delay when the truth value of a statement was only disclosed the last time they were exposed to it (rather than each time it was shown). In these cases, exposing seniors to the statement three times instead of once made them more likely to misremember false claims as true. This effect was not observed with younger adults.

A second study by Schwarz and colleagues documented similar “illusion of truth” effects using a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention poster of “Flu Vaccine Facts & Myths.”[76] Respondents who were only exposed to the facts presented in the poster viewed the vaccine more positively and were more likely to intend to get it, whereas those exposed to both the facts and myths viewed the vaccine less favorably and were less likely to intend to seek the vaccine after a delay. The authors attribute this result to the increased familiarity of the myths making them seem more plausible.

MIT’s Berinsky draws on this research in his own work, arguing that corrections may fail to reduce misperceptions because they increase the fluency of rumors for readers. In other words, corrections may make readers better able to repeat the rumor, which may in turn make it seem more true because fluency is often used as a heuristic.[77] To test for such an effect, Berinsky examined how the effectiveness of corrections changes over time. The hypothesis is that fluency may increase while memory for the correction may diminish. In a survey experiment, he found that a correction of the euthanasia myth actually appeared to increase belief in the rumor over time among Republicans. An additional experiment found that the effectiveness of corrections appeared to fade over time. Both findings could be the result of fluency effects, though the latter could also be interpreted as the effect of an experiment diminishing over time. To test this theory more rigorously, he asked a random group of respondents to recall the euthanasia rumor to see if the act of repetition promoted rumor acceptance by increasing fluency. Being asked to repeat the rumor appeared to modestly increase belief in it among participants exposed only to the rumor but did not have significant effects on those exposed to both the rumor and the correction.

A related cognitive issue is the difficulty of processing negations (i.e., “X is not Y”), which can end up inadvertently reinforcing the claim that the negation is intended to debunk. A recent study in psychology documents this phenomenon experimentally.[78] The authors find that negating descriptors that lack an opposite concept (e.g., “criminal”) can backfire. For example, saying that “John is not a criminal” may cause greater associations between the concept of John and criminality, reinforcing the association that the speaker intends to falsify. (By contrast, negations are more effective if the descriptor has an opposing concept [e.g., rich/poor].) Similarly, training participants to negate racial and gender stereotypes has been shown to strengthen implicit stereotypes of women relative to men and decrease implicit evaluations of blacks relative to whites, while training participants to affirm non-stereotypical information was effective.[79]

In collaboration with a team of Duke University students, we tested this approach during the 2008 election to see if it was more effective for Barack Obama to say he “is a Christian” rather than to say he is “not a Muslim.”[80] Our results were consistent with this prediction only when non-white experimental administrators were present (the study was administered on laptops at a hospital). We therefore attribute these results to an unexpected social desirability effect. When only white administrators were present, a video of Obama saying he is a Christian actually made Republicans more likely to say Obama is a Muslim and less likely to believe he is being honest about his religion—a finding that is consistent with our research showing how corrections can backfire.

Finally, a related study tested the effects of negating a false attack using fictional political candidates but varied whether participants were exposed to the attack or just the response (an approach also taken by Berinsky as described above).[81] The authors found that candidates were evaluated more negatively when they negated the false attack rather than affirmed the truth. However, this effect was concentrated among participants with no prior knowledge of the attack; among those who had already been exposed to the attack, the negation and affirmation responses were equivalent. In addition, respondents with more political expertise were more likely to view candidates who used a negation strategy negatively; there was no difference in candidate evaluation by strategy among less sophisticated respondents.

Summary: Attempts to correct false claims can backfire via two related mechanisms. First, repeating a false claim with a negation (e.g., “John is not a criminal”) leads people to more easily remember the core of the sentence (“John is a criminal”). Second, people may use the familiarity of a false claim as a heuristic for its accuracy. If the correction makes a claim seem more familiar, the claim may be more likely to be perceived to be true.

