Using the 2015 budget to break down how the process works, from submission to approval and everything in between.

Introduction

The United States federal government expects to spend $3.8 trillion dollars in 2015 – that sounds like a lot of money, and it is. That’s about $12,000 for each woman, man and child living in the United States. It’s also about 21 percent of the entire United States economy.1

But the government is not just a bill collector and spender. At its best, each of the dollars our government spends can advance the common good and Americans’ quality of life through public investments in infrastructure, systems and structures that only government is positioned to make – investments in things like court systems, clean water, transportation, income security, energy and education.

A few examples: the federal government provides an average of thirty percent of state government revenues for things like transportation and education; most Americans will rely on government programs like Social Security and Medicare as they age; and half of the nation’s public schools receive federal aid. Without the federal government, our communities and families would not be the same.

And we all contribute to government, whether we engage through voting or other civic involvement, or whether we simply go to work and pay our taxes. In fact, in 2015, 80 percent of federal revenues will come from individual income and payroll taxes.

It is in all of our best interests – and it is our responsibility — to see that our tax dollars are raised and spent in ways that reflect our priorities. To do that we need to know where that money is going, and how budget decisions are made. Federal Budget 101 gives you that crucial information.

Throughout Federal Budget 101, you’ll see that some words are in bold text. Those are words you can find in the Federal Budget Glossary [at the end].

An Overview of the Process

Introduction

The vision of democracy is that the federal budget – and all activities of the federal government – reflects the values of a majority of Americans. Yet many people feel that the federal budget does not reflect their values and that the budgeting process is too difficult to understand, or that they can’t make a difference.

And it is a complicated process. Many forces shape the federal budget. Some of them are forces written into law – like the president’s role in drafting the budget – while other forces stem from the realities of our political system.

And while the federal budget may not currently reflect the values of a majority of Americans, the ultimate power over the U.S. government lies with the people. We have a right and responsibility to choose our elected officials by voting, and to hold them accountable for representing our priorities. The first step is to understand what’s going on.

An Evolving Process

The U.S. Constitution designates the “power of the purse” as a function of Congress.2 That includes the authority to create and collect taxes and to borrow money when needed. The Constitution does not, however, specify how Congress should exercise these powers or how the federal budget process should work. It doesn’t specify a role for the president in managing the nation’s finances, either.

As a result, the budget process has evolved over time. Over the course of the twentieth century, Congress passed key laws that shaped the budgeting process into what it is today, and formed the federal agencies – including the Office of Management and Budget, the Government Accountability Office, and the Congressional Budget Office – that provide oversight and research crucial to creating the budget.3 The process as it’s supposed to work is described here.

Before the Budget

Congress creates a new budget for our country every year. This annual congressional budget process is also called the appropriations process.

Appropriations bills specify how much money will go to different government agencies and programs. In addition to these funding bills, Congress must pass legislation that provides the federal government the legal authority to actually spend the money.4 These laws are called authorization bills, or authorizations. Authorizations often cover multiple years, so authorizing legislation does not need to pass Congress every year the way appropriations bills do. When a multi-year authorization expires, Congress often passes a reauthorization to continue the programs in question.

Authorizations also serve another purpose. There are some types of spending that are not subject to the appropriations process. Such spending is called direct or mandatory spending, and authorizations provide the legal authority for this mandatory spending.5 Federal spending for Social Security and Medicare benefits is part of mandatory spending, because according to the authorization, the government must by law pay out benefits to all eligible recipients.

How Does the Federal Government Create a Budget?

Overview

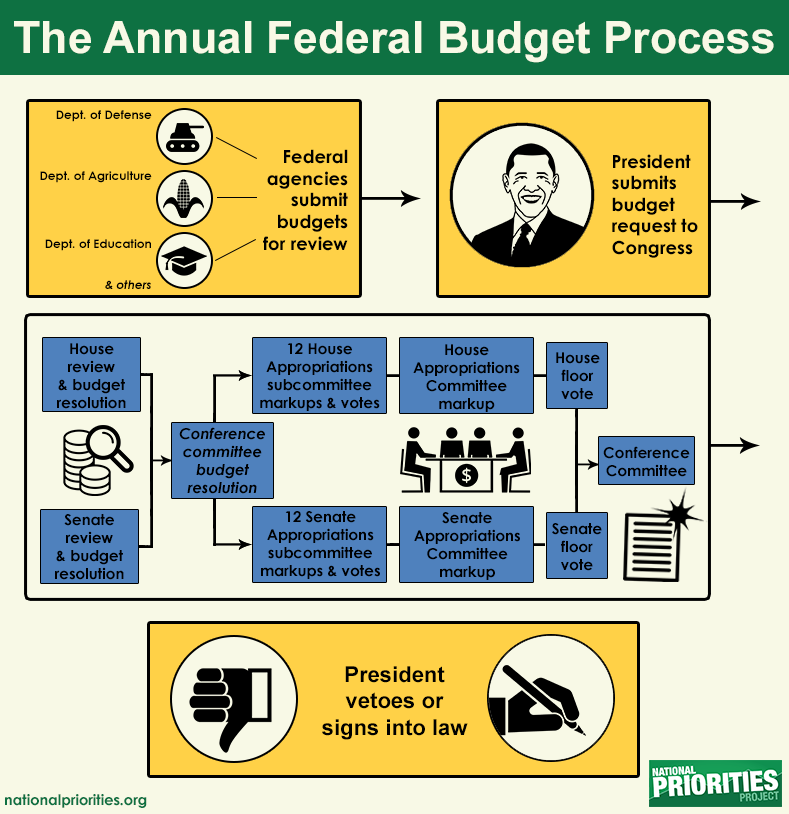

There are five key steps in the federal budget process:

- The President submits a budget request to Congress

- The House and Senate pass budget resolutions

- House and Senate Appropriations subcommittees “markup” appropriations bills

- The House and Senate vote on appropriations bills and reconcile differences

- The President signs each appropriations bill and the budget becomes law

Step 1: The President Submits a Budget Request

The president sends a budget request to Congress each February for the coming fiscal year, which begins on Oct. 1.6

To create his (or her) request, the President and the Office of Management and Budget solicit and accept budget requests from federal agencies, outlining what programs need more funding, what could be cut, and what new priorities each agency would like to fund.

The president’s budget request is just a proposal. Congress then passes its own appropriations bills; only after the president signs these bills (in step five) does the country have a budget for the new fiscal year.7

Step 2: The House and Senate Pass Budget Resolutions

After the president submits his or her budget request, the House Committee on the Budget and the Senate Committee on the Budget each write and vote on their own budget resolutions.8

A budget resolution is not a binding document, but it provides a framework for Congress for making budget decisions about spending and taxes. It sets overall annual spending limits for federal agencies, but does not set specific spending amounts for particular programs. After the House and Senate pass their budget resolutions, some members from each come together in a joint conference to iron out differences between the two versions, and the resulting reconciled version is then voted on again by each chamber.

Step 3: House and Senate Subcommittees “Markup” Appropriation Bills

The Appropriations Committees in both the House and the Senate are responsible for determining the precise levels of budget authority, or allowed spending, for all discretionary programs.9

The Appropriations Committees in both the House and Senate are broken down into smaller appropriations subcommittees. Subcommittees cover different areas of the federal government: for example, there is a subcommittee for defense spending, and another one for energy and water. Each subcommittee conducts hearings in which they pose questions to leaders of the relevant federal agencies about each agency’s requested budget.10

Based on all of this information, the chair of each subcommittee writes a first draft of the subcommittee’s appropriations bill, abiding by the spending limits set out in the budget resolution. All subcommittee members then consider, amend, and finally vote on the bill. Once it has passed the subcommittee, the bill goes to the full Appropriations Committee. The full committee reviews it, and then sends it to the full House or Senate.

Step 4: The House and Senate Vote on Appropriations Bills and Reconcile Differences

The full House and Senate then debate and vote on appropriations bills from each of the 12 subcommittees.

