The remarkable wealth of the London vintners in the fourteenth century created a distinctive locus.

By Dr. Christian Steer

Honorary Visiting Fellow

Secretary of the Harlaxton Medieval Symposium

University of York

Introduction

On 27 November 1481, a licence was issued to the executors of Thomas Kent (d. 1469) clerk of the king’s council and parishioner of St. James Garlickhithe where

in fulfilment of the intention of the said Thomas, who considered that the seven chaplains of the chantries in the church of St. James aforesaid conversed more among laymen and wandered about rather than dwelt among clerks as was decent, to found a perpetual commonalty of the said chaplains1

The 1548 chantry certificates suggest at first glance that the foundations of these chantries in St. James Garlickhithe by wealthy city merchants were no different from those elsewhere.2 These good works were bequeathed by the well off for the benefit of their souls and for the common good of the parish; substantial endowments were bequeathed to the rector and churchwardens – and their successors – to provide salaries for ancillary chaplains, repairs to the property and charitable enterprises for the poor. And in return the benefactors of St. James were to be commemorated and remembered in perpetuity. But these similarities in form mask variations in the distribution of such benefactions across medieval London: there were particular ‘hot spots’ where local characteristics and influences led to a greater popularity of commemorative activities in certain parishes than in others. This essay argues that the remarkable wealth of the London vintners in the fourteenth century created a distinctive locus in their parish of St. James Garlickhithe, where wealthy and politically important men had their city mansions.3 This case study will show that public displays of piety were made in this particular church on a notably spectacular scale and where, significantly, different forms of commemoration were brought together to serve the interests of the living and the dead.4 The function of the tomb as an aide memoire for prayer needs little rehearsal but at St. James a synergized relationship between funerary monuments and the Offices of the Dead affords a rare opportunity to examine the way in which the commemorative jigsaw was applied. Such enterprises were to enable these merchant princes to reach ‘the Saints in Paradise’ through charitable acts and commemoration within their parish.5 It is the purpose of this essay to examine the characteristics of this hot spot of urban commemoration and to examine the reasons why Thomas Kent went to such lengths to reorganize a ‘perpetual commonalty’ – a pseudo college – in this particular city church.

The Parish and Church of St. James Garlickhithe

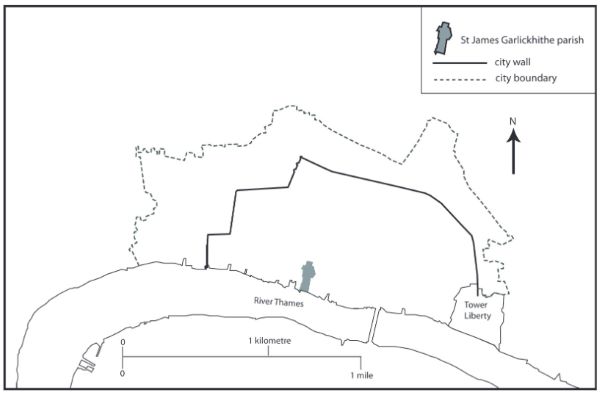

St. James Garlickhithe was one of many riverside parishes with direct access to trade, commerce and to the royal courts at Westminster and Greenwich (Figure 1).6 The parish, on the northern banks of the Thames between St. Martin Vintry to the east and St. Michael Queenhithe to the west, was popular among the city merchants of medieval London who resided in richly furnished mansion houses in the parish. One notable resident, the Flemish merchant Richard Lyons (d. 1381), lived in a townhouse filled with luxurious tapestries, leopard skins and ermine with hanging curtains of red and blue, embroidered with lions in his bedchamber. One item of immense luxury was a pavilion set over Lyons’ bathtub which provided privacy during his ablutions.7 Courtiers such as Thomas Kent were also resident in St. James together with members of the aristocracy such as William Herbert, earl of Huntingdon (d. 1491), who, with his wife Katherine – illegitimate daughter of Richard III – was another important parishioner of St. James Garlickhithe.8 It was in this church, alongside members of the Stanley family, that Katherine was buried, probably shortly after her father’s death in 1485. Stow’s record of now lost monuments reveals a mausoleum of twenty notable burials in this church, among whom were Thomas Stonor (d. 1431), MP for Oxfordshire, and the lawyer Nicholas Stathum (d. 1472).9 Proximity to the river also made this a popular parish among artisans such as those joiners who set up home in the parish, which provided ready access to imported timber.10

