The rhetoric of the Persian Wars was central to Alexander’s goal of forging panhellenic unity.

By Dr. Christos Kremmydas

Head of Department (Classics)

Royal Holloway

University of London

Introduction

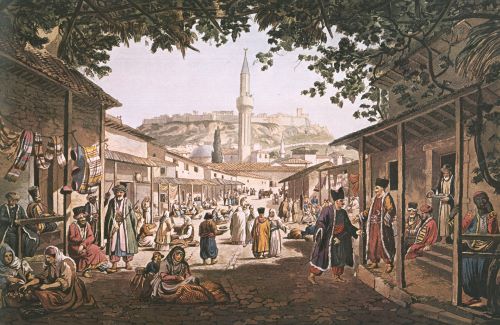

In 3361 the twenty-year-old son of the assassinated King Philip, Alexander III, inherited not only his father’s throne of Macedon but also his war against Persia. The first abortive episode of that war, little more than a reconnaissance mission under Parmenion and Attalus, had already been played out in north-western Asia Minor. Along with this war, Alexander inherited his father’s propaganda2 that marketed the war to the Greeks of the mainland as a revenge campaign.3 The idea of a panhellenic venture against the Persians to avenge the wrongs committed in the Persian Wars one hundred and fifty years before had been popular with the Greeks for over a century4 and had recently received the backing of a prominent Athenian intellectual, Isocrates.5 This idea of a collective expedition of the Greeks against the Persians was sustained by Alexander at least until 330 when the royal capitals of the Persian Empire were captured.6

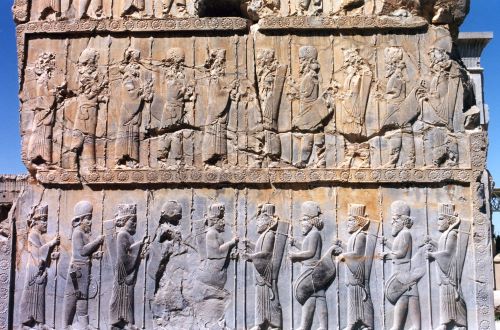

Alexander’s panhellenic rhetoric employed powerful and long-cherished slogans, such as ‘freedom of the Greeks’ and ‘autonomy’7 in order to rally the Greeks behind his campaign into Persia. While he was in western Asia Minor he even appeared to manipulate aspects of democratic ideology,8 even though he was not necessarily operating with a consistent policy of spreading democracy to the East. Besides verbal means of persuasion, Alexander’s propaganda was also non-verbal. He often manipulated the visual to get his message across to his intended audiences, Macedonian, Greek, and later Persian, too. His use of images and symbols in statues,9 coins,10 and wall-paintings was an effective way of steering public opinion where it suited him, namely the panhellenic war against the Persians (from 336 to 330).

Alexander’s panhellenic propaganda was doubtless a means to an end but its use brought up tensions with Greek communities of the mainland. After all, the very Greekness of the Macedonians was disputed in some quarters. Paul Cartledge believes that for the Greeks of the mainland:

It was Macedon, not the Great King, which they thought was the real, or at any rate the more immediately present, danger and enemy. For many Macedonians, conversely, Greeks were members of a recently defeated and so despised people who did not know how to conduct their political and military life sensibly. This, I think, is the true light in which we must view Alexander’s inherited panhellenic propaganda. If he kept it up until 330, despite its increasing awkwardness, this was because it was his only means of attempting to conciliate the considerable amount of hostile Greek opinion and so of helping to keep the Greek mainland quiet.11

In the field of propaganda, Alexander inevitably found himself antagonizing Athens, a former hegemonic power in the Greek world. He no doubt had hoped to take Athens on board and use her as a powerful asset in his panhellenic venture to the East. One even gets the impression from some sources that Alexander was adopting Athenian propaganda methods reminiscent of the fifth-century Athenian Empire and even Athenian moral traits in order come across as more acceptable to the Greek world and Athens in particular.12 Take for instance the use of philanthrōpia and epieikeia (two characteristically Athenian traits) to denote the way he treated the Athenian envoys in the aftermath of the sack of Thebes (and Greeks in general throughout his reign). But Athens, too, was spared due to ideological as well practical reasons (Arrian, Anab. 1.10.6):13

Alexander relented, whether due to his respect for Athens, or because of his haste to launch the expedition into Asia he did not want to leave any feeling of suspicion behind among the Greeks.

