The political movement responded in many ways to such provocations.

By Graham McKerrow

Retired Journalist

Introduction

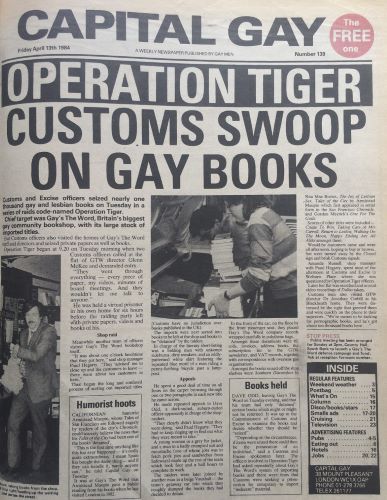

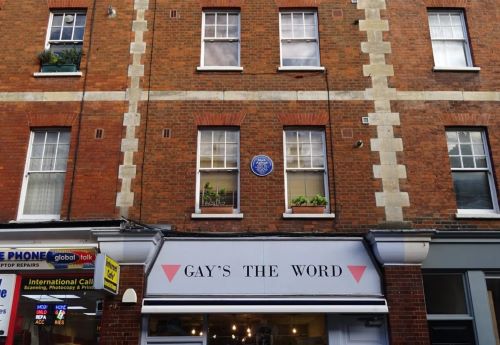

Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise was a British government department from 1909 until 2005,1 when it merged with the Inland Revenue to form HM Revenue and Customs.2 In April 1984, officers from Customs and Excise raided Gay’s the Word, a small independent bookshop in Marchmont Street, Bloomsbury, as well as the homes of two of its directors, and seized thousands of imported books in a move they called Operation Tiger. They subsequently also seized more imported LGBT+ books destined for Gay’s the Word and other booksellers, one of which was put out of business. Only Gay’s the Word challenged the seizures in court to stop the books being destroyed and to defend the right to import LGBT+ books. Customs and Excise then brought 100 charges against nine staff and unpaid directors of the shop in a move that presaged a major censorship trial at the Central Criminal Court.

This happened during a period of right-wing government following Margaret Thatcher’s election victory in 1979 and heightened homophobia from queerbashers in the street, the media, political and religious leaders and the authorities. However, the shop had launched a defence campaign and fund following Operation Tiger and won support from the community, the publishing industry, civil libertarians, politicians and others, and after two and a half years all charges were dropped and the books returned, most of them to the shop, some to the American supplier. This is a story of attempted censorship, a determined and sustained political response and a victory for free speech and an oppressed community.

A New Shop, a New Government, a New Decade

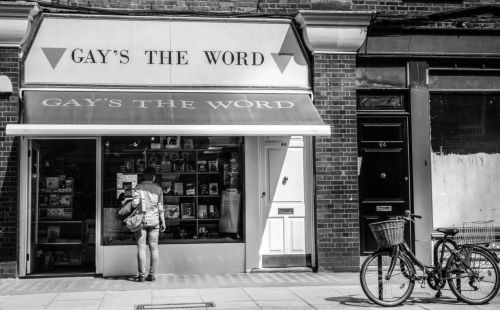

In 1979, Ernest Hole and a small group of friends opened Gay’s the Word bookshop to sell gay and feminist literature at 66 Marchmont Street, London WC1, premises it still occupies today. It took its name from the Ivor Novello musical Gay’s the Word and grew out of a portable collection of books that Hole carried to different venues and events, funded by himself and Peter Dorey who had just received a small inheritance. At the time, LGBT+ books were not generally available in British bookshops but a few radical booksellers stocked some titles, and Gay News, a fortnightly newspaper founded by a collective of activists in June 1972, had an extensive mail-order list. Some gay literature was published in this country but much more was produced abroad, especially in the United States. Onlywomen Press had started publishing in the UK in 1974 and the community’s publishers were to blossom in the 1980s with the founding of Gay Men’s Press and Brilliance Books. The shop had a strict policy not to stock any material that was racist, sexist or pornographic. Gay’s the Word not only stocked its politics on its shelves, it also provided its premises for other lesbian and gay political and community purposes: it was home to the Lesbian Discussion Group, the Gay Men’s Disabled Group, the Gay Black Group, and for many years the Lesbian and Gay Pride Committee held its meetings there.3

Ernest Hole lived in New York for a while between 1968 and 1969 and became friends with Craig Rodwell, who had opened the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in Greenwich Village in 1967. ‘His example inspired me to try and create a similar bookshop in London,’ Hole told Polari magazine. Hole was not alone; lesbian and gay bookstores were being opened around the world with similar political and community motives and as part of a growing cultural surge of writing and publishing. Giovanni’s Room bookstore, named after James Baldwin’s classic gay novel, was opened in Philadelphia in 1973 by three members of Gay Activists Alliance and was bought for $500 three years later by Ed Hermance. When he purchased a building for the shop in 1979, one hundred volunteers helped to renovate it. In the 1980s, Giovanni’s Room became a centre of the city’s response to the Aids crisis because it offered information that local healthcare workers were forbidden to provide. One outlet for its stock and an alternative income stream was the export of books to other booksellers, including Gay’s the Word. Norman Laurilla and George Leigh opened A Different Light bookstore, named after Elizabeth Lynn’s gay science fiction novel, in Los Angeles in 1979, with further stores opening in New York and San Francisco. At their peak, they were running 300 author events per year at the three sites. In 1980 and 1981, Gay’s the Word and Edinburgh’s First of May radical bookshop supported the Lavender Books collective, which ran LGBT+ bookstalls in the city and at conferences and marches around the UK. After dissenting members resigned, Sigrid Nielsen and Bob Orr opened Lavender Menace bookshop in Edinburgh in 1982. So, one can see the earlier mail-order services developing into a network of mutually supportive booksellers, publishers, writers and activists using physical spaces to sell and buy books, to meet, to exchange information and to organise.4

In the same year that Gay’s the Word opened on Marchmont Street, Margaret Thatcher came to power leading a radical right-wing government that would transform British politics in the 1980s. It was a difficult time for British LGBT+ people: queerbashing and murders were rife, as described in a Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) report entitled Attacks on Gay People.5 At the same time, the police used their powers to harass the community. Incidents included police incursions into clubs and saunas, for example Monroe’s in Northampton,6 and several raids on the Gemini in Huddersfield, which was allied with so-called ‘fishing trips’ for suspected homosexuals through people’s private address books and a no-go area of the town.7 Between 30 and 40 police stormed into the Albion sauna in New Brighton, Wallasey.8 Shops were also under attack; for example, the Adelaide bookshop in Cecil Court, near Leicester Square, London, was subjected to repeated and coordinated raids that included the owner’s and his neighbour’s home. The owner and the shop were ordered to pay fines and costs totalling £11,500.9 In London and Manchester, they even used agents provocateurs – young, handsome, male officers dressed in leather jackets and torn denim, known as ‘the pretty police’ – to entrap gay men and charge them with importuning for an immoral purpose.10

The courts were hostile. Divorcing mothers who were shown in court to be lesbian would lose custody of their children.11 Anyone who had killed a gay man could use the ‘homosexual panic’ defence saying that he had made a pass at them, their exit had been blocked so they panicked and killed him. This way they could get a light sentence or be freed.12 People were sacked for being lesbian or gay and when one, John Saunders, a handyman at a school camp in Aberfoyle, was dismissed in the same year that Gay’s the Word opened its door, he took his case to court. In May 1981 the Court of Session in Scotland ruled, in a judgment that set a precedent for the whole country, that it was reasonable to assume homosexuals were automatically a risk to children so it was fair to sack him without needing proof of a complaint about his behaviour.13

The political movement responded in many ways to such provocations. The three leading membership organisations, CHE, the Scottish Homosexual Rights Group and the Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association worked together to lobby parliament and government, demanding an end to laws that discriminated against homosexuals, the introduction of employment protection, and protection from all forms of discrimination against homosexuals.14 Lobbying achieved the decriminalisation of male homosexuality in Scotland in 1980 – this had been achieved in England and Wales in 1967.15 The Greater London Council (GLC) introduced employment protection for its staff16 and gave £450,000 towards a London Lesbian and Gay Centre.17 The activist Jeff Dudgeon defeated the British government at the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled that UIster’s laws against gay male sex broke Privacy Clause 8 of the European human rights code.18

In March 1984, 50 police raided Movements disco at The Bell pub in King’s Cross, London, which was popular with lesbian and gay activists. They were shocked at the scale and nature of the raid,19 although it was no different from the pattern of other police incursions around the country. The following month, there was to be a new development in the State’s harassment of the community: coordinated raids by Customs and Excise on a small community bookshop and the homes of some of its directors who were unpaid volunteers.20

Operation Tiger – Absurd but Serious

At 9.20am on Tuesday 10 April 1984, Customs and Excise launched what they called Operation Tiger,21 when two Customs officers called at the home of Glenn McKee, a director of Gay’s the Word, who had a flat in the Brunswick Centre a few hundred yards down Marchmont Street from the bookshop. They demanded entry and then kept McKee in his home for six hours while they searched the premises. He said, ‘They went through everything – every piece of paper, my videos, minutes of board meetings. And they wouldn’t let me talk to anyone.’ Another team of Customs agents went to the bookshop. ‘It was about one o’clock lunchtime that they got here,’ said shop manager Paud Hegarty. ‘They “advised” me to close up and the customers to leave – there were about ten customers in here.’

Customs and Excise only had jurisdiction over imported titles, not those published in this country, so they first sorted through all the books to separate out the imported ones. They then divided these into two sub-groups: those to be left at Gay’s the Word and those to be detained by Customs. Dave Odd, a dark-suited agent, appeared to be in charge of the raid. The literary shortlisting was supervised by a balding man with unkempt sideburns, dirty sneakers and an oddly patterned shirt, who spent much of his time on all fours on the carpet browsing through a few paragraphs in each book. ‘They clearly didn’t know what they were doing,’ said Hegarty ‘They had to keep ringing up to find out what they were meant to take.’

The Capital Gay report describes what some of the agents were wearing because of the contrast with the uniformed police who usually raided gay premises, and the uniformed Customs officers that people were accustomed to seeing at ports. They took away the impounded books in a beige Vauxhall car, and placed a polythene bag containing the company records on the floor in front of the passenger seat. Till rolls, invoices, address books, the subscription list to the Gay’s the Word newsletter, VAT records and correspondence with overseas gay organisations were all included. The detained books included the feminist novel Southern Discomfort by Rita Mae Brown, the sex guide The Joy of Lesbian Sex by Dr Emily Sisley and Bertha Harris, Armistead Maupin’s classic novel Tales of the City, Gordon Meyrick’s popular novel One for the Gods, the humorous Cruise to Win by Larry Giteck, Paul Monette’s racy adventure story Taking Care of Mrs Carroll, the romantic novel Return to Lesbos by Valerie Taylor, and Sandra Scoppettone’s coming out novel Happy Endings Are All Alike. They would be further evaluated to decide whether they should be ‘seized’ and subsequently destroyed or returned to the shop.22

Amanda Russell, another manager of the shop, spent most of that afternoon at Customs and Excise headquarters in nearby Woburn Place where she was questioned by Operation Tiger officers. Later, her flat was searched and several video recordings of the American soap opera Dallas were seized. Operation Tiger agents also visited Gay’s the Word director, Dr Jonathan Cutbill, at his home in Blackheath, south London. He was a book collector and the agents were soon on the phone to their headquarters saying that they would have trouble finding pornography among the ten thousand books they estimated he had in his house. By this time, they were tired and did not remove any of his property.

The Fightback Starts Immediately

The directors shelved plans to expand the shop into new, larger premises so they could focus on defending Gay’s the Word and the right to import LGBT+ books. There were protests at home and abroad, although the mainstream domestic press ‘maintain[ed] a blanket silence’ on the events, according to Capital Gay. Five days after the raids, more than 150 people attended a public meeting at County Hall, home of the GLC, then run by a controversially lesbian-and-gay-friendly Labour administration. They heard first-hand accounts of the raids and set up action committees to support the shop.23

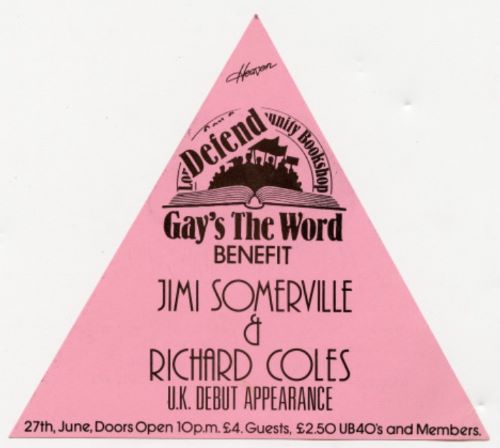

A Defend Gay’s the Word (DGTW) fighting fund raised £500 within the first week, and the Scala cinema at King’s Cross, London, promised the proceeds from a performance. This was to become the campaign that would focus attention on Operation Tiger for the next two years. Delegates to the annual general meeting of the National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL, now called Liberty) on the Sunday following the raid expressed their ‘alarm at this evidence of increasing censorship’ and called for a review of Customs and Excise’s powers of search and seizure. Larry Gostin, NCCL general secretary, wrote to the chancellor of the exchequer, who was responsible for Customs and Excise, and to the home secretary, saying the raid on the shop was ‘a blow to freedom of expression and to the vital work it does of improving accessibility of serious literature of interest to lesbian and gay people. It is an unabashed attempt to financially ruin one of the great educational and social institutions’ of the gay community. The Campaign for Homosexual Equality wanted the matter raised in the House of Commons and asked Frank Dobson, the Labour MP for Holborn and St Pancras and thus the shop’s local MP, to table a question for the chancellor, Nigel Lawson.24

It was now clear that the detained books represented about a third of the shop’s stock, and according to Capital Gay the shop’s tight financial position was a concern because the raids had followed a flood which had destroyed stock at the beginning of the month. Furthermore, about £11,000 worth of stock at wholesale prices had been seized on its way to the shop.25

More than one hundred people demonstrated outside Customs and Excise’s offices in Woburn Place at lunchtime on 27 April 1984. A trade union shop steward at Customs, who refused to give her name, claimed incorrectly that the case was sub judice and refused to meet a delegation, either from the DGTW campaign or from the Civil Service Gay Group. The campaign was starting to attract some media attention with reports in City Limits magazine and the New Statesman and a long letter published in the Guardian. Three and a half weeks after the raids, the defence fund stood at more than £800 and another public meeting was called at County Hall for 20 May.26

In early June, Customs told the bookshop that it was officially seizing 22 of the titles, according to Capital Gay, or 21 according to DGTW briefing note 3, amounting to 221 of the volumes detained in the raids. It said they were indecent and would therefore be destroyed unless the shop went to court to challenge the decision. The threatened titles included One for the Gods, The Joy of Lesbian Sex and a foreign edition of Carter Wilson’s historical novel Treasures on Earth, which had also already been published in the UK.27

Customs issued a circular to people protesting against the raids, saying they had found a single consignment of books imported from the US by Gay’s the Word and had followed this discovery by making inquiries at the shop. ‘It was decided to remove the books and records for examination elsewhere in order to minimise the disturbance. This has been completed and most of the books and records have been returned to the shop.’ Supporters of the shop contradicted these claims. They stated that most of the records and half the books by value had not been returned; and the fact that Customs had private bookshop correspondence dating back three years suggested that Customs’ activities were not a recent event triggered by opening a single parcel of books.28

The parliamentary campaign was also gaining support. Three Liberal MPs, Alex Carlile (Montgomery), the Liberal home affairs spokesman, Simon Hughes (Bermondsey) and Michael Meadowcroft (Leeds West), the assistant Liberal whip, tabled a series of parliamentary questions to the chancellor of the exchequer and the home secretary. They were also seeking all-party support for an early day motion deploring the raid and calling for the return of the seized books, and they organised a meeting at the House of Commons to explain the raids and their implications to other MPs.29

Another action by Customs and Excise was hardly noticed at the time and reported by Capital Gay as only a footnote at the bottom of a longer news report about Gay’s the Word, but it seems more significant in light of subsequent confiscations by Customs officers: on Monday 4 June 1984, Customs detained 120 lesbian and feminist titles in transit from Giovanni’s Room, the lesbian and gay bookshop in Philadelphia that also supplied Gay’s the Word and Lavender Menace, to the London International Feminist Book Fair. All these books were, however, released the following day.30

The Fire Spreads

Seizures of LGBT+ books by Customs and Excise were nothing new. For example, some of the books imported by Gay News for their mail-order customers were seized and destroyed by Customs in the 1970s. Gay News could not trace any pattern in terms of what material was seized and what was permitted, so for some time they refrained from taking the matter to court, deciding to accept the losses as part of the price of running a mail-order book service. However, they did on one occasion challenge a seizure in the magistrates’ court and chose as their battleground what they thought was an innocuous novel called All’s Well That Ends Well. I haven’t found any details about it other than it being at the time on sale at a leading London department store. Gay News lost the case but could see no more logic in the court’s judgment than they could in the decisions of Customs and Excise. Furthermore, the costs of the action were disproportionate to the value of the books, so they refrained from contesting other seizures.31

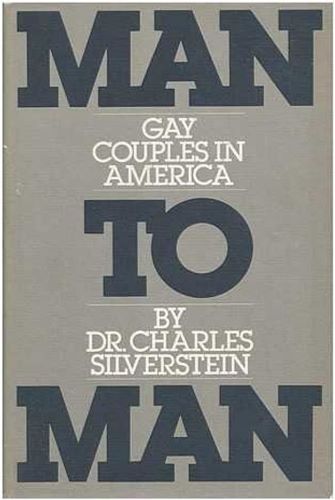

Gay’s the Word swiftly decided that they would stand their ground by challenging all the seizures in court – 22 titles comprising more than 200 volumes. They estimated this would cost up to £5,000, of which the defence fund had raised £2,000. They made clear that ‘we have decided to go ahead with this on a political principle even though it is going to be quite serious for the shop financially.’ However, Customs and Excise escalated the conflict. The mail-order bookseller Essentially Gay, run by the gay activist and writer Terry Sanderson, announced in the week beginning 18 June 1984 that it would have to close after Customs agents seized £1,600 worth of books imported from Giovanni’s Room in Philadelphia and Bookpeople in California. Sanderson said he would not go to court because he did not believe a fair trial was possible. Titles included the guides Men Loving Men by Mitch Walker and The Joy of Gay Sex by Dr Charles Silverstein and Edmund White.32

The following month, Customs surveyors seized a consignment of books sent from Giovanni’s Room to Balham Food and Books Cooperative, an alternative bookshop in south London. Balham Food and Books said they could not afford to challenge the seizure in court.33 Housmans bookshop at King’s Cross, London, announced at the end of July that Customs surveyors had also impounded some of its books, and that the costs of challenging the seizures in court were prohibitive. On 1 August, Customs notified Gay’s the Word that it was seizing 15 copies of Issue 123 of the French gay newspaper Gai Pied. These were intercepted at the port of Dover in June. This spread the seizures from books to newspapers. In a statement, Gay’s the Word said this represented an expansion of the censorship from matters relating to sex and alleged indecency to straightforward political issues.34

In September, it was reported that Customs surveyors at Prestwick airport in Scotland had seized £250 worth of books and magazines on their way to Lavender Menace bookshop in Edinburgh. The titles affected included copies of the magazine Sinister Wisdom, one of the oldest and best-known lesbian magazines, edited at one time by Adrienne Rich. One of the shop’s co-owners, Sigrid Nielsen, commented to Capital Gay: ‘I was stunned when I heard the news; no lesbian publications have ever been seized from Lavender Menace bookshop before. And certainly nothing of this high quality.’35

Since April, there had been seven seizures and detentions of lesbian and gay literature by Customs and Excise surveyors but in September 1984, Mr J.S. England, the chief press officer for Customs, told Capital Gay: ‘There is no campaign against any particular group.’36 The following month, Customs seized 132 titles, amounting to 2,265 items, from Gay’s the Word. Capital Gay reported that this would take the legal costs of challenging the seizures in court up from the previous estimate of £5,000 to about £30,000. The newspaper said this threw the shop ‘into turmoil’, but Jonathan Cutbill was quoted as asking, ‘Can we afford not to fight?’ Capital Gay said these latest seizures were so wide-ranging that they were likely to fuel support for the bookshop because they included works by writers such as Robin Maugham, James Kirkwood, Jean-Paul Sartre and Gore Vidal, and books on health, guides for parents, cartoon books and newspapers.37

In November 1984, Customs surveyors seized 15 copies of The Joy of Gay Sex which were on their way to the Gay Christian Movement (GCM). This was the first time a national gay membership organisation had been subjected to Customs and Excise seizures. Rev. Richard Kirker, GCM secretary, told a DGTW meeting that Customs offered not to prosecute him if he gave evidence against Gay’s the Word. ‘In other words, it was blackmail and I have no intention of giving into that,’ he said. He committed GCM to contesting the seizure, working closely with DGTW and mobilising GCM members to support the campaign. Customs also seized a further five titles, 19 volumes, being imported by Lavender Menace in Edinburgh (its precursor was Lavender Books, the shop Gay’s the Word had supported). This brought the total number of detentions and seizures of LGBT+ consignments since April to ten.38 Some of the seizure notices covered separate consignments of the same titles, and when this was taken into account, Customs surveyors had seized 142 – although some reports say 144 – titles from Gay’s the Word in three actions between April and October 1984.

Criminal Conspiracy Charges

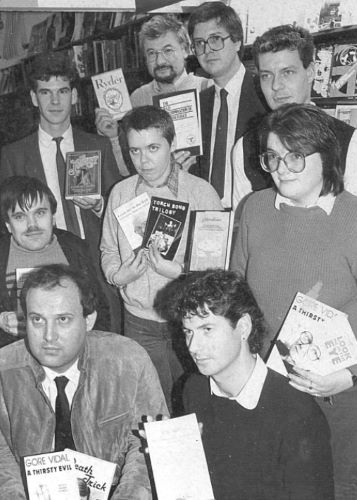

On Wednesday 21 November 1984, Paud Hegarty, the manager of Gay’s the Word, and its eight directors were charged with conspiracy to import indecent and obscene material. The directors were Charles Brown, Jonathan Cutbill, Peter Dorey, Gerard Walsh, Glenn McKee, Amanda Russell, John Duncan and Lesley Jones. Amanda Russell had found new employment so she and the latter two were now former managers of the bookshop.

The defendants all faced identical charges of conspiring to import indecent or obscene material, with six of them facing a further eight, and three of them nine charges of importing named titles that Customs claimed were indecent or obscene. The total of 84 charges would in time grow to be 100 charges against the nine defendants. The scale of Customs and Excise’s legal action set the scene for a major trial at the Old Bailey, which the Guardian, as reported in Capital Gay, compared to the infamous 1960 obscenity trial against Penguin Books for publication of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover.39

Each defendant was charged that:

On divers dates between 1 January 1981 and 1 August 1984 at London and elsewhere [they did] conspire with [each other] and with Ed Hermance [of Giovanni’s Room in Philadelphia] and other persons unknown fraudulently to evade the prohibition on importation of indecent and obscene material imposed by section 42 of the Customs Consolidation Act 1876, that being an offence contrary to section 170 (2) of the Customs and Excise Management Act 1979.

The maximum penalty for each of the charges involving individual titles was two years in prison, a £1,000 fine or a fine of three times the value of the books. The maximum penalty for conspiracy was life imprisonment. The estimated legal costs rose to between £30,000 and £50,000.40

I knew some of the nine defendants before Operation Tiger. Others I met as the case progressed. Here, I want to record a little about them individually and as a group; the sources of this information are the individuals concerned and my own observations. I was not a party to their meetings among themselves or with their lawyers, but while at Gay News and then Capital Gay I interviewed several of them and met others, and when I became one of the campaign coordinators I liaised with them, and on occasion we socialised together. Some became good friends.

Some of the defendants had collaborated before Gay’s the Word was started. Charles Brown, Jonathan Cutbill, Peter Dorey, John Duncan and Paud Hegarty had, like Ernest Hole, been members of Gay Icebreakers, the radical lesbian and gay telephone helpline and befriending collective that another defendant, Glenn McKee, approached for support in the late 1970s. The title ‘director’ may give the impression they were business people but they were unpaid volunteers who guided the shop and worked in it by rota on Sundays. Some of them had painted the premises and built the bookshelves that exist to this day. A looming high-profile case at the Old Bailey and the possibility of severe penalties must have put a great deal of stress on each of the defendants but I never heard any of them express any self-pity or fear, although they voiced anger as Customs increased the pressure with their astonishing array of seizures and charges. All nine displayed dignity and determination throughout their ordeal.

Charles Brown, originally from Lanarkshire, was an economist for British Rail and later a senior civil servant; he maintained a warm, friendly sense of humour throughout; he lived then and still lives with his partner Gerard Walsh.

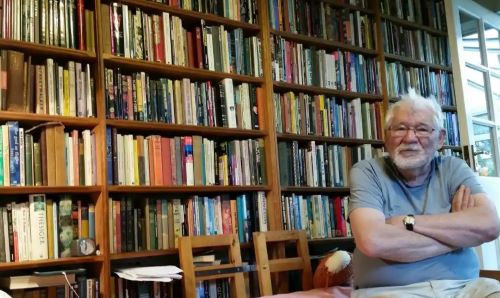

Jonathan Cutbill had been involved with Gay’s the Word from its early days, was an information systems expert at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum, and was an authority on the poet Wilfred Owen. He amassed an unrivalled collection of rare and interesting books on LGBT+ subjects which, upon his death aged 82 in August 2019, numbered about 30,000. These went to the University of London’s Senate House Library.

Peter Dorey funded Gay’s the Word when it was a portable bookseller visiting gay venues and conferences before it found permanent premises. He was a sound technician for the BBC and was perhaps the quietest in a group of strong characters. Peter provided invaluable advice and information for the preparation of this account but before it was published he died in his sleep on the night of 11/12 February 2021 after being ill for several years.

John Duncan was manager of the shop when it recovered from some early commercial stumbles and later went on to be circulation manager of the New Statesman. He had a great sense of humour and fun. He would have been a central figure in the trial because he wrote letters to Ed Hermance of Giovanni’s Room asking for help in avoiding detection by Customs using the ploy of sending ‘ordinary books’ to Glenn’s flat but ‘For all “obscene books” (e.g. JGS, Meat, most Gay Sunshine material, or anything else that could possibly be labelled pornographic) please send to J. Runcie, [delivery address, Duncan’s home in London N1].’ Runcie was the name of the then archbishop of Canterbury. John died aged 32 of Aids-related complications on 18 January 1993.

Paud Hegarty was also a manager of the shop, who after the case was compounded trained as a lawyer but died from Aids-related complications in 2000 aged 45. He was a tall, gentle man originally from the Republic of Ireland with a dry wit and a fine understanding of Marxist theory.

Lesley Jones was the subscriptions manager at Gay News when I met her in 1980. She and Amanda Russell were lovers and it was through Russell that Jones volunteered at Gay’s the Word, where she later became a director. She always had a smile and a kind word. Some years later she emigrated with a new partner to Canada but now lives and works in Leeds.

Glenn McKee was originally from Downpatrick in Northern Ireland and when he came to London he approached Gay Icebreakers. This led to him getting involved in the bookshop where he started the Gay Men’s Disabled Group, which was the first of its kind.

Amanda Russell was one of the funniest, friendliest, toughest lesbians one could hope to meet who, after managing the shop, went to work for Lesbian Line and then moved to Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire. She and Jones started the Lesbian Discussion Group that still meets at the shop on Wednesday evenings, which makes it the oldest such group in existence.

Gerard Walsh, a native Londoner, was an economist and writer for the Economist Intelligence Unit, who lives now as he did then with his partner Charles Brown.

The Case Goes to Court

In March the following year, Customs surveyors at the port of Dover seized a second shipment of the French weekly newspaper Gai Pied on its way to Gay’s the Word, saying that Issue 157 was indecent or obscene.41

The Bookseller magazine had led the way in the mainstream book publishing world with coverage of Operation Tiger across three pages in September 1984, beginning with: ‘The Customs raid on Gay’s the Word bookshop in London, and temporary seizure of much of the stock, will not attract the sympathy of everyone. However, an important principle may be involved.’42 In the spring of the following year, mainstream publishers came to the defence of Gay’s the Word: Penguin Books gave £500 to the defence fund, Gollancz gave £500, Chatto and Windus gave £200, and Faber promised to donate as well. The book publishing world was rallying to the bookshop’s cause. The fund had now surpassed £30,000.43

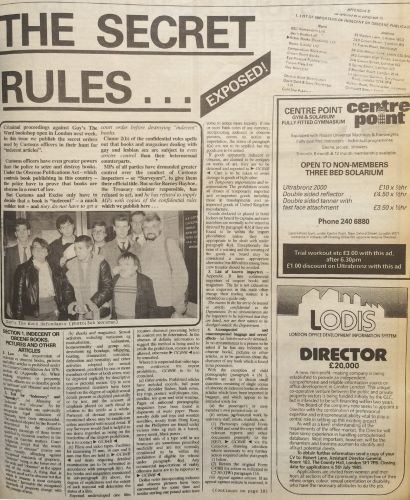

In June, Capital Gay published secret guidelines given by Customs and Excise to their surveyors to help them decide what material should be detained or seized as ‘indecent or obscene’. Members of Parliament had asked for these guidelines to be provided by the government but Barney Hayhoe, the treasury minister responsible for Customs, had refused to supply them to the MPs. The guidelines were leaked to Capital Gay, which I edited, and we published them. The relevant section of the document was Section 1, 2. (b), which listed what Customs regarded as indecent or obscene opening with: ‘Books and magazines. Sexual activities, including variations e.g. masturbation, lesbianism, homosexuality…’ before going on to list a variety of ‘deviations’ such as bondage, whipping, beating and domination.44

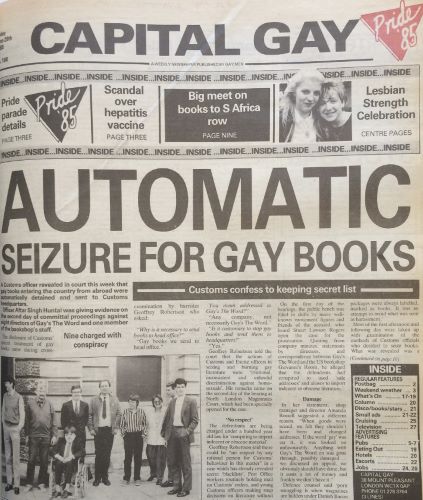

The following week, the committal hearing opened at North London magistrates’ court in Stoke Newington with NCCL handling the defence under their lawyers Marie Staunton and Hilary Kitchen. The defendants had opted for an old-style committal hearing, which meant that the prosecution had to present its entire case with witnesses who could be cross-examined by the defence. Geoffrey Robertson was the barrister for Gay’s the Word. He had previously represented Oz magazine at the famous obscenity trial in 1971, and Gay News when it was prosecuted for blasphemous libel in 1977. Under his cross-examination, Customs surveyors admitted that gay books entering the country were automatically detained and sent to Customs head office.45

One exchange between Robertson and a Customs surveyor called Aftar Singh Huntal went:

GR: Why is it necessary to send books to head office?

ASH: Gay books we send to head office.

GR: You mean addressed to Gay’s the Word?

ASH: Any company, not necessarily Gay’s the Word.

GR: Is it customary to stop gay books and send them to headquarters?

ASH: Yes.46

Stuart Lawson Rogers, prosecuting, alleged that the defendants had conspired to use ‘safe addresses’ and aliases to import indecent or obscene material. One of the defendants, Amanda Russell, gave a different explanation for their behaviour. She said:

When goods were seized, we felt they shouldn’t have been and changed addresses. If the word ‘gay’ was on it, it was looked on unfavourably. Anything with ‘Gay’s the Word’ on was gone through, possibly damaged … we discussed an appeal, we obviously should have done, but it costs a lot of money and frankly we don’t have it.47

Defence counsel said: ‘Porn smuggling is when magazines are hidden under Danish bacon lorries and the like. They are not labelled. Gay’s the Word packages were always labelled, marked as books. It was an attempt to avoid what was seen as harassment.’48

So the legal arguments were clear. There was little disagreement over the facts of what the defendants had done; the dispute was over their motives. The prosecution said they were trying to import indecent or obscene material without being detected; the defence said they were trying to import books and took steps to avoid official harassment targeting lesbian and gay books.

On 3 July, the officer in charge of Operation Tiger took the witness stand. Geoffrey Robertson, for the defence, produced a copy of the previous Friday’s Capital Gay, which reproduced the Customs guidelines on what surveyors should detain. Colin Woodgate, a higher executive Customs officer, refused to confirm that they were the authentic Customs guidelines but, when pressed by the defence barrister, he admitted that they ‘seem[ed] to be’ the guidelines. Capital Gay was shown to the magistrate and became an official exhibit. Woodgate confirmed that all officers were given photocopied guidelines telling them to look out for ‘masturbation, homosexuality, lesbianism and group sex’.49

It emerged that Operation Tiger had been organised at quite a low administrative level, and many of the surveyors who issued seizure notices ‘turned out to be young men of 20 who left school at 16’, according to Barry Scanes, treasurer of the defence campaign. ‘These, it transpired, were the people who decided that poems by Verlaine were “indecent” and had gone through Genet’s Querelle de Brest marking what they considered to be the rude bits.’50 Officers giving evidence said they were given no training or guidance as to legal definitions of indecency, obscenity or literary merit.51

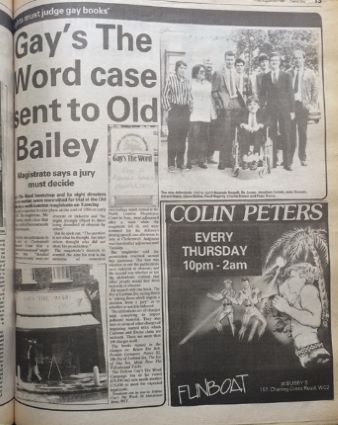

On 20 August 1985 the magistrate, Mr C.J. Bourke, committed the nine defendants for trial at the Central Criminal Court, popularly known as the Old Bailey. He said that the issues were whether or not the publications were indecent, whether or not the defendants would have anticipated that the generality of public opinion would have considered them obscene, and finally he said the judgment should be made according to the views of heterosexuals:

A committed homosexual may consider that detailed accounts of homosexual behaviour in such a way as to arouse homosexual feeling was [sic] proper. He would dispute the classification as indecent or obscene and challenge their description as such. That is not the point. The question is not what he thought, but what others, not of his prediliction [sic] would think.52

In a statement to the court on behalf of all the defendants, McKee said: ‘We are booksellers, not pornographers.’

The Political Campaign

The directors and staff of Gay’s the Word kept the shop open throughout this time while also preparing their legal defence and guiding the political defence campaign. They travelled the country speaking to lesbian and gay groups and others about the case. The DGTW campaign and the defence fund were organised as separate elements, with independent trustees appointed to supervise the fund.

The campaign encouraged letter writing, lobbying, media coverage and occasional street protests, such as those outside Customs headquarters following the Operation Tiger raids, and supporters gathering at the magistrates court for the committal hearing. However, its main thrust was the parliamentary campaign, which aimed to bring political influence to bear on the treasury and, through the treasury, on Customs and Excise itself, as well as to highlight the iniquities of the Customs Consolidation Act 1876 in the hope of achieving reforms to the law.

Defend Gay’s the Word had six aims:53

- The return of Gay’s the Word’s books and records and the personal possessions of its directors and staff; the release of any material detained at point of entry; no further detention of imports to Gay’s the Word or other importers.

- All the charges to be dropped.

- Compensation for lost revenues due to the action.

- To increase public awareness of the action and of HM Customs and Excise powers generally, and to mobilise opposition to both within the gay and lesbian as well as non-gay communities.

- To put the action against Gay’s the Word firmly in the context of overall police and government actions against the civil liberties of lesbians and gay men.

- To lobby for the laws governing HM Customs and Excise to be brought into line with accepted principles of civil liberties and natural justice.

As already stated, the parliamentary campaign started directly after the Operation Tiger raids in April 1984. Within days, CHE had asked Frank Dobson, the bookshop’s constituency MP, to table a question in the House to the chancellor of the exchequer, Nigel Lawson. Larry Gostin, NCCL general secretary, wrote to the home secretary and the chancellor condemning Operation Tiger.54 In June 1984, three Liberal MPs, Alex Carlile, Simon Hughes and Michael Meadowcroft, asked the chancellor and home secretary a series of parliamentary questions about the case. They also sought all-party support for an early day motion condemning Operation Tiger, and they arranged a meeting at the House of Commons during Lesbian and Gay Pride Week to tell other MPs about the raids. This parliamentary activity followed a recent debate in the Commons about the use of so-called ‘pretty police’ agents provocateurs used to entrap gay men, and coincided with CHE lobbying the House of Lords to amend the Police and Criminal Evidence Bill.55

On 12 July, Gay’s the Word was the first subject discussed during Treasury Questions in the House of Commons. In response to questions from Chris Smith (Labour, Islington South and Finsbury) and Simon Hughes, Ian Stewart, the treasury’s economic secretary, said that the government had received 80 letters of protest about the raids including 26 forwarded by MPs, and nine written questions. Dobson said: ‘The bookshop is in my constituency. Will the minister confirm that none of my constituents has complained about it but that many parents in the area are worried about the massive increase in heroin addiction? Does he think that Customs and Excise should give priority to stopping the import of heroin rather than playing the fool with a bookshop?’56

The NCCL stepped up its support for the shop in August 1984, offering the services of its lawyers and making Gay’s the Word one of its two major campaigns – the other being to reinstate trade unions at the government’s communications headquarters.57

In November, the Conservative MP John Wheeler JP (Westminster North) tabled four written questions about the seizures, but Barney Hayhoe gave what Capital Gay called ‘evasive answers’. Christine Mackie MEP (Labour, Birmingham East) visited Gay’s the Word and promised to raise the matter in the European Parliament.58 On 13 November, an all-party group of MPs meeting at the House of Commons offered its full support to the defence campaign. They decided to table questions to the attorney general and the treasury, and to ask Nigel Lawson to receive an all-party delegation.59 The GLC’s Police Committee published on 12 March a report critical of Customs’ ‘harassment and censorship’ of lesbian and gay bookshops and called for a government inquiry into the role of Customs and Excise.60

In June 1985, the shadow home secretary, Gerald Kaufman, issued a statement to coincide with the committal hearing:

I would like to express my strong support for Gay’s the Word bookshop in the difficulties in which it is involved. Enormous amounts of public money have been spent in order to interfere with the right of British citizens to read what they choose, in many cases books which are freely and uncontroversially available elsewhere. At a time of a massive crime wave in London, with an unfortunate lack of success by the police in coping with that crime wave, the authorities should direct their attention to muggers and burglars rather than authors and booksellers.61

Frank Dobson and Chris Smith spoke at a press conference organised by the defence campaign that same week. According to Capital Gay, Smith said he could not understand Customs’ priorities. Over the previous five years the department had shed 1,000 jobs. With alarm growing over international drug trafficking, the government was now trumpeting that it had employed a mere 160 new officers. And yet at least 37 officers had been involved in the Gay’s the Word action.62

As already demonstrated, the shop and the defence campaign received support from the book publishing industry. There were also letters of support and donations from writers such as Angela Carter and Gore Vidal,63 and Sir Angus Wilson, president of the Royal Society of Literature, issued this statement to coincide with the committal hearing:

As a writer, I have had to protest sadly often against the persecution of writers in many parts of the world. It is utterly disgraceful that in this civilised country we should have to protest against censorship of reading material. It is shameful that prosecutions can still be brought by individuals or officials under long-outdated laws. It is intolerable that officials should have such wide-ranging powers of indiscriminate seizure of books. It is even more intolerable that those powers should be exercised.64

The Central Criminal Court announced that the defendants would face trial starting in October 1986. In January 1986, David Northmore, an activist with Kent gay groups and the NCCL, was appointed as coordinator of the defence campaign, a full-time job and the first paid staff post.65 The following month, I left my position as co-editor of Capital Gay to join the defence campaign as joint coordinator.66 The campaign involved countless numbers of people around the world writing letters of protest, organising benefits and sending personal donations. Also taking part were volunteers at the campaign office in the shop’s basement, allies in the media and politics, contributors to a one-hour BBC documentary, and even a London theatre director who was writing and recruiting cast and orchestra for Operation Tiger – The Musical, which was scheduled to start at the Piccadilly Theatre just before the trial.

The Law Takes a Strange Turn

There was no pause in Customs’ policy of seizures while both sides prepared for the Old Bailey trial. In January 1986, five copies of Man to Man, a sociological research work by Dr Charles Silverstein, were intercepted at Mount Pleasant sorting office in north London en route from Giovanni’s Room to Gay’s the Word. Three previous consignments of this title had arrived safely at the shop, although one appeared to have been tampered with and resealed. The academic Mary McIntosh, a member of the Home Office’s Policy Advisory Committee to the Criminal Law Revision Committee, told Capital Gay: ‘I don’t see why this book has been seized by Customs and Excise. Far from doing any harm it is an educational and informative book.’67

But then something unusual happened in another court case that was seemingly unconnected with Gay’s the Word, but may have had a profound effect on the case against the shop. A judgment involving the importation of sex dolls was appealed to the European Union in Luxembourg, which ruled that public morality was no grounds for banning the importation of goods that were otherwise allowed to be produced and sold in the country concerned. Customs surveyors at Heathrow had seized 490 West German inflatable dolls in 1983. The importer, a company called Conegate, which ran a number of sex shops in the UK, took the government to court, arguing that the Customs action broke the European Economic Community’s rules on the free movement of goods. The Treaty of Rome allowed governments to ban the importation of goods in defence of public morality but the European judges ruled, on 11 March 1986, that a member state could not argue that it was prohibiting the importation of certain goods in order to defend public morality if its own legislation allowed the manufacture and marketing of such goods in its territory.68

Most of the titles seized from Gay’s the Word had been imported from the United States but obviously it would be possible to import titles from America via another European state, so the Conegate ruling could affect imports from all countries. The judgment meant that imports would be subject to the tougher test of obscenity contained in the Obscene Publications Acts 1959 and 1964, which applies to domestically produced material. The test for indecency under the Customs Consolidation Act is defined as material likely to offend the man in the street, whereas the test for obscenity is that it must ‘tend to deprave and corrupt’ those likely to see it, and the obscenity acts allow publications that are ‘for the public good’ in the interests of science, literature, art or learning, so defendants can call expert witnesses to testify to the importance of works in these respects.69

A week after the judgment, the Labour MPs Chris Smith and Jo Richardson, who was a member of the party’s National Executive Committee, met Peter Brooke, the newly appointed treasury minister responsible for Customs, to ask him to instruct treasury lawyers to study the Luxembourg judgment. Brooke promised that officers would stop opening every package addressed to Gay’s the Word, and he also promised to reconsider the seizure of Man to Man.70 However, in June, Customs officers at Gatwick broke their own rules in relation to allowing the importation of material for personal use, when they seized a copy of the American gay newspaper The Advocate and some soft porn magazines from an unfortunate Hackney schoolteacher returning from a holiday in the United States.71

The barrister Richard du Cann drafted a letter to Customs and Excise to be sent by the NCCL’s legal officer, Marie Staunton, who was acting as solicitor for the defendants. It said that in light of the Conegate judgment:

- The case should be withdrawn against all the defendants.

- The bookshop’s costs should be paid from central funds.

- The titles should be divided into those said to infringe the Obscenity Acts and those which do not.

- Those said to infringe the Obscenity Acts should be returned to the sender in the United States.

- The other titles should be released to the defendants.

- The defendants will not reimport any of the titles in 4 above without first telling Customs.72

The Charges Are Dropped, the Books Are Returned

On 27 June, more than two years and two months after the Operation Tiger raids, the defendants and campaigners learned a new legal term when HM Customs and Excise informed lawyers for the defendants that the case would be compounded. ‘Compounded’ meant that all one hundred charges against all nine defendants had been dropped. Customs also said they would return all the books; 19 of the titles were to be sent back to Giovanni’s Room in Philadelphia because Customs believed they were obscene under the Obscene Publications Acts, but the remainder of the 142 titles seized were to be handed over to Gay’s the Word. Customs said they would apply the test of obscenity when deciding what to seize in future.73

The shop’s window display of the released books now on sale was as happy a sight as the defendants’ faces while sipping champagne with Marie Staunton and campaign workers within. And it was announced in time to add a sparkle to that year’s Pride Parade on 5 July.74 More than 2,000 people attended a Victory Ball at the Hippodrome nightclub at Leicester Square later that month, including MPs, at least one MEP and David Whitaker, editor of the Bookseller.75

In August, the Rev Richard Kirker, secretary of the Gay Christian Movement, went to Customs’ offices in Woburn Place, London, WC1, to collect 15 copies of The Joy of Gay Sex that had been seized by surveyors.76 New deliveries of 21 mailsacks containing about 2,000 volumes of 100 titles arrived from America at the bookshop in November, and more were anticipated. The shipments included some new titles as well as books that Customs had tried to ban from the UK, such as The Joy of Lesbian Sex, The Joy of Gay Sex and other sex manuals and studies.77

In the years that followed, Gay’s the Word was involved in a series of court cases aimed at clarifying the law. These started with the importation from the Netherlands in October 1986 of the books Men in Erotic Art (about which I have found no details), Men Loving Men, Men Loving Themselves by Jack Morin PhD (in which 12 gay men discuss their attitudes to masturbation), and the erotic fiction My Brother My Self, Roman Conquests and Below the Belt, all by Phil Andros (a pen name of Samuel Steward). Following the Conegate judgment and the compounding of the case against Gay’s the Word, it was unclear if the ‘public good’ defence and the use of expert witnesses could be employed to defend imports. The case reached the Court of Appeal, which ruled in December 1988 that the ‘public good’ defence was not applicable to imports.78

Documentary evidence is hard to find, but a plan had been mooted, which I believe was agreed in principle with Customs and Excise, for Gay’s the Word to reimport in batches the titles Customs had returned to the US, notifying Customs in advance, so that the law relating to allegedly obscene imports could be tested in court. This would have been in accord with point 6 above in the letter from Marie Staunton to the solicitor representing Customs. It seems likely that this is what led to the judgment involving these titles, but I have not found proof of this. Sources detailing what happened would be welcome.

Discussion

Operation Tiger highlighted the extraordinary powers of HM Customs and Excise, which shocked the defendants and their supporters and can be summarised as follows:

- The Writ of Assistance is like a search warrant, except that one is issued at the start of each reign of a monarch and lasts until six months after the reign ends. It allows Customs officers to enter any building by force and search and seize any goods liable to forfeiture. This far exceeds powers granted to the police and, unlike a search warrant, is not supervised by the courts.79

- Seized books are in effect ‘guilty’ until proven innocent; they are destroyed unless the importer takes the case to court to challenge Customs’ decision.80

- Until the Conegate judgment and the compounding of the case against Gay’s the Word, the law treated imported goods differently from goods produced in the UK. Imported goods were banned if they were indecent, that is, if they would offend the man in the street, whereas goods produced in the UK would only be banned if they were obscene, and that was defined as tending to deprave and corrupt those likely to see it, which was harder to prove. Domestically produced goods could also be defended if they were ‘for the public good’ and expert witnesses could be called.81

It is clear from HM Customs and Excise’s actions against a variety of importers that they tried to shut off the importation of all lesbian and gay books. They may not have started with that intention: as Operation Tiger unfolded, Customs staff were surprised by the character of Gay’s the Word and the nature of its stock – books with words. They were clearly more accustomed to dealing with photo magazines. Whereas some book importers like Gay News carried the loss of seizures, and some like Housmans bookshop and Balham Food and Books Cooperative could not afford to go to court, while others like Essentially Gay were driven out of business, Gay’s the Word stood and fought the case. In response, Customs escalated the case with more seizures and the unprecedented array of criminal charges.

This raises the first two unanswered questions about the case: why did Customs start it and why did they escalate it? As well as looking within Customs for the answer, it is worth recalling the homophobic attitudes of the time and that the UK had a right-wing government under Margaret Thatcher – the notorious Section 28 banning local authorities from promoting homosexuality as ‘a pretend family relationship’ was to follow.

A third important unanswered question remains: why did Customs compound the case? In 2018, when I asked Charles Brown and Gerard Walsh why they thought the case was dropped, they immediately said ‘The defence campaign’. They added that they thought DGTW’s identification of and publicising of a series of absurd and humorous inconsistencies in policy embarrassed senior civil servants and ministers, which was ‘a cardinal no-no in the civil service’. The suggestion is that Customs backed down to avoid further public humiliation. The change of minister at the treasury, when Peter Brooke took over responsibility for Customs and Excise from Barney Hayhoe, may also be relevant. Any new minister will be briefed on what is in their in-tray and will want to ditch anything that could prove embarrassing. The judgment of the Luxembourg court in the Conegate case may have been the reason for the compounding, or it could have been a useful excuse for a worried minister. It is notable how closely Customs’ settlement followed the defence solicitor’s suggestions in her letter about the implications of the Conegate judgment, except that the defendants’ costs were not paid from central funds.

I have tried to find the answers to these questions but my enquiries to what is now HM Revenue and Customs were redirected to the National Archives. My online searches on the National Archives website, assisted by an enthusiastic and knowledgeable archivist providing online ‘chat’ assistance, failed to find anything useful. I have received no reply to my letters to Peter Brooke, who is now Baron Brooke of Sutton Mandeville. This research is far from exhaustive and I hope that others will have more success explaining why this case started, why it escalated and why it ended.

It is clear that Gay’s the Word became a key part of a growing political movement and of the LGBT+ literary world, locally and internationally. It formed part of an ecosystem of cooperation and exchange that enabled our emerging community to communicate and organise in new and more effective ways about an array of pertinent social and political subjects, and to provide the best information to those affected by a growing health crisis. It is also clear that the authorities’ response was to mount an escalating series of actions that seemed intended to close booksellers (as happened with Essentially Gay and threatened to happen with Gay’s the Word), or at the very least to intimidate them. One can imagine the effect a successful prosecution of a hundred charges against nine people at the Old Bailey would have had on Gay’s the Word and other booksellers.

Endnotes

- I thank Jim MacSweeney, Gay’s the Word’s manager for the last 30 years, for information and advice in preparing this account and the presentation that preceded it, and for access to Gay’s the Word’s archive. I am also grateful to Charles Brown and Gerard Walsh for information and original source material from their archive, Amanda Russell, Lesley Jones and Peter Dorey for advice and information, and Andrew Lumsden, a trustee of the defence fund, for advice and encouragement. Thanks also to Leila Kassir and Richard Espley of Senate House Library for enabling me to record these events, and for their patience and guidance, and to my partner Marc Ennals for his patience and advice.

- The Commissioners for Revenue and Customs Act 2005, London. See <http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/11/contents> (accessed 9 Apr. 2020).

- Ernest Hole, ‘The birth of Gay’s the Word’, Polari 17 Jan. 2012, online <http://www.polarimagazine.com/features/birth-gays-word> (accessed 9 Apr. 2020) and Bookseller, London, 22 Sept. 1984, 1331.

- Giovanni’s Room records c. 1975–91, Ms Coll 17, John J Wilcox Jr LGBT Archives, Philadelphia; Tyler Gillespie, ‘The last day at Giovanni’s Room, America’s oldest gay bookstore’, Rolling Stone, New York, 21 May 2014; ‘Lavender Menace returns: a short history’, <https://somewhereedi.org/lavender-menace-returns> (accessed 9 Apr. 2020); Sam Whiting, ‘A Different Light bookstore in Castro closing’, 22 Apr. 2011, <https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/A-Different-Light-gay-bookstore-in-Castro-closing-2374151.php> (accessed 9 Apr. 2020).

- Gay News, 198: 1, 9.

- Gay News, 199: 5.

- Gay News, 209: 1.

- Capital Gay, 28 Jan. 1983, 1.

- Capital Gay, 4 Sept. 1981, 1.

- Capital Gay, 27 Jan. 1984, 1.

- Gay News, 193: 5.

- Gay News, 197: 14.

- Gay News, 215: 3.

- Gay News, 193: 3.

- Gay News, 202: 3.

- Capital Gay, 18 Sept. 1981, 1.

- Capital Gay, 4 March 1983, 1.

- Capital Gay, 23 Oct. 1981, 1.

- Capital Gay, 16 March 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 13 Apr. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 13 Apr. 1984, 1 and ‘Defend Gay’s the Word Briefing Note 1’ rev. May 19.

- Capital Gay, 8 June 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 20 Apr. 1984, 1.

- Ibid.

- Bookseller, 22 Sept. 1984, 1330.

- Capital Gay, 4 May 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 8 June 1984, 1; ‘DGTW Briefing Note 3, Seized Titles’, rev. May 1985.

- Capital Gay, 8 June 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 15 June 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 8 June 1984, 1.

- Written statement by Charles Brown to the committal hearing, June 1985, 7 and oral statement by Michael Mason, news editor in the 1970s, to Charles Brown on 18 June 1995, and recorded in an undated witness statement.

- Capital Gay, 22 June 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 20 July 1984, 3.

- Capital Gay, 3 Aug. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 14 Sept. 1984, 3.

- Capital Gay, 21 Sept. 1984, 5.

- ‘DGTW Briefing Note 3’ rev. May 1985, and Capital Gay, 12 Oct. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 9 Nov. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 30 Nov. 1984, 3.

- Capital Gay, 30 Nov. 1984, 3.

- Capital Gay, 29 March 1985, 1.

- Bookseller, 22 Sept. 1984, 1330.

- Capital Gay, 24 May 1985, 1.

- Capital Gay, 21 June 1985, 17.

- Capital Gay, 28 June 1985, 1.

- Capital Gay, 28 June 1985, 1.

- Capital Gay, 28 June 1985, 1.

- Capital Gay, 28 June 1985, 1.

- ‘GTW defendants kept waiting’, Capital Gay, 5 July 1985.

- Letter from Barry Scanes to Gay’s the Word supporters, 1 Aug. 1985.

- ‘Customs officers in the dark on indecency’, Guardian, 25 June 1985.

- Note of Committal, Mr C. Bourke, 20 Aug. 1985.

- ‘Defend Gay’s the Word Briefing Note 8 revised May 1985’.

- Capital Gay, 20 Apr. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 15 June 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 20 July 1984, 3.

- Capital Gay, 10 Aug. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 9 Nov. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 16 Nov. 1984, 1.

- Capital Gay, 29 March 1985, p. 1.

- ‘A statement from Gerald Kaufman’, 21 June 1985.

- Capital Gay, 28 June 1985, 10.

- NCCL press release, ‘The literary trial of the eighties’, 17 June 1985, London.

- ‘A statement from Sir Angus Wilson, president of the Royal Society of Literature’, 18 June 1985, London.

- Capital Gay, 17 Jan. 1986, 9.

- Capital Gay, 28 Feb. 1986, 1.

- Capital Gay, 14 March 1986, 1.

- ‘European court bars a ban on sex dolls’, Guardian, March 1986, and ‘European Law report’, The Times, 12 March 1986.

- Bookseller, 22 Sept. 1984, 1331; Capital Gay, 21 March 1986, 3; ‘No “public good” defence to seizure of obscene imports, Law Report’, Independent, 13 Jan. 1989.

- Capital Gay, 28 March 1986, 9.

- Capital Gay, 6 June 1986, 1.

- Letter from Marie Staunton to Mr Worrall, solicitor, HM Customs and Excise, 3 June 1986.

- Capital Gay, 4 July 1986, 1.

- Capital Gay, 4 July 1986, 1.

- Capital Gay, 25 July 1986.

- Capital Gay, 22 Aug. 1986, 1.

- Capital Gay, 21 Nov. 1986, 3.

- ‘No “public good” defence to seizure of obscene imports, Law Report’, the Independent, 13 Jan. 1989.

- Customs and Excise Management Act 1979 section 161 London.

- Capital Gay, 8 June 1984, 1.

- ‘No “public good” defence to seizure of obscene imports, Law Report’, Independent, 13 Jan. 1989.

Chapter 6 (91-117) from Queer between the Covers: Histories of Queer Publishing & Publishing Queer Voices, edited by Leila Kassir and Richard Espley (University of London, 06.21.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.