Identity and race: Obstacles to corrective information

An additional concern is that corrective messages can be undermined by the salience of race, ethnicity, religion, culture, or other aspects of social identity, particularly when the citizen in question does not share the same background or beliefs as the public figure in question. For example, a recent psychology study found that asking people about their own race in 2008 made undecided voters and supporters of John McCain more likely to explicitly endorse the claims that Obama is Muslim and that he is a socialist.[82] The authors attribute this effect to the salience of the social category difference between participants and Obama. Likewise, when respondents were asked about their age, which heightened the salience of their youth compared with McCain, Obama supporters and undecided voters were more likely to endorse the claim that the Arizona senator suffered from dementia.

A related experiment was conducted by Ohio State’s Erik Nisbet and Kelly Garrett using online participants in 2010. They found that unrelated cultural factors undermined the effectiveness of a correction of a rumor about the Imam behind the proposed Islamic cultural center that was falsely labeled the “Ground Zero mosque.” Results showed that a text rebuttal attributed to Factcheck.org was effective in reducing belief in the rumor when presented alone or with an image of the Imam in a suit. However, the rebuttal was ineffective when it was paired with an image of the Imam in traditional Middle Eastern attire. They found that the correction was also ineffective when the article described the Imam’s critical views of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East.

As discussed above, we also observed a related effect during our study of corrections of the Obama Muslim myth. Our results suggest that respondents were influenced by the race of the experimental administrators who were present when they took part in the study, which may have been the result of the sensitivity of the subject. However, we could not randomize the race of experimental administrators in our study, so our conclusions are tentative at this point. (We plan to conduct a followup study examining this effect in the future.)

Summary: When information about race or social identity is salient, it can undermine the effectiveness of corrective information, particularly when the target of the correction does not have the same background as the respondent.

Threats to control: Fuel for misperceptions

A different line of research proposes an alternate psychological mechanism for the problem of misperceptions. In some cases, people may believe in misperceptions like conspiracy theories because they feel a lack of control. In a paper published in Science in 2008, two management professors find that experimentally inducing a lack of control makes people more apt to see patterns where in fact there are none, including conspiracies.[83]

A group of University of Kansas psychologists make a similar argument in an article arguing that a perceived lack of control leads people to exaggerate the influence of their perceived enemies.[84] Given the adversarial nature of politics, these findings seem especially relevant to understanding conspiracy theories about one’s partisan or ideological adversaries. For instance, in a study conducted the day before the 2008 election, they found that participants in a threat condition were far more likely to believe an array of conspiratorial claims about their less preferred presidential candidate. However, the threat condition did not lead to more generalized beliefs in conspiracy theories—the increase was only seen in conspiracy beliefs directly tied to the “enemy” candidate.

Summary: When people feel a lack of control, they compensate with strategies that lead to greater acceptance of misperceptions.

Visuals: A promising approach to presenting corrections

Another reason corrections may fail to reduce misperceptions is that they are presented ineffectively. In particular, textual corrections may be relatively easy for respondents to counter-argue or ignore. We therefore also tested the effects of graphical corrections in our experiments on self-affirmation.[85] We find that presenting corrective information in graphical form is generally quite successful at increasing the accuracy of respondents’ beliefs about the number of insurgent attacks in Iraq after the U.S. troop surge, the change in payroll jobs in the U.S. between January 2010 and January 2011, and the change in global temperatures in the last thirty years. The final study, which focused on climate change, directly contrasted a graphic adapted from a NASA press release with equivalent textual information and found that the graphic was significantly more effective.

A related experiment tested the effects of Politifact’s “Truth-o-meter” graphics as well as the length of a fact-checking message.[86] The author found that the graphics had no direct effect on factual knowledge but that respondents exposed to longer fact-checking messages answered more questions correctly. The latter effect appeared to be the result of respondents spending more time reading the longer factchecks. (In the real world, of course, readers may not make such an effort.)

Summary: Graphics may be an effective way to present data designed to correct misperceptions, especially when people have false beliefs about changes in a quantitative variable. However, graphical descriptions of the accuracy of political statements were found to have no effect on factual knowledge.

Conclusions

The existing research has identified several conditions under which people are more or less likely to accept or reject corrections. Some of these conditions are directly tied to the nature of the misperception and how people relate to it. Misperceptions that are related to highly salient or controversial issues such as the war in Iraq or the economy are often especially persistent. In other words, the misperceptions that are the most difficult to correct tend to be the ones that matter most to people’s self-concept or worldview. Acknowledging unwelcome facts about such issues can be threatening. As a result, people tend to try to defend their prior beliefs rather than revise their views. Misperceptions related to race, ethnicity, and culture may also be especially stubborn when most people differ from the victim of the misperception on the characteristic in question.

