Until the outbreak of the First World War, there had been no essential changes in Ukrainian programs.

By Dr. Vasyl Rasevych

Professor of History

Ivan Franko National University in Lviv

Introduction

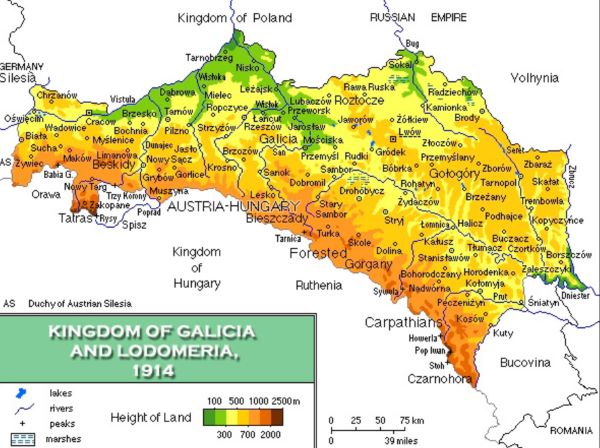

When the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic was proclaimed, on 1 November 1918, on the Ukrainian ethnic territory of the former Austria-Hungary, this did not happen spontaneously or by chance. The creation of the new republic was simply the high point in the development of the Ukrainian national movement in the Habsburg lands. The establishment of a Ukrainian state came as a shock, however, to the Polish elite of Galicia, which had never paid serious attention to the “Ukrainian question.” The newly created state, with its capital in Lviv (Lemberg), where the politically active Ukrainians were in a minority in relation to the Poles, was threatened from the outset by the outbreak of a bloody Polish-Ukrainian conflict that could soon put an end to its existence. The republic lasted only a little more than eight months, but it was the first major step of the Ukrainian movement in its struggle for independent statehood.

The Ukrainian National Movement within the Habsburg Monarchy

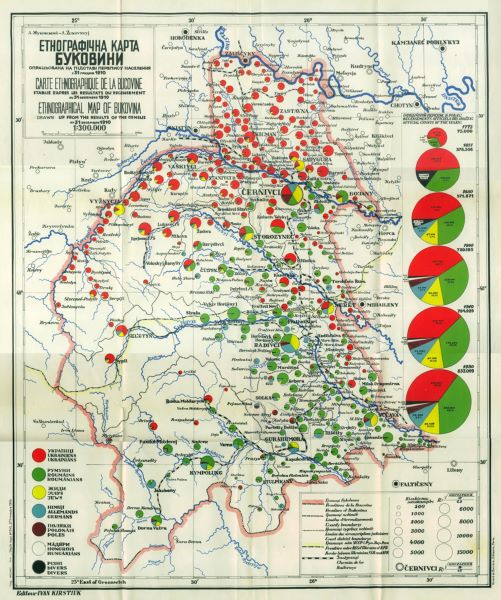

The Ukrainian political movement was in some ways less developed than other national movements in Austria-Hungary. It began only very gradually to address the masses, and the political leadership limited its demands to a partition of Galicia according to ethnic criteria and the unification of Eastern Galicia and Northern Bukovyna to form a separate Ukrainian province within the Habsburg Monarchy. In view of its internal weakness, the Ukrainian movement in Austria-Hungary saw it as one of its priorities to mobilize external support. As a way of dealing with difficulties in relations with Poland, the movement had long oriented itself on the central government in Vienna, and its leadership was traditionally loyal to the Habsburgs.

With the advent of the First World War, the political demands of the Galician Ukrainians became more radical, but this did not affect their program. Before the war, the leadership of the Ukrainian movement had been in the hands of the Ukrainian National Democratic Party (UNDP), distinguished by the fact that its leading bodies consisted mainly of jurists and lawyers. They had grown up in the Austrian legal system, and nothing was further from their minds, even theoretically, than a violent seizure of power, even one that might be formally legitimate. In their ambitions for a state of their own, the Galician political leaders, such as Kost Levytsky, Yevhen Olesnytsky, Yevhen Petrushevych, and even Lonhyn Tsehelsky, remained strictly within the Habsburg paradigm. From being an arbiter in the Polish-Ukrainian conflict, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy would become the source of legitimacy for the new Ukrainian state that was to be created.

Until the outbreak of the First World War, there had been no essential changes in the programs of the most important Ukrainian parties in Galicia and Bukovyna as regards their national and political ideal. The program of the Narodovtsi (1899) stated:

“It is our wish, in an Austrian state that is respected internationally and strengthened by the harmony and satisfaction of all its peoples, to achieve for the Ruthenian people, on the basis of a constitution and by legal means, a political status that is its due among the peoples of this state.”1

This postulate remained later in the program of the UNDP, which described its national political ideal more precisely:

“We, the Galician Ruthenians, part of the Ukrainian-Ruthenian nation that once possessed independent statehood, after which it fought for centuries for its right to political sovereignty, which has never relinquished the rights of an independent nation and does not relinquish them now, declare it to be the final goal of all our strivings to continue working until the whole Ukrainian-Ruthenian people has achieved cultural, economic, and political independence and, in time, is united in a single national organism, in which the whole people can make use of its cultural, economic, and political rights for the general good. In our striving for this goal, and in recognition of our affiliation to the Austrian state, we are working to ensure that the territory occupied by Ruthenians in the Austrian state becomes a province in its own right, with the most far-reaching autonomy in legislation and administration.”2

Until October 1918, the maximal demand of the Ukrainians was for a federalist transformation of the Monarchy and the creation of an autonomous Ukrainian province. As far as the Ukrainian population of Transleithania was concerned, what the Galician Ukrainians wanted, considering that national life there was only in its initial stages, was to establish “close mutual relations” in order “to create a national movement similar to that which already exists in Galicia and Bukovyna.”3 On the nationality question, neither the program of the Ruthenian-Ukrainian Radical Party nor that of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party was particularly radical. What distinguished them from the National Democratic Party were their more progressive social and economic demands and their theoretical plans for agriculture.

On the eve of the war, the leading Ukrainian parties in Galicia and Bukovyna began gradually to move away from their principle of loyalty to the Habsburg Empire, even though this was not reflected in official documents. The discussions over strategy and tactics for building the Ukrainian political movement led to the formation of two competing groups. The dividing line was not between the parties. The polarization grew out of mutual accusations that loyalty to the Austro-Hungarian government was given priority over the concerns of the oppositional Ukrainians. That there was no strategic difference between the aims of both groups is demonstrated by the fact that the “unofficial group,” that is, the opposition, did not create its own structures. Within the then leading political force, the UNDP, the oppositional members did not come together as a group either.

At the head of the official group, which was completely loyal to the Austro-Hungarian government and state, were well-known political figures such as Mykola Vasylko from Bukovyna and Kost Levytsky, the leader of the Galicians. With his aristocratic origins and his study at the Theresian Academy in Vienna, Vasylko was able to establish good contacts with the government and with financial circles in the empire. His political credo rested on two pillars: he stood for a strong Austro-Hungarian state and was unable to imagine life outside the Habsburg Empire.4 In a letter to Wilhelm von Habsburg he defined his political orientation, calling himself a “truly faithful Austrian patriot of the Habsburg dynasty.”5 His unchallenged leadership in the political movement in Bukovyna and his successes in Viennese governing circles even allowed him to control Galician Ukrainian politics for a time. He worked in tandem with Levytsky, both pursuing an ultra-loyal political course.

A group of Galician politicians came together to oppose this orientation. Led by Yevhen Petrushevych, this group included Yevhen Levytsky, Lonhyn Tsehelsky, Volodymyr Bachynsky, and others. The core of the group was made up of representatives in the Cisleithanian Imperial Council (Reichsrat), with the base consisting of the oppositional forces among the Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation (UPR) in Vienna. Having removed the Bukovynian representatives from the UPR, they now had a majority there. The General Ukrainian Council (Zahal’na Ukraïns’kaRada, ZUR) and the People’s Committee (Narodnyi Komitet), the leading organ of the Ukrainian National Democratic Party, remained in the hands of Kost Levytsky’s supporters. As conflict developed between these two currents, the opponents of the loyalist course not only did not produce new slogans but also did not question the methods of political struggle. They shared the idea of autonomy and regarded petitioning as their principal political activity.

The first hard blow to the pro-Austrian loyalist position was the Two Emperors’ Manifesto of Kaiser Franz Joseph I and Kaiser Wilhelm II in November 1916. It announced the intention of Austria-Hungary and Germany to establish a Polish kingdom in the foreseeable future on territory wrested from Russia. The Polish factor was much more important to the Habsburg Empire than the young and confused Ukrainian movement. The Habsburgs depended on Polish support. Vienna did not intend incorporating Galicia into the Kingdom of Poland, but regional autonomy would be further extended.6 Among the Ukrainian population of the empire, the manifesto provoked a storm of outrage that continued even after the death of the emperor. The Ukrainians of Galicia protested, and the new emperor, Karl I, promised to take account of Ukrainian demands, but only after the war. Ukrainian political circles in Galicia considered the very fact that such a manifesto could appear to be a declaration of bankruptcy for the loyalist policies of the group around Levytsky and Vasylko.

The politicians who had opposed this course forced the previous leadership to resign, and Vasylko was also forced to resign as vice president of the General Ukrainian Council, thereby losing the right to speak in the name of the whole Ukrainian movement in Austria-Hungary. This shift in the balance of forces had a negative effect on Ukrainian politics generally. Shortly before the publication of the manifesto, Vasylko had attempted to establish contact with influential government circles in Germany. He was able to have a number of talks with the German side that gave him clearly to understand that their position on the future of Galicia and the whole of Ukraine differed on a number of points from that of their Austro-Hungarian allies. In a letter of 25 November 1916, Vasylko summarized the German position on the Ukrainian question as follows:

“Of course, all measures here are dictated first and foremost by German interests. On the other hand, it is a fact that the Germans are absolutely clear that our interests are also exceptionally important and decisive for them. In this respect, they really want to support us and offer serious assistance. There is therefore no basis for the exaggerated pessimism that is widespread among uninformed circles with regard to Germany, just as there was also no basis for the previous exaggerated hopes.”7

Even Vasylko’s main opponents, the group around Petrushevych, had to admit that after his departure from the Ukrainian stage Germany’s interest in the “Ukrainian card” began to wane.8 Having lost any influence over Galician politics, Vasylko concentrated on leading the Ukrainian clubs of Bukovyna, where he pursued his previous line. The split in the Ukrainian movement between the Galician and Bukovynian politicians certainly did not contribute to a positive image abroad, especially in the central government in Vienna.

When parliament resumed in 1917, the demands from representatives of the various national groups concerning national autonomy had become much more radical. The Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation declared that the continuing subordination of the Ukrainians to the Poles, in a single province, was nothing but disregard for national rights and for the principle of national self-determination. Under the leadership of Yevhen Petrushevych, the UPR categorically rejected any form of community of Ukrainians and Poles in one and the same province.9 The partition of Galicia was now a minimal demand. Vienna answered with delaying tactics.

An analysis of all the documents and the press (including the oppositional ones) leads one to the conviction that in 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Ukrainians saw themselves pressured by circumstances into choosing between an all-embracing Ukraine and loyalty to the empire. Most were inclined to support autonomy within a reformed Habsburg Monarchy. There were many reasons for this. When the war began, the Ukrainians had decided unequivocally to fight on the side of the Central Powers.10 This had to do with the weakness of the Ukrainian movement and with the fact that Russia was part of the Entente. The Austro-Hungarian orientation was the firm foundation of the policy of the Ukrainian parties. In the preface to his book Zoloti vorota,11 in which he assessed Ukrainian politics at the time, Vasyl Kuchabsky explained its source: “In view of the weakness of the Ukrainian people, the afflictions imposed by the occupying states, Austria and Russia, were absolutely unwelcome, but they were the least unwelcome. One of the essential tasks of Ukrainian policy, then, was to convince these powers that the increasing national consciousness and culture of the Ukrainian people would not lead to a derogation of its loyalty. The tactic of loyalism, on which, in Ukraine’s national interest, no shadow should fall, became an axiom of Ukrainian political thought.”12

This policy of loyalty to Austria-Hungary on the part of the Ukrainians within the empire did not prevent them, however, from forging radical plans for territory wrested from the Russian Empire. At the start of the First World War, a political organization of Ukrainians from Russia was formed in Lviv, the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (Soiuz vyzvolennia Ukraïny, SVU). The SVU was a nonparty organization that represented the political interests of Ukrainians under Russian rule. Its political plans were linked to a defeat of Russia in the war and the overthrow of tsarism so that, “out of its ruins,” a “free and independent Ukraine” could emerge.13 The SVU received considerable financial support from the Austro-Hungarian government on condition that it be used solely for propaganda in the Russian Empire.14 Galician politicians were deeply involved in this, and there is no doubt that some SVU material was distributed in Bukovyna and Galicia. With the formation of the SVU, a “legal” basis existed for the development of a concrete program for a future independent Ukrainian state. The Galicians eagerly began developing concrete plans for Ukrainian territory in Russia.15 Kost Levytsky continued to insist throughout 1917 that the main task of the Ukrainian political movement was “the liberation of Ukrainian territory from foreign rule and the creation of state constitutional organs of self-determination for the Ukrainian people.”16 The implementation of this demand was, for him, unequivocally bound up with Austria-Hungary. It was his view that this initiative would allow the Galician Ukrainians to maintain “clear and unambiguous” relations with Austria.17 This was also the position of the oppositional Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation, which adopted the following resolution in February 1917:

“The Ukrainians wish for nothing other than a close affiliation with Austria; not one, however, that is dependent on other constitutionally equal factors, but one that affiliates us directly with the Empire.”18

Possible unification in an all-embracing Ukraine was mentioned only when the task was to wrest political concessions from the government in office, such as the founding of a Ukrainian university or the partition of Galicia. This tactic was explained by Levytsky in 1919. In 1918 the Ukrainian National Democrats had formulated very clear demands on the central government in Vienna:

“either the Ukrainian territory within the Austrian Monarchy obtains the independent constitutional order under Austria that is its due, with an end to Polish sovereignty, or, regardless of how much Austria might not want this or be able to accomplish it, our road will lead not to Warsaw but to Kyiv, to unite us with the Ukrainian state whose independence has been proclaimed by the Central Rada in Kyiv.”19

Cautious Preparations for Autonomous Statehood in 1918

The radicalization of other national movements in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918 prompted the Ukrainians to make preparations for a possible collapse of the empire. From September–October, Ukrainian politicians began to play a double game in that they worked out the modalities for a federalist transformation of the empire while, at the same time, preparing the foundations for an independent state. Lonhyn Tsehelsky, a deputy in the Cisleithanian Imperial Council and one of the best-known representatives of the opposition, described this period in his memoirs:

“We were outwardly loyal to Austria but were preparing its overthrow. If Austria managed to survive, we would be part of its federal structure. In the event of its disintegration, we were determined and prepared to proclaim our own independent state and, should the occasion arise, to unite with greater Ukraine.”20

Hopes for possible reform of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy were strengthened, to some extent, by the events connected with the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty, for it was here that the Central Powers not only recognized the existence of a sovereign Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) in Kyiv but also, in a secret appendix to the treaty, guaranteed the establishment of Ukrainian national political autonomy within the Habsburg Monarchy (the Crownland Protocol). There had also been agreement on a border favorable to the Ukrainians in the Kholm region. On this occasion, the People’s Committee of the UNDP met in extraordinary session. The resolution passed by the People’s Committee greeted the recognition of the fact that the Ukrainian state existed and proclaimed that “the whole Ukrainian people of Galicia will exercise its right to statehood within the borders of the Habsburg Monarchy.”21 At an extraordinary session of the People’s Committee on 18 February 1918, it was resolved that in all the districts of Galicia a festival would be held on 3 March under the slogan, “Long live Ukrainian statehood in the Habsburg Monarchy.”

The Polish population of Eastern Galicia responded to the Brest-Litovsk treaty, especially to the losses in the Kholm region, with strikes and protests aimed at preventing Austria-Hungary from implementing these undertakings. And although the Ukrainian parties succeeded in mobilizing a mass movement such as had never been seen before in support of the undertakings given in Brest-Litovsk, the Austro-Hungarian government never risked implementing the secret Crownland Protocol.22

Another blow to the positions of the committed Austro-Hungarian autonomists was the coup in Kyiv. German troops supported Hetman Skoropadsky’s seizure of power and recognized his Ukrainian State. This severely restricted the Austro-Hungarian Ukrainians’ freedom of action, as threats to unite with Kyiv in a single Ukrainian state were no longer effective. Kost Levytsky considered three ways out of this situation:

“First, an understanding with the Hetman, since he nourishes good intentions with regard to an independent Ukrainian state; second, an alliance with Ukrainian parties to fight the Hetman for the democratization of the Ukrainian State; or, third, support for the Austro-German movement in Ukraine.”23

A resolution was passed at a meeting of the People’s Committee on 11 May 1918 that clearly condemned Germany’s “brutal interference” in the internal affairs of Ukraine.24 The UNDP also recognized the right of the political organization that had created the Ukrainian People’s Republic, the Central Rada, to continue to exercise state power. The committee also declared that “the Central Powers, which demand that the UNR adhere to the Brest-Litovsk treaty and its additional provisions, are also themselves legally and morally obliged to fulfill those undertakings into which they entered with the UNR and with the whole Ukrainian people in the Brest-Litovsk treaty and its additional provisions, whether publicly or confidentially.” This meant that the Central Powers should hand over Kholm and Pidliashia (present-day Podlachia) to the UNR. The strong condemnation of Germany for its brutal interference in Ukraine’s internal affairs did not cause the Galicians to change their position with regard to the Austrian government. They wanted it “to partition Galicia, in keeping with its commitments, and to establish a separate state organism in Eastern Galicia and Bukovyna within the framework of Austria.”25

In the summer of 1918 Yevhen Petrushevych, head of the Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation in the Austrian parliament, said that “the star of the Habsburg dynasty still shines bright and clear in our firmament.”26 By the autumn of 1918, however, there were few politicians who did not see that what was coming was a victory of the Entente and the inevitable collapse of Austria-Hungary. From this time on, secret groupings emerged throughout the empire that worked on different models for the future restructuring of the state. With the announcement of President Woodrow Wilson’s “fourteen points,” at the latest, the principle of self-determination of nations had become a fundamental postulate of international politics. Wilson’s program promised independence for Poland. For the peoples of Austria-Hungary, he promised “the freest opportunity for autonomous development.” The Ukrainians took this declaration very seriously. It prompted the Galicians to pursue their struggle for independence even more vigorously.27 Educated in the spirit of Austro-Hungarian constitutionalism, they continued to rely on international resolutions and “thereby underestimated the potential of their own people.”28

The Ukrainian politicians of Galicia found it very difficult to depart from their basic principle of the unconditional legitimacy of power, which is why, even as they developed their own plans, they always did so with reference to Austria. Even when Emperor Karl rejected the Ukrainian demand for the partition of Galicia, and it became clear that Ukrainian autonomy was not to be part of the planned transformation of the Monarchy, the Galician Ukrainians still hoped for a legislated solution. It was for this reason that they did not proclaim the unity of all Ukrainian territories in Austria-Hungary until after Karl’s manifesto of 16 October 1918 announcing the transformation of Austria into a federal state.29 But even then, the group around Kost Levytsky did not go beyond demanding agrarian reform, which they saw as an extremely radical step, equivalent to an attack on Austro-Hungarian power: “At that time (autumn 1918), it was clear to us that the collapse had to come. It was suggested in the People’s Committee that our response to this should be a demand for agrarian reform, since our program called for land, especially the large estates, to become the property of the people, without compensation, and for this land to be distributed to the peasants with little or no land.”30 The fact that the Ukrainians made this demand at a time when the other peoples of the empire, no longer satisfied with federalism, were declaring their own independent states, demonstrates their “backwardness” and their late entry into this process. What is more, the Ukrainian political leaders tried for a long time to ignore the fact that the Entente had given up any plans for a separate peace with Austria-Hungary, which meant, in practice, that the disintegration of the empire into nation-states was inevitable. It was not until the autumn of 1918 that the leadership of the People’s Committee adopted a new slogan and began to prepare for the collapse. Stepan Baran later recalled this historic decision:

“There was only one thing left for us to do: to make ourselves ready, at the last minute, to ensure that the Ukrainian lands in Austria-Hungary did not come under a foreign yoke. Therefore, when I returned from the country at the beginning of September, at the first session of the People’s Committee on 7 September 1918, which had been put off until then by the leaders of political life in our region, as secretary of the committee I took a decisive step by pointing out the need for our forces to prepare for the moment of Austria-Hungary’s collapse and, when necessary, to establish our own state organism.”31

At this highly conspiratorial session, it was decided to establish a coordinating body to prepare for the collapse of the empire. Two commissions of the People’s Committee were created:

“An organizational commission to instruct the organs with a view to taking over administration in Eastern Galicia and a military commission to prepare the armed forces to carry out a coup.”32

The members of the organizational commission were Volodymyr Okhrymovych, Vasyl Paneiko, and Stepan Baran. Since its activity was “strictly conspiratorial,”33 the committee left no documents behind. The decisions of the People’s Committee were only reported verbally. Levytsky was the liaison to the Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation, and his task was to inform the UPR about the decisions of the People’s Committee. Some members of the UPR had their own plans for the overthrow of the empire. This alternative group was led by Yosyf Folys, Ivan Kyveliuk, and Lonhyn Tsehelsky. Originally they had tended to support the idea of a “transformation of Austria-Hungary on a federal basis,”34 and their ultimate aim was to persuade the Austro-Hungarian emperor “to carry out a coup from above, in other words, to dissolve or suspend parliament and introduce a new constitution by imperial edict that would create autonomous regional national states united in a federal state, with a federal parliament responsible for foreign and military affairs.”35 To realize this plan, Folys and Tsehelsky made contact with representatives of the Slovenian, Croatian, and Czech national movements. At a joint meeting in the autumn of 1918, they decided to propose to Emperor Karl “that, before the coup, military commanders and units in the national capitals be replaced by those that would be subordinate to the national constituent assemblies and would prevent any unrest directed against the coup.”36 Galician politicians and religious dignitaries, among them Yuliian Romanchuk, Yevhen Levytsky, Volodymyr Bachynsky, Yevhen Petrushevych, Tyt Voinarovsky, Stepan Smal-Stotsky, Sydir Holubovych, Ivan Kyveliuk, Oleksander Stefanovych, Andrei Sheptytsky, Vasyl Paneiko, Volodymyr Okhrymovych, and Teodosii Lezhohubsky, were informed of these intentions.37

The Cossack officer Petro Bubela, assisted by two other officers, Volodymyr Ohonovsky and Dmytro Paliiv, was chosen to make the necessary preparations and carry out agitation among Ukrainians in the Austro-Hungarian army.38 Tsehelsky wrote in his memoirs:

“The coup had already been decided secretly by the leaders of the Ukrainian National Council in August 1918 as it became clear that Austria could not escape catastrophe. The organizer of the coup was to be a liutenant in the Austrian army, Petro Bubela, a determined, quiet, even-tempered, and discreet man.”

The plan was thwarted to some extent by the sudden death of Folys. Nonetheless, the “trio for carrying out the military coup” performed its main task in that it not only designed the scenario for the transfer of power but also identified the pro-Ukrainian forces inside the imperial army and consolidated them in a system of secret organizations. The trio was led politically by a commission established by the Ukrainian National Council and consisting of Kyveliuk, Tsehelsky, and Paneiko.39 According to Tsehelsky, this commission, which was also secret, was already in a position on 25 October 1918 “to inform the delegates of the Ukrainian National Council in Lviv and the delegates in Vienna generally about preparations for the coup on the territory between the Zbruch and the San.”40

But the implementation of the UNDP People’s Committee’s plan was an entirely different matter. According to Stepan Baran, the People’s Committee had set up its own commission to carry out the coup, and it actually made preparations. Baran wrote in 1923 that it was his initiative to establish the military committee:

“Knowing that a military organization would be necessary in order to perform our task, we decided at the second meeting to seek out reliable people among the Ukrainian officers in Lviv and set up our own military committee with the task of carrying out the military organization. I turned to Cossack officers known to me, Liubomyr Ohonovsky, Vasyl Baranyk, and Ivan Vatran. We enlarged the commission by bringing in Dr. Stepan Tomashivsky, Dr. Mykhailo Lozynsky, and Omelian Saievych.”41

The officers called upon to join the commission were in agreement with the creation of their own Ukrainian military committee. There is reason to believe that this committee played a decisive role in the events of 1 November 1918. Its membership and essential tasks were later confirmed by one of the participants in those events. Vasyl Paneiko wrote that, having returned from Switzerland, he was active in the organization of a secret committee that included Okhrymovych, Stepan Rudnytsky, Mykhailo Lozynsky, Stepan Tomashivsky, and Osyp Nazaruk.42 The meetings of the committee, which was in touch with the military committee, were held in the museum of the Shevchenko Scientific Society.43

On behalf of the committee, Vasyl Paneiko traveled to Bukovyna to make contact with the Ukrainian Legion in order to expedite its move to Lviv and choose the commander of the uprising. He was uncertain about the extent to which the commander of the Legion, Archduke Wilhelm von Habsburg, was committed to the Ukrainian cause and, with the help of Ostap Lutsky, selected Dmytro Vitovsky for that role.44 In the end, however, he was not happy with this choice, and so, in the military committee, he insisted on naming another organizer for the uprising. He was allowed to travel to Kyiv “in order for the Hetman to select a commander.”45 The Galician politicians had thought of Oleksandr Udovychenko, but the Hetman did not agree.

Stepan Baran invited the Ukrainian otamans Teodor Rozhankovsky and Nykyfor Hirniak to Lviv for consultations. It was then decided that the Ukrainian Legion should organize the military coup. Representatives of the Legion reached agreement on their plans with the military committee and began to prepare the uprising.46 Knowing that the other Ukrainian parties did not have such a dense network in the regions, Baran decided to consolidate forces for the preparation of the uprising that was to take place on 1 November and invited the best-known politicians from the districts, regardless of party affiliation, to a meeting. His main demand to the political activists was that they establish district committees to assume the functions of state administration at the given time.47

It was decided that the general political direction of the state-building process should be entrusted to an assembly designated as the “Ukrainian National Council.”48 This decision was taken on 10 October 1918 at a session of the UPR at which Petrushevych, Romanchuk, Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, and other prominent Ukrainian representatives were present. Yevhen Levytsky was given the task of producing the statute for the Ukrainian National Council, and Bachynsky was made responsible for the convocation of the constituent assembly.49

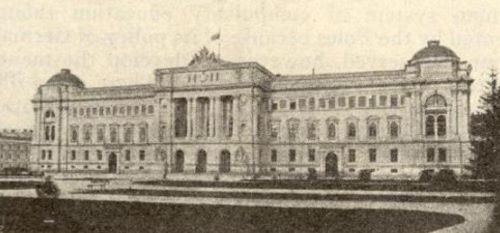

On 18 and 19 October 1918, an assembly was held in Lviv with public officials and representatives of the various political parties. Those attending included the Ukrainian representatives in the Vienna parliament and in the Galician Diet, along with representatives of the Greek Catholic Church. On the basis of Emperor Karl’s manifesto, the assembly declared itself to be the Ukrainian National Council with parliamentary authority. At the head of the Council was a representative to the Vienna parliament, Yevhen Petrushevych. In accordance with the principle of national self-determination, the Council proclaimed the formation of a Ukrainian state on Ukrainian ethnic territories in Austria-Hungary. Although not all the territories claimed were represented at the assembly, the National Council declared that the new state included not only Eastern Galicia and Northern Bukovyna but also Transcarpathia (which had no representatives at the assembly).50 The relation of the newly proclaimed state to Austria-Hungary remained undefined. That would depend on the decisions taken by the Entente with regard to the future of the Monarchy.51 In the event that the Entente decided to dissolve the Monarchy, the Ukrainian National Council reserved for itself the right to form a union of Ukrainian territories in Austria-Hungary with Ukrainian territory previously part of the Russian Empire.

The resolutions announced by Petrushevych to the assembly of 19 October 1918 did not satisfy the representatives of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party. Some of the Radicals and National Democrats were also opposed. The problem was the absence of any clause providing for the unification of Ukrainian territory in Austria-Hungary with the Ukrainian State.52 On the following day, Petrushevych headed a delegation to Vienna for further negotiations with the Austro-Hungarian emperor. Some of the participants in the Lviv assembly hoped for the proclamation of an independent Ukrainian state and demanded a complete break with Vienna. The political leaders of the Ukrainian movement in the Habsburg Monarchy based their position on the claim that their forces were too weak to be able to declare the unity of all territories in an all-embracing Ukraine. The Ukrainians in Cisleithania were not such a significant revolutionary force that they could separate their territory from Austria-Hungary, confront Poland’s ambitions for power in the region, and implement a unification with the Ukrainian People’s Republic, which had existed since the beginning of 1918.

But it was not just the relative weakness of the Ukrainian movement in Austria-Hungary that led to this moderate decision. When they thought about an all-inclusive Ukraine, the Austrian Ukrainians knew they could not count on political agreement with the Ukrainian State of Hetman Skoropadsky. There had been poor relations right from the start between the Ukrainian State and Austro-Hungarian politicians. The Hetman was mistrustful of Germany’s Austro-Hungarian ally. The plans of the Galician politicians and the Habsburg Monarchy regarding the future of the Ukrainian political order worried him. He championed a plan for a “Greater Ukraine” that would include not only all ethnic Ukrainian territories but also the Crimea and the Kuban. The Austro-Hungarians favored a “Little Russian” solution, with Eastern Galicia and Northern Bukovyna remaining outside, or a unification of all Ukrainian territory with the Habsburg Crown. Skoropadsky was especially disturbed by the “Greek Catholic” plan for the postwar period. According to that plan, the Habsburg Archduke Wilhelm, whose Ukrainian name was Vasyl Vyshyvany, would mount the Ukrainian throne and unite all Ukrainian territory in a personal union with the Habsburg Crown. Galician Ukrainian support for that plan was the cause of the intra-Ukrainian conflict. But what most divided the Ukrainians on both sides of the border were their conceptions of Ukrainian statehood, the nation, and the Greek Catholic Church.53

The activities of Archduke Wilhelm not only provoked Hetman Skoropadsky’s resistance but also created confusion in the plans of the Galician politicians. Not all of them shared the idea of a monarchist future under the house of Habsburg. Most of them did not know what the archduke’s plans were. Unlike the majority of the Galician Ukrainian politicians, however, Wilhelm had had a good deal of personal experience of the Hetman. In a letter of 18 October 1918 to Metropolitan Sheptytsky, he warned against a union of Galicia and Bukovyna with the Ukrainian State.54 In this letter he described Skoropadsky as a “colossus with feet of clay” that could come crashing down at any moment and bury with it any hope of Ukrainian independence. In his view, the optimal form of statehood would be national autonomy within the borders of the Habsburg state. In the same letter, he expressed his agreement with the strategy and plans of the group around Kost Levytsky.

That Ukrainian politicians, as late as October 1918, did not want a complete break with Austria-Hungary is demonstrated by the fact that, at the session of the Ukrainian National Council on 19 October that decided on the composition of delegations, the Council chose not only a Galician delegation under Kost Levytsky and a Bukovynian delegation under Omelian Popovych but also an executive delegation in Vienna.55 The National Council found it extremely difficult to make a complete break with Vienna. Its presidium continued to negotiate with the Austro-Hungarian government as if it were not aware of the catastrophic situation in Vienna. On 23 October, when the Ukrainian delegation informed the Austrian prime minister, Max Hussarek von Heinlein, about the decision of the Ukrainian National Council in Lviv, they assured him that the new state would maintain close links with the empire. They wanted the prime minister to appoint Levytsky governor of Galicia so that he could introduce reforms that would give the Ukrainians predominance over the Poles.56 What is also remarkable is the fact that, not just in October but even after the proclamation of the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic, a significant number of Ukrainian politicians remained in Vienna, even the president of Western Ukraine, Yevhen Petrushevych.

The Race against the Poles

The Ukrainians were forced to act quickly by news of the planned arrival of the Polish Liquidation Commission, formed in Cracow on 28 October 1918, which was to take over power in the region. Lviv was to come under Polish rule on 2–3 November. The decisive action of the Poles made it necessary for the Ukrainians to be more determined.57 The Lviv delegation began concrete preparations on 25 October. Under the leadership of Roman Perfetsky, an organizational bureau was created that issued instructions at district and local levels for the establishment of Ukrainian rule. On 31 October, the People’s Committee of the UNDP entrusted all preparations to the delegation of the Ukrainian National Council in Lviv.58

Polish preparations for the proclamation of an independent state, unlike those of the Ukrainians, were more systematic and better organized. No one had any doubts as far as a future renewal of Poland was concerned. As early as 15 September 1917, the Regency Council of the Kingdom of Poland was established, with the agreement of Germany and Austria-Hungary. This was the first and most important step toward the creation of a Polish state administration for all Polish territories. On 7 October 1918 the Regency Council proclaimed the independence of Poland and, on the next day, took over command of troops from the occupying Central Powers. As the supreme organ of the Polish state, the Regency Council declared that it was necessary to establish both economic and political independence, guaranteed by international treaty, as well as territorial integrity.59 The goal of Poland’s political leadership was the unification of all of Poland’s “historical” territory, and it regarded the problem of Galicia as an “internal Polish affair.” This made the outbreak of Polish-Ukrainian conflict practically unavoidable.60

In all their preparations for the founding of new states, both Poland and Ukraine continued to look to Vienna, still the capital of the empire. The Liquidation Commission under Wincenty Witos, established in Cracow on 28 October, proclaimed the takeover of power in all of Galicia and informed the Austrian prime minister, Heinrich Lammasch, and the Galician governor, Karl von Huyn. The Poles, considering the transfer of power from the Austrian governor to the Polish side legitimate and justified, planned a journey of their representatives to Lviv, where this act was to take place. The Ukrainian National Council also proclaimed its authority over the territory. Neither the Poles nor the Ukrainians paid any attention to what the other side was doing, but both wanted a legitimate transfer of power from the Galician governor. The Ukrainian delegation in Vienna had apparently succeeded in getting recognition from the Austrian Council of Ministers of the right of the Ukrainians to their own state, but that decision never reached Lviv. Therefore the Galician governor, von Huyn, did not have the formal authority to relinquish power and transfer it to the Ukrainians. In response to the demands of the Ukrainian delegation, he declared on 31 October that he would not transfer power to either the Ukrainians or the Poles, since the problem would have to be resolved by a peace conference.61 But there is no agreement about this fact. Some politicians declared that Prime Minister Lammasch, in response to the demands of the Vienna delegation of the Ukrainian National Council, had instructed the Galician governor to hand over power to the Ukrainian representatives, but that the telegram with this instruction had been intercepted by the Poles in Cracow.62

During the night of 31 October/1 November the Ukrainian military command, led by an officer of the Ukrainian Legion, Dmytro Vitovsky, carried out the uprising, seized power in the Galician capital, and later took administrative control of more than fifty districts. In its appeal to the “Ukrainian people,” the Ukrainian National Council announced the establishment of a Ukrainian state:

“The Ukrainian state and its supreme organ, the Ukrainian National Council, were established according to your will on 19 October in the Ukrainian lands of the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The Ukrainian National Council has this day taken power in the capital, Lviv, and on the whole territory of the Ukrainian state.”63

Western Ukraine’s Struggle for Survival

The Ukrainian National Council announced that until political power was properly reorganized, the local Ukrainian district and village organizations would continue to carry out their usual functions. All soldiers of Ukrainian nationality were mobilized to defend the young state. A special summons was issued to Ukrainian soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army outside Galicia. They were to return as rapidly as possible to their new state and serve in its defense. Until a new Ukrainian army was created, the maintenance of public order and defense would be carried out by so-called military units, which would include members of the general public capable of bearing arms.

Everyone living on its territory, regardless of nationality or religion, would be a citizen of the new Ukrainian state. National minorities (Poles, Jews, Germans) were guaranteed equal rights and would elect their own representatives to the Ukrainian National Council. All former laws would remain in force on the territory of the Ukrainian state except those that contradicted the principles of the new state. Once the new state structure had been consolidated, a constitutional assembly would be elected on the basis of direct and universal franchise. Jurists would be charged with getting to work immediately on drafting a constitution.

The seizure of power in Lviv was peaceful, and the leadership of the National Council rejected the suggestion that three hundred leading representatives of the Polish population should be arrested as security in case of Polish resistance. The new Ukrainian government did not want to provoke any violence on the part of the Poles. Nevertheless, on 1 November, the Poles began to mobilize their forces for battle against the Ukrainians. In Lviv, a Polish National Committee was established under the leadership of Tadeusz Cieński. The military leader of Polish forces was Czesław Mączyński.64 The battle began for the key parts of the city.65 Unfortunately for the Ukrainians, the Ukrainian Legion did not arrive on time from Chernivtsi. The Legion was supposed to defend the city while the rest of the Ukrainian military forces were being organized. The fact that the Legion did not arrive until three days later had a negative effect on the defensive capacity of the Ukrainian forces. The first military units that fought against the Poles and later joined the Legion were the basis on which the Ukrainian Galician Army would be built, the army of Western Ukraine.

The fighting between the Poles and Ukrainians in Lviv lasted from the very first day on which the Western Ukrainian state was proclaimed until 21 November. The leadership of the new state was then forced to leave the city along with its troops. In this short time, however, the Ukrainians managed to establish the most important state agencies. On 9 November 1918 the National Council established its provisional executive organ, the State Secretariat of the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic, which then functioned as government from 13 November.66 On the same day, the constitutional foundation of the new state was established, the “Provisional Basic Law on the Sovereign Independence of the Ukrainian Lands of the Former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy,” and the official name of the new state was the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic (Zakhidnoukraïns’ka Narodna Respublika, ZUNR). In a very short time, the ZUNR had been able to develop the essential juridical foundation to regulate the most important areas of public life: organization of the military, the provisional organization of legal jurisdiction, official language, the educational system, citizenship, and land reform. An analysis of the documents shows that the basic principles underlying ZUNR law were democratic and, to some extent, liberal. The state that claimed, even if only declaratively, 70,000 square kilometers and 6 million people did not intend to become monoethnic.67 The ZUNR guaranteed its national minorities freedom of development and proportional representation in the supreme legislative body, even if, in practice, the national minorities refused to send representatives to the Ukrainian National Council and it remained in reality an exclusively Ukrainian body.68

On 25 October 1918, simultaneously with the events in Galicia, the Ukrainian Regional Committee of Bukovyna was established in Chernivtsi under the leadership of Omelian Popovych as the Bukovynian central administration. The committee lacked both a widespread network in the province and support in the city. Two days later, Romanian representatives in the Vienna parliament established the Romanian National Council, which began immediately to secure its power in Bukovyna. On 3 November, the Ukrainians held a mass assembly in Chernivtsi that declared Bukovyna part of a united Ukrainian state. Popovych became president of the province. In view of the internal weakness of the Ukrainian movement in Bukovyna, and based on its experience with Austria-Hungary’s constitutional management of inter-ethnic problems in the Habsburg Monarchy, the Ukrainian Regional Committee began negotiations with moderate Romanian representatives. They were able to reach agreement with only one of the Romanians, Aurel Onciul, who had limited influence on the situation. On 6 November, the provincial administration of Bukovyna handed power to Popovych and Onciul, who proceeded to act on behalf of both the Ukrainian and Romanian national organizations. These institutions would govern the respective parts of the province in which their ethnic group was in the majority. The Romanian National Council, however, led by Jancu Flondor, had no intention of sharing power with the Ukrainians. The council’s leaders immediately asked Romania to send troops.69 The Romanian army did not hesitate and, on 11 November, occupied the whole of Bukovyna, including Chernivtsi. Although Bukovyna was only nominally part of the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic, it was military intervention from outside that brought down its legitimate government.70

There were no representatives of Transcarpathia at the meeting of the Ukrainian National Council on 19 October. The separatist process began here much later than in Galicia and Bukovyna, and under very different circumstances. The new Hungarian Republic under Mihály Károlyi laid claim to all territories that had been under the jurisdiction of the Hungarian Kingdom.71 Among the Transcarpathian regions, the most strongly pro-Ukrainian were Máramarossziget (present-day Sighetu Marmaţiei) and the area around the city of Huszt (present-day Khust). However, the fact remains that, apart from a brief presence of Ukrainian troops, Transcarpathia was never under ZUNR control.

The State Secretariat and the National Council left Lviv on 21 November and moved to Ternopil. The loss of the capital had a negative effect on the fighting morale of the Ukrainian Galician Army. When the Poles finally captured Lviv, they not only closed Ukrainian institutions and carried out searches and arrests but also instigated a bloody pogrom against the Jewish population of the city. It has been argued that this pogrom was an act of revenge for Jewish neutrality toward the Ukrainian state, but in reality it was a typical bloody anti-Semitic action that involved robbery, murder, and rape. It is estimated that 78 people were killed and 453 wounded in this pogrom. Altogether 13,375 people had their belongings plundered or lost their homes.72 Ukrainians, too, were not spared by the new authorities. Those regarded as the greatest security risks were sent to an internment camp in Dąbie, while the rest, including priests, were imprisoned in Lviv.

The Ukrainian government remained in Ternopil until 2 January 1919, when it moved to Stanyslaviv (present-day Ivano-Frankivsk). A meeting of the Ukrainian National Council was held here on 3 January and declared its intention to unite with the Ukrainian People’s Republic “in an undivided sovereign republic.”73 The act of union, which took place on 22 January 1919 in St. Sophia Square in Kyiv, was purely symbolic. Following the union with the UNR, the official name of the ZUNR was Western Province of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The two governing bodies, however, continued to operate separately. In spite of the union and the military assistance and food supplies that the Galicians obtained from the UNR, the leadership in the Western Province continued to follow its own line in both domestic policy and international relations.

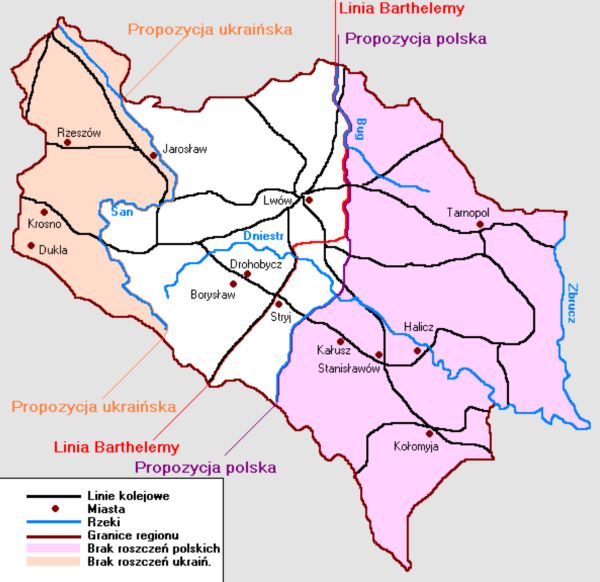

The war between Western Ukraine and Poland continued with mixed results.74 On two occasions, the Ukrainians almost reached Lviv but never succeeded in capturing it. Attempts on the part of the Entente to mediate failed a number of times. Symon Petliura, the head of the Directory in Kyiv, visited Western Ukraine once but was really on the side of the Entente. He tried to get the Western Ukrainians to compromise, hoping that they would then be able to redirect their army from fighting the Poles to fighting the Bolsheviks. For the Galician Ukrainians, however, the Poles were the main enemy. They could not let the Poles take their territory, to say nothing of making an agreement that would amount to a capitulation.75 All attempts by the Entente to end the Polish-Ukrainian conflict would have been at the expense of the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic, which is why they all failed. The final warning to the Western Ukrainians was the threat from the mission led by Joseph Berthélemy on 28 February 1919 that if the ZUNR rejected the Entente’s conditions, it would face the army of General Józef Haller, a Polish army created in France. It was well armed and would pose a serious threat to the weakened Ukrainian Galician army. Under cover of the fight against the Bolsheviks, it was moved to Eastern Europe to fight the ZUNR.

By June 1919, after exhausting battles, the Petrushevych government controlled only a tiny amount of territory, consisting of parts of the Borshchiv, Husiatyn, Chortkiv, and Horodenka districts. On 9 June, faced with the threat of defeat, Petrushevych abolished the office of president and the State Secretariat and proclaimed himself dictator. The government and the State Secretariat were replaced by the plenipotentiaries of the Dictator and the Military Chancellery. He removed the military command, which led to some short-term successes. On 25 June, however, Poland received official permission from Paris to extend its military operations over the whole territory as far as the Zbruch, which amounted to approval from the Entente for the occupation of Galicia.76 Approval for the deployment of the Haller army on the Galician front came at the same time. Polish troops reached the Zbruch on 17 June and forced the Western Ukrainian government out of Galicia.

The brevity of the existence of the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic had to do with a number of factors. Among the internal factors were the asymmetrical structure of Ukrainian society (the complete absence of a nobility and a stratum of major industrialists), the lack of competent officials (a small number of Ukrainians in the Austrian civil service), the shortage of experienced military commanders, and weak support for the Ukrainian demand for independence among the urban population. There was no Ukrainian majority in almost all the larger and smaller towns in Galicia; furthermore, neither their economic nor social status enabled them to have significant influence on the socioeconomic and political conditions in the towns. Among the external factors were the international community’s lack of familiarity with the Ukrainian question and the unfavorable international circumstances.

Endnotes

- TsDIA Lviv, f. 146, op. 7, spr. 4529, 12, Narodna prohrama. Nakladom Tovarystva “Narodna Rada,” pid zariadom K. Bednars’koho (Tekst prohramy narodovtsiv, pryiniatoi zboramy muzhiv doviria politychnoho tovarystva “Narodna Rada” u L’vovi 25 bereznia 1892 roku).

- Ibid., 9.

- “Nova partiia, ieï prohrama i orhanizatsiia,” Buduchnist’, 15 December 1899.

- Stepan Baran, “Mykola Vasyl’ko (Nekroloh),” Dilo, 8 August 1924: 1–4.

- TsDIA Lviv, f. 309, op. 2, spr. 109, Lyst M. Vasyl’ka do Vil’hel’ma Habsburga vid 24 kvitnia 1917.

- Tadeusz Dąbkowski, Ukraiński ruch narodowy w Galicji Wschodniej, 1912–1923 (Warsaw, 1985), 80.

- TsDIA Lviv, f. 746, op. 1, spr. 6, 5.

- Ievhen Levyts’kyi, Lysty z Nimechchyny (Vienna, 1916), 13.

- P. Mahochi, Istoriia Ukraïny (Kyiv, 2007), 439.

- Mykhailo Lozyns’kyi, Halychyna v rr. 1918–1920 (Vienna, 1922; repr. New York, 1970), 11.

- Ukrainian for “golden gate.”

- Vasyl’ Kuchabs’kyi, Zoloti vorota. Istoriia Sichovykh Stril’tsiv 1917–1919 (Lviv, 1937), 6.

- I. Pater, Soiuz vyzvolennia Ukraïny: problemy derzhavnosti i sobornosti (Lviv, 2000), 74; Nasha platforma (Vienna), no. 1, 5 October 1914: 2.

- For more detail, see chapter 1b in the present volume.

- Wassyl Rassewytsch (Vasyl’ Rasevych), “Außenpolitische Orientierungen österreichischer Ukrainer (1912–1918),” in Confraternitas. Ukraïna: kul’turna spadshchyna, natsional’na svidomist’, derzhavnist’, vol. 15 (Lviv, 2006–7), 623–36.

- Kost’ Levyts’kyi, “S’ohochasnyi stan ukraïns’koï spravy. 1917 rik,” Dilo, 6 January 1917: 1.

- Ibid.

- “Rishennia parliamentarnoï komisiï UPR,” Ukraïns’ke slovo, 20 January 1917: 1.

- Kost’ Levyts’kyi, “Natsiolnal’no-demokratychne storonnytstvo v 1918 r.,” Republyka, 1 April 1919.

- Lonhyn Tsehel’s’kyi, Vid lehend do pravdy. Spomyny pro podiï v Ukraïni zv’iazani z Pershym Lystopadom 1918 r. (New York and Philadelphia, 1960), 33.

- “Z Narodnoho Komitetu,” Ukraïns’ke slovo, 15 February 1918: 1.

- Ukraïns’ke slovo, 20 February 1918: 1.

- Levyts’kyi, “Natsional’no-demokratychne storonnytstvo v 1918 r.,” 1ff.

- “Narodnyi Komitet pro derzhavnyi perevorot u Kyïvi i parliamentarnu krizu v Avstriï,” Dilo, 14 May 1918: 1–4.

- Ibid.

- O. Karpenko, “Lystopadova 1918 r. Natsional’no-demokratychna revoliutsiia na zakhidnoukraïns’kykh zemliakh,” Ukraïns’kyi istorychnyi zhurnal, 1993, no. 1: 18.

- Matvii Stakhiv, Zakhidna Ukraïna. Narys istoriï derzhavnoho budivnytstva ta zbroinoï і dyplomatychnoï oborony v 1918–1923, vol. 3 (Scranton, 1960), 102.

- Valerii Soldatenko, Ukraïna v revoliutsiinu dobu. Istorychni ese-khroniky. Rik 1918, vol. 2 (Kyiv, 20 0 9), 313.

- Vasyl Kuchabsky, Western Ukraine in Conflict with Poland and Bolshevism, 1918–1923 (Edmonton and Toronto, 2009), 24.

- Levyts’kyi, “Natsional’no-demokratychne storonnytstvo v 1918 r.,” 1–2.

- Stepan Baran, “Do istoriï povstannia ZUNR,” Dilo, 6 January 1923: 1ff.

- Levyts’kyi, “Natsional’no-demokratychne storonnytstvo v 1918 r.,” 1–2.

- Baran, “Do istoriï povstannia ZUNR,” 1–2.

- Tsehel’s’kyi, Vid lehend do pravdy, 25.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 26.

- Ibid., 17.

- Ibid., 35.

- Ibid., 36.

- Baran, “Do istoriï povstannia ZUNR,” 1–2.

- Vasyl’ Paneiko, “Pered Pershym Lystopada,” Dilo, 1 November 1928: 1.

- “Viis’kovyi komitet,” Dilo, 1 November 1928: 2.

- Paneiko, “Pered Pershym Lystopada,” 1.

- Ibid.

- Baran, “Do istoriï povstannia ZUNR.”

- Ibid.

- Lozyns’kyi, Halychyna, 27.

- Baran, “Do istoriï povstannia ZUNR.”

- Kost’ Levyts’kyi, Istoriia politychnoï dumky halyts’kykh ukraïntsiv. Na pidstavi spomyniv i dokumentiv (Lviv, 1926), 106.

- O. Krasivs’kyi, Halychyna u pershii chverti ХХ st.: Problema ukraïns’ko-pol’s’kykh stosunkiv (Lviv, 2000), 107.

- Lozyns’kyi, Halychyna, 31.

- Ia. Pelens’kyi, “Peredmova: Spohady Het’mana Pavla Skoropads’koho (kinets’ 1917–hruden’ 1918),” in Pavlo Skoropads’kyi, Spohady (kinets’ 1917–hruden’ 1918) (Kyiv and Philadelphia, 1995), 21.

- TsDIA Lviv, f. 358, op. 3, spr. 166, 36–40.

- Lozyns’kyi, Halychyna, 31.

- Krasivs’kyi, Halychyna u pershii chverti ХХ st., 108.

- Mahochi, Istoriia Ukraïny, 439.

- Levyts’kyi, “Natsional’no-demokratychne storonnytstvo v 1918 r.”

- Soldatenko, Ukraïna v revoliutsiinu dobu, 314.

- Lozyns’kyi, Halychyna, 36 –37.

- Levyts’kyi, Istoriia politychnoï dumky halyts’kykh ukraïntsiv, 131.

- Mykhailo Demkovych-Dobrians’kyi, Ukraïns’ko-pol’s’ki stosunky u ХІХ storichchi (Munich, 1969), 16.

- Lozyns’kyi, Halychyna, 42ff., 58.

- Mieczysław Wrzosek, Wojny o granice Polski Odrodzonej 1918–1921 (Warsaw, 1992), 168.

- Mykola Lytvyn and Kim Naumenko, Istoriia ZUNR (Lviv, 1995), 47.

- Mykola Chubatyi, Derzhavnyi lad na Zakhidnii oblasti Ukraïns’koï Narodnoï Respubliky (Lviv, 1921), 16 –17.

- V. S. Kul’chyts’kyi, M. I. Nastiuk, and B. I. Tyshchyk, Istoriia derzhavy i prava Ukraïny (Lv iv,19 96 ), 177.

- Pavlo Hai-Nyzhnyk, UNR ta ZUNR: stanovlennia orhaniv vlady i natsional’ne derzhavotvorennia (1917–1920) (Kyiv, 2010), 212.

- Mahochi, Istoriia Ukraïny, 444.

- I. Piddubnyi, “Politychne zhyttia Bukovyny 1918–1940 rr.,” in Bukovyna 1918–1940 rr.: zovnishni vplyvy na vnutrishnii rozvytok (Chernivtsi, 2005), 58.

- Mahochi, Istoriia Ukraïny, 445.

- M. Lytvyn, “Stolytsia ZUNR,” in Istoriia L’vova. U tr’okh tomakh, vol. 3 (Lviv, 2007), 25; Christoph Mick, “Ethnische Gewalt und Pogrome in Lemberg 1914 und 1941,” Osteuropa 53, no. 12 (December 2003): 1810–30.

- Lytvyn and Naumenko, Istoriia ZUNR, 126.

- For a detailed account, see chapter 4f in the present volume.

- Stakhiv, Zakhidna Ukraïna, 48ff.

- “Sprawy polskie na konferencji pokojowej w Paryżu w 1919 r.” Dokumenty i materiały, vol. 2 (Warsaw, 1967), 353.

Chapter 2b (132-154) from The Emergence of Ukraine: Self-Determination, Occupation, and War in Ukraine, 1917-1922, by Wolfram Dornik, Georgiy Kasianov, Hannes Leidinger, Peter Lieb, Alexei Miller, Bogdan Musial, and Vasyl Rasevych (University of Alberta Press, 05.11.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.