Investigating medieval merchants and their individual connections to the military.

By Dr. Sam Gibbs

Faculty Business Manager

King’s College London

By Dr. Adrian R. Bell

Research Dean, Prosperity and Resilience

ICMA Centre Henley Business School

University of Reading

The interplay between mercantile and military activity is a complex one. Often warfare is portrayed as having a negative impact on trade, due to the breakdown of civilian law and order, raiding, piracy and even conscription of ships and seizure of goods. Despite these issues, there are potential opportunities for profit in conflict: the increased demand for military supplies, and the potential for providing them to an array of garrisons, armies and fleets could provide an enterprising individual with an opening.1 Of course it was in the interest of military commanders to ensure that their soldiers had ready access to supplies of food and materials, and there were large-scale depots of military equipment, for example sheaves of arrows, notably in the Tower of London. Despite this provision there was a certain expectation that English soldiers were to be self-reliant. The limitations of central governance suggest that there was a place for private enterprise in the supply of English armies, in a similar manner to the indenture system, which was employed to raise the armies in the first place.

This chapter aims to investigate merchants and their individual connections to the English military, in the context of supply and personal military service. This will provide a clearer picture of both the victualling situation and how warfare could impact on an occupational group. This work will draw upon two main resources, the online databases produced by the ‘Soldier in later medieval England’ project,2 and the recently completed ‘Poll tax database’.3 Taken together these resources provide access to a variety of nominal sources, including muster rolls, letters of protection, appointments of attorney, and poll tax returns. These can be used to identify and analyse individual English merchants and their links to the military.

There is a large body of literature that considers trade and mercantile activity in the late medieval period, notably that of the English wool and cloth trade, due to its importance to royal tax revenues and the documentation that this generated.4 However, Goldberg suggests that this may be a distortion:

the historian of the medieval English economy is not overburdened with evidence. It follows that such sources as are available may assume an exaggerated importance. Thus overseas trade, and in particular the cloth trade, whose fortunes are known from the enrolled customs accounts, is allowed a degree of significance in terms of the national economy that has never been fully justified.5

There has been some discussion of the effects of warfare on trade and the economy.6 However, these studies have approached the topic top-down, considering the impact on the market and government over the impact on the individual.

There is less of a gap in the military historiography, which has focussed recently on the individuals within armies, considering and illuminating individual careers in arms. Of course, again due to the evidential base, this has tended to concentrate on those towards the top of the social scale; however, some studies have shown that it is possible to consider certain groups outside the social and military elite.7 Furthermore, recent work considering the maritime element of the Anglo-French wars has shown that it is possible to investigate a loose group of individuals that are unified to an extent by their occupations.8

The poll taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381 have provided a large proportion of the data analysed in this chapter. Despite the vast amount of raw data contained within the returns – 264,350 names – until relatively recently it has been largely ignored for historical research. Even studies concerned with demography, such as Thrupp’s The Merchant Class of Medieval London, are dismissive of the returns, asserting that ‘The schedule is so faulty that it cannot represent anything more than a preliminary survey; if the collectors had proceeded on this basis, they would have touched barely half their final total.’9 There has, however, been something of a rehabilitation of the poll tax returns as a source, notably Fenwick’s unpublished PhD thesis.10 Fenwick thoroughly deals with the various aspects of the returns, introducing the events and socio-economic changes behind their imposition, detailing the methods of collection, and discussing the other documentary sources connected to the returns, as well as evaluating the returns as a source and how they can be used effectively. Fenwick makes a cautious yet comprehensive case for the use of the returns; she proposes that many factors which should impact on the assessment of the returns have been overlooked, notably careful reading of the rules of collection and the effects of exemptions on the tax base, stressing that the boundaries between tax evasion and tax exemption were nebulous.11 Other historians have also considered the uses for the returns. Goldberg’s work on the demographics of York have shown how the returns can be used for smaller-scale case studies, and he strengthens the case for their use as an important historical source.12 Unfortunately, there is minimal literature concerned with the returns themselves. They have been utilized in other publications, especially those concerned with women’s history, as they are one of the few sources that record any details about women outside of the nobility. There are also two case studies: the first, dealing with New Romney in Kent, examines the returns as a source for the town’s social structure.13 The second considers the demographic structure of the county of Buckinghamshire at the time of the poll taxes.14 Of more direct relevance to this present research is a further study on the origins of English archers, which considers the use of the poll taxes when identifying archers in detail and the evidentiary issues surrounding this usage.15 Therefore, and despite the importance of the returns to this chapter, there is not an established methodology for the use of the returns, beyond the focused paper by Goldberg which gives an indication of the type of data that can be extracted.