In contrast, it appears to be easier to reduce misperceptions that are technical or quantitative in nature (e.g., the change in insurgent attacks after the troop surge in Iraq), especially when people do not have strong prior beliefs about these quantities and they are not directly linked to one’s support or opposition to a given policy or candidate. However, technical misperceptions that are more closely tied to a policy proposal, such as the false claim that President Bush’s tax cuts increased revenue, may be more difficult to correct. Finally, corrections that require proving a negative (e.g., that President Bush did not allow 9/11) are often especially ineffective given the difficulty of debunking conspiracy theories, their deep psychological roots, and the ineffectiveness of negations.

Recommendations

Given these constraints, we offer the following practical recommendations for journalists, educators, and others who wish to reduce the prevalence of misperceptions:

Get the story right the first time. Once an error is communicated and stored in people’s memories, it is difficult to undo. Even when people are exposed to a correction and acknowledge that the initial claim was false, the errant information may continue to influence their attitudes. In addition, people may misremember the false claim as true over time. Similarly, it is important to avoid speculation that may turn out to be false, particularly if it is speculation about why some event has occurred (or will occur). People are typically eager to explain unexpected events, and causal claims about why they occurred are especially difficult to correct when wrong.

Early corrections are better. News organizations should strive to correct their errors as quickly as possible and to notify the media outlets that disseminated them further. It is difficult to undo the damage from an initial error, but rapid corrections of online articles or video can ensure that future readers and other journalists are not misled. In particular, media outlets should correct online versions of their stories directly (with appropriate disclosures of how they were changed) rather than posting corrections at the end (which are likely to be ineffective). They should also take responsibility for ensuring that corrections are made to articles in news databases such as Nexis and Factiva.

Beware making the problem worse. Corrections can backfire and increase the prevalence of misperceptions in several ways. First, news reports seeking to correct a misperception may expose more people to false information and thereby increase belief in the myth rather than reduce it. Corrections may also increase the prevalence of a misperception among members of the most vulnerable group if they provoke them to defend their prior beliefs. Finally, even if people initially accept that a given claim is false, they may suffer from an “illusion of truth” over time and come to believe that it is accurate. These risks are unavoidable for anyone working in the field, but they are worth keeping in mind on a day-to-day basis. In particular, while journalists may be uncomfortable testing the language that they use due to professional norms, it is vital for civic and health educators to experimentally test marketing materials to ensure that they are effective.

Avoid negations. Stating a correction in the form of a negation may reinforce the misperception in question. Research and theory suggests that corrective affirmations (“John is exonerated”) are likely to be more effective than trying to negate a misperception (“John is not a criminal”).

Minimize repetition of false claims. The more times a false claim is repeated, the more likely people are to be exposed to it. The fewer people exposed to a false claim, the less likely it is to spread. However, the problem of repetition is about more than mere exposure (a concern that dates back to the controversy over repeating television ads during ad watch segments). It is also important not to repeat false claims because of the “fluency” effect. People are more likely to judge familiar claims as true. As false claims are repeated, they become more familiar and thus may come to seem more true to people.

Reduce partisan and ideological cues. The context in which misperceptions are addressed seems to play an important role in the effectiveness of corrections. When corrections are embedded in media coverage of partisan politics, they are frequently ineffective and may even make matters worse. People may rely on partisan cues within the story (e.g., that Democrats support a given claim) and ignore or reject the content of the correction. As a result, framing corrections around misleading statements by prominent political figures (as most news coverage and factchecking sites do) may be an ineffective means of reducing misperceptions. Unfortunately, corrections that do not identify a source are not only less newsworthy but may be more difficult for individuals to interpret and apply when they are later exposed to a misleading claim. At a minimum, presenting information in an authoritative manner with a minimum of partisan cues is likely to be more effective than the “Democrats say X, Republicans say Y” frames that are typically used.