After both the House and Senate pass their versions of each appropriations bill, a conference committee meets to resolve differences between the House and Senate versions. After the conference committee produces a reconciled version of the bill, the House and Senate vote again, but this time on a bill that is identical in both chambers. After passing both the House and Senate, each appropriations bill goes to the president.11

Step 5: The President Signs Each Appropriations Bill and the Budget Becomes Law

The president must sign each appropriations bill after it has passed Congress for the bill to become law. When the president has signed all 12 appropriations bills, the budget process is complete. Rarely, however, is work finished on all 12 bills by Oct. 1, the start of the new fiscal year.

This chart shows how all of these pieces fit together to make the annual federal budget process.

Continuing Resolutions and Omnibus Bills

When the budget process is not complete by Oct. 1, Congress may pass a continuing resolution so that agencies continue to receive funding until the full budget is in place.12 A continuing resolution provides temporary funding for federal agencies until new appropriations bills become law. When Congress does not pass a continuing resolution by October 1, it can result in a government shutdown, as in 2013.

When Congress can’t agree on 12 separate appropriations bills, it will often resort to an omnibus bill – a single funding bill that encompasses all 12 funding areas. The fiscal year 2015 budget was the result of a combined omnibus and continuing resolution enacted by Congress in December of 2014.

Supplemental Appropriations

From time to time the government has to respond to unanticipated situations for which there is no funding, such as natural disasters. In these cases the government has to allocate additional resources and do so in a timely manner. This type of funding is allocated through legislation known as supplemental appropriations.

It’s Even Messier than It Sounds

So that’s how the budgeting process is supposed to go. And while that sounds pretty complicated, in practice, it’s even more so. Other factors that include the state of the economy, party politics, differing economic philosophies, and the impact of lobbying and campaign contributions also have a considerable impact on the federal budget process.

Federal Revenue: Where Does the Money Come From?

The federal government raises trillions of dollars in tax revenue each year, though a variety of taxes and fees. Some taxes fund specific government programs, while other taxes fund the government in general. When all taxes for a given year are insufficient to cover all of the government’s expenses – which has been the case in 45 out of the last 50 years13 – the U.S. Treasury borrows money to make up the difference.

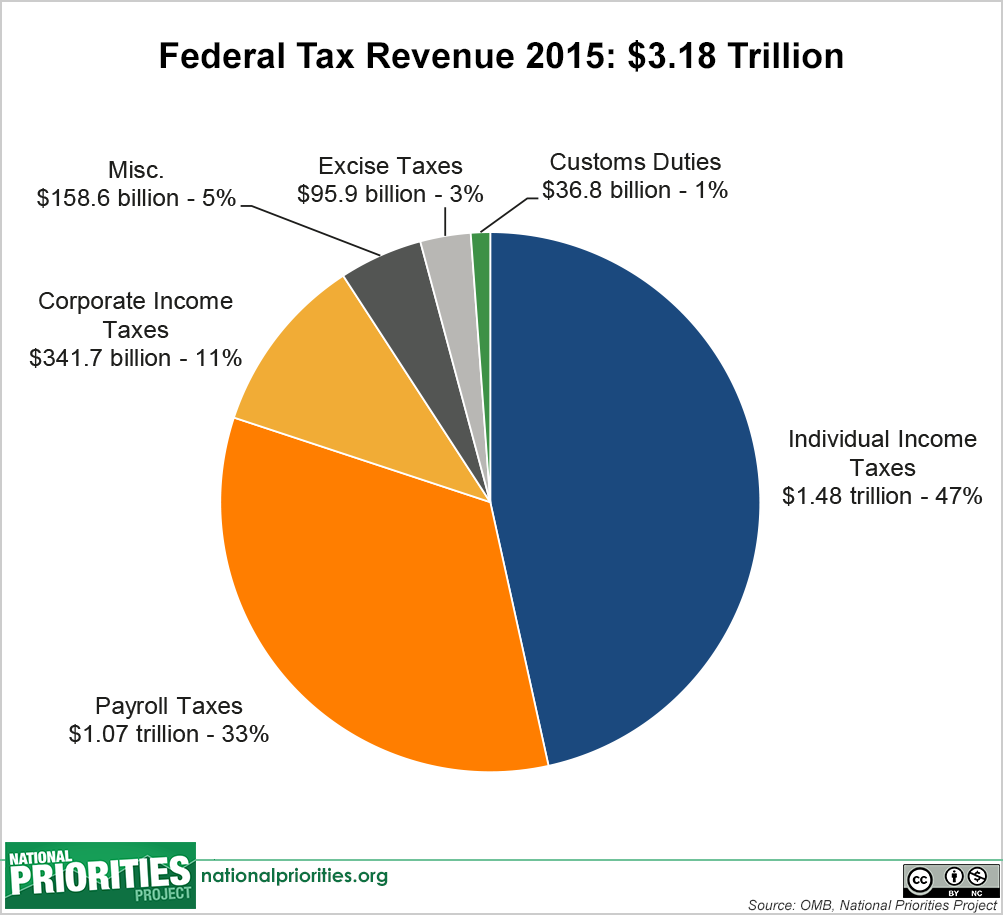

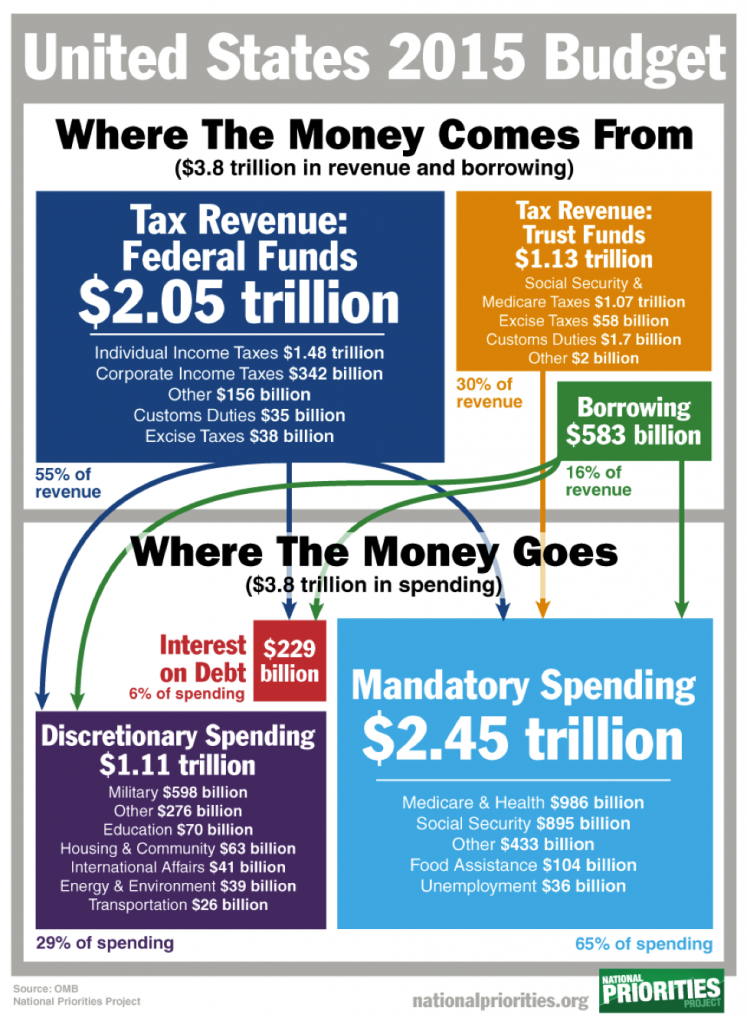

In 2015, total federal revenues in fiscal year 2015 are expected to be $3.18 trillion.14 These revenues come from three major sources:

- Income taxes paid by individuals: $1.48 trillion, or 47% of all tax revenues.

