The politically aware, digitally savvy and those more trusting of the news media fare better; Republicans and Democrats both influenced by political appeal of statements.

By (left-to-right) Amy Mitchell, Jeffrey Gottfried, Michael Barthel, and Nami Sumida / 06.18.2018

Mitchell: Director of Journalism Research

Gottfried: Senior Researcher

Barthel: Research Associate

Sumida: Research Analyst

Pew Research Center

In today’s fast-paced and complex information environment, news consumers must make rapid-fire judgments about how to internalize news-related statements – statements that often come in snippets and through pathways that provide little context. A new Pew Research Center survey of 5,035 U.S. adults examines a basic step in that process: whether members of the public can recognize news as factual – something that’s capable of being proved or disproved by objective evidence – or as an opinion that reflects the beliefs and values of whoever expressed it.

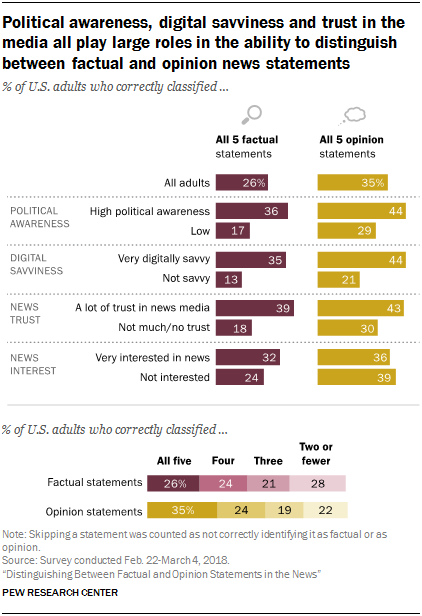

The findings from the survey, conducted between Feb. 22 and March 8, 2018, reveal that even this basic task presents a challenge. The main portion of the study, which measured the public’s ability to distinguish between five factual statements and five opinion statements, found that a majority of Americans correctly identified at least three of the five statements in each set. But this result is only a little better than random guesses. Far fewer Americans got all five correct, and roughly a quarter got most or all wrong. Even more revealing is that certain Americans do far better at parsing through this content than others. Those with high political awareness, those who are very digitally savvy and those who place high levels of trust in the news media are better able than others to accurately identify news-related statements as factual or opinion.

For example, 36% of Americans with high levels of political awareness (those who are knowledgeable about politics and regularly get political news) correctly identified all five factual news statements, compared with about half as many (17%) of those with low political awareness. Similarly, 44% of the very digitally savvy (those who are highly confident in using digital devices and regularly use the internet) identified all five opinion statements correctly versus 21% of those who are not as technologically savvy. And though political awareness and digital savviness are related to education in predictable ways, these relationships persist even when accounting for an individual’s education level.

Trust in those who do the reporting also matters in how that statement is interpreted. Almost four-in-ten Americans who have a lot of trust in the information from national news organizations (39%) correctly identified all five factual statements, compared with 18% of those who have not much or no trust. However, one other trait related to news habits – the public’s level of interest in news – does not show much difference.

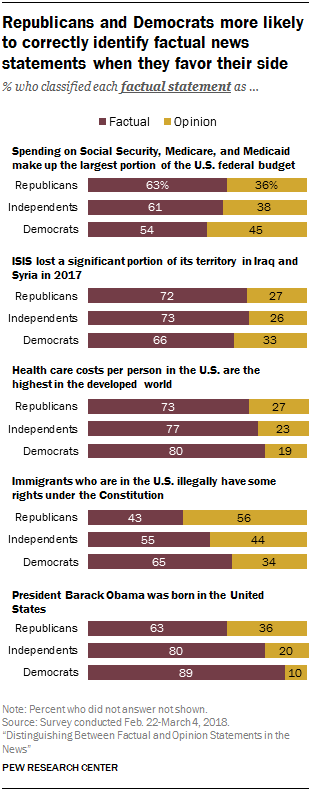

In addition to political awareness, party identification plays a role in how Americans differentiate between factual and opinion news statements. Both Republicans and Democrats show a propensity to be influenced by which side of the aisle a statement appeals to most. For example, members of each political party were more likely to label both factual and opinion statements as factual when they appealed more to their political side.

At this point, then, the U.S. is not completely detached from what is factual and what is not. But with the vast majority of Americans getting at least some news online, gaps across population groups in the ability to sort news correctly raise caution. Amid the massive array of content that flows through the digital space hourly, the brief dips into and out of news and the country’s heightened political divisiveness, the ability and motivation to quickly sort news correctly is all the more critical.

The differentiation between factual and opinion statements used in this study – the capacity to be proved or disproved by objective evidence – is commonly used by others as well, but may vary somewhat from how “facts” are sometimes discussed in debates – as statements that are true.1 While Americans’ sense of what is true and false is important, this study was not intended as a knowledge quiz of news content. Instead, this study was intended to explore whether the public sees distinctions between news that is based upon objective evidence and news that is not.