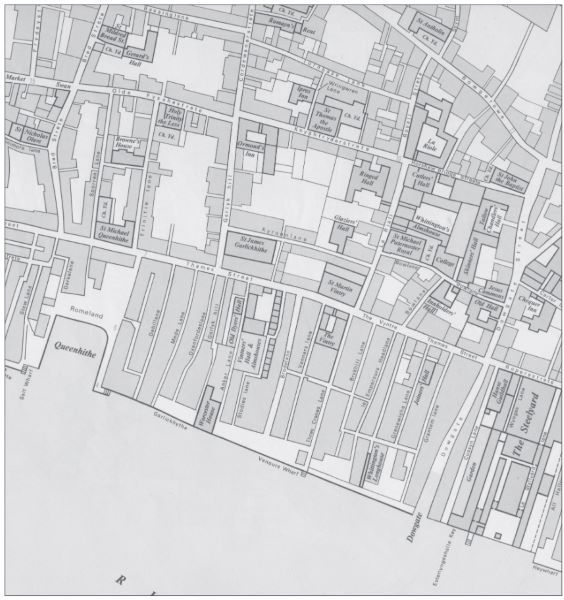

The church was rebuilt in the fourteenth century through the patronage of one principal benefactor, the vintner and former sheriff (1326–7), Richard Rothing (d. 1346).11 Documentary and archaeological evidence from elsewhere in the city suggest that it was unusual for complete rebuilds of parish churches to take place during the fourteenth century: the only other known instance was at All Hallows the Less, rebuilt through the largesse of Sir John Pulteney (d. 1349).12 Rothing and Pulteney effectively re-founded these two parish churches. There are 117 surviving wills for parishioners of St. James Garlickhithe in the period 1340 to 1500. These reveal the development of a modest-sized church, richly equipped and furnished by generations of parishioners and led by a rector served by a team of auxiliary chaplains, two clerks and up to four churchwardens.13 These wills reveal that Rothing’s church was of conventional design with the nave and chancel separated by a rood screen.14 It was Rothing’s son, John (d. 1376) – another vintner – who completed his father’s building project with a bequest of £200 to pay for the construction of a belfry.15 The tower was already in place because it was here that John requested his own burial in the middle of the campanille. He left a further 20 marks for his parents Richard and Salerna to be exhumed and reburied with him. John Rothing’s chaplain, Roger Hunt (d. 1393), is the only other testator from St. James known to be buried in the bell tower asking in his own will to be interred at the feet of his dead master, for whom he acted as executor.16 The bell tower seems to have served as the western entrance to the medieval church from Garlick Hill (Figure 2) and was thus a highly visible place of burial. John Rothing evidently took care to ensure that the graves for himself and his parents should be seen by subsequent parishioners and visitors to St. James as they entered the church. Rothing’s bequest of £200 was also to pay for a door to the north part of the church which was probably the entrance to the north aisle from Kyroun Lane – this aisle was certainly in place by 1417 when the draper Thomas Gipping/Kipping alias Lincoln (hereafter referred to as Thomas Lincoln) requested his burial there.17 By c.1430 a lady chapel and south aisle had also been built.18 A notable reference to ongoing maintenance work is found in the will of the rector William Huntingdon, who died in 1455, when he left a bequest of 5 marks for the ‘renouelyng [renewing] of the quere over my grave’.19 It is unclear whether a memorial was to be carved onto the new slab over the rector’s grave but this request nevertheless reminds us of the constant renewal of floor space with new flagstones and slabs routinely put in place. Burial at St. James could only take place inside the church – there was no parish graveyard and those parishioners unable to afford the fees for intramural burial were instead buried in the cemeteries at St. Paul’s Cathedral.20 The written records do not describe the form of monuments within St. James Garlickhithe, but from the descriptions given in the wills of parishioners, we learn that these were flat, floor-facing ‘marble stones’ and thus a mix of incised slabs and commemorative brasses.21

Monuments were but one means of commemoration and the generosity of these parishioners was extended through the endowment of perpetual and short term chantries, the foundation of a fraternity of St. James, and through the routine establishment of anniversary services and obits. The joint benefits of this ‘spiritual armoury’ for the donor and to the community are well known22 and their juxtaposed relationship provided ‘a cult of the living in the service of the dead’.23 The vintner John Longe (d. 1363), for example, left £20 to the church to employ one chaplain to celebrate a three-year chantry for his soul, the souls of his parents and whomsoever his executors chose.24 This priest was to be paid an annual stipend of £6 13s 4d.25 The chaplain employed was probably the Master Henry who received a bequest of 13s 4d in the 1364 will of John de Cressingham (d. 1365), another wealthy parishioner. Cressingham also left 6d to each chaplain celebrating in St. James which suggests that by 1365 there were at least two priests supporting the parish liturgy, and perhaps more.26 By 1375 a collective enterprise was also underway where the ‘good men’ of the parish organized the foundation of a fraternity dedicated to St. James in the church.27 Members were to pay an annual membership fee of 6s 8d, there was to be a livery, an annual feast and the members of the brotherhood were to attend the funeral services of their fellows. Wardens were elected to manage the fraternity with four meetings a year to discuss fraternity business. Wealthy merchants rarely joined these community enterprises and in London such fraternities, a form of corporate chantry, co-existed alongside the privately funded chantries of the aldermanic elite. The brotherhood of St. James enjoyed particular popularity amongst the joiners who lived in the parish: many became members. One wealthy joiner, William Whitman (d. 1421), left a property to the fraternity which may have served as their hall.28 It is not until 1454 that we learn of a second fraternity, for Our Blessed Lady, also at St. James. William Forest, a barber, left five torches weighing five pounds in total to this second brotherhood.29 The fraternity of Our Lady came to enjoy noteworthy popularity during the latter half of the fifteenth century, with a further thirteen bequests made in the wills of parishioners who were presumably members.30 In the same period, there were eight bequests to the fraternity of St. James, the last of which was made by the pewterer Peter Bishop in 1480.31 The foundation of these two communal chantries added another liturgical layer to an evolving commemorative infrastructure of auxiliary priests benefiting the parish community. By the time of the 1548 chantry certificates St. James Garlickhithe, with 400 parishioners, seemed much like other wealthy London parishes.32 It had enjoyed generations of bequests from its parishioners, many of whom were members of the parish fraternities. Others had paid for the rebuilding of the fabric of the church with chantry endowments set up for the good of their souls. What, therefore, was exceptional about this parish and attracted Kent’s attention?

Merchant Chantries

Perpetual chantries in St. James Garlickhithe were richly endowed by the merchant ‘heavy-weights’ of the parish. The wealthy vintner, John de Oxenford (d. 1342), was the earliest benefactor to set out the terms of a chantry foundation in St. James.33 But three of his four executors died in quick succession before the final arrangements could be made. Richard Rothing died in 1346 (his will has not survived) but two other executors, the chaplain John Whithorn de Dounton (d. 1349) and the corn dealer Walter Neel (d. 1353), left instructions in their own wills to complete the Oxenford foundation.34 From Whithorn’s will we learn that the chantry was to be served by three perpetual chaplains who were to celebrate daily the Placebo and Dirige and De Profundis, recited after compline, and that this was to take place at Oxenford’s tomb. This monument, where the Offices of the Dead were to be daily recited for the benefit of Oxenford’s soul, thus had a role to play in the celebration of divine service. It is unclear why the surviving executor, the fishmonger and city alderman Adam Brabazon (d. 1367), failed to complete the endowment, and the eventual foundation was not completed until 1446. On 8 February the then rector of St. James, William Huntingdon, and his two churchwardens finally received letters patent granting them the tenements and property to endow the ‘Oxenford Chantry’. The parish had not forgotten their rights and Huntingdon’s successful campaign to restore this foundation enabled, at long last, two priests to celebrate for the benefactor’s soul.35 Further letters patent were granted confirming the arrangements in 1456 and in 1466.36 In 1548 the Oxenford endowment provided an annual return of £17 15s and funded one priest at an annual salary of £8 13s 4d for Oxenford’s obit and alms to the poor. There was a surplus of £9 1s 8d for the parish.37 The property was evidently of some value, which probably accounts for the difficulties the parish experienced in obtaining ownership.