Use credible sources; don’t give credence to the fringe. Sources matter when people evaluate factual claims. Corrections that come from unexpected or credible sources are likely to be more effective than those from the media or partisan sources. It is especially desirable to seek out experts who are speaking out against a misperception held by their ideological or partisan allies (this is a case in which partisan cues may be helpful in persuading people to accept counterattitudinal information). For instance, an ABCNews.com story on the “death panels” myth stated that “even [health care experts] who do not support the version of the health care reform bill now being discussed… note that these accusations are shocking, inflammatory and incorrect.”[87] Likewise, including pseudo-expert dissenters in stories on topics about which there is a scientific consensus can misinform the public about the available evidence and the views of the scientific community.

Use graphics where appropriate. When quantitative information can be presented in graphical form, it should be. Graphics appear to be an effective means of communicating information, especially about trends that may be the subject of misperceptions (the state of the economy under a given president, the number of casualties in a war, etc.).

Beware selective exposure. In a media marketplace with many options, people can make choices about the content they consume. In the political realm, they may seek out news outlets that are consistent with their ideological or partisan views. This problem of selective exposure can limit the effectiveness of corrections because media outlets may be less likely to correct misperceptions that are disproportionately held by their viewers or readers (e.g., MSNBC may correct conservative misperceptions more frequently than liberal ones). Targeting misperceptions that are likely to be held by an outlet’s viewers or readers will be more effective (albeit often unrealistic). In addition, journalists should be aware of the ways in which selective exposure can hinder the effectiveness of a given outlet’s efforts to correct misperceptions. People may tend to select the stories that reinforce their views and avoid those that make them uncomfortable. For instance, Republican Politifact readers may be more likely to read articles that fact-check statements by Democrats (and vice versa). Outlets should investigate how they can reduce this problem and encourage readers to be exposed to a more diverse stream of fact-checking articles. We also recommend The Debunking Handbook, a short pamphlet offering research-based recommendations for correcting misinformation that was written by Skeptical Science founder John Cook and University of Western Australia psychologist Stephen Lewandowsky (whose work we discuss above).[88] Despite these findings, many important questions remain unanswered that should be addressed in future studies. Here are some of the most important topics for researchers to consider:

- The process of rejecting corrections. As this review shows, corrections can sometimes work, sometimes make no difference, and sometimes backfire. More research is necessary to better understand exactly when (and why!) these differences occur. It is particularly important to understand the reasons that people reject corrections. Factors such as ideological differences, cognitive processes, source, etc. are all likely to play a role, but understanding each factor’s contribution requires additional research. This knowledge will help inform the design of future mitigation strategies.

- How much do media sources matter? Previous studies of source effects in correcting misperceptions have tended to focus on the partisanship, ideology, or affiliations of a speaker making a claim about a given issue. However, people get most of their political news from the media and may be more or less likely to distrust corrections based on the perceived slant of the outlet in question. Future studies should consider how partisanship and ideology interact with media slant to influence the effectiveness of corrections.

- The prevalence and effects of selective exposure. Researchers conducting experimental studies of misperceptions tend to randomize exposure to corrective information. In the real world, however, people have the option to select both media outlets and stories from a given outlet. Little is known about whether people who are misinformed are more likely to seek out belief-confirming stories or to avoid corrective information. In addition, we do not know the extent to which selective exposure is a problem among readers of fact-checking websites.

- Will causal corrections work in politics? Research using fictional, non-political scenarios suggests that misperceptions about the cause of a given event can be especially hard to negate. Providing an alternative causal account may be more effective. It is possible that this approach could be applied to political misperceptions. However, this approach has not yet been tested experimentally in published work.

- The role of political elites. Research on the psychological basis of misperceptions shows that threats to control can increase belief in conspiracy theories, while affirming people’s self-worth can make them more willing to acknowledge uncomfortable facts about politics. To date, both factors have been tested using artificial laboratory tasks. It would be worthwhile to test whether messages from political elites can successfully change respondents’ perceived sense of control or self-worth. If so, those messages might also affect respondents’ reported levels of misinformation via the mechanisms described above. This would be a difficult but important test of the empirical relevance of these theories.

