Persepolis was conceived by the Achaemenid monarchs as a showcase for the world.

By Christian San José Campos

PhD Candidate in Ancient History

Alcala de Henares University

Abstract

The present work is intended to analyse the actions carried out by Alexander the Great at Persepolis to, lastly, achieve an interpretation of the events and the fire. These objectives will be attained through the division and analysis of all the details available for Alexander’s study in Persepolis: the background, the archaeological data, the literary sources and the interpretative currents that have had the greatest impact among historians.

Alexander the Great at Persepolis is one of the most puzzling questions for Macedonian scholars, having as many interpretations as researchers have approached it. Likewise, the precious works of Castaigne, the portentous paintings of Leclerc and the wonderful paintings of Le Brun are replaced with the torment depicted by Rochegrosse in his 1890 L’Incendie de Persepolis. However, what do we know about Alexander’s stay in Persepolis? What was the reason for burning the city? When did it take place? The aim of this paper is to analyse all the events surrounding Alexander’s stay in Persepolis in order to answer these questions.

Introduction

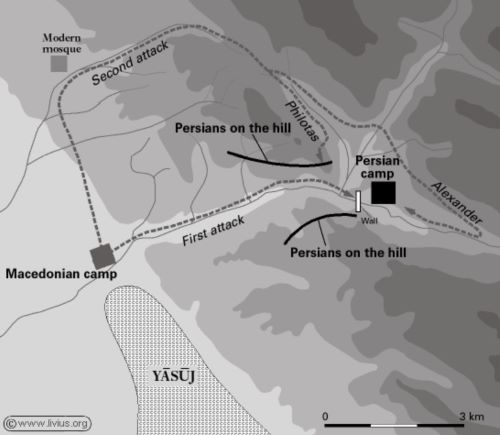

After the capture of Susa, Alexander seized the spoils and placed the royal prisoners in what some researchers have described as “golden cages”1, where they were nothing more than prisoners securing the viability of their claims to the vacant throne of Darius III, removing any viable opposition2. In any case, the Macedonian monarch did not intend to settle in Susa, his target being Persepolis. In this respect, Alexander was conscious that control of the heart of the empire was decisive for the conclusion of the war and that, if the rumours about the riches of Persepolis were true, he had to secure the treasure before the satrap Ariobarzanes could transport it elsewhere. At the end of 331 BC, when the Iranian winter was at its harshest, Alexander decided to travel the route between Susa and Persepolis3, choosing an itinerary that turned into a military campaign in which the protagonists were Ariobarzanes4, the resistance organised around the so-called “Gates of Persia”5, Alexander’s wit and the river Ares(Pulvar)6. Alexander finally reached Persepolis in December-January 330 BC.

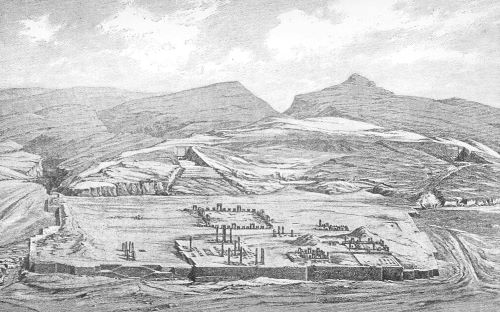

The famous Persian capital, whose name was Parsa7, was called Persepolis, “the city of the Persians”,by the Greeks8, unknown to the Hellenes until Alexander’s conquest9 and subsequent mention of Diodorus10, following Clitarchus’ source. The construction of the city was started in 515 BC by the monarch Darius I11, carefully choosing the location of the site in a large area at the foot of the sacred mountain dedicated to Mithra;therefore, we must add the undeniable sacred connotations of the location to its good geographical position12. Following these parameters, Darius I decided to give substance to constructions that had begun previously13, setting up, as the first major architectural work of new urban planning, the construction of a monumental platform of some one hundred and twenty-five thousand square metres14, a platform on which the ceremonial palaces, fortifications, living spaces and treasury were built.

The urban layout of Persepolis was predominant until the 2000s15 but has been overtaken in recent years by French, Italian and Iranian excavations16, proposing a new historical and interpretative context. The new archaeological corpus suggests that Persepolis was highly stratified, articulating a widely distributed city with no fixed administrative patterns between living zones, the area of aristocratic character and the spaces destined for economic activities17. This series of findings has enabled some authors, such as Boucharlat, De Schacht and Gondet, to propose that Persepolis was a region of occupation and exploitation rather than a population clustering unit18, peculiarities that distinguish it from other major capitals such as Susa or Babylon. In any case, within the palatial urban complex of Persepolis, the great hall of the monarch or audience hall stood out above the rest, and still does to this day. Its monumentality and magnificence constitute one of the most obvious examples of the construction and architectural capabilities of the ancient world19, as Plutarch records20. In this respect, the audience hall at Persepolis represented one of the paradigmatic architectural examples of Achaemenid politico-religious propagandistic iconography21, this room being accessed via two staircases22 on whose walls, through the numerous friezes and reliefs that decorated and accompanied the path of ascent to the monarch23, the entire protocol of the Achaemenid court was reflected24.

In sum, we can establish that Persepolis was conceived by the Achaemenid monarchs as a showcase for the world25. Thus, from Parsa, the monarchs expressed all the propagandistic connotations of Persian domination over the other peoples of the empire26, consolidating it as one of the great ideological-propagandistic centres of their power27. These attributes were reinforced by Persepolis’ unique geographical position as the “epicentre of the empire”, which made it the place where foreign embassies were to seek audience with the king28. In short, Persepolis can be considered one of the great capitals of the Achaemenid Empire29.

Precedents

The various studies devoted to the burning of Persepolis often overlook Alexander’s initial moments in the city, and we would therefore like to make some observations about this phase of Alexander’s and his army’s stay in Persepolis. If we follow the narrative development of the classical sources30, we can see a first stage of the Macedonian army’s stay in Persepolis where the sacking of the city took place between the end of December 331 BC and the beginning of January 330 BC.

From the surrender of Sardis by Mithrenes in the summer of 334 BC31 Alexander opted for a policy of rapprochement with the Iranian nobility32, a policy of tact towards the defeated33. These diplomatic strategies brought the Macedonian various rewards, with the corresponding prior military victory, such as the opening of Babylon by Mazeo34. In this respect, Alexander’s entry into Persepolis must be framed within these policies of mutual understanding, for the governor of Persepolis, Tiridates (kyrieuontos), opened the gates of the city in exchange for a large payment from the royal treasury35. The problem arose when Persepolis, following the pattern of the other Achaemenid cities which surrendered and were not conquered, was treated differently. What is the reason for this distinction by Alexander? In our view, this question should be approached from three different perspectives: a re-reading of the initial sacking, the events leading up to it, and the question of Alexander and Panhellenism.

