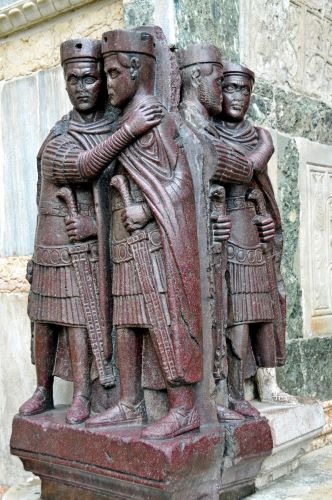

The Romans were a warrior people from very early on.

By Dr. Christopher Brooks

Professor of History

Portland Community College

Introduction

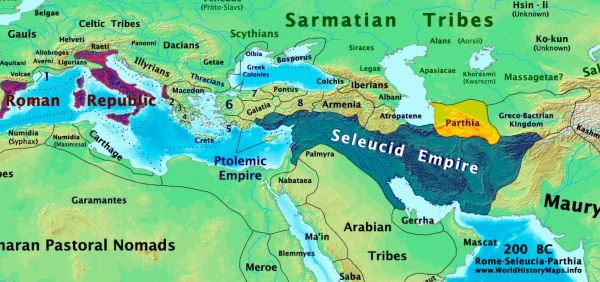

In many ways, Rome defines Western Civilization. Even more so than Greece, the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire that followed created the idea of a single, united civilization sharing certain attributes and providing a lasting intellectual and political legacy. Its boundaries, from what is today England to Turkey and from Germany to Spain, mark out the heartland of what its inhabitants would later consider itself to be “The West” in so many words. The Greek intellectual legacy was eagerly taken up by the Romans and combined with unprecedented organization and engineering on a scale the Greeks had never imagined, even under Alexander the Great.

Roman Origins

Rome was originally a town built amidst seven hills surrounded by swamps in central Italy. The Romans were just one group of “Latins,” central Italians who spoke closely-related dialects of the Latin language. Rome itself had a few key geographical advantages. Its hills were easily defensible, making it difficult for invaders to carry out a successful attack. It was at the intersection of trade routes, thanks in part to its proximity to a natural ford (a shallow part of a river that can be crossed on foot) in the Tiber River, leading to a prosperous commercial and mercantile sector that provided the wealth for early expansion. It also lay on the route between the Greek colonies of southern Italy and various Italian cultures in the central and northern part of the peninsula.

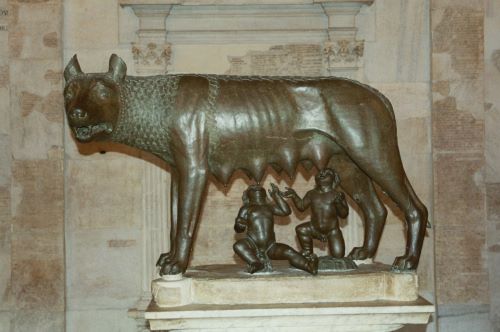

The legend that the Romans themselves invented about their own origins had to do with two brothers: Romulus and Remus. In the legend of Romulus and Remus, two boys were born to a Latin king, but then kidnapped and thrown into the Tiber River by the king’s jealous brother. They were discovered by a female wolf and suckled by her, eventually growing up and exacting their revenge on their treacherous uncle. They then fought each other, with Romulus killing Remus and founding the city of Rome. According to the story, the city of Rome was founded on April 21, 753 BCE. This legend is just that: a legend. Its importance is that it speaks to how the Romans wanted to see themselves, as the descendants of a great man who seized his birthright through force and power, accepting no equals. In a sense, the Romans were proud to believe that their ancient heritage involved being literally raised by wolves.

The Romans were a warrior people from very early on, feuding and fighting with their neighbors and with raiders from the north. They were allied with and, for a time, ruled by a neighboring people called the Etruscans who lived to the northwest of Rome. The Etruscans were active trading partners with the Greek poleis of the south, and Rome became a key link along the Etruscan – Greek trade route. The Etruscans ruled a loose empire of allied city-states that carried on a brisk trade with the Greeks, trading Italian iron for various luxury goods. This mixing of cultures, Etruscan, Greek, and Latin, included shared mythologies and stories. The Greek gods and myths were shared by the Romans, with only the names of the gods being changed (e.g. Zeus became Jupiter, Aphrodite became Venus, Hades became Pluto, etc.). In this way, the Romans became part of the larger Mediterranean world of which the Greeks were such a significant part.

According to Roman legends, the Etruscans ruled the Romans from some time in the eighth century BCE until 509 BCE. During that time, the Etruscans organized them to fight along Greek lines as a phalanx. From the phalanx, the Romans would eventually create new forms of military organization and tactics that would overwhelm the Greeks themselves (albeit hundreds of years later). There is no actual evidence that the Etruscans ruled Rome, but as with the legend of Romulus and Remus, the story of early Etruscan rule inspired the Romans to think of themselves in certain ways – most obviously in utterly rejecting foreign rule of any kind, and even of foreign cultural influence. Romans were always fiercely proud (to the point of belligerence) of their heritage and identity.

By 600 BCE the Romans had drained the swamp in the middle of their territory and built the first of their large public buildings. As noted, they were a monarchy at the time, ruled by (possibly) Etruscan kings, but with powerful Romans serving as advisers in an elected senate. Native-born men rich enough to afford weapons were allowed to vote, while native-born men who were poor were considered full Romans but had no vote. In 509 BCE (according to their own legends), the Romans overthrew the last Etruscan king and established a full Republican form of government, with elected senators making all of the important political decisions. Roman antipathy to kings was so great that no Roman leader would ever call himself Rex – king – even after the Republic was eventually overthrown centuries later.

Note: The Celts

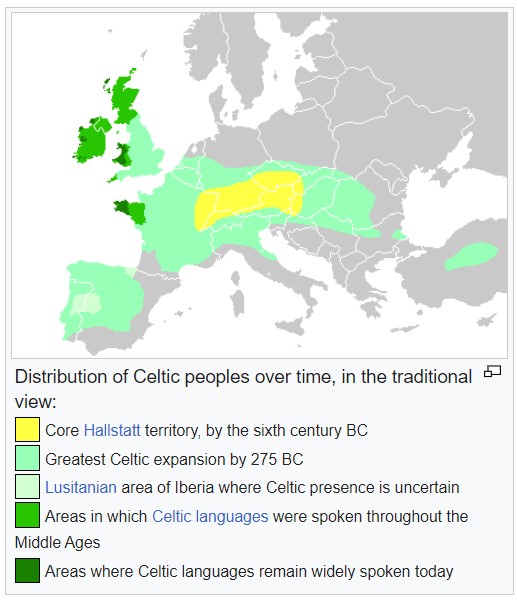

While the Hellenistic world was flourishing in Greece and the Middle East, and Rome was beginning its long climb from obscurity to power, most of Western Europe was dominated by the Celts. The Celts provide background context to the rise of Rome, since Roman expansion would eventually spell the end of Celtic independence in most of Europe.

Much less is known about the Celts than about the contemporaneous cultures of the Mediterranean because the Celts did not leave a written record. The Celts were not a unified empire of any kind; they were a tribal people who shared a common culture and a set of beliefs, along with certain technologies having to do with metal-working and agriculture.

The Celts were a warrior society which seemed to have practiced a variation of what would later be known as feudal law, in which every offense demanded retribution in the former of either violence or “man gold”: the payment needed to atone for a crime and thereby prevent the escalation of violence. The Celts were in contact with the people of the Mediterranean world from as early as 800 BCE, mostly through trade. They lived in fortified towns and were as quick to raid as to trade with their neighbors.

By about 450 BCE the Celts expanded dramatically across Europe. They seem to have become more warlike and expansionist and they adopted a number of technologies already in use further south, including chariot warfare and currency. By 400 BCE groups of Celts began to raid further into “civilized” lands, sacking Rome itself in 387 BCE and pushing into the Hellenistic lands of Macedonia, Greece, and Anatolia. Subsequently, Celtic raiders tended to settle by about 200 BCE, often forming distinct smaller kingdoms within larger lands, such as the region called Galatia in Anatolia, and serving as mercenary warriors for the Hellenistic kingdoms.

Eventually, when the Romans began to expand beyond Italy itself, it was the Celts who were first conquered and then assimilated into the Republic. The Romans regarded Celts as barbarians, but they were thought to be barbarians who were at least capable of assimilating and adopting “true” civilization from the Romans. Centuries later, the descendants of conquered Celts considered themselves fully Roman: speaking Latin as their native language, wearing togas, drinking wine, and serving in the Roman armies.

