Hatshepsut is one of the most powerful female rulers of the ancient world, if not the most powerful one.

By Amina Šehović

Independent Historian

Introduction

Hatshepsut was among the most powerful women of the ancient world. Besides that, she was probably one of the most powerful women in the whole of human history. She was a ruler in ancient Egypt from ca. 1479 to 1458 BC. More precisely, Hatshepsut was a queen, a regent, a co-regent, and a king/pharaoh. Hatshepsut could not be the head of Egypt as a queen—in order to rule, she had to become a king or pharaoh. Because of that, she wanted to present herself not just as a woman, but as a man too. Ideology demanded a male ruler and Hatshepsut adjusted to that as best as she could. But Tutmos III erased her from history after her death with an act known as damnatio memoriae. Therefore, Hatshepsut’s name was forgotten for thousands of years. This paper will not deal in detail with Hatshepsut’s biography or all the achievements she accomplished during her reign, but through the prism of her life and reign, it will give a look at the model of women’s power in antiquity established by Hatshepsut, and a look at her position as a female ruler. One of the aspects of this paper is Hatshepsut’s visual representation, and an attempt will be made to explain what it means that Hatshepsut (in some cases) was portrayed as a man.

Who Was Hatshepsut?

Throughout history, women have often been invisible. Until recent times and the feminist movement, the position of women and their conception in historiography was completely different from the conception of men. Such was the case with women who were rulers. Hatshepsut, a woman pharaoh, is one of the most important figures in ancient history, but also in history in general. She is a woman who ruled Egypt, the world’s strongest power at the time, for twenty-two years as a very successful pharaoh. Yet Hatshepsut did not receive the attention of historiography and publicity that some other, much less successful rulers received.

Male rulers were celebrated for their successes, and their failures were attributed to the price of male ambition. Rulers who did something wrong or had interesting love affairs were given a place in historical narratives. Such is the case of Cleopatra—the most famous Egyptian woman. Hatshepsut had the “misfortune” to be an ancient female ruler who had a successful reign. Because of that, she attracted less attention than she should have. Ancient Egypt, this mystical and fascinating country, since ancient times represented something different for the Western world. The ancient Egyptian woman was viewed similarly—Hatshepsut, among others, was viewed in the same way.

In ancient Egypt, women had a better position than in the rest of the ancient world.1 Unlike other ancient societies, in Egypt women had a high degree of equal opportunity and freedom.2 Egyptian women from the royal family or the elite had a better position compared to women of the same rank from other parts of the ancient world. But to assume that this was the case with all the women of Egypt would be utopian and wrong.3

By the time Hatshepsut came to power as pharaoh, around 1473 BC,4 the Pyramids of Giza had existed for over 1,000 years and over seventeen centuries had passed since the country was first united under the legendary King Menes, around 3100 BC.5 Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thutmose I. Pharaoh Thutmose I came to power around 1504 BC, and before that he was a clerk in the army of Amenhotep I and a member of the Theban aristocracy.6 He was an extremely respected pharaoh, he fought wars for conquest and he gained the greatest scope for Egypt until then. With his Chief Wife Ahmose, Thutmose I had a daughter, Hatshepsut. His successor was Thutmose II, the son he had with a lower-ranking wife. The main wife of Thutmose II was his half-sister, Hatshepsut.7 The only child she had with Thutmose II was her daughter, Neferure. From an early age, Neferure was raised to play an important role in the family.8

Thutmose II, who was in poor health, came to power around 1492 and died around 1479 BC when power passed to his son Thutmose III, who was still quite young.9 On his behalf, his stepmother (and aunt) Hatshepsut ruled Egypt as regent, and at one point took power as a pharaoh and became a co-ruler with Thutmose III. Hatshepsut ruled for about 22 years, until 1458 BC, and the reign with Thutmose III lasted until 1425 BC.10 There are still debates about what happened to Hatshepsut in the end, whether she was killed by Thutmose III—although that is a less probable theory—, or whether she died a natural death.