- Are warnings effective in practice? Research in laboratory settings has suggested that alerting people to the lingering effect of debunked information can itself help alleviate the problem. It is not clear, however, whether warning people outside of the lab that false and discredited information may continue to influence their opinions will actually diminish the problem of misperceptions.

- How much “hidden knowledge” is there? Modest financial incentives closed a relatively small portion of the factual knowledge gap between Democrats and Republicans. However, when the individuals most likely to hold a given misperception are allowed to affirm their self-worth, they are less likely to endorse false or unsupported claims. One important question for future research is to determine how much “hidden knowledge” is held by people who endorse misperceptions. In the end, misperceptions are the inevitable result of the limitations of human information processing and the demand for misinformation in a polarized society. Given the difficulties of improving human cognition or reducing the demand for false claims, it is worth asking whether civil society can instead affect the supply of misinformation at the elite level. First, as one of us (Nyhan) has argued, it may be more effective to “name and shame” the dishonest politicians and pundits who promote misinformation. Doing so could increase the reputational costs of false claims and thereby help change future elite behavior, particularly if media outlets become more selective about covering serial dissemblers.[89] These effects will be compounded if corrections help to create an elite consensus rejecting a particularly notorious false claim. The so-called “one-sided information flows” that result from elite unity create pressure on individual political figures to not make false statements (as Texas governor Rick Perry discovered when he said he didn’t know if President Obama was a citizen[90]) and can transform public opinion.[91] Even if corrections are sometimes ineffective at the individual level, fact-checking efforts that change the balance of elite beliefs on an issue can have powerful effects.

Notes

- Scripps Howard/Ohio University poll, July 2006. Nyhan, Brendan. 2010. “Why the ‘Death Panel’ Myth Wouldn’t Die: Misinformation in the Health Care Reform Debate.” The Forum 8(1).

- CNN/Opinion Research poll, July 16-21, 2010.

- WorldPublicOpinion.org. 2010. “American Public Vastly Overestimates Amount of U.S. Foreign Aid.” http://www.worldpublicopinion.org/pipa/articles/ brunitedstatescanadara/670.php

- Bartels, Larry M. 2002. “Beyond the Running Tally: Partisan Bias in Political Perceptions.” Political Behavior 24(2): 117-150.

- Nyhan, Brendan and Jason Reifler. 2010. “When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions.” Political Behavior 32(2): 303-330.

- See, for example, Delli Carpini, Michael X. and Scott Keeter (1996). What Americans Know about Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- For a more detailed definition and discussion of alternate approaches, see Nyhan and Reifler 2010. A contrasting perspective is presented in the following article, which finds that student respondents had relatively accurate factual beliefs about the war in Iraq but differed in their interpretations of those facts: Gaines, Brian J., James H. Kuklinski, Paul J. Quirk, Buddy Peyton and Jay Verkuilen. 2007. “Interpreting Iraq: Partisanship and the Meaning of Facts.” Journal of Politics 69(4): 957-974.

- Elliot, Justin. 2011. “Trig Trutherism: The definitive debunker.” Salon.com. http://politics.salon. com/2011/04/22/sarah_palin_trig_conspiracy_theory/

- Kull, Steven, Clay Ramsay, and Evan Lewis. 2003. “Misperceptions, the Media, and the Iraq War.” Political Science Quarterly 118(4):569–598.

- Sides, John and Jack Citrin. 2007. “How Large the Huddled Masses? The Causes and Consequences of Public Misperceptions about Immigrant Populations.” Paper presented at the 2007 annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL. Enos, Ryan. 2010. “Are Illegal Immigrants Everywhere? Will it Change Your Vote?” YouGov.com. http:// today.yougov.com/news/2010/11/01/illegal-immigration-might-be-election-issue/

- Enos, Ryan. 2010. “Know Anybody Making $250,000?” YouGov.com. http://today.yougov.com/ news/2010/10/29/know-anybody-making-250000/

- Sides, John. N.d. “Stories, Science, and Public Opinion about the Estate Tax.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. 2010. “Growing Number of Americans Say Obama is a Muslim.” http://www.people-press.org/2010/08/19/ growing-number-of-americans-say-obama-is-a-muslim/

- Nyhan 2010.