First, the initial sacking of the city. The narratives of Arrian and Plutarch offer sparse information and details36, the narratives of Diodorus and Curtiusbeing the most explicit about the event37. Through these two accounts it can be seen that the real highlight of the looting was the almost obsessive search for the immense loot: “οἱδὲΜακεδόνες ἐνημερεύσαντες ταῖς ἁρπαγαῖς τὴν ἄπληστον τοῦπλείονος ἐπιθυμίαν οὐκ ἐδύναντο πληρῶσαι”38. Consequently, we would like to make a few observations. Several authors have developed hypotheses about the initial looting of Persepolis which, in our opinion, are excessive. The case of M. Brosius is the most notable, arguing that: “This act of hooliganism on the part of the Macedonian soldiers was a senseless act of unprovoked violence, brutal killing and deliberate destruction of the central capital of the Achaemenid kings”39, finding precedents in Ciancaglini: “il trattamento riservato ai vinti fu meno efferato”40 and Lane Fox “ground zero”41. In this respect, we believe that Brosius is correct in establishing that there was no precedent for such behaviour in Alexander’s campaign, and we also give credence to the assertion that there was no resistance during the course of the sacking42.

However, we believe that Brosius, Ciancaglini and Lane Fox all go too far in their assertions. First of all, Diodorus’ account, like Curtius, shows a motivation whose main driving force is the lust for riches. In other words, the basic element of the story is the greed for booty, which in no case should be extrapolated, for lack of evidence, to a plunder full of murder and violence. Similarly, the excessive literary taste provided by Diodorus and Curtius in their respective narratives should be understood as a gesture intended to excite the feelings of the Greco-Roman reader to whom it was addressed43, an approach that would have a double reading. On the one hand, it allows us to understand the excessive recreation of the greed for wealth and, on the other hand, it enables us to suggest that the lack of mentions of brutal murders or extreme violence would imply their non-existence. Likewise, the omission of this initial act by the army in the accounts of Plutarch and Arrian is symptomatic in that looting was not exceptional. That is, in the terms of “hooliganism” there is no literary evidence to indicate the exceptional brutality of the pillage of the urban area and private residences44. As a final argument against these hypotheses, we would like to point out that there are no allusions to the destruction of houses or food reserves, and that the army did not penetrate the palace areas until Alexander’s arrival45. In sum, the evidence seems to indicate that the looting of private houses and the burning of some private properties must not have been out of the “routine” of this kind of praxis46. Likewise, the initial looting was a programmed and planned act in view of the immediate establishment of the army in the following months47.

Having established the character of the initial looting of Persepolis by Alexander’s army, we must turn to the events leading up to it: the harsh and unexpected military campaign en route to the city. The stiff resistance organised by Ariobarzanes48 forced Alexander to use all his military ingenuity. It is not our intention to develop the military process undertaken by Alexander49, but we will indicate that it was one of the most notorious episodes of the Macedonian’s clear military brilliance50. In any case, it seems likely that the harshness of the confrontation provoked a certain tension in Alexander and increased the army’s pretensions to behave like an army after three years of campaigning51. Following these assumptions, Morrison considers that the initial looting of the city was deeply linked to the morale and stability of the troops52, and Heckel also points in this direction, adding that even if the entire army was not present53, the loot would be divided into quotas corresponding to merit and status54. Consequently, the sacking of Persepolis could be seen as a clear message to the pockets of resistance that still existed in the empire and a just reward for the army that, up to that point, had not sacked any cities on Alexander’s orders.

Finally, we would like to address the question of Alexander and Panhellenism. If we follow the propagandistic terms expressed by classical authors, see, for example, the descriptions of Persepolis by Curtius and Plutarch55, we could consider that the sacking of the city was more than justified. Acertain pattern of propagandistic ideals associated with Alexander’s campaignscan be tracedwithin the narrative structure of the classical sources, the “Panhellenic campaign”being one of the most intrinsically linked propaganda devices56, where the two main objectives were “the war of retaliation”and “the war of liberation”57. Consequently, the treatment of Persepolis would be justified because of its configuration within the itinerary of Alexander’s campaign as the original geopolitical core of Hellenic ills58.

However, it must be established that these artificial constructions are nothing more than narrative creations devised by the entourage of intellectuals in Alexander’s service and disseminated by propaganda, in what some authors have defined as the “house of propaganda”59 or “official photographers”60. In other words, Alexander deliberately employed propaganda to construct and transmit a series of specific connotations to serve his interests61. The question that arises from these approaches is: are they mere propagandistic constructs or did they have any credence in Alexander’s mentality? In this respect, most historiography has considered Alexander’s sincere assumption of the Greek mentality to be debatable to say the least62. Some elements that have contributed to the creation of this idea are the very limited role the Greeks played during the campaigns against the Persians63 or the articulation of Alexander’s campaign by Philip II and his planning of territorial conquest for the kingdom of Macedonia64. However, there are some dissonant voices on this matter:Hatzopoulos65 and Flower66 consider the absolute negation of Panhellenism to be utopian, opting for a more flexible view where the Panhellenic campaign and the political interests of the monarch were not necessarily mutually exclusive67. Thus, we can find practical examples that support these propagandistic ideas directed at the Greek world, such as the series of rituals performed by Alexander to reconnect with the Trojan War, the revenge against Xerxes I and the invasion of Greece68. Despite these considerations, when the researcher approaches these questions, he is confronted with questions such as: to what extent did the Greek cities of Asia Minor want to be liberated from a stable and beneficial imperial system?69 This demonstrates the extreme complexity of the Panhellenic issue and the impossibility of dealing with it here70.

Having laid the foundations of the conflictual nature of this subject, we shall now proceed to try to shed light on the issue of the mutilated Greeks who came out to meet Alexander on his arrival at Persepolis. In their accounts, Diodorus and Curtius explain how numerous mutilated Greeks came out to meet Alexander71. In this sense, as Domínguez Monedero points out, most of the current historiography is against this event being excessively convenient for Alexander’s later actions in the city72. However, for Briant or Domínguez Monedero himself, it is not unreasonable to think that a certain number of Greeks inhabited Persepolis and found themselves in the situation described in the sources73. In this respect, we consider that the dramatism (πάθος) of the scene invites us to suspect once again the Panhellenic issue through propaganda. In our opinion, Diodorus and Curtius faithfully convey Clitarchus’74 account, fallaciously symbolising the unfortunate ones who were nothing more than the representation of Greek victimhood that the Panhellenic campaign intended to avenge.

In conclusion, the analysis of the sacking, the possible consequences of the resistance offered before reaching the city, the morale of the army, the configuration of Persepolis itself within Alexander’s propaganda itinerary, together with the pan-hellenic aspects (beyond the strategies of Alexander and his retinue of intellectuals),invite us to consider that there was a series of conditioning factors that triggered the special animosity towards the city and the initial sacking.

