Misinformation is part and parcel of the current wave of radical right populism.

By Dr. K.P. (Petter) Törnberg

Assistant Professor in Computational Social Science

University of Amsterdam

By Dr. Juliana Chueri Barbosa Correa

Assistant Professor of Political Science and Public Administration

Assistant Professor of Multi-layered governance in Europe and beyond (MLG)

University of Lausanne

Abstract

The spread of misinformation has emerged as a global concern. Academic attention has recently shifted to emphasize the role of political elites as drivers of misinformation. Yet, little is known of the relationship between party politics and the spread of misinformation—in part due to a dearth of cross-national empirical data needed for comparative study. This article examines which parties are more likely to spread misinformation, by drawing on a comprehensive database of 32M tweets from parliamentarians in 26 countries, spanning 6 years and several election periods. The dataset is combined with external databases such as Parlgov and V-Dem, linking the spread of misinformation to detailed information about political parties and cabinets, thus enabling a comparative politics approach to misinformation. Using multilevel analysis with random country intercepts, we find that radical-right populism is the strongest determinant for the propensity to spread misinformation. Populism, left-wing populism, and right-wing politics are not linked to the spread of misinformation. These results suggest that political misinformation should be understood as part and parcel of the current wave of radical right populism, and its opposition to liberal democratic institution.

Introduction

Misinformation on social media has become a major concern for both the public and academics alike (Del Vicario et al., 2016). Research has examined how unreliable news articles can achieve viral spread on social networks (Vosoughi et al., 2018), warning for an online information climate increasingly characterized by biased narratives, disinformation, and conspiracy theories (Törnberg, 2018). However, while this type of media-driven misinformation became a focus of key interest in the wake of the 2016 election, a growing body of evidence now suggests that online misinformation may not be as widespread as previously thought (e.g., Allen et al., 2020; Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2019). Academic attention has hence recently shifted toward a different driver of false beliefs in the electorate: misinformation campaigns orchestrated by political elites (Mosleh and Rand, 2022).

While studies show that most individuals do not spread or hold false beliefs (Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2019), misinformation remains widespread among particular electoral groups. In the United States, for instance, 70 percent of Republicans believe that Biden’s 2020 win was illegitimate, a belief fueled by claims of widespread fraud promoted by Republican politicians (SSRS, 2023). Such false beliefs have profound implications for democratic processes, as they undermine voters’ ability to make decision and is associated with distrust in democratic institutions (Zimmermann and Kohring, 2020). Rather than focusing on misinformation as an expression of general decline in access to reliable information, scholars have thus suggested that misinformation is “introduced into the political communication space through political elites” (Jungherr and Schroeder, 2021: 3). In an influential article, Bennett and Livingston (2018) diagnose an “disinformation order,” arguing that the rise of misinformation is associated to the rise of a particular type of politics.

Precisely what type of politics drives misinformation, however, has been subject to debate. A dominant viewpoint is that misinformation is linked to populism (Hameleers, 2020), defined by antielitist rhetoric that tends to cast mainstream media as part of a corrupt elite (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007; Krämer, 2017). Several case studies have shown that populist parties engage in successful misinformation campaigns (e.g., Bergmann, 2018; Gaber and Fisher, 2022; Recuero et al., 2021). The “post-truth era” (McIntyre, 2018) has been argued to be part and parcel of the “populist moment” (Mouffe, 2019), as populist politicians draw strategically on social media to communicate directly with the public and disseminate “alternative truths.” Bennett and Livingston (2018), however, criticize communication research for “settling on populism as an easy catch-all reference,” questioning whether mere antielitism can fully explain the motivation of political parties to spread misinformation (p. 131). They argue instead that misinformation may be more closely linked to exclusionary ideologies and hostile relations to democratic institutions, which are characteristic of (populist) radical right political actors. Research has found that radical right populist parties tend to gain electoral advantages from a misinformed electorate—often at the expense of mainstream parties—implying that such parties may have incentives to mislead their electorate (Van Kessel et al., 2021; Zimmermann and Kohring, 2020).

There are however few empirical studies that speak to the question of the relationship between party politics and misinformation. This is in part for methodological reasons: as empirical research on online misinformation tends to draw on large datasets from anonymous posters, there is limited comparative data on dissemination of misinformation by political elites. As a result, there exists as of yet no cross-national comparative studies on dissemination of misinformation by political elites (Lasser et al., 2022 represents an exception, examining misinformation across three countries). This begs the questions: Which parties are more likely to spread online misinformation? Is misinformation linked to populist parties, or is it specifically an expression of the populist radical right?

To answer these questions, this article studies misinformation as an expression of party politics by drawing on a comprehensive database of 32M tweets from parliamentarians in 26 countries, over 6 years, and several election periods (van Vliet et al., 2020). The dataset is combined with the Parlgov, and V-Dem databases, giving detailed information about the parties, and cabinets. To identify cases of misinformation, we examine the URLs that the politicians share, and use the Media Bias/Fact Check (MBFC) database and the Wikipedia Fake News list to identify politicians sharing misinformation in tweets. We employ multilevel regression models to identify the attributes of parties that are associated to the likelihood of disseminating false or misleading information.

While the literature on low-factuality information commonly differentiates between “misinformation” and “disinformation”—the former implying that the disseminator is unaware that the information is false or inaccurate, while the latter describes spreading false information with intent (Freelon and Wells, 2020)—we here use “misinformation” in the broad sense. In the context of misinformation spread by political parties, it is ultimately both impossible and irrelevant to know whether specific politicians deep down believe in the messages that they share (Hameleers, 2023; Hameleers et al., 2022).

We find that parties in Western countries do spread misinformation on Twitter, and that certain political ideologies are linked to higher likelihood of spreading misinformation. Populism in itself is not associated to misinformation, right-wing parties are not more likely to spread misinformation, and that left-wing populists are not more likely to spread misinformation than mainstream parties. However, politicians associated with (radical) right-wing populist parties do spread more online misinformation than their mainstream counterparts—suggesting that the connection between populism and misinformation relates specifically to this form of politics.

Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the relationship between party politics and misinformation, bringing a new approach and new data to a long-standing debate. The results suggest that the rise of political misinformation is associated to the recent wave of radical-right populism—both emerging as part of a breakdown of trust in press and politics. These political movements are exploiting declining confidence in official information by creating alternative information sources with the aim of undermining institutional legitimacy and destabilize mainstream parties, governments, and elections. As misinformation is shaped by the political logic of radical right populism, so the politics of the radical right is shaped by the incentives of an attention-driven media environment, which offers agenda-setting and control over public attention. Misinformation and radical right populism should be understood as inextricably linked and synergistic, representing two facets of the same political phenomenon.

More broadly, our study suggests that future research should approach misinformation as a political phenomenon. It should be examined as an aspect of party politics, serving as a strategy designed to mobilize voters against mainstream parties and democratic institutions. To support such a research approach, the database underlying the study will be made publicly available, facilitating further comparative empirical research on the relationship between party politics and misinformation.

Social Media and the Rise of Misinformation

Anxiety over online misinformation is mounting. A wave of research in the post-2016 period described social networks as offering fertile soil for the spread of misinformation, resulting in an online information ecosystem increasingly dominated by biased narratives, disinformation, and conspiracy theories, with (Del Vicario et al., 2016). Social media’s democratization of content creation and sharing meant that unverified and biased information could spread like “wild-fire over social networks through direct connections between news producers and consumers” (Törnberg, 2018: 1). Reports warned that misinformation was becoming so pervasive as to be a major threat to human society (Howell, 2013). Partly due to such dire warnings, Americans are today more concerned about misinformation than terrorism, sexism, racism, or climate change (Mitchell et al., 2019). The concern about misinformation also triggered a surge in academic interest, especially following the 2016 US presidential election, leading to the publication of more than 2,000 research papers (Allen et al., 2020; Mosleh and Rand, 2022).

However, a growing scholarship has questioned the dominant understanding of misinformation as a pervasive social media phenomenon. Studies show that misinformation represents only a small fraction of people’s information diet (Allen et al., 2020; Altay et al., 2023; Cordonier and Brest, 2021), and that most people do not share unreliable news (Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2019). A growing body of research argues that alarmist narratives about misinformation should be understood as a “moral panic” (Carlson, 2020), which can itself have negative consequences (Jungherr and Rauchfleisch, 2024). While misinformation can play a significant and problematic role in politics, social media may not be the chief culprit (Tsfati et al., 2020): studies show that television is by far the dominant media source, in particular for news (Allen et al., 2020; Broockman and Kalla, 2022). Even when individuals do come across misinformation on social media, they may not be as gullible as previously believed: while trust in the media is low, trust in social media is even lower, and people have been found to deploy a variety of strategies to detect and counter misinformation (Wagner and Boczkowski, 2019).

Rather than a pervasive phenomenon expressive of a general decline of access to reliable information, misinformation increasingly appears as a phenomenon chiefly associated to particular electoral groups (Broniatowski et al., 2023; Motta et al., 2023). While most people do not engage with unreliable sources (Cordonier and Brest, 2021), a small minority accounts for most of the misinformation consumed (Grinberg et al., 2019). What characterizes this group is not that they lack access to high-quality information, but certain traits that make them more likely to seek out misinformation (Broniatowski et al., 2023; Motta et al., 2023), such as low trust in institutions or strong partisan identity (Osmundsen et al., 2021), and strong partisanship and political identities (Altay et al., 2023). Misinformation in the electorate moreover tends to be focused around particular controversial and polarized issues, rather than a being a general phenomenon (Nyhan, 2020).

As a result of such findings, a growing scholarship argues that misinformation instead should be understood as driven by coordinated campaigns of political elites (Mosleh and Rand, 2022), and as an expression of a particular type of politics (Bennett and Livingston, 2018). Scholars have suggested that research attention should move from “evocative but empirically marginal phenomena toward the structural transformations that give rise to these fears, namely those that have impacted information flows and attention allocation in the public arena” (Jungherr and Schroeder, 2021: 1). While individuals may not generally trust what they see on social media, they are more likely to believe their partisan leaders—even when their messages seem to contradict factual information (Bisbee and Lee, 2022).

Politicians can moreover leverage their roles to reach an audience both on social media and through legacy media. Television—the chief source of news and political information—often functions as a gateway to misinformation from political elites (Benkler et al., 2018; Tsfati et al., 2020). While political misinformation may start on social media, it often passes through legacy media, resulting in an “amplifier effect” for stories that would be dismissed in earlier eras of more effective press gatekeeping (Bail, 2012; Broockman and Kalla, 2022). Trump’s tweets, for instance, were not so much read on social media as they were consumed through television (Wardle, 2021).

However, even when focusing on political elites as the drivers of misinformation, social media still plays a crucial role. Social media are part of the larger structural changes in our information environment that has made it more feasible for political elites to control the media agenda (Jungherr and Schroeder, 2021): a changing political economy of attention (Jungherr et al., 2020) and financial strains on traditional media organizations (Nielsen, 2016). Online advertising and platformization have brought the rise of a media ecosystem characterized by fierce competition for attention, largely unrestrained by editorial control and journalistic standards (Bessi et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2021). The effect is a privileging of sensationalist, provocative, and often misleading content is likely to garner more clicks and engagement compared to traditional, fact-based reporting—what Munger (2020) refers to as a “clickbait media” model. Political parties can exploit this attention-driven media environment to achieve their interests and impose their agenda—and misinformation can be an effective part of such a strategy.

Misinformation and Populism

For unscrupulous political parties, spreading misinformation can serve several purposes. It can enable them to control public attention, for instance to distract voters and media from scrutinizing their actions or policies. Misinformation can help shape public opinion, by affecting how voters perceive certain issues, policies, or even political opponents (Bennett and Livingston, 2018). It can be a powerful tool to energize and mobilize a politician’s core supporters by reinforcing existing beliefs, fears or resentments, or spreading false information that cast political opponents in a negative light, politicians can strengthen the loyalty, energy and activism of their base (Tucker et al., 2018).