- Payroll taxes paid jointly by workers and employers: $1.07 trillion, 34% of all tax revenues.

- Corporate income taxes paid by businesses: $341.7 billion, or 11% of all tax revenues.

There are also a handful of other types of taxes, like customs duties and excise taxes that make up much smaller portions of federal revenue. Customs duties are taxes on imports, paid by the importer, while excise taxes are taxes levied on specific goods, like gasoline. This pie chart below shows how much each of these revenue sources is expected to bring in during fiscal year 2015.

Once they are paid into the Treasury, income taxes and corporate taxes are designated as federal funds, while payroll taxes become trust funds. Federal funds are general revenues, meaning Congress and the president can decide to spend them on just about anything when they conduct the annual appropriations process (see our explanation of the federal budget process). Unlike federal funds, trust funds can be used only to pay for specific programs. The vast majority of trust fund revenues pay for Social Security and Medicare.

Income Taxes

The U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 8) grants Congress the power to collect taxes. Early federal taxation was mostly in the form of excise taxes on goods such as alcohol and tobacco. Although an income tax existed briefly during the Civil War, it wasn’t until 1913, with the ratification of the XVI Amendment to the Constitution, that income taxes became permanent. At that time fewer than 1 percent of people with the highest incomes paid income taxes.

Nowadays, more than 100 million American households file a federal tax return each year, and those income taxes make up the federal government’s single largest revenue source.15 The income tax system is designed to be progressive. That is, the wealthy are meant to pay a larger percentage of their earnings than middle- or low-income earners. Due to the complexity of the tax code, however, this is not always the way it works out.

Corporate Taxes

Corporations pay income taxes similar to those paid by workers. Depending on how much profit a corporation makes, it pays a marginal tax rate anywhere from 15 to 35 percent.16 The top marginal tax rate for corporations, 35 percent, applies to taxable income over $18.3 million. As you can see in the line chart below, individual income taxes make up a much larger share of all federal tax revenues than corporate taxes do, in part because the wages and salaries of all Americans are much larger than profits of all U.S. corporations. The share of federal tax revenue paid by corporations has also declined substantially over time.

While the official tax rate for most corporations is 35 percent, the effective tax rate – that’s the percentage of profits a corporation actually pays in taxes – varies enormously from one corporation to the next.17 That variation is the result of incredible complexity in the tax code as well as corporations’ varying exploitation of “loopholes” to avoid tax liability. Loopholes refer to provisions in the tax code that exempt certain activities from regular taxation. For example, multinational corporations can allocate profits to overseas operations and reduce their tax liability by doing so.

Payroll Taxes

While individual and corporate income taxes are designated as federal funds, as described above, payroll taxes are designated as trust funds. Trust funds can be used only for very specific purposes – mainly to pay for Social Security and Medicare. Social Security, officially called the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, is meant to ensure that elderly and disabled people do not live in poverty. Medicare is a federal program that provides health care coverage for senior citizens and the disabled.

Taxes to finance Social Security were established in 1935 as a payroll deduction – these are the payroll taxes you see taken directly out of your paycheck, labeled on pay stubs as Social Security and Medicare taxes or as “FICA,” an abbreviation for the Federal Insurance Contributions Act. That’s the law that mandates funding for Social Security by means of a payroll deduction.

The deductions from your paycheck are only half the story of payroll taxes. Employees and employers each pay 6.2 percent of wages into Social Security and 1.45 percent into Medicare. That means your employer deducts 7.65 percent of your wages from your paycheck to contribute to those programs, and then your employer contributes an equal amount, though you never see documentation of your employer’s contribution.

Borrowing

In most years, the federal government spends more money than it takes in from tax revenues. To make up the difference, the Treasury borrows money by issuing bonds. Anyone can buy Treasury bonds, and, in effect, lend money to the Treasury by doing so. In fiscal year 2015, the federal government is expected to borrow $583 billion to make up the difference between $3.18 billion in revenues and $3.8 trillion in spending. Borrowing constitutes a major source of revenue for the federal government. Down the road, however, the Treasury must pay back the money it has borrowed, and pay interest as well. In 2015, the federal government will pay $229 billion in interest on the national debt.

Federal Spending: Where Does the Money Go?

In fiscal year 2015, the federal budget is $3.8 trillion. These trillions of dollars make up about 21 percent of the U.S. economy (as measured by Gross Domestic Product, or GDP). It’s also about $12,000 for every woman, man and child in the United States.

So where does all that money go?

Mandatory and Discretionary Spending

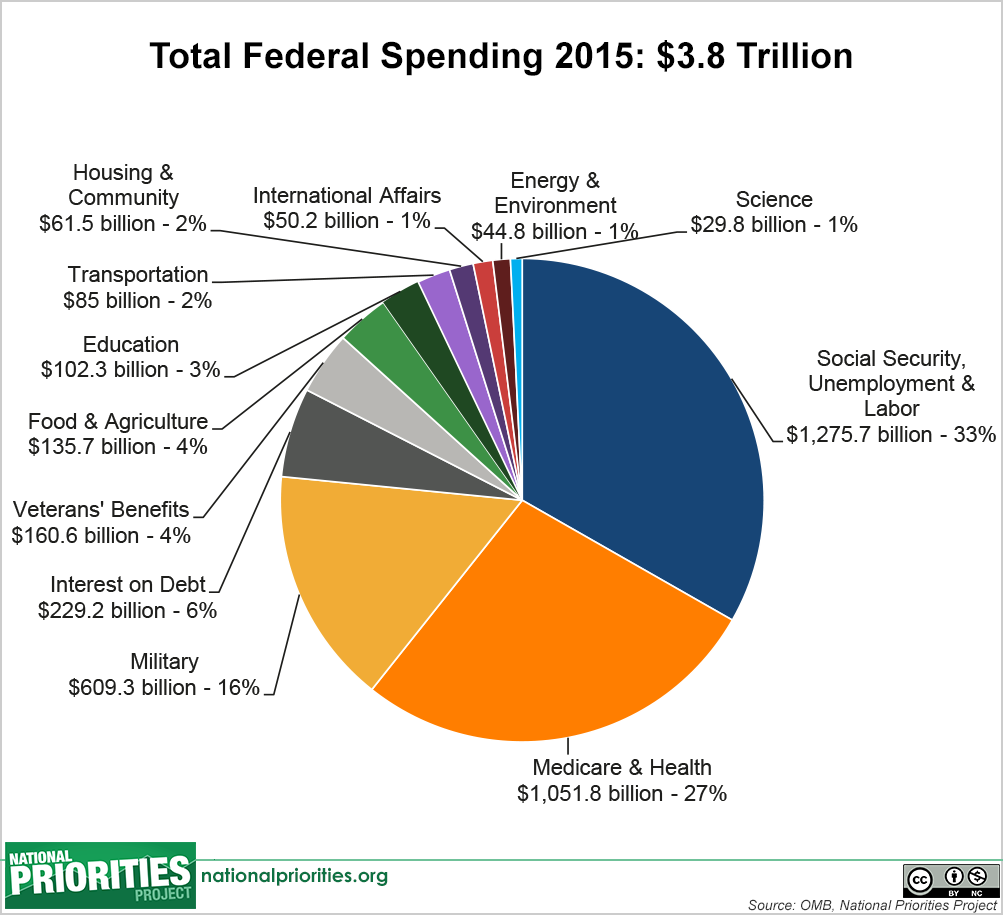

The U.S. Treasury divides all federal spending into three groups: mandatory spending, discretionary spending and interest on debt. Mandatory and discretionary spending account for more than ninety percent of all federal spending, and pay for all of the government services and programs on which we rely. Interest on debt, which is a much smaller amount than the other two categories, is the interest the government pays on its accumulated debt, minus interest income received by the government for assets it owns. The pie chart shows federal spending in 2015 broken into these three categories.

