For better or worse, politicians and entertainers dominated public life in America for much of the 20th century.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In November 1969, when Bob Hope asked the nation’s elected leaders to join him in celebrating a week of national unity no matter their political persuasion, one mayor, signing on, identified the period as “a time of crisis, greater today perhaps than since the Civil War.” The war in Vietnam, the counterculture, black power, and women’s liberation left the nation polarized between those who passionately protested the status quo and others who eagerly adopted the phrase popularized by President Nixon—“the silent majority”—to identify their adherence to traditional norms, mores, and values. Celebrities hoping to use their fame to publicize causes took on the roles of spokesperson and leader on each side of the divide as the worlds of politics and entertainment increasingly became interwoven.

I think humor is very significant in our American society today because, if there’s anything this country needs, it’s a few laughs. We certainly have the straight lines today, and the more dramatic side of our history, and I believe anything that can bring the people a little release is very, very important.

Bob Hope, 1967

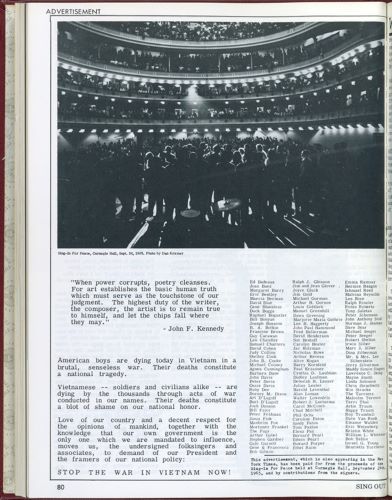

“Sing-In for Peace”

In 1965, as President Lyndon Johnson (1908–1973) escalated the war in Vietnam with bombing raids against North Vietnam and the introduction of ground forces, the anti-war movement coalesced. Drawing on tactics of the civil rights movement, folksinger Barbara Dane (b. 1927) and Sing Out! magazine editor Irwin Silber (1925–2010) organized a “Sing-In for Peace” at Carnegie Hall. To support their cause, the group took out an ad that quoted the late President Kennedy (1917–1963) on the civic need for unencumbered art.

Eartha Kitt and the Johnsons

During a White House luncheon of women discussing juvenile delinquency, Eartha Kitt (1927–2008) startled Lady Bird Johnson (1912–2007) by linking youth rebellion to the Vietnam War. The First Lady, in tears, acknowledged she had not “lived the background you have,” but stated that the war was no excuse not “to work for better things.” Earlier, Kitt questioned President Johnson (1908–1973) concerning working parents “too busy to look after their children.” The incident provoked disparate responses, including picketing by a women’s peace group.

“Radical Chic”

Leonard Bernstein suffered humiliation from the “radical chic” tag author Tom Wolfe applied to the Park Avenue penthouse gathering that Bernstein’s wife Felicia organized to raise money to defend Black Panthers who had been imprisoned with high bail. The Bernsteins received letters of support and outrage after a scathing New York Times editorial characterized the event as “elegant slumming.” Bernstein was compelled to issue a statement making it clear that while he and his wife did not support the actions of the Black Panthers, they did feel that their civil liberties should be defended. The accused Panthers ultimately were acquitted.

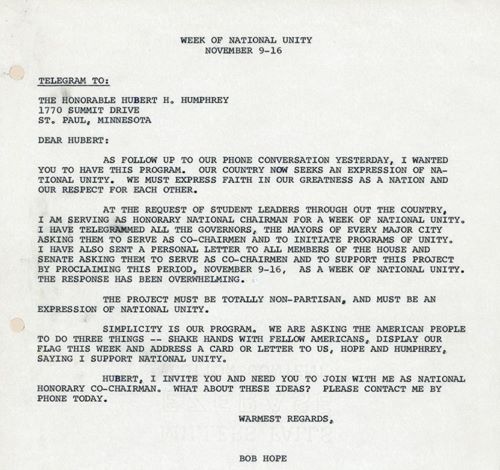

A Week of National Unity

In July 1941, defeated presidential candidate Wendell Wilkie (1892–1944) addressed crowds during National Unity Week, an initiative to bring together isolationists and interventionists. Twenty-eight years later, at the request of President Nixon (1913–1994), Bob Hope served as cochairman in a similarly titled effort in response to anti-war moratorium events that attracted millions nationwide. A Week of National Unity, aimed at the “silent majority,” occurred the same week as anti-war mobilization rallies that drew hundreds of thousands of demonstrators.