At this stage it is worth discussing the sources further, in the context of the method employed in this chapter. The muster rolls are administrative documents created as a part of the indenture system, which by the late fourteenth century had almost wholly replaced previous methods of raising soldiers for the English crown. Instead of being based on any obligations due from land tenure, the indenture system relied on individual captains agreeing to provide a certain number of soldiers, for a certain period of time, in exchange for a predetermined amount of wages. Often a bonus, or regard, was included as well.16 The muster rolls are the records of exchequer officials certifying that the retinue captains had indeed arrived for the contracted service with the correct number and quality of soldiers. This process has yielded vast amounts of nominal data, concerning individuals of low socio-economic rank who would not often appear in other sources. The musters not only contain the names of those who fought, but also record how the army was divided into different retinues, and how these were further divided into men-at-arms and archers. Aside from these military ranks, they can also provide information on social position, troop movements, promotions, replacements and mortality rates.17

The nominal evidence provided by letters of protections and appointments of attorney can be considered alongside the muster rolls, and although they are not purely military in function they do have a close connection. Issued to ensure that an individual’s estates and property could not be claimed by legal process while their owner was abroad, they were often taken by soldiers who wanted to make sure that they would not fall victim to unscrupulous rivals while they were campaigning, particularly overseas. The protections and attorneys can contain residency and occupational data, crucial when considering an occupational group such as merchants. Some factors must be considered when using this evidence, however. Although these documents were theoretically available to any man who was able to seek the king’s justice, they were only of use to those who had property worth protecting. This means that the bulk of the soldiers going abroad did not bother to obtain them, as the majority did not possess the estates and landholdings that would make their acquisition worthwhile. Furthermore, there are other reasons why someone might be travelling outside England, unrelated to warfare, although this could include, rather pertinently for this chapter, trade.18

Although often nominal in form, the poll tax returns provide a very different set of data. They are organized by place of residency, through county, hundred and vill, and are inconsistent in organization between the different areas, possibly due to scribal whim in recording the required information. It has been suggested that the poll tax was an attempt to spread the burden of taxation onto a wider base throughout England, stemming from the economic issues resulting from the Black Death: ‘The Commons’ aim in imposing the poll taxes was to ensure that all, high or low, normally exempt or not, who could pay the tax did so … their aim was simply to relieve themselves of the main burden of tax’.19 Previously, taxation had been based on the fifteenth and tenth, a tax on the movable property of individuals throughout the realm. This meant that an individual could be assessed in several different locations where they held property and incur a high bill as a result. By shifting the basis of taxation to a per capita basis, more individuals were brought into the ‘national’ tax system.

Despite all being poll taxes, the three collections did vary significantly, when determining liability and the amount due. For example, a flat rate of 4d was due from every person over fourteen in 1377; however, the 1379 collection raised the age to sixteen and excluded married women. This indicates that some of the criticisms, particularly those of demographic imbalance, levied at the returns can be justified, as in 1379 there was no requirement to record wives, as they were not liable, and in 1377 nominal records were not required at all, although they have survived in several places, totalling 24,211 entries. However, it must be remembered that the returns were never intended to be a census of the realm, and that while caution must be taken when using them, the data contained in the returns is invaluable, as it is one of the few large nominal records extant for the medieval period and gives indications of wealth, status and, importantly for this chapter, occupations.

It has been shown by several historians that it is possible to reconstruct quite sophisticated career biographies of soldiers at the lower end of the social scale. Andrew Ayton uses the example of Norwich’s 1337 retinue to Gascony to demonstrate how men can be traced. He identifies up to a dozen men who were veterans of the Scottish wars, and a few who had fought in the War of St. Sardos.20 It is even possible to outline the careers of individual archers, as Simpkin does in his biography of Robert de Fishlake. This is however an exceptional circumstance, where the individual in question had given a lengthy testimony in the Hastings/Grey court of chivalry case. In his testimony Fishlake asserts that he has served in Scotland and France, as well as in the Mediterranean and Jerusalem. It is not possible to confirm all of this service, particularly in the Latin east, as this lay outside the purview of the exchequer. However it is possible to confirm some of his service, the earliest of which is Fishlake’s participation in the earl of Buckingham’s 1380 expedition to Brittany.21 For most archers however, the surviving evidence is not so complete, and this is where the prosopographical approach can be used.

These examples show that career reconstructions can be attempted, and that nominal linkage of records can be used to great effect. Despite this, however, it is clear that there is an evidentiary issue regarding the identification of individual persons and tracing careers. The gaps in the evidence base are a further hindrance, aggravated by the relatively low social status of the men in question. Therefore a certain number of assumptions must be made, and applied to the data gathered in the form of probabilities. However, many of these issues have been considered in depth before, and careful analysis can render informative and relevant conclusions.

The establishment of data criteria enables such studies to join together various nominal records. Similar processes have already been applied in other works.22 The first piece of information to be considered is the name. Spellings of both first and last names can vary greatly. However, by considering the phonetics of the name matches can be made. For example, John Smyth and John Smith are phonetically similar. Therefore, these spellings could also be considered the same man for the purposes of this research. Secondly, the chronological range of the campaigns will be considered. Here it is difficult to set an exact rule; instead a range of probabilities will be considered, and the further apart names appear in the records, the less likely it is to be the same individual. Of course certain names will occur more frequently in the records, which decreases their potential usefulness. In contrast, repeat occurrences of less common names provide stronger nominal links between data points.23 The example above of John Smyth/Smith is not a strong association, whereas a more unusual name, such as William Somerton/Somertom would be. A final check that must be made is the rank that each man holds in each muster. It would be unusual for a man serving as an archer to have served previously as a man-at-arms. Such a move would be an effective demotion. However, though rare it was not unheard of for a man to move downwards in this manner, possibly to take advantage of a favourable military posting.24 There is more evidence for promotions, and it appears that it was not uncommon for archers and men-at-arms to be drawn from the same families. Indeed, archers’ social status was not clear cut, and there were many Cheshire archers whose social standing in the county was comparable to that of men-at-arms.25 Therefore, a great deal of latitude must be given for changes in military status when linking the nominal records, both military and civilian. By using the criteria in this way, some probability groups can be established, with those identifications most likely to be correct separated from the least likely.