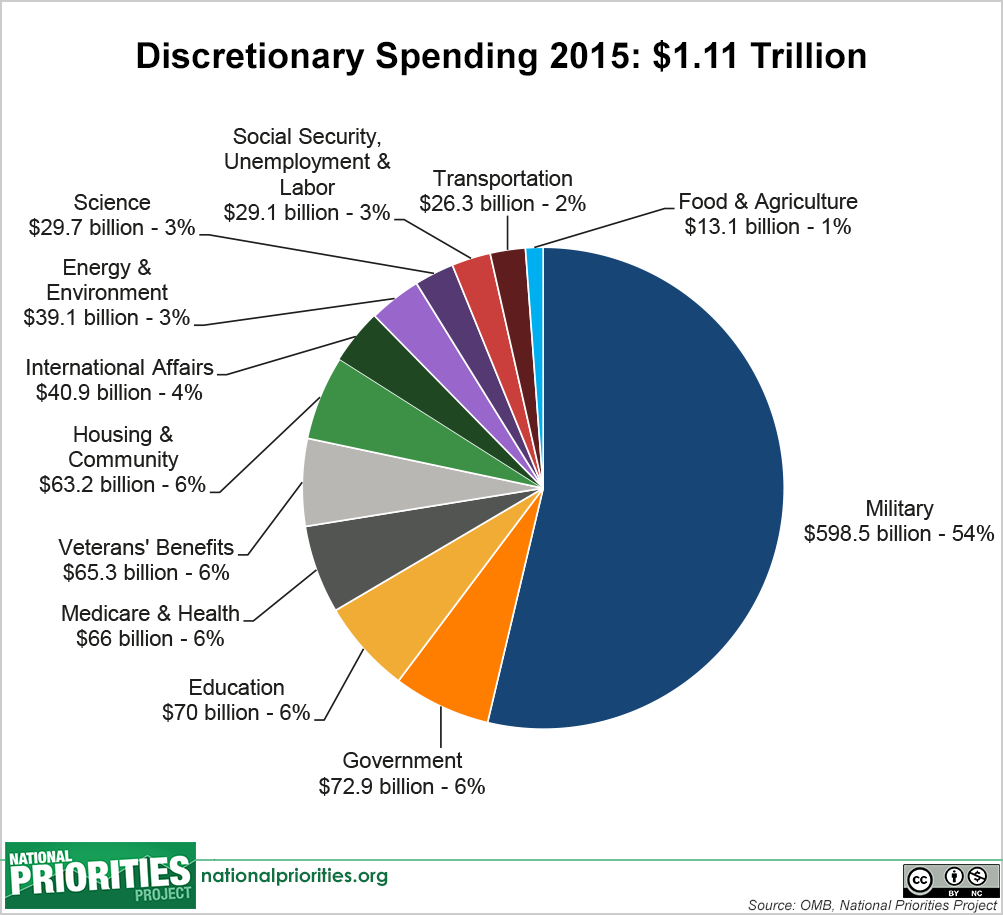

Discretionary Spending

Discretionary spending refers to the portion of the budget that is decided by Congress through the annual appropriations process each year. These spending levels are set each year by Congress.

This pie chart shows how Congress allocated $1.11 trillion in discretionary spending in fiscal year 2015.

By far, the biggest category of discretionary spending is spending on the Pentagon and related military programs. Examples of other well-known programs paid for by discretionary spending include the early childhood education program Head Start (included in Housing & Community), Title I grants to disadvantaged schools and Pell grants for low-income college students (Education), food assistance for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), training and placement for unemployed people provided by Workforce Investment Boards (in Social Security, Unemployment and Labor), and scientific research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF), among many others.

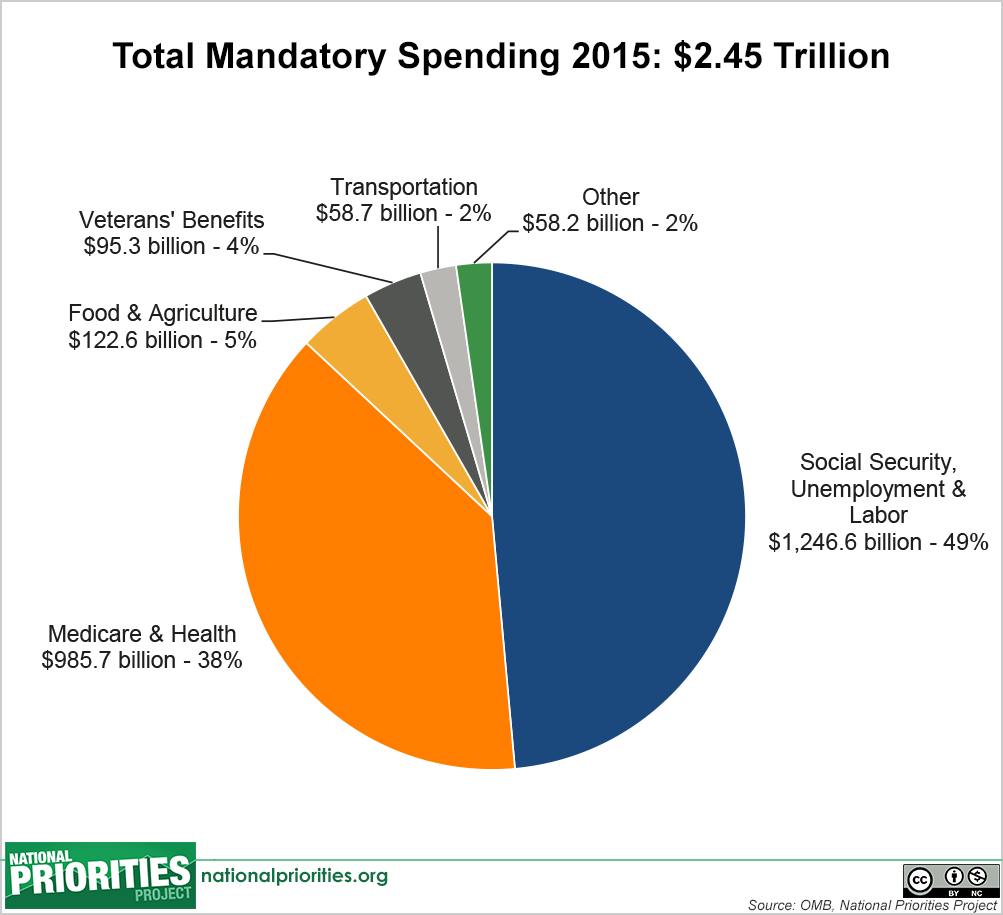

Mandatory Spending

Mandatory spending is spending that Congress legislates outside of the annual appropriations process, usually less than once a year. It is dominated by the well-known earned-benefit programs Social Security and Medicare. It also includes widely used safety net programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), and a significant amount of federal spending on transportation, among other things.

Many mandatory programs’ spending levels are determined by eligibility rules. For example, Congress decides to create a program like Social Security. It then sets criteria for determining who is eligible to receive benefits from the program, and benefit levels for people who are eligible. The amount of money spent on Social Security each year is then determined by how many people are eligible and apply for benefits.

Congress therefore does not decide each year to increase or decrease the budget for Social Security or other earned benefit programs. Instead, it periodically reviews the eligibility rules and may change them in order to exclude or include more people, or offer more or less generous benefits to those who are eligible, and therefore change the amount spent on the program.

Mandatory spending makes up nearly two-thirds of the total federal budget. Social Security alone comprises more than a third of mandatory spending and around 23 percent of the total federal budget. Medicare makes up an additional 23 percent of mandatory spending and 15 percent of the total federal budget.

This chart shows where the projected $2.45 trillion in mandatory spending will go in fiscal year 2015.

All Federal Spending

Finally, putting together discretionary spending, mandatory spending, and interest on the debt, you can see how the total federal budget is divided into different categories of spending. This pie chart shows the breakdown $3.8 trillion in combined discretionary, mandatory, and interest spending budgeted by Congress in fiscal year 2015.