To accomplish this, respondents were shown a series of news-related statements in the main portion of the study: five factual statements, five opinions and two statements that don’t fit clearly into either the factual or opinion buckets – termed here as “borderline” statements. Respondents were asked to determine if each was a factual statement (whether accurate or not) or an opinion statement (whether agreed with or not). For more information on how statements were selected for the study, see below.

How the study asked Americans to classify factual versus opinion-based news statements

In the survey, respondents read a series of news statements and were asked to put each statement in one of two categories:

- A factual statement, regardless of whether it was accurate or inaccurate. In other words, they were to choose this classification if they thought that the statement could be proved or disproved based on objective evidence.

- An opinion statement, regardless of whether they agreed with the statement or not. In other words, they were to choose this classification if they thought that it was based on the values and beliefs of the journalist or the source making the statement, and could not definitively be proved or disproved based on objective evidence.

In the initial set, five statements were factual, five were opinion and two were in an ambiguous space between factual and opinion – referred to here as “borderline” statements. (All of the factual statements were accurate.) The statements were written and classified in consultation with experts both inside and outside Pew Research Center. The goal was to include an equal number of statements that would more likely appeal to the political right or to the political left, with an overall balance across statements. All of the statements related to policy issues and current events. The individual statements are listed in an expandable box at the end of this section, and the complete methodology, including further information on statement selection, classification, and political appeal, can be found here.

Republicans and Democrats are more likely to think news statements are factual when they appeal to their side – even if they are opinions

It’s important to explore what role political identification plays in how Americans decipher factual news statements from opinion news statements. To analyze this, the study aimed to include an equal number of statements that played to the sensitivities of each side, maintaining an overall ideological balance across statements.2

Overall, Republicans and Democrats were more likely to classify both factual and opinion statements as factual when they appealed most to their side. Consider, for example, the factual statement “President Barack Obama was born in the United States” – one that may be perceived as more congenial to the political left and less so to the political right. Nearly nine-in-ten Democrats (89%) correctly identified it as a factual statement, compared with 63% of Republicans. On the other hand, almost four-in-ten Democrats (37%) incorrectlyclassified the left-appealing opinion statement “Increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour is essential for the health of the U.S. economy” as factual, compared with about half as many Republicans (17%).3

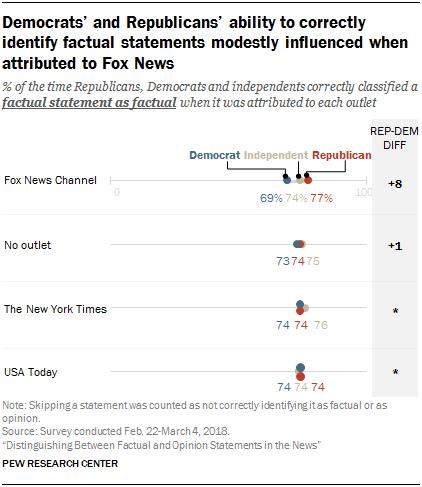

News brand labels in this study had a modest impact on separating factual statements from opinion

In a separate part of the study, respondents were shown eight different statements. But this time, most saw statements attributed to one of three specific news outlets: one with a left-leaning audience (The New York Times), one with a right-leaning audience (Fox News Channel) and one with a more mixed audience (USA Today).4

Overall, attributing the statements to news outlets had a limited impact on statement classification, except for one case: Republicans were modestly more likely than Democrats to accurately classify the three factual statements in this second set when they were attributed to Fox News – and correspondingly, Democrats were modestly less likely than Republicans to do so. Republicans correctly classified them 77% of the time when attributed to Fox News, 8 percentage points higher than Democrats, who did so 69% of the time.5 Members of the two parties were as likely as each other to correctly classify the factual statements when no source was attributed or when USA Today or The New York Times was attributed. Labeling statements with a news outlet had no impact on how Republicans or Democrats classified the opinion statements. And, overall, the same general findings about differences based on political awareness, digital savviness and trust also held true for this second set of statements.