It was in 1376 that the earliest (successful) foundation was made when John Rothing devised a portfolio of property and rents within the city of London to the rector and churchwardens of St. James who were to endow a chaplain to celebrate for his soul. This chaplain was to receive an annual stipend of £8 and any surplus income from the property was to be used, as was the custom, for repair and the maintenance of the property. In 1548 this endowment was valued at £22 12s p.a. providing an annual salary of £8 to the chaplain George Strowgar with a further £2 spent on the quit-rent to the king, payment of the costs of Rothing’s obit and alms to the poor. There was a balance of £12 12s for the parish.38 Rothing had also left a further £60 for three other chaplains to pray for his soul for three years after his death. A fifth chaplain was to be employed to perform Rothing’s anniversary, for which service this rich vintner left £20.39 Three years after Rothing’s death there were seven chaplains serving at St. James, namely John Barrow, Roger Hunte, William Lude, John Say, John Somerwell, John Wodeford and William Wylton.40 Rothing’s will is silent on what intercessory services were to be performed at his grave but it is noteworthy that he had specifically set out his place of burial, with his exhumed parents, within the belfry and at the western entrance to the church. They were hardly likely to be forgotten by visitors and parishioners to St. James.

It is striking that within five years of Rothing’s endowment another influential parishioner from St. James, the controversial royal financier and merchant Richard Lyons, used some of his spectacular (if ill-gotten) wealth to secure his own intercession. His endowment was to be served by a further six chaplains.41 By 1381 this placed St. James within the top five city churches which could boast eleven or more ancillary chaplains.42 Lyons intended that his six chantry chaplains were to serve at an altar set on a raised platform before the rood for which Lyons left a further £100:43 it is possible that this was the St. Katherine altar referred to in later wills.44 But the lawsuit brought by Lyons’ ex-wife, Isabella Pledour, led to delays in settling his estate, and the acquisition of much of the Lyons property by the royal princes, Edmund of Langley and Thomas of Woodstock, further complicated the executors’ task.45 By the time Thomas Lincoln, a wealthy draper living in the parish, came to establish his own perpetual chantry in St. James in 1417, the Lyons’ chantry was in financial difficulties; as a result Lincoln took the opportunity of amalgamating this with his own.46 Whether the delays during probate had prevented the completion of Lyons’ foundation, or whether Lincoln may have acted on behalf of Gilbert Bonyet (Lyons’ principal executor), who had died in 1398, is unclear.47 Nonetheless, in 1548 the endowment of the Lyons/Lincoln chantry was valued at £22 8d of which £8 supported the annual salary of the chaplain John Barret and, after subtracting other costs and charges, the parish received a surplus of some £8 13s 4d.48

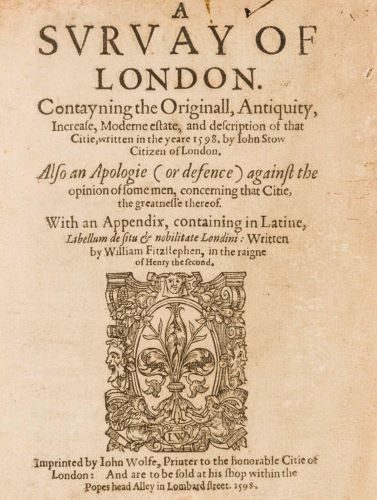

Richard Lyons not only set out to endow a chantry he also furnished the altar: from the 1449 inventory of the parish goods, for example, we learn of a silk vestment embroidered with his rebus (lions) which he had given to the church.49 Further, Lyons paid for two newly painted figures of Our Lady and St. John the Baptist which were to be placed on the rood-beam within the church. It was here, at the entrance to the chancel, where Lyons requested burial and where fifty torches were to burn around his body on the day of his burial. Lyons also directed that eight torches were to burn during the anniversary marking his death.50 Lyons, like Rothing, was making sure he benefited from a public grave, to be set in a prestigious part of the church, and with appropriate funeral and anniversary rites. Lyons did not refer to his monument in his will but John Stow saw it in 1598:

His picture on his gravestone very fair and large, is with his hair rounded by his ears, and curled, a little beard forked, a gown girt to him down to his feet, of branched Damaske wrought with the likenes of flower, a large pursse on his right side, hanging in a belt from his left shoulder, a plaine whoode about his necke, covering his shouldes, and hanging backe behinde him.51

Stow rarely described the appearance of any funerary monuments in his Survey of London, so he had evidently been impressed by this particular survival. The ‘picture on his gravestone’ can be nothing other than a commemorative brass and probably caught Stow’s eye because it had been imported from overseas: the patterning described on the gown was unusual amongst English brasses of the late fourteenth century but more common on Flemish compositions.52 Stow did not record the Lyons inscription but part of this was later noted in the seventeenth century by John Weever:

Gemmarius Lion hic Richardus est tumulatus;

Qui fuit in rabie vulgi (ve) decapitatus.

Hic bonus extiterat cunctus [cunctis]; hospes egenorum;

Pacis et auchor [auctor] erat, dilector et urbis honorum.

Anno milleno tricentene numerato

Sic octogeno currente cum simul uno,

Plebe rea perii[t]… Morte dolosa.

Basily festo dum regnat plebs furiosa.53[Richard Lyon, a jeweller,54 is buried here

Who was beheaded during the raging of the mob.

He was noted as being good to everyone, welcoming the poor

And he was a peace-maker, and fond of the honours of the City.

In the year reckoned as 1,000, and 300

And 80 running along with one

He perished through the people’s fault … by a doleful death

On the feast of St. Basil [14 June], while the mad people were in control]

The incomplete text, with some errors, copied down by Weever suggests this was taken from a marginal inscription placed around the Lyons effigy. The reference to Lyons’ murder shows that it was his executors, the vintner Gilbert Bonyet, John Tyso, rector of Drinksone (Suffolk), Robert Payne, rector of Layer Breton (Essex) and the London pepperer John Warde, who were the patrons of this epitaph and who chose to mark the violence of his death by recording it on the brass inscription, perhaps because he had died unshriven. So from Stow’s description, the text of the epitaph and the instructions given by Lyons about his funeral and his desired obsequies before the rood, we learn that this rich alien merchant was to be remembered by an impressive and eye-catching monument of some magnificence in one of the most prestigious locations in the church.55 For the brass to be commissioned and brought from overseas demonstrates the lengths to which the very wealthy could go in order to have a distinctive and bespoke tomb marking their burial site. But it is of particular interest that Lyons wanted his chantry service to be celebrated where he was buried, before the rood.

The importance of the monument during the funeral and anniversary service is not confined to the Oxenford and Lyons examples. In his own will of 1417 Thomas Lincoln directed that two torches were to burn, one at his head and the other at his feet, during his exequies. Two torches were also to burn in the same places during his annual obit.56 The wording of the will is ambiguous and does not specify that the torches were to burn at the head and feet of his monument but for this to be successfully achieved a form of grave marker was needed. The functional role of such grave monuments is also evident in other London parish churches: at St. Mary at Hill, for example, the tomb of the grocer William Cambridge (d. 1431) was to be the centre-piece for a procession by every priest, child and clerk at Evensong on Christmas Day, each of whom was to hold a candle and to sing a respond of St. Stephen, followed by a versicle with the collect of St. Stephen.57 For St. James Garlickhithe, we can be more certain of similar arrangements organized by Nicholas Kent (d. 1467), another vintner who was later ordained priest. His original will has not survived but it was copied into the Vintners’ ‘Ordinance Book’.58 In this Kent described the anniversary that was to be celebrated for William Scarborough, a former master of the Vintners’ Company, on every 30 December ‘for quicke and deade memorie masses’. The terms included a Placebo and Dirige on the eve of the anniversary followed by Requiem ‘by note’ and with the ringing of bells. But perhaps most significantly of all, Kent specifically instructed that two tapers were to burn ‘aboute the Tombe of the saide Willm Scarburgh in the tyme of the saide Exequies’. Scarborough’s monument, like those of Oxenford and Lyons a century before – and probably Lincoln’s also – was to play an important part during their commemorative celebrations within St. James.

Commemoration at St. James Garlickhithe took many different forms. The inventory of the church goods, written by the rector William Huntingdon in 1449, reveals a substantial collection of vestments, altar cloths, mass books, antiphonals, breviaries, chalices, monstrances and plate representing generations of gift-giving by parishioners.59 A number of items bore the arms, mark or initials of the donor: the arms of Robert Chichele and his wife Elizabeth More, for example, were embroidered on the towels, vestments and altar cloths given by them to the parish.60 But of some interest were the books owned by St. James Garlickhithe and which formed an impressive collection.61 In total there were forty-one books recorded in the inventory. Other city of London parishes had comparable but smaller libraries, the exception being St. Margaret Bridge Street where in 1472 fifty-nine books were recorded by the churchwarden Hugh Hunt.62 Parish inventories from elsewhere in London had smaller collections; thirty-three were recorded in the inventories from St. Peter Cheap (1431), St. Nicholas Shambles (1457) and St. Stephen Coleman Street (1466)63 and slightly fewer – thirty – referred to in the 1470 inventory for St. Margaret Pattens.64 For St. James Garlickhithe the titles of nine books were accompanied by the names of their donors recorded against their entry in the inventory.65 One such gift was the missal given by Gilbert Bonyet to the altar of St. John the Baptist and valued at £8; Alice King, widow of the draper and alderman William, had given another missal worth £4 to Our Lady altar. In his will of 1393, William King had himself bequeathed his bible, written in French, to the parish and also his copy of Liber Regalis, also in French. He gave instructions that these were to be chained inside St. James’ in the same way as a bible was chained before an image of Our Lady in St. Paul’s Cathedral. King’s intention was that these should be publicly available and that they could be read by parishioners and visitors alike in return for prayers for his soul, his parents’ soul and that of Robert Luton.66 From the inventory we learn that this French bible was still in use, that it was chained, as instructed, and valued at 40d: the relatively low value suggests considerable wear and tear during the intervening fifty years.67 There were also four antiphonals and four organ books given by former parishioners and by chaplains: an antiphonal ‘on the parson’s side’ (presumably used in the chancel) was described as ‘Portyngdon’s gift’. Thomas Portington (d. 1443), was a chaplain at St. James, who bequeathed an antiphonal to the church in his will which was valued at 100s in the inventory.68 This mid fifteenth-century parish library was valued in total at £154 11s 4d with comparably more liturgical and devotional books, polyphonies, song and organ books than other London parishes.69 Merchant benefaction had endowed seven perpetual chantries at St. James Garlickhithe and provided an important library from which we learn of music in the parish, of at least one organ – perhaps two – and with divine services sung ‘by note’, probably by the chaplains themselves. Moreover it is clear that these city merchants and their executors gave to the benefactors’ tombs a central role in the commemorative services.

William Huntingdon: De Facto ‘Master’ of the Parish

William Huntingdon was the bastard son of John Holland, earl of Huntingdon (1388) later duke of Exeter (1397), the half-brother of Richard II.70 This illegitimate royal kinsman was rector of St. James Garlickhithe from as early as 1407, when he was witness to the will of the vintner Henry Mitchell, until his death in 1455.71 The advowson of St. James was held by Westminster Abbey and it was during the abbacy of William of Colchester (1386–1420) – a supporter of Richard II – that Huntingdon was appointed incumbent. It was probably young William’s kinship to Richard which led to his appointment as rector of St. James a position he held for almost fifty years. His will contains a number of conventional bequests for the benefit of his soul, including 6s 8d to each of the parish priests and 3s 4dto each clerk to sing for his soul between the day of his death and at his month’s mind. The sum of two nobles (i.e. 13s 4d) was to be kept by one of his executors John Raymond to pay for Huntingdon’s daily mass in St. James’ which was to be celebrated for one year after his decease. He also bequeathed to the parish vestments and a hearse cloth for the poor and it is in Huntingdon’s will that we learn of the parish Bede Roll – where he specifically asked to be included. There are few references to him in the wills of his parishioners and he was only occasionally called upon to be a witness, or serve as executor or supervisor of a will. Two notable exceptions were his appointment as supervisor to the wills of the chaplain Thomas Portyngton and William Clench parish clerk of St. James (d. 1445).72 Huntingdon might be considered as a disengaged incumbent but as we have already seen from his actions in 1446, this was not the case. The restoration of the ‘Oxenford Chantry’ was not the only occasion when the rector intervened to protect the rights of the parish. Ten years earlier, in 1436, archbishop Henry Chichele (brother of merchant Robert, one of Huntingdon’s flock) was compelled to intercede and resolve a long running dispute. This quarrel, between Huntingdon and his churchwardens at St. James, with their counterparts at St. Martin Vintry, concerned the location of the anniversary for the vintner William Hervy (d. before 1436).73 The matter was resolved by the archbishop who directed that two chaplains were to celebrate mass in both these Vintry churches. Twelve years later it was Hervy’s executor, the vintner-priest Simon Adam (d. 1448), who completed the arrangements for the Hervy endowment in St. James Garlickhithe by setting out its terms. A portfolio of city property was enfeoffed to William Huntingdon and the churchwardens of the parish, John Hewett and John Stysede, to employ a chaplain to celebrate daily at the altar of St. Katherine. One of the existing parish chaplains, John Sherman, was appointed as the first celebrant and paid £7 a year.74 Huntingdon was evidently a man of charisma and influence who was prepared to intercede when necessary. He was almost certainly an associate with other like-minded movers and shakers amongst the London clergy such as John Neel, master of St. Thomas of Acre (1420–63) and John Wakeryng who served as master of the hospital of St. Bartholomew’s in West Smithfield (1423–66).75 An explanation of the surprising degree of authority exercised by Huntingdon may lie in his origins for his half-brother was the prominent Lancastrian, John Holland, duke of Exeter (d. 1447), appointed as admiral of England (1435) and king’s lieutenant of Aquitaine (1439).76 Holland served on the royal council during the 1440s and it is perhaps through his influence at court that his elder half-brother, the rector of a city church, was able to secure the sought-after Oxenford legacy.

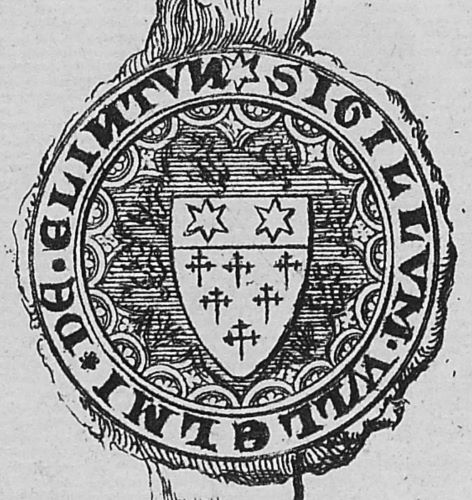

William Huntingdon died in 1455, having served as rector of St. James Garlickhithe for almost half a century. His long service in St. James Garlickhithe, the relationship with his parishioners and his role as champion for the parish interests in 1436 and 1446 – perhaps aided by his links to members of the royal council – suggest a strong personality backed up by flair and energy. Huntingdon worked hard, and with success, for the common good of the parish. By the time of his death in 1455, his many enterprises had left the parish with a rich liturgy, substantial lay investment in the parish both in terms of the infrastructure of the church building and with endowed property, and with church goods valued at £576. He was a de facto master of a college which, however, lacked formal statutes. Huntingdon’s successor as rector of St. James Garlickhithe was Thomas Saintjust who served for a little under two years before his resignation.77 On 31 May 1457 the royal councillor, Peter de Tastar (d. 1467), dean of Saint-Seurin in Bordeaux, and a Gascon by birth became the new incumbent.78 St. James Garlickhithe was one of a number of benefices which de Tastar enjoyed together with the prebendary of Leighton Buzzard. He was later appointed a canon of Lincoln Cathedral and in 1465 de Tastar (as Peter Tastour) was appointed as provost of Beverley. He resigned as rector of St. James Garlickhithe before October 1466. How active de Tastar was in the affairs of his London parish is unknown: he requested burial in St. James if he died in London, but only if he did not die in the house of the London Austin Friars, which was evidently his first choice. This suggests that de Tastar stayed in the Augustinian house when in the city of London.79 No monument was recorded for de Tastar in St. James. In his will de Tastar left £20 for repairs and ornamentation of the church but deducted the sum of £10 that the parish owed him for repairs he had paid for at the Oxenford chantry.80 The will suggests a man involved in, but somewhat distant from, parish affairs and it is this which may account for the disorganised state of the parish chaplains following the fifty-year stewardship of William Huntingdon. It was left to a parishioner, Thomas Kent, to set about organizing these priests who were serving St. James, as a result of the benefactions of generations of wealthy merchants. Kent provided them with one of his own tenements, adjacent to the church with a cloister attached;81 in his will he provided utensils for their use and a common chest containing £10 which was to be available as ready money and could be used as a loan whenever fuel and charcoal were to be bought.82 When his widow, Joan, died in 1487, she left her own bequest of £6 13s 4dto the commons of priests on condition that the commonalty of priests fulfilled her husband’s foundation.83 This ‘commons’ had grown organically: it had been paid for by the wealthy merchants of the parish, nurtured and defended by William Huntingdon and ordered and reorganised by Thomas Kent, one of the parish’s most active bureaucrats.