- The Lancet. 2010. “Retraction—Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children.” Published online February 2, 2010.

- Gabriel, Trip. 2011. “With Stakes for Bachmann Higher Now, Her Words Get in the Way.”’ New York Times September 16 p. A16.

- Palin, Sarah. 2009. “Statement on the Current Health Care Debate.” August 7, 2009. http://www.facebook. com/note.php?note_ id=113851103434&ref=mf

- Factcheck.org. 2004. “Republican-funded Group Attacks Kerry’s War Record.” August 6, 2004 (updated August 22, 2004). http://www.factcheck.org/republican-funded_group_attacks_kerrys_war_record.html

- Eilperin, Juliet. 2002. “Democrat Implies Sept. 11 Administration Plot.” Washington Post, April 12, 2002.

- Noah, Timothy. 2003. “Whopper of the Week: Howard Dean.” Slate.com, December 13, 2003. http:// www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/chatterbox/2003/12/whopper_howard_dean.single.html

- Garrett, R. Kelly. 2011. “Troubling consequences of the Internet for political rumoring.” Human Communication Research, 37(2):255-274.

- Nyhan 2010.

- Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. 2009. “Health care reform closely followed, much discussed.” http://www.people-press.org/2009/08/20/ health-care-reform-closely-followed-much-discussed/

- Bartels 2002.

- Scripps Howard/Ohio University poll, July 2006. Public Policy Polling poll, September 2009. Berinsky, Adam. 2010. “Berinsky: Poll Shows False Obama Beliefs A Function of Partisanship.” Pollster.com. http:// www.pollster.com/blogs/poll_shows_false_obama_beliefs.php?nr=1

- Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. 2010. “Growing Number of Americans Say Obama is a Muslim.” http://www.people-press.org/2010/08/19/ growing-number-of-americans-say-obama-is-a-muslim/

- Travis Shannon. 2010. “CNN Poll: Quarter doubt Obama was born in U.S.” CNN.com. http://politicalticker.blogs.cnn.com/2010/08/04/cnn-poll-quarterdoubt-president-was-born-in-u-s/?fbid=Y8Ysrq0EY3i Berinsky 2010. Cohen, John. 2011. “Poll: Number of ‘birthers’ plummets.” WashingtonPost.com, May 5, 2011. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ behind-the-numbers/post/number-of-birthers-plummets/2011/05/04/AF3GAZxF_blog.html

- Howard Lavine, Christopher Johnston, and Marco Steenbergen. N.d. The Ambivalent Partisan: How Critical Loyalty Promotes Democracy. Oxford University Press.

- Jerit, Jennifer and Jason Barabas. N.d. “Partisan Perceptual Bias and the Information Environment.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Jerit, Jennifer and Jason Barabas. 2006. “Bankrupt Rhetoric: How Misleading Information Affects Knowledge About Social Security.” Public Opinion Quarterly 70(3): 278-303.

- Taber, Charles S. and Milton Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50(3):755–769

- Sides, John. 2010. “Why do more people think Obama is a Muslim?” WashingtonPost.com, August 26, 2010. http://voices.washingtonpost.com/ezra-klein/2010/08/ why_do_more_people_think_obama.html

- Kahan, Dan M., Ellen Peters, Donald Braman, Paul Slovic, Maggie Wittlin, Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, and Gregory Mandel. N.d. “The Tragedy of the Risk-Perception Commons: Culture Conflict, Rationality Conflict, and Climate Change.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Gilens, Martin. 2001. “Political Ignorance and Collective Policy Preferences.” American Political Science Review 95(2):379-396.

- Sides N.d.

- Howell, William G. and Martin R. West. 2009. “Educating the Public.” Education Next 9(3):40-47.

- Suzanne Mettler and Matt Guardino, “From Nudge to Reveal,” in Suzanne Mettler, 2011, The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy, University of Chicago Press.

- Kuklinski, James H., Paul J. Quirk, Jennifer Jerit, David Schweider, and Robert F. Rich. 2000. “Misinformation and the Currency of Democratic Citizenship.” Journal of Politics 62(3):790- 816.

- Sides and Citrin 2007.