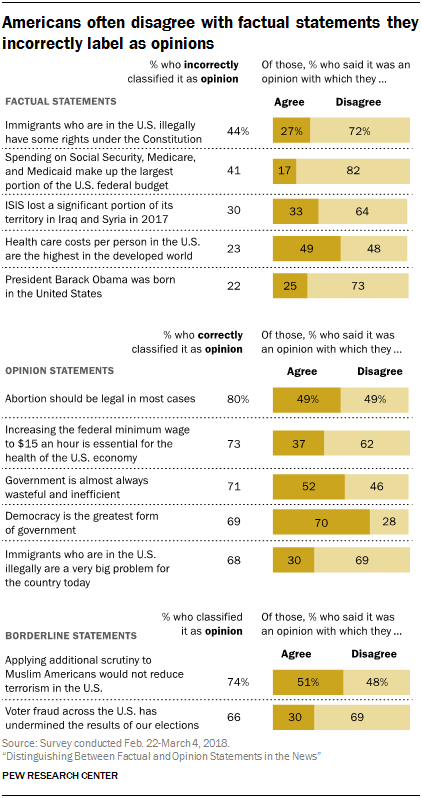

When Americans call a statement factual they overwhelmingly also think it is accurate; they tend to disagree with factual statements they incorrectly label as opinions

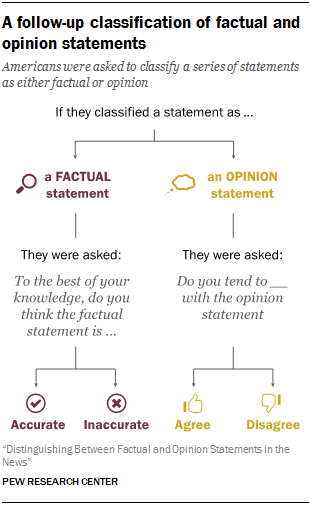

The study probed one step further for the initial set of 12 statements. If respondents identified a statement as factual, they were then asked if they thought it was accurate or inaccurate. If they identified a statement to be an opinion, they were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with it.

When Americans see a news statement as factual, they overwhelmingly also believe it to be accurate. This is true for both statements they correctly and incorrectly identified as factual, though small portions of the public did call statements both factual and inaccurate.

When Americans incorrectly classified factual statements as opinions, they most often disagreed with the statement. When correctly classifying opinions as such, however, Americans expressed more of a mix of agreeing and disagreeing with the statement.

About the study

Statement selection

This is Pew Research Center’s first step in understanding how people parse through information as factual or opinion. Creating the mix of statements was a multistep and rigorous process that incorporated a wide variety of viewpoints. First, researchers sifted through a number of different sources to create an initial pool of statements. The factual statements were drawn from sources including news organizations, government agencies, research organizations and fact-checking entities, and were verified by the research team as accurate. The opinion statements were adapted largely from public opinion survey questions. A final list of statements was created in consultation with Pew Research Center subject matter experts and an external board of advisers.

The goals were to:

- Pull together statements that range across a variety of policy areas and current events

- Strive for statements that were clearly factual and clearly opinion in nature (as well as some that combined both factual and opinion elements, referred to here as “borderline”)

- Include an equal number of statements that appealed to the right and left, maintaining an overall ideological balance

In the primary set of statements, respondents saw five factual, five opinion and two borderline statements. Factual statements that lend support to views held by more people on one side of the ideological spectrum (and fewer of those on the other side) were classified as appealing to the narrative of that side. Opinion statements were classified as appealing to one side if in recent surveys they were supported more by one political party than the other. Two of the statements (one factual and one opinion) were “neutral” and intended to appeal equally to the left and right.

How Pew Research Center asked respondents to categorize news statements as factual or opinion

As noted previously, respondents were first asked to classify each news statement as a factual statement or an opinion statement. Extensive testing of the question wording was conducted to ensure that respondents would not treat this task as asking if they agree with the statement or as a knowledge quiz. This is why, for instance, the question does not merely ask whether the statement is a factual or an opinion statement and instead includes explanatory language as follows: “Regardless of how knowledgeable you are about the topic, would you consider this statement to be a factual statement (whether you think it is accurate or not) OR an opinion statement (whether you agree with it or not)?”

After classifying each statement as factual or opinion, respondents were then asked one of two follow-up questions. If they classified a statement as factual, they were then asked if they thought the statement was accurate or inaccurate. If they classified it as an opinion, they were asked if they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

The Factual, Opinion, and Borderline Statements

Below are the 12 news statements that respondents were asked to categorize:

Factual statements

- Health care costs per person in the U.S. are the highest in the developed world

- President Barack Obama was born in the United States

- Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally have some rights under the Constitution

- ISIS lost a significant portion of its territory in Iraq and Syria in 2017

- Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget

Opinion statements

- Democracy is the greatest form of government

- Increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour is essential for the health of the U.S. economy

- Abortion should be legal in most cases

- Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally are a very big problem for the country today

- Government is almost always wasteful and inefficient

Borderline statements

- Applying additional scrutiny to Muslim Americans would not reduce terrorism in the U.S.

- Voter fraud across the U.S. has undermined the results of our elections

1. Overall, Americans identified more statements correctly than incorrectly, but sizable portions got most wrong

Americans are more likely than not to correctly distinguish factual statements from opinions, suggesting they have some proficiency in understanding the type of news content they see. But there is still a fair amount of misinterpretation.6

In this new study, a little over 5,000 U.S. adults were shown a mix of five factual and five opinion statements across a range of policy and current event topic areas. For each, they were asked to identify the statement as either factual – one that could be proved or disproved based on objective factual evidence – or as an opinion.

