Surveillance was endured mostly by the lower social ranks.

By Manos Chatziathanasiou

PhD Candidate in History

University of Exeter

Abstract

This paper1 addresses new aspects of surveillance in late medieval England. New approaches to the study of the phenomenon are introduced, while a limited study puts some of the author’s suggestions to the test. The study addresses the modus operandi of political and labour surveillance focusing on late medieval English towns. Surveillance was intensified after the Black Death. Institutional and non-institutional surveillance were part of everyday life, but they were also used by the ruling elites to consolidate their power. Surveillance was endured by the lower social ranks. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that sometimes popular classes resisted surveillance or even used it to their own advantage.

Introduction

“Wherever you fall in company…Be cautious of who you sit alongside.For fear that he will report your words.Evil tongues cause much anguish…”2

These 15th-century verses gave warning that a man or a woman should be wary of what they say in the company of others as another might report theirwords and then much pain is to follow. Surveillance was not an unknown notion in the Middle Ages and although it shaped the political culture of mediaeval society it remains significantly understudied. During the 14th and 15th centuries, the dynamic of popular opinion through popular protest was growing. The ruling elites knew that popular voices were a force to reckon with. Contentious words and deeds could challenge authority or even worse lead to innovation. Surveillance was used by the ruling elites to keep the population in check.3

This paper addresses new aspects of medieval surveillance focusing on political and labour surveillance in late medieval English civic communities. Its goal is to contribute to the discussion of premodern surveillance. The introductory section addresses the nature of medieval surveillance and the significance of studying it, along with the historiographical context of the phenomenon. The first section presents new ways to approach surveillance, while the second one introduces supporting evidence. Finally, the study’s limitations and findings are summarised, and recommendations regarding future research are made.

For the purposes of this paper, I define surveillance as the means which the ruling elites used to systematically monitor the speech, the deeds, and the behaviour of the lower social ranks. However, we should be careful in employing clear-cut definitions or overly political ones as surveillance was also a socioeconomic, cultural, and administrative aspect of daily life. Medieval surveillance should neither be visualised as Michel Foucault’s panopticon nor as an Orwellian dystopia due to the fact that such understandings of surveillance do not hold up for premodern societies; premodern people conceptualised their life experiences and social environment through a communitarian ideological prism. The individual and his privacy were not dealt with the reverence they do today.4 Furthermore,medieval surveillance did not derive from an all-powerful state disciplinary mechanism; it was mutual, participatory, and self-regulatory and it required the cooperation of multiple actors, people included.5

Why Medieval Surveillance Matters

Surveillance is a remarkably topical subject. Covid-19’s political ramifications increased awareness over surveillance’s importance.6 At the same time, numerous studies have indicated the increasing impact of surveillance on the economy, society, and politics.7 Until recently, surveillance was conceptualised as the implementation of a top-down power structure by an omnipotent state-authority. However, in our time and age, the theoretical framework of surveillance has changed. Contemporary surveillance is of multidirectional, de-territorialised, participatory, and of mutual nature. It is composed of multiple private, corporate, and governmental actors operating autonomically in an interlinked network. While these forces’ relationship is hierarchical, they cooperate or compete for power. “Every observer is observed”in a new world of different forms of sur-veillance and sous-veillance.8

There have been voices which indicate a medieval origin in modern surveillance practices. In fact, in 2019 Jakob Jensen claimed that “the interplay between big tech companies, nation states’ battle for control and citizens’ participatory surveillance…resembles medieval principles of feudalism and tight social control”.9 Phillip Cerny also used the concept of Neo-medievalism to address the resemblance of the modern globalised political order to the medieval “durable disorder”.10 Thus, research on medieval surveillance will deepen our understanding on the way contemporary surveillance power structures function.

Historiography

Michel Foucault in his seminal work Discipline and Punish introduced the notion of power/knowledge and addressed the practice of surveillance, while exploring the invention of prison. In respect to premodern societies, the phenomenon has been primarily studied by early modernists mostly focusing on the dynamics of state-building.11

Medieval historiography is significantly shorter; there are only two studies which directly address medieval surveillance. Amanda Power in “Under Watchful Eyes” argued that today’s mass surveillance originated in the Middle Ages. She linked surveillance with Christian religion and the legacy of the Fourth Lateran Council. Power’s account also highlighted the self-disciplinary nature of medieval surveillance.12 Christian Liddy in “Cultures of Surveillance” argued that “late medieval English towns were surveillance societies”. Focusing onthe surveillance of illicit speech, Liddy stressed the mutual character of late medieval civic surveillance and attributedit to the authorities’ fear of popular revolt.13

It would be insightful to include various studies which indirectly addressed surveillance. Amongst the most prominent is Robert Moore’s Formation of a Persecuting Society, where he investigated the formation of a self-perpetuating persecution culture, including classification procedures, in the 12th and 13th centuries.14 James Given studied the inquisitors’ “technology of power”, including identification techniques, during the Church’s campaign against heresy in Southern France.15 Samuel Cohn and Douglas Aiton in their quest for popular protest in English medieval towns addressed the ruling elites’ growing surveillance power.16 Ian Forrest investigated the identity and role of parochial “Trustworthy men”, who supplied bishops with information on a range of different issues.17

Surveillance deserves a more distinct place in historiography, along with alessacute distinction between the medieval and early modern period that hinders the exploration of the phenomenon.Perhaps notions of continuity and change between the two periods would be a fruitful field for future research, especially regarding the 50 years between the end of the 15th century and the first half of the 16th century, which remain less studied by medievalists and early modernists alike.

