Critical consumption of social media news would have protective effects on individuals’ perceptions and decision-making.

By Dr. Porismita Borah

Professor of Communication

Edward R. Murrow College of Communication

Washington State University

By Xizhu Xiao

PhD Student in Communication

Edward R. Murrow College of Communication

Washington State University

By Yan Su

PhD Student in Communication

Edward R. Murrow College of Communication

Washington State University

Abstract

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation has been circulating on social media and multiple conspiracy theories have since become quite popular. We conducted a U.S. national survey for three main purposes. First, we aim to examine the association between social media news consumption and conspiracy beliefs specific to COVID-19 and general conspiracy beliefs. Second, we investigate the influence of an important moderator, social media news trust, that has been overlooked in prior studies. Third, we further propose a moderated moderation model by including misinformation identification. Our findings show that social media news use was associated with higher conspiracy beliefs, and trust in social media news was found to be a significant moderator of the relationship between social media news use and conspiracy beliefs. Moreover, our findings show that misinformation identification moderated the relationship between social media news use and trust. Implications are discussed.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation has been circulating on social media, and multiple conspiracy theories have since become quite popular, such as the one claiming that the 5G mobile network is accountable for the COVID-19 spread (Ahmed et al., 2020). Defined as a “tendency to explain the cause of significant events as a secret malevolent plot” (Stojanov, 2015: 251), conspiracy beliefs can be extremely dangerous since such beliefs can prevent individuals from establishing positive intentions and behaviors (Jolley and Douglas, 2014a). The negative consequences of conspiracy beliefs are especially alarming at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has swept across the world, killing millions of people. Indeed, recent research has found a negative relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and protective health behaviors (e.g. Freeman et al., 2020). Beliefs in conspiracy theories also reduced individuals’ compliance with the government health guidelines such as social distancing, which posed a grave danger to public health (e.g. Bierwiaczonek et al., 2020).

Social media are often blamed for spreading misinformation and facilitating conspiracy beliefs (AVAAZ, 2020; Garrett, 2019; Vraga et al., 2020). For instance, incorrect posts about the Zika virus were more popular on social media than the accurate information (Sharma et al., 2017). Using social media as an information source was also shown to be positively associated with greater beliefs in COVID-19-related conspiracy theories (Allington et al., 2020). While prior research has endeavored to understand the impact of social media use on conspiracy beliefs (e.g. Allington et al., 2020), much remains unknown in terms of the pathway from social media news consumption to conspiracy belief formation. Specifically, an examination of influence of trust is often missing even though being skeptical with less blind trust in media information may be critical in helping combat the impact of misinformation (e.g. Vraga and Tully, 2019). The level of trust in social media news varied significantly across studies. For example, some researchers found that social media news consumers are skeptical about the news encountered (Shearer and Grieco, 2019; Shearer and Matsa, 2018); while some suggested that individuals consider social media highly credible and trustworthy news sources (Bantimaroudis et al., 2020; Mitchell et al., 2019). As such, whether the trust of social media news use would moderate the relationship between social media news consumption and conspiracy belief formation warrants further investigation.

More importantly, scholars indicated that improving critical consumption of news is imperative since the ability to discern misinformation and disinformation could mitigate the negative influences of conspiracy theories on society (e.g. Douglas et al., 2016; Jones-Jang et al., 2019; Vraga et al., 2020). Although many individuals reported having encountered and identified misinformation on social media (Jurkowitz and Mitchell, 2020; Shearer and Grieco, 2019; Shearer and Matsa, 2018), little empirical evidence exists examining its effects on decision-making. That is, whether misinformation identification would influence the relationship between social media news use and conspiracy belief formation remains under-explored (e.g. Jones-Jang et al., 2019).

Thus, in addressing the voids in the literature, we conducted a US national survey for three main purposes. First, we examined the association between social media news consumption and conspiracy belief formation. To strengthen external validity, we tested two types of conspiracy beliefs—one consists of conspiracy beliefs specific to COVID-19 (e.g. The COVID-19 is a weapon of the biological warfare used by foreign countries) and the other contains long-standing conspiracy beliefs (e.g. the United States’ moon-landing and the 911 attack are hoaxes). Second, we investigated the influence of an important moderator, social media news trust, which has been overlooked in prior studies. Third, we further proposed a moderated moderation model by including misinformation identification. More specifically, we hope to understand whether enhancing literacy-related behaviors such as critical consumption of social media news would have protective effects on individuals’ perceptions and decision-making.