About a quarter of Americans (26%) correctly identified all five of the factual statements, while roughly the same percentage (28%) got no more than two correct. The largest portion (46%) answered three or four correctly. Overall, about three-quarters of Americans (72%) got more correct than incorrect – classifying at least three as factual.

A somewhat greater portion of Americans (35%) correctly identified all five of the opinion statements than did so with the factual statements. The largest portion again (43%) answered three or four correctly, while about two-in-ten (22%) misinterpreted most of the opinion statements as factual, classifying two or fewer as opinion. And, just like the factual statements, most Americans got more opinion statements correct than incorrect: About eight-in-ten (78%) correctly classified at least three of the five as opinions.

Some statements were correctly identified more often than others

Overall, Americans were reasonably adept at identifying each of the five factual and five opinion statements. For each statement, a majority correctly identified it as either factual or opinion. However, Americans tended to better identify some statements than others. Among the factual statements, about three-quarters of Americans (77%) correctly identified “President Barack Obama was born in the United States” and about the same portion (76%) correctly classified “Health care costs per person in the U.S. are the highest in the developed world” as factual. The two factual statements that the public had the most difficulty with were “Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget” and “Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally have some rights under the Constitution,” correctly labeled by just over half of respondents (57% and 54%, respectively).

Among the opinion statements, eight-in-ten Americans correctly identified “Abortion should be legal in most cases,” and around seven-in-ten correctly classified the other four opinion statements.

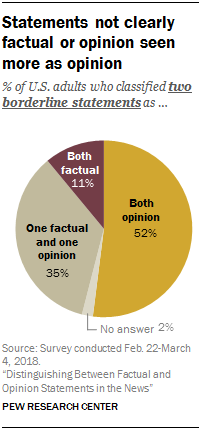

Most Americans classify statements that are not clearly factual or opinion as opinion

Not all news statements are unambiguously based in factual evidence or in a journalist’s or source’s beliefs, but rather fall somewhere in between the two. Statements that are in this murky space between factual statements and opinions – termed here as “borderline” statements – are more often treated by Americans as opinions.

In addition to the factual and opinion statements, respondents were asked to categorize two of these borderline statements. About half of Americans (52%) said both were opinions, compared with just 11% who said both were factual statements. About a third (35%) said one was factual and the other was opinion.

Looking at the individual statements, about three-quarters of Americans (74%) said “Applying additional scrutiny to Muslim Americans would not reduce terrorism in the U.S.” was an opinion, as did about two-thirds (66%) for “Voter fraud across the U.S. has undermined the results of our elections.”

While these two statements can be based in objective evidence (the factual element of the statement), the vague language – and in one case a prediction – makes these statements difficult to prove definitively (the opinion element of the statement). Thus, both of these were determined to be in this murky space between factual and opinion statements.

The statement “Applying additional scrutiny to Muslim Americans would not reduce terrorism in the U.S.” is predictive, and while evidence can be used to make an argument, it cannot be definitely proved or disproved because the results of such a policy in the U.S. are not yet known. For the second statement, “Voter fraud across the U.S. has undermined the results of our elections,” while there is a variety of evidence around the topic of voter fraud, the vagueness of the language of undermining election results makes it difficult to definitively show the relationship one way or the other.

2. The ability to classify statements as factual or opinion varies widely based on political awareness, digital savviness and trust in news media

Overall, some groups of Americans are far better at parsing through news content than others, suggesting gaps in the public’s competence. Most prominently, Americans’ familiarity with politics and the digital world bleeds into how they understand statements in the news. Those with high political awareness (those who are both knowledgeable about politics and regularly get political news) and high digital savviness (those who say they are highly capable of using digital devices and regularly use the internet) are much more likely to know the difference between factual and opinion news statements. Likewise, Americans with a lot of trust in national news organizations have an easier time separating factual from opinion statements than those with less trust. How closely one follows the news, on the other hand, provides only a modest edge in classifying factual statements, but not opinions.

Even though these characteristics relate in predictable ways to education, these relationships hold true even when accounting for level of education.7 Further, there is relatively modest overlap among the groups, meaning that each of these groups is distinct.8 For example, just 32% of those with high political awareness also have a lot of trust in national news organizations. The group that shows the largest overlap with the other groups is those who are very digitally savvy, since they account for a large portion of the population generally (48%), but even here the overlap with the other groups never reaches more than 58%.

Terminology

Political awareness is the measure of knowledge of and interest in politics and government and is based on the combined responses in two separate areas:

- Correctly answering three political knowledge questions (e.g., “Who is Mike Pence?”)