Merchant benefaction in St. James Garlickhithe provided a portfolio of city property used to endow a total of seven perpetual chantries, which were to aid their journey to ‘the Saints in Paradise’. These merchants and their executors went to some lengths to set out the terms of their foundations and the role the funerary monument was to play as an evocative prop in fulfilment of their obsequies and the celebration of the Offices of the Dead. Yet this city parish was also remarkable for its extensive library, which provided another dimension to the liturgy and the provision of ‘quicke and deade memorie masses’. This array of benefactions is rarely seen so clearly but St. James Garlickhithe has afforded a rare opportunity to witness these practices in some detail, and it allows us to see the extent to which certain parishes were especially popular foci for benefactions and commemoration. There is potential for further research on variations in commemorative practice across London’s churches and to consider other particular parish hot spots. For St. James Garlickhithe, the key to success was the actions of two men, the long stewardship of the incumbent William Huntingdon, and the reorganization of the chaplains by the royal administrator and parishioner Thomas Kent, which ensured the effective commemorative well-being of the living and the dead. In this church with ‘a cult of the living in the service of the dead’, the living worked hard to protect the rights of the dead in late medieval London.

Endnotes

- CPR 1476–85, p. 252. I thank Jonathan Mackman for his photographs of this document. Kent was one of a number of important parishioners. For his remarkable career, see the ODNB entry by R. Virgoe, ‘Kent, Thomas, b. in or before 1410, d. 1469’, and David Stocker’s recent essay, ‘Wool, cloth and politics 1430–1485: the case of the merchant stockers of Wyboston and London’, in The Medieval Merchant, ed. C. M. Barron and A. F. Sutton (Donington, 2014), pp. 127–45.

- London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate 1548, ed. C. J. Kitching (London Record Society, xvi, 1980), pp. 9–10.

- A. Crawford, A History of the Vintners’ Company (1977), pp. 42–3.

- For the parish in medieval London we are indebted to the work of Clive Burgess (see in particular his ‘Shaping the parish: St. Mary at Hill, London, in the fifteenth century’, in The Cloister and the World: Essays in Medieval History in Honour of Barbara Harvey, ed. J. Blair and B. Golding (2nd edn., Oxford, 2003), pp. 246–86; and ‘London parishioners in times of change: St. Andrew Hubbard, Eastcheap, c.1450–1570’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, liii (2002), 38–63, esp. pp. 46–52). Other studies include H. Combes, ‘Piety and belief in 15th-century London: an analysis of the 15th-century churchwardens’ inventory of St. Nicholas Shambles’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, xlviii (1997), 137–52. An innovative and insightful approach to mercantile commemoration practice is provided by D. Harry, ‘William Caxton and commemorative culture in medieval England’, in The Fifteenth Century XIII. Exploring the Evidence: Commemoration, Administration and the Economy, ed. L. Clark (Woodbridge, 2014), pp. 63–79.

- The wills for the vintners John Longe (d. 1363) and his son Roger (d. 1376) both direct their souls to ‘the Saints in Paradise’, the formulaic destination applied to such wills written in French (LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/090 (John Longe) and CLA/023/DW/01/103 (Roger Longe)).

- W. Durrant Cooper, ‘St. James Garlickhithe’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, iii (1871), 393–403, at p. 401; M. B. Honeybourne, A Short Account of the Church of St. James Garlickhythe, E.C. 4 (1924), pp. 3–4. It was through the garlic trade that the parish received its suffix (J. Stow, A Survey of London. Reprinted from the text of 1603, ed. C. L. Kingsford (2 vols., Oxford, 1908), i. 249–50). There has yet to be any comprehensive archaeological survey of the site.

- A. R. Myers, ‘The wealth of Richard Lyons’, in Essays in Medieval History Presented to Bertie Wilkinson, ed. T. A. Sandquist and M. R. Powicke (Toronto, 1969), pp. 301–29.

- C. Steer, ‘The Plantagenet in the parish: the burial of Richard III’s daughter in medieval London’, The Ricardian, xxiv (2014), 63–73.

- Kingsford, Survey of London, i. 249–50.

- J. Lutkin, ‘The London craft of joiners, 1200–1550’, Medieval Prosopography, xxv (2005), 129–65.

- Kingsford, Survey of London, i. 249–50. Merchants as patrons of parish benefaction, including church rebuilding, is a subject most recently discussed by C. Burgess, ‘Making Mammon serve God: merchant piety in later medieval England’, in Barron and Sutton, The Medieval Merchant, pp. 183–207.

- J. Schofield, ‘Saxon and medieval parish churches in the City of London: a review’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, xlv (1994), 23–146, at p. 76 (Table 1). The rebuilding of All Hallows the Less was noted by Stow in Kingsford, Survey of London, i. 235. Many city churches were either rebuilt or reconstructed during the 15th century’s ‘golden age of church rebuilding’.

- The wills are to be found in the Hustings (19 wills), Commissary (71) and Archdeaconry (1) courts of London and the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (23) and Lambeth court (1). The Vintners’ ‘Ordinance Book’ refers to two now lost wills for William Scarborough (d. c.1436–38) and Nicholas Kent (d. 1467), extracts from which were copied into this ‘Ordinance Book’, GL, MS 15364 fos. 53r–55r.

- The earliest reference to the rood is found in the will of Richard Lyons (d. 1381) (LMA, MS 9171/1, fos. 79v–80r).

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/104.

- LMA, MS 9151/1, fos. 13v–14r. I thank Robert Wood for this reference.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/144.

- LMA, MS 9171/3, fos. 114v–115r (Lady Chapel) and MS 9171/3, fo. 268v (south aisle).

- LMA, MS 9171/5, fo. 172r.