Spending and Revenue

Here’s how federal spending and revenue in 2015 add up:

Spending in the Tax Code

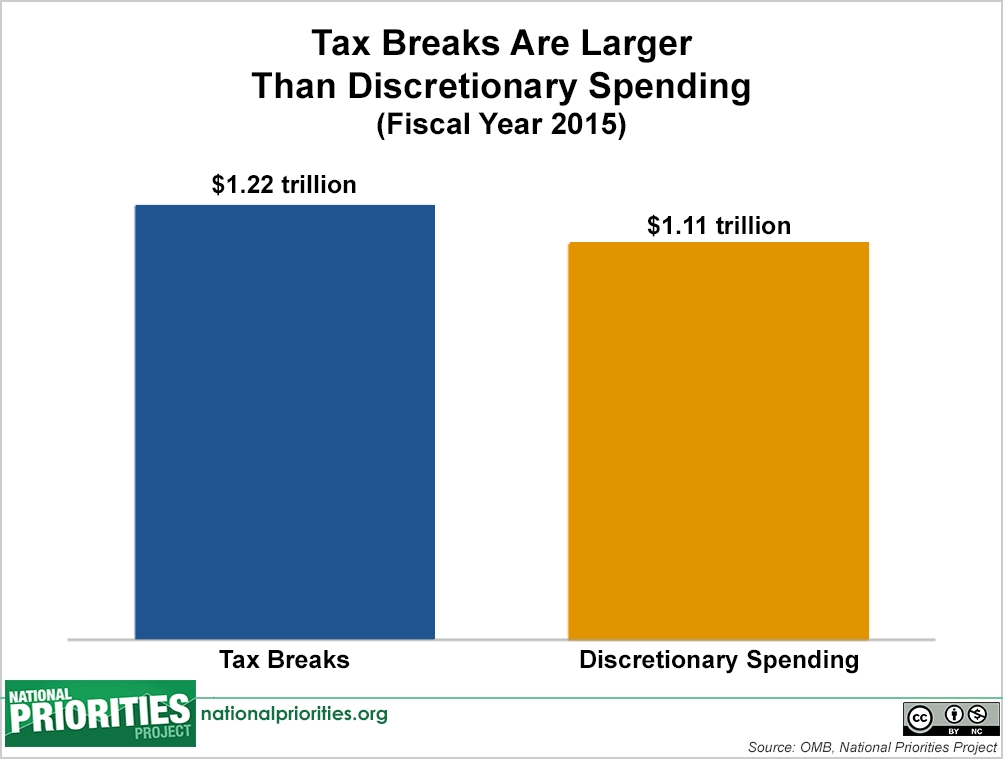

When the federal government spends money on mandatory and discretionary programs, the U.S. Treasury writes a check to pay the program costs. But there is another type of federal spending that operates a little differently. Lawmakers have written hundreds of tax breaks into the federal tax code – for instance, special low tax rates on capital gains, and a deduction for home mortgage interest – in order to promote certain activities they deem beneficial to society.

In fact, tax breaks function as a type of government spending, and they are officially called “tax expenditures” within the federal government. When the government issues a tax break, it chooses to give up tax revenue for a specific purpose – so both spending and tax breaks mean less money in the U.S. Treasury, and both reflect spending priorities laid out by Congress in various pieces of legislation. Tax breaks are expected to cost the federal government $1.22 trillion in 2015 – more than all discretionary spending in the same year.

Unlike discretionary spending, which must be approved by lawmakers each year during the appropriations process, tax breaks do not require annual approval. Once written into the tax code, they remain on the books until lawmakers modify them. That means that even when tax breaks fall short of, or outlive their original purpose intended by Congress, they frequently stay on the books.

Borrowing and the Federal Debt

If federal revenues and government spending are equal in a given fiscal year, then the government has a balanced budget. If revenues are greater than spending, the result is a surplus. But if government spending is greater than tax collections, the result is a deficit. The federal government then must borrow money to fund its deficit spending.

Deficit and Debt: What Are They?

While a deficit describes the relationship between spending and revenues in a single year, the federal debt – also referred to as the national debt – is the sum of all past deficits, minus the amount the federal government has since repaid. Every year in which the government runs a deficit, the money it borrows is added to the federal debt. If the government runs a surplus, it can use the extra money to pay down some of its debt. And each year, the government pays interest on the national debt as part of its overall spending.

As of June 4, 2015, total U.S. debt stood at $18.153 trillion.

Why Does the Federal Government Borrow?

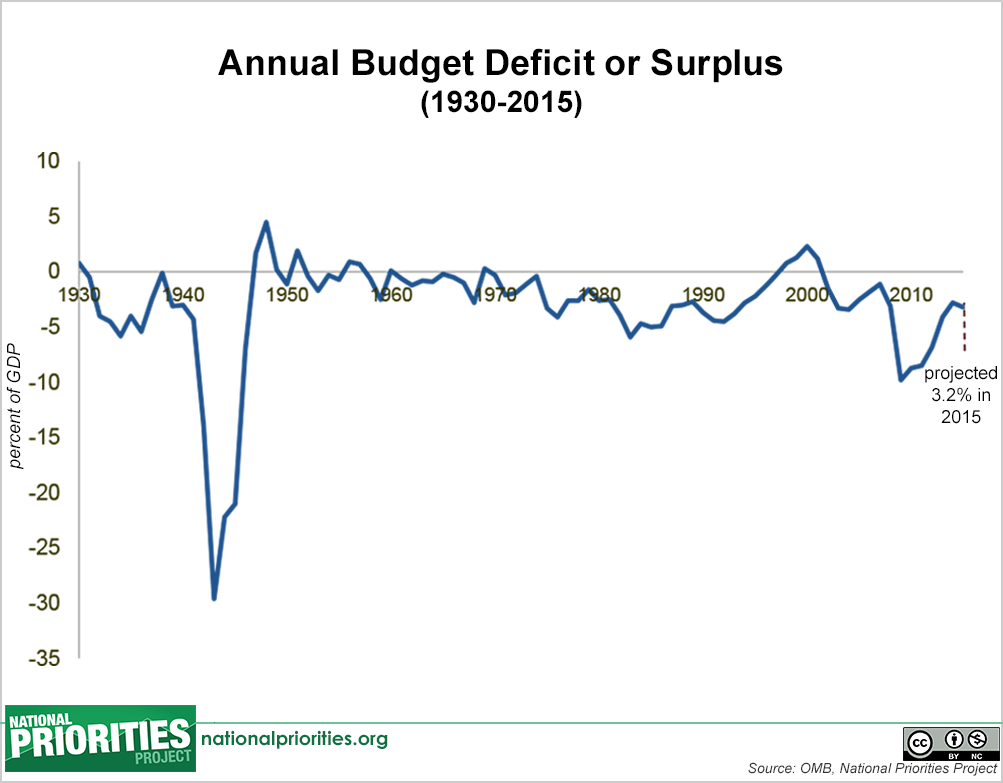

The federal government has run a deficit in 45 out of the last 50 years. Usually that deficit is around three percent of the economy, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

The size of a budget deficit in any given year is determined by two factors: the amount of money the government spends that year and the amount of revenues the government collects in taxes. Both of these factors are affected by the state of the economy, as well as by the tax and spending policies enacted by Congress.

For example, during tough economic times like the Great Recession, many types of government spending automatically increase because more people become eligible for need-based programs like food stamps and unemployment benefits. At the same time, tax revenues tend to decrease for a couple of reasons: people are working less, and paying less in taxes; and corporations also earn less profit, and they too pay less in taxes. What’s more, lawmakers may intentionally increase government spending during a recession in order to stimulate the economy, even though they know that one short-term result will be a deficit. During the Great Recession, the federal deficit in 2009 reached 9.8 percent of the economy, but in 2015 is about average again, at 3.2 percent of the economy.