- Including government and politics among the topics one regularly gets news about

Those with high political awareness both answer all three knowledge questions correctly and regularly get news about government and politics; for those with moderate political awareness, only one of these two is the case; and for those with low political awareness, neither is the case.

Digital savviness is the measure of use of and familiarity with digital technology and is based on responses to two separate indicators:

- Reporting using the internet at least multiple times a day

- Being very confident in one’s ability to use electronic devices

Those who are very savvy both use the internet multiple times a day and are very confident in their ability to use digital devices; for those who are somewhat savvy, only one of these is the case; and for those who are not savvy, neither is the case.

Trust in news media is a measure based on the response to a single question: “How much, if at all, do you trust the information you get from national news organizations?” Respondents were divided into those who answered “a lot”; those who answered “some”; and those who answered either “not too much” or “none at all.”

News interest is a measure of interest in news more broadly and is based on the combined responses to two indicators:

- Following the news “most of the time, whether or not something important is happening” (rather than “only when something important is happening”)

- Responding that getting the news is one of the three activities, among a list of six, done most frequently during one’s free time

Those who are very interested both follow the news most of the time and list getting the news as one of their most frequent leisure activities; for those who are somewhat interested, only one of these two is the case; and for those who are not interested, neither is the case.

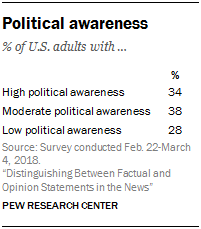

Those with high political awareness are far better able to identify factual and opinion statements

Those with high political awareness show far greater ability to correctly identify both factual and opinion statements. About a third (36%) correctly identified all five factual statements as factual, compared with 17% of those with low political awareness. Those with moderate awareness fell in between the two at 24%.

What’s more, just under half of those with low political awareness (45%) accurately classified two or fewer of the factual statements, misclassifying more than half of them. This was true of just 16% of those with high awareness.

A similar pattern emerges for correctly identifying all five of the opinion statements, which 44% of those with high political awareness, 29% of those with low awareness and 32% of those in between could do. The most politically aware were also more likely to see both borderline statements as opinions than those with moderate or low awareness, which is in line with people overall considering these statements to be opinions.

While some groups did fare better than others, overall, there was no group where a majority classified all five factual or opinion statements correctly.

In this study, political awareness measures how politically knowledgeable someone is and how often he or she gets news about government and politics. Those with high political awareness are both highly knowledgeable (accurately answering three political knowledge items) and report regularly getting political news. About a third of Americans (34%) have high political awareness, about four-in-ten (38%) have moderate awareness and 28% have low awareness.

Digitally savvy Americans fare far better at classifying factual and opinion statements

The very digitally savvy are also notably better at classifying statements as factual or opinion, with the divide between the very digitally savvy and those who are not savvy standing out as particularly stark. Roughly three times as many very digitally savvy (35%) as not savvy Americans (13%) classified all five factual statements correctly, with the somewhat savvy falling in between (20%). And about twice as many classified all five opinion statements correctly (44% of the very digitally savvy versus 21% of the not digitally savvy).

Like those with low political awareness, just under half of the not digitally savvy (45%) correctly classified two or fewer factual statements, erroneously identifying most as opinions. They were slightly more successful at the opinion statements, with around a third (34%) classifying two or fewer correctly.

Similar to those high in political awareness, those who are very digitally savvy were more likely to categorize both borderline statements as opinions than those who are less savvy.

Digital savviness is based on Americans’ frequency of internet use and confidence in using digital devices. About half (48%) are very digitally savvy (those who use the internet at least multiple times a day and are very confident in using digital devices), while 17% are not savvy (those who use the internet once a day or less and are not very confident in using digital devices). About a third (34%) fall in between the two and are categorized as somewhat digitally savvy.

Those with greater trust in the news media are more likely to correctly classify factual and opinion statements

Previous Pew Research Center findings that Americans’ attitudes about the news are strongly related to their news habits are reinforced in this study: Those more trusting of national news organizations are better at accurately categorizing factual and opinion statements.

About four-in-ten of those who have a lot of trust in the information from national news organizations (39%) categorized all five factual statements correctly, about twice the rate of those who have not much or no trust (18%) and also more than those with some trust (25%). Very similar gaps emerge for the opinion statements, declining from 43% among those with a lot of trust down to 30% among those with the least amount of trust. No differences surfaced for the borderline statements.

Likewise, looking at other news attitudes also measured in this survey, such as skepticism toward news and connection to news outlets, found that those who are less skeptical toward the news media were more likely to correctly classify both factual and opinion news statements. Respondents who feel a closer connection to their news outlets were more likely to correctly classify the factual statements.

Overall, about one-in-five U.S. adults (21%) has a lot of trust in the information they get from national news organizations, about half (49%) have some trust and 29% have not too much trust or none at all. And while Democrats are more likely than Republicans to trust the news media a lot (35% vs. 12%, respectively), the findings hold true even when accounting for party differences.