Archaeology and Its Responses

Having set out the possible factors that led to the initial treatment of the city, we will now try to trace the reasons for and chronology of the fire at Persepolis. Any enthusiast who goes to the classical sources and reads about the Persepolis incident might come to the conclusion that the looting and the fire took place in an extremely limited time frame, and therefore the first conclusions would be that the fire took place in the month of January itself. In an attempt to throw light on the confusing question of the fire at Persepolis we will focus on the archaeological analysis of the city, which in turn will be aided by the logistical question and by archaeological data concerning other cities of the empire.

Scientific investigations of the ruins of Persepolis began in 1924 under the auspices of the Iranian government, a project that was delegated to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago under Professor Herzfeld from 1931 to 1934. Subsequently, from 1935 to 1939, the scientific project was entrusted to Schmidt, giving rise to an enormous scientific development which resulted in the magnificent contributions of 1953, 1957 and 197175. In the 1960s, Wheeler provided the phrase that perhaps best defines the importance of the Persepolis fire and its archaeological project: “The burning of Persepolis marked a major divide, not merely in the particular history and archaeology of Eurasia, but in the broad history and archaeology of ideas”76. Archaeological surveys at Persepolis continued to develop, achieving great success in the 1980s with the largest and most varied collection of Achaemenid materials to date77, exceptional in its richness and volume: administrative clay tablets, rings, prints, ritualistic objects, glass, stone and metal trinkets, coins, sculptures, personal ornaments, military equipment, foreign items of great symbolic value, votive objects, etc.78.

Following these assumptions, archaeological research in the 1990s found the first major interpretative pillar in Hammond’s studies79. Hammond estimated that the excavations uncovered an extensive amount of material of enormous value that did not fall prey to Alexander’s army: “The pillaging itself was done not only at speed, as the excavators noted, but also during a short time, so that the pillagers were able to collect and remove only —what was most valuable and easily carried off”80. Consequently, Hammond considered that the chronology offered by Plutarch81 was incorrect82, as the destruction of the palace would have taken place “immediately after the pillaging”83. However, despite the haste of the events, Hammond interpreted it as calculated arson, identifying several foci and a certain coordination, a hypothesis that would coincide with the excessive speed with which the sources narrate the events at Persepolis84.

After Hammond, the archaeological question continued to be debated until the approaches put forward by the Ottawa professors Bloedow and Loube85, who proposed interpretations that refuted Hammond’s ideas. The Ottawa professors considered that the materials found in the excavations were, for the most part, modest objects in both quantity and quality compared to the initial treasure86. In this respect, the case of the twenty-one coins is significant as they were coins87 which, even in Alexander’s time, would have been considered outdated, and none of them were Achaemenid88. Similarly, they argued that Hammond’s theory did not explain the chronology because: “It is therefore important to realize that in this respect the archaeological evidence is completely neutral”89. However, Bloedow and Loube agreed with Hammond on establishing that the archaeological evidence supported a well-organised arson attack, a hypothesis that has been maintained in subsequent archaeological analyses, despite interpretative fluctuations90. On the other hand, Sancisi Weerdenburg’s interpretative contribution starting from the archaeological data was extremely significant. Sancisi Weerdenburg’s analysis indicated that the buildings where the fires originated were the residential palace of Xerxes (Hadish), the apadana, the throne room and the treasure room, a series of buildings associated with the monarch who destroyed Athens91. In other words, archaeology offered a first convincing argument for the destruction of the city, establishing that the Panhellenic issue played a primary role in the burning of Persepolis.

However, despite the essential data provided by these analyses, archaeological studies leave some questions unanswered, such as: was the loot from Persepolis really exceptional? Can archaeology provide chronological answers? In order to answer these questions, the archaeological data must be complemented with the logistical question and records from other excavations. Firstly, the spoils of Persepolis. On the one hand, Arrian gives us a brief account of the event92, and in general of what happened in Persepolis, and does not give any data on which to base our estimates. On the other hand, we find the data established by Plutarch and Strabo93, who give a figure of forty-fifty thousand talents and, finally, we find Curtius and Diodorus94, who propose the figure of one hundred and twenty thousand talents. In order to establish which version is more accurate, we will look at the Pasargadae archaeological project95. The documentation collected in the Pasargadae treasure area does not come close in quantity or quality to the Persepolis records. According to authors such as Stronach96, this lightness of precious and valuable objects is due to the special effort made by Alexander to clean the treasure rooms, which would have contained some six thousand talents97. In our opinion, the records from Pasargadae allow us to validate the exceptional nature of Persepolis because, after several months of occupation, looting and logistical organisation, the persistence of objects would indicate that they were probably left there due to lack of interest98. Likewise, we would like to clarify that, when we establish the viability of the estimates given by Curtius and Diodorus, we do so from an approximate assumption. This is because the data offered by the sources do not include the measurement of the value of furniture, vessels, small pieces of gold, decorative pearls, etc. Consequently, what we extract as true is that, from among the treasures found by Alexander in Asia, this would be the one with the highest value99.

Once we have established the veracity of the sources in terms of the approximate reality of the Persepolis treasure, we can deal with the chronological question starting with the logistical issue. According to Diodorus, Curtius and Plutarch100, in order to transport the wealth stored in Persepolis, Alexander had to mobilise thousands of pack animals from Susa, Babylon and Mesopotamia. In other words, we would be facing a logistical problem of the first magnitude101. The logistical question was first interpreted by Engels, who did not believe the estimates of Curtius and Diodorus because of the various logistical problems presented, such as the carrying capacity of the animals, their number and the journeys they would have to make102. However, Holt has recently corroborated the feasibility of the operation in the time stipulated by Plutarch in spite of the difficulties encountered103. Therefore, there would be a dual process: firstly, sending the orders to the respective cities, preparing the animals, transporting them along the imperial routes during a period of snowfall and loading them at Persepolis, and secondly, and in parallel, organising, cataloguing and distributing the treasure.

In conclusion, the archaeological data are very useful. First of all, the most important piece of evidence from the excavations is that the fire at Persepolis was a premeditated and well-organised event. Secondly, the excavations at Pasargadae and Persepolis allow us to support the estimates of Curtius and Diodorus, confirming that the treasure of the city exceeded that of the other cities of the empire, and Cahill would not be wrong in proposing that Alexander had to move about three tons of treasure104. On the other hand, the study of the origin of the outbreaks of fire presents a panorama in which the Panhellenic question is of transcendental importance in explaining the fate of the city. Finally, the creation of a complex logistical system would be a further argument, in addition to the archaeological question of a premeditated fire, Plutarch’s chronological data, the logical assumption that Alexander would not set fire to his own residence while he still lived there, the first visit to Pasargadae and the incursions into the mountainous areas, that the fire necessarily took place at the end of the army’s presence in the city.