The deficit can also reflect temporary spikes in spending that are not matched by equal spikes in revenue (through increasing taxes, for instance). For example, the deficit in 1943 at the height of war spending on World War II reached nearly 30 percent of the economy.

Finally, tax policy plays a major role in determining whether we run surpluses or deficits. Many factors probably contributed to the budget surpluses of the 1990s, but one of them was tax increases, which took the form of tax rate increases for the highest income taxpayers (although rates stayed well below what they had been prior to the 1980s). Likewise, major tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 were a major contributor to deficits over the last decade, and to today’s debt – by some measures, even more so than the economic downturn.

This line chart shows the size of the deficit or surplus in each fiscal year over much of the last century.

How Does the Federal Government Borrow?

To finance the debt, the U.S. Treasury sells bonds and other types of securities (Securities is a term for a variety of financial assets). Anyone can buy a bond or other Treasury security directly from the Treasury through its website, treasurydirect.gov, or from banks or brokers. When a person buys a Treasury bond, she effectively loans money to the federal government in exchange for repayment with interest at a later date.

Most Treasury bonds give the investor – the person who buys the bond – a pre-determined fixed interest rate. Generally, if you buy a bond, the price you pay is less than what the bond is worth. That means you hold onto the bond until it “matures.” A bond is mature on the date at which it is worth its face value. For example, you may buy a five-year $100 bond today and pay only $90. Then you hold it for five years, at which time it is worth $100. You also can sell the bond before it matures.

There are actually many different kinds of Treasury bonds, but the common thread between them is that they represent a loan to the Treasury, and therefore to the U.S. government.

Who Does the Federal Government Owe Money To?

The federal debt is the sum of the debt held by the public – that’s the money borrowed from regular people like you and from foreign countries – plus the debt held by federal accounts.

Debt held by federal accounts is the amount of money that the Treasury has borrowed from itself. That may sound funny, but recall from Where the Money Comes From that trust funds are federal tax revenues that can only be used for certain programs. When trust fund accounts run a surplus, the Treasury takes some of that surplus and uses it to pay for other kinds of federal spending. But that means the Treasury must pay that borrowed money back to the trust fund at a later date. That borrowed money is called “debt held by federal accounts;” that’s the money the Treasury effectively lends between different federal government accounts. Almost one-third of the federal debt is held by federal accounts, while the remaining two-thirds of the federal debt is held by the public.

Debt Held by the Public

Debt held by the public is the total amount the government owes to all of its creditors in the general public, not including its own federal government accounts. It includes debt held by American citizens, banks and financial institutions as well as people in foreign countries, foreign institutions and foreign governments.

As you can see in the pie chart above, about one third of the total federal debt, and nearly half of debt held by the public, is held internationally by foreign investors and central banks of other countries who buy our Treasury bonds as investments. These countries include China ($1.3 trillion), Japan ($1.2 trillion) and Brazil ($262 billion), the three countries that currently hold the most U.S. debt. Treasury also groups foreign holders of national debt by oil exporting nations (including Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Ecuador, Nigeria and others, $297 billion) and Caribbean banking centers (Bermuda, Cayman Islands, and others, $293 billion).18

The next largest portion of debt held by the public is held by private domestic investors, which includes regular Americans as well as institutions like private banks.

The U.S. Federal Reserve Bank and state and local governments also hold substantial shares of federal debt held by the public. The Federal Reserve’s share of the federal debt is not counted as debt held by federal accounts, because the Federal Reserve is considered independent of the federal government. The Federal Reserve buys and sells Treasury bonds as part of its work to control the money supply and set interest rates in the U.S. economy.

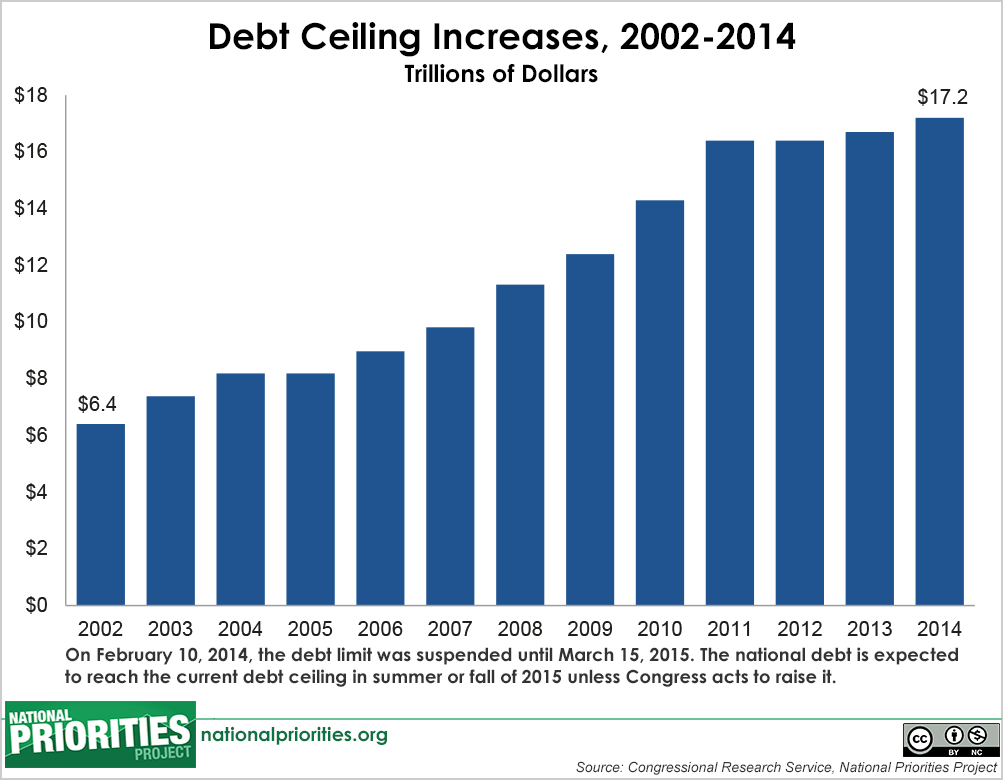

The Debt Ceiling

The debt ceiling is the legal limit set by Congress on the total amount that the U.S. Treasury can borrow. If the level of federal debt hits the debt ceiling, the government cannot legally borrow additional funds until Congress raising the debt ceiling, and could be left with no way to pay its bills. If this happens, it could result in sudden interruptions of government services and unintended consequences.

Congress has the legal authority to raise the debt ceiling as needed. Doing so does not authorize new spending, but rather allows the Treasury to pay the bills for spending that has already been authorized by Congress.

Why Is There a Debt Ceiling?

The debt ceiling evolved from restrictions that Congress placed on federal debt nearly from the founding of the country. Legislation that laid the groundwork for the current debt ceiling was passed in 1917, and the first overall debt ceiling was passed in 1939. Since then, the debt ceiling has been raised or otherwise amended more than 140 times, including more than a dozen times since 2000.

Often, the decision by Congress to raise the debt ceiling has not been controversial. Since 2011, however, due to political partisanship as well as debates about the size of the federal budget and deficit spending, the debt ceiling has become a highly contentious issue. Some members of Congress have pledged to allow the federal government to default on its debt payments rather than raise the debt ceiling again.

The Great Federal Debt Debate

There is an ongoing debate as to whether the government should limit its ability to borrow. Some consider deficit spending to be a hindrance to the government and the economy, arguing that a deficit only shifts the burden to future generations because it must be paid for eventually, just like any other loan.

Others see deficits as a crucial way for the government to stimulate the economy during an economic downturn. Proponents of this view believe that the role of government is not only to provide services that the private sector won’t, but also to stimulate the economy during economic crises. They argue that deficits are necessary in times of economic hardship, but that during economic booms, budget surpluses should be used to pay down the debt.

In some ways, deficits and debt are actually less controversial than you would think from listening to the rhetoric – with deficits in 45 out of the last 50 years, our government has chosen policies that lead to slight deficits more often than not, regardless of who controls Congress or the White House. And in times of surplus, lawmakers across the political spectrum have argued to use some of the surplus not just to pay down the debt, but for other priorities like government services or tax cuts.

Federal Budget Glossary

Actual Spending

Actual Spending is spending reported by the president after the end of a fiscal year. Actual spending is different from requested spending because it reflects the spending priorities approved by Congress during the annual appropriations process.

Appropriated Amount

Appropriated Amount (or appropriation) refers to the budget authority granted by Congress. (See also requested amount.)

Appropriation

Appropriation is a law that authorizes the expenditure of funds for a given purpose.

Appropriations Bill

A bill that specifies how much money can be spent on a given federal program. Reviewed by Appropriations subcommittees in both the House and Senate, appropriations bills must also be approved by the full House and Senate before being signed by the president to become law.

Appropriations Committees

Appropriations Committees in both the House and the Senate are responsible for determining the precise levels of budget authority for all discretionary programs.

Appropriations Process

The annual process through which Congress creates the discretionary budget.

Appropriations Subcommittees

Appropriations Subcommittees in both the House and the Senate, Appropriations subcommittees are committees made up of members of the full Appropriations Committee. Each of these subcommittees has jurisdiction over funding for a different area of the federal government. In both the House and Senate there are 12 different Appropriations subcommittees with the following areas of jurisdiction:

- Agriculture, Rural Development, and Food and Drug Administration

- Commerce, Justice, and Science

- Defense

- Energy and Water

- Financial Services and General Government

- Homeland Security

- Interior and Environment

- Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education

- Legislative Branch

- Military Construction and Veterans Affairs

- State and Foreign Operations

- Transportation, and Housing and Urban Development

Authorization Bill

An authorization bill gives a government agency the legal authority to fund and operate its programs. An authorization bill also sets maximum funding levels and includes policy guidelines. Government programs can be authorized on an annual, multi-year, or permanent basis. The specific amounts of money authorized in an authorization bill serve as limits on the amounts of money that subsequently may be appropriated by Congress, though lawmakers can choose to appropriate less than the amounts authorized.

Balanced Budget

Balanced Budget is a budget in which revenues and spending are equal in a given year.

Balanced Budget Amendment

An amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would require the federal government to enact a budget where expenditures do not exceed revenues in any fiscal year.

Budget Authority

Budget Authority is the federal government’s legal authority to spend a given amount of money for a certain purpose, according to laws passed by Congress and signed by the president.

Budget Control Act of 2011

The Budget Control Act of 2011 is legislation that passed in August 2011. It raised the debt ceiling, narrowly averting a debt crisis; placed caps on discretionary spending for 10 years; and set up an additional deficit reduction target to be achieved by a super committee or through automatic spending cuts known as sequestration.

Budget Resolution

A budget resolution is a non-binding resolution passed by both chambers of Congress that serves as a framework for budget decisions. It sets overall spending limits but does not decide funding for specific programs.

Chair’s Mark

The first draft of legislation introduced by the chair of a committee or subcommittee that is then debated and amended by committee colleagues. This ability to decide the starting point for all further work on a piece of legislation is an important part of the chair’s power.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

A Supreme Court case in which the court ruled that corporations and unions have the right under the First Amendment to express political views. This decision opened the door to a vast new role for private entities to influence elections, with no limits on the amount of money they spend to do so.

Conference

Conference refers to members of the House and Senate coming together to reconcile their two different versions of a given piece of legislation.

Conference Committee

Members of the House and Senate who work together to reconcile differences in their respective versions of a bill. Both the House and Senate must pass identical versions of any legislation before it can be signed into law by the President.

Conference Report

The final product of conference committee work, the report documents the changes made by conferees (i.e. what is taken out of which bill, etc).

Congressional Aide

Congressional aides are support staff for members of Congress. They perform a variety of tasks from administrative duties to keeping track of specific policy issues.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

The Congressional Budget Office is the non-partisan branch of Congress that provides analysis and materials related to the federal budget process, and objective analyses needed for economic and budgetary decisions related to programs covered by the federal budget.

Continuing Resolution (CR)

A Continuing Resolution is a piece of legislation that extends funding for federal agencies – typically at the same rate that they had been previously funded – into a new fiscal year until new appropriations bills become law.

Debt

Debt is money owed. Also see Federal Debt.

Debt Ceiling

The debt ceiling is the limit on the amount of debt the federal government allows itself to hold. Congress has the authority to raise the debt ceiling.

Debt Held by Federal Accounts

Debt Held by Federal Accountsis money the federal government borrows from itself. It results from the Treasury using surpluses from some accounts – for instance, Social Security – to buy Treasury bonds, and thus finance current government spending. Borrowed funds ultimately need to be repaid to the original account, with interest.

Deficit

Deficit is the amount by which government expenditures are greater than tax collections in a given year.

Direct Spending

See Mandatory Spending.

Disbursements

Actual payments made by the U.S. Treasury to recipients of a federal agency’s Obligations. Also see Outlays.

Discretionary Spending

Discretionary Spending is the portion of the budget that the president requests and Congress appropriates every year. It represents less than one-third of the total federal budget, while mandatory spending accounts for around two-thirds.

Earmarks

Earmarks are provisions added to legislation to designate money for a particular project, company, or organization, usually in the congressional district of the lawmaker who sponsored it. In 2010, the House of Representatives instituted rules to severely limit earmarks.

Effective Tax Rate

Effective Tax Rate is the percentage of income an individual or corporation actually pays in taxes. Effective tax rates often differ from official (also known as statutory or “marginal”) tax rates as a result of tax credits, deductions, or other provisions of the tax code.

Entitlement Programs

A term that refers to a certain kind of federal program in which all people who are eligible for the program’s benefits, according to eligibility rules written into law, must by law receive benefits if they apply for them. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), commonly known as food stamps, is an example of an entitlement program; anyone who qualifies and applies for benefits receives food stamps. Entitlement programs may also be referred to as earned benefit or social insurance programs.

Estate Taxes

Estate Taxes are taxes paid on an inheritance.

Excise Taxes

Excise Taxes are taxes placed on the sale of (usually) luxury items but also on specific consumer items like cigarettes, liquor, and gasoline.

Federal Debt

Federal Debt is the total of all past federal budget deficits, minus what the federal government has repaid.

Federal Funds

Federal Funds refers to tax revenue collected by the federal government for general purposes. These are distinct from trust funds, which are collected by the federal government for specific purposes, such as Social Security.

Federal Securities

Federal Securities are financial obligations, such as Treasury bonds, taken on by the federal government that require repayment at some point in the future.

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal Policy refers to decisions made by the federal government regarding government spending and taxation.

Fiscal Year

The federal fiscal year runs from Oct. 1 through Sept. 30. For example, fiscal year 2015 runs from Oct. 1, 2014, through Sept. 30, 2015.

Gift Taxes

Gift Taxes are taxes imposed on any transfer of property that occurs without payment.

Government Accountability Office (GAO)

The Government Accountability Office is an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for Congress. GAO operates as an auditor of the federal government, and investigates how the federal government spends taxpayer dollars. The head of GAO is the Comptroller General of the United States.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Gross Domestic Product is a way of measuring the size of a nation’s economy. It’s the total value of all final goods and services produced in an economy in a given year. “Final” means the value of goods and services purchased by the final consumer, as opposed to the value of raw materials purchased by a factory.

House Committee on the Budget

House Committee on the Budget is the committee in the U.S. House of Representatives that is responsible for writing a budget resolution, among other responsibilities. It became a standing committee with the passage of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

Income Security & Labor

Refers to programs like job training, disability, retirement, unemployment insurance and Social Security that promote employment and income security.

Inflation

Inflation is an increase in prices. Inflation occurs when the average price level across the economy – not just for a few goods – increases. So if the annual rate of inflation is 3 percent, then something you buy for $10 this year might cost $10.30 next year.

Interest on Debt

Interest on Debt is the interest payments the federal government makes on its accumulated debt, minus interest income received by the government for assets it owns.

Lobbying

Lobbying is the act of trying to influence lawmakers.

Mandatory Spending

Mandatory Spending is federal spending that is spent based on existing laws rather than the budgeting process. For instance, spending for Social Security is based on the eligibility rules for that program. Mandatory spending is not part of the annual appropriations process.

Marginal Tax Rate

The Marginal Tax Rate is the rate at which your last (highest) dollar of income is taxed. So, for example, if you are single and you make $22,000 per year, then your first $8,500 of income is taxed at a rate of 10 percent, and the rest of your income is taxed at 15 percent. In that case, 15 percent is your marginal tax rate.

Medicare

Medicare is a federal program that provides health care coverage for senior citizens and the disabled. It is funded through payroll taxes.

Monetary Policy

Monetary Policy refers to actions by the Federal Reserve to influence the supply of money in the economy as well as interest rates.

Multiplier Effect

The Multiplier Effect is an economics term for an increase in overall economic activity that is a consequence of an initial increase in spending. For example, if the government builds a new bridge in a small town, the increased incomes of those who work on the bridge will boost their spending at local stores, and the owners of those stores will then also see an increase in income as a result.

Net Federal Debt

Includes both debt and assets, and therefore appears smaller than the actual “Gross” debt.

Nominal

A nominal dollar amount is one that is not adjusted for inflation; it is the cost or value of something expressed as its price in the year it was purchased. For example, if in 1989 you paid $5 for a movie ticket, then the ticket’s nominal price is $5. Also see real.

Obligations

Obligations are binding financial agreements entered into by the federal government. Examples of obligations include contracts and the hiring of federal workers. Obligations are part of the process of federal spending. The federal budget creates budget authority to spend money for certain programs; then those programs enter into obligations to spend that money; and finally the Treasury spends the money, which is known as outlays.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB)

The Office of Management and Budget is part of the executive branch of government. OMB gives guidelines to federal agencies instructing them how to prepare their strategic plans and budgets. It also serves as the president’s accounting office.

Omnibus

An omnibus bill is a budget that encompasses all 12 appropriations bills into one bill, often used when Congress and the President can’t agree on passage of 12 individual spending bills.

Opportunity Cost

Opportunity Cost is what you give up when making a decision, measured in terms of the next best alternative.

Outlays

Outlays are money paid out by the U.S. Treasury; they occur when obligations are actually paid off, primarily by issuing checks or making electronic fund transfers.

Payroll Taxes

Payroll Taxes are taxes paid jointly by employers and employees to fund the Social Security and Medicare programs.

Per Capita

Per Capita means “per person.” For example, per capita GDP is GDP divided by population, which shows GDP on a per-person basis.

Poverty Line

Also called poverty level or the poverty threshold, the poverty line is determined by annual income. For example, the poverty line for a family of four was $22,113 in 2010; any family of four earning that amount or less was considered to be in poverty.

President’s Budget

The President’s Budget is the annual spending proposal, also known as the budget request, released by the White House each February. It represents the administration’s priorities as reflected in the specific funding requests of various federal agencies. It is the starting point for the annual budget process, but it is not legally binding.

Progressive

Progressive describes a tax system in which wealthier people pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than lower-income people. Progressive also describes political ideology on the left side of the political spectrum.

Real

A real number is a dollar amount that has been adjusted for inflation, whereas a nominal number has not.

Receipts

See Revenues.

Regressive

Regressive describes a tax system in which people earning lower incomes pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than their wealthier counterparts.

Request

The annual budget request is the president’s budget proposal to Congress, which is due, by law, on the first Monday of February each year for the coming fiscal year, which begins on Oct. 1. See also President’s Budget.

Requested Amount

Requested Amount refers to the amount requested by the president as part of the annual budget request at the start of the budget process.

Revenues

Revenues are funds flowing into the U.S. Treasury from such things as individual and corporate income taxes, payroll taxes and user fees (also referred to as receipts).

Senate Committee on the Budget

Senate Committee on the Budget is the committee in the U.S. Senate that is responsible for writing a budget resolution, among other responsibilities. It became a standing committee with the passage of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

Sequestration

Sequestration is the term for automatic, across-the-board spending cuts triggered by legislation limiting discretionary spending. Most recently, the Budget Control Act of 2011 included budget caps that went into effect in 2013 and will continue through 2021 unless Congress passes new legislation to stop them. If Congress does not abide by the spending caps during the appropriations process, spending will be automatically reduced through across-the-board, indiscriminate cuts known as sequestration.

Social Insurance

Social Insurance is made up of programs that help workers and their families replace part of income lost due to unemployment, disability, retirement, or death, as well as ensure access to adequate health care.

Social Security

Social Security, officially called the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, is a federal program that is meant to ensure that elderly and disabled people do not live in poverty. It is funded through payroll taxes.

Subsidy

Subsidy is direct assistance from the federal government to individuals or businesses for certain activities, which helps defray the costs of those activities.

Super Committee

The Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, known widely as the super committee, was created by the Budget Control Act of 2011. The super committee was comprised of six senators and six representatives evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans. They were tasked with finding a minimum of $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction to be implemented over 10 years. Because the super committee failed to complete this task by the established deadline of Nov. 23, 2011, across-the-board cuts known as sequestration went into effect.

Supplemental Appropriation

Supplemental Appropriation is legislation that provides funding beyond what was appropriated in the regular budget process. Congress typically passes supplemental appropriations in response to emergencies like a natural disaster.

Surplus

Surplus is the amount by which revenues exceed expenditures in the federal budget. The federal government has only run a surplus in four years in the last half century, from 1998 to 2001.

Trust Funds

Trust Funds are funds collected by the federal government for specific purposes, as designated by law. For example, payroll taxes are trust funds collected by the federal government to pay for the Social Security and Medicare programs.

Notes

- Office of Management and Budget Historical Table 1.2.

- US Const., art. 1, sec. 8, cl. 1

- Congressional Research Service, “Introduction to the Federal Budget Process,” Report 98-721, 3 Dec. 2012.

- Congressional Research Service, “Overview of the Authorization-Appropriations Process,” Report 20-731, 26 Nov. 2012.

- Congressional Research Service, “Mandatory Spending: Evolution and

- Growth Since 1962,” Report 33-074, 10 Mar. 2014.

- Congressional Research Service, “Introduction to the Federal Budget Process,” Report 98-721, 3 Dec. 2012.

- US Const., art.1, sec. 7, cl. 2

- Congressional Research Service, “The Congressional Budget Process: A Brief Overview,” Report 20-095, 22 Aug. 2011.

- Congressional Research Service, “The Congressional Budget Process: A Brief Overview,” Report 20-095, 22 Aug. 2011.

- Congressional Research Service, “The Appropriations Process: An Introduction,” Report 97-684, 22 Feb. 2007.

- Congressional Research Service, “The Congressional Budget Process: A Brief Overview,” Report 20-095, 22 Aug. 2011.

- Congressional Research Service, “Continuing Resolutions: Latest Action and Brief Overview of Recent Practices,” Report 30-343, 26 April 2011.

- Office of Management and Budget, Historical Table 1.2.

Office of Management and Budget, President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2016, Budget Authority. - Internal Revenue Service, “Data Book 2014”

- Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 542: Corporations,” 14 Nov. 2013.

- Citizens for Tax Justice, “The Sorry State of Corporate Taxes,” February 2014.

- U.S. Department of Treasury, “Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities.” April 2015 <http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Documents/mfh.txt>

Originally published by the Institute for Policy Studies, a program of Open Society Foundations, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.