The role of education

While those with high political awareness, digital savviness and trust in national news organizations are overall more educated, the findings persist even when accounting for level of education.

As is often seen with survey measures of proficiency, Americans’ level of education makes a difference. Indeed, those with more education are more likely to classify factual and opinion statements correctly, with a magnitude of difference similar to that for political awareness and digital savviness. And given the differences between the very digitally savvy and those less so, it is not surprising that age matters as well, with those ages 18 to 49 being better at classifying statements than those ages 50 and older.9

Greater interest in news connects modestly to correct classifications of factual statements; no difference for opinions

In contrast to attitudes about the news, having greater interest in the news is not as closely related to deciphering factual from opinion statements.

Respondents who are the most interested in news were somewhat more likely to correctly identify the factual statements. About a third of the very interested (32%) correctly identified all five factual statements, compared with roughly a quarter of both the least interested (24%) and the somewhat interested (25%). These differences between the high and low groups are notably smaller than for political awareness, digital savviness or trust. And when it comes to opinion statements, there is no clear pattern.

Other measures of news interest asked about in the survey were also only weakly predictive of success in classifying statements. For instance, those who are highly engaged with the news by doing such things as writing letters to the editor, sharing news on social media or performing other actions with the news were more likely than those less engaged to correctly identify the factual statements. This was also true when comparing those who tend to put more consideration into their news (those saying they like to gather additional information about stories they see, debate the news with others and think about the news).

For this study, news interest is based on whether people follow news closely and get news in their free time. Nearly a quarter of Americans (23%) fall into the very interested group, which means they follow news most of the time and say news is one of the top three activities in their free time. About a third (32%) are not interested in news – they follow the news only when something important is happening and do not frequently get news in their free time. The greatest portion (44%) do one or the other but not both and are thus deemed “somewhat interested.”

3. Republicans and Democrats more likely to classify a news statement as factual if it favors their side – whether it is factual or opinion

In addition to past research that has shown stark differences between Republicans’ and Democrats’ trust of specific news outlets, the findings in this study go one step further, showing that those who identify with the two parties often differ in how they classify specific news content as factual or opinion.

Overall, majorities of both Republicans and Democrats correctly classified nearly all factual and opinion statements asked about. But Democrats were more likely to correctly classify a factual statement and to incorrectly classify an opinion as factual when it was more amenable to the left – and the same held for Republicans when the appeal was to the right. Some of these differences are quite large, with five of the 10 in the double digits.

As noted earlier, the goal was to include an equal number of statements in the study that would appeal to the sentiments of the left as of the right, maintaining an overall ideological balance. Even though most factual and opinion statements appealed more to either the left or the right, majorities of Republicans and Democrats correctly identified nearly all of them. There were only two instances across the factual and opinion statements in which no more than 50% of either party correctly classified them.

However, how large of a majority this was for each party often differed, sometimes substantially. Democrats were much more likely to correctly identify the two factual statements that were more favorable to the left. The statement “President Barack Obama was born in the United States” was classified as factual by 89% of Democrats, compared with 63% of Republicans. And “Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally have some rights under the Constitution” was classified as factual by 65% of Democrats versus 43% of Republicans.

Democrats were also somewhat more likely than Republicans to correctly identify one additional statement – one that was intended to appeal to both sides equally: “Health care costs per person in the U.S. are the highest in the developed world.” Eight-in-ten Democrats identified the statement as factual versus 73% of Republicans. This gap, though, was roughly a third as large as for the statements intended to be more favorable to the left.

To a lesser degree, the same pattern emerged – albeit with the parties reversed – for the factual statements that appealed more to the right. Republicans (63%) were somewhat more likely than Democrats (54%) to correctly identify “Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget” as factual. And 72% of Republicans, compared with 66% of Democrats, identified “ISIS lost a significant portion of its territory in Iraq and Syria in 2017” as factual.

Overall, there was a modest difference between the two parties in the portion who answered more correctly than incorrectly – but not of the same magnitude as between those with more or less political awareness, digital savviness and trust in the information from national news organizations. Across these five factual statements, 78% of Democrats answered at least three of the five correctly, compared with 68% of Republicans. However, it should be noted that this difference may be a function of the statements themselves. The factual statements appealing to one side may have been more divisive or provocative than those that appealed to the other side. In other words, these findings should not be taken to imply that one party is better able to classify factual statements than the other – but that the appeal seems to matter at least to a certain degree to both sides.

Members of both political parties are also more likely to incorrectly label opinion statements as factual when they are amenable to their side. Overall, some large divisions – up to 32 percentage points – emerge between both parties in identifying opinions.

Republicans were less likely than Democrats to correctly identify the two opinion statements that appeal more to the right. Nearly half of Republicans (49%) classified “Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally are a very big problem for the country today” as opinion versus 81% of Democrats, and “Government is almost always wasteful and inefficient” was classified as opinion by 67% of Republicans versus 75% of Democrats.

Likewise, Democrats were less likely to correctly identify the opinion statements amenable to the left. About six-in-ten Democrats (62%) classified “Increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour is essential to the health of the U.S. economy” as an opinion versus 83% of Republicans, while “Abortion should be legal in most cases” was classified as opinion by 74% of Democrats versus 87% of Republicans. The parties were on par in classifying “Democracy is the greatest form of government,” the statement intended to appeal equally to both sides, as an opinion, with 67% of Republicans and 64% of Democrats doing so.

With the two borderline statements, Republicans were more likely than Democrats to classify each as opinions. About eight-in-ten Republicans (82%) said that “Applying additional scrutiny to Muslim Americans would not reduce terrorism in the U.S.” is an opinion, compared with two-thirds of Democrats (67%). For the statement “Voter fraud across the U.S. has undermined the results of our elections,” Republicans were 7 percentage points more likely than Democrats to say it is an opinion (71% vs. 64%, respectively).

With a few exceptions, independents fell somewhere in between Republicans and Democrats in their classification of the 12 statements.

4. Americans overwhelmingly see statements they think are factual as accurate, mostly disagree with factual statements they incorrectly label as opinions

To understand what drives Americans to classify news as either factual or opinion, respondents were asked a follow-up question after each initial response. If they classified a statement as factual, respondents were asked if they thought it was accurate or inaccurate. An opinion classification was followed with a question asking if they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

Overall, Americans overwhelmingly tie the idea of news statements being factual with them also being accurate. This is consistent with how the term “facts” is sometimes used in modern political debate – statements that are true. Americans are far less likely to see factual statements as inaccurate – statements that can be disproved based on objective evidence. For both factual statements that people correctly classified and opinion statements that they incorrectly classified as factual, Americans were far more likely to have said each was accurate than inaccurate.

As for opinion statements, correct classifications are not necessarily associated with agreement, but instead result in a mix of agreement and disagreement. However, seeing factual statements as opinions largely coincides with disagreeing with them.

Statements classified as factual are almost always seen as accurate

On the whole, across the factual, opinion and borderline statements, large majorities of those who classified each as factual said it was accurate.

All five of the factual statements were accurate, so it makes sense that, overall, large majorities of those who classified each as factual thought it was accurate. For example, 91% of those who correctly identified the statement “Health care costs per person in the U.S. are the highest in the developed world” as factual said it was accurate.

Even when opinion statements were incorrectly classified as factual, large majorities again thought they were accurate, showing that misclassification links to people’s perceptions of their accuracy. At least eight-in-ten of those who identified each of the five opinions as factual statements also said it was accurate. For example, 92% of those who incorrectly classified “Democracy is the greatest form of government” as a factual statement said it was accurate. Likewise, those who classified each borderline statement as factual largely saw accuracy in each.

This does not mean, though, that the public does not ever see a claim in the news as factual and wrong – something that is stated as a fact, but can be unambiguously disproved by objective evidence. Segments of the public – albeit mostly small – classified statements as both factual and inaccurate. For example, a majority of those who correctly classified the statement “Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget” as a factual statement saw it as accurate (62%), but roughly four-in-ten (37%) thought it was inaccurate. While the findings do not address how Americans assess inaccurate statements since all of the factual statements included in the study were accurate, this study provides some evidence that Americans can see news as both factual and inaccurate.

Americans most often disagree with factual statements they incorrectly think are opinions

Dissent is a driving factor in why most Americans see factual statements as opinions. In the case of four of the five factual statements, each was largely disagreed with when incorrectly identified as an opinion. For example, 82% of those who incorrectly identified “Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget” as an opinion disagreed with it. There was a split between agreeing and disagreeing for only one of the five factual statements when incorrectly classified as an opinion.

There was more variation among correctly classified opinion statements. Americans who correctly classified the opinion statement “Democracy is the greatest form of government,” for instance, were more likely to agree (70%) than disagree with it (28%). On the other hand, those who said “Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally are a very big problem for the country today” were more likely to disagree (69%) than agree with it (30%).

Similar to the opinion statements, there was variation in agreement when borderline statements were classified as opinions. Nearly seven-in-ten (69%) of those who classified the statement “Voter fraud across the U.S. has undermined the results of our elections” as an opinion disagreed with it. However, those who classified “Applying additional scrutiny to Muslim Americans would not reduce terrorism in the U.S.” as an opinion were split between agreeing (51%) and disagreeing (48%).

5. Tying statements to news outlets had limited impact on Americans’ capacity to identify statements as factual or opinion

Given the strong partisan differences in the trust and use of various news outlets identified in the Center’s other research, this study separately examined the impact of adding news outlet attributions to factual and opinion statements. Overall, the attribution had a limited impact, except for one place: Republicans were modestly more likely than Democrats to accurately classify factual statements when they were attributed to Fox News Channel. But there was no influence of this news outlet between parties when it came to opinion or borderline statements.

For this part of the analysis, U.S. adults saw a mix of eight additional statements – three factual statements, three opinion statements and two borderline statements – all different from the first round of 12 statements discussed previously. One group – making up a quarter of respondents – was shown all eight statements attributed to no source, while a second group saw each statement randomly attributed to The New York Times (an outlet whose audience leans to the left), Fox News Channel (an outlet whose audience leans to the right) or USA Today (an outlet whose audience is more mixed). 10 The classification of these three outlets’ audiences is based on previously reported survey data, the same data that were used to classify audiences for a recent study about coverage of the Trump administration. For more detail on how this analysis was done.

Overall, as with the initial set of twelve statements, Republicans and Democrats were again more likely to label a claim as factual if it appealed to their side, regardless of outlet attribution.

The one instance in which the source label showed a modest influence on how members of both political parties categorized the factual statements was when the statements were attributed to Fox News Channel. While members of both parties accurately classified factual statements attributed to Fox News most of the time, Republicans did so to a greater degree (77% of the time), while Democrats did so to a lesser degree (69% of the time).11 Independents fell in between, identifying factual statements attributed to Fox News about three-quarters of the time (74%).

In contrast, Republicans and Democrats were about as likely to correctly identify the three factual statements when no outlet was attributed to them and when attributed to the two other outlets, The New York Times and USA Today. Furthermore, the attribution of any of the three outlets had no impact on Republicans’ or Democrats’ classifications of the opinion and borderline statements.

Though source attribution in this experiment had a minor impact on responses, other research has found strongly differing reactions to news outlets and widely diverging usage among Democrats and Republicans. So, it is important to keep in mind that this is one experiment within a larger study and that additional research could probe further into when news brands influence perceptions of the news and when they don’t.

Notes

- For example, fact-checking organizations have used this differentiation of a statement’s capacity to be proved or disproved as a way to determine whether a claim can be fact-checked and schools have used this approach to teach students to differentiate facts from opinions.

- A statement was considered to appeal to the left or the right based on whether it lent support to political views held by more on one side of the ideological spectrum than the other. Various sources were used to determine the appeal of each statement, including news stories, statements by elected officials, and recent polling.

- The findings in this study do not necessarily imply that one party is better able to correctly classify news statements as factual or opinion-based. Even though there were some differences between the parties (for instance, 78% of Democrats compared with 68% of Republicans who correctly classified at least three of five factual statements), the more meaningful finding is the tendency among both to be influenced by the possible political appeal of statements.

- The classification of these three outlets’ audiences is based on previously reported survey data, the same data that was used to classify audiences for a recent study about coverage of the Trump administration. For more detail on the classification of the three news outlets, as well as the selection and analysis of this second set of statements, see the Methodology. At the end of the survey, respondents who saw news statements attributed to the news outlets were told, “Please note that the statements that you were shown in this survey were part of an experiment and did not actually appear in news articles of the news organizations.”

- This analysis grouped together all of the times the 5,035 respondents saw a statement attributed to each of the outlets or no outlet at all. The results, then, are given as the “percent of the time” that respondents classified statements a given way when attributed to each outlet. For more details on what “percent of the time” means, see the Methodology.

- Research about the role of facts and opinions in the news has identified an increased blurring between the two, as well as increased opinion-based news coverage in recent years

- Level of education has a strong relationship of its own with how well Americans classify factual and opinion statements. But even though political awareness and digital savviness are related to education, education does not fully account for the relationship between these two factors and correctly identifying factual from opinions statements. Statistical analyses show that political awareness and digital savviness have an influence beyond that of education. In other words, among those at all levels of education, level of political awareness has an influence on their ability to correctly classify statements.

- See Appendix B for the overlap between each group.

- While digital savviness is associated with age, the relationship between digital savviness and correct classification persists even when accounting for age.

- At the end of the survey, respondents who saw news statements attributed to the news outlets were told, “Please note that the statements that you were shown in this survey were part of an experiment and did not actually appear in news articles of the news organizations.” Those who did not see the statements attributed to the outlets were told, “Please note that the statements that you were shown in this survey were part of an experiment and did not actually appear in news articles.”

- Since, due to the randomization, it was not possible to break up respondents into discrete groups by outlet attribution, this analysis grouped together all of the times the 5,035 respondents who saw a statement attributed to each of the outlets or no outlet at all. The results, then, are framed as the percent of the time that respondents classified statements a given way when attributed to each outlet. For more details on what “percent of the time” means.

Originally published by Pew Research Center, reprinted with permission for non-commercial, educational purposes.