The Effects of Social Media News Use

As social media permeate peoples’ daily lives, individuals across the globe are experiencing drastic changes in the way they access and consume news. Specifically, the traditional pattern of news consumption (e.g. newspaper, radio, Television) has been changed by social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, which provide instant news updates and allow for rapid dissemination of information. Statistics showed that 49% of US adults use social media as a source of news (Statista, 2020). Globally, many countries reported continuous growth in the use of social media as news sources (Newman et al., 2018). As such, a large body of literature has investigated social media’s role in news consumption and its potential effects on individuals’ decision-making and behaviors (e.g. Fletcher and Nielsen, 2018; Huber et al., 2019).

On one hand, some scholars were thrilled about the positive influences, arguing that the egalitarian access and equality in information production and dissemination are conducive for the formation and maturation of deliberative democracy (Rishel, 2011). According to prior scholars, the defining characteristics of a deliberative democracy involve inclusion, political equality, reasonableness, and publicity (Rishel, 2011; Young, 2002), and the nature and functionalities of social media can enable the realization of these characteristics. For instance, Halpern and Gibbs (2013) suggested that social media such as Facebook expands “the flow of information . . . and enables more symmetrical conversation” (p. 1159), catalyzing online deliberation. Another benefit of social media news use pertains to its role in facilitating non-purposive and incidental news exposure (e.g. Fletcher and Nielsen, 2018; Yamamoto and Morey, 2019). Scholars pointed out that unintentional exposure to news information on social media is linked to a range of positive outcomes including more recognition and recall of news information, information seeking, better use of diverse news sources for information assessment, and active news engagement (e.g. Fletcher and Nielsen, 2018; Oeldorf-Hirsch, 2018).

On the other hand, many scholars have also lamented the negative ramifications of social media news use (e.g. Garrett, 2019; Goertzel, 2010; Jolley and Douglas, 2014a; Lewandowsky et al., 2015). They argued that due to the lack of gatekeepers, insufficient fact-checking systems, uncontrolled marketing incentives, and inadequate legal supervision, social media have generated a breeding ground on which conspiracy theories, dis- and misinformation have prevailed (Bastani and Bahrami, 2020; Hameleers et al., 2020 Vraga et al., 2020). Indeed, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, plenty of studies have already provided evidence that most of the prominent conspiracy theories were first generated and spread on social media (e.g. Pennycook et al., 2020; Kouzy et al., 2020). Allington et al. (2020), for instance, suggested that individuals who used social media as news or information sources had greater beliefs in COVID-19-related conspiracy theories; these individuals were also less likely to engage in recommended health-protective behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. These conspiracy theories are not only unfavorable for deliberative democracy but can also increase rejection of science and reluctance to engage in positive health and social behaviors such as preventive measures (e.g. Bastani and Bahrami, 2020; Goertzel, 2010; Jolley and Douglas, 2014a; Lewandowsky et al., 2015; Vraga et al., 2020). Against this backdrop, our examination of the role of social media news use in influencing people’s conspiracy theories about COVID-19 is much warranted.

Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories have been defined as the tendency to explain the causes of events, particularly important historical and social events, as covert and conscious actions by influential, organized, and malevolent groups (Byford, 2011; Douglas et al., 2016); these manipulative groups purposefully withhold the truth of these events from the public (Kim and Cao, 2016). For instance, popular conspiracy theories presume that the moon landing was faked by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); the 9/11 attack was carried out by certain officials within the American government; and moguls in the medical industry unscrupulously buried the causal linkage between vaccination and autism (Goertzel, 2010; Lewandowsky et al., 2013; Wood et al., 2012). Aided by the Internet and social media in particular, conspiracy theories have not only drawn public attention away from the true explanations of the events; more worryingly, they have also grown into “a mainstream paradigm through which many individuals try to make sense of the world” (Bantimaroudis et al., 2020: 118).

More recently, following the outbreak of COVID-19, conspiracy theories surrounding the pandemic have become rampant on social media. For example, widespread conspiracy theories presumptuously assumed that the COVID-19 pandemic was caused by electromagnetic waves transmitted by the 5G mobile network (Ahmed et al., 2020). According to a recent poll (Pew Research Center, 2020), 3 in 10 American people trusted the accusation that COVID-19 was made in a lab. Relatedly, many also believed that Bill Gates created the virus to either use the vaccines to implant tracking devices in people or to make money from vaccination (Lovelace, 2020); some also asserted that the pandemic is a part of Gates’ depopulation plans (Kelion, 2020).