This nominal linkage approach can be used further by linking the military data to civilian taxation. This requires the use of other sources to effectively join the two, in this case the landholdings of retinue captains. Although the indenture system had encouraged men from outside the highest strata of society to lead retinues, on the whole captains were still men of property and estate and can be viewed as ‘gentleman careerists’ rather than as a fully professional soldiery.26 This means that records of where they held land are extant and can be traced in, for example, the inquisitions post-mortem. By identifying the vills in the poll taxes as lands which can be associated with retinue captains a link between the two data sets can be established. Although this is of more direct use when considering patterns of service and obligations, it does indicate that there is a strong reason to compare the two sets.

As previously mentioned, the language of the documents, particularly spelling, needs to be considered. Translation and grammar do not pose a problem, as the majority of the evidence is taken from documents in list form. However, medieval spelling could be problematic, especially when undertaking nominal record linkage. An example of this can be found via the medieval soldier online database for the records from the 1387 naval expedition under the command of the earl of Arundel. Here there are two documents, E 101/40/33, a retinue list written prior to the official muster and E 101/40/34, which is the actual muster itself. This therefore makes it highly probable that two men with the same name were the same person. In the first document there is an archer ‘Nicholas Scherley’ listed in the retinue of Sir Thomas Trivet, who appears in the muster as ‘Nicholas Sherley’ again in Trivet’s retinue, indicating how a nominal form could change depending upon the scribe who recorded it.27 It is common for men’s names to change form due to a variety of factors, including scribal whim and style. Phonetic influences are also apparent and can be clearly seen in the Welsh names recorded in musters. For example, patronymic names where ‘ap’ or ‘ab’ have been used could be conjoined to the following name giving us ‘such scribal delights as “aptharadur”’.28 Furthermore, the same name may appear in several forms, although commonly a scribe would only use one option throughout a document. For example, the forename Ieuan can be variably rendered as John, Jenkyn, Johannes and Yeuan.29 It is also possible that the men had described themselves differently and that the toponymic, patronymic and occupational surnames given in one document could be recorded differently in another.

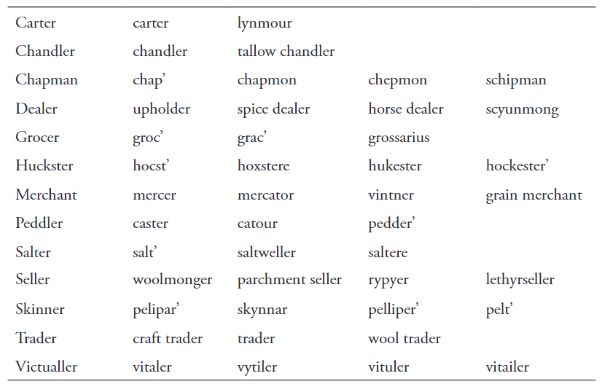

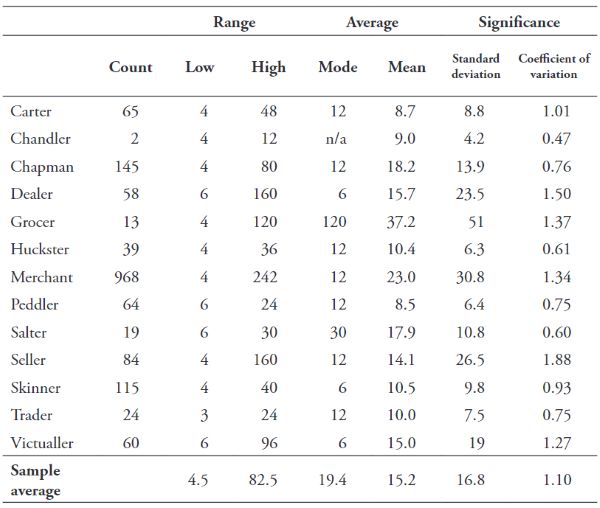

Before analysing the relationship between merchants and the military, the definition of a merchant must first be considered. Rather than limiting the definition to a strict set of individuals, merchants in the context of this chapter will be those engaged in mercantile activity, selling and buying either as generalists, such as grocers, or as specialists such as fishmongers. Of course, most occupations would have a trade element, whether for cash or in kind. However, in this chapter the focus will be on those whose occupations suggest involvement with secondary mercantile activity, rather than relying on their own produce for trade. The datasets gathered provide a myriad of different descriptions that fall within this definition, and Table 5.1 shows a sample of the various descriptions extracted from the letters of protection and poll taxes, grouped by standardized category.

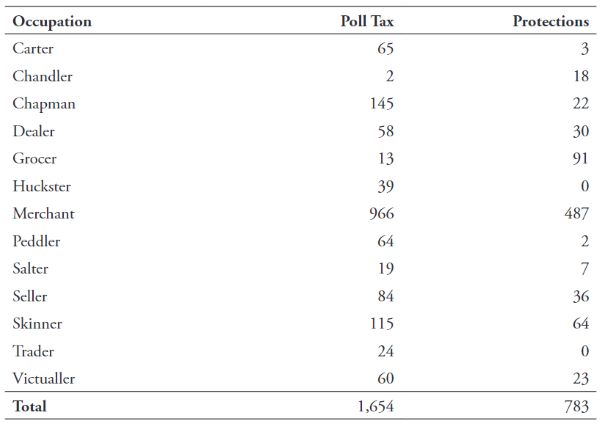

The samples drawn from the two datasets are then enumerated in Table 5.2, broken down by the standardized categories.

The letters of protection and appointments of attorney contained in the medieval soldier database have commonly been used in conjunction with muster rolls as part of the career reconstructions of individual soldiers, including military service where no musters have survived.30 Where a muster does not survive, we have to use our judgement, and sometimes the specific wording of the legal instrument, to decide whether the letters of protection or appointments of attorney are linked to intended military service. For instance, a well-known example of this is Geoffrey Chaucer, who despite not appearing in any extant muster roll appears to have taken out letters of protection in 137231 and 137732 for travel overseas to France, and in 1387, specifically for service in the Calais garrison.33 In the protections and attorney data there are 25,495 entries, of which 2,912 mention an occupation. If all descriptions that appear to have mercantile connections, including merchant, mercer, vintner, victualler, grocer, etc. are counted, a sample of 783 men is formed. From this there are only six who are described as both a soldier and some other kind of occupation. The earliest of these, Thomas Roo, is described as a soldier and victualler to the Sangette garrison in 1390.34 Interestingly, a few years earlier in 1387 there is a Thomas Roo described as a grocer in the Calais garrison;35 therefore potentially the same individual was engaged in supplying English soldiers in a mercantile capacity. There is possibly some career overlap between this man and Sir Thomas Roos, who appears many times in the protections between 1369 and 1381. However, it would appear that these were separate men, as Sir Thomas died in 1383. Furthermore, it would be unusual for documents to disregard established titles previously cited, such as Sir Thomas’s knighthood that is noted in protections as early as 136936 but not on the victualler/grocers’ protections from eighteen years later.

There are further examples of merchants acting in a military context. The London mercer John Gourneye was issued with a protection for service with Sir Thomas Swinburne at Roxburgh castle in 1386 for one year.37 Interestingly this overlaps exactly with a protection for service at Berwick castle under Sir Thomas Talbot.38 Clearly he cannot have been serving in both garrisons at the same time and the fact that both protections were issued on the same day makes it unlikely that two separate men were involved. Instead, although the protection does not explicitly state as much, it appears that John Gourneye was involved in the supply of both of the garrisons rather than service as a soldier.

The links between the Calais garrison and the merchant community may have been especially close, and the links between mercantile activity and a military garrison can be seen explicitly here. On 27 September 1391 Thomas Coteler, merchant of London, was issued a protection for one year and explicitly described as a ‘victualler of the castle’.39 This protection was renewed on 13 October 1392, with Thomas Coteler again described as ‘victualler of the castle’, and his place of origin noted as London.40 This second protection was allowed to lapse, and Thomas Coteler appears to have left Calais until 6 January 1394, when he again takes a protection as ‘victualler of the town’ of Calais for one year, on this occasion described as a citizen of London and grocer.41 This case highlights several points of note. Firstly, our definition of merchants must be sufficiently flexible to account for variations in language employed when drawing up these documents. Here Thomas Coteler is described separately as a ‘merchant’ and a ‘grocer’, indicating that merchant appears to cover a broad range of trades that can be considered mercantile. Secondly, this series of protections indicates that there was a consistent effort on the part of private individuals to supply Calais, i.e. merchants acting in a military context. Of the 3,191 protections connected to Calais, 162 have a mercantile connection, representing 139 different names. Of these, forty-eight men also appear in the muster rolls, suggesting that more than a quarter engaged in direct military service at least once. There are some interesting cases of merchants involved with Calais also appearing to serve as soldiers. For example, Adam de Bury of London, who is described as a ‘merchant’ in his protection for travel to Calais in 136942 and again in his 1373 protection,43 may be the same man who engaged in military service with Sir William Neville in 1374.44 If this is the case it is apparent that his mercantile activities took precedence over the military as he took out a total of five protections, with no corresponding military activity.45 These mercantile activities appear to have been somewhat suspect as Adam de Bury was impeached in the Good Parliament of 1376 for various malpractices connected with the trade of London and Calais, although he was later pardoned for these offences on 20 April 1377.46 In the case of John Michel, it appears that no military service was undertaken at all. He took six protections in the period between 16 January 1383 and 15 November 1390, and is described in the first as a mercer, and the remaining five as a vintner.47 However, although his captain is included in the details of each protection, this does not seem to have been a direct military connection, as the captain is Roger Walden, the treasurer of Calais, rather than a retinue leader. It should also be noted that in all of these examples the merchants are listed as originating in London, often being described as citizens of the city. The connection between London and Calais during this period appears to have been strong, mostly due to the heavy cross-Channel trade. This link is supported by the analysis of the protections, as ninety-seven (60 percent) of the 162 protections taken out are explicitly linked to London, with a further twenty-nine of unknown origin, and one from Calais itself. Only thirty-five (22 percent) can be shown to originate from other locations.

