Examining his work as the librarian of the two most important 17th-century Roman collections.

By Dr. Peter Rietbergen

Emeritus Professor

Radboud Institute for Culture and History

University of Radboud

Introduction

Seventeenth-century Rome was the actual or spiritual home of many learned men who, through the sheer bulk of their correspondence, the vast extent of their erudite contacts, the weightiness of the many tomesthey have left—published or still in manuscript—remain essentially unstudied and thus actually elude our understanding of the Respublica Litteraria, of the world of the Virtuosi, though, of course, the mere mention of their names may well elicit an ‘oh, yes’ from the listener and reader.

I refer to such men as Leone Allacci (1586–1669), the Greek-born Byzantinist, physician, theologian and librarian, and to Nicholas Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580–1637), the Provençal numismatist, botanist, historian, orientalist, and generally, ‘collectioneur’. I also refer to the German-born Lucas Holste, often referred to as Holstenius, whose importance for the intellectual life of papal Rome is generally acknowledged and constantly underlined. Yet he was a man, paradoxically, of whose political activities we are quite well informed,1 though we know far less about the actual extent of his cultural significance. The fact that Holstenius’ letters remain largely unpublished2 has been rightly lamented but little has been done to remedy it.

Using this rich source,3 this article proposes to analyse Holste’s role as an instrument of papal cultural policy through an outline of his main activities as a scholar and his work as the librarian of the two most important 17th-century Roman collections, the Barberini and Vatican Libraries; for both as an erudite in his own right and through his professional activities he gained a central role in the culture of Baroque Rome, where he first arrived precisely in the period the Barberini began their rise to power. Indeed, though at various stages the German scholar became adviser to, and even trusted friend of other powerful persons, like Pope Alexander VII and Queen Christina of Sweden, the Barberini family and, more specifically, Pope Urban VIII and Cardinal Francesco, were to become and remain Holste’s most important patrons.

When Holste died, in 1661, he was buried in the church of the ‘German Nation’ in Rome, the venerable Sta. Maria dell’ Anima, whose ‘providor’ he had been for several times. His monument was paid forby his long-time friend and protector, Francesco Barberini. The medallion that forms the centre of the monument shows the two rivers that dominated his life, the Elbe, on whose banks he was born, and the Tiber, that bisected the town where he died. But certainly far more interesting are the three figures that fill the roundel: atop a pyramid, an allegorical female representing Sacred or Church History sits on the left hand, while her sister Geography reclines on the right. Both have one breast bared, the other covered. Obviously, one would have expected Religion, or the Church, to dominate the scene. However, crowning the group is Philosophy, carrying a Sun—a Barberinian and, also a Campanellian image. Both her breasts are bare, as if to suggest that the knowledge she imparts is the most complete. Should one read this as a posthumous reminder of the one great intellectual force in Holste’s life, neo-Platonist philosophy? If so, it would also show that Holste’s predilection still was shared by his patron Barberini, though the latter had not been able to allow the more extremely materialistic implications of certain neo-Platonist views to be openly aired by the learned men attached to the papal court, such as Tommaso Campanella and Galileo Galilei.4 However this may be, Barberini’s friendship, and admiration for Holste certainly appear from the epitaph he intended for the funeral monument: it is a long, carefully phrased Latin text, lauding every aspect of Holste’s rich career.5

The Early Years

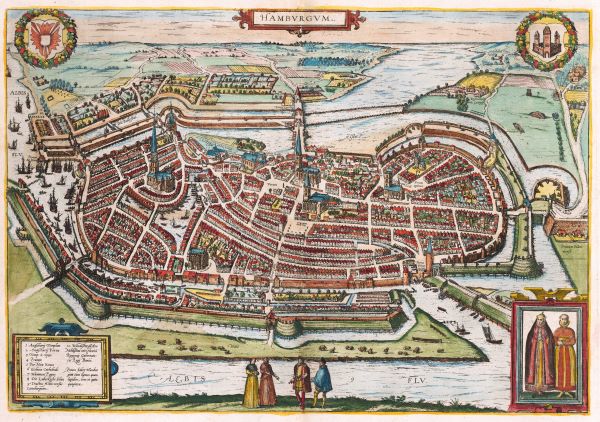

Lucas Holste6 was born in Hamburg on the 17th of September 1596, the seventh child of Peter Holste, the reasonably well-to-do owner of a cloth-dying business, and Maria Schillings;7 through his godparents, he was linked to the Hamburg patriciate. Almost no ‘independent’ sources remain to inform us about his early years: autobiographical notes, written at the end of his life, give us an impression of his youth, but through a lens obviously clouded by hindsight, and by the understandable need to present his entire life in a logical perspective.

His father first had him taught at home but at the age of five sent him to school. When young Holste reached his fourteenth year, he became the governor of the son of a wealthy Hamburg physician, Niko-laus Tadman. The next year, he was sent to the academy at Rostock but soon left again, deciding never to attend a German academy anymore because of the ‘barbaric’ culture of the school—a verdict smacking more of the topos usually attached to universities rather than, probably, reflecting the reality of his experience.

Holste’s father must have done reasonably well, for in 1615 or 1616 he could afford to send his son to the recently founded university of Leyden, in the Protestant Northern Netherlands—chosen, perhaps as much for the commercial contacts between the merchant metropolis on the Elbe and the new mercantile Republic of the United Provinces as for religious reasons.8 Thus, Holste left Hamburg, travelling to Holland with his older friend Gebhard Elmenhorst, a man of great philosophical learning and an acute sense of the need for an irenic stance in a society torn by religious dispute.

In Leyden, Holste’s keen intelligence and his growing erudition earned him the friendship of such scholars-teachers as Philip Cluverius ,Daniel Heinsius and Johannes Meursius. Aided by a scholarship from Leyden University, in 1618 he was able to accompany Cluverius, with whom he studied Greek, on a research trip to Italy, traversing the peninsula afoot, even journeying as far as Sicily9—not normally one of the stops on a Peregrinatio Academica.

After nearly two years, Holste returned to Leyden, to start earning a living as tutor to various young men, while he lodged with the professor of philology, Gilbert Jacchaeus. By now, for the first time he felt attracted to the ideas and ideals of St. Augustine, and contemplated conversion to Roman Catholicism.10 The fierce strife between the liberal-minded followers of the irenic theologian Arminius, amongst whom Holste counted most of his friends, and the more puritan adherents of the zealot Gommarus, that not only disrupted religious life but threatened also to divide the body politic of the young republic, may well have turned Holste’s thoughts in this direction, the more so as the purge which occurred in the following years forced a number of his Dutch acquaintances to leave Leyden, or even the Netherlands. Yet while some of them converted to Catholicism themselves, he did not take this step, yet.

In 1620, the Dutch diplomat Caspar van Vosbergen, whom Holsteknew from his early years at Leyden, engaged him as his secretary; therefore, he went to live in The Hague and accompanied his newmaster on missions to Christian IV of Denmark and to the elector of Saxony. In 1621, two of his brothers joined him in Leyden and, together, they travelled to Holstenia. Some sources erroneously claim that after his return to Leyden he converted to Rome.11

In 1622, Holste crossed the North Sea to England, to study in the libraries of London and Oxford.12 His interest there was in classical geography, as he planned an edition of the minor Greek geographers—which was to become a lifelong project, remaining unfinished as did so many of his visions. He also collected scholarly data for his friends in Holland. After two years, in which he mastered the English tongue, he was engaged by an English nobleman to accompany him to Spain. The plan proved abortive, however, because Holste’s patron died en route, in Antwerp.

The next stage in Holste’s career was Paris, where he arrived in October, 1624, first securing a post as librarian to Henri de Mesmes, count of Avaux, president of the Paris Parlement. Soon, he became a respected member of the circle of the great scholars of the day: the royal librarian Nicolas Rigault, the Du Puy-brothers, Pierre and James—veritable ‘information brokers’ in the world of learning—, the wealthy and erudite ProvençalparlementierNicolas de Peiresc, who had visited England, too, and Gabriel Naudé, who not only wrote the pioneer treatise on librarianship (1627)—one wonders whether Holste read it—but was also to be the real founder and manager of Mazarin’s great library.13 In1626, Holste transferred to the house of a French bishop, Mons. De Souvray. Indeed, he was well received in the ‘best French houses’, and given various stipends. He also befriended the imperial resident in Paris, who brought his name to the emperor’s attention as a man who, while being well versed in the affairs of the German states and their religious problems, was a great scholar, too.

After he finally decided to convert to Catholicism in 1624, schooled in his new faith by the Jesuit Fathers Denis Petau (1583–1652) and Jacques Sirmond (1559–1651), both famous Latinists and theologians, Holste started looking for a more permanent job. His friends soon recommended him to one of their Italian correspondents, Francesco Barberini, newly-created cardinal and, more important, nephew of the newly-elected Pope Urban VIII.

The great wealth which always fell to a new papal-royal family, as well as the social customs and cultural norms of the day, practically demanded that the new nipote be a magnificent patron in his own right, that he form his personal court and, amongst other things, build up a library of his own. Consequently, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, looking for a scholar to add lustre to his clientele as well as help him with his library, asked Lucas Holste to leave Paris for the Urbs and become his secretary and librarian—significantly, the request arrived on the feast of the Annunciation. Holste’s entering Barberini’s entourage shows that the Cardinal was seriously heeding the anonymous advice given him when he was first called upon to be his uncle’s Cardinal-Padrone, viz. to create a court made up of famous scholars who would help him realize the propaganda policy which the papacy had to pursue.14

In the Service of the Barberini

In May 1627, Holste left for the Aeterna in the suite of the returning papal nuncio, Orazio Spada. He was to live in Rome to the end of his days. From the outset, he was well cared for by his employer, both materially and honourifically. One finds him styled as ‘gentil-huomo dell’ Eminentissimo Cardinale Barberino’,15 by which title he must have been known until his ordination in 1643.16 Through Barberini’s influence, he was first given some benefices in Northern Germany;17 amongst these were a prebend in Hamburg, granted him in 1629, and canonries in Cologne and Lübeck.18 When the Thirty Years’ War finally settled the preponderance of the Reformation in this area, Holste first obtained a canonry in the cathedral of Olmütz as well asa prebend in the collegiate church of Bressanone;19 later he became a canon of St. Peter’s itself, as well as a Clerk of the Sacred College.20 All these functions were, of course, sinecures, but they certainly were not unrewarding—they must have brought Holste a very comfortableincome of several hundred scudi, annually.

Soon, Holste’s reputation was well-established. His fame even came to the notice of that august body, the Lincean Academy, who counted both Pope Urban and his nephew amongst their members. During one of their sessions in the late 1620’s, the Linceans decided to elect Holste among their number as well, considering he was both an uncommonly gifted linguist and a great scholar of ancient geography:

Il sig. Luca Holstenio, Hamburghese, Germano, giovane di bonissimi costumi, che si tratta hora apresso il Sig. Cardinale Barberini, dottis-simo in tutte le lingue. Porta Greco e Latino e, oltre le altre scienze, è geografo tanto insigne che se n’haverà notabilissima restauratione diquesta dottrina con ogni antica erudizione. E persona di tanto studio che continuamente è nello scrutinio delle cose più recondite nelle librarie, e sempre con lavoro di perizia, in modo che se n’haveranno bellissime fatiche, particolarmente d’autori non più visti, quasi tutti illustri con mille annotazioni. A questo effetto ha viaggiato studiosamente per bonaparte dell’Europa.21

Undeniably, Holste’s actual job had its dull sides. He compiled numerous indices, which made accessible Cardinal Barberini’s growing collections—of coins, of miniatures—but also the holdings of legal books kept in the Quirinal Palace, and the texts produced by Roman and other printers on the basis of Barberini-manuscripts.22 Yet, far more interestingly, being the learned adviser of the new Padrone, with practically unlimited resources at his disposal, Holste started creating the great library that Barberini, a newcomer, proposed to build. In a way, it must have been rather easy, at least as far as the material side of acquisition was concerned, and always taking into account the fierce competition which characterised a courtly centre such as Rome, in this field as in others. Nevertheless it demanded much expertise, the knowledge of what to look for, and where. Although we do not yet know in detail how the process went, it is obvious that in the1620’s and 1630’s the Barberini Library rapidly grew, both in size and in the importance of its holdings.23 What we do know—or rather what my analysis of Holste’s letters has shown—is that Barberini, besides buying books, was especially eager to acquire precious manuscripts which in some way or another were of cultural, viz. archaeological, historical, philological, scientific, theological or philosophical value. To this end, Holste was sent on a number of research trips that brought him all over Italy.

Thus, while escorting the famous convert and later cardinal, Prince Friedrich von Hessen-Darmstadt, to Malta in 1637—an episode which should be studied in detail24 if only because Holste apparently advised the Grand Master on the improvement of the island’s function as a military bulwark against the Turks—he visited the libraries and manuscript collections of Naples, Messina and Palermo. In the collections of the Basilian Fathers in Messina, which he described as the only real treasure trove he encountered, he found one veritable diamond, a 14th-century manuscript world chronicle in Greek. Whether he was able to secure this gem for Barberini is not clear. However, returning from Malta, he spent several weeks in Naples to conduct some pretty shady deals with the Capuchins, in whose library he also had found much to his and his patron’s liking. It appears that, in view of Barberini’s power, the poor fathers were practically forced to simply part with the choicest items of their collection.25

The greatest surprise, however, was the marvellous library of Monte Cassino, which sent Holste into rapturous transports.26 There, he foundsome unknown works of Peter Diaconus, as well as papers relating to the Council of Chalcedon, that was of significance to Rome because of its claims concerning the papal position in the rift that, later, had occurred between the Latin and the Greek Churches. He asked Barberini to sent him some of his own books, that he might confront the status quaestionis with the new material. In doing so, he was able to correct a number of current scholarly opinions. He also discovered a series of martyrologia, amongst which those of Sts. Felicity and Perpetua, which enabled him to correct Cardinal Baronius’ famous martyrologium on some essential points. In this period, as well in later years, Holste was also gathering material about the lives of the popes, constantly adding to the known corpus of vitae although his findings were not always deemed lucky ones, perhaps because some of the facts tended to be iconoclastic. Most of this work, however, was not published till long after his death.27 Precisely to get a grip on the enormous amount of material he found in various Italian libraries, Holste spent considerable time in compiling indexes of their collections. Thus, he catalogued the holdings of the library of Monte Cassino, and, on another occasion, the Greek books in the library at Carpi.28

In the early months of 1638, Holste returned to Rome. Perhaps inconsequence of his trip, we find Pope Urban issuing a breve that, inthe same year, forbids the Neapolitan Franciscans to sell any books or manuscripts before having given first refusal to Francesco Barberini—apparently this collection, too, held items of interest to the Pope’s nephew.29 The trip must have been considered successful, for in 1641 Holste left on another journey of research and acquisition, this time roaming through ‘Etruria’—i.e. Tuscany. Among other things, he tried to trace some manuscripts on the life of Christ, written by Porphyrius—Holste had already published a book on this author’s life and works in 1630—but the dusty cupboards of the grand-ducal library in Florence did not yield the desired results.30

Meanwhile, though the Barberini Library must have gained considerably by Holste’s travels, it also grew by means peculiar to the power structure of early modern Rome. Thus, persons who, for some reason or other, sought Barberini’s favour—as the papal prime minister, he could arrange well nigh anything—did well to please him with the gift of a manuscript, often using Holste as an intermediary.31

In the meantime, Holste’s status in the world of learning had been rising steadily, both in Rome and in Europe at large. In the papal capital, the ever more magnificent courts of the various Barberini siblings, now partially transferred from the rather modest family place on the Via dei Gubbonari, bought by the Pope while still a cardinal, to the stupendous new building erected near Quattro Fontane, were the scene of a vigorous cultural and, more specifically, intellectual life.

Holste was a well-liked member of the Academy which Cardinal Francesco had founded in 1624—another decision which helped him to define his new position as the expected leader of Roman cultural life—and which now gathered in the beautiful nymphaeum of the new palace, with its splendid fountain,32 an academy that functioned in accordance with Barberini’s ideas about the role of Divine Wisdom on earth. Meanwhile, in the Basilian monastery in Rome, yet another academy convened regularly, under the aegis of a man who, like Holste, was a Barberini famigliare, the well-known scholar and musical theorist Giovanni Batista Doni (1594–1647). The members often discussed topics relating to one of Barberini’s, and Holste’s, main interests, the question of the differences and similarities between the Greek and Latin Churches.33

The Mind of the Man

It is not easy to ‘access’ Holste’s mind. Trying to distil an image of his innermost thoughts from the thousands of letters he wrote, from the introductions to his editions—printed and manuscript—one finds him elusive, still. Yet, there is one letter that seems to reveal as much as, perhaps, we will ever know about him, about the reasons for which he decided to convert to Catholicism, and about his deepest intellectual leanings. He dispatched it in July,1631, to his old patron and friend Peiresc, who, with his customary but in this case truly remarkable generosity had given him no less than 25 manuscripts, recently acquired,of a scientific-philosophical nature which Holste greatly coveted. Holste wrote:

I would like to testify, from the depth of my heart (…) that up till now no one ever has favoured me more and with a more welcome gift than you have, and to no one does my research owe as much as to you. For in your remarkable benevolence and almost overgenerous friendship you have given me access to the texts of those authors which I have tried to acquire without grudging myself the expense (…) in order to be able—devoting myself entirely to them—to read them for myself and to give them to the public. As a very young man, already, I was attracted to Platonist philosophy by the lecture of Maximos of Tyre, Chalcidius and Hierocles; I felt growing in me a fierce desire, first to know more, and then to use all my forces to bring such a divine way of philosophizing to mankind, and to promote it. The remarkable use to which I could put these studies, only has strengthened this effort. For seeing that Bessarion, Steuchos and others confirmed the teachings of Plato through their reading of the Fathers of the Church, I turned completely to those Latin and Greek texts that deal with this contemplative and mystic theology, which excites the soul to God. Consequently, I came to admire greatly the divine and true way of philosophizing of the Fathers. Almost unknowingly, I began to feel myself part of the Catholic Church again, an experience also felt by Saint Augustine, as he testifies in his Confessions. These divine contemplations really turned my mind to the knowledge of Truth, and confirmed it. From then on, I had a basis from which to act in my encounters with the nonsense and the petty arguments that usually move those who recently deal with the Faith.

Among the texts Holste received and began to annotate, in view of a subsequent edition, were several commentaries on Platonic writings, such as Proklos’s notes on Plato’s theology. Holste studied these texts, comparing them with other ones which he had copied during his stay in England or had acquired in Paris, among which the neo-Platonist text on physics by Michael Psellos, and with texts which he found and had copied either in the Vatican, or in the Barberini libraries. Favourites were Hermeias’s notes to the Phaedros, but Holste also was charmed by Jamblichos of Chalcis’s ‘Life and Works of Pythagoras’, a neo-Platonist interpretation with strong occult tendencies.

However, Holste did not realize his plans for the edition of various neo-Platonist texts. Precisely in the early 1630’s, the cultural climate in Rome changed rather dramatically. The liberal atmosphere that had characterized the early years of Urban’s pontificate disappeared, if only because such causes célèbres as the Campanella- and Galilei-cases, which both had neo-Platonist and, even more dangerous, materialist philosophical implications, seriously threatened the theological and hence political unity of the Counter-Reformation Church.34 Neither the Pope, nor his nephew Francesco, Holste’s patron, could afford to risk any scandals, whatever their private philosophical-theological opinions might once have been, or still were. Of course, it is all too easy to put this down to a mere desire to hold on to power at all costs on the part of the Curia. Nor would it be fair to accuse Holste of intellectual dishonesty, though, admittedly, he does not seem to have been the kind of courageous person who would be willing to endanger his career for the good cause of scholarship. Indeed, Holste may well have realized that the times—the Thirty Years’ War seemed to spell the final ruin of Rome’s supremacy, which was challenged on other fronts as well—asked for unity, rather than for an attitude that would open the Church of Rome to all kinds of accusations of accepting, or even fomenting heterodox ideas.

Yet, Holste continued, in his own way and, admittedly, not in the open, to voice his criticism of such bigotry as he often encountered. In 1633, he complained to Peiresc about the ignorance of some of the cardinals who sat on the Congregation of the Index, who judged which books were, and which were not to be read by the faithful, telling that he was so angered by some of the things they said that he had decided never to attend anymore. In the same letter, he tells about the judgement passed on Galilei:

Surely, nobody can see without indignation how Galilei’s book, and the entire body of Pythagoreic or Copernican knowledge is judged by men who have no idea of mathematics and of the course of the planets, and no interest in physics, precisely where the authority of the Church is at stake that will be seriously impaired by a wrong judgement. I urgently admonish them to realize that the oldest authors were mathematicians who, with remarkable fervour, devoted themselves to the cause of truth and that precisely those who in recent times have resurrected that knowledge in their scholarship have almost equalled the Ancients. Galilei has been brought down by the hate and jealousy of those who feel that only he stands in the way of their being viewed as the best mathematicians.

However, neither Holste’s strong opinion in this matter, nor the more daring for openly critical tone adopted by his friend Peiresc in a letter to Francesco Barberini, could move the Roman authorities.

Between North and South

For all its limitations, Holste flourished in the Roman milieu. His knowledge of North-European affairs was useful to Francesco Barberini in his quality as papal foreign secretary. In 1630, Holste was sent on missions to Poland, to negotiate with King Sigismund and bring the red hat to Monsignore Santacroce, the papal nuncio in Warsaw; he also went to Vienna, where Emperor Ferdinand asked him to oversee the reformation of the monastery of Augustinian canonesses attached to the Hofburg—the imperial family being greatly in favour of the new, observant movement of the Agostiniani Scalzi, the barefooted Augustinians, that had sprung up in the Order in the previous decades.35

Holste’s contacts in high places and his own position enabled him to be of help to many, and thus make a great number of friends. He was certainly a great support to all the ‘Germans’ who came to Rome, and, often carrying letters of recommendation, presented themselves to their most influential countryman at the papal court, as was, of course, quite normal for anyone who went on a trip, whether it was of an academic, cultural, diplomatic or religious nature. For them, and others, Holste secured audiences with the pope and the cardinals—for the highborn—or monetary help, for the lowlier ones.

More important, perhaps, was his ability to present his friends and acquaintances as candidates for the many jobs that were in the Curia’s giving—many letters written to him clearly show the gratitude of those who had thus been helped, or asked to be assisted in this way.36 Or, as one bishop, residing in a backwater cathedral town, put it: while being“lontano dai virtuosi” meant a kind of cultural exile, the “esser lontanodalla corte” meant that one was often denied promotion if no mighty intercessor was willing to lend a hand.37

In a more specific, professional way, Holste was often asked to use his position as librarian to enable scholars from all over Europe to pursue their research on the basis of Roman material. For example, people asked him to wield his influence to obtain permission to borrow manuscripts from the Barberiniana. Gronovius was helped in this way in 1641,38 and the Maronite priest and scholar, Abraham Ecchellen, while working in Paris on the Polyglot Bible, even managed to have books and manuscripts sent, there.39 Some people, however, were disappointed in their expectations, like Marin Mersenne, the famous mathematician from the Order of Minims, who in 1644 sought entrance to the Vatican Library and discovered not only that Holste could not help him, but also that he and other friends, like the learned Greek scholar Leone Allacci (1586–1669), who himself was attached to the “Vaticana”, had problems in circumventing the Cerberus-like restrictions imposed by the library’s current custos, the orientalist Horatio Giustiniani.40

Of course, the system worked both ways. Many persons regaled Holste with their unasked for manuscripts, hoping he might read them, and perhaps, in thus flattering him, hoping to secure his help in their publication.41 He often obliged.42

Being a scholar and living in a world which increasingly valued knowledge and scholarship not only as a sign of culture but also as a means of power, then as now meant living in a milieu characterized by professional jealousies, accusations of plagiarism, petty intrigues about jobs and positions, incriminations of stealing one another’s discoveries and ideas. Consequently, the correspondences of the 17th century resound with the clamour of battles fought and reputations vociferously destroyed. Holste, being prominent and successful, had his own opponents. Whether or not the criticism levelled against him was justified, is almost impossible to judge, now. Two episodes may serve to illustrate the situation.

In 1636 Holste’s character, ambitions and ways were analysed with great acuity in a letter written by Gabriel Naudé (1600–1653) to their mutual friend Peiresc, concentrating on Holste’s rivalry with Leone Allacci:

Le mal entendu d’entre luy (sc. Allacci) et Mr. Holstenius n’est pas dignede vous mettre en peine, d’autant qu’il est fort leger et presque imperceptible à ceux qui ne pénètrent pas dans l’interieur de tous les deux ensemble, car ils se parlent, voyent et entreservent mutuellement, et exeptécette jalousie que chacun a de vouloir prevenir son compagnon à publier ou se servir de certains manusripts qui leur viennent entre les mains, tout le reste va bien, quoy qu’à dire vray le seigneur Leone ne peut quasifaire autre chose, que ce qu’il fait en cette occasion. Car en effet Mr. Holstenius, comme il a une tres grande capacité, conçoit aussi de tresgrandes desseins, et le plus souvent bien differens les uns des autres, comme seroit, par exemple, d’imprimer tous les Geographes anciens, de recueillir aussi toutes les oeuvres semblables des Philosophes Platoniciens, de faire imprimer tous les Autheurs manuscripts et anciens qui ontescript de la vie des Papes, et autres semblables, lesquels comme ils sont de tres grande haleine, aussi ne les peut-il pas finir si promptement, veuqu’encore il y travaille avec assés de relasche. Cependant, comme il croittous jours d’accomplir ces desseins, aussi a-t-il déplaisir que quelqu’un entreprenne rien de ce qui on peut despendre; et, au contraire, le sr.Leone Allatio, qui est d’un naturel ardent et expeditif, se trouvant beaucoup de petits Autheurs qui concernent ces matières, se fasche de n’avoirpas la liberté d’en faire ce qu’il veut, et d’estre empesché par ces desseins qui ne se finissent jamais, de publier ce qui peut estre advantageux pour luy et pour le public, et d’exempter les siens qui sont tous prets, et n’attendent que la commodité des Imprimeurs.43

This quotation sketches, in a nutshell, some of Holste’s characteristics: his intelligence, his creativity, his ambition and his apparent inability to really finish the many over-ambitious projects he envisaged and started, all the time monopolizing precious manuscript sources other people liked to work on as well. It also sketches the grave problems of the 17th-century scholarly brotherhood, problems that certainly were not peculiar to Holste only. This community, in its widest sense the Respublica Litteraria, was rife with the negative characteristics common to any academic society. Like many others, Holste did not succeed in living up to the ideal image this ‘Republic’ had of itself, and that has been, consciously or unconsciously, perpetuated by its later chroniclers, well into the present century.44

Several years later, in 1644, Holste, while working on the edition and translation into Latin of Arrianus’s originally Greek treatise on hunting, De Venatione, decided to publish it in Paris. John van Vliet (1620–1666), a young Dutch scholar, was working on this text too—whether or not known to Holste is not altogether clear. The scholar Claude Sarrau,taking Van Vliet’s side—whether there was a side to take is unclear as well—wrote to his colleague André Rivet that the manuscript used by Holste had been ‘given’ to him by Saumaise, who ‘had’ it from the Palatine Library, at Heidelberg. However “cet ingrat n’en dit pas unmot; c’est ce qu’on apprend en Italie de s’approprier ce qu’appartient a autruy”.45 Should Holste not have edited the manuscript, because Saumaise might have wanted to do so, too? Should he have stopped working on it to enable Van Vliet to continue and complete his edition—which the Dutchman did anyhow? However this may be, from this episode the present-day editors of the Sarrau-Rivet letters construct a case of malice aforethought when they dwell on it again in another context: in 1645 Holste is reported to have published the letters of St. Ignatius, though, again, someone—this time, Isaac, the young, soon to be famous son of the famous classical scholar G.J. Vossius—was working on them. Sarrau wrote to his correspondent: “la fripon-nerie de Holstenius lui aura servi […] pour en diligenter l’impression”, and Rivet, a bit surprised, replies: “Je n’avoy pas sçeu qu’Holstenius eust voulu pocher l’ouvrage de Vossius”.46 Given the fact that Holstenever published an edition of these letters, the malicious effect of such unfounded gossip must be judged seriously indeed, but it was entirely characteristic of the atmosphere in the European scholarly community.

Printing and Power: The Barberini Press

In the context of the Barberini’s involvement in various forms of scholarly interaction, one particular Holstenian episode should not go unmentioned. During the year 1636 and the early months of 1637, before Holste left on his trip to Malta, Barberini asked his advice on a matter which the Cardinal had very much at heart: the quality of the presses operated by the papal government. However, a problem arises in identifying the precise printing office that was the object of Barberini’s main concern and criticism.

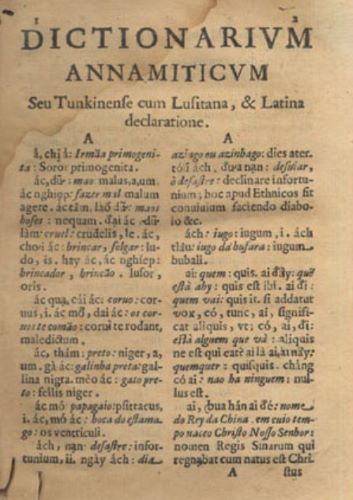

According to a short note by the 18th-century scholar who catalogued Holste’s papers, we are confronted with documents47 dealing with the affairs of the Typographia Polyglotta, the printing office of the Congregration de Propaganda Fide, the papal Ministry of Missionary Affairs.48 The press had been founded in 1626, as a logical corollary of the foundation of the Propaganda itself in 1622; for indeed, what better instrument for spreading the Faith than the printed word? After the quite considerable sum of 18,000 scudi had been invested in its equipment, the Polyglotta had in short time become worthy of its name, printing in some 23 languages, from Arabic to Chaldean and Syrian. However, as its products were not sold but distributed free of charge, financial troubles were inevitable.

In 1638, the influential and intelligent secretary of the Propaganda, Mgr. Francesco Ingoli, finally analysed the now acutely problematic situation; in veiled terms he accused the Apostolic Chamber, the papal Ministry of Finance, of niggardliness because it grudged the press its monthly allowance of one hundred scudi, pointedly referring to the Dutch East India Company, which according to him spent a fortune to aid the missionary activities of the heretical ministers of the Dutch Republic, and to the famous Greek and oriental presses operating in Holland. But was this the problem Barberini’s initiative sought to solve by establishing a new Press?

One thing is certain: in 1638, the Cardinal decided to establish a Latin and Greek Press in his official residence, the Palazzo della Cancellaria. Holste was to be its director, and hence was asked to prepare a memorandum on the costs of equipping and running such an enterprise.

Taking the Parisian ‘Imprimerie Royale’ as his example, Holste first set out to ascertain the availability of enough punches and matrices to enable the casting of a working collection of type. Besides the Propaganda’s own collection, there was the famous set of Greek type, formerly in the possession of the Salviati family, but which they had sold to Venice. However, in Spring 1637, one Herman Khircher and one Christofano, type founders, supplied the new Barberini Press with a sizeable collection of 957 type, both Latin and Greek, including some italic sets, at a price of 450,70 scudi.49 Other type seems to have been cast in the following months, requiring a total expenditure of 1800 scudi. Meanwhile, Holste wrote Barberini that the annual cost of running the Press would be some 400 scudi in equipment and salaries.

Strangely, we do not know what exactly happened next. Serious doubts about the actual viability of continuing the operations of the Typographia Polyglotta were officially voiced for the first time in the last months of 1637 and in 1638. It was then that Ingoli started his counter-attack, defending the Press’s singular importance. Yet, in the years that followed there were even thoughts of dismantling it. The crisis was only resolved in 1642, with the reorganized installation of the Press in the newly-built Propaganda-palace on Piazza di Spagna.

In view of all this, Barberini’s initiative to set up a new Greek and Latin Press does not seem to have been an adequate solution to the Polyglotta’s problems. Therefore, perhaps, the identification of the documents cited is mistaken. It seems reasonable to offer an alternative interpretation, for which some arguments are available.

From the letters exchanged between Holste and Peiresc as well as from letters written by Peiresc to Barberini, we know that in 1635 both the Cardinal and his librarian expressed their concern over the disorganized state of affairs at the Typographia Vaticana, the Vatican Library’s own Press,50 amongst other things lamenting the ugliness of its (Greek) type—Holste, perhaps, complaining on the basis of his experiences with his Porphyrius-edition. Peiresc agreed and in a long letter commented upon the possible remedies, suggesting a reorganisation along the lines of the Royal Press in Paris. He also expressed approval of a ‘plan’ of Barberini’s. Surely this must refer to the project of the Greek and Latin Press—were not these the most important languages represented in the Vatican’s own collection and used in its own publications? Thus we may, perhaps, decide that Barberini’s initiative was aimed at the improvement of the Typographia Vaticana, and that it served its aim, too.51

Favors Continued

With the death of Urban VIII in 1643, the influence of the Barberini temporarily waned, but though its source now fell dry, their much-criticized wealth remained virtually intact for another century. Francesco and his two brothers—the other Barberini cardinal and the prince of Palestrina—went on spending fortunes on whatever forms of patronage they favoured. The new pope, Innocent X Pamphilij, initially rather inimical of his predecessor’s family, soon came around—rumour had it that Holste was partly instrumental in this—and even helped them, and their clients, to retain their influence, only asking the hand of one of their daughters for his nephew—and, of course, a sizeable dowry to go with it.

Thus, while Holste continued to be a favourite at the court of Cardinal Francesco, he became persona grata, too, at the court of the new pope. And though Innocent never became a patron of the arts in the grand style of the Barberini, Holste’s scholarship was esteemed, as well as being considered of practical value to policy-making in the Curia.

For example, we find him an adviser to the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, concerned with all sorts of missionary matters both in Europe and overseas. In 1651, he composed a memorandum on the training of future missionaries, arguing over maps to be given to priests who ventured to other continents and discussing the difficult question of the Chinese Rites—concerning the ways especially the Jesuits had felt they should accommodate Christianity to Chinese customs. We also find him admonishing a German princess who, a convert herself, was sent back to her country to try and make some more proselytes in her family.52 It is clear Holste was considered an expert on matters of liturgy, too.53

The apotheosis of Holste’s professional career came in 1653, when he was promoted to the much-coveted, for highly prestigious, position of first custodian of the Vatican Library, succeeding Cosimo Ricciardi. Though the Vaticana, then as now, was nominally presided over by a cardinal-librarian—a function which, for its status, was usually reserved for one of the reigning pope’s nephews—the first custodian was the actual director of the greatest library in Rome, the keeper of one of the most important collections of books and manuscripts in the world. No wonder letters of congratulation started coming in from all over Europe, praising Holste for his virtù, that mixture of accomplishments, creativity, merits and learning which, according to his eulogists, made his nomination such a deserved one.54

Holste’s new position must have added greatly to his responsibilities, and he did not shirk them. The archives of the Vatican Library still contain the many memorials he composed and issued to ensure the proper gestation of this big organization, which had not been functioning at all well. Nevertheless, other tasks were to be his when, in 1655, Cardinal Fabio Chigi became Pope Alexander VII (1655–1667).

Holste and Alexander VII

From the outset, the new pontifex aimed at the restoration of Rome’s former, imperial grandeur, in all its aspects. Much was expected of him. One of Holste’s correspondents wrote, echoing sounds that had also been heard when Urban VIII ascended the throne: “speremo chele lettere, e dottrina, si rimetteranno in fiore per l’Italia con questo nuovo pontefice”.55 Nor was he alone in voicing this hope. Alexander did not disappoint those who felt that the Pamphilij pontificate had been a cultural desert. In fact, in many ways he continued where Pope Urban had left off. Restoration and new building activities changed the face of Rome, giving its centre its present Baroque aspect.56 Like Urban before him, Alexander, an educated and even scholarly man, not only wanted to make Rome the visual “caput mundi”, he also strove to remake it into the capital of the invisible, but nevertheless real and powerful world of learning, to ensure that the perilously diverging worlds of Christian doctrine and intellectual life would remain united, both bowing to the supreme authority of the Church, and that of the pope, as the mediator between Heavenly Wisdom and the Earth. To this end, Alexander spent much time, effort and money on the Roman university, the Sapienza,57 which first had been revitalized by Urban VIII, finishing the palace which housed it and creating a great library where there had been no books whatsoever—and, of course, then naming it Biblioteca Alessandrina58—and endowing new chairs as well as starting a botanical garden.

However, he also stimulated scholarship outside the university milieu as much as possible. The old Vatican Library, the new Sapienza-collection and the private library of the Chigi family, started, under Alexander’s aegis, by his nephew, the Cardinal-Padrone Flavio Chigi in unabashed emulation of the Biblioteca Barberiniana established by Francesco Barberini, were the obvious targets of his patronage. If only therefore, the learned and experienced keeper of the Vaticana who by now was considered one of Rome’s leading scholars, was a welcome collaborator.

So Holste’s star rose higher than ever before. The Pope consulted him on all kinds of matters which, somehow, related to his special expertise: the Oriental Churches, classical learning, library management, and other topics. Most of the often erudite inscriptions which, due to Alexander’s positive inscriptomania, adorn the buildings of papal Rome to this day—often vying for pride of place with the Barberini bees—, are the result of the collaboration between the Pope and his favourite German scholar. Usually, Alexander’s two preferred architects, Gianlorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona, informed him of the amount of space available on a façade or wall, and of the number of lines and letters it would take; the Pope then sent a little note to Holste, with his own ideas or a set of alternatives, asking for improvements or other suggestions.59

Meanwhile, Holste went on with is own research—always, or so I think, keeping an eye on the practical, even political side of his scholarly enterprises. Thus, in 1658, he published the work which today not only is considered his greatest discovery, but also his most important contribution to scholarship: the Liber Diurnus Romanorum Pontificum, a book of forms used in the papal chancery since the ninth century and which had shaped papal administrative practice for a very long period.60

Other honourable tasks fell to Holste as well. The much discussed removal of one of Italy’s most famous libraries, that of the former dukes of Urbino, to Rome, where its contents were divided between the new Alessandrina, the Chigiana and the Vaticana, was devised and supervised by him, among others.61

Perhaps his greatest honour was bestowed upon him in Autumn, 1655, when Pope Alexander named him his special legate, to travel to Innsbrück and there receive the profession of faith which the best-known convert of the 17th century, Queen Christina of Sweden, would swear in his hands. Obviously, Holste’s Northern European origins, his own status as a convert, his continuous dealings with other high-born neophytes and his international standing as a scholar were all considered qualities that would make him persona grata to the high-spirited and cultured virago from the Lutheran North, who was about to make her stormy descent upon the Catholic South.62 According to all accounts, the mission was a success.

Buyers and Sellers: Bookmen at Work

In the hurly-burly of this rich life, Holste had to fit his tasks as the keeper of, by now, two great libraries: the Vaticana and the Barberiniana. However, since his meeting with Christina proved to be the basis of a life-long friendship, he soon became involved with yet a third library: he was the ex-Queen’s natural adviser when, from 1659 onwards, she finally settled down and started her own considerable collection of books and manuscripts.63

Amidst all this bustle, Holste could not, of course, forget his first duty as Barberini’s librarian. Nor did he. Hunting for manuscripts, he never forgot that they, though certainly desirable both as precious objects in themselves and as important sources of knowledge and learning, were not the only elements which made up the library he was creating for the Cardinal. An extensive and representative collection of contemporary authors and their printed works in every field was what Barberini desired and what Holste, being a collector himself, strove after, too, though undoubtedly on a far more modest scale. Hence, it was one of Holste’s duties to be informed as comprehensively as possible about new publications both in Rome, in Italy and, indeed, from all over Europe.

Precisely because books were such an important element in papal propaganda—both as carriers of messages and as objects in themselves, to fill the libraries that then were consulted by scholars who would be beholden to their papal owners—it is important to understand howa librarian like Holste went about purchasing them. Yet, we do not know yet how this was actually managed, certainly not during the early period of Holste’s librarianship in Barberini’s service. Admittedly, in Holste’s own papers, letters from booksellers do survive, but they do not indicate a great volume of purchases.64 A thorough search of the gigantic Barberini Archives, which are now becoming accessible to the public through the dedicated cataloguing of the staff of the Vatican Library as well as other scholars, might eventually throw some light on this problem, but as yet we do not really understand the ‘system’.

Of course, Rome had many publishers and booksellers who must have been able to supply Barberini with just about every book printed in the various towns of Italy. However, for information about non-Italian titles, produced beyond the Alps, the Cardinal had to fall back on his own international correspondence and on the foreign friends of his librarian. Indeed, Holste’s learned acquaintances did, of course, serve this aim. Thus, we find him making notes of the recently-published titles mentioned in the letters Gabriel Naudé wrote to him and then, apparently, ordering them.65 Also, an Italian friend, the Venice-based bishop of Città Nuova, Giacomo Filippo Tomasini, had contacts with Europe’s greatest book market, the Frankfurt Fair, through a book-seller named Julius Weiseldeck,66 from which Holste profited as well.

Yet, an often irregular exchange of letters between scholars hardly could be the basis for a systematic acquisition policy for a huge library. To actually buy books, Barberini, or rather Holste could rely on the, often rather limited, stock of Italian booksellers, or, again, use their international relations. Another possibility was, of course, to order directly from the main centres of the Northern European book market: Amsterdam, Frankfurt and Paris. As, however, the logistics of such direct contacts were not at all easy, using professional help was obviously the most sensible thing to do.

Therefore, the find of a fascinating correspondence between Holste and a Venetian firm of booksellers with extensive international dealings deserves closer inspection, the more so since these letters not only shed some interesting light on the business of the book trade stricto senso, but illuminate the cultural context as well.67 I first propose to explore the background of Holste’s Venetian connections, and then go on to the technicalities of the book trade before ending with the more general aspects of Holste’s relationship with this firm, which his carteggio also allows us to grasp.

The carteggio opens with a letter by one ‘Giovanni la Noue’, sent from Venice and dated 17 January 1648. Gradually the letters reveal more information about the man who, for thirteen years, must have been one of Holste’s most important book suppliers. In 1648 Giovanni la Noue—Johannes de la Noué—arrived in the city on the lagoons,68 since the invention of printing one of the most important centres of the Italian book trade.69 Johannes came from the Netherlands, more specifically from the Dutch Republic, where his family, probably of the Roman Catholic persuasion, lived in Leyden and, later, in Utrecht: at one time he tells Holste his mother hailed from that town and now wants to return there, to prepare for her death.

Actually Johannes’s background was quite complicated. His mother, Catherine van Gelder, first married his father, Nicholas de la Noué, whose profession is given as ‘speelman’—musician, or fiddler. From this union, Johannes was born in Leyden in 1622; there also was a daughter, named Clasina. After Nicholas’s death, Catherine remarried with Johannes Origanus, a physician. When he died, too, his widow married for the third time, now choosing a lawyer, the German-born Andreas Fries. From this marriage at least one son was born, Andries Fries (1630–1675).70

Whether Johannes ever attended an academy is not clear. Nor do we know why he left the Low Countries for Italy and settled there. Obviously, however, he knew Holste before his arrival in Venice. He evidently had been in some sort of periodical contact with Barberini’s librarian, supplying him with books; for in 1648 he promises to ‘go on’ looking for new titles and notifying Holste about them, as indeed he does in the following year. Things were not easy, however, as Holste seemed to order titles which were not exactly recent and about which, therefore, the famous catalogues of the bi-annual Frankfurt Book Fair gave little or no information.71

The first letters reveal that La Noue has started some form of collaboration with the Venetian firm of Combi, booksellers. However, the precise nature of his involvement in the firm’s dealings is not yet clear. La Noue goes on corresponding with Holste on his own account though using the Combi’s address; also, he apparently is travelling asCombi’s Northern European agent, visiting the Autumn and Spring fairs at Frankfurt in 1650 and 1651. At the same time he is reconnoitring the Italian market for ‘ultramontane’ books, i.e. books published in, specifically, Northern, Protestant Europe; he asks Holste to advise him on the kind of titles people in Rome are likely to buy; he may then bear these in mind when visiting Frankfurt. However, he also notes no buyers will be found in Italy for any books written in German.72

In January 1652 the situation became clear, as La Noue entered into a real compagnia with Combi; the official name of the company was changed to “Sebastiano Combi e Giovanni la Noue, mercanti dilibri”.73

Apparently, the Combi firm had been in a shambles for several years, so the partners immediately started taking stock and preparing a catalogue. First, they sorted out the books in the warehouse, then went through the merchandise in the Combi-house and finally inventoried the masses of books in the shop itself.74 The job proved worthwhile: in October 1652, La Noue was able to write to Holste that a catalogue of all non-Italian titles in the firm’s possession was being printed and would speedily be sent to the customers. It must have appealed to the market immediately, for even in December a number of Holste’s orders from the Combi-catalogue could no longer be filled. From then on a catalogue was produced annually and sent to Holste, with the admonition to order quickly.75 The same occurred when the bi-annual Frankfurt catalogues arrived in Venice.76 The firm even supplied Holstewith the catalogues of the famous house of Merian.77

However, lest this lead us to think that the catalogues were the backbone of the business contacts between Combi-La Noue and their Roman customer—which would not be altogether untrue—let us have a closer look at routine proceedings.

Combi and La Noue bought books either to put them in stock or to a customer’s specific order. In the latter case, and if only one copy was involved, the amount of paperwork and time which the process entailed was quite staggering, the more so if we keep in mind how slow postal traffic and the transport of goods, either by land or by sea, often were.78 It might happen that Holste ordered one or more titles but forgot all about them during the long intervening period, which might last eight or nine months; he even might order them anew—or show surprise at their eventual, by then unexpected arrival.79 Holste’s orders, of course, could be based on information received from his friends and correspondents, or on his own reading. As indicated above, they could also result from his perusal of the catalogues forwarded to him by Combi and La Noue or from other information they gave him; he might receive printed catalogues, but also handwritten lists describing the firm’s own wares, which were then headed “nota di quello che è venuto ancora di Germania”, or “fattura de’libri quali aspettiamo di Francia” or even “libri novi venuti da Francfort fiero autumnale”.80

In these lists, some titles might have a marginal comment: “questo credo saria buono per Vostra Signoria Illustrissima”81—i.e. Holste will appreciate these—and they might end with a remark like “il restante sono libri quali non fanno per V.S.a.Ill.ma”—Holste will not like these. Obviously, the firm thought it knew the preferences of both Holste and his masters and, judging the titles which Holste underlined for ordering, they were often right in thinking so,82 although equally often Holste ordered considerably more.

After Holste’s orders had reached Venice, they were either executed on the basis of the firm’s own stock or placed with the appropriate, mostly non-Italian, Northern European contacts, or saved till the moment La Noue would depart for Frankfurt himself. The waiting had started, but the firm would keep Holste informed about any progress, especially if it took long, as when such structural or periodical inconveniences as piracy on the Mediterranean or the second Anglo-DutchWar imperilled the ships sailing from Paris or Amsterdam, and their costly cargoes.83

Once books had arrived in Venice, they first had to be cleared at the customs office, which, of course, involved some money.84 Other problems might arise, however, especially in the case of non-Italian books, which tended to be of special interest to the members of that complex institution, the Venetian Inquisition.85 From 1652 onwards, the gentlemen were more than usually inquisitive. The Venetian member was concerned about books that would have been considered Venetian property under the non-existing international copyright, but were often reprinted elsewhere and imported into the domain of the Serenissima,86 which enraged Venetian publishers. The papal member often was more distrustful of the contents of the ‘ultramontane’ books. Sometimes Holste, who was well aware of the problem as the papal Inquisition in Rome was severe, too, apparently decided to intervene and write to the Venetian Inquisition—to the obvious though discreetly voiced dismay of Combi-La Noue. They asked him to refrain from action as this might only cause further problems in the future, since the Serenissima was very jealous of its own authority, especially vis à vis papal interference.87

The problem was, of course, that one must assume Holste, like so many contemporary Italian intellectuals, to have been specifically interested precisely in the books forbidden by the Inquisition. To him and his kind, the Index must have served as an open invitation-cum-catalogue. This may explain the number of manuscript catalogues he compiled of books forbidden by the Holy Office, and the reasons why; it is a revealing list for Holste also notes that many books banned by the Inquisition are for sale after all, and, also, that many which are not for sale should be, the only reason for their forbidden status not being their heterodox content but the assumed heretic leanings of their author or even of the printer.88 If only because, through their Northern-European contacts, they could supply such forbidden books, a firm such as Combi-La Noue was a precious connection for such men as Holste and his patrons, as it was for the grand ducal librarian Antonio Magliabecchi, another intellectual well-served by the firm.

After clearance in Venice, the books were prepared for transport to Rome, which meant they had to be packed and put through customs again. Mostly, they were sent by ship to the harbour of Pesaro, on the Adriatic seaboard of the Papal States, where they were received by one Caspar de Meere, who must have been a merchant of Flemish origin residing in that port, and the obvious contact of the Dutch-born La Noue.89 From Pesaro, the books were taken overland to Rome by the transport firm of Giovanni Casoni, who delivered them to Holste. Every now and then a smaller packet destined for Holste was included in larger consignments meant for Roman booksellers.90 It also happened that a special parcel was made, such as the one containing Lieuwe van Aitzema’s rightly famous Dutch ‘History of the Peace of Westphalia’, “per essere carta grande”—being a large paper copy.91 Both Holste and his papal patrons, being highly sensitive to political-religious developments in the German lands, must have found this book, on the peace that had finally legitimized the Reformation states, particularly interesting.

Between the dispatch of the books and their arrival in Rome, a period of seven or eight weeks might easily elapse.92 And having waited impatiently for such a long time, Holste could sometimes not even just collect his new possessions, especially if the Inquisition decided to intervene in Rome, too. Thus we are intrigued as to the nature of the libelli Holste ordered from Germany and which Combi-La Noue procured for him without ever inquiring into their real character. When they were judged cattivi—‘evil booklets’—by the Roman Inquisitors, the companions asked Holste to send them back to Venice, though disclaiming any fault on their part, the more so as the Venetian Inquisitors had found nothing amiss; they advised him to return some other problematical works, on alchemy and the cabbala, as well.93

Incidentally, nor was the reading of books the only problem. Getting one’s scholarly products printed in Rome was not an easy matter either, as Holste told Mersenne, “à raison de l’ignorance et opiniastreté des censeurs inquisiteurs”.94

Of course, censorship was not confined to the Roman and Venetian Inquisition. In 1654, a book was published, paid for by the provincial Estates of the county of Holland, in the Dutch Republic. Copies arrived at the shop of Combi and La Noue in Venice, but a letter from the Leyden orientalist Jacobus Golius followed them, saying they must not be sold: the States of Holland had forbidden it. However, Holste had already got hold of one, though on the strict proviso that the transaction would remain secret. When he ordered a second copy and, in 1655, even a third one, the partners took fright and beseeched him to keep the utmost secrecy, or a commercial, diplomatic and political scandal would be the outcome. Although the title of this apparently controversial publication is never mentioned, I would like to suggest that it was probably Golius’s Greek translation of the Protestant version of Holy Scripture, which, in Venetian eyes, would have been a ‘hot item’ indeed.95 It would certainly explain Holste’s buying no less than three copies. For of course, a Greek translation of the Protestant Bible was a major instrument of printed propaganda in the continuous battle between Rome and the Reformation for the souls of the Eastern Christians, a battle in which Holste, as a member of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, was engaged as well.

After the receipt of the books, Holste had to effectuate his payments, normally by way of a bill of change, which usually seems to have been taken by the Casoni Firm, apparently acting as banker as well. The bills were always made out in Dutch guilders, counting for 3 Roman scudi each—a rate of exchange which was established between La Noue andHolste at an early moment during their business relationship; though it already represented a loss of five percent in 1652, which must have increased over the following decade, strangely, it was never altered.96 Under their agreement, Holste’s account was allowed to show a deficit of Hfl 60,- for a period of two weeks.97 It was not often that Holste remained in debt, but if he did, the firm, ever correct, informed him of it immediately, though couching their reminder in courteous terms and assuring him that “il commodo di V.S.a Ill.ma è sempre il nostro”98—if you are satisfied, we are.

Before the newly arrived books could be displayed in the library of their destination—the beautiful, sculpted room of the Biblioteca Barberiniana that now has been transferred to the Vatican Library, or the Alessandrina-room in the Sapienza Palace, or, of course, the oldest of the three, the great Sistine hall of the Vatican Library itself—the single volumes had to be bound. Holste used the services of Gregorio Andreoli, a Roman bookseller who dealt with him, too, but who, belonging to a dynasty of bookbinders, held for life the concession to bind the books of the Vaticana. His accounts have survived amongst Holste’s papers.99 They show what prices he charged for binding a single volume: for a duodecimo, 10 baiocchi had to be paid; for an octavo, between 10 and 15; for a quarto between 20 and 25, and for a folio volume anything between 40 and 100 baiocchi, or 1 scudo.

The books ordered and bought via the firm of Combi-La Noue had reached their destination. In bindings proudly proclaiming their ownership: the Barberini coat-of-arms with the ubiquitous three bees, or the heraldic devices of the successive popes under whom Holste served in the Vatican Library—the Pamphilij dove, or the Chigi mountains-cum-star—, they would now adorn the great halls designed to be the receptacles of knowledge, where Divine Wisdom would inspire Mankind.

From the very beginning, Combi and La Noue recognized Holste for what he evidently was: the influential representative of one and, after 1653, even of two great libraries in one of the centres of European culture, as well as a collector in his own right. He was also, of course, a well-known scholar whose expertise both in the field of librarianship and in matters of learning in general made him a much sought-after adviser to other scholars—who might be potential buyers of the Venetian firm, which therefore considered their Roman client well worth pampering a little.

Thus we find the companions throwing out the proverbial sprat clearly with a view to catching a whale. They continually try to impress their Roman customer with the fact that a lot of titles, though also for sale in the Urbs, are offered at considerably lower prices by their own firm. They even promise that whatever the price quoted in Rome, theirs will always be one scudo below. For a number of titles, they are willing to offer considerable discounts, up to 20 or 30 percent.100 Of course, they also pointed out that their international contacts gave them a real advantage over most Italian firms which concentrated on the domestic market only. Besides La Noue’s visits to the spring and autumn fairs at Frankfurt, over the years the firm also came to have contacts in Amsterdam, Basle, Geneva, Paris and Trier.101 In Antwerp and Cologne, too, men were acting as their agents, spotting new titles or receiving and executing specific orders.102 Thus, as early as the summer of 1652, the companions could express their hope to be well stocked in foreign books within the year.103

Undoubtedly, service must have improved even more when, in 1654, Andries Fries joined the firm of Combi-La Noue,104 who had already been helping his half-brother with orders placed in the Netherlands.105

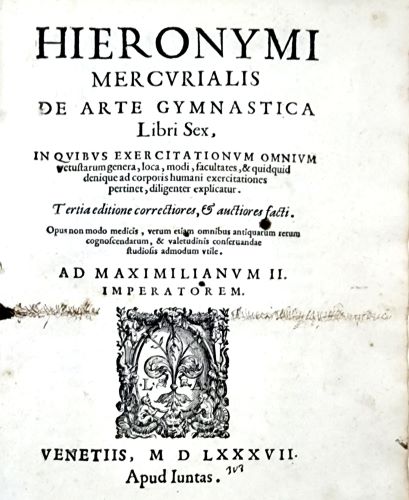

Andries had been a student at Leyden University from 1650 onwards, taking a degree in law. According to my sources, in the 1660s and 1670s he turned out to be something of a scholar-publisher as well, editing a number of literary works both in Amsterdam and in Antwerp. He even published a new edition of Hieronymi Mercurialis Foroliviensi “De Arte Gymnastica”, dated Venice 1672, almost certainly in collaboration with his half-brother. In these years, too, his contacts with the Moretus-family, the kings of Antwerp publishing, and with the Frankfurt book trade are documented by the Dutch sources. From 1670 to his death in 1675, he was a partner in the publishing house of J.J. Schippers, which was then directed by Schipper’s widow, Susanna Veselaer: in 1672 she named her companion co-heir of her possessions and owner of the firm, but as it turned out she outlived him.

When Fries first came to Italy, he was a 24-year-old, inexperienced young man, on the brink of a career that, as we know now, was largely made through his acting as the Northern-European representative of the house of Combi and La Noue. Whether he was totally unprepared or had already acted as an intermediary when Combi and La Noue employed the Leyden printer S. Matthijsz for their edition of Torquato Tasso’s Il Goffredo, which they then published in Amsterdam in 1652,wedo not know.

In November 1654, we find Fries in Venice, for business consultations with the companions; he also visited Rome—where Holste graciously deigned to receive him. In the following years, Fries not only acted as his half-brother’s agent in the Dutch Republic, selling Italian books, there, but also seems to have taken care of most of the firm’s acquisitions in the Dutch Republic, the Southern Netherlands, Germany and France, although his journeys might be hindered by such things as wars—but then the partners would hasten to assure Holstethat “si la pace tra Hollandesi et Inglesi si fa, subito andarà un di noi in Hollanda et Germania per far negotio”106: peace will allow them to resume business with the North again. Occasionally, Fries also travelled the Italian peninsula to explore new markets for books to be sold by Combi/La Noue.107

By using their contacts and offering this kind of service, Combi and La Noue could ask and expect Holste to recommend them to his friends, especially those who were about to start a collection of their own.108 Holste did not disappoint them.

Thus, the well-known scholar Carlo Dati—the author of a life of the ‘Ancient Painters’, who had profited from Holste’s deep knowledge of the Classics—became one of their customers, as did the archbishop of Citta Nuova mentioned above.109 Sometimes, the companions felt free to employ a little stratagem, sending Holste several titles suggestively “per mostra”, ‘on sight’, only, or, another ruse, several copies of one book which, as they wrote, might interest both him and his friends. Thus, in December 1653 Holste received six unasked-for copies of J. Glasius’s Philologia, which had been forwarded to him with the courteously commercial argument ‘that they are better for Your Lordship and his friends than for the people over here’, i.e. in Venice.110 Every now and then the stratagem worked and the companions were the better for it. If, however, Holste was not tempted, the firm correctly suggested he credit his account with the price of the books sent.111

One must conclude from the letters that the firm always acted correctly. If a book ordered by Holste did not arrive in Rome, a letter immediately followed, again crediting him for the amount due.112 However, when, once, Holste failed to provide an accurate description of a title he wanted and then did not accept the book that finally arrived, the companions firmly suggested that he find a Roman friend willing to buy it in his stead.113

As indicated above, Holste did not disappoint his Venetian booksellers, bringing them both individual and, far more important, institutional customers. Going through the letters sent by Combi-La Noueone cannot suppress a smile upon reading the fervent congratulations with which the companions greeted Holste’s nomination to the custodianship of the Vatican Library. Nor were they wrong in assuming this would markedly increase their business dealings with him: almost immediately, the new keeper started ordering books for the Vaticana through his Venetian friends114—after an experienced minor official of the library had explained to him what was the proper administrative way.115

Citizens of the Republic of Letters

Even from the early letters it is clear that the relationship between Holste and the Venetian company, or rather its Dutch partner, was not going to be a purely business one, only—although it has to be borne in mind that a number of services rendered in other fields did, of course, cement the firm’s position as one of Holste’s main book suppliers.

In 1652, Holste asked the partners to be of assistance to a high-born German—the Duke of Mecklenburg—and his secretary, who would be visiting Venice on their trip through Italy; this kind of service was to be a recurrent theme in the correspondence. Other Germans, too, amongst whom one who had been a friend of Holste’s in the Low Countries, were received and helped by the firm’s directors and assistants.116 On the other hand, Dutchmen or Flemings, looking for employment in Italy and asking their compatriot La Noue for help,were given letters of recommendation for Holste. There was one who said he was an experienced bookbinder; upon arrival in Rome he was actually taken into Holste’s service, but quickly found to be of no assistance at all. The partners were deeply repentant for having recommended such an unworthy person, but found a very tactful wording for it: ‘whenever they plan to render a service to Holste again, they will be even more circumspect’.117

The firm or rather, again, its Dutch partner, also acted as a news-agent. For although, of course, the Roman Curia was the centre of a wide, formally organized net of correspondents, whose avvisi, or news-letters, reached it from all over Europe, information supplied by well-connected individuals was always considered a valuable addition, especially by men like Holste, who acted as political advisers as well.118 LaNoue, with his contacts in the politically important Dutch Republic, could and did write to Holste about the vicissitudes in the North. When the Anglo-Dutch commercial and political difficulties resulted in war, Holste was told that “il nostro amiraglio Tromp ha ordine di combatter”; La Noue was afraid that a long and bloody struggle would be inevitable, for at stake was who ‘will be Master of the Seas’?119 Holste was interested indeed, and repeatedly asked to be kept abreast of further developments.120

That assistance could be mutual is shown by the Kircher-affair. The German-born Jesuit Father Athanasius Kircher (1601–1689), by 1655 a famous erudite, had been first recommended to Cardinal Barberini, Holste’s patron, by Holste’s friend Peiresc.121 From the1630s onwards Holste himself had done everything to further the learned Father’s scholarly career, trying to shield him from such tasks as were not suited to his bent of mind—e.g. being appointed spiritual adviser to the erratic Prince Frederick of Hesse, while, according to Holste, he rather should be enabled to travel to the Near East to pursue his studies. Holste felt that Kircher, especially after publishing his epochal Prodromus Coptussive Aegyptiacus (Rome 1636) should visit the sites of his research.122 In 1655, Kircher was looking for a bookseller with international contacts to distribute some of his books, and the firm of Combi and La Noue was interested indeed. With Holste acting as an intermediary, contact was established, but due to the opposition of the reverend father’s commilitones in Christ no contract was signed for several months, and when an agreement was finally reached in August, the terms seem to have been dictated more by the Society of Jesus than by the signatories themselves. Nevertheless, business was done, to mutual satisfaction, with Holste now acting as a banker receiving the bills of exchange endorsed by Kircher and transferring them to Casoni.123

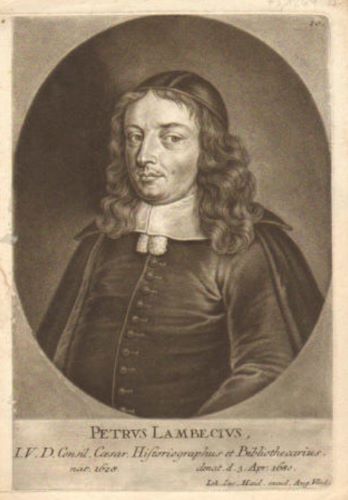

An interesting episode is the one which started in spring 1655, when a nephew of Holste’s, by the name of Lambeck, who had been staying with him, first appears in the letters of the Venetian booksellers. The young man in question was on the brink of leaving Rome for Leyden, to study at the university. Holste asked La Noue for the proper procedure and, more specifically, for the best way of selecting lodgings. LaNoue explained that it was advisable to rent a room, arguing against a students’ lodging-house on the grounds that living with a group would always distract a serious-minded young man from his scholarly purposes; besides, such a place would charge some 150 rixdollars, whereas the rent of a room would be about a 100 rixdollars, leaving one free to choose where to go for dinner and what to eat. Both La Noue’s friend ‘Giovanni Mayre’—surely the Leyden bookseller John Maire, of a well-known family of book traders operating in the first half of the 17th-century124—and Andries Fries would be helping the young man whenever necessary.125

At first I thought that with this letter I had discovered some unknown detail about the life of the famous Peter Lambeck (1628–1680). He was the son of Holste’s sister and her husband Heino Lambeck, schoolmaster of Hamburg’s St. James School.126 Born in 1628, he quickly became his uncle’s favourite, travelling, in 1646, first to the Netherlands, where he read geography in Amsterdam and law in Leyden and befriended such scholars as G.J. Vossius and J.F. Gronovius; he then went on to Paris, where he was received by Francesco Barberini, during his short exile, there, after the death of Urban VIII. He also came to know such friends of Holste’s as Gabriel Naudé and the Du Puy-brothers. He lived in Rome with his uncle for about two years before returning to Hamburg, by the same route. In 1652, he was appointed professor of history at the university. Ten years later, one year after his uncle’s death, he resigned his post, and on the instigation of Christina of Sweden converted to Catholicism, to which he had been attracted since his stay in Rome in 1647. Travelling to Rome once again, he finally ended up in Vienna, as vice-librarian of the Imperial Library and official historian to the emperor.

However, as appears from the dates, it cannot have been this learned Lambeck nephew whom we encounter in La Noue’s letters.127 Obviously, a younger Lambeck, too, had travelled to Italy, and in the summer of 1655 left Rome for Leyden. Henceforth, his letters from the Republic reached Uncle Holste via Maire-La Noue. In 1658 he was back in Italy. The ‘German Nation’ in Venice—the powerful association of merchants from North-Western Europe centred around the Fondaco dei Tedeschi on the Canal Grande—had asked him to become their syndic, or spokesman. La Noue gravely advised against his accepting the offer without Holste’s approbation, since a Dutch friend of his had held it once, only to find it involved great expenditure at the cost of one’s private means and left no time at all for study and scholarship. Holste’s nephew did stay on in Italy, however, for we find a Lucas Lambeck taking care of Holste’s financial affairs between 1658 and 1660, endorsing payments to, amongst others, the firm of Combi and La Noue.128 We may conclude that he was probably Peter Lambeck’s younger brother. What became of him after his uncle died in 1661 is not known.

With Holste’s death, we also lose track of the further vicissitudes of the firm of Combi and La Noue. Some disconnected data are known, though. Obviously, the firm continued to prosper. Perhaps Sebastiano Combi died in the1660s, for in those years his Dutch partner alone was honourably referred to as “eruditorum omnium fautori eximio et bibliopolae apud Venetos non postremo”. In 1675, Giovanni washeir to part of his half-brother’s estate, inheriting quite a number of books, which he then put up for sale, naming the Amsterdam publisher Hendrik Wetstein as his representative. His sister Clasina de la Noué and her Schilperoort children were Andries Fries’s general heirs.129 The firm of Combi and La Noue was still in business after 1686, when the Dutch booktrader Marc Huguetan was in debt to them.130

Conclusion