Understanding misinformation as driven by campaigns from political elites raises the question of whether it is an expression of particular forms of politics. Some scholars have suggested that misinformation may be linked to populist parties. Populism is generally understood as an ideology or a communication style that divides society into two antagonist groups: the “pure people” and the “corrupt elite,” and argues that politics should be done according to the will of the former (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007; Mudde, 2004). The antielitist appeals of populists tend to come with attacks against mainstream institutions such as the media (Hameleers, 2020; Waisbord, 2018), which are seen as part of the “corrupt elite” and as favoring mainstream political parties (Jagers and Walgrave, 2007; Krämer, 2017).

Populist communication is hence often associated with a strong rhetoric against media, which are accused of lying, or promoting the elite’s worldview (Hameleers, 2020). Populism is hence seen as almost definitionally linked to a rejection of mainstream media, and by extension to its dominant notions of veracity. Just like misinformation, populism is hence associated with a falling trust in mainstream institutions and the “elite” (Bennett and Livingstone, 2018). Empirical case studies have reported that several successful misinformation campaigns were led by populist political leaders, such as the election of Trump in 2016 (Bergmann, 2018), and Bolsonaro in 2018 (Recuero et al., 2021), and during the Brexit campaign (Gaber and Fisher, 2022).

Populist parties furthermore tend to have different relationship to the press than mainstream parties, using social media as a strategic means to communicate directly with the public, thus bypassing “gatekeepers” of legacy media, and disseminating content from “alternative sources.” The relationship between radical right populists and media is moreover marked by a savvy manipulation of media logic: populist leaders often engage in provocative and sensationalist rhetoric, understanding that such content is more likely to be picked up and amplified by both traditional and new media platforms, thus gaining broader visibility (Engesser et al., 2017).

However, it is less established what the role of the host ideology is in the connection between populism and misinformation. Bennett and Livingston (2018) argue against the notion that misinformation is linked to populism in the broad sense, and instead links it to exclusionary ideologies and the hostility to democratic institutions characteristic of radical right populist actors. The only existing empirical study focusing on a multiparty context however suggest that populists from both the left and right sides of the political spectrum are more likely than mainstream parties to share low factual information, but identifies a stronger association with right-wing than left-wing populists (Lasser et al., 2022). This mismatch is also present among voters: populist radical right voters are more likely to be misinformed, while also believing that they are more politically informed than populist left-wing voters (Van Kessel et al., 2021; Zimmermann and Kohring, 2020). The researchers suggest that the causal mechanism underlying this association is that the populists’ Manichean understanding of politics attracts voters who are particularly disenchanted with democracy and distrustful of mainstream institutions, especially mainstream media (Zimmermann and Kohring, 2020). This inclination makes them more receptive to false information derogating their “enemies” (Castanho Silva et al., 2017) and conspiracy theories (Bergmann, 2018), which may provide incentives for their political elites to draw on misleading information.

There are also some theoretical reasons to believe that right-wing populists are particularly likely to share misinformation: right-wing populists often capitalize on cultural and social fears, which can be effectively exacerbated by misinformation (Waisbord, 2018). This includes leveraging anxieties about national identity, cultural changes, or security threats—themes that can be easily sensationalized. Left-wing populism, on the other hand, focuses more on economic grievances, viewing economic elites and economic institutions as the main culprits of the economic insecurity of “the people” (March, 2017; Schroeder, 2019). As a result, left-wing populist parties blame economic elites and institutions for inequalities and economic deprivation, largely sparing mainstream media from attacks (March, 2017; Schroeder, 2019). Misinformation campaigns are hence more suitable for communication strategies of right-wing populist parties’ emphasis on the cultural role of mainstream media, than for left-wing populists’ focus on economic inequalities.

In light of these competing views on the politics of misinformation, we develop three hypotheses on the relationship between political party ideologies and the dissemination of misinformation:

H1: Parties with higher populist ideology are more likely to spread misinformation on Twitter.

H2: Parties with higher scores on the left-right ideological scale are more likely to spread misinformation on Twitter.

H3: Populist parties on the right side of the political spectrum are more likely to spread misinformation on Twitter than left-wing populist parties.

Methods and Data

We draw on a comprehensive database of 32M tweets from 8,198 parliamentarians in 26 countries, over the 2017 to 2022 period, and several election periods (van Vliet et al., 2020). The period thus includes the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results should thus be understood as in part pertaining to the misinformation spread during this period. The dataset includes all parliamentarians that had Twitter accounts, and all the messages that they sent during this period, collected using Twitter’s streaming API. According to van Vliet et al. (2020), the countries included are all member states and candidate member states of the European Free Trade Association where at least 45 percent of parliamentarians are on Twitter: Austria, Belgium, France, Denmark, Spain, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Malta, Poland, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden, New Zealand, Turkey, United States, Canada, Australia, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Latvia and Slovenia (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Information File). (It should be noted that it is not possible to further extend the dataset as Twitter—now X—no longer offers data access.)

The dataset thus provides an important lens into the online communication of political parties in many Western countries and offers several important advantages. First, as the database was created by following specific users, it covers all messages sent by the politicians, rather than a sample or subset. Second, while parliamentarians are far from the only political agents that are likely to spread misinformation, the dataset has the advantage of offering a clearly defined and delineable group. Third, the data can be combined with existing comparative databases with information about parties and countries. To enable a comparative examination of the factors that shape the spread of misinformation, the shared version of the dataset was combined with the Parlgov, Manifesto Project, CHES, Electoral Systems, and V-Dem databases, giving detailed information about the parties, countries, and electoral systems. In this study, we draw on data from Parlgov and V-Dem.

We identify 18,026,150 URLs shared by the politicians in these tweets. Since URLs that are shared on Twitter/X are automatically shortened (i.e., replaced by “t.co” followed by an identifier string), we first expanded each URL. We developed custom-written scripts to do so and created a database of all shared links. (As this database has significant use for additional research, we will share the full database of shared URLs.) From these URLs, a large fraction—14,695,110—go to Twitter itself. Many other go to other social media platforms, such as Facebook (152,349) or YouTube (138,724). Excluding these, 2,939,372 URLs remain.

To identify cases of misinformation, we scraped the MBFC and the Wikipedia Fake News list to create a database of 646,058 URLs with an associated factuality classification. MBFC offers the largest dataset covering biased and low factual news sources, and has been widely used to identify misinformation shared on social media (e.g., Baly et al., 2018; Gallotti et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). MBFC describes each media outlet with a level factuality (“very low,” “low,” “medium,” “high,” “very high”), which represents the likelihood that articles from the source contain misleading information or misinformation. The Wikipedia Fake News list focuses specifically on news sources with very low factuality. Combining the database of misinformation links and the shared URLs, we produce a database of the level of factuality of the sources shared by the politicians, which covers 582,148 shared URLs. Using these, we create an indicator to measure the factuality of a politician or party based on the links they have shared. We create this variable by assigning values to each level of factuality (“very low”: 0, “low”: 0.25, “medium”: 0.5, “high”: 0.75, “very high”: 1.0) and calculating the mean value of the party. As we aggregate on the party level, the result is an indicator that captures the factuality of the links shared by a specific party. We refer to this indicator as their factuality score. It should be noted that the factuality score captures not only misinformation that is shared with the direct purpose of misleading but also sharing that is motivated by, for instance, the presence of a relationships between parties and media organizations with a culture of misinformation.

To ensure the robustness of our methods, the factuality measure was manually validated to ensure that the articles shared in fact contain misinformation (see Supplemental Information File). We selected a stratified random sample of 50 articles from each of the five predefined factuality levels, totaling 250 articles. These were manually analyzed, ensuring that the coder was unaware of the outlet’s assigned factuality labels to avoid potential bias, and categorized for their level of factuality. The results are reported in Supplemental Tables S6 and S7, and show that articles from high-factuality outlets tend to contain high-quality factual information, and that a majority of the articles shared by politicians associated to low-factuality outlets consists of misleading information or misinformation.

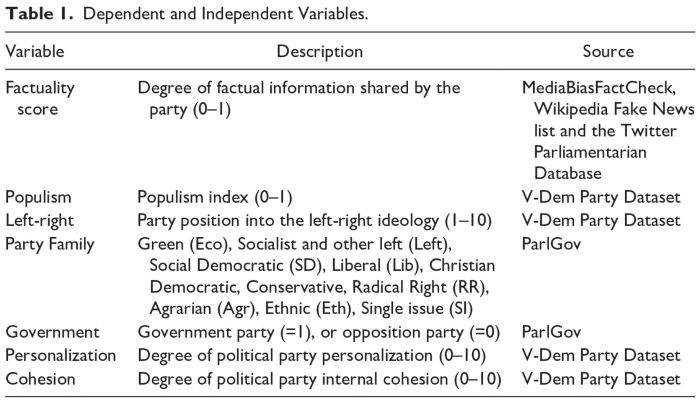

Parties’ populist ideology and left-right ideological position are obtained from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Party Dataset (Lührmann et al., 2020), and party family is obtained from the ParlGov dataset (Döring and Manow, 2020). Their populism index measures the extent to which parties use populist rhetoric, combining people-centrism and antielitism measurements. Left-right placement captures parties’ ideological stances on economic issues. The parties’ government participation is drawn from the ParlGov dataset (Döring and Manow, 2020). We also include control variables to access the party degree of cohesion and personalization provided by the Varieties of Democracy Party Dataset (Lührmann et al., 2022). At the party level, we control for the degree of personalization and internal party cohesion. If political parties rely heavily on one politician and serve their priorities, party aggregated results do not fully characterize the importance of the party in misinformation campaigning. Similarly, if parties lack internal cohesion and elites fundamentally disagree on parties’ strategies, the aggregated factual score might not entirely reflect the dissemination of low factuality information by a segment of the party. Table 1 summarizes dependent and independent variables of the study.

Focusing on parties that have shared at least 100 URLs, our aggregated database comprises 177 parties over 26 countries. Given the nested structure of our data, we employ multilevel analysis, with random country intercepts. This strategy allows us to control for country heterogeneities while assessing how political party characteristics influence the results. As our dependent variable is an indicator showing the average factuality of the information shared by the party, varying between zero and one (see variable distribution in the Figure S1 in the Supplemental Information File), we employ generalized linear mixed-effects model for beta-distributed response variable. For descriptive statistics of variables, and the factuality scores across countries and party families, see Tables S2–S4 in the Supplemental Information File.

Results

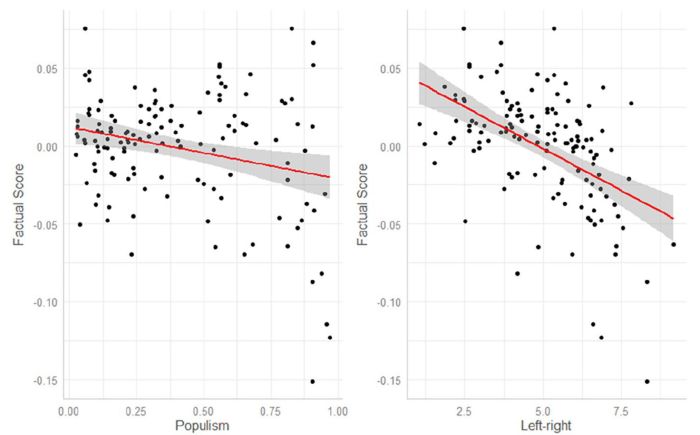

In order to assess the relationship between our dependent and independent variables, Figure 1 shows the associations between the parties’ factuality scores centered by country mean and economic ideology (right side) and populist ideology (left side). We use this adjusted measure to control for possible country differences in media structures and elite communication. Figure S2 in the Supplementary Information File presents the plot with the unadjusted factuality scores. Both relationships are negative, suggesting that higher levels of populism and right-wing ideologies are associated with lower factuality scores. However, Figure 1 shows a weak relationship between populism and factual scores, with great variability in factuality scores for parties that exhibit high levels of populism, suggesting heterogeneous effects among those parties.

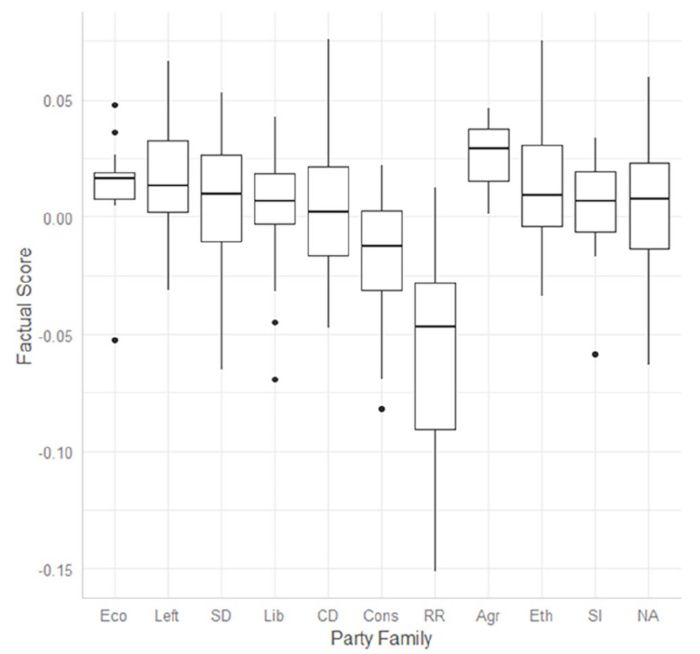

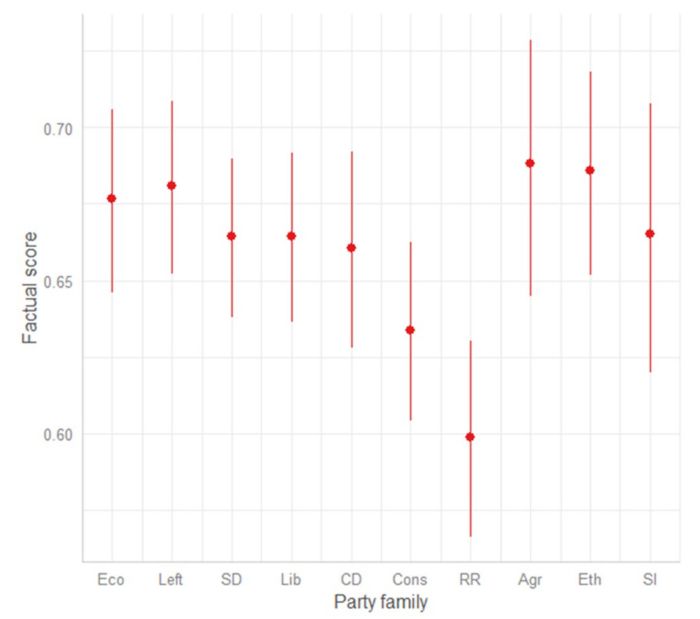

To further investigate the relationship between party ideology and misinformation, Figure 2 shows the box-plot levels of factual scores for different party families (see Figure S3 in the Supplemental Information File for the unadjusted party factual scores). Although populism is not explicitly considered among these ideologies, the figure reveals that conservative and radical-right parties—which often also include populist ideology (see Figure S6 in the Supplemental Information File)—present the lowest levels of factuality scores. Parties on the left side of the political spectrum, as well as Christian Democrat and Liberal parties, present similar median factual scores. Notably, Socialist and other left-wing parties that in some cases exhibit populist ideology (see Figure S6 in the Supplemental Information File), present the highest median factual scores.\

Taken together, these descriptive statistics suggest that none of these variables provide a clear account of the ideological drivers behind misinformation campaigns. Instead, they indicate the need for an analysis that considers the interactive effects between them.

Moving to the inferential analysis, we run two generalized linear mixed-effects models for beta-distributed responses to assess the likelihood that parties share factual information. We add random country effects to account for countries heterogenous effect. (We also run similar models without the hierarchical structure and with robust standard errors. The results are available in Figures S4 and S5 in the Supplemental Information File and are in line with the ones presented here).

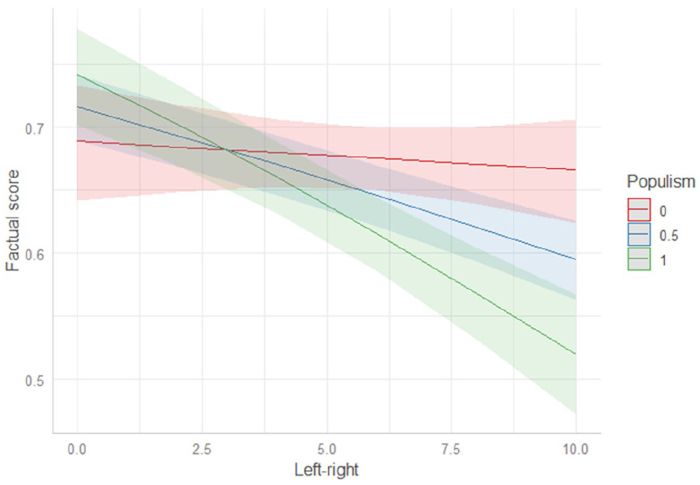

In the first model, we include an interaction effect between populist and left-right ideologies and controls for party internal cohesion, party participation in the government, and degree of party personalization. Regression output, available in Table S5 in the Supplementary Information File, reveals that the effects of populist and left/right ideologies are not significant, whereas the interactive term shows a significant effect with 95% of statistical confidence.

Figure 3 illustrates how this interaction affects the dependent variable by showing the predicted probability of the factuality score across the left–right ideology at three different levels of populism: 0, 0.5, and 1. It shows that for nonpopulist parties, economic ideology does not affect the likelihood of a political party to share low-factuality sources. However, for both medium and high populist scores, economic ideology matters, as right-wing parties are significantly more likely to share misinformation that left-wing parties. A comparison between nonpopulist (populism index = 0) parties and populist parties (populism index = 1) indicates that right-wing populist parties, scoring around 6 or more on the left-right scale, are significantly more likely than right-wing nonpopulist parties to share misinformation.

In the second model,1 we analyze the effect of party family on the factual scores of parties’ communication, controlling for party internal cohesion, party participation in the government, and degree of party personalization. Full regression results are available in Table S5 in the Supplemental Information File. Figure 4 presents the predicted factual score by party family, with other control variables kept at their mean values. The results confirm that radical-right parties have the highest likelihood of sharing low factual information compared to other party families. This difference is significant with 95% confidence from all party families except for Conservative and Single-issue parties. The relatively high level for Conservative parties may reflect that the boundary between Conservative and Radical Right parties have blurred in recent years (Krause et al., 2023).

These results show that neither the ideological position nor the populist ideology alone explains the politicians’ propensity to spread misinformation. Instead, a combination of populism and right-wing ideology is associated with parties sharing lower factuality information. This result leads us to accept hypothesis 3, and reject hypotheses 1 and 2.

Moreover, the comparison between party families indicates that misinformation is likely associated with the radical component of the populist radical-right ideology.

Discussion and Conclusion

By studying the relationship between misinformation and party politics, this article has sought to examine misinformation as a political phenomenon, in which certain political agents use misinformation to exploit a low-trust environment and media environment to draw political benefits. We have analyzed the spread of misinformation by political parties on Twitter, by combining a unique dataset of 32 million tweets from parliamentary accounts in 26 countries with a list of 646,058 URLs and their associated factuality scores, along with party-level variables. This has allowed us to examine the factors influencing the probability of parties sharing low-factuality information.

Our results suggest that neither the left–right ideological position nor the populist ideology alone explain party members’ propensity to spread misinformation on Twitter. While previous scholarship has argued for a connection between populism—by definition linked to distrust of institutions such as mainstream media—and misinformation, our findings do not support such a link: only when combined with right-wing ideology is populism significantly associated with the spread of misinformation. Our comparison between party families furthermore indicates that misinformation is likely associated with the radical component of the populist radical-right ideology, which is characterized by hostility toward democratic institutions. In short, when it comes to misinformation, the main problem is not populism but radical-right populism.

The current waves of misinformation and radical right populism both have their roots in a legitimacy crisis of democratic institutions (Mair, 2023), which many scholars argue emerged in response to the hollowing out of conventional political organizations in Western democracies and a period characterized by neoliberal consensus, rising levels of inequality, and growing power of business elites (Crouch, 2019). The resulting breakdown of trust opened the gates both for a political challenge seeking to overthrow established politics, and a parallel challenge against established media structures. There are hence reasons to view misinformation and the current wave of radical right populism as inextricably intertwined: the loss of trust and legitimacy in mainstream institutions opens national information systems to vulnerability for strategic use of misinformation by political actors, and the political movement can in turn draw on misinformation to undermine institutional legitimacy and destabilize mainstream parties, media, governments, and elections.

While left-wing populists also reject “the elite,” they focus primarily on the economic elite and economic grievances (March, 2017; Schroeder, 2019). Misinformation campaigns are hence more suitable for communication strategies of right-wing populist parties’ emphasis on the cultural role of mainstream media, than for left-wing populists’ focus on economic inequalities. While the radical right seeks to overthrow democratic institutions in favor of strong authoritarian leaders, the left has tended to celebrate participatory and direct democracy.

There appears to be a symbiotic relationship between these populists and the “clickbait media” model (Munger, 2020): the attention economy promotes content that captures and retains user interest, often measured in terms of likes, shares, comments, and overall engagement (Engesser et al., 2017). Radical right populists have been effective in creating and utilizing alternative media ecosystems that amplify their viewpoints, ranging from online news websites and blogs to more traditional forms of media like television and radio, which have been reconfigured to cater to populist radical right narratives (Haller et al., 2019; Nagle, 2017). The strategic construction of an alternative media ecosystem serves multiple purposes: it amplifies their ideological messages, creates a sense of community among followers, and provides a counter-narrative to mainstream media reporting. Left-wing populists have not established a parallel media ecosystem to the same extent.

The relationship between alternative media and radical right populists goes both ways, as the right-wing media ecosystem has often been part of shaping and directing right-wing populist politics: scholars have documented how radical-right voices on talk-radio, cable television, and social media have been propelled into stardom by seizing upon previously unarticulated resentments and identities (Hemmer, 2016). These voices have often become figureheads of political movements and powerful mobilizing forces behind radical right populist parties—coming to wield significant influence over their political evolution.

In summary, this article has shown the potential of viewing misinformation as an expression of party politics, bringing new data to a long-standing debate. The results suggest that current political misinformation is not linked primarily to populism, but specifically to the populist radical right, and points to its particular relationship to an ecosystem of alternative media—largely unrestrained by journalistic integrity and standards. These radical right populist movements are exploiting declining confidence in official information and established democratic institutions, drawing on misinformation with the aim of undermining institutional legitimacy and destabilize mainstream politics. As the media ecosystem is shaped by the political logic of radical right populism, so is radical right politics shaped by the incentives of an attention-driven media environment. Misinformation and radical-right populism must hence be understood as inextricable and synergistic—two expressions of the same political moment.

Several limitations of our approach should be noted. First, since Twitter (now X) no longer allows researcher access to data, the database is no longer updated and covers only the 2017 to 2022 period; the most recent developments hence cannot be accounted for. Second, the available data include only Western democracies. Future comparative research should also seek to include the central question of the role of misinformation in non-Western and particularly authoritarian contexts (see e.g., Huang, 2017; Wang et al., 2023; Wang and Huang, 2021; Zhu and Wang, 2021). Third, URLs are not the only form in which misinformation can take place—as politicians may share misinformation also in the message text. The method used in this article furthermore looks at politicians spreading links to low-factuality sources, rather than examining the actual content of the shared articles. Future research should identify ways of identifying misinformation in textual messages and broaden the definition misinformation. Such an approach may become possible through recent advances in natural language processing. Fourth, while the misinformation database used in this article is considered among the most comprehensive, it does not contain all possible links, which is an inherent limitation of URL-based misinformation research. Finally, this article has looked specifically at misinformation on Twitter. While Twitter remains the most important social media platform for political elites, future studies may extend this to additional platforms, or focus on multiplatform comparison.

To support future research seeking to understand misinformation as a political phenomenon, the database used in this study will be made publicly available, with all URLs shared by the politicians, allowing researchers to examine additional factors and conditions that shape the likelihood of elites’ sharing misinformation. There are a range of possible directions in which future research can continue, including the relationship between misinformation and temporal dimensions, whether politicians’ share misinformation on particular political topics, and examining how other country-level contextual factors influence parties’ decisions to employ misinformation campaigns.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Due to data availability, this model does not include Latvia.

References

- Allen J., Howland B., Mobius M., Rothschild D., Watts D. J. 2020. “Evaluating the Fake News Problem at the Scale of the Information Ecosystem.” Science Advances 6(14): eaay3539. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Altay S., Berriche M., Acerbi A. 2023. “Misinformation on Misinformation: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges.” Social Media + Society 9(1):205630512211504. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Bail C. A. 2012. “The Fringe Effect: Civil Society Organizations and the Evolution of Media Discourse About Islam Since the September 11th Attacks.” American Sociological Review 77(6):855–879. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Baly R., Karadzhov G., Alexandrov D., Glass J., Nakov P. 2018. “Predicting Factuality of Reporting and Bias of News Media Sources.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 3528–3539. Association for Computational Linguistics. Crossref.

- Benkler Y., Faris R., Roberts H. 2018. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford University Press. Crossref.

- Bennett W. L., Livingston S. 2018. “The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions.” European Journal of Communication 33(2):122–139. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Bergmann E. 2018. Conspiracy & Populism: The Politics of Misinformation. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Crossref.

- Bessi A., Scala A., Rossi L., Zhang Q, Quattrociocchi W. 2014. “The Economy of Attention in the Age of (Mis)Information.” Journal of Trust Management 1(1), 12. Crossref.

- Bisbee J., Lee D. D. I. 2022. “Objective Facts and Elite Cues: Partisan Responses to COVID-19.” The Journal of Politics 84(3):1278–1291. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Broniatowski D. A., Simons J. R., Gu J., Jamison A. M., Abroms L. C. 2023. “The Efficacy of Facebook’s Vaccine Misinformation Policies and Architecture During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Science Advances 9(37):eadh2132. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Broockman D., Kalla J. 2022. “The Manifold Effects of Partisan Media on Viewers’ Beliefs and Attitudes: A Field Experiment With Fox News Viewers.” OSF Preprints 1:1–42.

- Carlson M. 2020. “Fake News as an Informational Moral Panic: The Symbolic Deviancy of Social Media During the 2016 US Presidential Election.” Information, Communication & Society 23(3):374–386. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Castanho Silva B., Vegetti F., Littvay L. 2017. “The Elite Is Up to Something: Exploring the Relation Between Populism and Belief in Conspiracy Theories.” Swiss Political Science Review 23(4):423–443. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Cordonier L., Brest A. 2021. “How Do the French Inform Themselves on the Internet? Analysis of Online Information and Disinformation Behaviors.” PhD Thesis. Fondation Descartes.

- Crouch C. 2019. “Post-Democracy and Populism.” The Political Quarterly 90(S1):124–137. Crossref.

- Del Vicario M., Bessi A., Zollo F., Petroni F., Scala A., Caldarelli G., Stanley H. E., Quattrociocchi W. 2016. “The Spreading of Misinformation Online.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(3):554–559. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Döring H., Manow P. 2020. “ParlGov 2020 Release.” Harvard Dataverse V1.

- Engesser S., Ernst N., Esser F., Büchel F. 2017. “Populism and Social Media: How Politicians Spread a Fragmented Ideology.” Information, Communication & Society 20(8): 1109–1126. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Freelon D., Wells C. 2020. “Disinformation as Political Communication.” Political Communication 37(2):145–156. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Gaber I., Fisher C. 2022. “Strategic Lying: The Case of Brexit and the 2019 U.K. Election.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 27(2):460–477. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Gallotti R., Valle F., Castaldo N., Sacco P., De Domenico M. 2020. “Assessing the Risks of ‘Infodemics’ in Response to COVID-19 Epidemics.” Nature Human Behaviour 4(12):1285–1293. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Grinberg N., Joseph K., Friedland L., Swire-Thompson B., Lazer D. 2019. “Fake News on Twitter During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” Science 363(6425):374–378. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Guess A., Nagler J., Tucker J. 2019. “Less Than You Think: Prevalence and Predictors of Fake News Dissemination on Facebook.” Science Advances 5(1):eaau4586. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Haller A., Holt K., De La Brosse R. 2019. “The ‘Other’ Alternatives: Political Right-Wing Alternative Media.” Journal of Alternative & Community Media 4(1):1–6. Crossref.

- Hameleers M. 2020. “Populist Disinformation: Exploring Intersections Between Online Populism and Disinformation in the US and the Netherlands.” Politics and Governance 8(1):146–157. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Hameleers M. 2023. “Disinformation as a Context-Bound Phenomenon: Toward a Conceptual Clarification Integrating Actors, Intentions and Techniques of Creation and Dissemination.” Communication Theory 33(1):1–10. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Hameleers M., Brosius A., Marquart F., Goldberg A. C., van Elsas E., de Vreese C. H. 2022. “Mistake or Manipulation? Conceptualizing Perceived Mis- and Disinformation Among News Consumers in 10 European Countries.” Communication Research 49(7):919–941. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Hemmer N. 2016. Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. University of Pennsylvania Press. Crossref.

- Howell L. 2013. “Digital Wildfires in a Hyperconnected World.” WEF Report 3:15–94.

- Huang H. 2017. “A War of (Mis)Information: The Political Effects of Rumors and Rumor Rebuttals in an Authoritarian Country.” British Journal of Political Science 47(2):283–311. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Jagers J., Walgrave S. 2007. “Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium.” European Journal of Political Research 46(3):319–335. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Jungherr A., Rauchfleisch A. 2024. “Negative Downstream Effects of Alarmist Disinformation Discourse: Evidence From the United States.” Political Behavior 46: 2123–2143. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Jungherr A., Schroeder R. 2021. “Disinformation and the Structural Transformations of the Public Arena: Addressing the Actual Challenges to Democracy.” Social Media + Society 7(1):205630512198892. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Jungherr A., Rodríguez G. R., Rivero G., Gayo-Avello D. 2020. Retooling Politics: How Digital Media Are Shaping Democracy. Cambridge University Press. Crossref.

- Krämer B. 2017. “Populist Online Practices: The Function of the Internet in Right-Wing Populism.” Information, Communication & Society 20(9):1293–1309. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Krause W., Cohen D., Abou-Chadi T. 2023. “Does Accommodation Work? Mainstream Party Strategies and the Success of Radical Right Parties.” Political Science Research and Methods 11(1):172–179. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Lasser J., Aroyehun S. T., Simchon A., Carrella F., Gracia D., Lewandowsky S. 2022. “Social Media Sharing of Low-Quality News Sources by Political Elites.” PNAS Nexus 1(4):pgac186. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Lührmann A., Düpont N., Higashijima M., Kavasoglu Y. B., Marquardt K. L., Bernhard M., Döring H., Hicken A., Laebens M., Lindberg S. I., Medzihorsky J., Neundorf A., Reuter O. J., Ruth– Lovell S., Weghorst K. R., Wiesehomeier N., Wright J., Alizada N., Bederke P., Gastaldi L., Grahn S., Hindle G., Ilchenko N., von Römer J., Pemstein D., Seim B. 2020. “Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V–Party) Dataset V1.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/data/v-party-dataset

- Mair P. 2023. Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. Verso Books.

- March L. 2017. “Left and Right Populism Compared: The British Case.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19(2):282–305. Crossref. Web of Science.

- McIntyre L. 2018. Post-Truth. MIT Press. Crossref.

- Mitchell A., Gottfried J., Stocking G., Walker M., Fedeli S. 2019. “Many Americans Say Made-Up News Is a Critical Problem That Needs to Be Fixed.” Pew Research Center 5:2019.

- Mosleh M., Rand D. G. 2022. “Measuring Exposure to Misinformation From Political Elites on Twitter.” Nature Communications 13(1):7144. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Motta M., Hwang J., Stecula D. 2023. “What Goes Down Must Come Up? Pandemic-Related Misinformation Search Behavior During an Unplanned Facebook Outage.” Health Communication 39:1–12. Web of Science.

- Mouffe C. 2019. “The Populist Moment.” Simbiótica. Revista Electrónica 6(1):6–11.

- Mudde C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39(4):541–563. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Munger K. 2020. “All the News That’s Fit to Click: The Economics of Clickbait Media.” Political Communication 37(3):376–397. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Nagle A. 2017. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. John Hunt Publishing.

- Nielsen R. K. 2016. “The Business of News.” The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism. Sage London; Thousand Oaks, CA, 51–67. Crossref.

- Nyhan B. 2020. “Facts and Myths About Misperceptions.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(3):220–236. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Osmundsen M., Bor A., Vahlstrup P. B., Bechmann A., Petersen M. B. 2021. “Partisan Polarization Is the Primary Psychological Motivation Behind Political Fake News Sharing on Twitter.” American Political Science Review 115(3):999–1015. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Pedersen M. A., Albris K., Seaver N. 2021. “The Political Economy of Attention.” Annual Review of Anthropology 50:309–325. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Recuero R., Soares F. B., Vinhas O. 2021. “Discursive Strategies for Disinformation on WhatsApp and Twitter During the 2018 Brazilian Presidential Election.” First Monday 26(1):1–16.

- Schroeder R. 2019. “Digital Media and the Entrenchment of Right-Wing Populist Agendas.” Social Media + Society 5(4):205630511988532. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Sharma K, Seo S., Meng C., Rambhatla S., Dua A., Liu Y. 2020. “COVID-19 on Social Media: Analyzing Misinformation in Twitter Conversations.” arXiv:2003.12309. http://arxiv.org/abs/2003.12309

- SSRS (2023) CNN Poll on Biden, Economy and Elections. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23895856-cnn-poll-on-biden-economy-and-elections

- Törnberg P. 2018. “Echo Chambers and Viral Misinformation: Modeling fake news as complex contagion.” PloS One 13(9):e0203958. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Tsfati Y., Boomgaarden H. G., Strömbäck J., Vliegenthart R., Damstra A., Lindgren E. 2020. “Causes and Consequences of Mainstream Media Dissemination of Fake News: Literature Review and Synthesis.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44(2):157–173. Crossref.

- Tucker J. A., Guess A., Barberá P., Vaccari C., Siegel A., Sanovich S., Stukal D., Nyhan B. 2018. “Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation: A Review of the Scientific Literature.” SSRN [Preprint]. Crossref.

- Van Kessel S., Sajuria J., Van Hauwaert S. M. 2021. “Informed, Uninformed or Misinformed? A Cross-National Analysis of Populist Party Supporters Across European Democracies.” West European Politics 44(3):585–610. Crossref. Web of Science.

- van Vliet L., Törnberg P., Uitermark J. 2020. “The Twitter Parliamentarian Database: Analyzing Twitter Politics Across 26 Countries.” PloS One 15(9):e0237073. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Vosoughi S., Roy D., Aral S. 2018. “The Spread of True and False News Online.” Science 359(6380):1146–1151. Crossref. PubMed. Web of Science.

- Wagner M. C., Boczkowski P. J. 2019. “The Reception of Fake News: The Interpretations and Practices That Shape the Consumption of Perceived Misinformation.” Digital Journalism 7(7):870–885. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Waisbord S. 2018. “Truth is What Happens to News: On Journalism, Fake News, and Post-Truth.” Journalism Studies 19(13):1866–1878. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Wang C., Huang H. 2021. “When ‘Fake News’ Becomes Real: The Consequences of False Government Denials in an Authoritarian Country.” Comparative Political Studies 54(5):753–778. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Wang C., Zhu J., Zhang D. 2023. “The Paradox of Information Control Under Authoritarianism: Explaining Trust in Competing Messages in China.” Political Studies 72:00323217231191399. Web of Science.

- Wardle C. 2021. “Broadcast News’ Role in Amplifying Trump’s Tweets About Election Integrity.” First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/cable-news-trumps-tweets/

- Zhu J., Wang C. 2021. “I Know What You Mean: Information Compensation in an Authoritarian Country.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 26(3):587–608. Crossref. Web of Science.

- Zimmermann F., Kohring M. 2020. “Mistrust, Disinforming News, and Vote Choice: A Panel Survey on the Origins and Consequences of Believing Disinformation in the 2017 German Parliamentary Election.” Political Communication 37(2):215–237. Crossref. Web of Science.

Originally published by The International Journal of Press/Politics (2025) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.