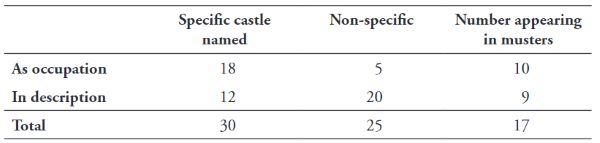

The case of Thomas Coteler provides a further example of a mercantile-military link. His description as ‘victualler of the castle/town’ makes the link between the merchant and military supply explicit, as victualler appears to be a used expressly in connection with the supply of castles. This is supported by its use throughout the protections, either as an occupational designation, or as a part of the description of the terms of the protection. An example of this latter category is Richard Loxlee, who took a one-year protection from 30 May 1402 for Guines castle, for the victualling of the castle, despite his occupation being given as a grocer.48 In total there are fifty-five protections that refer to a victualler (Table 5.3).

It would appear then that the term ‘victualler’ was used in a distinct manner by the clerks drawing up these documents: one that connected the mercantile to the military. A majority of the extant ‘victualler’ protections are from the fifteenth century, a logical pattern probably influenced by the increased permanency of the English military presence in France following the invasion of Normandy in 1417. There is a slight predominance of those who were described as victuallers, but noted as having a different occupation; however, despite this, the occupational victuallers have a proportionally higher rate of military service, suggesting that those described as victuallers had a closer connection to the military. The term only appears on a minority of the surviving protections; however, its use does support the idea of private mercantile enterprise supporting the military, which in itself was partially based around private enterprise.

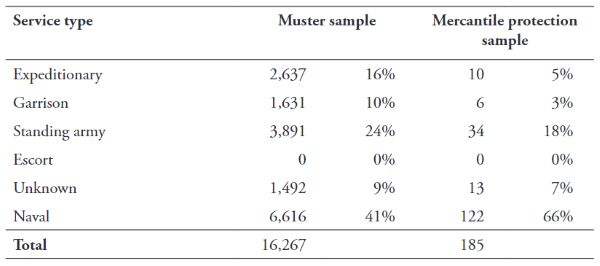

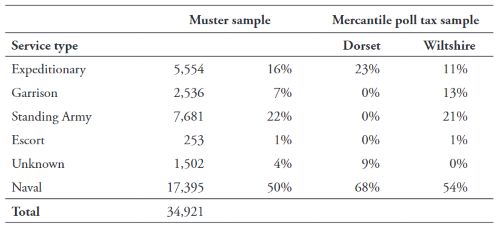

The relationship between merchants and the military also continued into military service, with merchants appearing as soldiers throughout the later fourteenth century. However, when the men described as merchants in letters of protection or appointments of attorney served as soldiers, it appears that they demonstrated some differences to their non-merchant colleagues. Extracting a sample of the mercantile protections granted in the 1380s produces a sample of 185 men who can be compared to the service records in the muster rolls (Table 5.4).By limiting the muster sample to the same decade as the protection samples, the strength of the nominal linkage is greater than if a larger sample of muster records were used. The muster sample contains 16,267 entries, of which 6,616 or 41 percent are considered to be naval, i.e. those campaigns where soldiers were operating from ships rather than just being transported. However, when the mercantile protection sample is compared to the muster rolls, the percentage engaged in naval expeditions is noticeably higher at 66 percent.

This preference for naval activity has come primarily at the expense of expeditionary service, which has a difference of 11 percent between the two samples. Garrison service and service in standing armies also show a noticeable drop in service rates from the muster sample in comparison to the mercantile protections. It is possible that this predominance of naval service across the 1380s has skewed the proportional rates evident in both samples, and it must be noted that only four of the twenty-five musters from this period were in connection with naval service. However, despite this imbalance the large difference of 25 percent between the muster and protection samples in Table 5.4 is noticeable. It is possible that this increase was the result of close links between the mercantile community and the need to protect water borne trade, or perhaps it was due to the mercantile individuals living in or near ports or other coastal areas, and therefore a higher proportion of men were more comfortable at sea, operating ships.

The poll tax returns discussed above can also provide some insight into mercantile/military overlap. Of the 264,350 people in the poll tax records, only men who can be identified as mercantile will be required for this chapter, reflecting the fact that women were not formally engaged with the military. This provides a sample of 1,566 entries, which can be further subdivided into Section 1, 1,386 names which appear in the poll taxes only once, and Section 2, which comprises sixty-nine names appearing in multiple instances and represents the remaining 173 records. These entries from Section 2 are less useful for considering individual trends as they represent multiple occurrences of the same name, each one representing a distinct individual, a result of the nature of the poll tax being executed on a per capita basis, and not taxing any one person in more than one location. This means that any nominal record linkage will be uncertain and weak. This differs from the muster data, where multiple entries of the same name can be the same person engaging in repeat military service.