After a long and successful reign, Hatshepsut suddenly disappears from all records. Her disappearance occurred after twenty-two years of rule as a regent and co-ruler, after which Thutmose III ruled for the next thirty-two years independently.11 Older historiography has assumed with some certainty that Thutmose III had her killed, because of his actions after her death—erasing her name and destroying her statues and monuments. However, the possible discovery of Hatshepsut mummy indicates that she most likely died a natural death. This seems more likely also because, if Thutmose III wanted to kill her, he could have done it earlier. In fact, there is no indication that Thutmose III killed her, although he erased her name from the monuments, destroyed her statues and walled up the obelisks—that is, he performed damnatio memoriae;12 and all this was done many years after Hatshepsut’s death, at the end of the reign of Tuthmose III.13

Hatshepsut is one of the most powerful female rulers of the ancient world, if not the most powerful one.14 Her reign was focused on building the Egyptian state from the inside.15 Before her, there were powerful women in Egypt, as well as women who ruled, but only for short periods of time. It is even more impressive that she gained power without bloodshed and without causing social trauma.16

The greatest achievements of Hatshepsut’s rule include construction projects, especially her funerary temple in Deir el-Bahri, and a trade expedition to the mystical land of Punt. Her reign was a combination of regency and co-rule.17 As extremely successful, Hatshepsut’s reign can be compared to the reigns of the most famous and successful female rulers in history. Other female rulers of antiquity ruled only in times of crisis, while Hatshepsut ruled in one of the most prosperous periods of ancient Egypt. As Kara Cooney said:

Hatshepsut’s greatest accomplishment and most daring innovation was her methodical and calculated creation of the only truly successful female kingship in the ancient world.18

Until modern nation-states, there were no women like Elizabeth I or Catherine the Great, women who had power for a long time.19 Theodora, Irena, Elizabeth, Maria Theresa, Catherine the Great, Victoria—these are all big names of famous rulers. Theodora is probably the most powerful woman in Byzantine history; Irena was regent and co-ruler of her son; Elizabeth was so powerful that the whole period she ruled was called the Elizabethan era; Maria Theresa was a key figure in 18th-century European political power; and Victoria gave name to one era, the Victorian era.20 Hatshepsut ruled thousands of years before any of them. She held her power at a time when being a woman meant being completely marginalized. When Hatshepsut is compared to another female ruler of Egypt, Cleopatra, Hatshepsut’s importance as a pharaoh becomes even more pronounced. Cleopatra used her intelligence, wealth, and charm to tie two powerful Romans to herself, but in the end, Egypt became just a Roman province. Cleopatra’s dynasty was destroyed, and Hatshepsut left her dynasty in a state of prosperity and power.21

Cleopatra VII is certainly better known to the wider masses than Hatshepsut, but Hatshepsut is still the most influential female pharaoh.22 Cleopatra was well educated, she spoke many languages and she was an ancient femme fatale.23 But when it came to rule, Hatshepsut was a much more successful ruler. Cleopatra has been attracting the attention of biographers since the time of her death, while Hatshepsut has been practically ignored by all but the most dedicated specialists.24 Similarly, Nefertiti became immortal because of her beautiful bust, her name became synonymous with beauty for the western world.25 And Hatshepsut? Although she is the most successful female pharaoh, she was considered irrelevant. Although she managed to rise in antiquity, in a male-dominated world, in many types of research in recent times she has been neglected because of her gender. Researchers viewed her as an evil stepmother, a usurper, an overly ambitious woman.

The Visual Representation of Hatshepsut – A Gender Issue

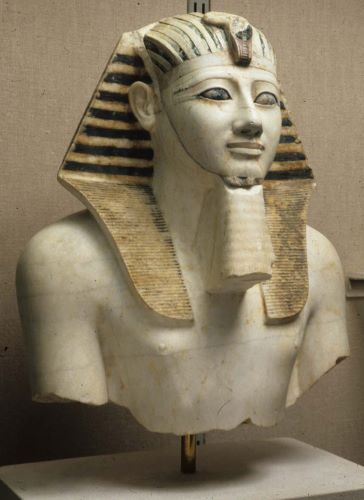

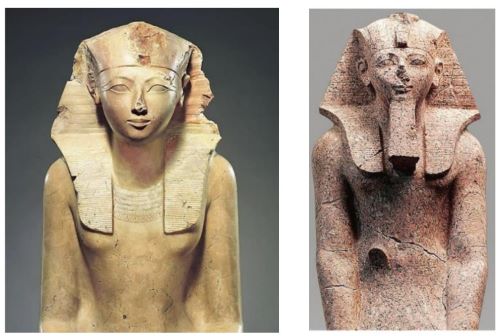

At the time when she was Queen, i.e. the wife of the King, Hatshepsut was depicted as a woman in paintings and statues, and the inscriptions from that time that mention her are in the female gender.26 During her regency, she began to be portrayed as a woman with some masculine attributes and regalia, as was the case with the female ruler of the earlier period, Sobekneferu.27 By the end of her regency, male attributes began to be predominant in her depictions, and at one point she began to be portrayed entirely as a man, with a male beard and a royal kilt.28 This is not overly strange, since, according to the mythological understanding, the pharaoh was Horus, the son of Osiris, and to be a real pharaoh, Hatshepsut had to be portrayed as a man.29 The representation of Hatshepsut as a man, therefore, arose from the canonical representation of the image of the pharaoh.30 In her representation in the royal role, she was able to take three groups as models: male pharaohs, royal mothers, and regent queens.31

During the early years of her regency, Hatshepsut presented herself as a traditional queen.32 It is possible that Hatshepsut began to fully present herself as a man in the seventh year of the reign of Thutmose III, that is, in the first year of their co-rule.33 Therefore, in ideology, she had to neglect her earlier marriage and career as a queen and turn to mythologizing of her predestination.34

While it is clear that Hatshepsut portrayed herself as a man to prove her legitimacy, scholars have questioned whether she actually saw herself as a woman or as a man. Consequently, one of them, Edward L. Margetts, considered that Hatshepsut identified with her father, and that she hated her husband and stepson, and that this hatred of her husband was proof that she had adapted poorly to heterosexual marriage, and also stated that one could speculate about her transvestism.35 Margetts is one of the older historiographers who observed the relations between Hatshepsut and the three Thutmoses in one dimension, and he drew conclusions based on that. Indeed, it is not known what the marriage of Thutmose II and Hatshepsut was like; perhaps it was full of hatred or perhaps full of love, so this marriage cannot be used as legitimate evidence of what Hatshepsut was. It is undeniable that the official image of Hatshepsut has evolved from a purely feminine to a definitively masculine iconography; there is also no doubt about the real femininity of Hatshepsut—she was the wife of Thutmose II and the mother of Neferure.36 She used both male and female royal titles; the female ones are: Daughter of Ra, Female Horus, and Perfect Goddess.37

The fact that Hatshepsut did not plan to hide her feminine side can be seen by the fact that, in inscriptions, she sometimes presented herself in the feminine gender.38 Uroš Matić explains that this presentation of Hatshepsut enabled her to be a pharaoh, regardless of what her body was.39 Several other rulers in Egypt’s New Kingdom exhibited non-binary gender identities, such as Queen Tiye, Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and Tawosret. Hatshepsut was just one example of an era of people who enjoyed playing with complex images.40

Not all frameworks of people from antiquity can be classified in today’s taxonomy. If Hatshepsut is viewed without the established framework of the new age, she was the woman who chose to present herself as a man because of political, religious, social, and ritual contexts.41 Apparently, she did not think that her presentation was limited to only two genders, but she had creative alternatives, combining attributes to show herself as a former queen, current king, and divine protector of Egypt.42 One of the researchers, Diamond, believes that Hatshepsut’s public performance was understandable to the ancient Egyptians, because they believed in hermaphroditic deities, as well as post-mortem gender fluidity.43 Hatshepsut was not an anomaly for them, as it is considered today.44

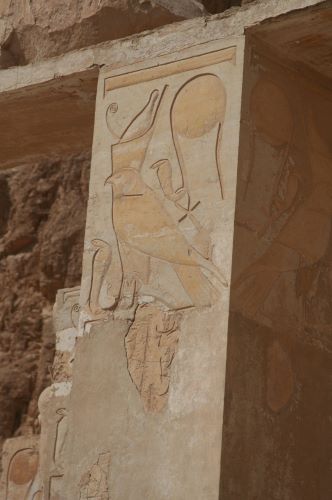

Variations of the gender in which Hatshepsut’s inscriptions were written are visible and could have been caused by political and ritual reasons.45 Hatshepsut could not be at the top of Egypt as a queen—in order to rule, she had to become a king or pharaoh.46 Perhaps Hatshepsut saw herself as an androgenic being, modeled on the god Atum, who could play both male and female roles when needed to ensure the vitality and maintain the stability of the kingdom.47 When Thutmose III destroyed the statues and inscriptions of Hatshepsut, he destroyed only those which refer to her as a pharaoh.48