The Literary Testimonies

The accuracy provided by archaeology is unsatisfactory because of its limitations when it comes to outlining an explicative reconstruction of the event, which is why researchers have been pushed to trace literary sources, which are certainly where the great academic battlefield of the fire at Persepolis lies. Through the sources we can find two different accounts: the one offered by the Vulgate and the one given by Arrian.

The well-known episode about the feast of Persepolis, the wine and Thaïsis taken up by the tradition of the Vulgate. Diodorus, Curtius and Plutarch agree on developing a story where feasting and alcohol are the main characters until the introduction of Thaïs as a fundamental tool, either as a driving force or as a stimulus, for the ignition of the palaces105. This event has been taken up almost without filter by the historiographical currents that have considered Alexander as a monster debased by alcohol, cruel and evil. For some of these authors, such as Gehrke, Hamilton or even Lane Fox, there is no doubt that the ultimate causes of the fire at Persepolis were wine and Thaïs106. To us these assumptions do not seem to be very explanatory and are even lazy. In this respect, the literary question could be widely debated. For Heckel, the Thaïs affair would be linked to the narrative of the Greeks at the gates of Persepolis and would put the finishing touch to the propaganda of the Panhellenic enterprise107. Bosworth and Briant also question the account and the narrative basis of Clitarchus of Alexandria108. In our opinion, leaving aside literary reflections, the various archaeological studies (presented in the previous chapter) have unanimously shown that the burning of the city was planned and coordinated and, consequently, the speculative theories about a spontaneous fire caused by alcohol are disarticulated.

On the other hand, we find the narrative of Arrian109. What Arrian brings together in his version is undoubtedly part of the problem that Alexander and his high state must have faced when the idea of the destruction of the palaces was considered. In this respect, Briant is right in suggesting that Parmenion was to be consolidated as the personification of a group opposed to Alexander’s decision to set fire to the palace110. Likewise, the omission of the feast and Thaïs from the story could be interpreted in various ways. As far as the feast is concerned, we believe that during the prolonged period that the Macedonian forces occupied Persepolis, it is more than possible that there was some kind of celebration of the successful campaign, the capture of the city or the riches gained, a feast that would be used by Clitarchus as a background of his manipulation. Therefore, the fact that Arrian does not mention this festivity implies that it did not have any transcendence or exceptionality. Moreover, Arrian would not omit the existence of an important celebration, even more so when it would have tragic connotations111 that he would later criticise personally112. As for Thaïs, some authors such as Tarn113 have argued in favour of the non-existence of this character, while other scholars such as Borza or Nawotka114 consider that Ptolemy would have eliminated Thaïs, his wife, from his account in order to cover her up, being reflected in Arrian’s narrative. In our opinion, there is no evidence against the participation of Thaïs in Alexander’s campaigns as Ptolemy’s concubine. However, the assumption of this character as the active or passive driving force of the fire would have to be related to her double status as an Athenian and as a “concubine”, elements that would lend themselves to literary artifice.

In conclusion, and agreeing with Morrison115, we consider that Clitarchus could have articulated a narrative in which dramatic and theatrical issues took possession of the story from abasis of reality, creating a false narrative in which the aim is to develop, in an excessively forceful manner, the propagandistic connotations that articulated the Panhellenic campaign. We can also draw several conclusions from Arrian’s account. Firstly, the account suggests a long debate about the fate of the city, an approach that would have been supported by the planning shown by archaeology. Secondly, Arrian’s narrative makes it possible, although by different paths, to stipulate that both traditions develop within a common framework: the Panhellenic question, parameters that would confirm the data provided by archaeology. However, before proceeding with a final reading of the fire at Persepolis, we would like to analyse the two interpretative schools of thought that have had the widest historiographical following when it comes to establishing an explanation for the fire at Persepolis.

A Sea of Interpretations

Overview

The interpretations of the Persepolis fire are almost equal to the number of authors who have dealt with it, which is why in the following lines our intention is to analyse the two academic traditions that have had the greatest following and continuity among researchers: the Greek perspective of Agis III and the Iranian approaches.

The Greek Perspective: The Case of Agis III

Among the numerous explanatory proposals for the fire at Persepolis, one of the most widespread and debated is the hypothesis of Agis III116, which has mainly been discussed by Badian117 and Borza118, and we therefore intend to follow their interpretative approaches. First, Badian stipulated that Alexander’s articulation of the Panhellenic trump card during the campaign was merely perfunctory insofar as the Macedonian “plays his game well, as long as he needed Athens”119, a claim followed by Briant120 and whose trail can be traced after the return of a number of statues usurped by Xerxes from Athens itself121. In this respect, Badian considered that the burning of Persepolis was carried out in order to fight the rebellion of Agis III “old slogans, long abandoned, were suddenly relevant”122, outlining that the only explanatory possibility was the war in Greece123. Badian’s approach was followed years later by a number of scholars, such as Hammond, who argued that: “to the Athenians the burning of the Palace at Persepolis was a striking demonstration that the Greeks of the Common Peace in collaboration with Macedonia had triumphed in their war against Persia”124.

In our view, Hammond and especially Badian are wrong in their assertions. Following these assumptions, the essential argument put forward by Badian is the question of time, which we would like to analyse. The scholar’s estimates of the time frame suggested that Alexander received the information after the fire125. However, although some authors proposed even later dates for the death of Agis III126, most modern historiography follows Borza’s estimates, deciding to provide a date closer in time, establishing the death of Agis III in the autumn of 331 BC127. In this regard, it should be clarified that the increased chronological lapse is not equivalent to guaranteeing that Alexander received the information about the death of Agis III before his departure from Persepolis. Also, as conjectural as it may seem, Alexander’s time estimates and handling of the information are merely academic estimates due to the total lack of records. We would, however, like to make a few observations.

Following Badian’s assessment, a journey from Sardis to Susa would take three months128, and Borza stipulates another month to travel from Europe to Susa129. Along this line, we could establish that the importance of the death of Agis III and the end of the rebellion must have been a major news item that, without any delay, was set in motion. It would also not be unreasonable to think of the formation of a small, swift retinue which, despite the geographical and seasonal difficulties, would be agile in its journey, travelling along frequently travelled routes due to Alexander’s constant communications with Greece130. Given these premises, it seems extremely difficult to assimilate the fact that between approximately the end of September, beginning of October (death of Agis III) and mid-late May (fire of Persepolis) there was no communication between Alexander and Greece. Moreover, even assuming Badian’s questionable assumptions about a fire aimed at the Greek world on the occasion of the revolt of Agis III, we consider that a strategist and tactician like Alexander would not take any decision of such magnitude without first having received a reliable report on the situation131. We do not therefore subscribe to the hypothesis that proposes Alexander as a commander who was driven by a supposed insecurity motivated by ignorance. In this respect, studies have been developed on the primary role of Alexander’s intelligence and communication services during his campaigns, despite the scarce literary references to them132.