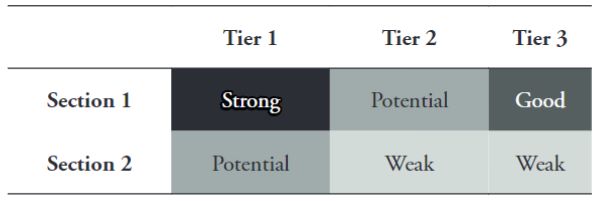

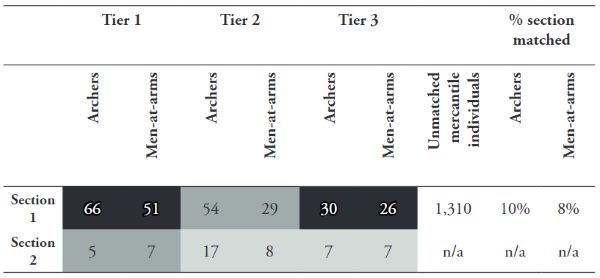

It is also worth considering the soldier sample that will be employed in this analysis. This chapter will concentrate on the 33,895 nominal muster records for archers and men-at-arms that date to within ten years of the poll taxes. This increases the potential for any nominal linkage to be accurate, as the limited chronology restricts the possibility of a false positive.This sample has been further refined into three tiers, each with different characteristics, to improve the quality of the analysis.Tier 1 comprises the 19,606soldiers who only appear on one occasion in the musters, and includes 10,450 archers and 9,156 men-at-arms. These names are the easiest to link as they are unique and a match to a poll tax entry has little chance of being incorrect. Tier 2 contains 9,674individual service entries, covering a total of 3,276 unique names, including1,873 archers and1,403 men-at-arms. These are the muster records where a name has appeared on more than one occasion, but in the same year, making it likely that there was more than one individual with that name and therefore making any nominal links between the muster entry and the poll tax weak.The final group, Tier 3, is drawn from the soldiers that appear to have engaged in service on multiple occasions, and have more than one muster entry in their name, but in different years, and total 4,600 entries, including 1,015 named archers serving on 2,332 occasions and 1,017 men-at-arms serving on 2,268 occasions. They represent a more professional group of soldiers, and will be considered separately to see if there is any particular overlap between the emerging military professionals and merchants. Separating the different types of data extracted from the dataset in this manner enables the different nominal links to be grouped by the probability of a link being accurate. A representation of the strength of the nominal linkages between the poll tax sections and the muster tiers is shown in Table 5.5.

These probability groups highlight not only where the nominal linkage is strongest, but also where the matches between the two datasets is most likely to be significant. For example, it is highly unlikely that the nominal matches between the multiple occurrences of both poll tax and muster names could be considered significant, as it is difficult, if not impossible, to conclude that any pair generated are the same individual. However, the stronger links generated with Section 1 provide more scope for analysis.

The muster sample contains 18,485 service records for archers and 15,344 for men-at-arms, a difference of just under a fifth. This indicates that the percentage of matches made between the two military ranks will be a fifth bigger for the archers, which is reflected in the percentage of Section 1 names that are matched to each rank in Table 5.6. This suggests that merchants as a group reflected the socio-economic mixture of the men who formed the English armies, and that they came from across a range of social strata. However, it does appear that knights were highly unlikely to be described as mercantile, as there are only six occasions where a Section 1 name matches to the name of a knight in the muster rolls, in comparison to 171 matches to the rank of esquire.

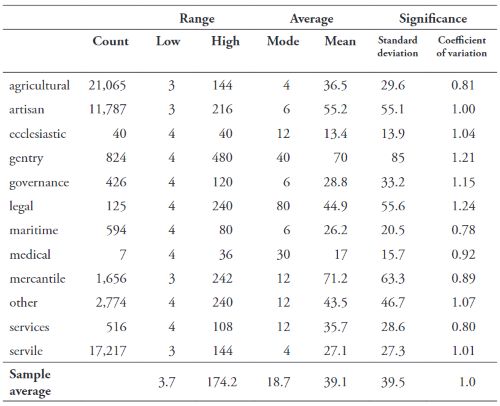

Alongside direct evidence of their military service, the poll tax records also provide an opportunity to delve further into the lives of mercantile individuals. As the returns can provide nominal, occupational and economic data for an individual they can provide a picture of the economic status of mercantile individuals. By looking at the levels of tax paid by these merchants in the 1379 and 1381 collections, a snap shot of their economic power can be extracted. These two years were graduated by ability to pay, unlike the flat per capita tax of 1377 and therefore differences in wealth are apparent. Table 5.7 shows how the different occupations within the mercantile group compare with each other, and how the ‘merchant’ occupation dominates the group, containing the wealthiest individuals having one of the highest average payments, despite having the largest sample size and highest proportions of persons paying the minimum rate of 4d.

Taken as a whole, the mercantile group compares favourably to other occupational groups and possesses one of the highest levels of economic status of the groups in Table 5.8, with the highest mean and the third highest mode. This indicates that despite not having the richest individuals, which are found in the gentry group, it has strength in depth, and has a large group of wealthy individuals. This reflects the breakdown of service shown in Table 5.6, with a high proportion of mercantile military service being performed as men-at-arms.

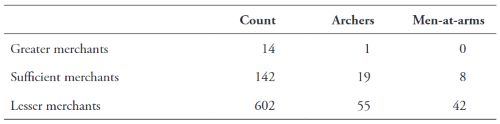

This link between economic standing and military status can be developed by breaking down the merchant category further. The 1379 poll tax schedule of charges specified different rates depending on the status of the merchant, dividing them into greater, paying 160d or more, sufficient, paying between 160d and 40d, and lesser, paying 40d or under. Using these economic criteria, the poll tax merchants, those who are explicitly described as merchants rather than those from mercantile occupations, who come from Section 1 (the uniquely named individuals) will be compared to the muster sample used above, covering the period 1367 to 1391.

The results shown in Table 5.9 are somewhat limited by the variation in sample size. However, it does provide confirmation of the results shown in Table 5.6, with the average match between archers and the merchants of 9 percent and men-at-arms and merchants of 5 percent.

The poll taxes also enable an analysis of mercantile service by service type, in the same manner as the protections (Table 5.4). By using the two data resources in a similar fashion, where possible, it will improve the certainty of any conclusions drawn and reinforce the evidence of one of the sources. the merchants originating in the coastal county of Dorset, compared to the inland county of Wiltshire. This proportional increase does not appear in the non-mercantile populations of these counties, where the rates of naval service for both counties slumps to 30 percent of matching records. This supports the idea that it was more likely for a mercantile individual to engage in naval service than his non-mercantile compatriot; however, this trend is more tangible in coastal areas, where a stronger maritime tradition could be apparent. The sample of musters used here covers the period 1367–91, within ten years of the poll tax, and this sample breaks down with the same proportions of naval, expeditionary, garrison, standing army, and escort service as the muster sample used for comparison against the protections. The poll tax records do not immediately demonstrate a difference between mercantile and non-mercantile naval service, unlike the analysis of protections in Table 5.4. However, by investigating a little deeper into the poll tax/muster overlap it is possible to see some distinguishing mercantile features.

For example, looking at different counties reveals a more detailed picture. It is apparent from Table 5.10 that there is a higher proportion of naval service among the merchants originating in the coastal county of Dorset, compared to the inland county of Wiltshire. This proportional increase does not appear in the non-mercantile populations of these counties, where the rates of naval service for both counties slumps to 30 percent of matching records. This supports the idea that it was more likely for a mercantile individual to engage in naval service than his non-mercantile compatriot; however, this trend is more tangible in coastal areas, where a stronger maritime tradition could be apparent.

The importance of mercantile activity in the fourteenth century to the English crown and its revenues generated a huge amount of documentation leading to a large body of historiography, disproportionate to the economic structure of England at the time. Despite this over-representation, the links between merchants and the military have not previously been discussed in depth, an omission that appears odd, given that warfare represented one of the English king’s greatest expenditures, and an omission that this chapter has tried to correct. It has been shown that there was a great deal of overlap between the mercantile and military spheres. Merchants were not exempt from service in the English armies, and engaged in service in many different theatres, with a notable emphasis on the naval campaigns. The evidence of the poll tax returns and the protections also suggests that mercantile individuals were of higher economic status than the average person, a hypothesis supported by the proportionally higher rate of service as men-at-arms. Importantly there is also evidence of merchants who were involved in the military, but not necessarily as soldiers. Instead, there is evidence suggesting that the crown was aware of the need to supply its armies and garrisons, and that it was willing to allow a certain amount of private enterprise to ensure that this logistical task was carried out. This area of mercantile activity appears to have acquired a distinct title, that of ‘victualler’. In summary, there are links between the mercantile and the military, and the logistical needs of the English armies appear to have been met, in part, by private enterprise reminiscent of the indenture system used to recruit soldiers.

Endnotes

- W. P. Caferro, ‘Warfare and economy in Renaissance Italy’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xxxix (2008), 167–209.

- Information on soldiers has been taken from A. Bell, A. Curry, D. Simpkin, A. King and A. Chapman, The Soldier in Later Medieval England Database <http://www.medievalsoldier.org> [accessed 30 Sept. 2009].

- S. Gibbs, ‘Database of poll tax returns’, unpublished.

- A. Bell, C. Brooks and P. Dryburgh, The English Wool Market, c.1230–1327 (Cambridge, 2007).

- P. J. P. Goldberg, ‘Urban identity and the poll taxes of 1377, 1379, and 1381’, Economic History Review, xliii (1990), 194–216, at p. 214.

- M. M. Postan, ‘The costs of the Hundred Years War’, Past & Present, xxvii (1964), 34–53; M. Kowaleski, ‘Warfare, shipping and crown patronage: the economic impact of the Hundred Years War on the English port towns’, in Money, Markets and Trade in Late Medieval Europe, ed. L. Armstrong, I. Elbl and M. M. Elbl (Leiden, 2007), pp. 233–56.