The Republic

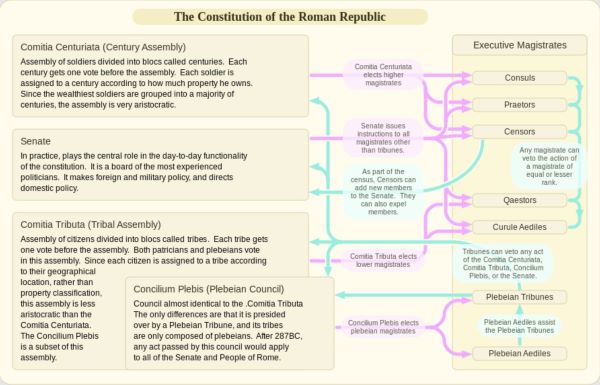

The Roman Republic had a fairly complex system of government and representation, but it was one that would last about 500 years and preside over the vast expansion of Roman power. An assembly, called the Centuriate Assembly, was elected by the citizens and created laws. Each year, the assembly elected two executives called consuls to oversee the laws and ensure their enforcement. The consuls had almost unlimited power, known as imperium, including the right to inflict the death penalty on law-breakers, and they were preceded everywhere by twelve bodyguards called lictors. Consular authority was, however, limited by the fact that the terms were only a year long and each consul was expected to hold the other in check if necessary. Under the consuls there was the Senate, essentially a large body of aristocratic administrators, appointed for life, who controlled state finances. The whole system was tied closely to the priesthoods of the Roman gods, who performed divinations and blessings on behalf of the city. While the Romans were deeply suspicious of individuals who seemed to be trying to take power themselves, several influential families worked behind the scenes to ensure that they could control voting blocks in the Centuriate Assembly and the Senate.

When Rome faced a major crisis, the Centuriate Assembly could vote to appoint a dictator, a single man vested with the full power of imperium. Symbolically, all twenty-four of the lictors would accompany the dictator, who was supposed to use his almost-unlimited power to save Rome from whatever threatened it, then step down and return things to normal. While the office of dictator could have easily led to an attempted takeover, for hundreds of years very few dictators abused their powers and instead respected the temporary nature of Roman dictatorship itself.

The rich were referred to as patricians, families with ancient roots in Rome who occupied most of the positions of the senate and the judiciary in the city. There were about one hundred patrician families, descending from the men Romulus had, allegedly, appointed to the first senate. They were allied with other rich and powerful people, owners of large tracts of land, in trying to hold in check the plebeians, Roman citizens not from patrician backgrounds.

While the Senate began as an advisory body, it later wrested real law-making power from the consuls (who were, after all, almost always drawn from its members). By 133 BCE, the Senate proposed legislation and could veto the legislation of the consuls. An even more important power was its ability to designate funds for war and public building, giving it enormous power over what the Roman government actually did, since the senate could simply cut off funding to projects it disagreed with.The Centuriate Assembly was divided into five different classes based on wealth (a system that ensured that the wealthy could always outvote the poorer). The wealthiest class consisted of the equestrians, so named because they could afford horses and thus form the Roman cavalry; the equestrian class would go on to be a leading power bloc in Roman history well into the Imperial period. The Centuriate Assembly voted on the consuls each year, declared war and peace, and acted as a court of appeal in legal cases involving the death penalty. It could also propose legislation, but the Senate had to approve it for it to become law.

Class Struggle

Rome struggled with a situation analogous to that of Athens, in which the rich not only had a virtual monopoly on political power, but in many cases had the legal right to either enslave or at least extract labor from debtors. In Rome’s case, an ongoing class struggle called the Conflict of Orders took place from about 500 BCE to 360 BCE (140 years!), in which the plebeians struggled to get more political representation. In 494 BCE, the plebeians threatened to simply leave Rome, rendering it almost defenseless, and the Senate responded by allowing the creation of two officials called Tribunes, men drawn from the plebeians who had the legal power to veto certain decisions made by the Senate and consuls. Later, the government created a Plebeian Council to represent the needs of the plebeians, approved the right to marry between patricians and plebeians, banned debt slavery, and finally, came to the agreement that of the two consuls elected each year, one had to be a plebeian. By 287 BCE, the Plebeian Assembly could pass legislation with the weight of law as well.

Roman soldiers were citizen-soldiers, farmers who volunteered to fight for Rome in hopes of being rewarded with wealth taken from defeated enemies. An important political breakthrough happened in about 350 BCE when the Romans enacted a law that limited the amount of land that could be given to a single citizen after a victory, ensuring a more equitable distribution of land to plebeian soldiers. This was a huge incentive to serve in the Roman army, since any soldier now had the potential to become very rich if he participated in a successful campaign against Rome’s enemies.

That being said, class struggle was always a factor in Roman politics. Even after the plebeians gained legal concessions, the rich always held the upper hand because wealthy plebeians would regularly join with patricians to out-vote poorer plebeians. Likewise, in the Centuriate Assembly, the richer classes had the legal right to out-vote the poorer classes – the equestrians and patricians often worked together against the demands of the poorer classes. Practically speaking, by the early third century BCE the plebeians had won meaningful legal rights, namely the right to representation and lawmaking, but those victories were often overshadowed by the fact that wealthy plebeians increasingly joined with the existing patricians to create something new: the Roman aristocracy. Most state offices did not pay salaries, so only those with substantial incomes from land (or from loot won in campaigns) could afford to serve as full-time representatives, officials, or judges – that, too, fed into the political power of the aristocracy over common citizens.

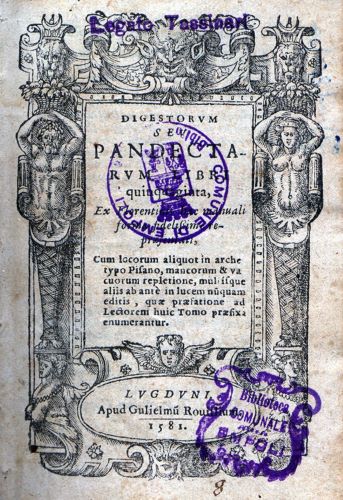

In the midst of this ongoing struggle, the Romans came up with the basis of Roman law, the system of law that, through various iterations, would become the basis for most systems of law still in use in Europe today (Britain being a notable exception). Private law governed disputes between individuals (e.g. property suits, disputes between business partners), while public law governed disputes between individuals and the government (e.g. violent crimes that were seen as a threat to the social order as a whole). In addition, the Romans established the Law of Nations to govern the territories it started to conquer in Italy; it was an early form of international law based on what were believed to be universal standards of justice.

The plebeians had been concerned that legal decisions would always favor the patricians, who had a monopoly on legal proceedings, so they insisted that the laws be written down and made publicly available. Thus, in 451 BCE, members of the Roman government wrote the Twelve Tables, lists of the laws available for everyone to see, which were then posted in the Roman Forum in the center of Rome. Just as it was done in Athens a hundred years earlier, having the laws publicly available reduced the chances of corruption. In fact, according to a Roman legend, the ten men who were charged with recording the laws were sent to Athens to study the laws of Solon of Athens; this was a deliberate use or “copy” of his idea.

Roman Expansion

Roman expansion began with its leadership of a confederation of allied cities, the Latin League. Rome led this coalition against nearby hill tribes that had periodically raided the area, then against the Etruscans that had once ruled Rome itself. Just as the Romans started to consider further territorial expansion, a fierce raiding band of Celts swooped in and sacked Rome in 389 BCE, a setback that took several decades to recover from. In the aftermath, the Romans swore to never let the city fall victim to an attack again.

A key moment in the early period of Roman expansion was in 338 BCE when Rome defeated its erstwhile allies in the Latin League. Rome did not punish the cities after it defeated them, however. Instead, it offered them citizenship in its republic (albeit without voting rights) in return for pledges of loyalty and troops during wartime, a very important precedent because it meant that with every victory, Rome could potentially expand its military might. Soon, the elites of the Latin cities realized the benefits of playing along with the Romans. They were dealt into the wealth distributed after military victories and could play an active role in politics so long as they remained loyal, whereas resisters were eventually ground down and defeated with only their pride to show for it. While Rome would rarely extend actual citizenship to whole communities in the future, the assimilation of the Latins into the Roman state did set an important precedent: conquered peoples could be won over to Roman rule and contribute to Roman power, a key factor in Rome’s ongoing expansion from that point forward.

Rome rapidly expanded to encompass all of Italy except the southernmost regions. Those regions, populated largely by Greeks who had founded colonies there centuries before, invited a Greek warrior-king named Pyrrhus to aid them against the Romans around 280 BCE (Pyrrhus was a Hellenistic king who had already wrested control of a good-sized swath of Greece from the Antigonid dynasty back in Greece). Pyrrhus won two major battles against the Romans, but in the process he lost two-thirds of his troops. After his victories, he made a comment that “one more such victory will undo me” – this led to the phrase “pyrrhic victory,” which means a temporary victory that ultimately spells defeat, or winning the battle but losing the war. He took his remaining troops and returned to Greece. After he fled, the south was unable to mount much of a resistance, and all of Italy was under Roman control by 263 BCE.

Roman Militarism

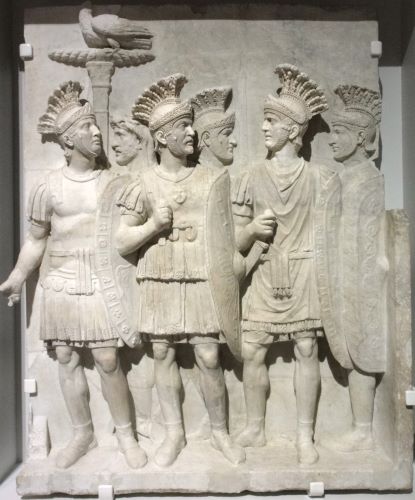

It is important to emphasize the extreme militarism and terrible brutality of Rome during the republican period, very much including this early phase in which it began to acquire its empire. Wars were annual: with very few exceptions over the centuries the Roman legions would march forth to conquer new territory every single year. The Romans swiftly acquired a reputation for absolute ruthlessness and even wanton cruelty, raping and/or slaughtering the civilian inhabitants of conquered cities, enslaving thousands, and in some cases utterly wiping out whole populations (the neighboring city of Veii was obliterated in roughly 393 BCE, for example, right at the start of the conquest period). The Greek historian Polybius calmly noted at the time in his sweeping history of the republic that insofar as there was a deliberate intention behind all of this cruelty, it was easy to identify: causing terror.

Roman soldiers were inspired by straightforward greed as well as the tremendous cultural importance placed on winning military glory. Nothing was as important to a male Roman citizen than his reputation as a soldier. Likewise, Roman aristocrats all acquired their political power through military glory until late in the republic, and even then military glory was all but required for a man to achieve any kind of political importance. The greatest honor a Roman could win was a triumph, a military parade displaying the spoils of war to the cheers of the people of Rome; many people held important positions in Rome, but only the greatest generals were ever rewarded with a triumph.

The overall picture of Roman culture is of a society that was in its own way as fanatical and obsessed with war as was Sparta during the height of its barracks society. Unlike Sparta, however, Rome was able to mobilize gigantic armies, partly because slaves came to perform most of the work on farms and workshops over time, freeing up free Roman men to participate in the annual invasions of neighboring territories. One prominent contemporary historian of Rome, W.V. Harris, wisely warns against the temptation of “power worship” when studying Roman history. Rome did indeed accomplish remarkable things, but it did so through appalling cruelty and astonishing levels of violence.

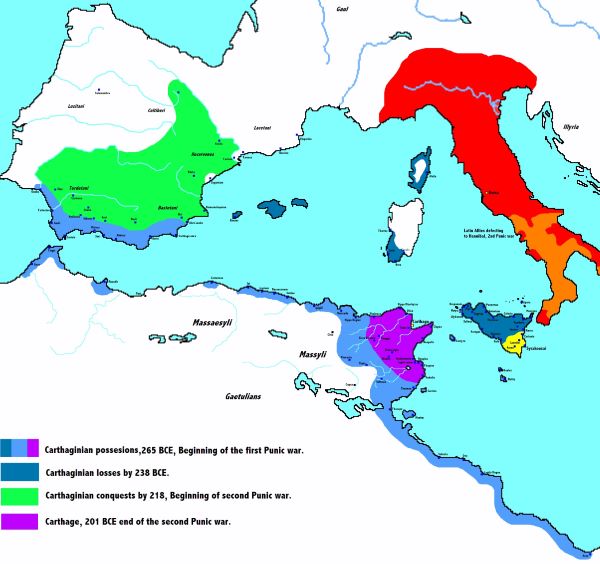

The Punic Wars

Rome’s great rival in this early period of expansion was the North-African city of Carthage, founded centuries earlier by Phoenician colonists. Carthage was one of the richest and most powerful trading empires of the Hellenistic Age, a peer of the Alexandrian empires to the east, trading with them and occasionally skirmishing with the Ptolemaic armies of Egypt and with the Greek cities of Sicily. Rome and Carthage had long been trading partners, and for centuries there was no real reason for them to be enemies since they were separated by the Mediterranean. That being said, as Rome’s power increased to encompass all of Italy, the Carthaginians became increasingly concerned that Rome might pose a threat to its own dominance.

Conflict finally broke out in 264 BCE in Sicily. The island of Sicily was one of the oldest and most important areas for Greek colonization. There, a war broke out between the two most powerful poleis, Syracuse and Messina. The Carthaginians sent a fleet to intervene on behalf of Messinans, but the Messinans then called for help from Rome as well (a betrayal of sorts from the perspective of Carthage). Soon, the conflict escalated as Carthage took the side of Syracuse and Rome saw an opportunity to expand Roman power in Sicily. The Centuriate Assembly voted to escalate the Roman military commitment since its members wanted the potential riches to be won in war. This initiated the First Punic War, which lasted from 264 to 241 BCE. (Note: “Punic” refers to the Roman term for Phoenician, and hence Carthage and its civilization.)

The Romans suffered several defeats, but they were rich and powerful enough at this point to persist in the war effort. Rome benefited greatly from the fact that the Carthaginians did not realize that the war could grow to be about more than just Sicily; even after winning victories there, the Carthaginians never tried to invade Italy itself (which they could have done, at least early on). The Romans eventually learned how to carry out effective naval warfare and stranded the Carthaginian army in Sicily. The Carthaginians sued for peace in 241 BCE and agreed to give up their claims to Sicily and to pay a war indemnity. The Romans, however, betrayed them and seized the islands of Corsica and Sardinia as well, territories that were still under the nominal control of Carthage.

From the aftermath of the First Punic War and the seizure of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica emerged the Roman provincial system: the islands were turned into “provinces” of the Republic, each of which was obligated to pay tribute (the “tithe,” meaning tenth, of all grain) and follow the orders of Roman governors appointed by the senate. That system would continue for the rest of the republican and imperial periods of Roman history, with the governors wielding enormous power and influence in their respective provinces.

Unsurprisingly, the Carthaginians wanted revenge, not just for their loss in the war but for Rome’s seizure of Corsica and Sardinia. For twenty years, the Carthaginians built up their forces and their resources, most notably by invading and conquering a large section of Spain, containing rich mines of gold and copper and thousands of Spanish Celts who came to serve as mercenaries in the Carthaginian armies. In 218 BCE, the great Carthaginian general Hannibal (son of the most successful general who had fought the Romans in the First Punic War) launched a surprise attack in Spain against Roman allies and then against Roman forces themselves. This led to the Second Punic War (218 BCE – 202 BCE).

Hannibal crossed the Alps into Italy from Spain with 60,000 men and a few dozen war elephants (most of the elephants perished, but the survivors proved very effective, and terrifying, against the Roman forces). For the next two years, he crushed every Roman army sent against him, killing tens of thousands of Roman soldiers and marching perilously close to Rome. Hannibal never lost a single battle in Italy, yet neither did he force the Romans to sue for peace.

Hannibal defeated the Romans repeatedly with clever tactics: he lured them across icy rivers and ambushed them, he concealed a whole army in the fog one morning and then sprang on a Roman legion, and he led the Romans into narrow passes and slaughtered them. In one battle in 216 BCE, Hannibal’s smaller army defeated a larger Roman force by letting it push in the Carthaginian center, then surrounding it with cavalry. He was hampered, though, by the fact that he did not have a siege train to attack Rome itself (which was heavily fortified), and he failed to win over the southern Italian cities which had been conquered by the Romans a century earlier. The Romans kept losing to Hannibal, but they were largely successful in keeping Hannibal from receiving reinforcements from Spain and Africa, slowly but steadily weakening his forces.

Eventually, the Romans altered their tactics and launched a guerrilla war against Hannibal within Italy, harrying his forces. This was totally contrary to their usual tactics, and the dictator Fabius Maximus who insisted on it in 217 BCE was mockingly nicknamed “the Delayer” by his detractors in the Roman government despite his evident success. The Romans vacillated on this strategy, suffering the terrible defeat mentioned above in 216 BCE, but as Hannibal’s victories grew and some cities in Italy and Sicily started defecting to the Carthaginian side, they returned to it.

A brilliant Roman general named Scipio defeated the Carthaginian forces back in Spain in 207 BCE, cutting Hannibal off from both reinforcements and supplies, which weakened his army significantly. Scipio then attacked Africa itself, forcing Carthage to recall Hannibal to protect the city. Hannibal finally lost in 202 BCE after coming as close as anyone had to defeating the Romans. The victorious Scipio, now easily the most powerful man in Rome, became the first great general to add to his own name the name of the place he conquered: he became Scipio “Africanus” – conqueror of Africa.

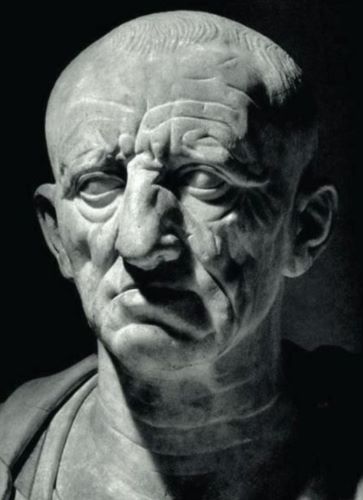

An uneasy peace lasted for several decades between Rome and Carthage, despite enduring anti-Carthaginian hatred in Rome; one prominent senator named Cato the Elder reputedly ended every speech in the Senate with the statement “…and Carthage must be destroyed.” Rome finally forced the issue in the mid-second century BCE by meddling in Carthaginian affairs. The third and last Punic War that ensued was utterly one-sided: it began in 149 BCE, and by 146 BCE Carthage was defeated. Not only were thousands of the Carthaginian people killed or enslaved, but the city itself was brutally sacked (the comment by Polybius regarding the terror inspired by Rome, noted above, was specifically in reference to the horrific sack of Carthage). The Romans created a myth to commemorate their victory, claiming that they had “plowed the earth with salt” at Carthage so that nothing would ever grow there again – that was not literally true, but it did serve as a useful legend as the Romans expanded their territories even further.

Greece

Rome expanded eastward during the same period, eventually conquering all of Greece, the heartland of the culture the Romans so admired and emulated. While Hannibal was busy rampaging around Italy, the Macedonian King Philip V allied with Carthage against Rome, a reasonable decision at the time because it seemed likely that Rome was going to lose the war. In 201 BCE, after the defeat of the Carthaginians, Rome sent an army against Philip to defend the independence of Greece and to exact revenge. There, Philip and the king of the Seleucid empire (named Antiochus III) had agreed to divide up the eastern Mediterranean, assuming they could defeat and control all of the Greek poleis. An expansionist faction in the Roman senate successfully convinced the Centuriate Assembly to declare war. The Roman legions defeated the Macedonian forces without much trouble in 196 BCE and then, perhaps surprisingly, they left, having accomplished their stated goal of defending Greek independence. Rome continued to fight the Seleucids for several more years, however, finally reducing the Seleucid king Antiochus III to a puppet of Rome.

Despite having no initial interest in establishing direct control in Greece, the Romans found that rival Greek poleis clamored for Roman help in their conflicts, and Roman influence in the region grew. Even given Rome’s long standing admiration for Greek culture, the political and military developments of this period, from 196 – 168 BCE, helped confirm the Roman belief that the Greeks were artistic and philosophical geniuses but, at least in their present iteration, were also conniving, treacherous, and lousy at political organization. There was also a growing conservative faction in Rome led by Cato the Elder that emphatically emphasized Roman moral virtue over Greek weakness.

Philip V’s son Perseus took the throne of Macedon in 179 BCE and, while not directly threatening Roman power, managed to spark suspicion among the Roman elite simply by reasserting Macedonian sovereignty in the region. In 172 BCE Rome sent an army and Macedon was defeated in 168 BCE. Rome split Macedon into puppet republics, plundered Macedon’s allies, and lorded over the remaining Greek poleis. Revolts in 150 and 146 against Roman power served as the final pretext for the Roman subjugation of Greece. This time, the Romans enacted harsh penalties for disloyalty among the Greek cities, utterly destroying the rich city of Corinth and butchering or enslaving tens of thousands of Greeks for siding against Rome. The plunder from Corinth specifically also sparked great interest in Greek art among elite Romans, boosting the development of Greco-Roman artistic traditions back in Italy.

Thus, after centuries of warfare, by 140 BCE the Romans controlled almost the entire Mediterranean world, from Spain to Anatolia. They had not yet conquered the remaining Hellenistic kingdoms, namely those of the Seleucids in the Near East and the Ptolemies in Egypt, but they controlled a vast territory nonetheless. Even the Ptolemies, the most genuinely independent power in the region, acknowledged that Rome held all the real power in international affairs.

The last great Hellenistic attempt to push back Roman control was in the early first century BCE, with the rise of a Greek king, Mithridates VI, from Pontus, a small kingdom on the southern shore of the Black Sea. Mithridates led a large anti-Roman coalition of Hellenistic peoples first in Anatolia and then in Greece itself starting in 88 BCE. Mithridates was seen by his followers as a great liberator from Roman corruption (one Roman governor had molten gold poured down his throat to symbolize the just punishment of Roman greed). He went on to fight a total of three wars against Rome, but despite his tenacity he was finally defeated and killed in 63 BCE, the same year that Rome extinguished the last pitiful vestiges of the Seleucid kingdom.

Under the leadership of a general and politician, Pompey (“the Great”), both Mithridates and the remaining independent formerly Seleucid territories were defeated and incorporated either as provinces or puppet states under the control of the Republic. With that, almost the entire Mediterranean region was under Rome’s sway – Egypt alone remained independent.

Greco-Roman Culture

The Romans had been in contact with Greek culture for centuries, ever since the Etruscans struck up their trading relationship with the Greek poleis of southern Italy. Initially, the Etruscans formed a conduit for trade and cultural exchange, but soon the Romans were trading directly with the Greeks as well as the various Greek colonies all over the Mediterranean. By the time the Romans finally conquered Greece itself, they had already spent hundreds of years absorbing Greek ideas and culture, modeling their architecture on the great buildings of the Greek Classical Age and studying Greek ideas.

Despite their admiration for Greek culture, there was a paradox in that Roman elites had their own self-proclaimed “Roman” virtues, virtues that they attributed to the Roman past, which were quite distinct from Greek ideas. Roman virtues revolved around the idea that a Roman was strong, honest, straightforward, and powerful, while the Greeks were (supposedly) shifty, untrustworthy, and incapable of effective political organization. The simple fact that the Greeks had been unable to forge an empire except during the brief period of Alexander’s conquests seemed to the Romans as proof that they did not possess an equivalent degree of virtue.

The Romans summed up their own virtues with the term Romanitas, which meant to be civilized, to be strong, to be honest, to be a great public speaker, to be a great fighter, and to work within the political structure in alliance with other civilized Romans. There was also a powerful theme of self-sacrifice associated with Romanitas – the ideal Roman would sacrifice himself for the greater good of Rome without hesitation. In some ways, Romanitas was the Romans’ spin on the old Greek combination of arete and civic virtue.

One example of Romanitas in action was the role of dictator. A Roman dictator, even more so than a consul, was expected to embody Romanitas, leading Rome through a period of crisis but then willingly giving up power. Since the Romans were convinced that anything resembling monarchy was politically repulsive, a dictator was expected to serve for the greater good of Rome and then step aside when peace was restored. Indeed, until the first century CE, dictators duly stepped down once their respective crises were addressed.

Romanitas was profoundly compatible with Greek Stoicism (which came of age in the Hellenistic monarchies just as Rome itself was expanding). Stoicism celebrated self-sacrifice, strength, political service, and the rejection of frivolous luxuries; these were all ideas that seemed laudable to Romans. By the first century BCE, Stoicism was the Greek philosophy of choice among many aristocratic Romans (a later Roman emperor, Marcus Aurelius, was even a Stoic philosopher in his own right).

The implications of Romanitas for political and military loyalty and morale are obvious. One less obvious expression of Romanitas, however, was in public building and celebrations. One way for elite (rich) Romans to express their Romanitas was to fund the construction of temples, forums, arenas, or practical public works like roads and aqueducts. Likewise, elite Romans would often pay for huge games and contests with free food and drink, sometimes for entire cities. This practice was not just in the name of showing off; it was an expression of one’s loyalty to the Roman people and their shared Roman culture. The creation of numerous Roman buildings (some of which survive) is the result of this form of Romanitas.

Despite their tremendous pride in Roman culture, the Romans still found much to admire about Greek intellectual achievements. By about 230 BCE, Romans started taking an active interest in Greek literature. Some Greek slaves were true intellectuals who found an important place in Roman society. One status symbol in Rome was to have a Greek slave who could tutor one’s children in the Greek language and Greek learning. In 220 BCE a Roman senator, Quintus Fabius Pictor, wrote a history of Rome in Greek, the first major work of Greek literature written by a Roman (like so many ancient sources, it has not survived). Soon, Romans were imitating the Greeks, writing in both Greek and Latin and creating poetry, drama, and literature.

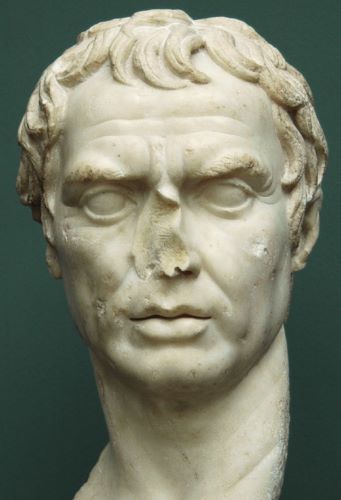

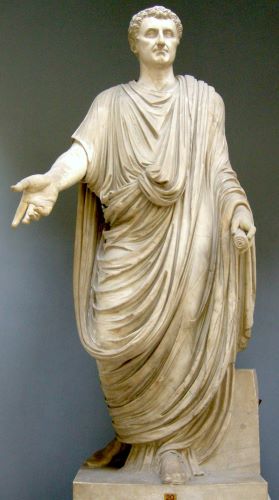

That being noted, the interest in Greek culture was muted until the Roman wars in Greece that began with the defeat of Philip V of Macedon. Rome’s Greek wars created a kind of “feeding frenzy” of Greek art and Greek slaves. Huge amounts of Greek statuary and art were shipped back to Rome as part of the spoils of war, having an immediate impact on Roman taste. The appeal of Greek art was undeniable. Greek artists, even those who escaped slavery, soon started moving to Rome en masse because there was so much money to be made there if an artist could secure a wealthy patron. Greek artists, and the Romans who learned from them, adapted the Hellenistic Greek style. In many cases, classical statues were recreated exactly by sculptors, somewhat like modern-day prints of famous paintings. In others, a new style of realistic portraiture in sculpture that originated in the Hellenistic kingdoms proved irresistible to the Romans; whereas the Greeks of the Classical Age usually idealized the subjects of art, the Romans came to prefer more realistic and “honest” portrayals. We know precisely what many Romans looked like because of the realistic busts made of their faces: wrinkles, warts and all.

Along with philosophy and architecture, the most important Greek import to arrive on Roman shores was rhetoric: the mastery of words and language in order to persuade people and win arguments. The Greeks held that the two ways a man could best his rivals and assert his virtue were battle and public discussion and argumentation. This tradition was felt very keenly by the Romans, because those were precisely the two major ways the Roman Republic operated – the superiority of its armies was well-known, while individual leaders had to be able to convince their peers and rivals of the correctness of their positions. The Romans thus very consciously tried to copy the Greeks, especially the Athenians, for their skill at oratory.

Not surprisingly, the Romans both admired and resented the Greeks for the Greek mastery of words. The Romans came to pride themselves on a more direct, less subtle form of oratory than that (supposedly) practiced in Greece. Part of Roman oratorical skill was the use of passionate appeals to emotional responses in the audience, ones that were supposed to both harness and control the emotions of the speaker himself. The Romans also formalized instruction in rhetoric, a practice of studying the speeches of great speakers and politicians of the past and of debating instructors and fellow students in mock scenarios.

Roman Society

Much of Roman social life revolved around the system of clientage. Clientage consisted of networks of “patrons” – people with power and influence – and their “clients” – those who looked to the patrons for support. A patron would do things like arrange for his or her (i.e. there were women patrons, not just men) clients to receive lucrative government contracts, to be appointed as officers in a Roman legion, to be able to buy a key piece of farmland, and so on. In return, the patron would expect political support from their clients by voting as directed in the Centuriate or Plebeian Assembly, by influencing other votes, and by blocking political rivals. Likewise, clients who shared a patron were expected to help one another. These were open, publicly-known alliances rather than hidden deals made behind closed doors; groups of clients would accompany their patron into meetings of the senate or assemblies as a show of strength.

The government of the late Republic was still in the form of the Plebeian Assembly, the Centuriate Assembly, the Senate, ten tribunes, two consuls, and a court system under formal rules of law. By the late Republic, however, a network of patrons and clients had emerged that largely controlled the government. Elite families of nobles, through their client networks, made all of the important decisions. Beneath this group were the equestrians: families who did not have the ancient lineages of the patricians and who normally did not serve in public office. The equestrians, however, were rich, and they benefited from the fact that senators were formally banned from engaging in commerce as of the late third century BCE. They constituted the business class of Republican Rome who supported the elites while receiving various trade and mercantile concessions.

Meanwhile, the average plebeian had long ago lost his or her representation. The Plebeian Assembly was controlled by wealthy plebeians who were the clients of nobles. In other words, they served the interests of the rich and had little interest in the plight of the class they were supposed to represent. This created an ongoing problem for Rome, one that was exploited many times by populist leaders: Rome relied on a free class of citizens to serve in the army, but those same citizens often had to struggle to make ends meet as farmers. As the rich grew richer, they bought up land and sometimes even forced poorer citizens off of their farms. Thus, there was an existential threat to Rome’s armies, and with it, to Rome itself.

A comparable pattern existed in the territories – soon provinces – conquered in war. Rome was happy to grant citizenship to local elites who supported Roman rule, and sometimes entire communities could be granted citizenship on the basis of their loyalty (or simply their perceived usefulness) to Rome. Citizenship was a useful commodity, protecting its holders from harsher legal punishments and affording them significant political rights. Most Roman subjects, however, were just that: subjects, not citizens. In the provinces they were subject to the goodwill of the Roman governor, who might well look for opportunities to extract provincial wealth for his own benefit.

At the bottom of the Roman social system were the slaves. Slaves were one of the most lucrative forms of loot available to Roman soldiers, and so many lands had been conquered by Rome that the population of the Republic was swollen with slaves. Fully one-third of the population of Italy were slaves by the first century CE. Even freed slaves, called freedmen, had limited legal rights and had formal obligations to serve their former masters as clients. Roman slaves spanned the same range of jobs noted with other slaveholding societies like the Greeks: elite slaves lived much more comfortably than did most free Romans, but most were laborers or domestic servants. All could be abused by their owners without legal consequence.

Slavery was a huge economic engine in Roman society. Much of the “loot” seized in Roman campaigns was made up of human beings, and Roman soldiers were eager to capitalize on captives they took by selling them on returning to Italy. In historical hindsight, however, slavery undermined both Roman productivity and the pace of innovation in Roman society. It simply was not necessary to seek out new and better ways of doing things in the form of technological progress or social innovations because slave labor was always available. While Roman engineering was impressive, Rome developed no new technology to speak of in its thousand-year history. Likewise, the long-term effect of the growth of slavery in Rome was to undermine the social status of free Roman citizens, with farmers in particular struggling to survive as rich Romans purchased land and built huge slave plantations.

There were many slave uprisings, the most significant of which was led by Spartacus, a gladiator (warrior who fought for public amusement) originally from Thrace. Spartacus led the revolt of his gladiatorial school in the Italian city of Capua in 73 BCE. He set up a war camp on the slopes of the volcano Mt. Vesuvius, to which thousands of slaves fled, culminating in an “army” of about 70,000. He tried to convince them to flee over the Alps to seek refuge in their (mostly Celtic) homelands, but was eventually convinced to turn around to plunder Italy. The richest man in Italy, the senator Crassus, took command of the Roman army assembled to defeat Spartacus, crushing the slave army and killing Spartacus in 71 BCE (and lining the road to Rome with 6,000 crucified slaves).

In one area, however, Rome represented greater freedom and autonomy than did some of its neighboring societies (like Greece): gender roles. While Roman culture was explicitly patriarchal, with families organized under the authority of the eldest male of the household (the pater familias), there is a great deal of textual evidence that suggests that women enjoyed considerable independence nevertheless. Women retained the ownership of their dowries at marriage, could initiate divorce, and controlled their own inheritances. Widows, who were common thanks to the young marriage age of women and the death of soldier husbands, were legally autonomous and continued to run households after the death of the husband. Within families, women’s voices carried considerable weight, and in the realm of politics, while men held all official positions, women exercised considerable influence from behind the scenes.

It is easy to overstate women’s empowerment in Roman society; Roman culture celebrated the devoted mother and wife as the female ideal, and Roman traditionalists decried the loosening of strict gender roles that seems to have taken place over time during the Republic. Women were expected to be frugal managers of households and, in theory, they were to avoid ostentatious displays. Likewise, Roman law explicitly designated men as the official decision-makers within the family unit. That being noted, however, one of the reasons that we know that women did enjoy a higher degree of autonomy than in many other societies is the number of surviving texts that both described and, in many cases, celebrated the role of women. Those texts were written by both men and women, and most Romans (men very much included) felt that it was both appropriate and desirable for both boys and girls to be properly educated.

The End of the Republic

The Roman Republic lasted for roughly five centuries. It was under the Republic that Rome evolved from a single town to the heart of an enormous empire. Despite the evident success of the republican system, however, there were inexorable problems that plagued the Republic throughout its history, most evidently the problem of wealth and power. Roman citizens were, by law, supposed to have a stake in the Republic. They took pride in who they were and it was the common patriotic desire to fight and expand the Republic among the citizen-soldiers of the Republic that created, at least in part, such an effective army. At the same time, the vast amount of wealth captured in the military campaigns was frequently siphoned off by elites, who found ways to seize large portions of land and loot with each campaign. By around 100 BCE even the existence of the Plebeian Assembly did almost nothing to mitigate the effect of the debt and poverty that afflicted so many Romans thanks to the power of the clientage networks overseen by powerful noble patrons.

The key factor behind the political stability of the Republic up until the aftermath of the Punic Wars was that there had never been open fighting between elite Romans in the name of political power. In a sense, Roman expansion (and especially the brutal wars against Carthage) had united the Romans; despite their constant political battles within the assemblies and the senate, it had never come to actual bloodshed. Likewise, a very strong component of Romanitas was the idea that political arguments were to be settled with debate and votes, not clubs and knives. Both that unity and that emphasis on peaceful conflict resolution within the Roman state itself began to crumble after the sack of Carthage.

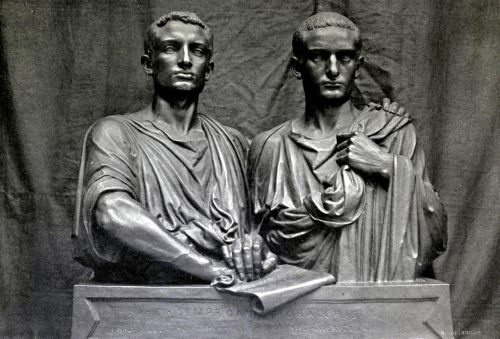

The first step toward violent revolution in the Republic was the work of the Gracchus brothers – remembered historically as the Gracchi (i.e. “Gracchi” is the plural of “Gracchus”). The older of the two was Tiberius Gracchus, a rich but reform-minded politician. Gracchus, among others, was worried that the free, farm-owning common Roman would go extinct if the current trend of rich landowners seizing farms and replacing farmers with slaves continued. Without those commoners, Rome’s armies would be drastically weakened. Thus, he managed to pass a bill through the Centuriate Assembly that would limit the amount of land a single man could own, distributing the excess to the poor. The Senate was horrified and fought bitterly to reverse the bill. Tiberius ran for a second term as tribune, something no one had ever done up to that point, and a group of senators clubbed him to death in 133 BCE.

Tiberius’s brother Gaius Gracchus took up the cause, also becoming tribune. He attacked corruption in the provinces, allying himself with the equestrian class and allowing equestrians to serve on juries that tried corruption cases. He also tried to speed up land redistribution. His most radical move was to try to extend full citizenship to all of Rome’s Italian subjects, which would have effectively transformed the Roman Republic into the Italian Republic. Here, he lost even the support of his former allies in Rome, and he killed himself in 121 BCE rather than be murdered by another gang of killers sent by senators.

The reforms of the Gracchi were temporarily successful: even though they were both killed, the Gracchi’s central effort to redistribute land accomplished its goal. A land commission created by Tiberius remained intact until 118 BCE, by which time it had redistributed huge tracts of land held illegally by the rich. Despite their vociferous opposition, the rich did not suffer much, since the lands in question were “public lands” largely left in the aftermath of the Second Punic War, and normal farmers did enjoy benefits. Likewise, despite Gaius’s death, the Republic eventually granted citizenship to all Italians in 84 BCE, after being forced to put down a revolt in Italy. In hindsight, the historical importance of the Gracchi was less in their reforms and more in the manner of their deaths – for the first time, major Roman politicians had simply been murdered (or killed themselves rather than be murdered) for their politics. It became increasingly obvious that true power was shifting away from rhetoric and toward military might.

A contemporary of the Gracchi, a general named Gaius Marius, took further steps that eroded the traditional Republican system. Marius combined political savvy with effective military leadership. Marius was both a consul (elected an unprecedented seven times) and a general, and he used his power to eliminate the property requirement for membership in the army. This allowed the poor to join the army in return for nothing more than an oath of loyalty, one they swore to their general rather than to the Republic. Marius was popular with Roman commoners because he won consistent victories against enemies in both Africa and Germany, and because he distributed land and farms to his poor soldiers. This made him a people’s hero, and it terrified the nobility in Rome because he was able to bypass the usual Roman political machine and simply pay for his wars himself. His decision to eliminate the property requirement meant that his troops were totally dependent on him for loot and land distribution after campaigns, undermining their allegiance to the Republic.

A general named Sulla followed in Marius’s footsteps by recruiting soldiers directly and using his military power to bypass the government. In the aftermath of the Italian revolt of 88 – 84 BCE, the Assembly took Sulla’s command of Roman legions fighting the Parthians away and gave it to Marius in return for Marius’s support in enfranchising the people of the Italian cities. Sulla promptly marched on Rome with his army, forcing Marius to flee. Soon, however, Sulla left Rome to command legions against the army of the anti-Roman king Mithridates in the east. Marius promptly attacked with an army of his own, seizing Rome and murdering various supporters of Sulla. Marius himself soon died (of old age), but his followers remained united in an anti-Sulla coalition under a friend of Marius, Cinna.

After defeating Mithridates, Sulla returned and a full-scale civil war shook Rome in 83 – 82 BCE. It was horrendously bloody, with some 300,000 men joining the fighting and many thousands killed. After Sulla’s ultimate victory he had thousands of Marius’s supporters executed. In 81 BCE, Sulla was named dictator; he greatly strengthened the power of the Senate at the expense of the Plebeian Assembly, had his enemies in Rome murdered and their property seized, then retired to a life of debauchery in his private estate (and soon died from a disease he contracted). The problem for the Republic was that, even though Sulla ultimately proved that he was loyal to republican institutions, other generals might not be in the future. Sulla could have simply held onto power indefinitely thanks to the personal loyalty of his troops.

Julius Caesar

Thus, there is an unresolved question about the end of the Roman Republic: when a new politician and general named Julius Caesar became increasingly powerful and ultimately began to replace the Republic with an empire, was he merely making good on the threat posed by Marius and Sulla, or was there truly something unprecedented about his actions? Julius Caesar’s rise to power is a complex story that reveals just how murky Roman politics were by the time he became an important political player in about 70 BCE. Caesar himself was both a brilliant general and a shrewd politician; he was skilled at keeping up the appearance of loyalty to Rome’s ancient institutions while exploiting opportunities to advance and enrich himself and his family. He was loyal, in fact, to almost no one, even old friends who had supported him, and he also cynically used the support of the poor for his own gain.

Two powerful politicians, Pompey and Crassus (both of whom had risen to prominence as supporters of Sulla), joined together to crush the slave revolt of Spartacus in 70 BCE and were elected consuls because of their success. Pompey was one of the greatest Roman generals, and he soon left to eliminate piracy from the Mediterranean, to conquer the Jewish kingdom of Judea, and to crush an ongoing revolt in Anatolia. He returned in 67 BCE and asked the Senate to approve land grants to his loyal soldiers for their service, a request that the Senate refused because it feared his power and influence with so many soldiers who were loyal to him instead of the Republic. Pompey reacted by forming an alliance with Crassus and with Julius Caesar, who was a member of an ancient patrician family. This group of three is known in history as the First Triumvirate.

Each member of the Triumvirate wanted something specific: Caesar hungered for glory and wealth and hoped to be appointed to lead Roman armies against the Celts in Western Europe, Crassus wanted to lead armies against Parthia (i.e. the “new” Persian Empire that had long since overthrown Seleucid rule in Persia itself), and Pompey wanted the Senate to authorize land and wealth for his troops. The three of them had so many clients and wielded so much political power that they were able to ratify all of Pompey’s demands, and both Caesar and Crassus received the military commissions they hoped for. Caesar was appointed general of the territory of Gaul (present-day France and Belgium) and he set off to fight an infamous Celtic king named Vercingetorix.

From 58 to 50 BCE, Caesar waged a brutal war against the Celts of Gaul. He was both a merciless combatant, who slaughtered whole villages and enslaved hundreds of thousands of Celts (killing or enslaving over a million people in the end), and a gifted writer who wrote his own accounts of his wars in excellent Latin prose. His forces even invaded England, establishing a Roman territory there that lasted centuries. All of the lands he invaded were so thoroughly conquered that the descendants of the Celts ended up speaking languages based on Latin, like French, rather than their native Celtic dialects.

Caesar’s victories made him famous and immensely powerful, and they ensured the loyalty of his battle-hardened troops. In Rome, senators feared his power and called on Caesar’s former ally Pompey to bring him to heel (Crassus had already died in his ill-considered campaign against the Parthians; his head was used as a prop in a Greek play staged by the Parthian king). Pompey, fearing his former ally’s power, agreed and brought his armies to Rome. The Senate then recalled Caesar after refusing to renew his governorship of Gaul and his military command, or allowing him to run for consul in absentia.

The Senate hoped to use the fact that Caesar had violated the letter of republican law while on campaign to strip him of his authority. Caesar had committed illegal acts, including waging war without authorization from the Senate, but he was protected from prosecution so long as he held an authorized military command. By refusing to renew his command or allow him to run for office as consul, he would be open to charges. His enemies in the Senate feared his tremendous influence with the people of Rome, so the conflict was as much about factional infighting among the senators as fear of Caesar imposing some kind of tyranny.

Caesar knew what awaited him in Rome – charges of sedition against the Republic – so he simply took his army with him and marched off to Rome. In 49 BCE, he dared to cross the Rubicon River in northern Italy, the legal boundary over which no Roman general was allowed to bring his troops; he reputedly announced that “the die is cast” and that he and his men were now committed to either seizing power or facing total defeat. The brilliance of Caesar’s move was that he could pose as the champion of his loyal troops as well as that of the common people of Rome, whom he promised to aid against the corrupt and arrogant senators; he never claimed to be acting for himself, but instead to protect his and his men’s legal rights and to resist the corruption of the Senate.

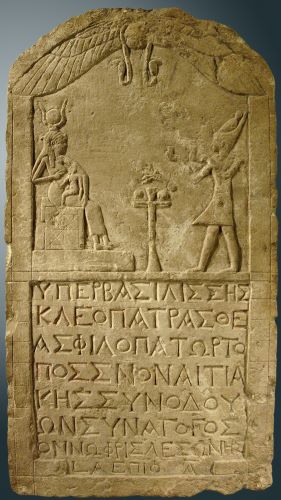

Pompey had been the most powerful man in Rome, both a brilliant general and a gifted politician, but he did not anticipate Caesar’s boldness. Caesar surprised him by marching straight for Rome. Pompey only had two legions, both of whom had served under Caesar in the past and, and he was thus forced to recruit new troops. As Caesar approached, Pompey fled to Greece, but Caesar followed him and defeated his forces in battle in 48 BCE. Pompey himself escaped to Egypt, where he was promptly murdered by agents of the Ptolemaic court who had read the proverbial writing on the wall and knew that Caesar was the new power to contend with in Rome. Subsequently, Caesar came to Egypt and stayed long enough to forge a political alliance, and carry on an affair, with the queen of Egypt: Cleopatra VII, last of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Caesar helped Cleopatra defeat her brother (to whom she was married, in the Egyptian tradition) in a civil war and to seize complete control over the Egyptian state. She also bore him his only son, Caesarion.

Caesar returned to Rome two years later after hunting down Pompey’s remaining loyalists. There, he had himself declared dictator for life and set about creating a new version of the Roman government that answered directly to him. He filled the Senate with his supporters and established military colonies in the lands he had conquered as rewards for his loyal troops (which doubled as guarantors of Roman power in those lands, since veterans and their families would now live there permanently). He established a new calendar, which included the month of “July” named after him, and he regularized Roman currency. Then he promptly set about making plans to launch a massive invasion of Persia.

Instead of leading another glorious military campaign, however, in March of 44 BCE Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators who resented his power and genuinely desired to save the Republic. The result was not the restoration of the Republic, however, just a new chapter in the Caesarian dictatorship. Its architect was Caesar’s heir, his grand-nephew Octavian, to whom Caesar left (much to almost everyone’s shock) almost all of his vast wealth.

Mark Antony and Octavian

Following his death, Caesar’s right-hand man, a skilled general named Mark Antony, joined with Octavian and another general named Lepidus to form the “Second Triumvirate.” In 43 BCE they seized control in Rome and then launched a successful campaign against the old republican loyalists, killing off the men who had killed Caesar and murdering the strongest senators and equestrians who had tried to restore the old institutions. Mark Antony and Octavian soon pushed Lepidus to the side and divided up control of Roman territory – Octavian taking Europe and Mark Antony taking the eastern territories and Egypt. This was an arrangement that was not destined to last; the two men had only been allies for the sake of convenience, and both began scheming as to how they could seize total control of Rome’s vast empire.

Mark Antony moved to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where he set up his court. He followed in Caesar’s footsteps by forging both a political alliance and a romantic relationship with Cleopatra, and the two of them were able to rule the eastern provinces of the Republic in defiance of Octavian. In 34 BCE, Mark Antony and Cleopatra declared that Cleopatra’s son by Julius Caesar, Caesarion, was the heir to Caesar (not Octavian), and that their own twins were to be rulers of Roman provinces. Rumors in the west claimed that Antony was under Cleopatra’s thumb (which is unlikely: the two of them were both savvy politicians and seem to have shared a genuine affection for one another) and was breaking with traditional Roman values, and Octavian seized on this behavior to claim that he was the true protector of Roman morality. Soon, Octavian produced a will that Mark Antony had supposedly written ceding control of Rome to Cleopatra and their children on his death; whether or not the will was authentic, it fit in perfectly with the publicity campaign on Octavian’s part to build support against his former ally in Rome.

When he finally declared war in 32 BCE, Octavian claimed he was only interested in defeating Cleopatra, which led to broader Roman support because it was not immediately stated that it was yet another Roman civil war. Antony and Cleopatra’s forces were already fairly scattered and weak due to a disastrous campaign against the Persians a few years earlier. In 31 BCE, Octavian defeated Mark Antony’s forces, which were poorly equipped, sick, and hungry. Antony and Cleopatra’s soldiers were starved out by a successful blockade engineered by Octavian and his friend and chief commander Agrippa, and the unhappy couple killed themselves the next year in exile. Octavian was 33. As his grand-uncle had before him, Octavian began the process of manipulating the institutions of the Republic to transform it into something else entirely: an empire.

Transition to Empire

One of the peculiar things about the Roman Republic is that its rise to power was in no way inevitable. No Roman leader had a “master plan” to dominate the Mediterranean world, and the Romans of 500 BCE would have been shocked to find Rome ruling over a gigantic territory a few centuries later. Likewise, the demise of the Republic was not inevitable. The class struggles and political rivalries that ultimately led to the rise of Caesar and then to the true transformation brought about by Octavian could have gone very differently. Perhaps the most important thing that Octavian could, and did, do was to recognize that the old system was no longer working the way it should, and he thus set about deliberately creating a new system in its place. For better or for worse, by the time of his death in 14 CE, Octavian had permanently dismantled the Republic and replaced it with the Roman Empire.

When Octavian succeeded in defeating Marc Antony, he removed the last obstacle to his own control of Rome’s vast territories. While paying lip service to the idea that the Republic still survived, he in fact replaced the republican system with one in which a single sovereign ruled over the Roman state. In doing so he founded the Roman Empire, a political entity that would survive for almost five centuries in the west and over a thousand years in the east.

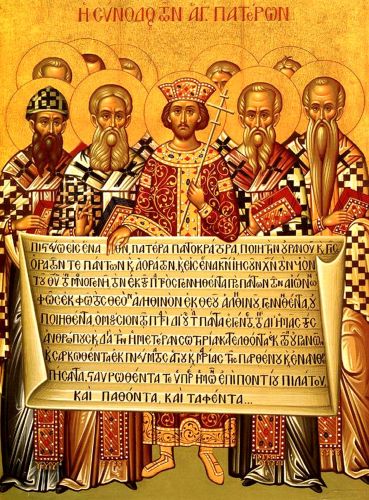

This system was called the Principate, rule by the “First.” Likewise, although “Caesar” had originally simply been the family name of Julius Caesar’s line, “Caesar” came to be synonymous with the emperor himself by the end of the first century CE. The Roman terms for rule would last into the twentieth century CE: the imperial titles of the rulers of both Russia and Germany – “Tsar” and “Kaiser” – meant “Caesar.” In turn, the English word “emperor” derives from imperator, the title of a victorious Roman general in the field, which was adopted as yet another honorific by the Roman emperors. The English word “prince” is another Romanism, from Princeps Civitatis, “First Citizen,” the term that Augustus invented for himself. For the sake of clarity, this article will use the anglicized term “emperor” to refer to all of the leaders of the Roman imperial system.

Augustus

The height of Roman power coincided with the first two hundred years of the Roman Empire, a period that was remembered as the Pax Romana: the Roman Peace. It was possible during the period of the Roman Empire’s height, from about 1 CE to 200 CE, to travel from the Atlantic coast of Spain or Morocco all the way to Mesopotamia using good roads, speaking a common language, and enjoying official protection from banditry. The Roman Empire was as rich, powerful, and glorious as any in history up to that point, but it also represented oppression and imperialism to slaves, poor commoners, and conquered peoples.

Octavian was unquestionably the architect of the Roman Empire. Unlike his great-uncle, Julius Caesar, Octavian eliminated all political rivals and set up a permanent hereditary emperorship. All the while, he claimed to be restoring not just peace and prosperity, but the Republic itself. Since the term Rex (king) would have been odious to his fellow Romans, Augustus instead referred to himself as Princeps Civitatus, meaning “first citizen.” He used the Senate to maintain a facade of republican rule, instructing senators on the actions they were to take; a good example is that the Senate “asked” him to remain consul for life, which he graciously accepted. By 23 BCE, he assumed the position of tribune for life, the position that allowed unlimited power in making or vetoing legislation. All soldiers swore personal oaths of loyalty to him, and having conquered Egypt from his former ally Mark Antony, Augustus was worshiped there as the latest pharaoh. The Senate awarded Octavian the honorific Augustus: “illustrious” or “semi-divine.” It is by that name, Augustus Caesar, that he is best remembered.

Despite his obvious personal power, Augustus found it useful to maintain the facade of the Republic, along with republican values like thrift, honesty, bravery, and honor. He instituted strong moralistic laws that penalized (elite) young men who tried to avoid marriage and he celebrated the piety and loyalty of conservative married women. Even as he converted the government from a republic to a bureaucratic tool of his own will, he insisted on traditional republican beliefs and republican culture. This no doubt reflected his own conservative tastes, but it also eased the transition from republic to autocracy for the traditional Roman elites.

As Augustus’s powers grew, he received an altogether novel legal status, imperium majus, that was something like access to the extraordinary powers of a dictator under the Republic. Combined with his ongoing tribuneship and direct rule over the provinces in which most of the Roman army was garrisoned at the time, Augustus’s practical control of the Roman state was unchecked. As a whole, the legal categories used to explain and excuse the reality of Augustus’s vast powers worked well during his administration, but sometimes proved a major problem with later emperors because few were as competent as he had been. Subsequent emperors sometimes behaved as if the laws were truly irrelevant to their own conduct, and the formal relationship between emperor and law was never explicitly defined. Emperors who respected Roman laws and traditions won prestige and veneration for having done so, but there was never a formal legal challenge to imperial authority. Likewise, as the centuries went on and many emperors came to seize power through force, it was painfully apparent that the letter of the law was less important than the personal power of a given emperor in all too many cases.

This extraordinary power did not prompt resistance in large part because the practical reforms Augustus introduced were effective. He transformed the Senate and equestrian class into a real civil service to manage the enormous empire. He eliminated tax farming and replaced it with taxation through salaried officials. He instituted a regular messenger service. His forces even attacked Ethiopia in retaliation for attacks on Egypt and he received ambassadors from India and Scythia (present-day Ukraine). In short, he supervised the consolidation of Roman power after the decades of civil war and struggle that preceded his takeover, and the large majority of Romans and Roman subjects alike were content with the demise of the Republic because of the improved stability Augustus’s reign represented. Only one major failure marred his rule: three legions (perhaps as many as 20,000 soldiers) were destroyed in a gigantic ambush in the forests of Germany in 9 CE, halting any attempt to expand Roman power past the Rhine and Danube rivers. Despite that disaster, after Augustus’s death the senate voted to deify him: like his great-uncle Julius, he was now to be worshipped as a god.

The Imperial Dynasties

Overview

The period of the Pax Romana included three distinct dynasties:

- The Julian dynasty: 14 – 68 CE – those emperors related (by blood or adoption) to Caesar’s line.

- The Flavian dynasty: 69 – 96 CE – a father and his two sons who seized power after a brief civil war.

- The “Five Good Emperors”: 96 – 180 CE – a “dynasty” of emperors who chose their successors, rather than power passing to their family members.

The Julio-Claudian Dynasty

There is a simple and vexing problem with any discussion of the Roman emperors: the sources. While archaeology and the surviving written sources create a reasonably clear basis for understanding the major political events of the Julian dynasty, the biographical details are much more difficult. All of the surviving written accounts about the lives of the Julian emperors were written many decades, in some cases more than a century, after their reign. In turn, the two most important biographers, Tacitus and Suetonius, detested the actions and the character of the Julians, and thus their accounts are rife with scandalous anecdotes that may or may not have any basis in historical truth (Tacitus is universally regarded as the more reliable, although Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars does make for very entertaining reading). Thus, the biographical sketches below are an attempt to summarize what is known for sure, along with some notes on the scandalous assertions that may be at least partly fabricated.

When Augustus died in 14 CE, his stepson Tiberius (r. 14 – 37 CE) became emperor. While it was possible that the Senate might have tried to reassert its power, there was no political will to do so. Only idealistic or embittered senators really dreamed of restoring the Republic, and a coup would have been rejected by the vast majority of Roman citizens. Under the Caesars, after all, the empire had never been more powerful or wealthy. Genuine concessions had been made to the common people, especially soldiers, and the only people who really lost out in the short term were the old elite families of patricians, who no longer had political power independent of the emperor (although they certainly retained their wealth and status).

Tiberius began his rule as a cautious leader who put on a show of only reluctantly following in Augustus’s footsteps as emperor. He was a reasonably competent emperor for over a decade, delegating decisions to the Senate and ensuring that the empire remained secure and financially solvent. In addition, he oversaw a momentous change to the priorities of the Roman state: the Roman Empire no longer embarked on a sustained campaign of expansion as it had done ever since the early decades of the Republic half a millennium earlier. This does not appear to have been a conscious policy choice on the part of Tiberius, but instead a shift in priorities: the Senate was now staffed by land-owning elites who did not predicate their identities on warfare, and Tiberius himself saw little benefit in warring against Persia or invading Germany (he also feared that successful generals might threaten his power, at one point ordering one to call off a war in Germany). The Roman Empire would continue to expand at times in the following centuries, but never to the degree or at the pace that it had under the Republic.

Eventually, Tiberius retreated to a private estate on the island of Capri (off the west coast of Italy). Suetonius’s biography would have it that on Capri, Tiberius indulged his penchant for bloodshed and sexual abuse, which is highly questionable – what is not questionable is that Tiberius became embittered and suspicious, ordering the murders of various would-be claimants to his throne back in Rome, and sometimes ignoring affairs of state. When he died, much to the relief of the Roman populace, great hopes were pinned on his heir.

That heir was Gaius (r. 37 – 41 CE), much better known as “Caligula,” literally meaning “little boots” but which translates best as “bootsie.” As a boy, Caligula moved with his father, a famous and well-liked general related by marriage to the Julians, from army camp to army camp. While he did so he liked to dress up in miniature legionnaire combat boots; hence, he was affectionately dubbed “Bootsie” by the troops (one notable translation of the work of Suetonius by Robert Graves translates Caligula as “Bootikins” instead).

Even if some of the stories of his personal sadism are exaggerated, there is no doubt that Caligula was a disastrous emperor. According to the biographers, Caligula quickly earned a reputation for cruelty and megalomania, enjoying executions (or simple murders) as forms of entertainment and spending vast sums on shows of power. Convinced of his own godhood, Caligula had the heads of statues of the gods removed and replaced with his own head. He liked to appear in public dressed as various gods or goddesses; one of his high priests was his horse, Incitatus, whom he supposedly appointed as a Roman consul. He staged an invasion of northern Gaul of no tactical significance which culminated in a Triumph (military parade, traditionally one of the greatest demonstrations of power and glory of a victorious general) back in Rome.

Much of the scandalous gossip about him, historically, is because he was unquestionably the enemy of the Senate, seeing potential traitors everywhere and inflicting waves of executions against former supporters. He used trials for treason to enrich himself after squandering the treasury on buildings and public games. He also made senators wait on him dressed as slaves, and demanded that he be addressed as “dominus et deus,” meaning “master and god.” He was finally murdered by a group of senators and guardsmen.

The next emperor was Claudius (r. 41 – 54 CE), the one truly competent emperor of the Julian line after Augustus. Claudius had survived palace intrigues because he walked with a limp and spoke with a pronounced stutter; he was widely considered to be a simpleton, whereas he was actually highly intelligent. Once in power Claudius proved himself a competent and refreshingly sane emperor, ending the waves of terror Caligula had unleashed. He went on to oversee the conquest of England, first begun by Julius Caesar decades earlier. He was also a scholar, mastering the Etruscan and Punic languages and writing histories of those two civilizations (the histories are now lost, unfortunately). He restored the imperial treasury, depleted by Tiberius and Caligula, and maintained the Roman borders. He also established a true bureaucracy to manage the vast empire and began the process of formally distinguishing between the personal wealth of the emperor and the official budget of the Roman state.

According to Roman historians, Claudius was eventually betrayed and poisoned by his wife, who sought to have her son from another marriage become emperor. That son was Nero. Nero (r. 54 – 68 CE) was another Julian who acquired a terrible historical reputation; while he was fairly popular during his first few years as emperor, he eventually succumbed to a Caligula-like tendency of having elite Romans (including his domineering mother) killed. In 64 CE, a huge fire nearly destroyed the city, which was largely built out of wood. This led to the legend of Nero “playing his fiddle while Rome burned” – in fact, in the fire’s aftermath Nero had shelters built for the homeless and set about rebuilding the roughly half of the city that had been destroyed, using concrete buildings and grid-based streets. That said, he did use space cleared by the fire to begin the construction of a gigantic new palace in the middle of Rome called the “golden house,” into which he poured state revenues.

Nero’s terrible reputation arose from the fact that he unquestionably hounded and persecuted elite Romans, using a law called the Maiestas that made it illegal to slander the emperor to extract huge amounts of money from senators and equestrians. He also ordered imagined rivals and former advisors to kill themselves, probably out of mere jealousy. Besides Roman elites, his other major target was the early Christian movement, whom he blamed for the fire in Rome and whom he relentlessly persecuted (thousands were killed in the gladiatorial arena, ripped apart by wild animals). Thus, the two groups in the position to write Nero’s history – elite Romans and early Christians – had every reason to hate him. In addition, Nero took great pride in being an actor and musician, two professions that were considered by Roman elites to be akin to prostitution. His artistic indulgences were thus scandalous violations of elite sensibilities. After completely losing the support of both the army and the Senate, Nero committed suicide in 68 CE.

Another note on the sources: what the “bad” emperors of the Julian line (Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero) had in common is that they violated the old traditions of Romanitas, squandering wealth and glorifying themselves in various ways, thus inspiring hostility from many elite Romans. Since it was other elite Romans (albeit many years later) who became their biographers, we in the present cannot help but have a skewed view of their conduct. Historians have rehabilitated much of the rule of Tiberius and (to a lesser extent) Nero in particular, arguing that even if they were at loggerheads with the Senate at various times and probably did unfairly prosecute at least some senators, they did a decent job of running the empire as well.

The Flavian Dynasty