Virginia Laporta points out that the alteration of Hatshepsut’s depiction served to alter the image she wanted to send—the queen became king, both figuratively and literally.49 As Egyptian society was largely illiterate, it was more important to portray oneself as a pharaoh, i.e. a man, in paintings and statues rather than inscriptions. Statues from Deir el-Bahra and other temples reflect Hatshepsut’s change from woman to man and the full acceptance of royal iconography.50 All the evidence suggests that her visual transformation into a man was a process, not an event that happened all at once.51 As there is no mention of Hatshepsut’s transformation in ancient texts, only images of change remain to tell the story.180 Ideology demanded a male ruler. Hatshepsut adjusted to that as best as she could.52

Conclusion

Hatshepsut’s life was unusual, to say the least. She was a powerful woman in a world created for men. A woman who dared to be a pharaoh, a woman who dared to be important as a man at a time when that was hard to imagine. Although her life is inextricably linked with the three Thutmoses, Hatshepsut was not subordinated, but stood at the head of the state, side by side with Thutmose III, one of the greatest pharaohs; and in the earlier period, when she ruled for him as regent, she made decisions independently. She adapted to the world of men as best as she could, portraying herself as a pharaoh, but not forgetting her feminine characteristics either.

This great woman-pharaoh is not represented in historiography, nor the public as much as she should be. But, truth be told, the study of her life is also hampered by the lack of sources that are not mythologized or embellished. If there were some records of her daily life, albeit distorted ones, it would be easier to imagine her as a person of flesh and blood and write books and articles. Since that is not the case, all that is known about Hatshepsut’s childhood, marriage, motherhood is a public version written on the walls of temples, shown in paintings and statues. As these public versions of ancient Egyptian history were embellished and never portrayed intriguing or personal details of life through the sources, only the outlines of her silhouette are visible; only what she was to the public. Nothing personal, nothing human is contained in it.

Women who held real political and military power in antiquity can be counted on fingers of one hand—these are women like Cleopatra and Hatshepsut, Budika, and Empress Lou. Historiographical perspectives on female rulers and male rulers have changed over time. Older historiography has more often looked suspiciously at female rulers than at male rulers, which is changing in recent times. Nevertheless, recent historiography is sometimes known to follow some historiographical misconceptions designated by earlier researchers.

If Hatshepsut had been born as a man, her long reign would have almost certainly been remembered for her great achievements. Instead, Hatshepsut’s gender became her most important characteristic, and historians have concentrated more on attempts to revive the intrigues that brought her to the throne, the intrigues that kept her on it, and alleged love affairs. In short, instead of appreciating her great achievements, those achievements have long been overshadowed by the soap opera that some historians have made of Hatshepsut’s life.

Hatshepsut is neither the first woman to rule Egypt nor the most famous. It is true that a few women were at the head of ancient Egypt, but Hatshepsut was not the only one. However, she is the only one that ruled Egypt in a non-crisis period and the fact is that her rule was by far the most successful rule of a woman in antiquity, which is why she deserves more attention than she receives.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Although they had a secondary position in relation to men. Nelson Pierrotti, “El rol de la mujer en el Egipto faraónico. ¿Qué oportunidades tuvo en la vida social, política y religiosa?” in Clio. Revista de Historia 15, (2016), 8.

- Khalil, Ahmed A. Moustafa, Marie Z. Moftah, Ahmed A. Karim, „How Knowledge of Ancient Egyptian Women Can Influence Today’s Gender Role: Does History Matter in Gender Psychology?“ in Frontiers in Psychology, 7, (2016).

- Gay Robins, Las mujeres en el Antiguo Egipto, (Madrid: Akal Ediciones, 1996), 11, 20; In addition to having a better position, the main purpose of women was to marry and have children. Barbara Watterson, Women in Ancient Egypt, (Glucesteshire: Amberly publishing, 2013).

- Hatshepsut came to power as regent around 1479 BC, and as pharaoh in 1473 BC. The chronology of Egyptian dynasties and individual pharaohs is not something that all Egyptologists agree on. The chronology used in this paper is one that has been accepted by most scholars. The chronology of the Eighteenth Dynasty is taken from: Catharine H. Roehrig, “Introduction” in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, 2-6, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 6.