- A. Bell, A Curry, A. King and D. Simpkin, The Soldier in Later Medieval England (Oxford, 2013).

- A. Ayton and C. Lambert, ‘A maritime community in war and peace: Kentish ports, ships and mariners, 1320–1400’, Archaeologia Cantiana, cxxxiv (2014), 67–104.

- S. L. Thrupp, The Merchant Class of Medieval London 1300–1500 (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1989), p. 49.

- C. C. Fenwick, ‘The English poll taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381: a critical examination of the returns’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 1983).

- ‘The form of each poll tax was quite different. In 1379, married women were excluded … the effects of this were, at the time, and have been since, seriously underestimated. No two poll taxes were levied from the same age range. Thus, those who paid as fourteen year olds in 1377 paid again as sixteen year olds in 1379, but those who were twelve in 1377 did not pay in 1379 when the exemption level was raised by two years … It is not surprising that the number of taxpayers recorded was quite different for each tax. Thus, some of the discrepancies we seem to find are the result of a careless reading of the rules laid down for the taxes’ (Fenwick, ‘The English poll taxes’, p. 167).

- Goldberg, ‘Urban identity and the poll taxes’, pp. 194–216.

- S. Sweetinburgh, ‘The social structure of New Romney as revealed in the 1381 poll tax returns’, Archaeologia Cantiana, cxxxi (2011), 1–22.

- K. Bailey, ‘Buckinghamshire poll tax records 1377–79’, Records of Buckinghamshire, xlix (2009), 173–87.

- G. Baker, ‘Investigating the socio-economic origins of English archers in the second half of the fourteenth century’, Journal of Medieval Military History, xii (2014), 173–216.

- A. E. Prince, ‘The indenture system under Edward III’, in Historical Essays in Honour of James Tait, ed. J. G. Edwards, V. H. Galbraith and E. F. Jacob (Manchester, 1933), pp. 283–97. For a recent and up-to-date summary, see Bell and others, The Soldier in Later Medieval England, pp. 7–10.

- A. Bell, War and the Soldier in the Fourteenth Century (Woodbridge, 2004), p. 34.

- Bell and others, The Soldier in Later Medieval England, pp. 4–7.

- Fenwick, ‘The English poll taxes’, p. 24.

- A. Ayton, ‘Edward III and the English aristocracy at the beginning of the Hundred Years War’, in Harlaxton Medieval Studies, ed. M. Strickland (Stamford, Calif., 1998), pp. 173–206.

- D. Simpkin, ‘Robert de Fishlake: soldier profile’, The Soldier in Later Medieval England Database <http://www.medievalsoldier.org/February2008.php> [accessed 9 Sept. 2010]; TNA: PRO, E 101/39/9, m. 5d, listed as Robert Fysshlake.

- See several of the tables in Bell and others, The Soldier in Late Medieval England: table 24 on p. 190 is an especially good example of how the spelling and status of individuals could change between campaigns.

- Bell and others, The Soldier in Later Medieval England, cite several examples, including one Peter Toron, who served as an archer in 1372 and a man-at-arms in 1377, whose surname is very unusual (p. 145).

- Bell and others, The Soldier in Later Medieval England, p. 148.

- P. Morgan, War and Society in Medieval Cheshire (Manchester, 1987), p. 109.

- A. Ayton, ‘Military service and the dynamics of recruitment in fourteenth-century England’, in The Soldier Experience in the Fourteenth Century, ed. A. Bell, A. Curry, A. Chapman, A. King and D. Simpkin (Woodbridge, 2011), pp. 9–60.

- TNA: PRO, E 101/40/33, m. 7d; E 101/34, m. 11.

- A. Chapman, ‘The Welsh soldier, 1283–1422’ (unpublished University of Southampton PhD thesis, 2009), p. 262.

- Chapman, ‘The Welsh soldier’, p. 263.

- See the chapter on ‘The men-at-arms’, in Bell and others, The Soldier in Later Medieval England, pp. 95–130.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/55, m. 9.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/60, mm. 5, 7.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/72, m. 27.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/74, m 3.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/71, m. 51.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/52, m. 15.

- TNA: PRO, C 71/66, m. 8.

- TNA: PRO, C 71/66, m. 8.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/76, m. 15.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/77, m. 10.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/78, m. 12.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/52, m. 21.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/56, m. 23. This protection explicitly describes him as a citizen of London, rather than just noting his place of origin.

- TNA: PRO, E 101/33/16, m. 1.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/53, m. 26; C 76/54, m. 16, and C 76/55, m. 42.

- Rotuli parliamentorum ut et petitiones et placita in parliamento, ed. J. Strachey and others (6 vols., 1767–77), ii. 330; CPR 1374–1377, p. 453.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/76, m. 18; C 76/72, m.25; C 76/73, m. 17, and C 76/74, m. 24; also CPR 1389–1392, p. 26.

- TNA: PRO, C 76/86, m. 4.

Chapter 5 (93-112) from Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, edited by Martin Allen and Matthew Davies (Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 06.30.2016), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons