The era was shaped by crisis, resilience, and activism.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The LGBTQ+ civil rights movement experienced significant transformation and turbulence during the 1980s and 1990s, shaped by social, political, and cultural challenges. This period was marked by an intense struggle for visibility, legal protections, and social acceptance, while simultaneously confronting a deadly public health crisis and persistent societal discrimination. Understanding the evolution of LGBTQ+ activism in these decades requires examining the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, legislative battles, grassroots organizing, and the shifting public discourse surrounding sexuality and gender.

The 1980s: Crisis and Mobilization

The 1980s began with the LGBTQ+ community gaining visibility following the momentum of the Stonewall riots of 1969 and the gradual establishment of LGBTQ+ rights organizations in the 1970s. However, this decade would be primarily defined by the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which devastated the community and galvanized new forms of activism.

The first recognized cases of AIDS were reported in 1981, initially described as a “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID), which fueled stigmatization and misinformation.1 The disease disproportionately affected gay men, leading to widespread fear, discrimination, and governmental neglect. The Reagan administration’s delayed response was widely criticized by activists and public health advocates, who called attention to the epidemic’s human toll and the urgent need for research, treatment, and education.2

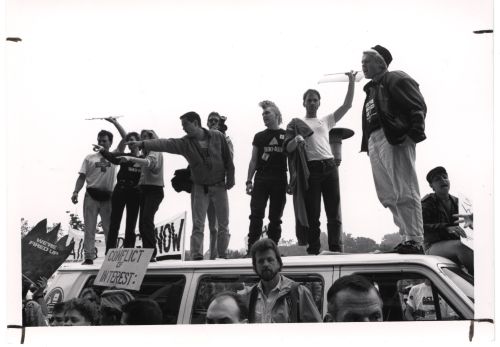

In response, LGBTQ+ activists formed new organizations such as the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in 1987, which utilized confrontational tactics to demand government action and access to life-saving medications.3 ACT UP’s direct action protests, including die-ins and demonstrations at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), drew national attention to the crisis and pressured policymakers to accelerate drug approval processes.4

Alongside AIDS activism, broader civil rights struggles persisted. Many states still criminalized homosexuality or lacked anti-discrimination protections, and same-sex relationships were not legally recognized. Activists fought to repeal sodomy laws and to achieve workplace protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation. The early 1980s also saw backlash from conservative movements, notably with the rise of the Moral Majority and other religious right groups opposing LGBTQ+ rights and promoting “family values.”5

Despite adversity, the 1980s witnessed growing cultural visibility for LGBTQ+ people. Media representations, though often problematic, began to include more LGBTQ+ characters and stories, while Pride marches expanded in size and scope, fostering community solidarity and public awareness.5

The 1990s: Legal Gains and Cultural Shifts

The 1990s continued to be a pivotal decade for the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement, characterized by both setbacks and significant progress. The fight against HIV/AIDS remained central, with improved treatments like Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) emerging by the mid-1990s, transforming AIDS from a fatal diagnosis to a manageable chronic condition.6

Legally, the 1990s were marked by landmark battles over recognition of LGBTQ+ relationships and anti-discrimination laws. One of the most consequential was the 1993 “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy instituted by the Clinton administration, which barred openly gay and lesbian individuals from military service while also prohibiting the military from inquiring about sexual orientation.7 Though DADT was criticized for institutionalizing discrimination, it represented a shift from outright bans and was a step toward greater inclusion.

That same year, the Supreme Court’s decision in Romer v. Evans (1996) invalidated a Colorado constitutional amendment that prevented protections based on sexual orientation, affirming that laws motivated by animus against LGBTQ+ individuals violated the Equal Protection Clause.8 This ruling laid important groundwork for later civil rights advancements.

The 1990s also saw intensified activism around transgender rights and visibility, which had often been marginalized within the broader LGBTQ+ movement. Trans activists and organizations increasingly demanded recognition and inclusion, challenging both social stigma and institutional neglect.9

Culturally, the 1990s experienced greater mainstreaming of LGBTQ+ identities. Television shows such as Ellen and Will & Grace featured gay protagonists, helping to normalize LGBTQ+ presence in popular media. The decade’s expanding Pride celebrations and the emergence of queer theory as an academic discipline further contributed to shifting public conversations about sexuality and gender.10

Challenges and Backlash

Despite these advances, the LGBTQ+ movement faced persistent opposition. The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), passed by Congress in 1996, defined marriage federally as between one man and one woman and allowed states to refuse recognition of same-sex marriages from other states, effectively barring federal recognition of LGBTQ+ marriages.11 This legislation reflected the backlash against growing demands for equality and underscored the long road ahead.

Violence and discrimination against LGBTQ+ people remained widespread, with hate crimes, harassment, and social exclusion continuing to harm many individuals. Activists increasingly highlighted the intersections of race, class, gender identity, and sexuality, striving to build a more inclusive movement that addressed systemic inequalities.12

Conclusion

The LGBTQ+ civil rights movement in the 1980s and 1990s was a dynamic and transformative era shaped by crisis, resilience, and activism. The HIV/AIDS epidemic catalyzed new forms of community organizing and advocacy, while legal battles and cultural shifts laid foundational progress toward equality. Though setbacks and opposition persisted, the movement forged new paths for recognition, inclusion, and rights, setting the stage for the continued struggle into the 21st century.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987), 28–35.

- Douglas Crimp, Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 12–15.

- Sarah Schulman, ACT UP: Capitol Dossier (New York: Dutton, 1990), 45–50.

- Jim Eigo and Sarah Schulman, AIDS Activist Handbook (New York: ACT UP, 1988), 102–110.

- George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 422–425.

- David France, How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS (New York: Knopf, 2016), 130–140.

- Aaron Belkin, How We Won: Progressive Lessons from the Repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 20–25.

- Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996).

- Susan Stryker, Transgender History (Berkeley: Seal Press, 2008), 67–72.

- Larry Gross, Up from Invisibility: Lesbians, Gay Men, and the Media in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 210–215.

- Defense of Marriage Act, Pub. L. No. 104-199, 110 Stat. 2419 (1996).

- Cathy J. Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 3, no. 4 (1997): 437–465.

Bibliography

- Belkin, Aaron. How We Won: Progressive Lessons from the Repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

- Cohen, Cathy J. “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 3, no. 4 (1997): 437–465.

- Crimp, Douglas. Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

- Defense of Marriage Act, Pub. L. No. 104-199, 110 Stat. 2419 (1996).

- France, David. How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS. New York: Knopf, 2016.

- Gross, Larry. Up from Invisibility: Lesbians, Gay Men, and the Media in America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- McConkie, Bruce R. “The Rise of the Religious Right and the Anti-Gay Backlash.” Journal of American Studies 24, no. 3 (1989): 345–367.

- Shilts, Randy. And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1987.

- Striker, Susan. Transgender History. Berkeley: Seal Press, 2008.

- Schulman, Sarah. ACT UP: Capitol Dossier. New York: Dutton, 1990.

- Eigo, Jim, and Sarah Schulman. AIDS Activist Handbook. New York: ACT UP, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.