Examining anti-immigrant rhetoric, legislation, violence, and hostility at the time.

By Dr. Matthew Davies

Executive Dean, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

Professor of Urban History

Birkbeck, University of London

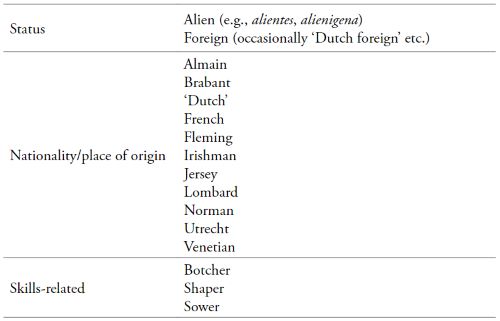

London has always been a city of migrants, its demographic and economic growth fuelled by immigration from the English regions and other parts of the British Isles and by periodic influxes of migrants from continental Europe and further afield. Migration therefore represents a long and continuous thread in the history of the capital that allows reflections not only on the history of particular communities (Italians, Huguenots, Greeks, Germans, Jews), but on the nature of the city itself as a place of life and work and as an entrepôt for peoples, ideas and commodities. This was certainly the case in the later middle ages, when it has been estimated that there were approximately 3,500 aliens in London at any one time, representing some six percent of the post-Black Death population.1 ‘Alien’ (alienigena in Latin) was the term that denoted someone born outside the realm; and in the case of London this differentiated them from ‘foreign’ (forinsecus), a term normally used (in this context) to describe a migrant from elsewhere in the realm who was not a citizen of London.2 These and other terms were deployed by contemporaries in a variety of contexts – cultural as well as political and legislative – as part of efforts to identify, differentiate, characterize and restrict the activities and roles of aliens and, indeed, ‘strangers’ more generally.3 What roles did aliens play in the economy and society of late medieval London? This essay seeks to contribute to discussion about the participation of aliens in the trades of the medieval city by focussing particularly on their links with guilds and by extension the nature and limits of those organizations’ jurisdictions and roles. The argument here is that the roles of aliens, like other non-citizens, have generally been underplayed by historians and that a better understanding of those roles provides a richer sense of the nature of productive networks and the relationships between aliens, guilds and citizens – relationships often vividly expressed at moments of crisis.

Research on aliens in London in the period after the expulsion of the Jews in 1290 and before the establishment of the first Protestant stranger church in 1550 generally has focussed on two main areas. First, historians and projects have sought to produce accurate surveys of the numbers and types of aliens in the capital. Sylvia Thrupp pioneered research in this area, using the alien subsidy records and other sources to provide estimates of the numbers of aliens in the capital. Her figures have been modified since, first by Jim Bolton’s work on the alien subsidy rolls for London from 1440 and 1483; and most recently through the detailed work on the subsidy rolls for England as a whole and on royal letters of protection and denization by the Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded England’s Immigrants project.4 Much of this work has been quantitative in nature, assessing the numbers of aliens by origin and by occupation, where such information exists, providing a valuable context for more qualitative research undertaken in the last few years, notably by the England’s Immigrants team of researchers, which is transforming our understanding of the alien presence.5

Alongside the largely quantitative, ‘top-level’ work, research of a more qualitative nature has tended to focus on the most prominent and wealthiest migrants, notably the Italians and the merchants of the Hanse. Although relatively small in numbers compared with aliens from the Low Countries and German lands, the Italians were of undeniable importance because of their involvement in trade, banking and diplomacy; and studies by Michael Bratchel, Helen Bradley, Suzanne Dempsey and others have uncovered much about particular families (such as the Datini) and their networks.6 Bradley’s digital and hard-copy editions of the ‘views of hosts’ reveal in extraordinary detail the interactions between alien and non-alien merchants and the level and type of transactions in which they were involved. Interestingly, they reveal, in a politically hostile climate, the close relationships between London and alien merchants. Much more information about finance and trade has been revealed by studies of London merchants such as William Cantelowe and especially by the work of Bolton and his colleagues on the banking ledgers of the Borromei family in London and Bruges.7 The role of the Hanseatic merchants in England, and particularly their presence in London at the Steelyard, have been another active area of research among scholars in the UK and on the Continent for more than a century, with more recent contributions from T. H. Lloyd, Stuart Jenks and others.8

When it comes to alien craftsmen and their English counterparts in London, attention has often focussed on moments of crisis rather than on in-depth analysis. In 1468, for example, the city of London authorities uncovered a plot hatched by a large group of artisans – mostly goldsmiths, skinners, tailors and cordwainers – to cross the River Thames to Rotherhithe on the south bank and, because ‘the Flemings there take away the living of English people, [they] purposed to have cut off their thumbs or hands so that they should never after that have helped themselves by means of craft’.9 This relatively well-known incident has often been cited in debates about the roles of, and reactions to, non-English migrants in the capital city in the later middle ages and especially the relationships between London craftsmen and their migrant counterparts. Others include the violence and hostility directed to Flemings during the 1381 revolt, the anti-Italian rioting of 1456 and, most famously, the ‘Evil May Day’ disorder of 1517 involving London apprentices. Much of this historiography has drawn on the vivid accounts in chronicles and other sources, which perhaps tend to skew our perceptions because of their focus on ‘extreme’ events.10 Similarly, attention has focussed on formal and legislative responses by governments and organizations, such as the alien subsidies of the late medieval period; different kinds of restrictions placed on alien economic activity by governments and guilds; and the petitions from the London crafts against the employment of alien and, indeed, other migrant labour that were sent to the city government and even to parliament in the later middle ages. Much of this lobbying took place at a time when guilds and civic authorities were especially conscious of the effects of economic recession on the opportunities available to their own members – at least in terms of these ‘high level’ interventions.11

The purpose here is to try to put the anti-alien rhetoric, legislation, violence and hostility into a wider context and to bring additional perspectives to bear on what are often polarized debates about control and conflict on the one hand and ‘integration’ and ‘assimilation’ on the other. Thrupp’s assertion of a degree of mutual respect between aliens and other Londoners is not necessarily incompatible with scepticism from Bolton and others about her evidence for ‘assimilation’ in London.12 Here, an important starting point is our relatively poor understanding of the world beyond the formal structures of the city, guilds and parish, the focus of most of the historiography. This is understandable, perhaps, given the nature of the sources, but nonetheless there is considerable potential to use existing sources to study the ways in which non-citizens – whether English or non-English residents – participated in the London economy and interacted with each other as well as with formal institutions such as the guilds.13 Recent work has begun to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of aliens in London society by using sources which tell us more about the lives and connections of the aliens themselves. These complement and enhance what we can learn from subsidy records, for example, or from moments of crisis such as 1381, 1456 or 1517, which, though important, are not the only lenses through which interactions should be explored.14 The work of Bolton and others on the Borromei banks and of Bradley on the ‘views of hosts’ has been extremely important in shedding light on the relationships between London merchants and alien merchants and how they interacted in networks of international trade and finance.15 Elsewhere, there has been a great deal of interest in the culture and practices of migrant communities in cities in Europe, much of it taking the form of further discussions about the ways in which migrants interacted with host communities by looking at the nature and effectiveness of institutional structures as well as cultural attitudes.16 For London, Erik Spindler, for example, has explored the concept of ‘portable communities’ in London and Bruges, examining mental frameworks and communal structures that existed within transient populations.17 Justin Colson’s work on alien fraternities in medieval London has looked at the ways in which migrants established fraternities to foster and preserve identities, while at the same time (because they had to be located somewhere) interacting with London institutions such as the religious houses.18 While most of these studies have concentrated on the upper strata of the alien community, they do at least provide some useful pointers and concepts to deploy when studying craftsmen and women further down the social and economic scale.

The history of the alien presence in London connects in significant ways with broader narratives and frameworks in urban and metropolitan history, but these have perhaps not been considered as much as they might have been. One of the characteristics of much of the work on medieval London is that it is overwhelmingly focused on citizens and their careers, trading activities, institutions, parishes and so on. In part, this of course reflects the nature of the sources – we do not have the richness of sources such as the Bridewell court records of the mid sixteenth century, for example, which are of immense value for studying social life, culture and economic activity beyond the formal structures of London society.19 For the later middle ages most of our sources are those created by formal city institutions, which promoted citizenship through a rhetoric of inclusion and exclusion and idealized career paths and modes of production. This was particularly the case with the city companies or guilds, which created and promoted what one historian has termed a ‘myth of the metropolitan experience’, centred on apprenticeship and citizenship as the route to financial and social success.20 Yet we need to remind ourselves that citizens were a distinct minority of Londoners – in fact, of a population of around 50,000 after the Black Death, it has been estimated that only about 4,000 were citizens – a quarter of the adult male population. Citizenship was intricately connected with the craft and merchant guilds: from the early fourteenth century onwards they were responsible for controlling apprenticeship, which was the most popular route to the freedom of the city.21 As a result, economic activity in London has very often been studied and represented principally in relation to citizenship. Exceptions notably include work on women, such as Anne Sutton’s work on silkwomen (though many of these were closely connected with members of the Mercers’ guild), or Judith Bennett’s study of the role of women in the brewing industry, both of which take us beyond formal structures and into the wider world of work and retailing.22 But in the main we still lack studies of work and production which look at the roles of non-citizens, and especially aliens, in productive networks and their interactions with these formal structures. We can usefully, for example, draw inspiration from the approaches and conclusions of early modern historians such as Lien Luu, who has studied aliens in early modern London through this kind of wider perspective on urban crafts, which in her case have allowed her to assess the role of alien skills and know-how in transforming the city’s economy.23

Luu has made good use of guild records in her work and a second strand or framework that is useful here is research on the roles and functions of guilds themselves in urban society. This has been a lively area of debate over recent years, which has focused attention on the extent to which guilds either hindered or promoted innovation and entrepreneurship in the urban economy.24 Looking beyond ‘normative’ legislative frameworks, some historians have emphasized the flexibility of guilds in practice, seen in their employment practices, selective and pragmatic enforcement of regulations and so on.25 This is one way in which we might try to bring aliens and their work and skills more fully into the picture of industrial and economic development in late medieval London. Elspeth Veale, in one of her many important contributions to studies of the city’s craftsmen, raised some key questions about economic and productive networks in the city and especially the significance of ‘non-citizen’ labour within the frameworks established by the guilds themselves.26 Her work prompted this author’s own examination of how the London guilds considered English non-citizens, ‘foreigns’, which seems to suggest – perhaps unsurprisingly – that the complexities of the urban economy simply cannot be straightforwardly represented in terms of narratives of inclusion and exclusion. Indeed, reliance on non-guild labour and skills was a hallmark of London’s economy, as it was for cities across Europe in the middle ages.27 What roles did alien craftsmen occupy in relation to the city’s guilds, beyond what is implied by anti-alien sentiment or indeed ‘directed’ by official pronouncements and legislation, even in times of crisis?

Research on the role of aliens needs to be integrated into some of these broader ways of studying cities in general and London in particular and especially its economic structures and modes of production beyond those which were defined narrowly by the city government and by the guilds. This could be a useful strand of future research on aliens in London and its suburbs: assessing the extent to which alien labour and skills underpinned certain trades and the ways in which guild policies and practices interacted with these wider economic ebbs and flows. For example, the second half of the fifteenth century saw a noticeable increase in anti-alien petitioning and legislation at guild, city and national level. What was behind this? How representative were these concerns of the needs of craftsmen on the ground and the availability of labour and skills? To make sense of this, or rather to contextualize it better, we need to understand structures of production and the dependencies they created, but also reactions to wider circumstances such as economic and demographic change and how they impacted on economic relationships.

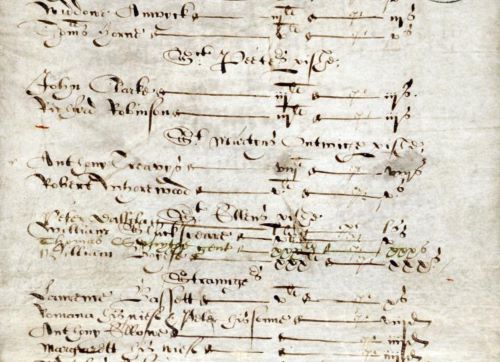

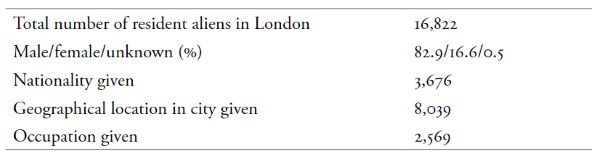

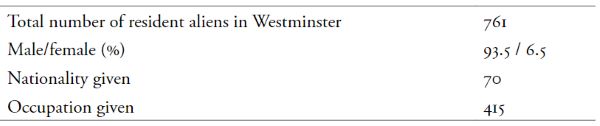

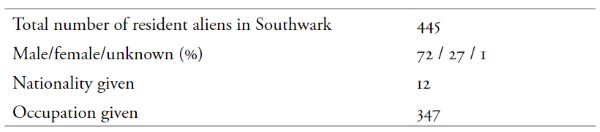

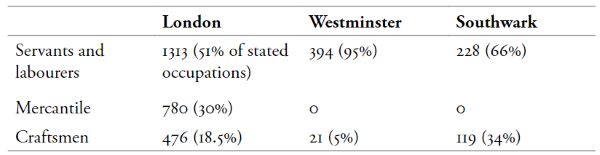

Before discussing some of the evidence that might help to answer these questions, we need to start with a sense of the overall picture, as provided by the England’s Immigrants project through its analysis of the alien subsidy records in particular.28 This is very much an overview – much more detailed analysis of the London records has been written up by the project team online and in print.29 The data from the alien subsidy records contain some 16,822 instances of resident aliens in the city of London in the later middle ages, with 836 in Westminster and 657 in Southwark (Tables 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3). The vast majority of the London resident aliens were listed in the tax assessments between 1441 and 1488, although the nature of the sources means that they were likely to exclude more ‘transient’ aliens as the subsidies were based on households and residence.30 Other sources, such as oaths and letters of denization, include a further 500 or so instances of aliens from across the late medieval period, but these have been excluded from the statistical analysis here as they are heavily weighted towards merchants rather than providing a cross-section of the alien population. Tables 6.1 to 6.3 indicate where information about gender or occupation is given; and also where ‘nationality’ is indicated, although it is important to note that in this context national labels could be both specific (‘Lombard’) but also rather broad: ‘Theutonicus’ and ‘doche’, referring to migrants from the Low Countries and German lands, for instance.

As well as names, the data include characteristics of different kinds – nationality, location, occupation and so on – although these characteristics are particularly common in certain sources such as the subsidy of 1483 and are not uniformly present.31 There is much to be gained by combining and analysing these characteristics and taking a broad view across the period, as well as by drawing out key changes over time. It is important to note at this point that we are working here with mentions or instances of aliens: some individuals crop up more than once in the various sources, for example across the alien subsidy records of the fifteenth century, and one would expect merchants to be more prominent and frequent in these sources. As a result, we are not dealing with 16,800 ‘individuals’ in the city but 16,800 instances in the sources. However, with that caveat, it is nonetheless useful to aggregate the data to see what patterns emerge from them as a way of identifying characteristics and lines of further enquiry. This, in many ways, builds on the analysis of the alien subsidy rolls carried out by Bolton and published in 1998 and on Lutkin’s analysis from 2016.32

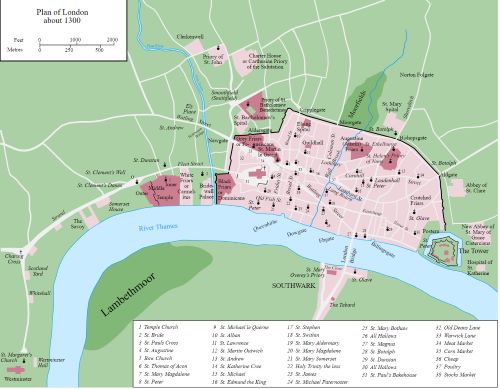

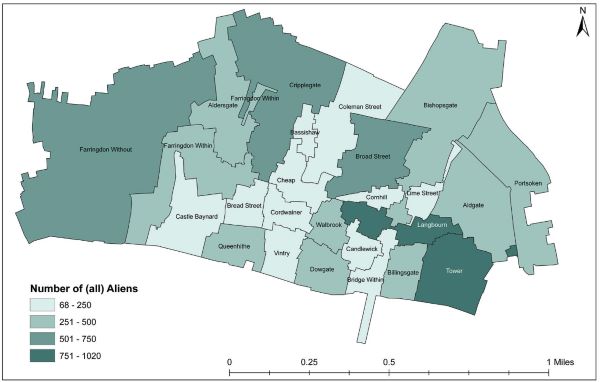

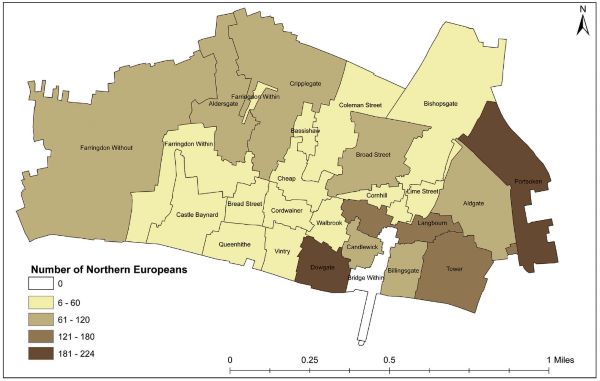

To start with, if we look at places of residence overall within the city of London, the pattern of distribution of mentions of aliens of all nationalities across London’s wards can be visualized using a map (Figure 6.1). These, of course, are raw figures; ideally they would be ‘normalized’ using ward populations, but those are not easy to determine for this period. The maps also aggregate the figures from the 1441 and 1483 subsidy returns: these were not identical in terms of their scope; and cross-referencing between the two sets of records shows the way in which some aliens moved around the capital. Nonetheless, as Bolton and the England’s Immigrants project have found, such a high-level visualization of the alien presence in fifteenth-century London reveals some important patterns. We can see, for example, that the central ward of Langbourn was most associated with aliens, followed by Tower, Farringdon Without and Broad Street, with uneven distribution across the city.

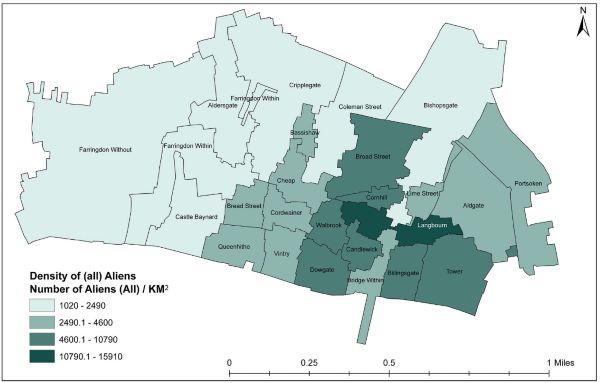

It is possible to refine this picture slightly by taking into account the geographical sizes of wards (Figure 6.2). This appears to show even more of a concentration in the central and eastern wards. However, a significant caveat here is that some of the extramural parishes were not as fully built up as they were to become in the sixteenth century, so this overstates the contrast to a degree.

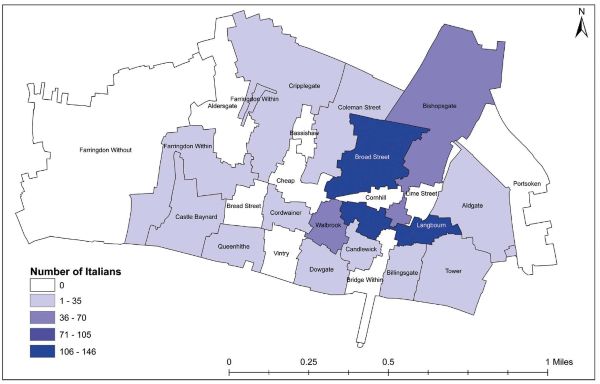

This broad pattern does, of course, raise questions about who these aliens in Langbourn and the other wards were. If we include ‘nationality’ as a characteristic, we can see that there are some clear differences. Figure 6.3 shows the distribution of Italians across the wards: Langbourn is again the most heavily populated ward, but there was a clear concentration in the centre of the city.

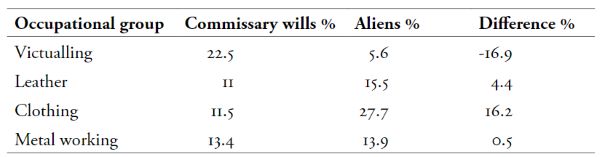

This ward contained Lombard Street and was well-known as a centre of activity for Italian merchants and bankers in the later middle ages.33 If we turn to the northern Europeans, we can see a very different picture (Figure 6.4). In this case, there is a much greater presence in the peripheral areas of the city. We already know from studies by Bolton and Lutkin, and from analysis of the England’s Immigrants data, that (to put it very simply) most of the Italians were merchants and most of the northern Europeans (mainly Teutonic/German) were craftsmen of different kinds. What we have is a classic picture of urban migration common to many other towns and cities in Europe: merchants congregating in the centres of power and finance, able to access individuals, markets and institutions, while migrant craftsmen were, in many cases at least, drawn to cheaper, marginal areas, where they attempted to set up shops and businesses. Portsoken and Aldgate to the east of the city, for example, were already taking on the socially and nationally diverse character which they were to retain throughout the early modern period. Once again, this analysis does not reflect variations over time and within the assessments: the exemption of the Italians from the 1483 subsidy, for example, was probably responsible for a sharp drop in the numbers of aliens in Langbourn ward in that year.34

The occupational structure of London’s alien population is an important means of understanding their contribution to, and participation in, the city’s economy – and especially how their activities mapped onto the trades practised by Londoners. Where occupations are mentioned (mostly in the 1483 subsidy rolls), we can see that there were large numbers of merchants in the city itself (or those with related mercantile occupations such as broker, factor, merchant’s clerk), a fact which helps to explain the overall residential pattern there. Outside the city there were few merchants, at least in terms of occupations reported in the subsidy returns (see Table 6.4). Servants formed a large group in the three areas, being especially numerous in Westminster, and constituted around half of reported occupations in the city and in Southwark. The term ‘servant’ almost certainly covered a range of positions and relationships to householders, including apprentices (such as those of the goldsmiths discussed below), journeymen and live-in servants. A great many of these were the servants of fellow aliens, while others, particularly in London, may have been servants to citizens – and, as we shall see, this links very well with the evidence from the guilds. It is also important to emphasize the frequent instances of alien wives recorded in the subsidy returns as living with their householder husbands, especially migrants from the Low Countries: like their native counterparts, many would have been involved in the household business or undertaken complementary activities such as brewing. As Table 6.4 shows, there were 476 instances of aliens in London with a specific occupational designation as craftsmen, not including the servants or the mercantile trades.

In contextualizing the alien craftsmen of London, it is possible to use, as a rough comparator, Caroline Barron’s analysis of the city’s occupational structure as represented in the thousands of testators whose wills were proved in the commissary court of London (Table 6.5).35 By comparing this picture with the distribution of aliens in the same categories it is clear that aliens were relatively more likely to be involved in the leather and clothing trades. Within these broad descriptors there are some significant patterns: a remarkable three-quarters of the alien metalworkers were goldsmiths, rather than the more typical mix of ironmongers, pewterers, cutlers and other crafts that we see among the host population. Historians such as Jenny Stratford and Jessica Lutkin have emphasized the valuable skills brought by alien goldsmiths; and their prominence in London raises some interesting questions (to be discussed later) about their relationships with native English goldsmiths and the London guild.36 Eighty-three percent of the leatherworkers were described as cobblers, cordwainers or shoemakers, emphasizing their manufacturing activities rather than involvement in the preparation of leather. While the overall proportion of victuallers is lower among aliens, more than fifty percent of them in the city were beer-brewers: aliens had brought beer (rather than ale) brewing to London in the early fifteenth century and dominated it into the early sixteenth.37 Finally, more than three-quarters of those aliens stated as being involved in the clothing industry were designated as tailors or cappers.

We can see similar patterns to these in Southwark in particular, where several crafts were especially prevalent within the same broader categories: fifteen cordwainers (thirteen percent of stated non-service occupations), fourteen tailors (twelve percent), and eleven goldsmiths (nine percent). Considered together, these figures provide us with a useful overview of the main sectors of the economy that we might look at more closely to understand some of the structural issues that might have underpinned attitudes and responses to aliens. These sectors reflect significant changes in consumer demand in the hundred years after the Black Death of 1348/9, which can also be seen in customs accounts – new clothing styles and dress accessories were especially significant, as were the skills brought by alien goldsmiths.38

The second part of this essay will take a qualitative approach to the relationships between guilds and citizens on the one hand and alien workers on the other. This means trying to delve beneath anti-alien complaints and legislation and to look more closely at the evidence for production and participation within the trades in which aliens were numerically prominent. This is not to say that those complaints were not significant; and indeed the work of Caroline Barron, Jim Bolton and others has charted the ebbs and flows of anti-alien hostility and legislation – including, of course, measures such as the alien subsidies themselves. These were far from being the whole story of interactions between aliens and London’s trades and inhabitants.

The normative frameworks established by London’s guilds are represented most clearly in the dozens of sets of ordinances that were drawn up and in many cases presented to the city government for approval from the early fourteenth century onwards. This period of activity reflected the growth of formal structures within London’s crafts, which was itself both cause and consequence of the delegation by the mayor of the regulation of the trades to their leading representatives. Access to the freedom of the city via apprenticeship lay at the heart of this delegation.39 Craft ordinances often tended to focus on formal structures, especially apprenticeship and qualification for the franchise, and sought to describe and promote an idealized career path, as well as defining the membership of the craft in terms of citizenship rather than the wider body of inhabitants who practised particular trades. Yet this does not mean that we cannot use ordinances, despite their normative function and character, to shed light on the roles of non-citizens. Despite the anti-alien and anti-foreign rhetoric of petitions and legislation, the rules and regulations of crafts often reveal a more nuanced picture. In the case of aliens, if one looks closely at craft ordinances there are a few useful points that emerge. First, aliens and ‘foreigns’ were often lumped together, in legislative terms at least – perhaps not surprising given that the primary distinction being made was between freemen and everyone else. Guilds in London tended to define the ‘craft’ or ‘mistery’ in two ways, depending on the context: first, in a narrow sense to mean just the freemen, but also in a much broader sense to include anyone who practised the trade: citizen, alien or foreign.40 The Saddlers’ ordinances of 1364 are fairly typical:

Also that no alien or foreigner coming to the said city be allowed to keep house or shop, but that he be first examined by the four masters of the said mistery who are elected and sworn, whether he be able and sufficient to work in the said mistery or not. And if he be able and sufficient that they cause him to come before you to see if he can be acknowledged as good and sufficient for the common people as the franchise of the city demands, under the same penalty.

Also if any such be found to be not able or experienced in the said mistery, be he foreigner or alien, let him be compelled by the four masters aforesaid to serve other masters of the said mistery until he [be] able and sufficient for the common weal and also [become] free in the city, under penalty aforesaid.41

What is especially interesting – again in legislative/normative terms – is that the saddlers and other crafts specifically had mechanisms to allow aliens as well as foreigns to become freemen and to open shops, on the understanding that they should be examined as to their fitness to do so. In other words, there was, at that time at least, an acknowledgement of the involvement of aliens in manufacturing and a willingness to allow them to operate officially, subject to the scrutiny of the guilds’ wardens.

However, what was acceptable in the mid to late fourteenth century – a period of labour shortages and increasing demand for consumer goods – seems to have been less so by the end of the fifteenth century, when economic and demographic conditions had changed. Instead of labour shortages, the effects of economic recession, while not undermining London’s pre-eminence, meant that guilds were especially keen to preserve opportunities for their own members and took various measures to try and achieve this. Petitions against both aliens and foreigns became more common and matched the increase in rhetorical and legislative responses to migration seen in further alien subsidies and other measures. In 1484 parliament passed a statute which contained the complaint that alien craftsmen were arriving ‘in greate noumbre and more than they have used to doo in daies passed’ and attempted to impose a ban on the employment of aliens by fellow aliens and on aliens exercising any craft unless they were in the employ of subjects of the king.42 Petitions and ordinances submitted to the mayor and aldermen for approval in the 1480s and 1490s suggest that some guilds wished to go even further, reflecting a sense of anxiety about opportunities for apprentices and freemen which may well indicate that London’s population was beginning to grow again after a century of stagnation. Thus, the waxchandlers’ ordinances of 1488 stated simply that: ‘No foreyn or alien to be set on work in the Craft’.43 The hurers (cap-makers) took a similar view: ‘That no freeman of the Fellowship set an alien to work or to buy or sell in his shop, under penalty of 6s 8d’.44

Having gained a sense of how guilds formally regarded the work of aliens, and how that changed over time, we can now look in more detail at what their records tell us about the activities of aliens within particular crafts. The focus here is on two trades in which, as we have seen, aliens were especially numerous in the subsidy records and, crucially, for which extensive guild records survive: the London goldsmiths and tailors. The Goldsmiths in London were very closely associated with the aliens, both at the level of the royal court and in the city and country more generally. They were prized for their skills in working precious metals and as a result the guild made considerable efforts to reconcile the need to integrate them into networks of production (and indeed into the guild itself ), with the need to ensure that they did not threaten opportunities for native-born servants, apprentices and freemen.45 The Tailors were one of London’s largest and most ubiquitous trades, providing clothing for all levels of society, from fine robes for courtiers down to second-hand clothing sold on stalls in London’s markets. The king’s tailor in the later middle ages had often been an alien, with Parisian tailors being especially popular, though native-born tailors were also appointed to that office.46 Away from the royal court, as we have seen, it is clear from the alien subsidy rolls of 1483 and the records of the guild itself that alien labour and production formed a significant element in the clothing industry of late medieval London. With both the Goldsmiths and Tailors we have a combination of legislative records establishing the kind of normative frameworks with which we are perhaps most familiar, but also very detailed account and minute books which provide more nuanced insights into the ways in which regulations were, or were not, put into practice over time. The sources need to be treated carefully as they are not immune to the institutional perspectives and assumptions that come out more clearly in legislative sources, but they have much to offer, nonetheless. The same combination exists for some other guilds, the Brewers being the most obvious example of a craft with a significant alien element in the workforce. Alien brewers represented new skills and a new product – beer rather than ale – which remained associated with aliens well into the sixteenth century. Judith Bennett has drawn attention to the distinctive employment and service patterns of the alien beer brewers, in which male servants predominated, unlike the ale brewing workshops, which had a greater proportion of female servants. This both represented the importation of practices from the Low Countries, but also reflected the gender and age balance of migration more generally: relatively young and male in character. But she also noted, interestingly, that some alien brewers were becoming assimilated in the London Brewers’ guild: in 1436, for example, a number of wealthy alien brewers contributed substantial sums for a guild levy raised to provide funds for troops to relieve the town of Calais, besieged by Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy. This may partly have been a way for alien brewers to demonstrate their loyalty to the crown at a time when it was being questioned: the same year rumours had been spread in London about the unwholesome nature of beer as a ‘Dutch’ product.47 Nonetheless, it is one of several cases in which groups of aliens interacted with London guilds for mutual support and which should be set alongside instances of conflict, monitoring and exclusion.48

The records of the Goldsmiths and Tailors contain the names of dozens of alien craftsmen for the late fourteenth to early sixteenth centuries. Relatively few of these individuals are found in the alien subsidy records – partly a reflection of the infrequency of the subsidies themselves, but probably also of the mobility and transience of the alien population of London; and of patterns of service and employment within these trades which are difficult to reconstruct with snapshot sources. Broadly speaking, aliens appear in the records of these two guilds in two ways. First, they were fined by the guild for contravening ordinances of various kinds, whether to do with the quality of workmanship or other offences. Second, and especially in the Goldsmiths’ guild, aliens appeared swearing oaths or paying fees that allowed them to participate in different ways in the craft, for instance by registering servants or opening shops.49 Aliens were also fined for failing to observe those requirements. These broad categories remind us again of the ‘institutional lens’ through which we are looking, so care is needed when assessing this large quantity of information. Nonetheless, some notable patterns are visible.

The Goldsmiths, on the other hand, were usually much more explicit about these differences and used terms such as ‘stranger’, ‘dutchman’ or ‘alien’ far more often, although again there are exceptions.50 It would be interesting to know why this was. It could simply be because alien goldsmiths were less numerous than tailors and so easier to keep tabs on in terms of names, locations and nationalities – the Tailors quite often did not give names, for example, whereas the Goldsmiths mostly did. It could also be something to do with the distinctiveness or otherwise of the skills which aliens in these two crafts brought with them: possibly tailoring skills were more ‘generic’ outside the senior echelons of the trade and hence aliens and foreigns had much more in common, whereas alien goldsmiths were especially highly prized for their skills, whether in London or at the royal court.51

The prominence of aliens in the clothing industry in London is well attested in the records of the Tailors’ guild and in other sources, not just in the alien subsidy rolls but also in the few surviving wills of aliens and in wardmote and Church court records. As with other measures taken by the guilds and the city, one can see attempts to differentiate and limit the roles of aliens, while at the same time there is an implicit acknowledgement of interdependence. In terms of their official strategy, the primary (and ambitious) aim of the London Tailors’ guild seems to have been to ‘segment’ clothing manufacturing in the city by trying to stop non-citizens, and especially aliens, from making new clothing and forcing them to concentrate on refurbishing old clothes. This was not a new idea and it related in part to concerns in the clothing and textile industries (and others too) about the mixing of old and new materials.52 The separation of new and old commodities to avoid deceiving customers was reflected in a judgment made by the mayor and aldermen in 1409 that formally gave the Cordwainers the right to make new shoes, with the Cobblers restricted to refurbishing old shoes. Detailed specifications were laid down about the mixing of new leather with old, for example when putting a new sole on an old shoe. Interestingly, the judgment included the names of thirteen cobblers, divided into two groups of six English cobblers and seven aliens.53 The occupational information collected by the England’s Immigrants project has more than twice as many references to cobblers as to cordwainers – and, in fact, together these two shoemaking crafts constitute the largest cluster of occupational designations. It may well have been the case that aliens in the shoemaking industry were defined more closely by the second-hand trade rather than new work. In this and other cases, the guild structure in London reflected divisions between trades that were much more problematic in practice than in theory. The Tailors, by contrast, regulated the manufacture of both new and refurbished clothes – although that only dealt with the jurisdictional issue, not the concern about deception and confidence. Despite the practical challenges of implementing this policy of segmentation in the clothing trade, steps were taken by the Tailors to enforce it. Indeed, the overwhelming majority of fines the guild extracted from aliens in the fifteenth century were for ‘new work’, with very few relating to other aspects of the quality of the goods made and sold. For example, in 1427 a fine of 12d was received from ‘Un dutyschman in birchenlane for [making] a new doublet’.54 The guild tended to use the word ‘foreyn’ to denote unfree status generally and so it is not easy to separate out the aliens. Nonetheless, it is likely that many aliens were among those ‘foreyns’ fined for new work: in 1432–33, for example, 40d was extracted from ‘un forein in holborn pur faisur de nove werke diversis foitz’. The addition of a lining of ‘nove bokeram’ to an old gown cost one botcher 2s in 1425–6.55 It is worth noting, also, that the geographical distribution of these alien tailors was broad: although there were a number located on the eastern fringes of the city, others were identified as living in areas as diverse as Holborn, St. Margaret Pattens, Aldersgate, Thames Street, Dowgate, Fenchurch Street and elsewhere, in addition to unspecified taverns and hostels.56

There is another point of contrast here with the Goldsmiths, whose fines were much more likely to result from the detection of poor-quality workmanship – not surprising, given the relative value of the products and the high skill-levels involved. In the early 1430s fines were extracted from a number of alien goldsmiths, including two ‘at le Horn’, ‘Joanne, Duchman in le spitelle’ and ‘une frensshman in le Tour’.57 In 1441–2 Henry Luton, ‘dutchman’, was fined for making a sub-standard collar for the duke of Gloucester.58 Poor quality clothing, on the other hand, could always be sold to someone, as long as the customer was not deliberately deceived by, for example, the mixing of old and new materials: the famous ballad ‘London Lyckpeny’ sees the narrator losing his hood to a thief outside Westminster Hall before finding it again on a stall in Cornhill ‘where was mutch stolen gere’.59 The roles of aliens within trades were therefore connected with characteristics such as product differentiation and the role of the consumer.

As we have seen, ordinances and petitions from the guilds suggest that their own members frequently employed skilled alien workers, whether because they were cheaper or because they had different or better skills, or a combination of the two. The alien subsidy rolls testify to the large number of alien servants in London in the later middle ages; and many of these would have worked with native citizen craftsmen, despite the tendency for leading alien goldsmiths, as well as other migrant craftsmen, to employ fellow aliens. Both the Tailors and the Goldsmiths, despite some of their ordinances and public pronouncements, set in place mechanisms to try to integrate aliens into their trades – an implicit recognition of the significance of their work and skills and, one could argue, of the need to allow guild members some flexibility in expanding their businesses and developing new products. In the case of the Goldsmiths this integration was carefully structured: as early as 1368 an alien goldsmith arriving in London was meant to spend seven years as a servant before being allowed to open a shop or become enfranchised and further requirements were introduced over the next century.60 There was also much more of an emphasis in the Goldsmiths’ records on aliens as masters of their own workshops than was the case in other guilds: substantial fees were paid by aliens wanting to run businesses and they had to appear before the wardens to swear an oath. In 1409, for example, John de Ghent and three other aliens came before the wardens and swore on a book to keep all the ordinances of the craft.61 In most years covered by the fifteenth-century accounts there were three or four licences to trade granted each year in return for fees and oath swearing. The Goldsmiths had special oaths to be sworn by ‘Dutchmen’ which required them to take on English apprentices and not to employ other aliens or foreigns without permission. This says something about the delicate line that some guilds, at least, had to tread when they were dependent to a significant extent on alien skills and labour, but were under pressure to safeguard opportunities for native English apprentices and servants.62 A few were even admitted to the freedom of the city, paying very hefty fines to the Goldsmiths for the right to be presented: in 1432–3 Godard Sotte, ‘Dutchman’, took the oath and paid the extraordinary sum of £50 to be a freeman.63 The relatively small size of the goldsmiths’ craft seems to have allowed the guild to have a greater knowledge of, and confidence in, some of the aliens who worked in the trade. In February 1434 the guild passed an ordinance which revealed concerns about the distribution of substandard gold and silver by aliens. Their solution was to give the names of six trustworthy aliens, three of whom lived in Southwark, with whom guild members could buy and sell raw materials.64 As a result, many alien goldsmiths were, like their counterparts in the brewing industry, regarded as quasi-members of the guild: the Goldsmiths also contributed to the 1436 levy for Calais; and in their case more than half the £34 raised came from ‘dutchmen’ in London, Southwark and Westminster – possibly, like the alien brewers, as a demonstration of loyalty to the crown. Therefore we have at least two cases in which alien craftsmen collectively contributed to guilds’ civic obligations.65 This suggests that the Goldsmiths, despite some concerns about competition and regulation, did indeed operate what Reddaway and Walker termed a policy of ‘quiet absorption’ of immigrants into the trade: in the 1450s and 1460s fifteen aliens presented thirty-two apprentices, mostly also aliens by origin.66

There are some similarities with the tailoring industry. Some aliens became freemen via the Tailors’ guild: in 1427–8, for instance, John Chicheyard of Brabant paid £13 6s 8d and James Florence of Utrecht £18 to be freemen by redemption; the usual fee for English tailors was £3.67 Again, they were relatively few in number and the emphasis was much more on selling licences to practice the trade, although no oaths had to be sworn. Like goldsmiths, alien tailors were also granted licences to hold shops and to employ a specified number of servants, though there seems to have been more flexibility in terms of numbers than with the alien goldsmiths, who were often restricted to one servant. The main difference is a greater emphasis on the employment of servants and journeymen by citizen tailors, which seems to have been ubiquitous and suggests a dependence on alien and foreign labour and skills. In 1425–6, for example, a large number of ‘dutch foreign servants’ were registered by freemen of the guild at the fairly hefty cost of 5s each.68 In some cases fees were paid to employ alien servants for a specified number of weeks, but we can also see certain London tailors appearing every year to re-register the same alien servants – indicating continuity as well as transience in the alien population, something which Bolton and Lutkin also noted.69 Sometimes the aliens themselves paid a fee to work as journeymen, indicating the perceived advantages of association with the formal craft even at that level: in 1432–3 a ‘Dutchman’ in Lombard Street paid 8d to be covenanted with Alexander Farnell, a leading member of the guild who had been master in 1424–5.70

A range of terms was used in the Tailors’ records to describe these aliens, with ‘foreign’ being the most common. Some are given a ‘nationality’ – Dutch, Fleming, French, Norman – or a place of origin such as Brabant or Almain. In combination we sometimes find occupational descriptors: the term ‘shaper’ is used frequently by the Tailors, a direct reference to the skills needed to cut cloth for clothing, while stitching skills were reflected in the label ‘sower’. ‘Botchers’ were those who refurbished and sold second-hand clothing and were extremely numerous, as the guild sought to ensure that they stuck to their allocated market. Equally common (and interesting) is the frequent use of the term ‘galleyman’, used to describe Italians who came to London on galley ships. We know from the city records that galleymen were traders who arrived on ships in the port of London and sold small wares of various kinds in ‘their accustomed shops’.71 There was a similar presence in Southampton, as Alwyn Ruddock has noted. In both Southampton and London tailors seem to have been especially numerous among the galleymen: in 1406 the Southampton tailors asked the mayor for protection and as a result all foreign and galley tailors were forbidden to set up shop or to work in the town until they made a payment to the master of the craft.72 Similarly in London, the guild required galleymen to obtain licences to make and sell clothing and to register their servants. In the 1420s, for example, the records generally list payments from the galleymen as a group, with the total fees received from them of between £3 and £7 per annum, but increasingly we have the names of individuals such as Nicholas de Georgio ‘galyman shaper’, who paid fees for himself and his servants in 1455.73 Some galleymen appear to have been regular visitors to London, or else spent months or years in the city: in September 1488 Benedict de Cena, galleyman, paid 4s for two months for himself and his family and 2s for a further four months in November. He may then have left London, but in April 1491 he was back and agreed to pay 6d a week for two shops on an ongoing basis. Nicholas de Zachary paid for himself and two servants in 1463 and then again in 1465.74 It seems from the Tailors’ records that galleymen did not just trade with goods they brought with them: apart from licences to buy and sell, the guild also fined many of them for making new clothes of various kinds as part of its drive to keep aliens to the second-hand trade.75 There are also references to licences granted to aliens during ‘le temps dez galeys’ or ‘le galetyme’ – indicating that the arrival of fleets in London at particular times of the year heralded an influx of potential competitors, as well as increasing the supply of alien skilled labour.76 However, judging from the frequency with which some individuals appear in the guild’s records, many galleymen were in fact semi-permanent residents – perhaps staying for anything from a few months to a few years. Where did they live? Their generally temporary residence means that few, if any, would have been picked up in the alien subsidy rolls. John Stow, writing at the end of the sixteenth century, described Mincheon (now Mincing) Lane in London as follows: ‘In this lane of olde time dwelled diuers strangers borne of Genoa and those parts, these were commonly called Galley men, as men that came vppe in the Gallies, brought vp wines and other merchandises which they landed in Thames street, at a place called Galley key’.77 We do not know whether Mincing Lane was a hub for galleymen in the fifteenth century, as few locations are mentioned for them, but, as we have seen, Tower ward was one of the areas where aliens were especially well represented in the alien subsidy records (see Figures 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3). An inventory of the church of All Hallows Barking, in the east of the city, from 1452 listed ‘ij candelstikkes of siluer’, ‘crosse plated with siluer and the fote of coper’, ‘ij chalys marked vppon the patyns that oon wt B and tht other with D’, ‘ij. clothes of gold’ and ‘j baner of white tartaryn wt an ymage of our lady’ – all said to be ‘of the yifte of the Galymen’, suggesting connections with areas further east.78

Throughout these records anti-alien feeling and the rhetoric of exclusion and control are never far away – and indeed without it the documentary sources would be rather sparse, given the efforts of the Goldsmiths and Tailors to regulate the activities of aliens. What this essay has tried to suggest, however, is that we can use records such as these to try to describe more comprehensively the roles played by aliens within some of the city’s crafts, thereby contributing to a wider view of urban production and distribution that extends beyond the guilds and citizens. The frequent complaints made by guilds about aliens to the city government are not incompatible with this; and in deciding how far to regulate their trades in practice, the guilds had to grapple with internal dynamics and aspirations which were sometimes contradictory. We can see, for example, that aliens were especially prominent, and perhaps embedded, within certain trades and that in different ways guilds such as the Brewers, Goldsmiths and Tailors managed to tolerate or accommodate them – acknowledging the demand for their skills and labour services, but at the same time responding to pressure from those concerned about competition. More research is needed in order to contextualize and supplement these findings. Was it the case, for example, that crafts which were less dependent on alien skills and labour could afford to be less flexible and pragmatic in the enforcement of legislative restrictions? Aliens, whether temporary or settled, were very much part of the world of production, exchange and consumption in London and there is more to be learned about their activities within crafts and neighbourhoods in the city.

Endnotes

- J. L. Bolton, The Alien Communities of London in the Fifteenth Century: the Subsidy Rolls of 1440 and 1483–4 (Stamford, 1998), pp. 8–9, revising S. L. Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London in the 15th century’, in Studies in London History presented to P. E. Jones, ed. A. E. J. Hollaender and W. Kellaway (London, 1969), pp. 251–74.

- Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, pp. 251–3.

- See, e.g., D. Pearsall, ‘Strangers in late-fourteenth-century London’, in The Stranger in Medieval Society, ed. F. R. P. Akehurst and S. C. Van D’Elden (Minneapolis, Minn., 1997), pp. 46–62.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 8–9; England’s Immigrants <http://www.englandsimmigrants.com> [accessed 17 Aug. 2018].

- See especially Resident Aliens in Later Medieval England, ed. W. M. Ormrod, N. McDonald and C. Taylor (Tournhout, 2017); and W. M. Ormrod, B. Lambert and J. Mackman, Immigrant England, 1300–1550 (Manchester, 2018). I am grateful to Bart Lambert for sharing the proofs of this important new contribution before publication.

- M. E. Bratchel, ‘Alien merchant communities in London, 1500–50’ (unpublished University of Cambridge PhD thesis, 1975); M. E. Bratchel, ‘Italian merchants’ organisation and business relationships in early Tudor London’, Jour. Eur. Econ. Hist., vii (1978), 5–32; M. E. Bratchel, ‘Regulation and group consciousness in the later history of London’s Italian merchant colonies’, Jour. Eur. Econ. Hist., ix (1980), 585–610; H. Bradley, ‘The Italian community in London, 1350–1450’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 1992); H. Bradley, ‘The Datini factors in London, 1380–1410’, in Trade, Devotion and Governance, ed. D. J. Clayton, R. G. Davies and P. McNiven (Stroud, 1994), pp. 55–79; The Views of the Hosts of Alien Merchants 1440–1444, ed. H. Bradley (London Rec. Soc., xlvi, 2012). See also Matthew Payne’s essay in the present volume.

- G. A. Holmes, ‘Anglo-Florentine trade in 1451’, Eng. Hist. Rev., cviii (1993), 371–84; J. L. Bolton, ‘London merchants and the Borromei bank in the 1430s: the role of local credit networks’, in The Fifteenth Century X. Parliament, Personalities and Power: Papers Presented to Linda S. Clark, ed. H. Kleineke (Woodbridge, 2011), pp. 53–73.

- E.g., S. Jenks, ‘Hansische Vermächtnisse in London, c.1363–1483’, Hansische Geschichtsblätter, civ (1986), 35–111; T. H. Lloyd, England and the German Hanse, 1157–1611 (Cambridge, 1991).

- LMA, COL/CC/01/01/007, fos. 178r–v.

- J. L. Bolton, ‘London and the peasants’ revolt’, London Jour., vii (1981), 123–4; E. Spindler, ‘Flemings in the peasants’ revolt, 1381’, in Contact and Exchange in Later Medieval Europe: Essays in Honour of Malcolm Vale, ed. H. Skoda, P. Lantschner and R. J. L. Shaw (Woodbridge, 2012), pp. 59–78; B. Lambert and M. Pajic, ‘Immigration and the common profit: native cloth workers, Flemish exiles, and royal policy in fourteenth-century London’, Jour. Brit. Stud., lv (2016), 633–57 (modifying some of Spindler’s conclusions); J. L. Bolton, ‘The city and the crown, 1456–61’, London Jour., xii (1986), 11–24. For recent work on ‘Evil May Day’, see S. McSheffrey, ‘Evil May Day, 1517: prosecuting anti-immigrant rioters in Tudor London’, Legal Hist. Miscellany, xxx (2017) <https://legalhistorymiscellany.com/2017/04/30/evil-may-day-1517> [accessed 3 Jan. 2018].

- Ormrod, Lambert and Mackman, Immigrant England, pp. 32–5, 142; Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 2–7; J. L. Bolton, ‘London and the anti-alien legislation of 1439–40’, in Ormrod, McDonald and Taylor, Resident Aliens, pp.33–50; J. Lutkin, ‘Settled or fleeting? London’s medieval immigrant community revisited’, in Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of J. L Bolton, ed. M. Allen and M. Davies (London, 2016), pp. 137–55; M. Davies, ‘Lobbying parliament: the London companies in the fifteenth century’, Parliamentary Hist., xxiii (2004), 136–48.

- Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, pp. 262–3; Bolton, ‘Alien communities’, pp. 39–40.

- E.g., E. M. Veale, ‘Craftsmen and the economy of London in the fourteenth century’, in The Medieval Town: a Reader in English Urban History 1200–1540, ed. R. Holt and G. Rosser (London, 1990), pp. 120–40; C. E. Berry, ‘Margins and marginality in fifteenth-century London’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 2018); M. Davies, ‘Citizens and “foreyns”: crafts, guilds and regulation in late medieval London’, in Between Regulation and Freedom:Work and Manufactures in European Cities, 14th–18th Centuries, ed. A. Caracausi, M. Davies and L. Mocarelli (Newcastle, 2018), pp. 1–21.

- Ormrod, Lambert and Mackman, Immigrant England, ch. 10, ‘Integration and confrontation’.

- Bolton, ‘London merchants and the Borromei bank’; Bradley, Views of the Hosts.

- E.g., M. Boone, ‘The desired stranger: attraction and expulsion in the medieval city’, in Living in the City: Urban Institutions in the Low Countries, 1200–2010, ed. L. A. C. J. Lucassen and W. H. Willems (New York, 2012), pp. 32–45; Gated Communities? Regulating Migration in Early Modern Cities, ed. B. De Munck and A. Winter (Farnham, 2012).

- E. Spindler, ‘Between sea and city: portable communities in late medieval London and Bruges’, in London and Beyond: Essays in Honour of Derek Keene, ed. M. Davies and J. Galloway (London, 2012), pp. 181–200.

- J. Colson, ‘Alien communities and alien fraternities in later medieval London’, London Jour., xxxv (2010), 111–43.

- E.g., the work of Paul Griffiths, such as Lost Londons: Change, Crime and Control in the Capital City, 1550–1660 (Cambridge, 2008).

- This was in the context of a discussion about the afterlife of that migrant par excellence, Richard Whittington (J. Robertson, ‘The adventures of Dick Whittington and the social construction of Elizabethan London’, in Guilds, Society and Economy in London, 1400–1800, ed. I. A. Gadd and P. Wallis (London, 2002), pp. 51–66). For Whittington’s career, see especially C. M. Barron, ‘Richard Whittington: the man behind the myth’, in Hollaender and Kellaway, Studies in London History, pp. 197–248.

- Two Early London Subsidy Rolls, ed. E. Ekwall (Lund, 1951), pp. 71–81; CPMR 1364–1381, pp. vii–lxiv; S. L. Thrupp, The Merchant Class of Medieval London (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1962), p. 50. For the rights and privileges of London citizens, see C. M. Barron, London in the Later Middle Ages: Government and People 1200–1500 (Oxford, 2004), pp. 38, 77.

- E.g., A. F. Sutton, ‘Two dozen and more silkwomen of fifteenth-century London’, Ricardian, xvi (2006), 46–58; J. M. Bennett, ‘Women and men in the brewers’ gild of London ca. 1420’, in The Salt of Common Life: Individuality and Choice in the Medieval Town, Countryside and Church: Essays Presented to J. Ambrose Raftis on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday, ed. E. B. DeWindt (Studies in Medieval Culture, xxxvi, Kalamazoo, Mich.,1995), pp. 181–232.

- L. B. Luu, Immigrants and the Industries of London, 1500–1700 (London, 2005).

- E.g., S. R. Epstein and M. Prak, ‘Introduction’, in Guilds, Innovation and the European Economy, 1400–1800, ed. S. R. Epstein and M. Prak (Cambridge, 2008), pp. 1–24, at pp. 10, 23; Technology, Skills and the Pre-Modern Economy in the East and the West: Essays Dedicated to the Memory of S. R. Epstein, ed. M. Prak and J. Luiten van Zanden (Leiden and Boston, Mass., 2013).

- D. Keene, ‘English urban guilds, c.900–1300: the purposes and politics of association’, in Guilds and Association in Europe, 900–1900, ed. I. A. Gadd and P. Wallis (London, 2006), pp. 3–26.

- Veale, ‘Craftsmen and the economy of London’. See also S. Rees Jones, ‘Household, work and the problem of mobile labour: the regulation of labour in medieval English towns’, in The Problem of Labour in Fourteenth-Century England, ed. J. Bothwell, P. J. P. Goldberg and W. M. Ormrod (York, 2000), pp. 133–53.

- Davies, ‘Citizens and “foreyns”’, p. 121.

- See the England’s Immigrants database <https://www.englandsimmigrants.com/> [accessed 10 Feb. 2019].

- Lutkin, ‘Settled or fleeting?’.

- Lutkin, ‘Settled or fleeting?’, p. 139.

- On the variations between the subsidy returns, see Lutkin, ‘Settled or fleeting?’

- Bolton, Alien Communities; Lutkin, ‘Settled or fleeting?’

- For the residence patterns of Italian merchants, see Bradley, ‘Italian community in London’, pp. 13–62.

- Lutkin, ‘Settled or fleeting?’, p. 150.

- Barron, London in the Later Middle Ages, p. 66.

- J. Lutkin, ‘Goldsmiths and the English royal court 1360–1413’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 2008); J. Stratford, Richard II and the English Royal Treasure (Woodbridge, 2013).

- J. M. Bennett, Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600 (New York and Oxford, 1996), pp. 80–1. See also Ormrod, Lambert and Mackman, Immigrant England, pp. 127–39, for detailed discussion of the findings of the England’s Immigrants project.

- These patterns are discussed in depth in Ormrod, Lambert and Mackman, Immigrant England, pp. 127–33.

- CPMR 1364–81, pp. ii, xxviii; E. M. Veale, ‘The “great twelve”: mistery and fraternity in thirteenth-century London’, Hist. Research, lxiv (1991), 237–63; M. Davies, ‘Crown, city and guild in late medieval London’, in Davies and Galloway, London and Beyond, pp. 247–68, at pp. 251–3.

- M. Davies, ‘Governors and governed: the practice of power in the Merchant Taylors’ Company in the fifteenth century’, in Gadd and Wallis, Guilds, Society and Economy, pp. 67–84.

- Cal. Letter Bks. G, 1352–1374, p. 142.

- Bolton, Aliens, pp. 35–40; Statutes of the Realm … [1101–1713], ed. A. Luders et al. (11 vols., London, 1810–28), ii. 489–93; ‘Richard III: January 1484’, in Parliament Rolls of Medieval England, ed. C. Given-Wilson et al. (Woodbridge, 2005); British History Online<http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/parliament-rolls-medieval/january-1484> [accessed 3 Jan. 2019].

- Cal. Letter Bks. L, p. 254.

- Cal. Letter Bks. L, p. 264.

- T. F. Reddaway and L. E. M. Walker, The Early History of the Goldsmiths’ Company, 1327–1509 (London, 1975); J. Lutkin, ‘Luxury and display in silver and gold at the court of Henry IV’, in The Fifteenth Century IX. English and Continental Perspectives, ed. L. Clark (Woodbridge, 2010), pp. 155–78; Ormrod, Lambert and Mackman, Immigrant England, pp. 127–39.

- M. Davies and A. Saunders, The History of the Merchant Taylors’ Company (Leeds, 2004). On royal tailors, see, e.g., A. F. Sutton, ‘George Lovekyn, tailor to three kings of England, 1470–1504’, Costume, xv (1981), 1–12.

- Cal. Letter Bks. K, p.206. I am grateful to Joshua Ravenhill for this reference. For the ramifications of the political turmoil, see Ormrod, Lambert and Mackman, Immigrant England, pp. 140–1.

- Bennett, Ale, Beer and Brewsters, pp. 80–1.

- The analysis which follows draws especially on the Tailors’ accounts, which run from 1398 to 1484 (with small gaps); and the accounts and minute books of the Goldsmiths. See CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, 002, 003; Wardens’ Accounts and Court Minute Books of the Goldsmiths’ Mistery of London 1334–1446, ed. L. Jefferson (Woodbridge, 2003), passim; Reddaway and Walker, Goldsmiths.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, passim.

- Lutkin, ‘Luxury and display’; Lutkin, ‘Goldsmiths and the English royal court’; Reddaway and Walker, Goldsmiths; Stratford, Richard II and the English Royal Treasure.

- Davies, ‘Citizens and “foreyns”’, p. 19.

- Cal. Letter Bks. I, pp. 73–4.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fo. 181.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fos. 159, 235.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, passim.

- Possibly the environs of the Tower of London, such as the precincts of St. Katherine’s hospital, where ‘Dutch’ aliens are known to have congregated to avoid scrutiny by the city and the guilds. I am grateful to Joshua Ravenhill for this information.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, pp. 461, 521.

- J. Lydgate, ‘London Lyckpeny’, in The Oxford Book of Late Medieval Verse and Prose, ed. D. Gray (Oxford, 1985), pp. 16–9.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, p. 113.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, p. 335.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, p. 363.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, p. 457.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, p. 461.

- Jefferson, Wardens’ Accounts, pp. 481, 485–7.

- Reddaway and Walker, Early History of the Goldsmiths, p. 128.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fo. 182.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fo. 160v.

- S ee especially Lutkin, ‘Settled or fleeting?’, pp. 150–3.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fo. 236v.

- Cal. Letter Bks. L,p. 278.

- S ee A. A. Ruddock, ‘The merchants of Venice and their shipping in Southampton in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries’, Papers and Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club & Archaeological Society, xv (1943), 274–91; A. A. Ruddock, ‘Alien merchants in Southampton in the later middle ages’, Eng. Hist. Rev., lxi (1946), 1–17; A. A. Ruddock, ‘The Flanders galleys’, History, xxiv (1940), 311–17, at p. 314 (for the 1406 incident). I am grateful to Joshua Ravenhill for these references.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fos. 55, 61, 68, 73, 81, 89, 95, 100v, 107v, 117v, 125v, 133, 142, 151, 159, 181.

- The Merchant Taylors’ Company of London: Court Minutes 1486–1493, ed. M. Davies (Stamford, 2000), pp. 114, 122, 181; LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fos. 242, 257. He was possibly related to the Genoese merchant Jacopo Zachary (listed wrongly as a Florentine), in a tax assessment of 1464 <https://www.englandsimmigrants.com/person/24124> [accessed 18 Aug. 2018]. I am grateful to Bart Lambert for this information.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, 002.

- LMA, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/001, fo. 181.

- A Survey of London by John Stow, ed. C. L. Kingsford (2 vols., Oxford, 1908), i. 129–38 (Tower ward).

- Survey of London, xii, The Parish of All Hallows Barking. Part 1: the Church of All Hallows, ed. L. J. Redstone (London, 1929), pp. 70–5.

Chapter 6 (119-147) from Medieval Londoners: Essays to Mark the Eightieth Birthday of Caroline M. Barron, edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer (University of London Press, 10.31.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.