In conclusion, we consider Badian and Hammond’s time estimates to be mistaken. Following the hypotheses outlined by Borza or Engels, Alexander received the information about the defeat of Agis III while still at Persepolis. Likewise, it would be unwise to think that, with an intelligence and communication system such as that developed by Alexander during his campaigns, there would be room for a period of six/seven months without any information, more so in the case of a news item of the first magnitude such as the defeat of Agis III.

Iranian Approaches

For some authors, Panhellenic approaches have proved to be of little explanatory value in resolving the Persepolis fire, and consequently most scholars who have approached the subject from the early 1980s until the end of the last decade have approached the problem of the fire from another perspective: the Iranian one.

Along this line of argument, one of the most notable cases is that of Green. The British professor’s hypothesis is that Alexander’s motivation for staying in the city was the Persian New Year Festival. This interpretation would have a strong religious, propagandistic and ultimately political component, as Alexander sought to set himself up “as Ahura Mazda’s vice-regent on earth”133. This interpretative theory would find its precedent in Balcer134, who proposed a hypothesis centred on the political and religious question following the Persian festival and the legitimation granted by Ahura Mazda135. On the other hand, Green stated that: “The palace and temples, the great apadana or audience hall, the whole complex of buildings which formed the city’s spiritual centre, on that vast, stage-like terrace backed by the Kuh-i-Rahmet Mountains-none of these had been touched. In other words, the New Year Festival could still be held”136. Furthermore, the initial sacking of the city was presented by the author as an act of self-restraint by the army and restraint on Alexander’s part, demonstrating that the Macedonians were not barbarians and respected sacred places. Also, according to the London professor, Alexander sensed that the celebration would not take place, triggering the burning of the palaces, thus sending a strong message to the Persian Empire that the glory days of the empire had come to an end. In the end, Alexander did not establish himself as the successor of the Achaemenids, nor as Ahura Mazda’s chosen one, but as their new lord by law of conquest.

In our view, these hypotheses raise a number of difficulties. Firstly, the arguments put forward by Green and Balcer to lend credibility to the temporal question are excessively light.To consider that Alexander’s prolonged stay in the city was motivated by the expectation of an uncertain festival seems to us questionable to say the least. Equally, the discussion of the initial sacking of the city in the previous chapters indicates that the army had explicit orders from Alexander to leave the palace area intact until his arrival, and therefore Green’s speculation of an initial sacking as a sign of the Macedonian army’s restraint and respect for the Persian sacral areas is invalid. Similarly, both authors assume a change in Alexander’s mentality as a result of the non-celebration of the event, while Green went further in assuming that: “If negotiations were ever opened on this tricky subject, they soon broke down”137. In other words, Green’s hypothetical proposal is based on an event that Alexander supposedly expected, which is not supported by the sources, and is based on conjectured negotiations that are also not supported by the sources. We should also be aware of how unconvincing it would be to assume such “childish” behaviour on Alexander’s part, burning the city simply because he did not know what to do with it: “his mind finally made up. The city must be destroyed”138, following the alleged rejection of hypothetical negotiations.

Alongside the exclusively Iranian viewpoint of Green and Balcer, we find the theories of Briant and Nawotka. The French scholar presents the fire of Persepolis as an event aimed at the Persian world139, where the decisive event would be the visit to the tomb of Cyrus I in Pasargadae140: “If the decision to burn the palaces was taken soon after Alexander’s return from Pasargadae, it simply shows that his piety toward Cyrus’s tomb had not diminished Persian hostility”. In addition “The burning of the palaces was a signal to the Persians that their days of imperial glory were over, unless they came over to the side of the conqueror”141. These theories would find their continuity in Nawotka: “The burning of the palaces in Persepolis should be perceived as the high point in Alexander’s campaign of terror, waged in Fars when conciliatory gestures had failed”142. In a way, Briant and Nawotka establish that Alexander’s visit to Pasargadae and the persistence of Iranian resistance played the same role as the Persian New Year holiday in Green and Balcer’s hypothesis, implying a change in Alexander’s mentality and leading to the planning of the fire143. Consequently, we would like to make some considerations.

f we follow Nawotka and Briant’s interpretation, the visit to Pasargadae would have taken place after the incursions into the Persia’s hinterland (Curt. 5.12-18), which lasted about a month144. This view seems to be corroborated by the sources since, although Curtius mentions the treasure of Pasargadae before the raids145, he does so for numerical reasons, giving greater credibility to the fact that after the raids it went to Pasargadae, as he seems to indicate later on: “Dona deinde amicis ceterisque pro cuiusque merito dedit. Propemodum omnia, quae in ea urbe ceperat, distributa”146. Similarly, archaeological, logistical and logical data establish that the burning of the palaces took place before the departure of the army, and therefore Alexander must have spent the whole winter in Persepolis in order to make the raids and the journey to Pasargadae about a month before his departure. Following these approaches, the literary narrative could lend credibility to the hypotheses proposed by Briant and Nawotka, as well as the archaeological data (which they do not contradict) and the logistical question, since the six thousand talents obtained at Pasargadae did not have to be added to the logistical apparatus when they were distributed.

However, the fact that the data provided are consistent does not imply that they are accurate. Without wishing to reiterate the ideas put forward to refute Green and Balcer’s ideas, we will say that there is no evidence to show a change in the monarch’s mentality; the initial plunder would present Alexander’s lines of action towards the city. Likewise, the ideas developed by Briant and Nawotka present a number of questions and assumptions that neither of them have answered in their work. First, they assume that Alexander did not decide to set fire to the city practically until his departure, implying a last-minute change and eliminating the debate established in Arrian’s account. Following these assumptions, we ask: did the idea of the fire not appear in Alexander’s head until he went to the tomb of Cyrus I? In other words, the authors assume hypothetical hopes of Alexander not supported by any record, interpretative difficulties amplified by the analysis of Alexander’s second stay at Pasargadae147. In this respect, we have no data on Alexander’s first visit to the ancient Achaemenid capital, which took place during his stay at Persepolis. Only the usurpation of the treasure148 has been confirmed by archaeology149, but the second visit to Pasargadae has been well recorded by Arrian150. In this second stay, after the campaign in India, Arrian conveys how Alexander expresses the great esteem he felt for the monarch. The event has a markedly personal tone of flattery and respect devoid of the deep political and religious overtones that Nawotka and Briant assume. In our opinion, and lacking the first story, it seems to us excessively adventurous to endow the event with such relevance, even more so when Arrian, in the account of the second visit, does not include itin his narration.