- E.g. the draper Richard Lincoln (d. 1369) (LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/97).

- E.g. Thomas Say, vintner (d. 1402) (LMA, MS 9171/2, fos. 19r–19v).

- The relationship of the chantry with other ‘pro anima’ arrangements is best summarised in C. Burgess, ‘Chantries in the parish, or “Through the Looking-glass”’, in The Medieval Chantry in England, ed. J. M. Luxford and J. McNeill (Leeds, 2011), pp. 100–29. Chantry endowments in other urban centres, notably at York, are discussed by R. B. Dobson, ‘The foundation of perpetual chantries by the citizens of medieval York’ in his collected essays, Church and Society in the Medieval North of England (1996), pp. 253–66. For London, see R. Hill, ‘“A Chaunterie for Souls”: London chantries in the reign of Richard II’, in The Reign of Richard II: Essays in Honour of May McKisack, ed. C. M. Barron and F. R. H. Du Boulay (1971), pp. 242–55 and more recently, M. Rousseau, Saving the Souls of Medieval London: Perpetual Chantries at St. Paul’s Cathedral, c.1200–1548 (Farnham, 2011), esp. ch. 1. For other case studies from medieval London, see J. Colson, ‘Local communities in fifteenth-century London: craft, parish and neighbourhood’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 2011).

- A. N. Galpern, ‘The legacy of late medieval religion in sixteenth-century Champagne’, in The Pursuit of Holiness in Late Medieval and Renaissance Religion, ed. C. Trinkaus and H. O. Oberman (Leiden, 1974), pp. 141–76 at p. 149.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/90.

- In 1378 Archbishop Sudbury capped the wage for stipendiary priests at 7 marks (£4 13s4d) per year, see Hill, p. 243.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/93.

- English Gilds, ed. L. Toulmin Smith and L. Bretano (2nd edn., Oxford, 1963), pp. 3–5. For these ‘communal chantries’ in medieval London, see C. M. Barron, ‘The parish fraternities of medieval London’, in The Church in Pre-Reformation Society: Essays in Honour of F .R .H. Du Boulay, ed. C. M. Barron and C. Harper-Bill (Woodbridge, 1985), pp. 13–37, esp. pp. 23–4. The St. James Fraternity is discussed further in C. M. Barron and L. Wright, ‘The London Middle English guild certificates of 1388–9’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, xxxix (1995), 108–45.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/149. The identification of the Whitman tenement as the future Joiners’ Hall was made by Lutkin in ‘London craft of joiners’, p. 144.

- LMA, MS 9171/5, fo. 134v.

- LMA, MS 9171/5, fo. 243r (John Trogan alias White, draper, 1458); MS 9171/6, fo. 22r (John Freeman, joiner, 1468); TNA: PRO, PROB 11/5, fos. 246r–246v (Thomas Saunder, brewer, 1470); LMA, MS 9171/6, fo. 89r (Thomas Quinn, fishmonger, 1471), fos. 146v–147r (John Woodruff, joiner, 1473), fo. 191v (John Shidborough, yeoman, 1476) and fos. 370v–371r (Margaret Clapham, widow of William Chapman a woodmonger, 1484); MS 9171/7, fo. 5v (John Wavell, joiner, 1486) and fos. 96v–98v (Joan Kent, widow of Thomas Kent, clerk of the king’s council, 1487); TNA: PRO, PROB, 11/9, fos. 212r–212v (Thomas Staunton, tallowchandler, 1492); LMA, MS 9171/8, fo. 70r (John Elliot, chaplain, 1494), fos. 88v–89r (John Slater, chaplain, 1495) and TNA: PRO, PROB 11/11 fos. 88v–89r (Marion Staunton, widow of Thomas, 1497).

- LMA, MS 9171/5, fos. 192v–193r (Peter Hoke, joiner, 1456), fo. 259v (Henry Sweatman, joiner, 1458); MS 9171/6, fo. 22r (John Freeman, joiner, 1468), fo. 89r (Thomas Quinn, fishmonger, 1471), fo. 179r (Robert Smith alias Arnold, joiner, 1475); TNA: PRO, PROB 11/6, fos. 164v–166v (Joan Bromer, widow, 1476); LMA, MS 9171/6, fo. 191v (John Shidborough, yeoman, 1476) and fo. 326v (Peter Bishop, pewterer, 1480). Freeman, Quinn and Shidborough were the only testators who left bequests to both fraternities.

- Kitching, London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate, pp. 9–10.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/69.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/77 (Whithorn) and CLA/023/DW/01/81 (Neel).

- CPR 1441–6, p. 425.

- CPR 1452–61, p. 292 and CPR1461–7, p. 462.

- Kitching, London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate, p. 9.

- Kitching, London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate, p. 9.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/104.

- The Church in London 1375–1392, ed. A. K. McHardy (London Record Society, xiii, 1977), p. 8. There were few parishes which had more than seven chaplains. The wealthy mercer parish of St. Lawrence Jewry had, for example, as many as 16 with 10 each in St. Michael Cornhill and St. Christopher (McHardy, pp. 8–9). The average number of extra priests in the city of London in 1379 was four per parish.

- For his biography, see R. L. Axworthy, ‘Lyons, Richard (d. 1381)’, ODNB (although the reference to Lyons’ burial in St. Martin Vintry is incorrect) and Crawford, A History of the Vintners Company, pp. 49–53.

- The other parishes were St. Lawrence Jewry (16), St. Bride (14), St. Antonin (12) and St. Magnus and St. Nicholas Cole Abbey (11 each) (McHardy, pp. 8–9).

- LMA, MS 9151/1, fos. 79v–80r.

- E.g. the chaplain, John Penny (d. 1431) (LMA, MS 9171/3, fo. 263v).

- Calendar of Plea and Memoranda Rolls, ed. A. H. Thomas and P. E. Jones (6 vols., Cambridge, 1926–61), iii. 151–3 and 184–5. For the royal princes, see the Lyons ODNB article, n. 41 above.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/144; Kitching, London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate, p. 9.