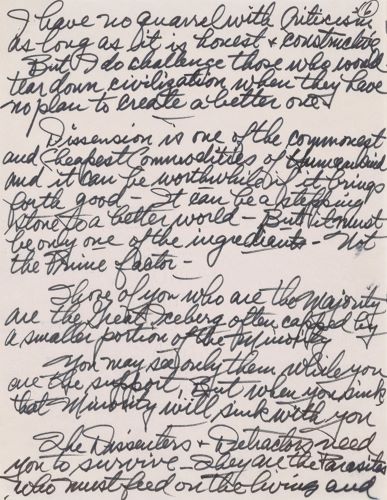

The “Silent Majority”

In a November 3, 1969, televised speech, President Nixon (1913–1994), referring to the recent escalation of anti-war protests, warned, “If a vocal minority, however fervent its cause, prevails over reason and the will of the majority, this nation has no future as a free society.” Nixon asked for support from “the great silent majority of my fellow Americans.” Bob Hope’s criticism of protesters and the media heartened those who identified themselves as part of the “silent majority.” Bob Hope’s views on dissent, expressed in these commencement speech notes, heartened those who identified themselves as part of the “silent majority.”

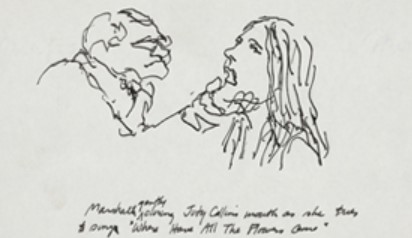

Entertainment at the “Chicago Seven” Trial

The trial of the “Chicago Seven”—activists indicted for conspiring to foment a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention—took on a circus atmosphere, with counterculture defendants confronting a contemptuous judge. When folksinger Judy Collins (b. 1939), on the witness stand, answered a question by singing “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” the judge ordered her to stop, saying “We are not here to be entertained.” Cartoonist Jules Feiffer (b. 1929), in the courtroom, captured the ensuing moment.

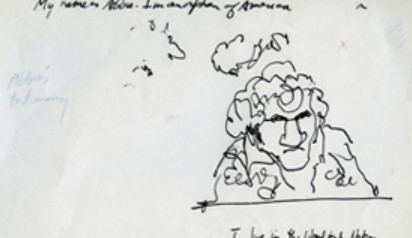

“I Live in the Woodstock Nation”

“Yippie” leader Abbie Hoffman (1936–1989), one of defendants known as the “Chicago Seven,” testified that he resided “in the Woodstock Nation,” and that as a “cultural revolutionary,” he meant to influence “inhabitants of a new nation and a new society through art and poetry, theater, and music.” Cartoonist Jules Feiffer (b. 1929), in the courtroom, captured Hoffman’s appearance.

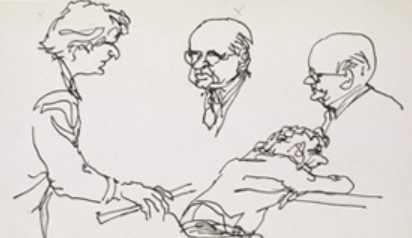

“Let the Record Show”

Cartoonist Jules Feiffer (b. 1929) matched incisive sketches of the Chicago Seven trial’s personages with ironic and iconic statements from the proceedings, some of which were provided by defendant Abbie Hoffman (1936–1989). Pictured here are Hoffman, slouched over, defense attorney Leonard Weinglass (1933–2011), at left, and Judge Julius Hoffman (1895–1983), who charged Weinglass and his colleague William Kunstler (1919–1995) with contempt.

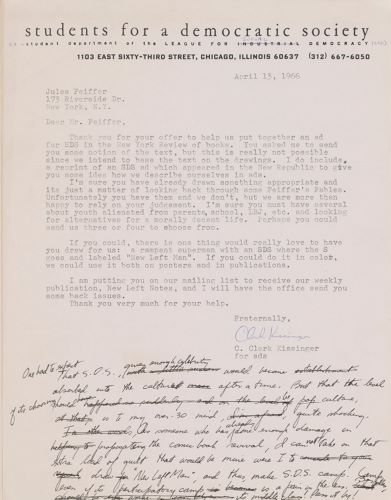

New Left Man

Formed in 1960, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) gradually gained followers with its emphasis on moral values, authenticity, and participatory democracy. With the escalation of the Vietnam War, membership began to increase dramatically. By 1966, the organization boasted some 15,000 members. In this letter, Clark Kissinger (b. 1940) of SDS’s national office asks Jules Feiffer (b. 1929) to help publicize the group further by drawing a Superman-like “New Left Man.” Feiffer, expressing an aversion to “camp,” declined the request.

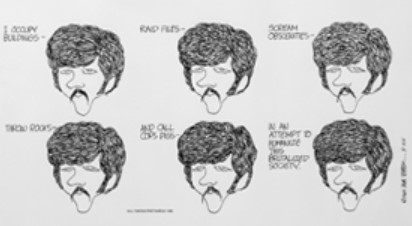

“An Attempt to Humanize This Brutalized Society”

Students were at the forefront of 1960s protests. Beginning with peaceful sit-ins in 1964 to protest restrictions on campus political activities, the language and actions of dissent turned violent as the war in Vietnam escalated. A Jules Feiffer (b. 1929) cartoon satirizing the hypocrisy of students who had occupied and trashed campus buildings during 1968 and 1969 provoked university administrators to write him and express their gratitude. Feiffer’s reply mixed solidarity with the protestors’ aims and criticism of their methods.

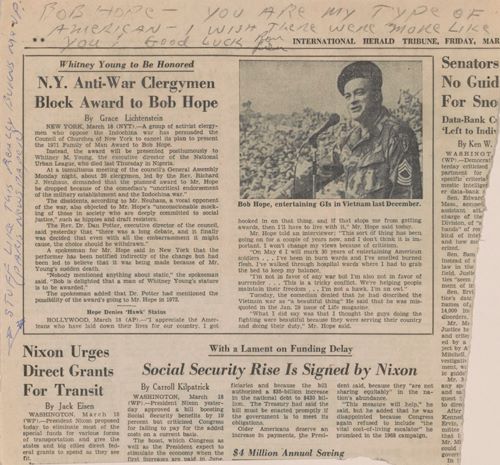

“I Won’t Change My Views Because of Criticism”

Bob Hope was chosen by the New York City Council of Churches board of directors to receive their 1971 Family of Man Award. “His life has been devoted to bringing laughter and good will on a world level, and among men in the armed forces,” they stated. The council’s general assembly, however, voted to rescind the honor, noting Hope’s “uncritical endorsement of the military establishment and the Indochina war.” Hope graciously supported the decision to bestow the award instead on deceased civil rights leader Whitney Young (1921–1971), but insisted, “I won’t change my views because of criticism.”

Political Vaudeville

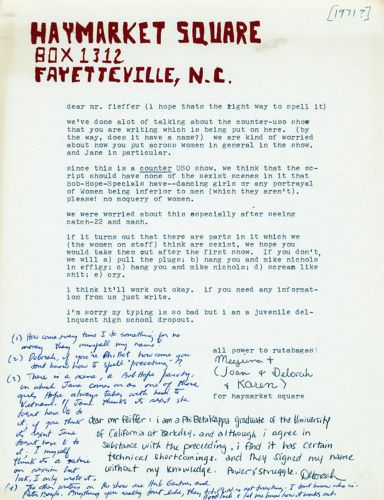

In 1971, Jane Fonda (b. 1937) headed a “political vaudeville” counter-USO troupe as part of the GI movement to encourage soldiers to refuse to fight. During the troupe’s first phase, they performed satirical skits by Jules Feiffer (b. 1929), Herb Gardner (1934–2003), and Peter Boyle (1935–2006) in GI coffeehouses, including Haymarket Square near Fort Bragg. By Christmas, the troupe re-formed with more women involved as “FTA”—standing for, among other things, “Free the Army”—and performed near military bases in Asia.

“Inoperative”

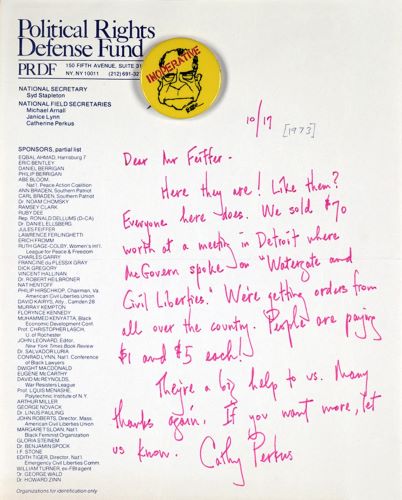

In April 1973, Nixon press secretary, Ronald Ziegler (1939–2003), announced that all the president’s previous statements about Watergate were “inoperative” and that “the President’s statement today,” which conflicted with earlier pronouncements, “is the operative statement.” That phrasing provoked satiric commentary. Bob Hope joked, “I’ve played golf with the President and he scores very well. Of course, every time he hits a bad shot he declares it ‘inoperative.’” A Jules Feiffer (b. 1929) button branded Nixon himself as “Inoperative.”

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress, 06.11.2010, to the public domain.