- Berinsky, Adam. 2007. “Assuming the Costs of War: Events, Elites, and American Public Support for Military Conflict.” Journal of Politics 69(4):975-997.

- Kunda, Ziva. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin 108(3): 480-498. Molden, Daniel C. and E. Tory Higgins. 2005. “Motivated Thinking.” In Keith J. Holyoak and Robert G. Morrison, eds., The Cambridge Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Taber and Lodge 2006. Stroud, Natalie Jomini. 2008. “Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure.” Political Behavior 30(3):341–366. Iyengar, Shanto and Kyu S. Hahn. 2009. “Red media, blue media: Evidence of ideological selectivity in media use.” Journal of Communication 59(1):19–39. Iyengar, Shanto, Kyu S. Hahn, Jon A. Krosnick, and John Walker. 2008. “Selective exposure to campaign communication: The role of anticipated agreement and issue public membership.” Journal of Politics 70(1):186–200.

- Garrett, R. Kelly. 2009. “Echo chambers online?: Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14 (2): 265-85. Garrett, R. Kelly. 2009. “Politically motivated reinforcement seeking: Reframing the selective exposure debate.” Journal of Communication 59 (4): 676-99. Garrett, R. Kelly. Forthcoming. “A turn toward avoidance? Selective exposure to online political information, 2004-2008.” Political Behavior.

- Lord, Charles G., Lee Ross, and Mark R. Lepper. 1979. “Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37(11):2098–2109. Edwards, Kari and Edward E. Smith. 1996. “A disconfirmation bias in the evaluation of arguments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71(1):5–24. Taber and Lodge 2006.

- Taber and Lodge 2006.

- See, for instance, the following exchange: Jost, John T., Jack Glaser, Arie W. Kruglanski, and Frank J. Sulloway. 2003. “Political conservatism as motivated social cognition.” Psychological Bulletin 129(3): 339- 375. Greenberg, Jeff, and Eva Jonas. 2003. “Psychological Motives and Political Orientation – The Left, the Right, and the Rigid: Comment on Jost et al. (2003).” Psychological Bulletin 129(3): 376-382. Jost, John T., Jack Glaser, Arie W. Kruglanski, and Frank J. Sulloway. 2003. “Exceptions That Prove the RuleUsing a Theory of Motivated Social Cognition to Account for Ideological Incongruities and Political Anomalies: Reply to Greenberg and Jonas (2003).” Psychological Bulletin 129(3): 383-393.

- Jacks, Julia Zuwerink and Kimberly A. Cameron. 2003. “Strategies for Resisting Persuasion.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 25(2): 145-161.

- Vallone, Robert P., Lee Ross, and Mark R. Lepper. 1985. “The Hostile Media Phenomenon: Biased Perception and Perceptions of Media Bias in Coverage of the ‘Beirut Massacre.’” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49(3): 577-585.

- Munro, Geoffrey D. and Peter H. Ditto. 1997. “Biased Assimilation, Attitude Polarization, and Affect in Reactions to Stereotype-Relevant Scientific Information.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23(6): 636-653.

- Nyhan and Reifler 2010.

- Berinsky, Adam. N.d. “Rumors, Truth, and Reality: A Study of Political Misinformation.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Nyhan, Brendan and Jason Reifler. N.d. “Opening the Political Mind? The effects of self-affirmation and graphical information on factual misperceptions.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Bullock, John G., Alan S. Gerber, and Gregory A. Huber. N.d. “Partisan Bias in Factual Beliefs about Politics.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Pfau, Michael and Allen Louden. 1994. “Effectiveness of Adwatch Formats in Deflecting Political Attack Ads.” Communication Research 21(3): 325-341.

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall. 1992. Dirty Politics: Deception, Distraction, and Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cappella, Joseph N. and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. 1994. “Broadcast Adwatch Effects: A Field Experiment.” Communication Research 21(3): 342-365.

- O’Sullivan, Patrick B. and Seth Geiger. 1995. “Does the Watchdog Bite? Newspaper Truthboxes and Political Attack Ads” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 72: 771-785.

- Leshner, Glenn. 2001. “Critiquing the Image: Testing Images Adwatches as Journalistic Reform.” Communication Research 28(2): 181-207.