- Bonyet’s will has not survived although we learn from Stow’s reference to his monument that Bonyet was buried in St. James Garlickhithe (Kingsford, Survey of London, i. 249).

- Kitching, London and Middlesex Chantry Certificate, p. 9.

- Westminster Abbey Muniments (hereafter WAM), MS 6644. I am grateful to Matthew Payne, Keeper of the Muniments, for his discussion of this manuscript.

- LMA, MS 9151/1, fos. 79v–80r.

- Kingsford, Survey of London, i. 249.

- N. Rogers, ‘The lost brass of Richard Lyons’, Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society, xiii (1982), 232–6. For the import of these expensive overseas memorials to an English market, see P. Cockerham, ‘Hanseatic merchant memorials: individual monuments or collective “memoria”’, in Barron and Sutton, The Medieval Merchant, pp. 392–413, at pp. 393–400.

- J. Weever, Ancient Funeral Monuments (1631), pp. 406–7. I thank Jerome Bertram for his discussion on the Lyons epitaph.

- It was not unusual for London merchants to trade in multiple goods and Lyons evidently also dealt with precious stones.

- For the importance of burial before the rood, see R. Marks, ‘To the honor and pleasure of almighty God, and to the comfort of the parishioners: the rood and remembrance’, in R. Marks, Studies in the Art and Imagery of the Middle Ages (2012), pp. 798–814.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/144.

- The Medieval Records of a London City Church (St. Mary at Hill) A.D. 1420–1559, ed. H. Littlehales (2nd edn., Woodbridge, 2002), p. 16; see also Burgess, ‘Shaping the parish’, p. 280. Cambridge did not refer to this procession in his will and it is from a note made in 1486, when the will was copied into the churchwardens’ accounts, that we learn of this annual procession to the tomb.

- GL, MS 15364, fos. 53r–55r. I am grateful to Graham Javes for alerting me to this reference. No relationship has yet been found between Nicholas Kent and his neighbouring parishioner of the same name, Thomas, who died in 1469. William Scarborough’s will is also now lost.

- WAM, MS 6644. I am grateful to Clive Burgess for providing me with a copy of his transcript. The 1449 inventory is the only known record of church goods from this particular city church as the 1552 return has not survived (H. B. Walters, London Churches at the Reformation (1939), p. 20).

- WAM, MS 6644.

- For books in London parishes, see F. Kisby, ‘Books in London parish churches before 1603: some preliminary observations’, in The Church and Learning in Later Medieval Society: Essays in Honour of R. B. Dobson, ed. C. M. Barron and J. Stratford (Donington, 2002), pp. 305–26.

- P. R. Robinson, ‘A “Prik of conscience cheyned”: the parish library of St. Margaret’s, New Fish Street, London, 1472’, in The Medieval Book and a Modern Collector: Essays in Honour of Toshiyuki Takamiya, ed. T. Matsuda, R. A. Linenthal and J. Scahill (Cambridge, 2004), pp. 209–21, at pp. 219–21.

- Combes, ‘Piety and belief ’, p. 138.

- W. H. St. John Hope, ‘Ancient inventories of goods belonging to the parish church of St. Margaret Pattens in the city of London’, Archaeological Journal, xlii (1885), 312–30, at pp. 314–15.

- We do not know if the names of the donors were recorded within the book or on a nearby board or table so that the readers knew who to pray for. Their names would certainly have been recorded in the Bede Roll. None of the books survive.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/123.

- Robinson has suggested that King’s gift of a French bible was to benefit transient parishioners from overseas (Robinson, ‘A “Prik of conscience cheyned”’, p. 212).

- LMA, MS 9171/4, fos. 128r–128v.

- The books of music are discussed further in C. Burgess and A. Wathey, ‘Mapping the soundscape: church music in English towns, 1450–1550’, Early Music History, xix (2000), 1–46.

- A. B. Emden, A Biographical Register of the University of Cambridge to A.D. 1500, (Cambridge, 1963), p. 322.

- LMA, MS 9171/1, fo. 176v. Huntingdon was ordained sub-deacon on 18 Dec. 1406, deacon on 19 Feb. 1407 and priest on 21 May in the same year (V. Davis, Clergy in London in the Late Middle Ages: a Register of Clergy Ordained in the Diocese of London Based on Episcopal Ordination Lists 1361–1539 (2000)).

- LMA, MS 9171/4, fos. 128r–128v (Portyngton) and fo. 160r (Clench).

- Discussed in G. Javes, ‘Priests in the Vintners’ Company in the 15th century’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, xli (2010), 191–5.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/177.

- John Neel was a man of some influence (see A. F. Sutton, ‘The hospital of St. Thomas of Acre of London: the search for patronage, liturgical improvements, and a school under Master John Neel, 1420–63’, in The Late Medieval English College and its Context, ed. C. Burgess and M. Heale (Woodbridge, 2008), pp. 199–229). Huntingdon, with John Carpenter and Thomas Chattesworth, entered into a 98-year lease of a property in All Hallows Thames Street with Wakeryng and the brethren of St. Bartholomew’s in 1439 (Calendar of Plea and Memoranda Rolls, ed. Thomas and Jones, v. 14–5).

- For John Holland, duke of Exeter, see R. A. Griffiths, ‘Holland [Holand], John, first duke of Exeter (1395–1447)’, ODNB.

- G. Hennessy, Novum Repertorium Ecclesiasticum Parochiale Londinense (1898), p. 248.

- For de Tastar, see Javes, pp. 193–4.

- The Austin Friars was a popular place of burial for aliens, especially Italians.

- TNA: PRO, PROB 11/5, fos. 151r–151v.

- Cooper, ‘St. James Garlickhithe’, p. 401.

- TNA: PRO, PROB 11/5, fos. 205r–206r.

- TNA: PRO, PROB 11/9, fos. 112r–113v and also LMA, MS 9171/7, fos. 96v–98v.

Chapter 4 (71-89) from Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, edited by Martin Allen and Matthew Davies (Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 06.30.2016), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons