Abolitionists pointed to example after example of horrific violence against enslaved people.

By Dr. Trevor Burnard

Professor of History

University of Hull

Atlantic slavery was a violent institution. The Atlantic slave trade was even more violent. I hardly need to point out this basic fact. An essay about slavery and the slave trade can easily turn into a sickening litany of appalling acts of violence meted out by slave owners towards enslaved people and the less frequent but often equally violent response of enslaved people undertaking acts of resistance to enslavement, including armed revolt. Luxuriating in the violence of slavery is an easy trap for historians to fall into. Walter Johnson, for example, in an otherwise fine book on slavery in the antebellum Mississippi Valley, reaches for sensational language in describing the customary violence of slavery in this period and place. He layers evocative words – slaveholders ‘screaming execrations’, slaves ‘pleading, shrieking, moaning, crying out for mercy’, omnipresent torture where whipped slaves expressed themselves in ‘choking, sobbing, spasmodic groans’ – and uses extensive bodily function imagery to try and evoke in the reader an emotional response about the horrors of nineteenth-century American slavery like that which abolitionists of the time tried to inspire in their readers, in the Victorian age of sentimental reading. The American South in this and in other recent interpretations, was founded on ‘blood, milk, semen and shit’.1

Similarly, Edward Baptist piles on example after example of horrific violence against enslaved people to make the argument that it was calibrated torture, as inflicted on the cotton plantations of the nineteenth-century American South, that allowed the Industrial Revolution to break through ‘the resource constraints that had imprisoned previous civilizations in a Malthusian cul-de-sac’. He uses the metaphor of a ‘whipping machine’ to argue that the discipline of torture as ‘a technology for controlling and exploiting human beings’ created a ‘vast archipelago of slave labor camps’ where the ‘whipping machine’ made slaves endure an ‘unprecedented level and quality of field labor’ in a ‘dynamically evolving technology of measurement, torture and forced innovation’.2

The problem with this highly emotional language, as Philip D. Morgan argues in a critical review of Johnson’s book, is not just that ‘rhetoric often substitutes for analysis’, but that ‘the effect of the piling on of horrors and the shock value of the imagery is the reverse of the one intended’.3 Such language hardens rather than softens the reader to the violence of slavery, especially when acts of brutality are catalogued and repeated at length, making it hard to engage fully with the subject. What is more important than enumerating the everyday and extraordinary violence in the Atlantic slave system that began in the mid fifteenth century, before Columbus’s voyages to the New World, and which lasted until 1888 when Brazil became the last society to abolish slavery, is to analyse the meanings for planters, traders, and enslaved people of the constant violence that enveloped this system.4 I use violence as an analytic category in order to demonstrate how brutality, violence, and death were not mere by-products of the extremely lucrative early modern plantation system but were the sine qua non of that plantation world.

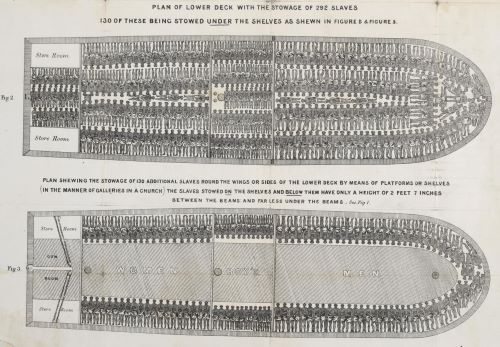

This approach requires understanding the visceral meaning of the systemic vio-lence that was exerted against African people. That violence happened first in Africa as they were loaded onto slave ships – James Stanfield in a poem on ‘the Guinea Trade’ described them as part of a business that was a ‘vast machine’ that while ‘assum[ing] the honours of a honest trade … had, beneath a prostituted glare [a] poison’d purpose’.5 It continued in the Americas, where Africans were transformed into slaves and were worked relentlessly, especially on sugar plantations, where conditions were harsh – Caribbean slaves endured the worst demographic experiences of any enslaved peoples, with annual population attrition due to high mortality rates being consistently in the negative throughout the eighteenth century. And it persisted into the nineteenth century with legacies that continue into the present during what scholars now term a ‘second slavery’, in which new market-oriented forms of slavery were ‘parts of a distinct cycle of economic and geographic expansion of the capitalist-world economic processes of industrialization, urbanization and the restructuring of world markets that occurred as merchant capitalism turned into industrial capitalism’.6

It is important to stress the long-lasting nature of slavery and its adaptability to modernity. The violence of slavery and the slave trade in the Atlantic world was not an atavistic throwback to pre-modern times that was thankfully ended as Enlightenment values and disavowal of violence as a means of conflict resolution became more prevalent in Atlantic societies in Europe and the Americas.7 The fundamental definition of slavery remains constant from its origins in the ancient world to its criminalized presence today – it is the complete and exploitative control of one person (the slave) by another (the slaveholder) in which the slave is treated as property. That definition allows us to know that slavery did not necessarily end with legal declarations of slave emancipation and that it is intimately tied up with coercion and thus with violence.8 Being a slave was not just physically violent; it was psychologically devastating. It is for this reason, as much as more obvious forms of violence, that so many enslaved people – depressed by the reality of their hopeless-ness in a system from which they were unlikely to escape physically unscathed – turned to suicide as one release from their predicament.9

One reason to avoid an excessive concentration on describing lurid aspects of violence in slavery and instead examine violence as an analytic concept, is that focusing on acts of violence can resemble voyeurism – perhaps even have a pornographic quality – in an approach which has a long and troubled history in abolitionist literature. One way in which anti-slavery discourse might be enlivened was to sensationalize and sexualize the whip, the most potent symbol of white authority in the slave colonies of the Americas. Karen Halttunen dubs such prurience the ‘pornography of pain’; this sensationalist approach can be overdone as much in present-day scholarship as in abolitionist literature. Zoe Trodd raises the issue precisely in an examination of prominent tropes, such as the kneeling slave of the Wedgwood medallion and the scourged back of an antebellum American enslaved man. She suggests that it is time for these images to be dropped. Urging contemporary anti-slavery artists to try and find ‘a less abusive usable past’, she argues that scenes of whipping too often put ‘slaves on display, reaching for shock value but risking sensationalism and objectification’.10 I am guilty myself of such sensationalism. My biography of Thomas Thistlewood, an English migrant who lived in Jamaica between 1750 and 1786 and whose extensive diaries provide a rare first-hand insight into the lived experience of slavery, albeit from the viewpoint of a master, tries to portray Thistlewood in the round, as a keen amateur scientist, avid reader, and man of the Enlightenment as much as a brutal and sadistic sexual predator and vicious slave manager. But it is my description of the worst examples of Thistlewood’s violence towards slaves, notably his invention of a punishment he called ‘Derby’s Dose’, in which an enslaved man defecated into another slave’s mouth which was then gagged shut, that attracted most attention in reviews and popular repetition.11

I address here the point of violence in Atlantic slavery and the slave trade and how the incidence of violence in these institutions varied over time. First, was violence central or incidental to the ideology of enslavement in the Atlantic world, and if so, to what extent did slavery underpin the whole character of Atlantic slave societies? Second, was violence effective in the way slave owners treated and controlled enslaved people, especially in those slave societies in the Greater Caribbean, north-east Brazil, and parts of the more southerly regions of the American South where the demographic balance between enslaved blacks and free whites was most heavily weighted in favour of blacks? Was it also effective for enslaved people on the relatively rare occasions when they contested the circumstances they found themselves in through active acts of resistance and rebellion?

Violence within slavery was foundational, purposeful, and so central to slavery that getting rid of it or even lessening its incidence or intensity threatened the whole basis of masterly dominance over enslaved people. Violence also generally produced efficacious results for slave owners in respect to how they maintained control over their enslaved property, how they were able to employ violence while not impeding their capacity to use slaves to make money for themselves, and how they kept themselves secure in societies in which they were often heavily outnumbered. However, it was less efficacious in convincing their rulers in Europe or their more powerful compatriots in non-slaveholding parts of their nation that their authority over their slaves was legitimate. The violence of Atlantic slavery and the slave trade was so obvious to everyone and so extreme in its many manifestations, especially when news of slave revolts and their suppression reached other places, that it provoked consternation among populations increasingly outraged about the use of violence to control people: a growing hostility to what antebellum northerners in the United States called with disdain ‘the slave power’.12

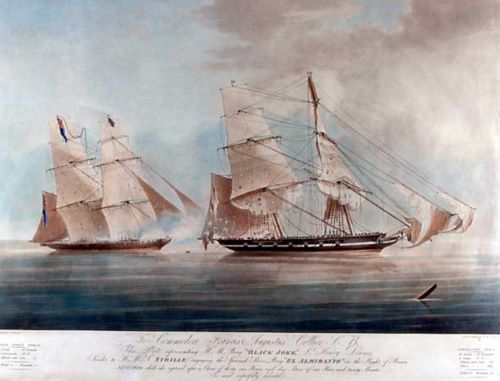

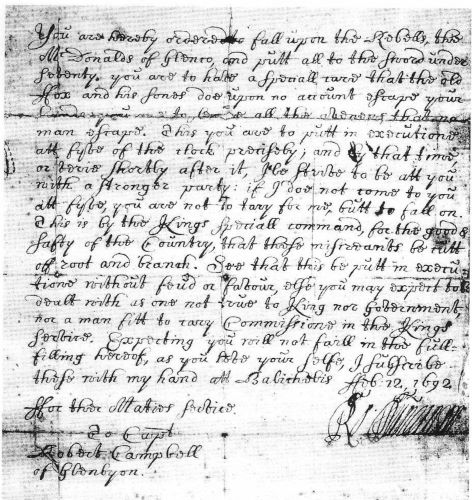

Perhaps the most dramatic manifestation of outrage over violence in slavery and the slave trade came in the 1780s, with an infamous case of murder in the slave trade in 1781. A subsequent court case in Britain in 1783 about this murder percolated into an embryonic abolitionist movement, which erupted in 1787–88 as the biggest social reform movement in British history, leading to the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807. Sailors on the Zong either deliberately or by accident found themselves leagues distant from the western shores of Jamaica in November 1781. They hatched a plan that they later claimed arose out of necessity to prevent the possibility of captive Africans revolting and taking over the ship. It involved murdering 132 Africans by throwing them overboard. Such an act of violence was hardly unusual in the slave trade. What brought the case to public attention, however, was that the crew of the Zong had the idea of claiming insurance for the financial losses they had incurred in murdering African captives. The underwriters demurred and refused to pay, whereupon the ship owners sued for financial restitution. The abolitionist Granville Sharp was alerted to this civil case by a black abolitionist, Oladuah Equiano, and was so outraged at the inhumanity by which a case of murder was treated as an instance of insurance fraud that he publicized the case. Although initially the British public were not very interested, by the mid 1780s they came to see the Zong as indicative of the essential wickedness of the slave trade. What was particularly dreadful about this case, abolitionists like Thomas Clarkson and James Ramsay insisted, was that it was carried out by British sailors on a British ship and resulted in a case in a British court, decided inconclusively and, it was argued, immorally by a famous British judge, Lord Mansfield. In 1788, Clarkson wrote of the Zong that it was an event ‘Unparalleled in the memory of man … and of so black and complicated a nature, that were it to be perpetuated to future generations … it could not possibly be believed’.13

The role of violence as exercised by enslaved people against slave owners is an especially ambivalent historical issue. On the one hand, it is difficult to see this vio-lence as anything other than the understandable response of people pushed beyond endurance against oppression, using the tools that they had at their disposal, given that the powers of the state were all aligned on the side of their oppressors. On the other hand, these acts of violence removed the moral upper hand from enslaved people, confirming, usually unfairly, to their erstwhile supporters in Europe and North America, that slave owners’ assertion that enslaved people were barbarians was essentially correct.14

More to the point, violence employed by enslaved people seldom worked in the ways that slaves wanted. When enslaved people raised their hands against their masters, they were invariably killed and their friends and families were punished. The successful slave insurrection in Haiti starting in 1791 has become the emblem-atic example of slave rebellion in the Atlantic world; but Haiti was the exception, not the rule, in a world where most emancipations occurred through legislative fiat from outside forces rather than through the actions of the enslaved. A more typical slave rebellion was Tacky’s Revolt in Jamaica in 1760, a major slave rebellion involving thousands of slaves that resulted in the deaths of tens of whites and hundreds of blacks. Unlike the Haitian Revolution, Tacky’s Revolt was put down by the Jamaican state. Their revenge was immediate and gruesome. Rebel leaders were put to death by slow fire and by hanging in gibbets until they starved to death, while hundreds of slaves were transported to British Honduras. White Jamaicans learned from their near-death experience in 1760 that if they were sufficiently reso-lute against any sign of slave rebellion and were prepared to use extreme violence to defend planter prerogatives, their safety would be secured.15 So too, planters took their revenge against slave rebels in the aftermath of the Berbice Rebellion of 1763, which was a major colony slave rebellion in which practically all enslaved people were involved as an apparently united force against the Dutch state and which resulted in rebel slaves taking over the colony for a remarkably long period of time. When the Dutch regained the colony in late 1763 they took their revenge in the usual fashion, executing 128 rebels, in often gruesome ways, and punishing through whippings and the transportation of thousands more.16

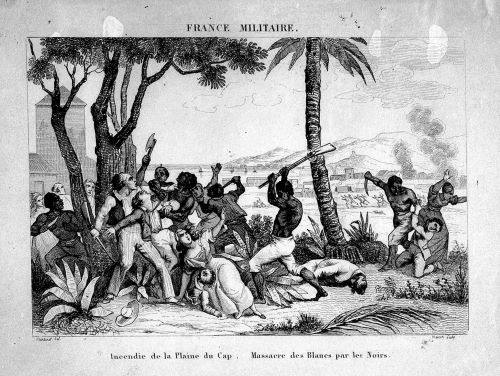

The major counterexample to this sad record of violent slave resistance resulting in more violence from a resurgent master class, supported by the imperial or national state, is the Haitian Revolution of 1791 to 1804. Yet the historical interpretation of this event is itself highly problematic. It was an extraordinarily violent event, even by the standards of Atlantic rebellions involving slaves or indigenes. Laurent Dubois estimates that in 1802–03 alone 100,000 people died in Haiti, nearly four times as many people as died in the seven years of the American Revolution. It resulted in slavery ending forever in France’s richest colony, the birth of the first independent black colony in the Americas, but also, through Napoleon Bonaparte’s cession of most of France’s North American possessions in the Louisiana Purchase of 1804, provided the territorial means through which slavery in the United States was able to expand spatially through the first half of the nineteenth century. The violence that led to the creation of Haiti out of the plantation colony of Saint Domingue, however, crippled the economy of the new nation. It also established patterns of dictatorial behaviour exhibited by its first leaders, notably Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe, that have since echoed through Haitian history. Dessalines is the great hero in Haitian history, but he was also noticeably cruel and violent. His first act on taking control of the newly inde-pendent Haiti in 1804 was to order a mass killing of most of the French whites who remained in the republic – perhaps several thousand people. Dessalines presented the killings as self-defence and as revenge for past crimes committed by French planters against enslaved Haitians. He declared that ‘yes, we have paid back these true cannibals crime for crime, outrage for outrage’. The legacy of Haiti as an excessively violent place lives on: in Hollywood as the home of zombies and vodou and in its present-day ranking as one of the most ‘fragile states’ in the Western Hemisphere.17

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to suggest that acts of violent resistance by enslaved people were wrong, futile, or counterproductive. When enslaved people were violent, their violence demonstrated three things. First, it made clear to fellow enslaved people that at least a few slaves were so unhappy with their predicament that they were willing to show masters that accepting enslavement was not the same thing as welcoming it. Their violent rejection of aspects of slavery demonstrated that enslaved people rejected the idea promulgated by their masters that enslaved people were naturally suited to enslavement and happy in that condition. Slave resistance through violence happened at all stages of Atlantic slavery, perhaps most commonly on slave ships. David Richardson estimates that perhaps one in ten slave ships experienced an insurrection.18 A typical insurrection arose on a British slaving vessel, the Clare, in 1729, when the captives, ten leagues off the Gold Coast, ‘rose and making themselves Masters of the Gunpowder and Fire Arms’ forced the white crew into a longboat and took over control of the ship, eventually making landfall and escaping back into their homeland.19 Of course, it was hard to control violence so that it was directed only against whites. Slave ships were frequently scenes of horrific violence between captives deranged by the horror of their confinement in fetid, crowded underground quarters. Henry Smeathman, in a particularly vivid account of the appalling conditions that faced captives on crowded and smelly slave ships, detailed how in the 1770s on a trip to Antigua male captives tore each other apart through fighting, making sailors too afraid to venture into what they saw as a violent hell-hole.20

Second, violence committed by enslaved people demonstrated to opponents of slavery in metropolitan Europe and northern America the true realities of slavery, separate from the propaganda presented to them by proslavery advocates. Slave masters always insisted that enslaved people in the Americas were happy with enslavement and that Africans preferred being in the Americas to the barbarous lives they had left behind in an essentially mythical ‘Africa’. The proslavery his-torian Edward Long, for example, noted in response to questions about whether Africans preferred to live in Jamaica or Africa that he ‘once interrogated a Negro, who had lived several years in Jamaica, on this subject’. The man replied to Long that in Jamaica he had ‘food and clothing as much as he wanted, a good house and his family about him, but in Africa he would be destitute and helpless’.21 The vio-lence that Jamaican slaves repeatedly carried out despite the strong likelihood that slavery would lead to cruelly imposed punishment showed that Long was fooling himself (or, more likely, had been fooled by a slave who told his interrogator what he thought his questioner wanted to hear).

It demonstrated also that slavery was not a benevolent institution but was permeated in every aspect of its being by coercion – sometimes purposeful, sometimes random – and it indicated that slaves responded to constant violence by being violent themselves. Planters only managed enslaved people through frequent punishment. The Jamaican overseer, Thomas Thistlewood, learned the importance of using violence on his arrival in Jamaica in 1750. Three months after starting work as an overseer, Thistlewood gave ‘old Titus’ fifty lashes for helping a runaway and after he ‘confess’d to have satt and eat’ with the runaway slave ‘several times’ he gave him another hundred lashes for this ‘villainy’. In 1756 – the year of ‘Derby’s Dose’ – Thistlewood administered fifty-seven whippings to a population of around sixty male slaves, gagged another four without whipping, and put eleven in stocks overnight.22 Even in the last days of slavery in the British West Indies and after abolitionist pressure on planters to reduce the punishment meted out to slaves, the amount of punishment endured by slaves just in the course of living and working on plantations was excessive. In the South American colony of Berbice, in the year 1830 alone, out of a population of 20,645 enslaved people, 2,118 men and 1,406 women (3,524 individuals) were flogged, put in stocks, or otherwise disciplined.23 When enslaved people fought back against the violence that surrounded them, it highlighted less what they had done, but just how vital coercion was in securing any measure of slave obedience.

Third, violence by slaves provoked sufficient outrage among abolitionists imbued with Christian doctrines, in which the iconography of Christ’s martyrdom was central, that they easily equated suffering slaves with their own suffering saviour. It is important to note that this equation occurred before enslaved people – at least in the French, British, and Dutch Atlantic worlds – had themselves become Christian. Slavery was not in itself problematic for Christians – believers, after all, described themselves as ‘slaves of Christ’. But what Katherine Gerbner calls ‘Christian slavery’ placed on slave owners a duty to act towards slaves as good Christians, an invocation that presumed masters would not exercise unreasonable violence against their slaves. Quakers – not until the mid eighteenth century notable as abolitionists – played a crucial role in insisting that violence towards slaves went against God’s will. Richard Pinder, a Quaker in Barbados, wrote a pamphlet in 1660 reminding slave owners that slaves ‘are of the same Blood and Mould, you are of’ and that if they ‘rul[ed] in such Tyranny over your Negroes … you will bring Blood upon you and the cry of their blood shall enter into the eares of the Lord of the Sabbath’. Pinder was an early ameliorationist, wanting to reform slavery along Christian lines. Quaker insistence that masters could not exercise unfettered dominion, including violence, over their enslaved property was one reason why they became a persecuted sect in Barbados.24

The violence of the slave system and the slave trade was commonly seen by its opponents through a Christian lens. The eighteenth-century slave ship captain John Newton, who became, as well as the author of the enduring hymn ‘Amazing Grace’, an early abolitionist, explicitly shaped his lengthy reminiscences about the brutality of the slave trade within an insistent Christian discourse of attaining salvation through grace so that previous sins could be forgiven. Other abolitionists, including black abolitionists such as Oladuah Equiano, whose account of the horrors of the slave trade remains one of the few texts to describe in detail the systematic violence of the Middle Passage, also adopted the language of religious conversion to describe what slavery and the slave trade was like and to suggest that the way out of this violence for masters and slaves alike was through accepting Christian doctrines.25

What made slavery a sin was its violence, as many early abolitionists attested. Granville Sharp, for example, came to abolitionism mainly through seeing West Indian planters in London treating their enslaved property with extreme violence. Thomas Clarkson, James Ramsay, and Anthony Benezet were all early abolitionists who first decried the violence inherent in slavery before coming to see the slave trade and slavery itself as inherently immoral and sinful.26 When evangelical Christians learned of slave rebellions and the grisly ways in which slave rebels were put to death, as in the well-publicized aftermath of Tacky’s Revolt in 1761, they tended to see African rebels as Christian martyrs. Vincent Brown notes that ‘news of the executions circulated amid prevailing sentimentalism and popular Christian martyrology, which helped the British to envisage their nation as a moral community founded in persecution, death and religious virtue’.27

As enslaved persons became Christian in the early nineteenth century, this language of martyrdom became ever more prevalent. The most famous Christian-inflected account of the travails that enslaved people put up with from evil and violent masters was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s bestselling Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). In this novel, Stowe draws on stories of slave resistance from real-life fugitives to paint a vivid, if problematically racialist, abolitionist portrait of an American South suffused with violence. The eponymous hero is a Christ-like figure ennobled by his suffering, an enduring figure of black victimization and stoic resistance through non-violence. Although abolitionists welcomed the attention that Stowe’s novel received, some were critical of the submissive quality of Uncle Tom. William Lloyd Garrison, for example, asked ‘is there one law of submission and non-resistance for the black man and another of rebellion and conflict for the white man?’ Thomas Wentworth Higginson lamented that Tom was not a hero who resisted more and suffered less.28 But what Stowe recognized was that, among a sentimentally inclined readership, tales of excessive violence, patient suffering, and implied redemption worked better than any other narrative strategy to inculcate sympathy among otherwise indifferent whites for the plight of enslaved blacks. Stowe wrote fully in the tradition of the first English-speaking abolitionist writers, like Thomas Day and John Bicknell. Day and Bicknell’s famous poem, Dying Negro (1773), was about an enslaved man who commits suicide rather than be transported into Caribbean enslavement, thus glorifying the African who chooses Christian redemption in death over servitude in life. As Celeste-Marie Bernier has argued, while white readers could easily identify with slaves as passive victims, they found it much harder to connect to black men praised as heroes, especially if, like Toussaint Louverture, or Frederick Douglass, they were unafraid to use violence in resisting enslavement.29 To some extent, that is a problem that has continued to the present.

Planters tended to either deny that the slave system was inherently violent or else insist that violence was necessary because otherwise naturally savage Africans would rise and kill them. The latter argument was prominent in the period when few Europeans challenged the idea that slavery was essential to produce luxury products that Europeans craved, such as tobacco and sugar, and when the morality of the enslavement of Africans was seldom challenged. In the seventeenth century, few planters in the Atlantic world bothered to try and explain why they were as cruel as they were towards enslaved people. If any explanation was given, it was that masters had to use violence against slaves because, as the English traveller Richard Ligon declared in 1650, Africans were ‘a bloody people’ and would – if not kept under strict control – ‘commit some horrid massacre upon the Christian population, thereby to enfranchise themselves and become masters of the island’. Ligon’s fears were realized in plots discovered in 1659, 1675, 1686, and most seriously in 1692. In that year, according to testimony later gained under torture from a slave named Ben, slaves conspired in an elaborate plan in which enough slaves to form four regiments would attack whites and seize white women, ‘to make wives of the handsomest, whores, cooks, and chambermaids of the others’. The Barbadian response was ferocious – after torture and court-martial, slaves were executed, castrated, and otherwise punished. The discovery of the plot did not inspire any reflection on the violence of the system. Instead, as contemporaneously in Jamaica, which experienced several small revolts resulting in the murder of several whites in 1678 and through the 1690s, the main thought was to punish rebels in as exemplary a fashion as possible. Hans Sloane described the series of brutal punishments used in 1688 – burning by a slow fire, castration, limb amputation, and whipping. Sloane elaborated: ‘after they are whipped till they are raw, some put on their skins Pepper and salt to make them smart’. The punishments were ‘harsh’ but Sloane thought that the slaves’ crimes meant they deserved what they got and that gruesome punishment was ‘sometimes merited by the blacks, who are a very perverse generation of people’.30

By the early eighteenth century, planters became more conscious that metropolitan Europeans found their behaviour intolerable – Charles Leslie, for example, wrote in 1740 of Jamaica that ‘no Country exceeds them in a barbarous Treatment of Slaves, or in the cruel Methods they put them to death’.31 In the French and British Atlantic worlds, the eighteenth-century plantation system was more successful and probably more violent than what had gone before.32 Some became concerned that ruling by violence alone was insufficient to control angry and violent enslaved property. One important thinker who believed that the punishment of slaves needed to be accompanied by promises of good treatment and mercy was Daniel Defoe, who wrote extensively on slave punishment despite never having visited any American slave plantation. Although he accepted that Africans were naturally vicious and could only be ruled with a ‘rod of iron’, as they naturally took advantage of anyone who tried to treat them well, Defoe advocated that the usual terror exercised against enslaved people be tempered by mercy so that masters would be able to inculcate among their slaves a feeling of gratitude that punishments were rational and intended to reform the slave. As George Boulukos argues regarding Defoe’s 1722 novel Colonel Jack, ‘he narrates what could be called the invention of slave-owner paternalism, the moment in which a policy of unashamed cruelty is abandoned from the suspicion that gentler ways might produce more efficacious results’.33

In most places in the Atlantic world, slave owners did not move far from the formulation begun by Defoe in the 1720s whereby it was assumed that slavery was inherently violent because Africans could not be controlled otherwise. Some writers tried to fool metropolitan observers by claiming that slavery was mostly benign and the relationship between slaves and masters was harmonious. Edward Long, for example, unconvincingly tried to counter Charles Leslie’s negative view of Jamaican planters by stating that Creole Jamaicans were ‘humane and indulgent masters’.34 But the evidence of planter cruelty and indifference to slave welfare was so glaringly apparent that few Jamaican planters were willing to corroborate Long’s fantasy. The violence of the plantation, as seen in the ubiquitous use of the whip, was accompanied by vast indifference to the living standards of enslaved people. The most extreme slave societies on the eve of the American Revolution – Jamaica and Saint Domingue – were probably the most unequal societies on earth, where enslaved people had a standard of living that even in good times barely kept them above subsistence and in bad times led to starvation and death.35 In the nineteenth century, the booming economy of Cuba assumed the mantle of most unequal society once held by Jamaica and Saint Domingue.36

Planters in these slave societies – societies which consumed enslaved people and in which violence and the threat of violence was neither hidden nor denied – accepted the reality that enslaved people hated them and that they could only get these adversaries to work and to not kill them through various forms of coercion, forms that changed and became subtler over time, but which remained forms of coercion throughout. Jamaica’s wealthiest early nineteenth-century planter, Simon Taylor, for example, was a successful planter because he refused to overwork his slaves, but he was far from being a ‘kind’ master. He knew that he depended on the slave trade and was distraught when Britain abolished that trade in 1807. He did not punish slaves directly himself but hired overseers who he knew would treat enslaved people firmly, ignoring any claim from enslaved people that they were punished excessively and that they experienced significant degrees of sexual violence from rapacious whites. As Christer Petley notes, ‘he was part of an ever-vigilant white minority, alert to signs of unrest among the slaves on his properties – people who had every reason to want to rise up, to free themselves and to harm or kill their oppressors in the process’.37

In the new United States, however, different demographic conditions shaped approaches to slavery. In particular, a majority white population in the slave states and a black population that grew after the mid eighteenth century from natural population increase (meaning that, after 1800, increasingly few enslaved persons had been born in Africa) encouraged planters to formulate proslavery ideologies predicated on the idea that slavery was upheld not by violence but by a shared understanding of reciprocity between paternalistic masters and mistresses and grateful, obedient, and protected enslaved people. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene Genovese have explored the dimensions of this idealistic (and unrealistic) ideology, which they term ‘slavery in the abstract’. They conclude that white southerners adopted an ideology of generous paternalism based on personal intimacy between slave owner and slave, where racially superior whites supported – often, planters believed, against their better interests – racially inferior subordinates whose natural place was at the bottom of the social order. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney II of South Carolina, for example, declared in the early nineteenth century that ‘Beyond mere animal suffering the slave has nothing to dread. His family is provided in food, shelter and raiment, whether he live and die.’ The way that proslavery white southerners described it, slavery was a pleasant condition much better than a freedom that enslaved people were unprepared for, and preferable to the uncertainty, drudgery, and exposure to dearth that they believed was the condition poor white people in the antebellum North daily experienced.38

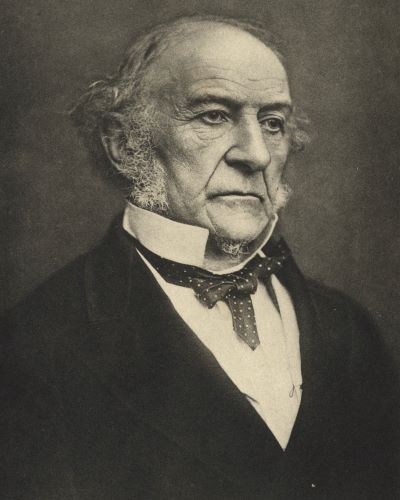

Similar views about slavery as a beneficent, non-violent institution were expressed by planters in other nineteenth-century slave societies. Their views percolated down into how free people of colour were treated after emancipation. Sir John Gladstone, Britain’s largest slave owner in nineteenth-century Demerara and a pioneer in a second variation on the slave trade, the importation of indentured labour from Asia into the eastern Caribbean from the late 1840s, was a firm supporter of gradual emancipation – so gradual, indeed, that it was unlikely ever to happen. Ameliorative measures, especially government restraint on what he considered to be inevitable misuses of power by violent masters, ‘cannot fail to effect such a progressive change in the general character and habits of the slave population that when the distant period should arrive the transition from slavery to freedom will finally be accomplished without revulsion or danger’. The key word is ‘distant’. His famous son, William, agreed with his father; as British Prime Minister, William Gladstone regretted that British emancipation had been precipitate, as people of African descent had to be kept in subjection, if not in slavery, because ‘in the case of negro slavery … it was the case of a race of higher capacities ruling over a race of lower capacities’.39 When ex-slaveholders had power over ex-slaves, as in the Jim Crow American South, they implemented such beliefs in new forms of coercion, such as convict-leasing, and in pernicious forms of violence dressed up as social control, such as lynching, which exploded in the American South after 1890.40 Freedom did not necessarily mean the end of racially motivated violence nor signified that whites were willing to allow ex-slaves and their descendants a place in the polities that emerged out of slavery.

That planters fooled themselves that slavery was not based on violence should not dismiss the essential truth that slavery did in fact improve, or at least become less obviously based on violence, over time. Such a statement does not absolve nineteenth-century slaveholders from their crimes against enslaved people. Violence was everywhere in nineteenth-century slavery. But slavery was more violent before 1800 than it was after that date – the Christianization of slaves, the influence of ideas of freedom and human rights, and the example of Haiti as what happened when societies gave in completely to treating people as disposable commodities all made a difference. Lessening violence was most obvious in North America, as the stark code of patriarchalism changed from the late eighteenth century into the less austere ideology of paternalism. As Philip Morgan explains, ‘patriarchal masters stressed order, authority, unswerving obedience and were quick to resort to violence when their authority was questioned … [while paternalist masters] were more inclined to stress their solicitude, their generous treatment of their dependents’. Moreover, patriarchalists – men like Simon Taylor of Jamaica – had no illusions that their slaves loved them, as did paternalists. They knew very well that their slaves hated them, that they were capable of rebellions, and that they had to be considered dangerous aliens, ‘domestic enemies’, to be controlled principally by violence and force.41 It was patriarchalists who were clear-sighted: slaves on nineteenth-century Louisiana or Cuban sugar plantations would have scoffed at suggestions that they lived under a mild form of paternalistic enslavement in which violence was replaced by kindness.42 But the paternalist vision of indulgent masters had considerable force. This is one reason why Harriet Beecher Stowe balanced her evil and cruel Simon Legree character, tormenting Uncle Tom, with the kind and benevolent but weak Augustine St Clare, who exemplified the benevolent aristocratic paternalist slave master.

This discussion leads us into the question of whether slavery in the Americas was more or less violent over time. In many ways, even asking such a question is not helpful in trying to understand the effects of enslavement on individuals. After all, it can be argued that it is misguided to try and quantify levels of violence in slavery and the slave trade, as violence is relational to individuals and psychological violence may be as devastating to the psyche as physical violence, as Nell Painter reminds us.43 But, bearing in mind this important caveat, if mortality rates can stand in as proxies for the violence of slavery, then the violence of slavery lessened over time. In the most violent part of the Atlantic slave system, the Middle Passage, mortality rates declined from a mortality rate of 22.6 percent for slave ships sailing before 1700 to 9.6 percent between 1801 and 1820. Although the slave trade was far from finished in the nineteenth century, with millions transported to Iberian America until the mid 1860s, the abolition of the slave trade by most major European slave-trading powers in the first two decades of the nineteenth century meant that fewer Africans suffered from the excessive violence of that trade than in the eighteenth century.44 And mortality rates also declined on slave plantations, even in major sugar producing societies. In the British Caribbean, annual mortality rates in Barbados declined from 5.8 percent in the mid seventeenth century to 0.8 percent in the late eighteenth century and to positive increase in the early nineteenth century. In Jamaica, there was a similar decline from 4.6 percent in the seventeenth century to 2.6 percent in the last quarter of the eighteenth century.45 It seems that the true nadir of slavery, when slaves suffered most from endemic violence, was when plantations were being formed and when the large integrated plantation was becoming established in the early eighteenth century. Ira Berlin, who introduced the idea of a ‘plantation revolution’ in French and British America around 1700, notes that after that date ‘Chesapeake slaves faced the pillory, the whipping post and gallows far more frequently and in far larger numbers than ever before’. The Chesapeake was following the example of Barbados half a century earlier. Antoine Biet, who visited Barbados in 1654, was shocked at planter sadism towards slaves, such as a master cutting off a slave’s ear, roasting it, and forcing the slave to eat it. He lamented that ‘it is inhuman to treat [slaves] with so much harshness’, a view echoed a year later by Isaac Birkenhead who claimed that planters were happy to kill their slaves, ‘dogs and they being of one ranke with each other’.46

Planters who were honest with themselves recognized that this violence turned their societies into Hobbesian ones. This relied on the common view of Hobbes as describing social order as based on blind obedience to Leviathan – state-sanctioned control over mechanisms of violence – without considering Hobbes’s careful theory of how such obedience was in the end based on consent (slaves never consented to their condition, so a slave society could never quite accord to Hobbesian principles).47 The Jamaican historian Bryan Edwards took this Hobbesian view of the proper relationship between masters and slaves when he argued that ‘the leading principle on which government is supported is fear, or a sense of that absolute coercive necessity, which leaving no choice of action, supersedes all sense of right’.48

A final case illustrates the centrality of violence to shaping the nature of slave societies and affecting every aspect of enslaved persons’ lives. Nicolas Lejeune, a psychopathic Saint Domingue planter, whose excessive cruelty to enslaved women was so outrageous that it led the French state to take the rare decision to prosecute a white man for violence done to black women, described the basis of planter power over slaves in the baldest fashion. In a 1788 speech made after his inevitable acquittal by a white jury on charges of cruelty and murder, Lejeune explained why in a complete slave society like late eighteenth-century Saint Domingue slave owners needed to be given a torturer’s charter. White rule, Lejeune insisted, was dependent on terror and the willingness of whites to use violence to keep slaves from ‘buy[ing] their freedom with the blood of their masters’. ‘The unhappy condition of the Negro leads him’, he argued, ‘to naturally detest us. It is only force and violence that restrains him.’ He concluded that ‘it is not the fear and equity of the law that forbids the slave from stabbing his master, it is the consciousness of absolute power that he has over his person. Remove that bit, he will dare everything.’49 Three years after Lejeune’s speech, his ‘daring negroes’ removed that bit by force and started, as Lejeune feared, stabbing their masters, taking by force what masters maintained only through violence.

Endnotes

- W. Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Harvard, 2013), pp. 9, 172, 191.

- E. E. Baptist, ‘Toward a Political Economy of Slave Labor: Hands, Whipping Machines and Modern Power’, in S. Beckert and S. Rockman (eds), Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development (Philadelphia, 2016), pp. 56–8.

- See P. D. Morgan’s review of Johnson, River of Dark Dreams, in American Historical Review, 119:2 (2014), pp. 462–4.

- See D. B. Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (New York, 2006) and P. D. Curtin, The Rise and Fall of the Plantation Complex: Essays in Atlantic History (New York, 1990).

- J. F. Stanfield, Observations on a Guinea Voyage, in a Series of Letters Addressed to the Rev. Thomas Clarkson (London, 1788).

- D. Tomich, Slavery and Historical Capitalism during the Nineteenth Century (Lanham, MD, 2018), p. ix.

- For the wider context, see D. Eltis and S. L. Engerman (eds), The Cambridge World History of Slavery, vol. 3, AD 1420–1804 (Cambridge, 2011) and D. Eltis, S. L. Engerman, S. Drescher, and D. Richardson (eds), The Cambridge World History of Slavery, vol. 4, AD 1804–2016 (Cambridge, 2017).

- D. A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York, 2008).

- T. Snyder, The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in British North America (Chicago, 2015).

- K. Halttunen, ‘Humanitarianism and the Pornography of Pain in Anglo-American Culture’, American Historical Review, 100:2 (1995); Z. Trodd, ‘Am I Still Not a Man and a Brother? Protest Memory in Contemporary Antislavery Visual Culture’, Slavery & Abolition, 34:2 (2013).

- T. Burnard, Mastery, Tyranny and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and his Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World (Chapel Hill, NC, 2004).

- J. Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting : Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (New York, 2014); M. Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven, CT, 2016).

- T. Clarkson, Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (London, 1786), p. 99; J. Walvin, The Zong : A Massacre, the Law and the End of Slavery (New Haven, CT, 2011).

- E. Rugemer, ‘Slave Rebels and Abolitionists: The Black Atlantic and the Coming of the Civil War’, Journal of the Civil War Era, 2:2 (2012); S. Drescher, ‘Emperor of the World: British Abolitionism and Imperialism’, in D. R . Peterson (ed.), Abolitionism and Imperialism in Britain, Africa and the Atlantic (Athens, OH, 2010); C. Hall, Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination 1830–1867 (London, 2002); P. Mandler, ‘“Race” and “Nation” in Mid-Victorian Thought’, in S. Collini et al. (eds), History, Religion, Culture: British Intellectual History 1750–1950 (Cambridge, 2000).

- V. Brown, The Reaper’s Garden: Death and Power in the World of Atlantic Slavery (Cambridge, MA, 2008).

- M. Kars, ‘Dodging Rebellion: Politics and Gender in the Berbice Slave Uprising of 1763’, American Historical Review, 121:1 (2016).

- L. Dubois, Haiti: The Aftershocks of History (New York, 2012), pp. 15, 42, 297–8; https://fragilestatesindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/951181805-Fragile-States-Index-Annual-Report-2018.pdf (accessed 10 Mar. 2020).

- D. Richardson, ‘Shipboard Revolts, African Authority and the Atlantic Slave Trade’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 58:1 (2001).

- M. Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History (London, 2007), p. 298.

- D. Coleman, Henry Smeathman, the Flycatcher: Natural History, Slavery and Empire in the Late Eighteenth Century (Liverpool, 2018).

- E. Long, The History of Jamaica: Reflections on its Situation, Settlements, Inhabitants, Climate, Products, Commerce, Laws and Government (3 vols, London, 1774), II, pp. 399–400.

- Burnard, Mastery, Tyranny and Desire, p. 104.

- R . Browne, Surviving Slavery in the British Caribbean (Philadelphia, 2017), pp. 196–203.

- K. Gerbner, Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World (Philadelphia, 2018), pp. 50–2.

- Rediker, Slave Ship, pp. 161–2; V. Carretta, Equiano the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man (Athens, GA, 2005).

- C. L. Brown, Moral Capital: The Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill, NC, 2006); M.-J. Rossignol and B. Van Ruymbeke (eds), The Atlantic World of Anthony Benezet (1713–1784): From French Reformation to North American Quaker Antislavery Activism (Leiden, 2017).

- Brown, Reaper’s Garden, p. 154.

- Sinha, Slave’s Cause, p. 443; D. S. Reynolds, Mightier than the Sword: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Battle for America (New York, 2011).

- B. Carey, British Abolitionism and the Rhetoric of Sensibility: Writing , Sentiment and Slavery (Basingstoke, 2005); C.-M. Bernier, Characters of Blood: Black Heroism in the Transatlantic Imagination (Charlottesville, VA, 2012).

- S. Amussen, Caribbean Exchanges: Slavery and the Transformation of English Society, 1640–1700 (Chapel Hill, NC, 2007), pp. 159–72; S. Newman, Free and Bound Labor in the British Atlantic World: Black and White Workers and the Development of Plantation Slavery (Philadelphia, 2013).

- [C. Leslie], A New and Exact Account of Jamaica (Edinburgh, 1740), p. 41.

- T. Burnard and J. Garrigus, The Plantation Machine: Atlantic Capitalism in French Saint-Domingue and British Jamaica (Philadelphia, 2016).

- G. Boulukos, The Grateful Slave: The Emergence of Race in Eighteenth-Century British and American Culture (Cambridge, 2008), p. 82.

- Long, History of Jamaica, II, p. 262.

- T. Burnard, L. Panza, and J. Williamson, ‘Living Costs, Real Incomes and Inequality in Colonial Jamaica’, Explorations in Economic History, 71 (2019).

- M. Barcia, Seeds of Insurrection, Domination and Resistance on Western Cuban Plantations, 1808–1848 (Baton Rouge, LA, 2008).

- C. Petley, White Fury: A Jamaican Slaveholder and the Age of Revolution (Oxford, 2018), pp. 48–51.

- T. Burnard, ‘The Planter Class’, in G. Heuman and T. Burnard (eds), The Routledge History of Slavery (London, 2011), p. 198; E. Genovese and D. Ambrose, ‘Masters’, in R . L. Paquette and M. M. Smith (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas (Oxford, 2010).

- T. Burnard and K. Candlin, ‘Sir John Gladstone and the Debate over Amelioration in the British West Indies in the 1820s’, Journal of British Studies, 57:4 (2018).

- W. F. Brundage, Civilizing Torture: An American Tradition (Cambridge, MA, 2018), chaps 3 and 4.

- P. D. Morgan, ‘Three Planters and their Slaves: Perspectives on Slavery in Virginia, South Carolina and Jamaica, 1750–1790’, in W. D. Jordan and S. l. Skemp (eds), Race and Family in the Colonial South (Jackson, MS, 1987).

- R. Follett, The Sugar Masters: Planters and Slaves in Louisiana’s Cane World, 1820–1860 (Baton Rouge, LA, 2005); M. D. Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion in Cuba and the Struggle against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill, NC, 2006).

- N. I. Painter, Southern History Across the Color Line (Chapel Hill, NC, 2002), chap. 1; S. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford, 1997).

- D. Eltis and D. Richardson (eds), Extending the Frontiers: Essays on the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database (New Haven, CT, 2008).

- P. D. Morgan, ‘Slavery in the British Caribbean’, in Eltis and Engerman, Cambridge World History of Slavery, vol. 3, p. 384.

- I. Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in America (Cambridge, MA, 1998), pp. 115–16; T. Burnard, Planters, Merchants and Slaves: Plantation Societies in British America, 1650–1820 (Chicago, 2015), p. 58.

- M. Nyquist, Arbitrary Rule: Slavery, Tyranny and the Power of Life and Death (Chicago, 2013), pp. 269–79.

- B. Edwards, The History, Civil and Commercial of the British Colonies in the West Indies (4 vols, London, 1794–1801), III, pp. 12–13.

- Burnard, Mastery, Tyranny and Desire, p. 137.

Chapter 11 (201-217) from A Global History of Early Modern Violence, edited by Erica Charters, Marie Houllemare, and Peter H. Wilson (Manchester University Press, 09.01.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.