- Roehrig, „Introduction“, 3.

- Ibidem.

- Nicolas Grimal, Historia del antiguo Egipto, (Madrid: Acal S. A., 1996) 294. In ancient Egypt, it was customary for pharaoh to marry his sisters so that the blood of the heir to the throne would be pure. Also, pharaoh had more than one wife.

- Zbigniew E Szafrański: „The Exceptional Creativity of Hatshepsut“ in Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut, ed. Jose M. Galan, Betsy M. Bryan and Peter F. Dorman, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014), 133.

- Mladen Tomorad: Staroegipatska civilizacija sv. 1: Povijest i kultura starog Egipta, (Zagreb: Sveučilište u Zagrebu – Hrvatski studij, 2016), 79.

- Roehrig, “Introduction”, 6.

- Lisa Sabbahy: „Queens, Pharaonic Egypt“ in The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, First edition, ed. Roger S. Bagnall, Kai Brodersen, Craige B. Champion, Andrew Erskine, Sabine R. Huebner, (West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing, 2013), 5708.

- For the ancient Egyptians, deleting names and characters from monuments, destroying statues and any mention of a dead person did not mean that person was only erased from history – it also meant denying that person the afterlife. That destruction is what is termed damnatio memoriae. After Hatshepsut’s death, her name was erased or changed on most monuments. Damnatio memoriae over Hatshepsut was executed by Thutmose III – he destroyed the statues with her image, changed their purpose, deleted her depictions and names. (Kara Cooney: When Women Ruled the World, Six Queens of Egypt, (National Geographic, 2018), 294.; Virginia Laporta: „La figura regina de Hatshepsut: una propuesta de análisis a partir de tres cambios ontológicos“ in Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 10, (2012), 108.; M. R. Bunson: The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, (New York: Gramercy Books, 1999), 161.) Damnatio memoriae is a very severe punishment inflicted on a dead pharaoh by destroying his paintings and other depictions. It was believed that the dead lived in their paintings on earth and in that way had eternal life. Joyce Tyldesley: Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt, (London, 1994), 229.

- Dylan Bickerstaff: „The Burial of Hatshepsut“ in Heritage of Egypt 1, (2008), 3-14.

- The only rivals to Hatshepsut’s model of female power in antiquity will come from later imperial China. Cooney, The Woman Who Would Be King, 317.

- Grga Novak: Egipat: prethistorija, faraoni, osvajači, kultura, (Zagreb, 1967), 136.

- Kara Cooney, The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt, (New York: Crown, 2014), 20.

- Grimal, Historia del antiguo Egipto, 296.

- Cooney, The Woman Who Would Be King, 317.

- Ibidem.

- Kathleen Kuper ed.: The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people, The 100 most influential women of all time, (New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, 2010), 36, 42, 89, 110, 159.

- Cooney, The Woman Who Would Be King, 317.

- Ann Macy Roth: „Models of authority Hatshepsut’s Predecessors in Power“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, 9-15, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005, 12.

- Kuper, The Britannica guide 25.

- Tyldesley, Daughters of Isis 225.

- Ibidem.

- Kristina Hilliard and Kate Wurtzel: „Power and Gender in Ancient Egypt: The Case of Hatshepsut“ in Art Education 62, no. 3, (2009), 26.

- Sabbahy, „Queens, Pharaonic Egypt“, 5708. The second female pharaoh in the history of Egypt, or the first certain female ruler, was Sobekneferu, whose name translates as the beauty of Sobek. Sobekneferu was probably the model for Hatshepsut 300 years later. She ruled as the pharaoh of Egypt after the death of her brother and husband Amenemhat IV, and her reign lasted almost four years. (Kim S. B Ryholt,: The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 BCE (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997), 185; Betsy M Bryan: „The temple of Mut: New Evidence on Hatshepsut’s Building Activity“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 294.); V. G. Callender says: It is clear (…) that Sobeknefer provided a number of models that Hatshepsut later imitated and developed in her own efforts to establish herself as a pharaoh. (Dimitri Laboury: „How and Why Did Hatshepsut Invent the Image of Her Royal Power?“ in Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut, ed. Jose M. Galan, Betsy M. Bryan and Peter F. Dorman, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014), 87).

- Hilliard and Wurtzel, „Power and Gender“, 25.

- Sabbahy, “Queens, Pharaonic Egypt“, 5708; During lifetime, the pharaoh identified with Horus, and after his death, according to Egyptian belief, the pharaoh turned into Osiris. Horus is one of the most significant ancient Egyptian deities who served many functions, most notable god of kingship and the sky. Osiris is the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation (Luis Tomas Melgar Valero,: Mitovi sveta, (Beograd: Laguna, 2017), 102).

- Hilliard and Wurtzel, „Power and Gender“ 26.

- Macy Roth, „Models of authority Hatshepsut’s Predcessors“ 9.

- Peter F Dorman: „Hatshepsut Princess to Queen to Co-Ruler“, Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dryfus and Cathleen A. Keller, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 88.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem; Hatshepsut’s view of her own divinity was centered around god Amon — she claimed she was Amon’s son/daughter. On the wall of the temple in Deir-el-Bahri, she had the course of her birth written down, claiming that her mother had conceived her with the god Amon and that she was a deity. (James P. Allen: „The role of Amun“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 85).

- E. L. Margetts: „THE MASCULINE CHARACTER OF HATSHEPSUT, QUEEN OF EGYPT“, in Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 25, No. 6, (1951), 561.

- Laboury, „How and Why Did Hatshepsut Invent the Image“, 50.

- Kelly-Anne Diamond: „Hatshepsut: Transcending Gender in Ancient Egypt“, in Gender & History, Vol. 32 No. 1, (2020), 178.

- Dorman, „Hatshepsut Princess to Queen“, 88.

- Uroš Matić: „(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal“ in Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 23(3), (2016), 19.

- Diamond, „Hatshepsut: Transcending Gender“ 169; Hatshepsut’s earliest performances in the Djeser djeseru (the name of her temple in Deir el-Bahri) show how she combined male and female characteristics. On the statues of Osiris, she is depicted as a man or Osiris, but if it is looked closely it can be seen the female elements on the earliest statues: the skin color was yellowish as traditionally depicted a woman from the royal family, not deep red as ocher, as men. Facial features were more feminine than masculine. This combination of fine female lines on the Osirisids does not seem to have received support, so Hatshepsut masculinized a new series of depictions of the Osirisids in Deir el-Bahri. The faces got a new, masculine shape with a stronger jaw, nose and eyebrows. The statues are painted with both yellow and red pigment, resulting in atypical orange skin color. (Cooney, The Woman Who Would be King 227, 228).

- Kristen Gylros „A Royal Queer: Hatshepsut and Gender Construction in Ancient Egypt“ in Shift, 8, (2015). Cathleen A.Keller: „The statuary of Hatshepsut“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 49.

- Ibidem, 52. If we look at all aspects of life in ancient Egypt, it is clear that gender did not include two discrete categories, especially when considering the concept of kingship and posthumous traditions.

- In Egypt’s New Kingdom, it was believed that royal women underwent postmortem sexual transformation to facilitate their rebirth in the afterlife. This phenomenon further points to the fluidity of gender in ancient Egypt. Diamond, „Hatshepsut: Transcending Gender“, 176.

- Diamond: „Hatshepsut: Transcending Gender“, 169.

- Laporta, „La figura regina de Hatshepsut“, 92.

- Ibidem, 70.

- Gylors, „A Royal Queer:“, 56.

- Tyldesley, Daughters of Isis, 267.

- Laporta, „La figura regina de Hatshepsut”, 14.

- Cathleen A.Keller: „The statuary of Hatshepsut“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 158.

- Cooney, The Woman Who Would be King, 228.

- Ibidem, 229.

- “Hatshepsut was broadcasting different messages to different sets of people. To those elites who could read hieroglyphic text and participate in complex theological discourse, she presented the full complexity of gender-ambiguous kingship. There was no need to hide her feminine self from these learned men and women anyway because of their close access to her and her palace. But for the common man or woman who could not read and who might not understand such academic explanations, Hatshepsut presented a simplified and unassailable image of idealized and youthful masculine kingship. For them, she became what everyone expected to see – a strong man able to protect Egypt’s borders and a virile king able to build temples and perform the cult rituals for the gods.” Cooney, The Woman Who Would be King, 232.

Bibliography

- Allen, James P.: „The role of Amun“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, 83-87, New York. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Bickerstaffe, Dylan: „The Burial of Hatshepsut“ in Heritage of Egypt 1, 3-14 (2008), Cairo: Al-Hadara Publishing.

- Bryan, Betsy M.: „The temple of Mut: New Evidence on Hatshepsut’s Building Activity“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, 181-184, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Bunson, M. R The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, New York: Gramercy Books, 1999.

- Cooney, Kara: When Women Ruled the World, Six Queens of Egypt, National Geographic, 2018.

- Cooney, Kara; The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt, New York: Crown, 2014.

- Diamond, Kelly-Anne: „Hatshepsut: Transcending Gender in Ancient Egypt“, in Gender & History, Vol. 32 No. 1, (2020): 168 – 188.

- Dorman, Peter F.: „Hatshepsut Princess to Queen to Co-Ruler“, Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, 87-91, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Grimal, Nicolas: Historia del antiguo Egipto, Madrid: Acal S. A., 1996.

- Gylors, Kristen „A Royal Queer: Hatshepsut and Gender Construction in Ancient Egypt“ in Shift, 8, (2015): 49-60.

- Hilliard, Kristina; Wurtzel, Kate: „Power and Gender in Ancient Egypt: The Case of Hatshepsut“ in Art Education 62, no. 3, (2009): 25-31.

- Keller, Cathleen A.: The statuary of Hatshepsut in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, 158-173, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Khalil, Radwa; Moustafa, Ahmed A: Moftah, Marie Z.; Karim, Ahmed A.: How Knowledge of Ancient Egyptian Women Can Influence Today’s Gender Role: Does History Matter in Gender Psychology? in Frontiers in Psychology, 7 (2016).

- Kuper, Kathleen ed.: The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people, The 100 most influential women of all time, New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, 2010.

- Laboury, Dimitri: „How and Why Did Hatshepsut Invent the Image of Her Royal Power?“ in Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut, ed. Jose M. Galan, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman, 49-93, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, SAOC 69, 2014.

- Laporta, Virginia: „La figura regina de Hatshepsut: una propuesta de análisis a partir de tres cambios ontológicos“ in Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 10, (2012): 83-115.

- Macy Roth, Ann: Models of authority Hatshepsut’s Predecessors in Power in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, 9-15, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Margetts, E. L: „THE MASCULINE CHARACTER OF HATSHEPSUT, QUEEN OF EGYPT“, in Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 25, No. 6, (1951): 559-562.

- Matić, Uroš: „(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal“ in Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 23(3),(2016).

- Novak, Grga: Egipat: prethistorija, faraoni, osvajači, kultura, Zagreb, 1967.

- Pierrotti, Nelson: „El rol de la mujer en el Egipto faraónico. ¿Qué oportunidades tuvo en la vida social, política y religiosa?“ in Clio. Revista de Historia year 15 (2016).

- Robins, Gay: Las mujeres en el Antiguo Egipto, Madrid: Akal Ediciones, 1996.

- Roehrig, Catharine H.: „Introduction“ in Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, ed. Catharine H. Roehrig with Renee Dreyfus and Cathleen A. Keller, 2-6, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Ryholt, Kim S. B.: The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 BCE Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997.

- Sabbahy, Lisa: „Queens, Pharaonic Egypt“ in The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, First Edition, ed. Roger S. Bagnall, Kai Brodersen, Craige B. Champion, Andrew Erskine, Sabine R. Huebner 5705-5709, West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing, 2013.

- Seawright, Caroline; „The Process of Identification: Can Mummy KV60-A be Positively Identified as Hatshepsut?“, ARC2EGY, 1-17, 2012.

- Szafrański, Zbigniew E.: „The Exceptional Creativity of Hatshepsut“, in Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut, ed. Jose M. Galan, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman, 125-139, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, SAOC 69, 2014.

- Tomorad, Mladen: Staroegipatska civilizacija sv. 1: Povijest i kultura starog Egipta, Zagreb: Sveučilište u Zagrebu – Hrvatski studij, 2016.

- Tyldesley, Joyce: Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt, London, 1994.

- Valero, Luis Tomas Melgar: Mitovi sveta, Beograd: Laguna, 2017.

- Watterson, Barbara: Women in Ancient Egypt, Gloucestershire: Amberly Publishing, 2013.

Originally published by Analize: Journal of Gender and Feminist Studies 17:31 (2022, 149-159) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.