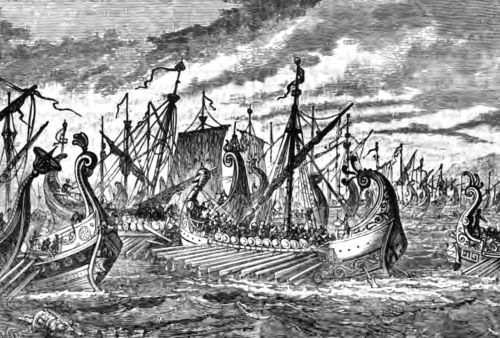

Being a pragmatist at heart he realized the practical as well as ideological benefits of having the city on his side. On the one hand, he appreciated the enormous ideological potential held by the city if his panhellenic rhetoric was going to be credible while, on the other, he needed its material help (i.e. naval resources) and also had to secure his back as he was launching his punitive expedition to the East. Athens reluctantly decided to join the panhellenic campaign,14 but there is no denying the fact that the Athenians were less than enraptured by the young Macedonian king. Their military cooperation was no more than half-hearted. We know that at the start of the campaign Athens had the potential to contribute far more than the twenty ships that eventually joined Alexander’s naval force in the early stages of the war (until the disbandment of Alexander’s navy in 333).15 Meanwhile, many Athenians, either disillusioned with the city’s decision not to fight Alexander or simply cash-strapped, joined the forces of the Great Persian King as mercenaries.16 Repeated calls to resistance and revolt from 335-23 were unheeded as the Athenians preferred to keep as low a profile as possible.17 Despite this ostensible acquiescence or passivity towards Alexander, many in Athens continued to harbour visions of leadership in the Greek world, as they had done throughout the first two-thirds of the fourth century in the days of the Second Athenian Naval Confederacy.18

The conceptual pool from which both Alexander and Athens drew slogans and ideals was restricted, thus leading to tension between their competing discourses. Terms such as ἐλευθερία, and αὐτονομία were employed by Alexander in his panhellenic expedition, while Athenian politicians were using the same terms in their internal blame games (as invective in the courts) or were calling for the freedom of Greece from Alexander.19 Whereas Alexander was bestowing autonomy on cities allied to the League of Corinth, there were protests in mainland Greece against Macedonian intervention in their internal affairs.20

A pivotal position in Alexander’s propaganda was occupied by the Persian Wars. The rhetoric of the Persian Wars was central to Alexander’s goal of forging panhellenic unity in view of the expedition to the East. At the same time it was asserting his Hellenic identity. However, the manipulation of this key milestone in Hellenic history by Alexander’s propaganda created further tension in his relationship with Athens as the city justified its former hegemony in Greece through its role in safeguarding Greek freedom during the Persian Wars.21 Therefore, Alexander’s Persian Wars rhetoric antagonized Athens’ rhetoric with regard to the panhellenic effects of their own contribution to the Persian Wars.22 Alexander repeatedly attempted to mollify the Athenians as long as they were vital to his propaganda but ultimately he was unsuccessful. The battle of Marathon, in particular, demonstrates the limitations he faced in terms of his rhetoric.

Six Episodes in Alexander’s Persian Wars Rhetoric

In what follows I will explore in chronological order a number of episodes highlighting the ways in which Alexander manipulated events and ideas relevant to the Persian Wars. In some of these, the links to Athens are made explicit.

1. The Persian Wars rhetoric was inaugurated by Alexander early on in his reign. It was employed in 335 after the sack of Thebes in order to justify this brutal act to the rest of the Greeks. As is well known from Herodotus, the Thebans had ‘Medized’ during the Persian Wars (7.132), therefore at the start of a panhellenic campaign they should be punished for it, especially as they now stood in the way of the hēgemon of the Greeks. After a long digression enumerating disasters on a similar scale from fifth- and fourth-century history,23 Arrian reports the view that the fate of Thebes was their overdue punishment, divinely ordained, for their ‘medism’ in 480 (1.9.7):

This was divine wrath, justice was being meted out to the Thebans after a long time for their betrayal of the Greeks in the Persian wars … and for the ruined state of the Plataean countryside, on which the Greeks, drawn up in battle order against the Persians, had repelled the threat to Greece, and, finally, for voting to enslave the city of Athens when a proposal was put before the allies of Sparta ….24

One may safely attribute this reference to Theban ‘medism’ to Alexander’s propaganda rather than to the historian himself. Although the larger section of which this passage forms part is a moralizing excursus by Arrian on the theme of divine wrath (μῆνιν)for wrongs committed in the past (1.9.6),25 the connection between Theban ‘medism’ in 480 and retribution in 335 is more likely to have been established by Macedonian propagandists first: Callisthenes and Ptolemy (he is cited at 1.8.1) are two obvious candidates.26 The reference to the Theban vote to raze Athens after the end of the Peloponnesian War (Xen. Hell. 2.2.19-20) affirms the attribution to Macedonian propaganda as it is consistent with the systematic courting of Athens by Alexander before and during the campaign into Persia.

Reference to the wrongs committed by a Greek city during the Persian Wars was the only way of justifying the brutal treatment it suffered at the hands of Alexander.27 Thebes was thus associated with Xerxes’ barbaric treatment of Greek cities and is rightfully placed on the ‘hit-list’ of Alexander’s revenge campaign. This, then, was an intelligent propaganda coup on the part of Alexander that aimed to maintain the pretence of the upcoming panhellenic venture against the Persians.

2. One of the best-known episodes of Alexander’s campaign comes in the immediate aftermath of the victory at Granicus, in 334. Alexander carries on his courting of Athens as he manipulates the precedent of the Persian Wars for his own panhellenic propaganda.28 The victorious Macedonian king sent the goddess Athena three hundred Persian panoplies29 inscribed with the famous epigram ‘except the Lacedaemonians’.30 According to Arrian (1.16.7):

He sent to Athens three hundred Persian panoplies as a dedication to the goddess Athena on the Acropolis; he ordered this inscription to be inscribed on them: ‘Alexander, son of Philip and the Greeks, except the Lacedaemonians, dedicate these from the barbarians living in Asia’.

Alexander was clearly trying to portray himself as the avenger of Athens’ patron goddess.31 The Athenian temple(s) on the Acropolis had been famous victims of Xerxes’ barbarity in 480 (Hdt. 8.53), therefore Alexander’s gift of the Persian panoplies to Athena was meant to be a token of revenge exacted. What is more, he would thus establish a visual reminder and a symbolic presence on the Athenian Acropolis. At the same time, one cannot help noticing Alexander’s ‘winking’ at the Spartans: the number three hundred would have implicitly reminded them of their heroic sacrifice for Greece at Thermopylae, which is now juxtaposed with their refusal to engage in the panhellenic campaign led by Alexander. Nevertheless, this highly symbolic gesture looks more like an attempt to placate the Athenians in front of a panhellenic audience rather than either Athena or the Lacedaemonians.32

3. In 332 after his first victory over Darius at Issus, Alexander received a letter from the defeated Persian King, in which the latter was requesting the release of his captive family and an amicable settlement to the war (Arrian 2.14.1-3).33 Alexander’s response is, in essence, a document of Macedonian propaganda with multiple recipients: the Macedonians themselves, the cities on the Greek mainland, the Persians and peoples inhabiting the vast Persian Empire. At the very outset, it contains a succinct summary of the expedition’s raison d’ être (Arrian 2.14.4):

Your ancestors invaded Macedonia and the rest of Greece and did us great harm, although we had not wronged them prior to that; I have been appointed hēgemon of the Greeks, and invaded Asia wishing to punish you, Persians, for something you started.

Although in this particular instance there is no mention of Athens, Alexander’s special interest in having the city on his side resurfaces in the immediate context. The historian discusses how Alexander dealt with Greek mercenaries captured in the battle of Issus. Four individuals are singled out, two from Thebes, one from Sparta, and Iphicrates, the son of the famous Athenian general of the first half of the fourth century. According to Arrian (2.15.4), Iphicrates junior was honoured because of Alexander’s friendship for Athens (φιλίᾳ τε τῆς Ἀθηναίων πόλεως) and the memory of his famous father’s reputation. After his death, his bones were repatriated in another symbolic, magnanimous gesture.

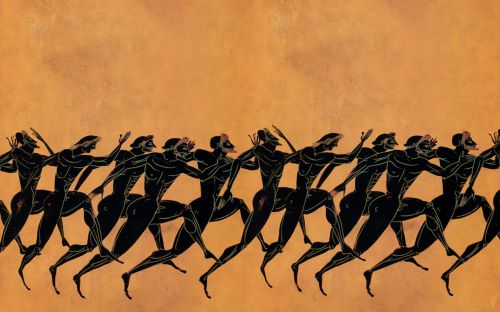

4. Alexander’s decisive victory over Darius at Gaugamela in 331 signalled his defeat of the Persian Empire and the end of the military operations in the War of Revenge. He could now assume the coveted title ‘Lord of Asia’ (Plut. Alex. 34). In two symbolic gestures harking back to the Persian Wars, he reserves Plataea in Boeotia and Croton in Southern Italy for preferential treatment (Plut. Alex. 34.1-2):

… he wrote to the Plataeans in particular that he would rebuild their city, because their ancestors had given their territory to the Greeks in the fight for freedom. He sent also to the people of Croton in Italy part of the spoils, honouring the zeal and bravery of their athlete Phäyllus, who, at the time of the Median wars, when the rest of the Greeks in Italy refused to help the Greeks, fitted out a ship at his own expense and sailed to Salamis, in order to take part in the danger there.

Plataean territory was hallowed ground for the Greeks since the last land battle of the Persian Wars had been fought there in 479 (Hdt. 9.58-75)35 and Plataea had been linked with the Greek war of freedom ever since. Alexander’s promise to rebuild the city was a propaganda gesture meant on the one hand to stress that the war of revenge against the Persians was approaching its conclusion while, on the other, sending yet another strong signal to Thebes, the menacing neighbour of Plataea.

Phayllus, the famous Pythian victor,36 had commanded Croton’s warship in the battle of Salamis, the only contribution of the western Greeks to the Greek armada in 480 (Hdt. 8.47). Although distant Croton had not taken a part in Alexander’s expedition as far as we know, he still wished to include it in his Persian Wars propaganda, albeit belatedly. He was thus extending the reach of his panhellenic venture to western Hellenism as well37 and Phayllus provided a prominent figurehead, well known in the Greek world beyond his hometown.

5. After Gaugamela and the effortless capture of Babylon, Alexander continued his long march into the Persian heartland, while the defeated Persian King fled to Media. The destination was Susa, one of the Persian royal capitals. After getting there in twenty days, Alexander laid his hands on the coveted royal treasure. What is more important from the point of view of his propaganda is the retrieval of highly symbolic artefacts. According to Arrian (3.16.7-8):38

He captured there a great deal more, namely the objects which Xerxes took away from Greece, and the bronze statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton among other things. Alexander sent them back to the Athenians and they now stand in Athens in the Cerameicus.

Three years after the start of his campaign, despite the fact that Darius has already been comprehensively defeated, Alexander was still preoccupied with the reception of his panhellenic campaign by the Athenians and wished to win them over. Whereas the three hundred panoplies presented Alexander as the avenger of the goddess Athena, this episode projects him in the role of the protector of Athenian democracy. The statues of the tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton by Agenor embodied the end of the Peisistratid tyranny in the minds of many Athenians, and heralded the start of Athenian democracy.40 Therefore, Xerxes’ ‘abduction’ of the original tyrannicides’ complex was a highly symbolic blow against Athenian democracy. Although the Athenians soon commissioned a new complex (by Critius and Nesiotes), Alexander’s gesture reminded them that this remained very much an open wound in Athenian collective memory.

Therefore this is a highly symbolic act in Alexander’s propaganda that links the rhetoric of the Persian Wars with the effort to win Athens over. It is another token of revenge against the Persians as his campaign approaches its closure. But if Athens was the primary objective of this act of propaganda, the rest of the Greek world was also meant to watch on.

6. The return of the tyrannicides’ statues from Susa looks forward to the last and probably most potent acts of Alexander’s panhellenic war of revenge, the sack of Persepolis and the burning of the Royal Palace. Here, too, the connections to Athens are strong. The capital of Persia, ‘the most hateful of cities in Asia’ and the ‘wealthiest under the sun’,41 is therefore singled out for the harshest treatment as the seat of Persian barbarism. It is sacked, plundered by the Macedonians, and its palace is burned down (Diod. 17.70.1):

Alexander declared to the Macedonians that Persepolis, the capital of the Persian kingdom was the most hateful of the cities of Asia, and gave it all over to his soldiers to plunder, except the royal palace.

This certainly leads the war of revenge to a dramatic closure as Alexander and the Macedonians take full revenge for Xerxes’ sack of Athens in 480. Yet, in this instance, we are witnessing a striking role-inversion with decadent, corrupt overtones. While the giving over of the city to plunder is attributed to Alexander himself, a hetaira from Attica spurred him on to commit one of the most brutal and uncalled-for actions, the burning down of the Persepolis palace. Thais and other women play a key role in order to humiliate the Persians further and magnify the revenge (Diod. 17.72.2-4) for the impieties committed by the Persians in Greece (Athens in particular).

The Persian Wars and the Absence of Marathon

It is obvious from the discussion of these episodes that, while Alexander did allude to the Persian Wars in order to sustain the rhetoric of a panhellenic revenge campaign, he only did so in rather vague terms while throwing into relief any Athenian connections wherever possible in order to placate Athens. References to specific battles of the Persian Wars in the Alexander historians were few and far between. It could be argued that their infrequent mention can be attributed to the historians’ own interests and the literary tastes of their own age and not necessarily to Alexander’s own propaganda. Drawing parallels to well-known historical events served the wider moralizing agenda of Roman historians of the Imperial period. Three key battles, Salamis, Artemisium, and Plataea,42 are mentioned in passing, while the role of the Athenians and Lacedaemonians is also stressed in rather general terms.43 Even so, the omissions are quite striking: Thermopylae (see the above discussion of the three hundred panoplies incident) and Mycalē from the key battles of 480/79 (and there was quite a bit Alexander could do rhetorically with regard to Mycalē: see the description of his campaign at 1.18-19), and, of course, Marathon in 490. Neither Thermopylae nor Marathon are left out accidentally.

Since the slogan of the ‘freedom of the Greeks of Asia Minor’ was part of Alexander’s panhellenic propaganda and Athens’ victory at Marathon in 490 was central in the Greek wars of freedom against the Persians, why did Alexander shy away from referring to this battle? Why was Marathon off-limits for Alexander’s propaganda?

An anecdote dating to the 350s, twenty years before Alexander’s invasion into Persia, is indicative of Athenian public discourse from the 350s to the 320s and demonstrates how loosely past history could be related in fourth-century Athens. Towards the end of the Social War in 357-56, Chares, an Athenian condottiere acting in a private capacity, claimed a famous victory against the forces of the Persian King (the Persians under the leadership of Tithraustes).44 Despite the fact that his force comprised mercenaries and he was siding with Artabazus, one of the rebel Persian satraps, he was still able to gloat that his victory over the Persians was ‘sister to that of Marathon’ (Schol. on Dem. 4.19). We do not know, of course, whether Chares’ propaganda was received by his contemporary Athenians with admiration or mirth. What is certain though is that it indicates the flexibility with which the Athenian victory could be reshaped and adapted to suit propaganda, despite the obvious lack of parallels: the only thing that Chares’ victory had in common with Marathon was the fact that an Athenian general was fighting the forces of the Persian King. The absence of Marathon, on the one hand, illustrates the limits of Alexander’s Persian Wars rhetoric while, on the other, it speaks volumes about Athenian propaganda at the time.

It is obvious that from a purely semiotic perspective Marathon was not as suited for panhellenic ‘consumption’ as other victories in the Persian Wars (e.g. Salamis or Plataea). Although the Athenians were joined by Plataeans in the battle, the latter’s assistance was progressively ironed out of fifth- and fourth-century retellings of the story. The perception of Marathon as a solely Athenian exploit was too deeply ingrained in Hellenic consciousness for Alexander to be able to manipulate it rhetorically.45 Alexander faced an even bigger obstacle with regard to Marathon. Shortly before 351 his father, Philip, had raided Marathon, captured Athens’ sacred trireme, and thus terrorized the city (Dem. 4.34). We do not know whether anti-Macedonians in Athens exploited this parallel to 490 (Philip invaded the very territory where Athens had repelled the Persian invasion) in their anti-barbarian, anti-Philippic rhetoric, but the memory of this incident would have doubtless been too strong a mere two decades later for Alexander to invoke Marathon in his Persian Wars rhetoric.

However, an exploration of the Athenian political scene from the 340s to the 330s may provide further clues as to Alexander’s inability to harness the rhetorical potential of this battle. Since the ascendancy of Macedon to a position of power in the Greek world under Philip II there was a division of opinion in Athens regarding the best anti-Macedonian strategy. This debate gained in intensity, especially after the defeat at Chaeroneia in 338 and later during Alexander’s expedition into Persia.46

Competing Athenian Discourses

Athens avoided challenging Alexander militarily but the mood in the city remained generally hostile towards Alexander, and his panhellenic rhetoric was challenged in Athenian public fora. Demosthenes is alleged to have predicted that Alexander would be trampled under the hooves of Darius’ horses at Issus (Aesch. 3.164), yet he was reluctant to embroil Athens in Agis’ revolt. Athenian hostility towards Alexander and Macedon was probably enhanced by a sense of inadequacy or inability to take him on on the field of battle.

A patriotic mood, which was strengthening despite or in response to the repeated setbacks since Chaeroneia, is manifested in three ways:

i) On a very practical level, Athens passed reforms in areas thought to have led to the setbacks of the previous decades. The reform programme was orchestrated by Lycurgus: public finances as well as naval resources improved, while the Athenian military was re-organized and Athenian defences were repaired and strengthened.47

ii) Other measures suggest a renewed emphasis on civic, democratic ideology as a response to the outside threat posed by Alexander: Eucrates’ anti-tyranny legislation48 and the (re)introduction of the cult of Demokratia indicated an apprehension of tyranny and a desire to safeguard the democratic constitution.49

iii) Glimpses of Athenian patriotism can also be seen in forensic oratory post-Chaeroneia. Two speeches from 330 are Demosthenes’ speech On the crown and Lycurgus’ Against Leocrates. In the latter, Lycurgus uses the terms ‘liberty of the Greeks’, ‘courage’, ‘virtue’, and ‘the city’s glory’ as inspirational slogans. A central section in his speech (68-87) is occupied by a reference to the Persian Wars, the Athenian ephebic oath, and the events of mythical times (king Codrus and his sacrifice) in order to highlight the Athenian exploits in the service of Greece, which won the city its position of supremacy in the Greek world. This is proper Athenian panhellenism and Marathon is one of the episodes singled out (Lyc. Against Leocr. 104):

These are the epic lines [Iliad 15.494], gentlemen, to which your ancestors listened and such are the deeds which they emulated. They thus became so brave as to be willing to die not just for their own country but also for the whole of Greece as their common country. Certainly those who were drawn up in battle against the barbarians at Marathon defeated an army from the whole of Asia and won, at their own peril, security for all Greeks.

Around the same time, Demosthenes delivered his famous speech On the crown (Dem. 18). He explains the failure of his policy and defeat at Chaeroneia by attributing it to the will of the gods. Like Lycurgus, Demosthenes’ panhellenic rhetoric is meant to counteract Alexander’s propaganda. Athenian cooperation with Thebes was justified. Even the problem of Theban ‘medism’ in the Persian Wars is overlooked by referring to the myth of the Heraclidae (‘Demosthenes’ decree’: Dem. 18.181-87). The point that Demosthenes tries to drive home is: ‘there is no shame in failure when fighting for the freedom of the Greeks’. Thus, the defeat at Chaeroneia is placed in the same line of Athenian military exploits that extended back to Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea (Dem. 18.208):

But no way, you cannot have done the wrong thing, men of Athens, when you took upon yourselves the danger for the sake of freedom and salvation for all. I swear it by our ancestors who first took upon themselves the danger at Marathon, who were drawn in battle order at Plataea, who fought in the sea-battles at Salamis and Artemisium, and by all the brave men who are buried in our public tombs. They were buried there by a city who considered them all worthy of the same honour, Aeschines, not just the successful and the victorious.

One could argue that these references to the famous battles of the Persian Wars are simply rhetorical exempla reinforcing Demosthenes’ arguments as he accounts for his long public career. After all, in the same trial Aeschines, too, had referred to the glorious Athenian victories of old.50 I would like to suggest, however, that the references to the Persian Wars in both speeches are more than rhetorical topoi. They reflect the prevalent Athenian civic discourse at the time; a discourse that sought to reinforce the Athenian contribution to the freedom of the Greeks and remind the Athenian audience of their position of leadership in the fight against the Persians. The Athenian Persian Wars rhetoric had first made its appearance around the mid-fourth century when the Macedonians started being perceived as the threatening ‘barbarians’. It was in this period that a number of forged inscriptions relating to the Persian Wars made their appearance in Athens.51 This patriotic discourse intensified during Alexander’s reign and had a bearing on the new labours in the cause of freedom that Athens was anticipating.

In the mid-320s the clouds of war had started gathering. Rumours of war were already spreading before the proclamation of Alexander’s Exiles Decree in 324. Athens was preparing mentally and militarily for a final showdown which ultimately came after Alexander’s death in 323. Athens had forfeited the position of leadership in the Greek world and needed a morale-booster in the dark days of the late 330s and 320s. The Persian Wars from Marathon down to Plataea provided that inspiration to carry the torch of Greek liberty as its only genuine defenders. And as it turned out, the Athenian Persian Wars rhetoric outlasted and outlived Alexander’s.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Contribution (199-211) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.