Apart from being understudied, medieval surveillance suffers from England’s “splendid isolation”, that is a historiographical trend which sees England and the continent as two entirely different historical paradigms. For instance, “splendid isolation” is relatively strong with the work ofJan Dumolyn and Samuel Cohn concerning the historiographical fields of guild politics and popular protest respectively, both of which are critical to understanding urban surveillance.18 It is important to note that there are exceptions, where English and continental scholars have engaged with each other’s work. One such piece of literature isChristian Liddy’s and Jelle Haemer’s comparative approach on popular politics.19

I am not advocating for an interpretive equation between continental and English history. It is true that the massive phenomena of popular protest were not as endemic in England as in Flanders. Neither did the English craft guilds hold the same amount of official political power as their counterparts in Southern Germany and in Flanders did, nor did the English lower social ranks storm in organised protest in the public sphere as often as in Florence or Bruges.20 However, common patterns can be observed. Apart from institutional manifestations, the underlying sociopolitical dynamic of the above-mentioned phenomena should also be considered as it might bear more similarities than historiography suggests. In other words, continental historians provide the means for exploring English history and historians of medieval England ought to use them, if applicable.

In what historical context did surveillance arise? What kind of sources should we investigate? Where and when should we look for surveillance? The present article delves into approaches to medieval surveillance.

Historical Context(s): Crisis?

Surveillance is most prominently observed during times of historical crisis.21 Previous research steered us towards political crises as a promising field for studying surveillance. Samuel Cohn and Douglas Aiton illustrated the growth of surveillance, when addressing London’s greatest mayoral dispute between Nicholas Brembre and John Northampton during the 1380’s and 1390’s and the prosecution of Lollardy.22 Additionally, according to Christian Liddy, political surveillance originated in elites’ anxieties over popular uprising.23

Whether it was fear, prevention, or an excuse to consolidate power, surveillance increased social control. This is true regarding either specific historical events or broader historical phenomena. For example, Cohn and Aiton came across intensified surveillance during Brembre’s suppressive regime in London.24 In a broader perspective, it could not be a mere coincidence that a growing political gulf appeared between the lower social ranks and the ruling elites during a time of intensified surveillance, namely during the 15th and 16th centuries.25

While the context of political crisis appears suitable, it is imperative to consider alternative pathways for exploring medieval surveillance. I advocate for viewing surveillance as a reflection of society and vice versa. In this regard, an underexplored context for researching surveillance is labour. Therefore, I propose to investigate the processes of surveillance through the lens of labour relations and labour structures.

There are many reasons why the world of labourconstitutes a promising field for exploring surveillance. First and foremost, the study of post-plague labour encompasses the concept of crisis. Following the Black Death, acute labour shortages occurred, which led to skyrocketing wages and consequently gave rise to an extended labour and social crisis. In response to this crisis, the ruling elites implemented harsh labour laws. Furthermore, these new labour regulations affected a broad and socially diverse spectrum of the labour world, both in urban and rural areas, including labourers and servants, as well as apprentices and journeymen. At the same time, these statutes financially benefited a diverse group of employers by attempting to establish a cheap and disciplined labour pool. The labour regulations mandated compulsory service, set prices, wages, and working hours. Additionally, they restricted wage-earners’ mobility and regulated both work conditions and workers’ leisure time.26

Another well-established factor that validates post-plague labour as a suitable context for researching surveillance is politics. The labour legislation had a profound political dimension since it claimed an unprecedented degree of control over the realm’s lower social ranks and redefined their position in society. Questioning the labour laws meant contesting the elites’ authority.27

Labour also constituted a distinct field of socialising in late medieval urban society. In fact, labour as a social locus produced greater social power compared to other loci. Given that power is intrinsically linked to information, the field of labour presents a compelling context for the examination of surveillance practices.28 But why were social relations forged through labour of greater significance? Places of work, like the workshop, the shop, or the market, constituted spaces of daily social, economic and political interaction. Furthermore, guilds in late medieval England were both numerous and influential in constructing social and political networks and they were interlinked with the world of labour, whether they were crafts or fraternities.29 Additionally, following the labour crisis, the social and cultural capital associated with labour increased in a society where labour was in short supply. Finally, labour was a primary field of social conflictduring this time, where authority and power were realised, questioned and challenged.

The Right Time and Place

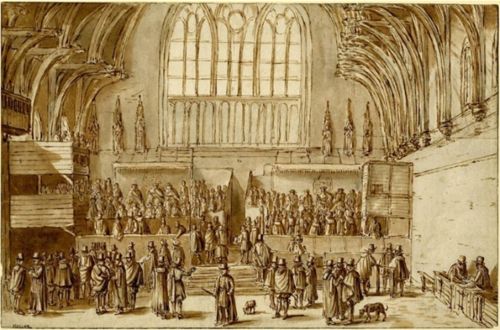

When and where should we look for surveillance? England’s civic communities are an ideal research locus. Political power was distributed between multiple actors in the late medieval English town, mainly between the Crown and the civic councils. The civic council was the principal institution of power consisting of merchants, gentry and, after 1350, master craftsmen.30 All the above facilitated a complex nexus of social, administrative, and labour apparatus, which allowed a sophisticated surveillance culture to flourish.

Moving on to the most suitable period for researching surveillance, Christian Liddy has convincingly argued that “there was a qualitative and quantitative expansion of surveillance, and changes in modes of data collection and record-keeping, from the last quarter of the fifteenth century”.31 Sarah Rees Jones has also argued that during the second half of the 15th century, new forms of civic record-keeping emerged, focusing on monitoring, documenting, and regulating potentially dangerous political speech and conduct. However, a more primitive manifestation of surveillance, starting from the mid-14th century, is also possible. There are three reasons for this proposed shift in chronology. Firstly, the elites’ fear of a topsy-turvy world had already begun in the 1350s.32 Secondly, popular revolt became endemic in England by the 1370s.33 Finally, during the 14th century, the ruling elites of many towns sought to advance their prerogatives and limit popular consent regarding political decision-making and electoral procedures. This predicament led to significant turmoil in civic politics during both the 14th and 15th centuries.34 Thus, I propose 1350 as the starting date for researching surveillance and recommend extending the research to 1550, as the first half of the 16th century is relatively underexplored. This period presents an opportunity to examine the continuity and changes between the medieval and early modern eras.

Questions and Sources

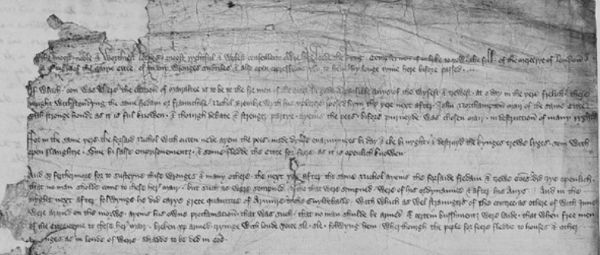

What types of sources should we consult, and what questions should we pose to them? Our initial inquiry should focus on understanding how surveillance was conducted. The most apparent sources to examine are local civic records. For instance, the minute books of civic councils constitute a promising source as they include the civic community’s statutes, royal correspondence, and craft guilds’ ordinances. Local judicial records, like the mayors’ court rolls, could also prove valuable, as well as the by-laws of local guilds. Local church courts, such as consistory courts, should not be ignored since they investigate cases of moral and social discipline. Additionally, central records are crucial for gaining insight into the Crown’s perspective. Legislative activity in the Statutes of the Realm and administrative instructions in the Patent Rolls could illuminate the subject. The same applies to central judicial records. Additionally, the Common Pleas records, which are a vast pool of digitised data including occupational information, could help us explore labour surveillance. Due to the organic connection between labour and civic politics, all of the above sources are relevant to both political and labour surveillance.

Another important question concerns the perception of surveillance and the attitudes of different social ranks towards it. The sources mentioned above shed light on the perceptions of the upper social ranks. The Parliament Rolls could also serve as an additional source, along with religious sermons and estate satire literature. The latter two could also be relevant to labour surveillance, while treatises on labour should be included as well.

What about the middle and the lower social ranks? How did they perceive surveillance? As always, the issue is that the lower strata rarely spoke for themselves. The elites assumed this role for them. Still, careful decoding of the sources with the help of academic scholarship should help us unravel popular attitudes towards surveillance; to quote Jeremy Goldberg: “the medievalist may be hampered by the paucity of evidence, but that need not prevent the question from being posed…”.35

The Present Study

Due to space constraints and the fact that this is part of ongoing research, the present study can only partially address some of the points mentioned above. Nevertheless, it is necessary to provide some evidence for the suggestions previously made. To this end, I shall investigate political and labour surveillance in late medieval towns between 1350 and 1550, focusing on the modus operandi of surveillance and its perception by the lower social ranks. This will involve the examination of the Statutes of theRealm and urban records, including minute books and judicial records. Given the study’s limited scope, I have chosen not to include a specific case study, but will instead present examples from various English towns, specifically London, York, and Coventry.

The Anatomy of Urban Surveillance

By the later medieval era, surveillance was already integratedinto central and local judicial and governance structures.It was part of the authorities’ vested interest in identifying and monitoring outsiders within local societies.For example, surveillance methods were crucial for the administrative and social functions of ward courts, tithings, and households.36

However,certain late medieval legislative initiatives indicated the Crown’s growing interest in surveillance. For instance, in 1388, the Crown issued a national inquiry into guilds, requiring masters and wardens to send information to the Chancery regarding their societies’ constitutions, properties, finances, and objectives.Undoubtedly, the national inquiry of guilds was associated with the Commons’ economic interests, as they had petitioned the Crown to confiscate the guilds’ chests to finance the war with France.37 Nevertheless, political motives also played a role in the inquiry. The newly formed regime of the Lords Appellant, which was in control at the time, was insecure. Furthermore, the inquiry was issued a few years after the Rising of 1381, when fears of popular revolt still troubled the upper social ranks and the government.

Evidence of intensified surveillance is also apparent in the use of espionage. Spies were deployed to assist the state to deal with foreign affairs. The use of spies expanded during the 14th century due to the Hundred Years’ War. On the other hand, spies were also used to detect and neutralise internal threats, particularly during the Wars of the Roses.38 Thomas More observed at the end of King Henry VII’s reignthat:”No longer does fear hiss whispered secrets in one’s ear, for no one has secrets either to keep or to whisper. Now it is a delight to ignore informers. Only ex informers fear informers now.“39 Additionally, espionage was employed to monitor and manipulate public opinion.40 For instance, in 1537,Sir John Russell, believed he could depend on certain “moost discrete” persons to know about the state of “comons herts”.41 In a case of manipulating popular opinion in 1494, Edward Cyver, a hatmaker, was arrested in London for allegedly travelling to coastal towns to persuade people that Henry Tudor was not their legitimate king.42

The expansion of the legal construct of treason during the 14th and 15th centuries also must have facilitated surveillance. According to John Bellamy, since 1352 imagining the King’s death was defined as treason.43 During the reign of Henry IV uttering words against the king or words causing insurrection were also considered treason.44 In the 15th century dissolving the cordial love between the Crown and its subjects became increasingly treasonous, thus expanding the scope of treason.45 It should be noted that legal constraints did not stop the authorities fromexpanding the scope of treason whenevernecessity dictated it, especially during popular revolts.46

Political Surveillance

The Crown’s most decisive endorsement of political surveillance can clearly be observed in its correspondence with the realm’s civic ruling elites. King Edward IV’s anxiety is particularly apparent in his communication with the civic council of Coventry in 1463. He was worried about “unfitting and seditious tales and language” turning his subjects “to rumor and commotion”. Coventry’s aldermen were “by all ways and means” and in “full…diligence” to find and arrest “such seditious folk”.47 Answering a similar royal call in 1477, the mayor of Coventry summoned the Common Council of 48 and the constables of every ward in the city. He instructed them to sweep the town searching for “any suspect person…having suspicious language”, among other things, and report back to him immediately.48

Illicit speech was not the only threat; written words could also prove dangerous. In 1485, the Crown was set to hunt down those who “enforce themself daily to sow the seed of noise...”. The civic authorities of York were to look out for those who spread “false and abominable language and lies”. Some did so “by bold and presumptuous open speech” and “some by setting up of bills”.49 It was issued that “whoever first find any seditious bill set up in any place he take it down and without reading it or showing the same to any other person” deliver it immediately to the authorities.50

Civic rulers faced their own challenges. However, with assistance from appropriate individuals, they could identify troublemakers. In 1477, a butcher, named Thomas Knayton, presented himself to the mayor of York and told him that he had heard Petre Kyrke Litell saying that “John Tong, now being Mayor, was not able to be Mayor of this Worshipful City”.51 As the next case will demonstrate, the threat did not

always originate from the lower social strata (see the occupation of the accused). Moreover, the urban household functioned as an extension of the public sphere rather than as a private sanctuary. In London, in 1355, a vintner, named Roger Toroldused “opprobrious words” against the mayor “…in the house of William Brangwayn in the Ward of Langbourne…” in the presence of others “who repeated the words to the Mayor the following day”.52 Furthermore,the mayoral office did not monopolise the citizens’ views on politics. In York, in 1482, John Davison “heard master William Melrig say in a place where he and others was, that he heard master Roger Brere say that regarding my Lord of Gloucester: “What might he do for the City? Nothing but to deceit us’”.53

Civic authorities had figured out that some surveilled their co-citizens not out of civic duty but in service of their own agendas. Thus, they took their measures to verify the inflow of information. In London, in 1364, John de Hakford informed the civic council that a fuller, named Richard Hay, “spread news of a conspiracy against the leading men of the City”, but Richard denied these accusations. Many were summoned to testify and found the accused not guilty. The authorities made an example out of John condemning him to stand on the pillory with a whetstone hanging from his neck.54

If not given voluntarily, information was to be extorted. In Brembre’s London, in 1386, a skinner, named Richard Sturdy, was sworn to obey the council, its officials, and his masters. He was also not to participate in illicit meetings. He was even ordered to hinder any “congregations and to warn the mayor and other officers of the city of them…”. William Mauncell was handled similarly in 1385.55

Besides mutual and self-regulatory surveillance, civic governments utilisedarchival records to monitor the population. Listings identifying urban dwellers in various capacities were produced in 15th-century London, York, and Coventry.56 In 1552, in York, it was mandated that the constables of every parish should conduct a “diligent inquire…and make a true certificate in writing of the names of…” householders, alehouse keepers, bowling alleys and vagrants.57

Labour Surveillance

Descending into the realm of labour, surveillance becomes even more present. The labour laws offer insights into surveillance aspects that have been overlooked by the majority of historians. Kelly Robertson is one of the few scholars who has recognized this connection.58 The “Laboratores” went through an unprecedented labelling and classification procedure as they were divided into smaller groups and subgroups in the Labour Statutes.To be more specific, the most significant labour statutes (1349, 1351, 1388, 1445) contained 75 terms referring to the employees’ identity (“artifices et operarii”, “seruantz” etc.) and 86 terms referring to their occupational subdivisions (“sellarii”, “pelletarii”, “carpentarii”, “cementarii” etc.).59 This thorough categorization process was not devised to the benefit of future historians, but rather to regulate and monitor labour forces.

Moreover, the stigma associated with “bad labour”60 rendered the physical and social bodies of labourers observable at work, at leisure, and in the stocks.61 Additionally, the spatial confinement of labourers along with vagrants and the undeserving poor, further facilitated their surveillance.62 The monitoring of movement, particularly since the notorious Statute of 1388,63 along with numerous indictments against those violating labour regulations, generated written records containing critical information about workers. These procedures likely enhanced the state’s efficacy in surveillance.

Following the Black Death, the national labour regulations established after 1348 redefined work ethics and explicitly detailed how labour was to be performed. Hiring was restricted to open markets, and workers were required to be confined to a single official trade.64 Additionally, the precise scheduling of work, including break times, was mandated. This systematic approach to labour regulation fostered a more rigorous culture of labour surveillance.65

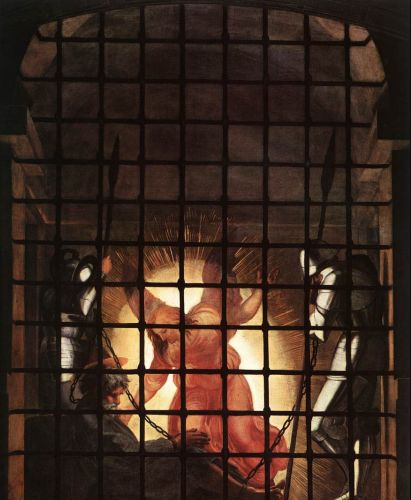

The promotion of compulsory service as a form of work through labour laws also facilitated surveillance.66 Servants and apprentices were often under the roof and under the strict authority of their masters.67 In a 1375 sermon, Bishop Thomas Brinton of Rochester articulated: “The servants of earthly lords certainly work with more delight when they can see that their lord is present. But as Scripture says: ‘The eyes of the Lord in every place behold the good and the evil.’” In this sermon, Brinton conflated the earthly and spiritual realms, using the example of a master’s surveillance of servants to illustrate the divine surveillance of morality.68

It is essential to recognize the political dimension of the employer’s authority over employees. In 1553, a young servant named Johane Swanne overheard seditious speech in a Norwich alehouse. When she reported this to her mistress, the latter advised her that “she should not keep it secret but share it with some other”. Swanne subsequently contacted the authorities, leading to an investigation.69 The mistress’s guidance in alerting civic authorities illustrates the role of employers in political surveillance and maintaining social order.

The gender and moral dimensions of employers’ authority over the workforce should also be taken into consideration. In 1492, the civic council of Coventry mandated that all women under the age of 50 cease living independently and enter the service of a master until marriage. This statute, echoing the service clause of the 1349 Labour Ordinance, aimed to secure a cheap labour force and underscore the necessity of male supervision over unmarried women living alone.70 Additionally, in 1415, London’s master-tailors reported to the mayor their inability to control journeymen who “consorted together in dwelling-houses and behaved in an unruly manner”.Subsequently, they provided the mayor with the names and locations of these troublemakers’ residences, seeking assistance to restore social order.71 Having journeymen under the same roof facilitated the masters’ control over their economic activities and behaviour, reinforcing the social and economic hierarchy.

As the relationship between master craftsmen and their workforce deteriorated after 1348, the rank-and-file gained increasing prominence within the craft hierarchy. In this context, surveillance became a central component of the administrative apparatus of craft guilds. For instance, one of the fundamental duties of guild searchers was to monitor the quality of production. However, in the wake of the Black Death, their responsibilities expanded to encompass the surveillance of deviations in speech and behaviour.72Christian Liddy notes that 15th-century guild officials, often supported by civic councils, frequently enacted measures against lower-status workers who used subversive language towards their superiors within the guild.73

In this strained work environment, journeymen and their masters frequently participated in separate fraternities. The growing mistrust of these worker societies among the masters stemmed from concerns that such groups might not always have benign intentions and, at times, functioned as covert pressure groups.74 To address these concerns, various craft guild ordinances, supported and confirmed by civic councils, established surveillance mechanisms for these employee societies. The ‘yomantaillours’ case in London in 1419 illustrates this approach: “thenceforth the serving-men or journeymen should not presume to hold conventicles in the said church or elsewhere except in the presence of the Masters of the mistery”.75 Likewise in Coventry, in 1424, there was a “dispute between master weavers and their journeymen”. One of the terms of the settlement achieved between them was that, while the journeymen had their own fraternity, they were to “…have their drinking and feast with their masters as of old”.76

Non-Institutional Surveillance: Urban space and Networking

Most historians, as demonstrated by the cases presented above, focus on the mechanisms of surveillance systematically produced and organised by established institutions of power. For example, archival systems of identification, such as London’s apprentice books, were products of institutional surveillance. Other forms of surveillance, observed in interactions within ward courts, tithings, and households, relied on both institutional frameworks and the manipulation of social relations. However, an alternative approach to understanding surveillance might involve examining methods more broadly embedded in society, rather than those confined to formal institutions. An illustrative example of non-institutional surveillance can be found in 14th-century London, where on the day of the “Feast of St Peter ad Vincula…in an irregular and foolish manner” approximately 20 craftsmen of various trades, along with a chaplain, attempted to arrange a meeting with the King. They were imprisoned but soon received a“special act of mercy”, being released “on the understanding that they would inform the officers of the City of any confederacies or conspiracies made in taverns or other secret places against the peace”.77

Although the directive originated from established institutions of power, the surveillance was to be carried out by the afore-mentionedgroup. These individuals were transformed from troublemakers into intelligence assets for the Crown and civic authorities. The authorities likely recognized the value of the arrested individuals’ social interactions and their access to various locations, which facilitated surveillance without raising suspicion. Therefore, I will employ the concepts of networking and civic space as analytical tools to further explore this case.

To decipher the group’s social network and its scope, we should focus on their social identities and the possible connections between them. The group’s social composition was far from coincidental. The world of labour and low-ranking clergy were often brothers in crime. The two social groups joined forces against the authorities regarding matters of political protest or labour conflict.78 Furthermore, the terms “confederacies or conspiracies” were also used in civic and royal records to indicate illicit meetings of political or labour character.79 Thus, the group members had ties with the world of urban disorder.

Another, less dramatic but more plausible scenario, based on the group’s social identities, is that their network of social relations was situated within the realm of urban guilds. Many guilds welcomed members of more than one craft, expanding the social scope of their membership. Furthermore, the guilds often hired chaplains and wielded much control over them. Guildsalso sought to build connections with men of the cloth to assist them in furthering their agendas, which were not always in accordance with the civic authorities’ interests. Additionally, the day of the arrest—specifically, the Feast of St. Peter ad Vincula—might have coincided with the guild’s annual feast, when all members gathered and engaged in extensive socializing.80 Consequently, the arrested individuals may have provided valuable access to the world of urban guilds and labour.

Space, namely the City’s taverns, confirms the suggestions made above. Taverns and alehouses often attracted the authorities’ attention. They were sites associated with the social profiles and activities of non-reputable people: criminals, rebels, and bad labourers.81 Taverns were viewed by the authorities as dangerous places where illicit speech, idleness, and popular insurrection flourished. Many wage-workers frequented these establishments during their free time, engaging in networking or even organizingfor nefarious purposes. During tumultuous periods, plans to overthrow the government were often devised in taverns. However, taverns were also a normal part of everyday life. Following annual feast days, guild members would gather in taverns and alehousesto socializeand discuss. Above all, taverns and alehouses served as political spaces where lower social ranks could express their views openly. Recognizing this, the authorities sought to increase surveillance in such places. For instance, in 1483, the civic council of York was informed of political discussions that took place in a local alehouse among craftsmen concerning the mayoral elections.82

Proper Attitudes towards Surveillance

Based on the available evidence, it can be argued that the growth of surveillance in late medieval England was generally tolerated. When the lower social ranks did protest or revolt, their grievances often centred on issues such as taxation rather than surveillance itself. Additionally, many individuals engaged in surveillance as part of their daily routines, either by necessity or by perceived duty to report trouble. In this context, surveillance became an integral part of their world.

Class is likely a significant variable to consider. Responses to surveillance were by no means homogeneous; different social groupsendured and responded to surveillance in varying degrees. Such attitudes were not inconsequential for the rank-and-file. To delve into the matter, it is important to consider that the middling sortsof late medieval towns—namely, male householders who held citizen rights and were relatively well-off employers—were likely more accepting of the concept of surveillance compared to their social and political subordinates, such as poorer craftsmen, unskilled labourers, and urban dwellers without citizenship. Many of the cases presented here support this claim, while Christian Lidy and Andy Wood have also stressed the pivotal role that citizens, householders and “honest men” played in surveillance.83

These middling social ranks mentioned above were surveilled both from above and from their peers. At the same time, their economic and sociopolitical capital as citizens and employers was bound to surveilling their socially inferiors. These groups, although not homogeneous, were politically self-conscious. Their political ideology combined conservative and more radical traits. The words “Let each man carry on with his trade and remain silent” capture a great deal of it.84 And while this example comes from the Low Countries, in England popular classes were also urged to “keep quiet and do their work”.85 People were aware that someone was watching and listening closely to them.According to Andy Wood, fear of surveillance is common in the sources. For instance, political chatter ended prematurely by the words: “Let us no more speak of this matter for men may be blamed for speaking the truth”.86

However, surveillance was not always passively endured. Nicholas Walker, a serjeant of York’s mayor and community—a lower officer responsible for summoning individuals to the mayor’s court—was known to frequent suspicious places after curfew. In 1416, when a sheriff confronted him at a tavern, Walker declared that he would not leave the tavern even if the mayor himself attempted to intervene.87 In addition, according to the royal Statute of 1495: “If any artificers or labourers … make or cause any assembly to assault, harm or hurt any person assigned to control and oversee them in their working…”, they would face monetary and corporal punishment.88 Since the authorities needed to legislate for the protection of those assigned to control and oversee the workers, surveillance was not only observed but was sometimes met with collective resistance.

To add to this, some individuals dared to use surveillance against their social and political superiors. In one notable case from London, an illicit fraternity of journeymen was formed in 1372. When discovered by the authorities, it was revealed that the journeymen had agreed amongst themselves that “if any of them heard any evil word spoken of any of their fellows in their absence they should inform the society thereof”.89 The workmen used counter-surveillance measures solidified by labour solidarity to protect their illicit society from the claws of the law and other ill-disposed prying eyes.

Perhaps gossip, considereddeviant by authorities and a part of daily routine by common folk, could count as a form of counter-surveillance. As Sandy Bardsley has noted, “speech was at the centre of information, culture, and power”, a statement particularly relevant to the lower social strata.90 Indeed, disorderly tongues asserted authority and incited disobedience. Chris Wickham’s examination of the social function of gossip among the medieval peasantry underscores its role as a strategy of resistance.91 After all, what could be more natural than exchanging information about bad employers, unpopular officials, unfaithful spouses or watching the ongoing neighbourhood while performing tedious labour tasks?

It appears that the civic ruling elites were also concerned about what the lower social ranks might discover. In response, they attempted to impose silence. In 1484 the civic council of York ordained that no one was to “discover the council of the Mayor and his brothers, or tells anything that is said in the Council in other places out of the Council…”.92 It seems that access to information was a contested field in civic politics. Eliza Hartich’s research on the politics of recordkeeping in 15th-century English towns also attests to this.93 Preventing information leaks was important not only regarding matters of politics, but of labour, too. In the 1370’s, Richard de Wike was accused of being a “common revealer of the secrets and counsel of the king and of his fellows”. He, along with Robert Besaunde, participated in an inquiry concerning a labourer. When Richard informed the labourer of the impending charges, the labourer responded by threatening to mutilate and kill Robert.94

Surveillance during the late medieval period appears to have been both normalised and anticipated, yet it was far from an unchallenged, top-down practice. Individuals of middling and lower social ranks were cognizant of the surveillance structures in place. They engaged with and perceived these structures in diverse and differentiated manners. Significantly, these social groups actively participated in the shaping and reshaping of surveillance, rendering it a contested field of political dynamics. Therefore, what conclusions can we draw about late medieval surveillance thus far?

Conclusion, Limitations, and Suggestions

After 1348, the turbulent social and political world of late medieval English towns facilitated the growth of labourand political surveillance. The nervous royal and civic authorities used it to strengthen their authority, while employers both inside and outside craft guilds used surveillance to control their workforce. On the other hand, surveillance structures could not have functioned without the people’s vibrant participation. Surveillance was part of daily life and routine. Nevertheless, the rank-and-file differentiated between different kinds of surveillance and varied in their attitudes towards them. The intensification of surveillance was generally felt and feared by most. It was passively endured, although some individually or collectively resisted it or used it to their benefit.

While definitive conclusions are not yet fully established, the crisis has proven to be a valuable context for examining surveillance, offering numerous illustrative examples. A focused case study could further elucidate the relationship between surveillance and crisis. Additionally, labour emerges as a promising avenue for research on surveillance, encompassing both work relations within craft guilds and beyond, though further exploration is warranted in the latter area. Finally, urban space and networkinghave demonstrated their potential as effective tools for understanding surveillance outside formal institutional frameworks.

Studying civic communities as the principal sites of surveillance, although already tested, proved a wise choice offering plentiful material. The same is true for the selected chronology. The period after the Black Death was marked by the cultivation of surveillance. Althoughfurther research is warranted to investigate systematic identification methods employed by civic authorities before the 15thcentury. Additionally, incorporating the perspectives of continental historians has enriched the analysis of surveillance structures and their connections with political culture and popular politics in England. The cities examined, characterised by their dynamic and complex guild systems, have offered significant insights. Future research could benefit from examining towns with less developed craft guild cultures, such as King’s Lynn, to broaden our understanding of surveillance in different contexts.

Surveillance was not only used coercively, but integrated into daily practices of governance, politics and labour. Thus, future research could explore the phenomenon’s distinct place in medieval political ideology. In addition, the different attitudes toward surveillance and the reasons behind them could be further explored. Regarding labour surveillance, research should focus more on the household. During the 15th century the household was seen by the upper strata as a “microcosm of the state”, where labour surveillance and correction were normalised into routine.95 Would it be too bold of us to assume the same regarding non-elite urban households? I think a lot of cases await to be discovered in the sources and we have a lot to learn about popular politics and urban political culture through the study of medieval surveillance.

Bibliography

Edited Sources

- Angelo, Raine (ed.), York Civic Records: pt. 5, vol. 110, 1946.

- Harris, D. Marry (ed.), The Coventry Leet Book: or mayor’s register, part 1, London, published for the Early English Text Society by Kegan Paul, Trunber & Co., Trench 1907.

- Luders, Alexander and others (eds.), The statutes of the realm: Vol. I-II, Dawsons of Pall Mall, London 1810-1828.

- Riley, Henry Thomas (ed.), Memorials of London and London Life in the 13th, 14th and 15th Centuries, Longmans, Green, London 1868.

- Sellers, Maud (ed.), York Memorandum Book, Part 1, 1376-1419, published for the Surtees Society: Andrews and Co, Bernard Quaritch, Durham, London 1912.

- Sharpe, R. Reginald (ed.), Calendar of Letter-Books of the City of London: 1275-1509, published by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London 1909.

- Sillem, Rosamond, Records of the Sessions of Piece in Lincolnshire, 1360-1375, Lincoln Record Society, Herford Times, Hereford 1936.

- Thomas, Arthur(ed.), Calendar of the Plea and Memoranda Rolls of the City of London: Volume 1-3, 1323-1412, Published by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London 1929.

Indicative Secondary Bibliography.

- Aiton, Douglas and Cohn, Samuel, Popular Protest in Late Medieval English Towns, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2012.

- Bennett, M. Judith, “Compulsory Service in Late Medieval England”, Past & Present, 209 (2010), pp. 7-51.

- Boone, Marc, “Urban Space and Political Conflict in Late Medieval Flanders”, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 32:4 (2002), pp. 621-640.

- Bothwell, James, Goldberg, Jeremy and Onnrod, Mark., (eds.), The Problem of Labour in Fourteenth-Century England, York Medieval Press, York 2000.

- Dumolyn, Jan, “I Thought of it at Work, in Ostend”: Urban Artisan Labour and Guild Ideology in the Later Medieval Low Countries, International Review of Social History, 62:3 (2017), pp. 389-419.

- Dumolyn, Jan and Haemers, Jelle, “Let Each Man Carry on With his Trade and Remain Silent”, Cultural and Social History, 10:2 (2013), pp.169-189.

- Dumolyn, Jan et others (eds.), The Voices of the People in Late Medieval Europe Communication and Popular Politics, Brepols, Turnhout 2014.

- Firnhaber-Baker, Justine and Dirk, Schoenaers (eds.), The Routledge History Handbook of Medieval Revolt, Routledge, London and New York 2017.

- Foronda, François (ed.), Avant le contrat social, Paris, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2011.

- Genet, Jean-Philippe (ed.), La légitimité implicite [en ligne], Éditions de la Sorbonne, Paris and Rome 2015.

- Liddy, Christian, “Popular Politics in the Late Medieval City: York and Bruges”, English Historical Review, CXXVIII:533 (2013), pp. 771-805.

- Power, Amanda “Under Watchful Eyes: The medieval origins of mass surveillance”, Lapham’s Quarterly. Available from: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/spies/under-watchful-eyes (Access: 16.05.2023).

- Pryce, Huw and Watts, John (eds.), Power and Identity in the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2007.

- Robertson, Kellie, The Laborer’s Two Bodies Literary and Legal Productions in Britain, 1350-1500, Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2006.

- Rosser, Gervase, “Going to the Fraternity Feast: Commensality and Social Relations in Late Medieval England”, The Journal of British Studies, 33:4 (1994), pp. 430-446.

- Rosser, Gervase, The Art of Solidarity in the Middle Ages, Guilds in England 1250-1550, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2015.

- Wood, Andy, ‘“A lyttull worde ys tresson”’ loyalty, denunciation and popular politics in Tudor England’, Journal of British Studies, 48:4 (2009), pp. 837-847.

See endnotes at source.

Originally published by Mos Historicus 2:1 (09.01.2024, 30-56) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.