Multiple studies have demonstrated consequences of beliefs in conspiracy theories (e.g. Goertzel, 2010). For example, Kim and Cao (2016) revealed that beliefs in government-related conspiracy theories induced both short-term and long-term cynicism and distrust toward the government. Jolley and Douglas (2014b) found that conspiracy beliefs regarding climate change significantly reduced individuals’ intention to engage in pro-environment activities. Likewise, exposure to conspiracy theories concerning anti-vaccination resulted in significantly lower intention to get vaccinated (Jolley and Douglas, 2014a). More importantly, once conspiracy beliefs are held, any measures to debunk and reduce them may not be as effective as expected (Stojanov, 2015; Wood, 2016).

In light of these consequences, scholars have examined factors associated with the increase of conspiracy beliefs among the public. Numerous studies have already suggested that frequent social media news use was associated with both conspiracy beliefs at large (e.g. Shin et al., 2018) and the COVID-19-related conspiracy theories (e.g. Allington et al., 2020). For instance, Shin et al. (2018) found that during the 2012 presidential election cycle, Twitter had contributed to the circulation of false information within homophilous follower networks. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Allington et al. (2020) also revealed that when people relied more heavily on social media for information seeking, they had a stronger tendency to believe in the COVID-19-related conspiracy theories than those who did not treat social media as the main information source.

With the help of the reviewed literature, we propose the first hypothesis:

H1. Higher social media news use is associated with greater beliefs in (a) general conspiracy theories and (b) COVID-19 conspiracy theories.

Social Media News Trust

Trust is broadly considered as the foundation of the social relationship (Coleman, 2012). Although the conceptualization of social media trust has various dimensions, including trust in news content, the news deliverer, and the media ownership (Turcotte et al., 2015; Williams, 2012), the current study concentrates on the perceived believability and trustworthiness of news on social media (Castillo et al., 2011; Wang and Mark, 2013). In other words, we operationalize social media news trust as the extent to which an individual believes that the news she or he consumed from social media platforms is trustworthy.

Social media news trust has been consistently affirmed to be a significant factor influencing various types of behaviors (e.g. Lin et al., 2016; Sterrett et al., 2019). For instance, Sterrett et al. (2019) found that stories shared by trusted, reputable outlets or individuals could trigger more viewers. In addition to consumptive behaviors, trust in social media content also has an impact on productive ones. Lin et al. (2016) found that the more people trust in social media content, the higher levels of online self-disclosure they had, because such perceived trustworthiness helps reduce perceived uncertainty and risks. Trust in social media content is also found to associate with perceptions of misinformation. As trust in mainstream media has reportedly been declining, people turned to online opinion leaders and their friends to vouch for information (Anspach and Carlson, 2020; Turcotte et al., 2015). However, due to the ease of use, the easier accessibility, and the low cost of information sharing, online social networks can hardly guarantee the legitimacy and credibility of news and information (Viviani and Pasi, 2017). Therefore, blind trust of social media content could stimulate misinformation herding (Anspach and Carlson, 2020). Indeed, multiple studies have confirmed that higher skepticism toward social media news is related to decreased misinformation and conspiracy beliefs (e.g. Karlsson et al., 2017; Nekmat, 2020).

In addition, scholars have confirmed that media trust can serve as a significant moderator to media effects, as shown in studies on agenda-setting, framing, and priming (e.g. Druckman, 2001; Ladd, 2004). Specifically, the extent to which people trust the media platform could vary the relationship between their exposure to the information and their responses, such as perception shaping, knowledge building, and participation mobilization (e.g. Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2018; Kaufhold et al., 2010). If a consumer perceived that the content deliverer, namely, the platform, is “objective, impartial, accurate, or unbiased,” the consumer might believe in the authenticity of the content as well as the mobilization power of the information (Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2018: 615). For instance, Tsfati (2002) found that the media’s agenda-setting effects were varied by audiences’ mistrustfulness of the media. Specifically, among those who were less likely to trust the media, the media’s influence in shaping audiences’ perceptions was weakened. Ardèvol-Abreu et al. (2018) found that the more people trust the media platform through which they consume information, the more likely they were mobilized by the information content to participate online. Similarly, Ladd (2004) also suggested that audiences who distrust the media were less likely to update their beliefs in response to media coverage. Taken together, decades of research have consistently lent evidence that people who trust the media would be more likely to accept media messages (Ladd, 2010). To understand the association between social media news use and conspiracy beliefs, it was pertinent to add social media news trust to the model. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2. Social media news trust moderates the association between social media news use and (a) general conspiracy theories and (b) COVID-19 conspiracy theories.

Misinformation Exposure and Identification

Misinformation and disinformation research have drawn significant attention from scholars over the years. We might not have all the answers about where false information originates and how this information might undermine democracies, but we do know that there is no shortage of false and misleading information (Weeks and Gil de Zúñiga, 2019). Misinformation is often defined as the false information that is circulated without the “disseminators’ knowledge” (Freelon and Wells, 2020: 1). Disinformation is defined as “all forms of false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented and promoted to intentionally cause public harm or for profit” (Freelon and Wells, 2020: 1).

Research in this area have examined the impact of misinformation and disinformation on politics (Guess et al., 2018; Weeks and Garrett, 2014), while others have studied the spread of false information (Bradshaw et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2018). The effects of corrective measures to fight misinformation and disinformation have also garnered attention from scholars (e.g. Lewandowsky et al., 2012; Vraga and Bode, 2017). Other studies have examined how political attitudes (Ecker et al., 2010; Nyhan and Reifler, 2010; Thorson, 2016) and media literacy (Chen et al., 2011; Vraga et al., 2020) might impact individuals’ misinformation perception. Thorson (2016) posited the crucial role played by political attitudes on misinformation perception, as a result of which individuals may continue to believe false information even after being corrected. “Misinformation continues to affect behavior, even if people explicitly acknowledge that this information has been retracted, invalidated, or corrected” (Ecker et al., 2010: 1087). Lazer et al. (2018) highlighted the importance of changes in online platforms to decrease the instances of exposure to misinformation as well as empowering individuals such that they can evaluate the information and identify misinformation and disinformation.

We think that to be able to combat false information, individuals will have to be aware that they have been exposed to inaccurate information. In that sense, identifying misinformation is perhaps the first step to stop falling prey to the dangers of false information. Media literacy scholars have long argued that increasing literacy, especially news literacy, helps in combating misinformation and conspiracy belief formation and spread (e.g. Craft et al., 2017; Vraga et al., 2020). However, some suggested no direct or positive protective effects of news literacy (e.g. Jones-Jang et al., 2019). Despite these mixed findings, prior research concurred that improving critical consumption of news by enhancing the ability to identify false information and assess the accuracy of information is crucial in the current digital world where misinformation is abundant (Craft et al., 2017; Jones-Jang et al., 2019). Therefore, the following research question is formulated:

RQ1. How does misinformation identification moderate the moderated relationship between social media news use and beliefs in (a) general conspiracy theories and (b) COVID-19 conspiracy theories?

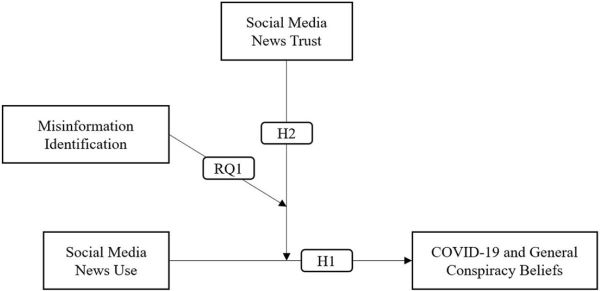

In light of the reviewed literature, we propose the following conceptual model (Figure 1), in which we presume that social media news use would be positively associated with beliefs in both general conspiracy theories and COVID-19-related conspiracy theories (e.g. Allington et al., 2020). Based on prior research (e.g. Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2018), we hypothesize that social media news trust would moderate the positive association between social media news use and both types of conspiracy beliefs. Furthermore, with the help of previous studies (e.g. Craft et al., 2017), we inquire about whether misinformation identification would moderate the moderated relationship.

Methods

Participants

Upon approval of the institutional review board (IRB), data were collected with an online survey conducted through Amazon Mturk. A total of 760 participants aged 18 and above completed the survey (M = 38.40). Slightly over half were male participants (58.3%). Slightly over half (53.7%) of the participants leaned toward Democrat. In terms of social media use, the majority (63.1%) used Facebook once a day, if not more frequently; 47.3% used Twitter on a daily basis, if not more frequently.

Measure – Social Media News Use

Adapted from previous studies (e.g. Ardèvol-Abreu and Gil de Zúñiga, 2017), social media news use was measured using a four-item Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (6) (M = 2.46, SD = 1.60, α = .80). Sample items included, “I get most of my news and information through social media sites.”

Measure – Social Media News Trust

Adapted from previous studies (e.g. Ardèvol-Abreu and Gil de Zúñiga, 2017; Kalogeropoulos et al., 2019), social media news trust was measured using a single item, “I trust news I find on social media sites.” Responses were averaged on a Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (6) (M = 2.44, SD = 1.67).

Measure – Misinformation Identification

Adapted from previous studies (e.g. Egelhofer and Lecheler, 2019), misinformation identification was measured using a five-item Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (6) (M = 4.06, SD = 1.21, α = .88). Sample items included, “I often see stories containing deliberatively misleading elements making the reader believe it is correct.”

Measure – COVID-19-Related Conspiracy Beliefs

We presented participants with a list of six statements regarding COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs. Answers were coded on a Likert-type scale “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (6) and were added together to form a single scale with higher scores denoting higher conspiracy beliefs (M = 11.03, SD = 8.90). Sample items included, “The COVID-2019 is a weapon of the biological warfare used by foreign countries.”

Measure – General Conspiracy Beliefs

Adapted from previous studies (e.g. Cassino, 2016; Douglas et al., 2019; Douglas and Sutton, 2008), we presented participants with a list of five statements regarding general conspiracy beliefs. Answers were coded on a Likert-type scale “strongly disagree” (0) to “strongly agree” (6) and were added together to form a single scale with higher scores denoting higher conspiracy beliefs (M = 8.92, SD = 8.02). Sample items included, “Princess Diana died of deliberate murder by British intelligence agency.”

Measure – Covariates

This study controlled for gender, age, and party affiliation (Borah et al., 2013). Party affiliation was measured by asking participants to describe their party affiliation. Answers were recorded using a Liker-type scale from “strongly republican” (0) to “strongly democrat” (6) (M = 3.51, SD = 1.97).

A complete list of measurement items is listed in the Supplemental material.

Analytical Approach

To analyze the hypothesized relationships and research questions (Figure 1), standard multiple regression, PROCESS Macro model 1 for SPSS Statistics 22.0, and Process Macro model 3 for SPSS Statistics 22.0 were employed. Specifically, H1 was examined using standard multiple regression; H2 and RQ1 were investigated using PROCESS Macro Models 1 and 3. Zero-order Pearson correlations are listed in Table 1 (see Supplemental material).

Results

Our first hypothesis posited that greater social media news use was associated with greater conspiracy beliefs. As shown in Table 2 (Supplemental material), results suggested that individuals who get most news from social media sites not only had greater general conspiracy beliefs (b = 1.73, SE = 0.22, p < .001) but also more conspiracy beliefs related to COVID-19 (b = 1.76, SE = 0.25, p < .001). Thus, H1 was supported.

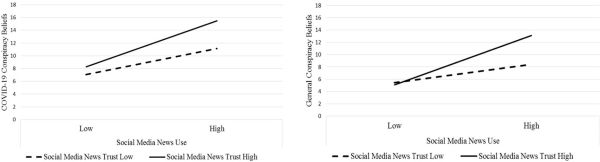

H2 hypothesized that social media news trust would moderate the relationship between social media news use and conspiracy beliefs. As shown in Figure 2, two significant two-way interactions emerged from the results, lending support to H2 (bCOVID = 0.29, SECOVID = 0.10, p = .004; bgeneral = 0.47, SEgeneral = 0.09, p < .001). Specifically, among frequent social media news consumers, greater trust toward the news was associated with higher general conspiracy beliefs and conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19. The influence of trust became negligent among users who did not consume as much social media news.

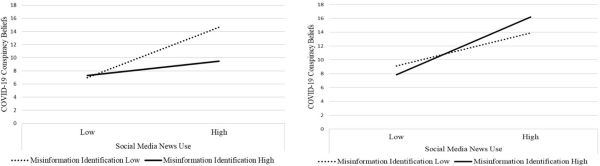

The first question further inquired about whether the moderation was moderated by misinformation identification. Two significant three-way interactions emerged from the results (bCOVID = 0.34, SECOVID = 0.08, pCOVID < .001; bgeneral = 0.29, SEgeneral = 0.07, pgeneral < .001). As can be seen from Figure 3, when social media news trust was low, among people with heavy reliance on social media news, lower misinformation identification led to higher COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. When social media news trust was high, among people with heavy reliance on social media news, higher misinformation identification led to higher COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs.

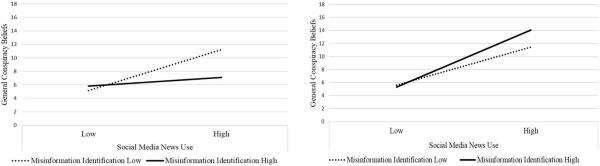

As depicted in Figure 4, when trust is low, among people with heavy reliance on social media news, lower misinformation identification led to higher general conspiracy beliefs. When trust is high, among people with heavy reliance on social media news, higher misinformation identification led to higher general conspiracy beliefs.

Discussion

This study improves our understanding of the interplay among social media news consumption, misinformation identification, and social media news trust on conspiracy beliefs. The results are illuminating but somewhat dispiriting. First of all, consistent with prior research (Allington et al., 2020; Garrett, 2019), our study revealed that social media news use was associated with more beliefs in long-standing conspiracy theories as well as recent conspiracy theories regarding COVID-19. This positive association may be due to the prevalence of misinformation disguised as authoritative news information on social media. Indeed, previous national data revealed deep-rooted concerns from the public about one-sided and inaccurate social media news (e.g. Shearer and Grieco, 2019). Conspiracy beliefs are known to reduce positive social and health attitude and behaviors (e.g. Goertzel, 2010; Jolley and Douglas, 2014a; Lewandowsky et al., 2015). Once conspiracy beliefs are formed, any attempts to correct and debunk them also seem to be futile (Stojanov, 2015; Wood, 2016). Thus, the positive relationship between social media news use and conspiracy beliefs is quite alarming especially in the current time when countries across the world are seeking effective measures to tackle COVID-19 and its associated consequences.

With social media news use contributing to conspiracy beliefs, individuals who rely heavily on social media for news information may be less compliant with government guidelines and rules such as social distancing and masking. Therefore, we call for cooperation between health agencies and social media companies to strengthen information regulations on social media sites. Moreover, existing evidence showed that health professionals can stop the spread of misinformation by refuting misleading information (Chou et al., 2018; O’Connor, 2020). Many authoritative health organizations such as World Health Organization have already taken the effort to combat misinformation using social media (i.e. WhatsApp). We exhort health professionals to continue rebutting and refuting misinformation and disinformation on social media to deter or delay the formation of conspiracy beliefs among social media news consumers.

Second, in line with prior research (e.g. Anspach and Carlson, 2020; Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2018; Turcotte et al., 2015), trust toward social media news was found to be a significant moderator of the relationship between social media news use and conspiracy beliefs. Worryingly, individuals with heavy reliance on social media news and greater news trust had the highest level of general conspiracy beliefs and COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs. Previous studies have repeatedly indicated that “people tend to seek accurate information from sources they consider reliable and to avoid the exposure to sources they distrust” (Ardèvol-Abreu et al., 2018: 706). Our findings further demonstrated that frequent exposure of and higher trust toward social media news may result in negative consequences that scholars and health professionals should be wary of. For example, data showed that young adults consume social media news frequently with fewer concerns about fake information (Mitchell et al., 2019; Rideout and Fox, 2018). As the COVID-19 infection rate has increased intensely among the younger generation in the USA (Downey, 2020), the pandemic maybe even worsened by young people who believe in conspiracies and refuse to adhere to health guidelines issued by the government.

To alleviate the situation, many scholars indicated that media literacy interventions may be beneficial to reduce conspiracy beliefs for heavy social media news seekers and believers (Craft et al., 2017; Vraga et al., 2020). Specifically, improving the critical consumption of news by enhancing the ability to identify false information is particularly helpful. Thus, as our last inquiry, we investigated the role of misinformation identification in the moderated relationship. Findings suggested that the ability to identify misinformation is only protective for social media news users with lower trust toward the platforms. For social media news consumers who blindly trust social media news, even if they can identify false information, they are still more likely to fall prey to conspiracy theories. Two factors may explain such counterintuitive results. First, media literacy contains many components such as digital literacy, information literacy, and news literacy and thus misinformation identification only constitutes a minuscule portion of media literacy in the context of social media. Therefore, for individuals with ingrained trust toward social media, it is crucial to have systematic learning of social media literacy. Thus, providing a comprehensive media literacy intervention by educating them about the social media environment (i.e. no gatekeepers) and social media news production and dissemination (i.e. social computing, algorithms) may be helpful. Second, a political factor may also be responsible. The current president Donald Trump has repeatedly berated authoritative news agencies such as Cable News Network (CNN), National Broadcasting Company (NBC), and Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) as “fake news” generators (e.g. Slack, 2017). The president himself also repeatedly spread misinformation and disinformation under multiple occasions such as calling the COVID-19 virus the “China virus” (Brito, 2020). Thus, supporters of Donald Trump and the Republican Party may perceive the truthful news, especially the kind associated with CNN or NBC on social media, as less trustworthy and tend to believe in fabricated information that is aligned with the worldview of Donald Trump and the Republican Party.

However, there is a silver lining. That is, among social media news seekers who do not blindly trust social media, misinformation identification did significantly reduce their beliefs in general conspiracy theories and those related to COVID-19. As prior research demonstrated, critical thinking and skepticism are protective shields that assist individuals to navigate through the complex digital environment (e.g. Vraga and Tully, 2019). Thus, improving critical thinking skills and capabilities, developing vigilance about false information, and being open-minded by seeing both sides of a story are important lessons for individuals prior to social media news exposure and also lifelong learning for each and every social media consumer.

This study is not without limitations. First, data were collected using Amazon mTurk, an online survey portal with a national pool of participants. The evaluation of collecting survey data via mTurk has been mixed and inclusive (e.g. Berinsky et al., 2012; Paolacci and Chandler, 2014). However, prior research did suggest that a large portion of its participant pool consists of individuals interested in news, who are exactly the population of interest in this study (Huff and Tingley, 2015). That being said, we recommend future studies to replicate our model by sampling a national pool of participants using other online channels or face-to-face venues, which will increase the generalizability of the results. Second, social media news trust was measured using a single item. Although this decision followed prior research (e.g. Kalogeropoulos et al., 2019), future studies could measure social media news trust using multiple items.

Third, this study was not built upon a particular theory, rather, it tested a model that contains theoretical constructs with hypothesized or confirmed associations. Thus, we recommend much caution when interpreting the findings since there might be other factors that may interfere with the strength and direction of the results. For example, social media news trust may be swayed by variables, including individuals’ educational background (e.g. Dutton and Shepherd, 2006), trust in science (e.g. Huber et al., 2019), and political affiliation (e.g. Lee, 2010), that are not included in the model. These factors are important due to the fact that trust in social media precisely pertains to individuals’ potential vulnerability to information provided from less-than credible sources and that COVID-19 has been politicized in the United States, hence, their educational levels, science literacy, and partisanships could play a role. We thereby encourage scholars to not only replicate our study but further include other theoretically relevant factors (i.e. the aforementioned) as the independent variables, to examine their associations with social media news use and news trust. Moreover, future research should use experimental data to test theoretically driven paths and examine the psychological mechanisms involved in the model. Finally, these results are from a cross-sectional survey, hence all relationships examined and supported are correlational, and not causal. However, we are confident about the associations because our conceptual model is supported by prior literature. Moreover, we tested the relationships using two dependent variables, and our findings held in the case of both general conspiracy beliefs and COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs.

Despite these limitations, this study provides further insight into the interplay among social media news use, news trust, and misinformation identification on conspiracy beliefs. Considering 70% of Americans use at least one social media site and the majority of these social media users consider social media the main news venues (Shearer and Matsa, 2018), our research is crucial. Clearly, exposure to social media news and having a blind trust toward social media news content could be risky due to the unregulated flow of information on social media. However, developing the mindset and skills to critically analyze and assess information would to a certain extent protect individuals from falling prey to misinformation.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Public Understanding of Science 30:8 (03.05.2021, 977-992) under the terms of a Creative Commons license.