Moreover, even if we were to assume the political and religious connotations that these authors propose, was Alexander not conscious of the significant pockets of resistance in the Empire? The Iranian approaches would lead us to assume total ignorance on the part of Alexander of his immediate context. Therefore, we consider that these parameters would imply a certain foolishness in Alexander of which we disapprove. The monarch would have been aware of the situation both through the incursions into the desolate mountains of Persia151 and through the aforementioned intelligence system152. Also, these interpretations raise a question mark over Alexander’s relationship with the Iranians: was Alexander unaware of the parameters of his relationship with the Iranian nobility? Bosworth, Brosius and Shahbazi’s studies on the subject put forward the two components that made the existence of such a relationship concrete153. The first component of the relationship was Alexander himself. The Macedonian understood the need to curry favour with the Iranian upper classes to favour his campaigns, needing the elites to be able to administer the territory, maintain a pacified rearguard, collect tribute and establish new levies in the empire154. In other words, without the collaboration of this Iranian aristocracy there was no chance of success155. Secondly, the Iranian aristocratic families themselves156 understood the need to deal and negotiate with the conqueror in order to preserve their dominant position in society157. Therefore, the administrative and economic situation did not really change much158. Following the approaches developed here, we dismiss the theory that Alexander was unaware of the limitations and parameters of the policy he himself had developed with the Iranian aristocracy.

In conclusion, these reflections would disarticulate the Iranian hypotheses, not to mention the problem of the survival of Darius III. Finally, we would like to add that these versions, approached from an exclusively Iranian point of view, would leave aside the common presuppositions in the literary versions. The fact that the rational version of Arrian and the irrational version of the vulgate coincide159 implies, in our opinion, that the official version intended to articulate the Panhellenic trump card. In short, the strictly Iranian visions pose a series of obvious problems, regardless of whether or not their data are consistent, and are therefore a series of interpretations created from the concatenation of assumptions or hypotheses that are truly difficult to assume due to the lack of solid arguments. In summary, we do not deny the final message that they incorporate into their readings: the glory days of the Persian Empire are over and Alexander has consolidated himself as conqueror and new lord of Asia160, but their argumentation is, in our opinion, excessively speculative.

Reconstructing Persepolis: An Interpretation

Having presented the issue, the archaeological and literary data, and the various interpretations, we will now proceed to develop an explanatory hypothesis for the fire at Persepolis. Firstly, the data provided by the analysis of the initial looting of the city. The Macedonians’ treatment of the city was a perfectly timed act, regardless of whether the trigger was the position Persepolis occupied in Persian mentality and religiosity, a hypothetical act of punishment for resistance, a supposed morale issue in the army, the problematic role Alexander gave the city in his Panhellenic and propagandistic itinerary or even the interconnection of all these factors. The reality of the event allows Persepolis to be placed in a distinguished position compared to the other imperial cities.

Secondly, the question of time. The characteristics presented in the initial sacking indicate that Alexander intended to settle in Persepolis for a period of time that it is impossible to specify, although in our view it would make sense to articulate that this period would last until the harshest part of the Iranian winter was over. During this period of rest for the army, Alexander also carried out several undertakings: the raids on Persia, the first visit to Pasargadae where he took possession of the entire treasure and, finally, the creation of the complex logistical system due to the immense treasure, although we do not know whether this was an aggravating factor in the extension of the time of occupation of the city. Finally, we must make the axiomatic logical argument that Alexander would not set fire to his own residence while he was still in it. In conclusion, in spite of the interpretative fluctuations, the sum of all these arguments invites us to give credibility to the period proposed by Plutarch161, establishing the fire in mid-late May, at which time the Macedonian army left the city.

Finally, the big question: why did the fire at Persepolis take place? Is it really a question that is impossible to answer?162 As we have developed, the hypotheses on the purely Iranian vision are, in our opinion, excessively speculative, requiring a notorious effort on the part of the researcher to accept a succession of certainly questionable hypotheses. On the other hand, the question of Agis III is disarticulated insofar as the time lapse established is hardly credible, and we do not share the vision of an insecure Alexander carrying out an action of such calibre merely because of a supposed lack of knowledge. However, the dismissal of Agis III’s argument as explaining the burning of Persepolis does not amount to a disarticulation of the Panhellenic component of the action. If we accept the background proposed by both the theatrical narrative of the Vulgate and the moderate account of Arrian we essentially obtain the same variable. It is most interesting how the two traditions are not mutually exclusive, but complementary in terms of the final message: the Panhellenic background is of crucial importance. At this point the question arises: did Alexander really assimilate the Panhellenic component or was it merely a propaganda tool? As we established in previous pages, it is not the purpose of this work to answer these questions, although it does concern us to establish whether or not Persepolis was an action executed following these parameters. In this respect, the answer is provided by archaeology. The archaeological data analysed in the present work indicate that the sources of the fire were the buildings associated with Xerxes. Although there are no records of the existence of “firebreaks” for the rest of the buildings, the fact is that there were no other sources of propagation, allowing the conservation of certain structures that still survive today. Thus, the archaeological and literary records point in the same direction. It could also be argued that Alexander had planned the burning of the city even before his arrival at Persepolis163, assumptions that would be supported by his initial marked treatment of the city and by the classical sources themselves: “σφόδρα γὰρ ἀλλοτρίως ἔχων πρὸς τοὺς ἐγχωρίους ἠπίστει τε αὐτοῖς καὶτὴν Περσέπολιν εἰς τέλος ἔσπευδε καταφθεῖραι”164. In conclusion, the initial sacking of the city, the various allusions in the sources to the position of Persepolis in Alexander’s itinerary, the politico-religious propaganda role played by Persepolis in the Achaemenid world, the concordance of the two literary currents in terms of background and the support of archaeology allow us to establish that the burning of Persepolis was a premeditated action justified by the articulation of the Panhellenic trump card.

On the other hand, we would like to point out that, although the explanation of the fire must be understood in a Greek key, the message was bidirectional, as a clear message was also articulated to the Eastern world: the Achaemenid Empire has been destroyed; the new conqueror and lord of Asia is Alexander. In this respect, perhaps the strongest evidence of this bilaterality is the articulation of various descriptions of Alexander: “monster”, “conqueror” and even “prophet” in later Persian literature165. In short, if all the solid evidence we have for the interpretation of the fire at Persepolis points to a Panhellenic question, why is it that Persepolis is one of the most debated questions in the historiography of Alexander the Great? In this respect, a brief final comment should be given due consideration.

Throughout the present work we have seen how the various events surrounding the burning of Persepolis, and this could be applied to all the actions of Alexander’s life, have numerous interpretations. This should not be surprising, since the great battlefield about Alexander is, precisely, the study of his sources. To what extent can historians study the figure of a character who was so successful in creating his own myth? How do we separate myth from reality, propaganda from veracity, the fictional from the real? The tortuous answer fosters the Macedonian’s vast bibliography and his virtually inexhaustible source of study. Similarly, historians often forget that Alexander was human, exceptional yes, but human, and as such his ideas, behaviour and goals were susceptible to change. Likewise, academic needs sometimes lead to the creation of unalterable approaches, motivations and aims that are often more in line with the author’s assumptions and the circumstances of their context than with the reality of the historical figure and his human condition166. It is precisely for this reason that the relationship between Alexander and the Iranians, as well as his motivations and aims at the time of the burning of Persepolis, contained a different set of characteristics to those established after the death of Darius III and the usurpation of Bessus. These two factors led to a change of context, generating the creation of new relations with the Iranians167. Clearly, the destruction of one of the most important religious and political centres of the Achaemenid Empire168 would precipitate his inevitable failure, and it is in this change of context, brought about by the new needs of his career as a conqueror and politician, that the causes of the regret noted in the sources must be traced169.

In conclusion, the evidence at hand indicates that the fire at Persepolis can be established as the paradigmatic example that Panhellenic assumptions were not limited to the propagandistic level. Similarly, these conclusions neither affirm nor deny Alexander’s sincere embrace of Panhellenic postulates due to the impracticality of delving into his psyche, but they do establish a reality: the Macedonian employed Panhellenism to satisfy his needs regardless of what they were, making Persepolis one of the fundamental examples for understanding Alexander’s success in creating his own legend.

Bibliography

- ALLEN, L. (2005): “Le roi imaginaire: an audience with the achaemenid king”, in R. FOWLER–O. HEKSTER (eds.): Imaginary Kings: Royal Images in the Ancient Near East, Greece and Rome, Stuttgart: 39-62.

- ANTELA-BERNÁRDEZ, B. (2019): Historia viva, Barcelona.

- BADIAN, E. (2012a [1966]): “Alexander the Great and the Greeks of Asia’, in E. BADIAN: Collected Papers on Alexander the Great, New York: 124-152 [Repr. from E. BADIAN (ed.): Studies in Honour of V. Ehrenberg, Blackwell: 37-69].

- —(2012b [1967]): “Agis III”, in E. BADIAN: Collected Papers on Alexander the Great, New York: 153-173 [Repr. from Hermes 95: 170-192].

- —(2012c [1994]):“Agis III: Revisions and Reflections”, in E. BADIAN: Collected Papers on Alexander the Great, New York: 338-364 [Repr. from I. WORTHINGTON (ed): Ventures into Greek History, Oxford: 258-292].

- BALCER, J. (1978): “Alexander ́s burning of Persepolis”, IA 13: 119-133.

- BARCELÓ, P. (2011): Alejandro Magno, Madrid.

- BIDMEAD, J. (2002): The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia, New Jersey.

- BLOEDOW, E.; LOUBE, H. (1997): “Alexander the Great under the fire at Persepolis”, Klio 79.2: 341-353.

- —(2003): “Why did Philip and Alexander launch a war against the Persian Empire?”, AC 72: 261-274.

- BORZA, E. (1971): “The end of Agis ’Revolt”, CPh 66.4: 230-235.

- —(1972): “Fire from heaven: Alexander at Persepolis”, CPh 67.4: 233-245.

- —(1977): “Alexander’s Communications”, Ancient Macedonia 2, 295-303.

- —(1996): “Greek and Macedonians in the age of Alexander: the Source Tradition”, in R. W. WALLACE–E. M. HARRIS (eds.): Transitions to the empire. Essays in Greco-roman history 360-146 BC, in honor of E. Badian, London: 122-139.

- BOSWORTH, B. (1980): “Alexander and the Iranians”, JHS 100: 1-21.

- —(1988): Conquest and empire. The reign of Alexander the Great, New York.

- BOUCHARTLAT, R. (2019): “Renewal and perspective in iranian archaeology over the last two decades”, ISIMU 22: 119-132.

- BOUCHARLAT, R.; GONDET, S.; DE SCHACHT, T. (2012): “Surface Reconnaissance in the Persepolis Plain (2005-2008). New Data on the City Organisation and Landscape Management”, in G. P. BASELLO–A. V. ROSSI (eds.): Dariosh studies II. Persepolis and its settlements: territorial system and ideology in the Achaemenid state, Napoli: 249-290.

- BOWDEN, H. (2014): Alexander the Great. A very short introduction, Oxford.

- BRIANT, P. (1989): Alejandro Magno de Grecia al Oriente, Madrid.

- —(2002): From Cyrus to Alexander. A history of the Persian Empire, Indiana.

- —(2010): Alexander the Great and his empire, a short introduction, Oxford.

- —(2015): Darius. In the shadow of Alexander, Harvard.

- BROSIUS, M. (2003): “Alexander and the Persians”, in J. ROISMAN (ed.): Brill ́s companion to Alexander the Great, Boston: 169-193.

- CAHILL, N. (1985): “The treasury at Persepolis: gift-giving at the city of the Persians”, AJA 89.3: 373-389.

- CARTLEDGE, P. (2009): Alejandro Magno; la búsqueda de un pasado desconocido, Barcelona.

- CAWKWELL, G. (1969): “The crowning of Demosthenes”, CQ 19.1: 163-180.

- CIANCAGLINI, C. (1996): “Alessandro e l’incendio di Persepoli nelle tradizioni greca e iranica”, in A. VALVO (ed.): La diffusione dell ́eredità classica nell ́età tardoantica e medievale, forme e modi di trasmissione, Trieste: 59-81.

- COHEN, G. (2015): “Polis hellenis”,in P. WHEATLEY–E.BAYNHAM (eds.): East and West in the world empire of Alexander; essays in honour of Brian Bosworth, Oxford: 259-276.

- DOMÍNGUEZ MONEDERO, A. J. (2013): Alejandro Magno, rey de Macedonia y de Asia, Madrid.

- —(2016): “Alejandro Magno y las ciudades griegas de Asia Menor: entre conquista y liberación”, en F. J. GÓMEZ ESPELOSÍN–B-ANTELA-BERNÁNDEZ (eds.): El imperio de Alejandro: Aspectos geográficos e historiográficos, Alcalá de Henares: 75-115.

- ENGELS, D. (1978): Alexander the Great and the logistics of the Macedonian army, California.

- —(1980): “Alexander’s intelligence system”, CQ 30.2: 327-340.

- FARAGUNA, M. (2003): “Alexander and the Greeks”, in J. ROISMAN (ed.): Brill ́s companion to Alexander the Great, Leiden–Boston: 99-130.

- FLOWER, M. (2000): “Alexander the Great and Panhellenism”, in B. BOSWORTH–E. BAYNHAM (eds.): Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction, New York: 96-135.

- FREDRICKSMEYER, E. (2000): “Alexander the Great and the Kingship of Asia”, in B. BOSWORTH–E. BAYNHAM (eds.): Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction, New York: 136-166.

- FYRE, R. (1993): “Iranian identity in ancient times”, IA 26: 143-146.

- GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ, M. (2008): “Persépolis, ¿Arquitectura celestial o terrenal?”, Historiae 5: 11-25.

- GARIBOLDI, A. (2012): “La circolazione della moneta imperiale achemenide”, in G. P. BASELLO–A. V. ROSSI(eds.): Dariosh studies II. Persepolis and its settlements: territorial system and ideology in the achaemenid state, Napoli: 339-364.

- GEHRKE, H, J. (1996): Alexander der Große, München.

- GÓMEZ ESPELOSÍN, F. J. (2007): La leyenda de Alejandro; mito, historiografía y propaganda, Alcalá de Henares.

- —(2015): En busca de Alejandro; historia de una obsesión, Alcalá de Henares.

- —(2016): “Una geografía de la confusión: ignorancias, interferencias y contradicciones”, in F. J. GÓMEZ ESPELOSÍN–B. Antela-Bernández (eds.): El imperio de Alejandro; aspectos geográficos e historiográficos, Alcalá de Henares: 29-50.

- GREEN, P. (1992): Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B. C. A historical biography, California.

- HAMILTON, J. (1973): Alexander the Great, Pittsburgh.

- HAMMOND, N. G. L. (1992): “The archeological and literary evidence for the burning of the Persepolis palace”, CQ 42.2: 358-364.

- —(2004): El genio de Alejandro Magno, Barcelona.

- HATZOPOULOS, M. (1997): “Alexandre en Perse: la revancha et l ́empire”, ZPE 116: 41-52.

- HECKEL, W. (1980): “Alexander at the Persian Gates”, Athenaeum 58: 168-174.

- —(2010): Las conquista de Alejandro Magno, Madrid.

- HOLT, F. (2016): The treasures of Alexander the Great, New York.

- HOWE, T. (2015): “Introducing Ptolemy: Alexander and the Persian Gates”, in W. HECKEL–S. MÜLLER–GWRIGHTSON (eds.): The many faces of war in the Ancient World, Newcastle: 166-195.

- KAWAMI, T. (1986): “Greek art and persian taste: some animal sculptures from Persepolis”, AJA 90.3: 259-267.

- LANE FOX, R. (2007): Alejandro Magno; conquistador del mundo, Barcelona.

- LAUFFER, S. (2004): Alexander der Große, München.

- LLEWELLYN-JONES, L. (2013): King and court in Ancient Persia 559 to 331 B. C. E., Edinburgh.

- MITCHEL, F. (1965): “Athens in the age of Alexander”, G&R 12.2: 189-204.

- MORRISON, G. (2001): “Alexander, combat psychology, and Persepolis”, Antichthon 35: 30-44.

- MOUSAVI, A. (2012): Persepolis. Discovery and afterlife of a world wonder, Berlin.

- MÜLLER, S. (2003): Mabtnahmen der Herrschaftssicherung gegenüber der makedonischen Opposition bei Alexander dem Brobíen, Frankfurt am Main.

- —(2016): “Arrian, the second sophistic, Xerxes, and the statues of Harmodios and Aristogeiton”, in R. ROLLINGER–S.SVARD (eds.): Cross-cultural Studies in Near Eastern History and Literature, Münster: 173-202.

- NAWOTKA, K (2003): “Alexander the Great in Persepolis”, AAntHung 43: 67-76.

- —(2010): Alexander the Great, Newcastle.

- NENCI, G. (1992): “L’imitatio alexandri”, Polis 4: 173-186.

- O’BRIEN, J. (1992): Alexander the Great: The Invisible Enemy, London.

- PIRAS, A. (2012): “Ethnography of Communication in Achaemenid Iran: The Royal Correspondence”, in P. BASELLO–A.V. ROSSI (eds.), Dariosh studies II. Persepolis and its settlements: territorial system and ideology in the achaemenid state, Napoli: 249-290.

- POPE, A (1957): “Persepolis as a ritual city”, AJ 10: 123-130.

- REZAEIAN, F. (2004): Persepolis recreated, Toronto.

- RODRÍGUEZ ADRADOS, F. (2000): “Las imágenes de Alejandro”, in J. ALVAR–J.BLÁZQUEZ (eds.): Alejandro Magno, hombre y mito, Madrid: 15-31.

- RUNG, E. (2016): “The burning of Greek temples by the Persians and Greek war propaganda”, in K. ULANOWSKI (ed.): The religious aspects of war in the Ancient Near East, Greece and Rome, Boston: 166-179.

- SANCISI-WEERDENBURG, H. (1997): “Alexander and Persepolis”, in J. CARLSEN–B. DUE–O.STEEN DUE–B. POLSEN (eds.): Alexander the Great. Reality and Myth, Roma: 177-188.

- SCHMIDT, E. R. (1953): Persepolis I. Structures, reliefs and inscriptions, Chicago.

- —(1957): Persepolis II. Contents of the treasury and other discoveries, Chicago.

- —(1971): Persepolis III. The royal tombs and other monuments, Chicago.

- SEIBERT, J. (1998): “‘Panhellenischer’Kreuzzug, Nationalkrieg, Rachefeldzug oder makedonischer Eroberungskrieg? Überlegungen zu den Ursachen des Krieges gegen Persien”, in W.WILL (ed.): Alexander der Große, Bonn: 5-58.

- —(2003/2004): “Die Hauptstadt des Perserreiches unter den Achaimeniden: Ständiger Regierungssitz ode rein “Herrscher auf Achse”“, Iranistik 3/4: 21-61.

- SHAHBAZI, A. (1976): “The Persepolis ‘Treasury Reliefs’: once more”, AMI 9: 131-150.

- —(1977): “From Pārsa to Taxt-e Jamshīd”, AMI 13: 197-207.

- —(1978): “New aspects of the persepolitan studies”, Gymnasium 85.6: 487-500.

- —(2003): “Iranians and Alexander”, AJAH 2: 5-38.

- SPECK, H. (2002): “Alexander at the Persian Gates: A Study in Historiography and Topography”, AJAH 1: 7-208.

- SPENCER, K. (2002): The Roman Alexander; reading a cultural myth, Exeter.

- STOTT, G. (1938): “Persepolis”, G&R 7.20: 65-75.

- STRONACH, D. (1963): “Excavations at Pasargadae: First Preliminary Report”, Iran 1: 19-42.

- —(1997): “Anshan and Parsa: Early Achaemenid history, art and architecture on the Iranian plateau”, in J. CURTIS (ed.): Mesopotamia and Iran in the Persian Period: Conquest and Imperialism 539-331 BC, London: 35-53.

- SUMNER, W. M. (2003): Early Urban Life in the Land of Anshan: Excavations at Tal-e Malyan in the Highlands of Iran, Pennsylvania.

- TARN, W. W. (1948): Alexander the Great. 2 vols, Cambridge.

- WATERS, M. (2004): “Cyrus and the Achemenids”, Iran 42: 91-102.

- WEIMER, H. U. (2005): Alexander der Große, München.

- WHEELER, R. (1968): Flames over Persepolis: turning point in history, New York.

Originally published by Karanos: Bulleting of Ancient Macedonian Studies 4 (2021, 13-33) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.