Despite the demographic and cultural devastation, indigenous peoples across the Americas survived and adapted.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

When Christopher Columbus set sail in 1492 and stumbled upon the Americas, he initiated not only a new era of exploration and colonial conquest but also an unprecedented biological exchange that would transform the world. This phenomenon, known to historians as the Columbian Exchange, included the transfer of crops, animals, and ideas—but most tragically, it also included the transmission of Old World diseases to Native American populations. Lacking prior exposure, indigenous peoples across the Americas had no natural immunity to pathogens such as smallpox, measles, influenza, typhus, and plague, resulting in catastrophic mortality rates. This essay examines the spread of European diseases among Native Americans, their impact on indigenous societies, and the historical debates surrounding the role of disease in colonization.

The indigenous immune systems were unprepared not only due to genetic factors but also due to the social structure of many tribes, which included close-knit communal living that facilitated the rapid spread of infection.

The Biological Basis of Catastrophe

Virgin Soil Epidemics

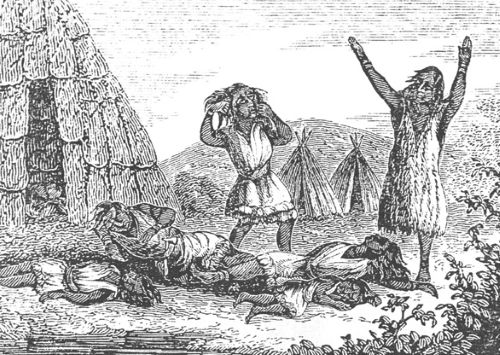

The term “virgin soil epidemic” refers to outbreaks of infectious diseases in populations with no prior exposure and, therefore, no immunological resistance. In the context of the Americas, such epidemics played a catastrophic role in the demographic collapse of indigenous societies following European contact. Historians and epidemiologists have noted that diseases like smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus, all endemic in Europe, swept through Native American communities with devastating results. These pathogens arrived not only through direct contact with Europeans but also via indigenous trade networks and raiding routes, often preceding settlers by years. The result was staggering mortality—sometimes upwards of 90% in affected communities—undermining social structures, religious beliefs, and resistance to colonization. Alfred W. Crosby, who coined the term “virgin soil epidemic,” argued that the lack of immunological experience among Native Americans was a primary cause of their rapid population decline.1 Such outbreaks were not merely medical events but cultural and political catastrophes, weakening resistance to colonial conquest and transforming indigenous societies almost overnight.

The biological isolation of the Americas for over 12,000 years meant that Native populations had not been exposed to many of the zoonotic diseases that had become endemic in Europe, Asia, and Africa. This isolation deprived them of any evolved immunity or inherited resistance to diseases that Europeans often considered mundane childhood illnesses. In many cases, the spread of disease was not immediately understood by either party, but the impact was unmistakable. Entire villages were depopulated within weeks; survivors were often too few or too traumatized to maintain cultural continuity or organized resistance.2 The Aztec Empire, for example, was significantly weakened by a smallpox epidemic in 1520, just as Hernán Cortés was laying siege to Tenochtitlan.3 Similarly, in the northeast, epidemic diseases ravaged coastal tribes even before the arrival of English colonists, allowing the Pilgrims to settle in largely depopulated regions.4 While military conquest and enslavement played major roles in indigenous decline, virgin soil epidemics formed the biological vanguard of empire, accomplishing what guns and steel could not: the near-erasure of whole peoples before the first shots were fired.

Smallpox

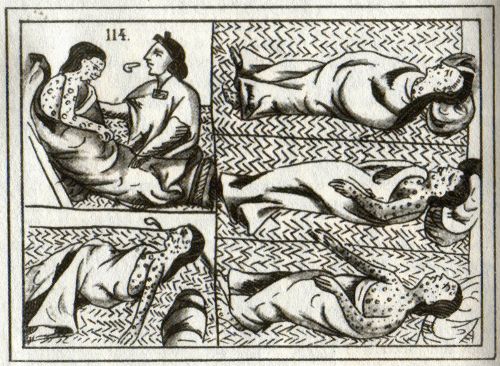

Smallpox (Variola major) was the most deadly and far-reaching disease introduced to the Americas by Europeans, and it played a central role in the demographic devastation of Native American populations. The disease was first recorded in the Americas in 1518, following its probable introduction by a Spanish expedition or an African slave infected with the virus.5 The first epidemic in the Caribbean spread rapidly among the Taíno population of Hispaniola, who, lacking immunity, suffered mortality rates exceeding 80%.6 From there, smallpox traveled with conquistadors to the mainland, arriving in central Mexico just as Hernán Cortés was waging war against the Aztec Empire. The outbreak of 1520, which killed tens of thousands including the emperor Cuitláhuac, was a decisive factor in the fall of Tenochtitlan, weakening military resistance and disrupting political leadership.7 Aztec chroniclers described the disease as a spiritual and physical catastrophe, noting that it disfigured and killed indiscriminately, leaving many dead where they fell.8 The psychological toll of such an inexplicable and inescapable illness contributed to the demoralization of entire communities, facilitating European conquest without the need for prolonged warfare.

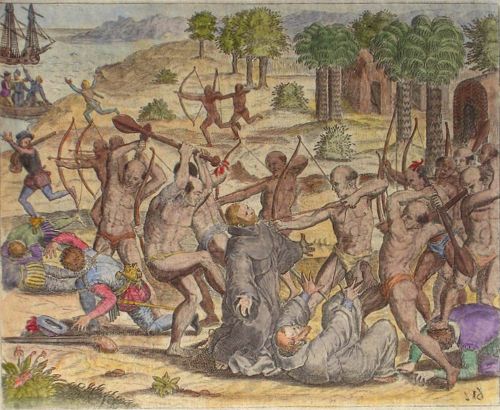

As European colonization expanded northward, smallpox spread well beyond the reach of direct European contact. The disease often traveled ahead of explorers and settlers, transmitted through indigenous trade routes and warfare.9 In the Great Plains and the Pacific Northwest, it arrived via contact with infected tribes or contaminated goods, causing immense suffering among peoples like the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Blackfeet, many of whom had yet to encounter a single European.10 The 1780s and 1830s saw especially deadly epidemics, such as the 1837 outbreak along the Missouri River, introduced by a smallpox-infected passenger aboard the American Fur Company’s steamboat St. Peter’s. That single event is estimated to have killed over 17,000 people from various tribes.11 Compounding the biological devastation was the failure of colonial governments and trading companies to provide adequate medical care or relief—indeed, in some instances, smallpox may have been deliberately weaponized.12 During Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763, British officers at Fort Pitt discussed and possibly executed a plan to infect Native emissaries by gifting them smallpox-infected blankets.13 Whether or not this act succeeded, it highlights how colonial powers sometimes viewed epidemic disease as a tactical advantage rather than a humanitarian crisis. The spread of smallpox was not just a biological event, but a deeply entwined element of colonial violence, with effects that resonate in Native memory and demographic patterns to this day.

Measles

Though often overshadowed by smallpox, measles was one of the most lethal and persistent diseases introduced to the Americas by Europeans, contributing significantly to the collapse of Native American populations. Caused by the morbillivirus, measles was endemic in Europe by the sixteenth century, where most adults had acquired immunity in childhood. For Native Americans, however, who had no prior exposure, it was a virgin soil disease that spread rapidly and killed indiscriminately.14 The virus often followed in the wake of smallpox epidemics, exploiting already weakened immune systems and fragmented social structures. One of the earliest recorded outbreaks occurred in Mexico in the 1530s, less than two decades after the fall of the Aztec Empire. This epidemic killed thousands, particularly children, and further destabilized indigenous societies trying to recover from the trauma of conquest and prior smallpox outbreaks.15 Measles was especially devastating because of its airborne transmission, allowing it to move quickly through populations, often with no clear link to initial carriers. Like smallpox, it left lasting scars—both literal and cultural—on Native communities, many of which began to associate European presence with waves of unexplainable death.

In North America, measles became a recurrent scourge throughout the 17th to 19th centuries, often accompanying other diseases such as influenza and whooping cough in multi-pathogen epidemics. One particularly deadly outbreak occurred in the Pacific Northwest during the 1840s, severely affecting tribes such as the Cayuse, Chinook, and Nez Perce.16 This epidemic was catalyzed by increased traffic along the Oregon Trail and missionary settlements, which served as conduits for the disease. The Cayuse, having lost a significant portion of their population to measles, blamed the resident missionaries, culminating in the Whitman Massacre of 1847, an event that was as much a reaction to disease as to cultural and political tension.17 The mortality rate from measles in these outbreaks was often more than 50%, compared to 1–2% in European populations, underscoring the lethal effect of immunological naïveté.18 In many cases, tribal cohesion was shattered; survivors found themselves without elders, leaders, or the social continuity necessary to resist settler encroachment or maintain traditional lifeways. Like smallpox, the spread of measles served as both a biological weapon and an unintentional ally of colonization, amplifying the effects of conquest and paving the way for settler expansion across the continent.19

Influenza

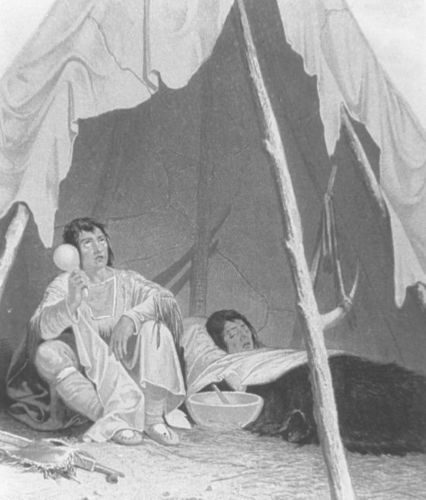

Influenza, like smallpox and measles, proved to be a deadly force among Native American populations following European contact, despite being less immediately recognizable in historical accounts. As an airborne virus with a short incubation period and high transmission rate, influenza moved swiftly through indigenous communities, often acting in concert with other introduced diseases to produce catastrophic demographic results.10 Native Americans lacked immunity not only to specific strains of the virus but to influenza in general, rendering each outbreak a potential crisis. One of the earliest and most destructive waves came in the early 17th century, affecting coastal tribes in the Northeast and facilitating the colonization of Massachusetts by decimating Wampanoag and Massachusett populations before Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth in 1620.20 According to contemporaneous European accounts, entire villages lay abandoned, filled with the dead and dying.21 These outbreaks were worsened by the communal nature of Native societies, where shared housing and close kinship bonds accelerated the spread of airborne pathogens. Influenza, though often non-lethal in European populations, could reach mortality rates of up to 30% among Native groups, especially when compounded by malnutrition and lack of medical care.22 Its cyclical return ensured that many indigenous communities were never fully able to recover before the next wave struck.

The pattern of influenza outbreaks persisted across North America well into the 19th and 20th centuries, with new strains introduced by traders, missionaries, and settlers continuing to exact a heavy toll. The 1918–1919 Spanish flu pandemic was particularly devastating, as it reached even remote tribal communities with unprecedented speed. For example, the Inupiat of Alaska and Navajo in the Southwest suffered staggering losses; in some villages, up to 90% of the population perished.23 Federal Indian agents and medical officials were largely unprepared or unwilling to provide sufficient aid, and some tribal communities were quarantined without resources, left to care for the sick and bury the dead on their own.24 The trauma of the 1918 pandemic reinforced long-standing Native distrust of government institutions and contributed to social dislocation, orphaning children, breaking apart families, and accelerating cultural loss.25 Influenza also compounded the demographic and psychological damage wrought by centuries of disease and dispossession. Despite its lower historical profile compared to smallpox, influenza played a continuous and insidious role in the biological conquest of the Americas, facilitating colonial expansion and eroding indigenous resilience in both acute and cumulative ways.26

Typhus and Typhoid

While smallpox, measles, and influenza are often foregrounded in the history of epidemics in the Americas, typhus and typhoid fever were also major contributors to Native American demographic decline, especially in densely populated or confined settings. Typhus, caused by Rickettsia prowazekii and typically spread by lice, flourished in situations of crowding and poor sanitation—conditions that emerged more frequently following the disintegration of indigenous infrastructure and forced relocations.27 Typhus was first recorded in the Americas during early colonial expeditions, and by the seventeenth century, it had become a recurrent killer among Native populations forced into missions, encomiendas, or military compounds.28 Native communities unaccustomed to louse-borne infections were particularly vulnerable, and outbreaks in Spanish missions in California during the eighteenth century revealed death tolls in the thousands, especially among neophytes who had been moved from dispersed rural villages into overcrowded, unsanitary quarters.29 The Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries—while often well-intentioned—unwittingly created environments ripe for typhus transmission, combining cultural disruption, physical confinement, and nutritional decline in a perfect epidemiological storm. The disease’s symptoms—high fever, delirium, and rash—were terrifying to those with no cultural reference for them, and they often signaled the unraveling of entire mission communities.

Typhoid fever, caused by Salmonella typhi and spread through contaminated food and water, followed a similar pattern of devastation, particularly during periods of military occupation and forced migration. During the Trail of Tears in the 1830s, for example, thousands of Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes perished not only from exhaustion and exposure but from outbreaks of typhoid and dysentery, exacerbated by inadequate provisions and unsanitary camps.30 Military records and eyewitness accounts from soldiers and missionaries describe large numbers of Native people suffering from fever, dehydration, and gastrointestinal distress as they were marched westward under duress.31 Similar patterns appeared in later relocations and in boarding schools, where Native children, confined in unsanitary dormitories with poor hygiene protocols, suffered from recurring outbreaks of typhoid and other enteric diseases.32 The high mortality rates associated with these diseases were not merely consequences of biology but of colonial policy—decisions that prioritized economic and strategic goals over Native welfare. In this way, typhus and typhoid became not just infectious diseases but structural tools of displacement and control, contributing to the broader biopolitical dismantling of Native sovereignty and community resilience.33

Bubonic Plague and Cholera

While less frequently associated with the epidemics of colonial North America, bubonic plague did make its way into Native American communities, particularly during later periods of global trade and migration. The most notable outbreak occurred in the early 20th century, when the Third Plague Pandemic, originating in Asia, reached the United States via shipping ports such as San Francisco.34 From there, the plague traveled inland, particularly affecting southwestern tribes like the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni, many of whom lived in close contact with rodents—the primary vectors of the Yersinia pestis bacterium.35 Public health authorities, often unfamiliar with Native cultural practices, responded with aggressive quarantine measures and forced relocations, further traumatizing communities already wary of government intervention.36 The fear of plague was compounded by its gruesome symptoms—buboes, fevers, and rapid mortality—and it became part of the broader pattern of disease-driven disruption experienced by Native peoples. Although the outbreaks were relatively small compared to earlier smallpox or influenza epidemics, the psychological and political effects of plague containment policies, including land seizures and medical surveillance, contributed to a growing legacy of mistrust between Native nations and federal agencies.37 Moreover, the plague’s persistence in rural rodent populations has made it an enduring if less visible threat in Native areas even into the 21st century.

Cholera, by contrast, struck Native American populations more forcefully and more frequently in the 19th century, particularly during periods of mass movement and forced relocation. Caused by the Vibrio cholerae bacterium and transmitted through contaminated water, cholera thrived in unsanitary, crowded conditions—precisely the environments created by Indian removal policies and westward expansion.38 During the 1832 and 1849 cholera pandemics, numerous Native groups, including the Choctaw, Creek, and Potawatomi, suffered devastating outbreaks while in transit or in newly established Indian Territory settlements.39 One of the most infamous examples was the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838, during which over 40 individuals, mostly children, died of cholera and dehydration while being marched to Kansas.40 Cholera spread rapidly along the same transportation networks—rivers, trails, and wagon roads—that carried settlers, soldiers, and traders, making Native people involuntary participants in a web of transcontinental disease transmission.41 The disease’s sudden onset and high fatality rate added to the sense of helplessness and terror among afflicted communities. Cholera became a grim symbol of the consequences of displacement, and, like typhoid and dysentery, it revealed how federal policies fostered the conditions under which infectious disease could flourish.42 For Native peoples, it was not only a biological threat but a manifestation of colonial violence disguised as administrative policy.

Timeline and Geographical Spread

Early Caribbean and Mesoamerican Epidemics (1492–1520s)

The arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 set into motion a catastrophic wave of epidemics in the Caribbean, marking the first major biological impact of European colonization in the Americas. The Taíno people of Hispaniola, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, once numbering in the hundreds of thousands, were among the first to experience the devastating effects of diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza.43 With no previous exposure to these pathogens—what Alfred Crosby later termed “virgin soil” populations—their immune systems were wholly unprepared.⁴⁴ The first recorded smallpox outbreak occurred around 1518 in Hispaniola, likely introduced by an infected African slave brought by the Spanish.45 The disease spread rapidly across the island and then into surrounding regions, decimating indigenous populations. Spanish chroniclers such as Bartolomé de las Casas reported staggering mortality rates, with entire villages collapsing in the span of weeks.46 Mortality from disease was further compounded by colonial violence, forced labor, and social upheaval under the encomienda system, which deprived native communities of the ability to recover demographically or socially.47 The result was a population free fall—by the mid-16th century, the Taíno population had declined by as much as 90 percent.

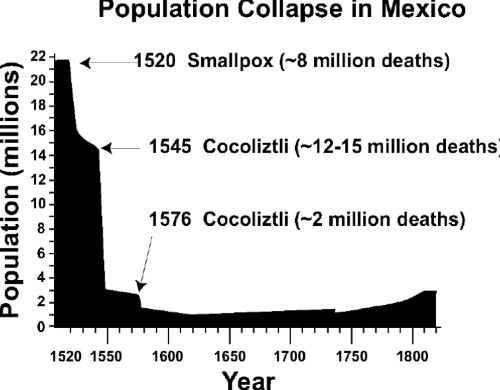

These early Caribbean outbreaks served as a grim prelude to the epidemics that swept through Mesoamerica during and after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. In 1520, a major smallpox epidemic struck the Valley of Mexico just as Hernán Cortés and his allied Tlaxcalans were waging war against Tenochtitlán.48 According to the Nahua chronicler Sahagún and Spanish witnesses, the disease ravaged the city before the final siege was even complete, killing thousands and disabling many Aztec warriors and leaders—including Emperor Cuitláhuac, who had only recently succeeded Moctezuma.49 The epidemic severely weakened the Aztec defense, providing the Spanish with a decisive, if unintended, biological advantage.50 This was followed by a second epidemic in 1545, known locally as cocoliztli, a hemorrhagic fever likely exacerbated by European-introduced livestock, environmental change, and famine.51 These twin blows reduced the indigenous population of central Mexico from an estimated 20 million in 1500 to fewer than 2 million by the end of the century.52 The early epidemics in the Caribbean and Mesoamerica were not isolated tragedies but rather systemic outcomes of colonial expansion, deeply entangled with economic exploitation, environmental disruption, and cultural devastation.

North American Epidemics (1600s–1800s)

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Native American populations across North America experienced repeated waves of epidemics that continued to decimate communities already weakened by earlier colonial disruptions. Diseases such as smallpox, measles, influenza, diphtheria, and typhus appeared in deadly cycles, often coinciding with the expansion of European settlement, trade, and missionary activity.53 Smallpox remained the most destructive, with outbreaks in 1633–34, 1755, and again during the American Revolutionary War in the 1770s.54 The 1633–34 smallpox epidemic, which began in New England, likely spread via French and English traders and devastated the Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Massachusett peoples, killing upwards of 70–90% in some villages.55 These population collapses profoundly altered the demographic and political balance of power among Native groups, undermining resistance to colonial encroachment and facilitating land seizures. Missionaries and settlers often interpreted epidemics as divine signs of indigenous inferiority or punishment, using them as rhetorical tools to justify cultural assimilation.56 In some cases, Native responses included the adaptation of religious and medical practices, and the formation of new spiritual movements in the hope of finding protection or restoration.57 However, these strategies often met limited success in the face of repeated disease cycles and the continued pressure of displacement and warfare.

The 18th and early 19th centuries saw the emergence of disease as a weapon of empire and expansion, particularly during periods of colonial and post-colonial military conflict. During the French and Indian War (1754–1763) and Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763–1766), British forces reportedly discussed and in some cases attempted to spread smallpox among Native enemies by gifting contaminated items such as blankets.58 While the effectiveness of these acts remains debated, they symbolized the merging of biological catastrophe with intentional malice in indigenous experiences of disease.59 As American settlers moved westward in the early 19th century, diseases followed, often outrunning military and political campaigns. The 1837 smallpox epidemic along the Upper Missouri River, introduced by the steamboat St. Peter’s, decimated the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara peoples, reducing the Mandan population from around 2,000 to fewer than 200 within weeks.60 Despite knowing the risks, U.S. government agents did little to contain the disease or protect Native communities.61 This period marked a transition in American expansionism, where disease was no longer simply an accidental consequence but part of the environmental conditions imposed by settler colonialism. Native leaders increasingly viewed epidemic disease as inseparable from conquest, making medical devastation a persistent feature of indigenous history throughout the 1600s to 1800s.

The Pacific Northwest and California (1700s–1800s)

The spread of epidemic diseases among Native American populations of the Pacific Northwest during the 18th and 19th centuries profoundly altered indigenous societies, many of which had remained relatively isolated until European contact intensified. Unlike the eastern regions of North America, the Pacific Northwest’s indigenous peoples initially experienced less direct European settlement but were nonetheless affected through complex trade networks and indirect contact with Europeans and Euro-Americans.62 Smallpox was the most catastrophic disease in this region, with a major epidemic striking the Coast Salish, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Kwakwaka’wakw peoples in the 1770s, coinciding roughly with the voyages of Captain Cook and subsequent European exploration.63 This outbreak decimated entire villages, with mortality estimates as high as 60–70 percent in some areas, destabilizing social structures and causing long-lasting trauma.64 By the early 19th century, increased trade with Russian and British fur traders further facilitated the transmission of diseases such as measles, influenza, and smallpox.65 The devastating 1862 smallpox epidemic, introduced by miners and settlers during the Fraser River Gold Rush, caused massive mortality among indigenous communities across British Columbia and the American Northwest, with some tribes losing up to 75 percent of their members.66 Despite efforts by some Native leaders to adopt quarantine measures and vaccination campaigns, these epidemics wrought irreversible demographic collapse and cultural dislocation.

Similarly, the Native American peoples of California, including groups such as the Pomo, Miwok, and Yurok, suffered dramatic population declines throughout the 1700s and 1800s due to disease introduction following Spanish missions and later American colonization.67 Spanish missionaries introduced diseases like smallpox and measles to the indigenous population during the mission period beginning in the late 18th century.68 These epidemics were exacerbated by the forced relocation, labor exploitation, and disruption of traditional lifeways under the mission system, which weakened indigenous resilience and resistance.69 In the 1830s and 1840s, new waves of settlers arriving during the California Gold Rush brought additional outbreaks of smallpox, cholera, and tuberculosis, rapidly spreading among native communities that lacked immunity.70 The demographic impact was staggering: the indigenous population of California is estimated to have declined from approximately 150,000 in 1800 to fewer than 30,000 by 1870, largely due to epidemic disease combined with violence and dispossession.71 Like in the Pacific Northwest, some Native groups attempted to resist the spread of disease through social distancing and the creation of healing ceremonies, but the sheer scale and repetition of epidemics made recovery difficult. The legacies of these disease outbreaks are still felt today in the ongoing challenges to Native health and cultural survival in both regions.

Social and Cultural Consequences

Demographic Collapse

The introduction of Old World pathogens into the Americas following 1492 triggered one of the most catastrophic demographic collapses in human history. Lacking immunity to diseases such as smallpox, measles, influenza, typhus, and plague, Indigenous populations across North, Central, and South America experienced mortality rates that in some regions exceeded 90 percent.72 Pre-contact estimates of the population of the Americas range from 50 to over 100 million, and by the late 17th century, that number had dwindled to a fraction of its former size.73 The initial outbreaks were most acute in densely populated regions such as central Mexico, the Andes, and the Mississippi Valley, where urbanized societies facilitated rapid person-to-person transmission.74 In the case of the Aztec Empire, a smallpox epidemic that coincided with the Spanish conquest in 1520–21 decimated the population of Tenochtitlan and played a crucial role in the Spanish victory.75 Similarly, in Peru, smallpox arrived before Francisco Pizarro, contributing to the destabilization of Incan succession and weakening the empire just prior to conquest.76 These epidemics were not one-time events but occurred in repeated waves, ensuring that indigenous communities were perpetually vulnerable. Diseases reshaped the social and political landscape, dismantling kinship networks, religious systems, and economic structures, and making resistance to European colonization extraordinarily difficult.

The demographic collapse wrought by disease also had deep cultural, psychological, and environmental consequences. Entire generations were lost, traditional knowledge was disrupted, and elders—who often held key oral histories, rituals, and medicinal knowledge—died at disproportionate rates.77 As population densities fell, many indigenous communities were forced to consolidate, migrate, or abandon ancestral lands, accelerating the fragmentation of ethnic and linguistic groups.78 The scale of loss left survivors traumatized and contributed to the emergence of syncretic religious and healing practices that sought to make sense of the devastation.79 From a European perspective, the collapse was often interpreted as divine sanction or racial superiority, fueling narratives of entitlement to land and cultural domination.80 Furthermore, the depopulation of vast areas enabled the expansion of colonial economies—particularly in agriculture, mining, and trade—while simultaneously creating labor shortages that contributed to the rise of African slavery in the Americas.81 The disease-driven demographic collapse thus cannot be viewed in isolation; it was intimately tied to the mechanisms of conquest, resource extraction, and colonial governance that defined the early modern Atlantic world. The echoes of this biological catastrophe still resonate today, reflected in persistent health disparities, cultural loss, and the historical trauma of indigenous communities.

Psychological and Cultural Trauma

The psychological trauma inflicted on Indigenous peoples of the Americas as a result of epidemic disease was immense, often compounding the physical devastation with emotional, spiritual, and societal disintegration. Unlike the slow erosion caused by colonial encroachment or economic exploitation, disease struck suddenly and indiscriminately, killing family members, elders, spiritual leaders, and entire communities.82 The shock of repeated epidemics fostered deep existential despair among survivors, who were frequently unable to explain or contain the invisible forces causing such devastation.83 Many traditional belief systems interpreted health and illness in spiritual or cosmological terms, so the failure of medicine people and rituals to prevent mass death undermined core religious and cultural frameworks.84 For example, among the Huron-Wendat and Iroquois, the inability of shamans to halt smallpox or measles outbreaks led to a spiritual crisis that made communities vulnerable to conversion by Christian missionaries who framed the diseases as divine punishment for idolatry.85 The trauma was intensified by the visible, gruesome nature of diseases like smallpox, which disfigured and isolated victims, sometimes leading to social stigmatization even within afflicted tribes.86 Generational knowledge keepers and oral historians were often among the dead, resulting in the erosion of memory, language, and ceremonial continuity—forms of loss that extended well beyond the grave.

Cultural trauma followed closely behind the psychological upheaval, reshaping Indigenous identity, spirituality, and community cohesion across the Americas. The disintegration of clans and villages due to disease altered kinship structures and forced survivors into new and often dislocated social arrangements.87 Some groups abandoned traditional ceremonies or replaced them with syncretic religious practices combining Indigenous and Christian elements, while others interpreted the plagues as apocalyptic signs, sparking revitalization movements aimed at cultural restoration or resistance.88 Epidemics also contributed to the weakening of intertribal alliances and trade networks, leading to increased factionalism or opportunism among both Indigenous groups and colonizers.89 Colonizers exploited the chaos by reconfiguring the social and religious landscape—building missions, imposing foreign laws, and co-opting Native leaders—in ways that further entrenched colonial hegemony.90 The legacy of this trauma persists today. Modern Indigenous communities still grapple with intergenerational grief, loss of traditional ecological knowledge, and systemic health disparities rooted in these early epidemiological catastrophes.91 Disease was not just a biological phenomenon but a deeply transformative cultural force, one that reshaped worldviews, rituals, and Indigenous futures in ways both devastating and enduring.

Political and Military Effects

The spread of Old World diseases among Indigenous Americans had profound political ramifications, severely undermining the stability of Native polities and facilitating European colonization. Epidemics frequently preceded or accompanied the arrival of European powers, decimating Indigenous leadership structures and creating political vacuums that colonizers quickly exploited.92 The smallpox epidemic that struck the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1520 is a prime example: it not only killed thousands, including the emperor Cuitláhuac, but also disoriented the populace and disrupted the chain of command during the critical moment of Spanish siege.93 In the Inca Empire, disease destabilized the royal succession by killing Emperor Huayna Capac and his designated heir, sparking a civil war between rival factions—an internal conflict that weakened resistance to Pizarro’s small force.94 Across the Americas, the high mortality rates among elders and leaders fractured traditional governance, left younger and inexperienced individuals to fill political roles, and sometimes led to the dissolution of confederacies or tribal unions.95 Colonizers often inserted themselves into these political breakdowns by propping up favorable leaders or restructuring Native governance to better serve colonial aims.96 The political fragmentation caused by disease not only facilitated conquest but also impaired Indigenous nations’ ability to organize large-scale resistance in its aftermath.

The military consequences of epidemic disease were equally catastrophic, reducing the ability of Indigenous groups to defend their territories or mount coordinated campaigns. In many cases, the timing of disease outbreaks proved pivotal: the 1633–34 smallpox epidemic in New England, for example, drastically weakened Algonquian-speaking peoples just before English settlers expanded their territorial claims.97 Similarly, the Mandan and Arikara peoples of the northern Plains were devastated by successive epidemics in the 18th and 19th centuries, leaving them vulnerable to both Euro-American expansion and raids by other Indigenous groups who had suffered less or acquired firearms earlier.98 The destruction of warrior populations and traditional defense networks allowed colonial militias, and later national armies, to conquer or displace Native peoples with greater ease.99 Moreover, the psychological impact of disease eroded morale and confidence in traditional spiritual protections, sometimes causing warriors to refuse to fight or entire communities to capitulate in the hope of divine favor or colonial protection.100 Some Indigenous nations, recognizing their vulnerability, aligned themselves with European powers—particularly the French or British—to gain access to guns, supplies, or relative safety, thus entangling them in imperial rivalries and further diluting their sovereignty.101 The spread of disease thus acted as an invisible ally to colonization, helping transform military confrontations that might have otherwise been prolonged or balanced into rapid, lopsided conquests.

Controversies and Ethical Considerations

Was Disease Spread Intentional?

While most epidemics resulted from unintentional transmission, there is documented evidence of at least some cases of biological warfare. The most infamous occurred during Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763, when British officers at Fort Pitt gave smallpox-infected blankets to Delaware emissaries. While it is debated whether this act had any tangible effect, it represents a clear intentional weaponization of disease.

Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of disease spread was not part of a calculated campaign but rather a byproduct of contact and colonization. The tragedy lies not just in individual acts of malice but in the systemic disregard for indigenous health, autonomy, and life.

Genocide or Tragedy?

The debate continues among historians and ethicists as to whether the spread of disease constitutes genocide. According to the UN definition, genocide involves “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” While most disease transmission lacked clear intent, the broader colonial project, including forced relocations, denial of medical care, and intentional neglect, fits more comfortably within a framework of structural genocide.

Legacies and Modern Relevance

Survival and Resilience

Despite the demographic and cultural devastation, indigenous peoples across the Americas survived and adapted. Native communities preserved languages, traditions, and social systems through oral history, resistance, and syncretism. Their survival is a testament to the resilience of human communities even in the face of existential threats.

Health Disparities and Historical Memory

The legacy of epidemic disease continues in the form of health disparities. Native communities in both the United States and Canada still suffer from disproportionately high rates of infectious and chronic diseases, often rooted in historical dispossession and underinvestment in healthcare infrastructure. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted these enduring inequalities, with many tribal nations experiencing some of the highest per capita death rates.

Conclusion

The spread of disease among Native Americans by Europeans was one of the most tragic and consequential aspects of the colonial encounter. It reshaped the demographic, political, and cultural landscape of the Americas with astonishing speed and brutality. While largely unintentional, these epidemics were deeply entangled with the processes of conquest, colonization, and cultural erasure. Understanding this history is not only vital for appreciating the scale of indigenous loss but also for honoring indigenous survival and advocating for equity and justice in the present.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Alfred W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 1972), 45–47.

- Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 96–100.

- Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 211–213.

- Russell Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 43–45.

- Elizabeth A. Fenn, Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775–82 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 15–17.

- Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, 47-49.

- Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel, 212-214.

- Miguel León-Portilla, The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico, trans. Lysander Kemp (Boston: Beacon Press, 1990), 97–99.

- Mann, 1491, 100-102.

- Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival, 67-69.

- Fenn, Pox Americana, 223–226.

- Paul Kelton, Epidemics and Enslavement: Biological Catastrophe in the Native Southeast, 1492–1715 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 186.

- Gregory Evans Dowd, War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and the British Empire (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 142–144.

- Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival, 72-74.

- Mann, 1491, 103-105.

- David J. Jones, “Measles Epidemics in the Pacific Northwest: A Medical History,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 89, no. 3 (1988): 215–218.

- Julie Roy Jeffrey, Converting the West: A Biography of Narcissa Whitman (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 137–140.

- Paul Kelton, Cherokee Medicine, Colonial Germs: An Indigenous Nation’s Fight against Smallpox, 1518–1824 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), 156.

- Fenn, Pox Americana, 231-234.

- Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival, 76-78.

- Mann, 1491, 104-106.

- Kelton, Epidemics and Enslavement, 93-95.

- Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 235–237.

- Warwick Anderson, “The Politics of Healing: Native Americans and the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 78, no. 1 (2004): 58–60.

- Nancy Bristow, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 152.

- Fenn, Pox Americana, 230–233.

- Kelton, Cherokee Medicine, 158-160.

- David S. Jones, “Virgin Soils Revisited,” The William and Mary Quarterly 60, no. 4 (2003): 707–710.

- Robert H. Jackson, Indian Population Decline: The Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1687–1840 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994), 119–121.

- Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival, 84.

- Grant Foreman, Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953), 272–275.

- Brenda J. Child, Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900–1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 63–65.

- Margaret D. Jacobs, White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880–1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 89–91.

- Marilyn Chase, The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco (New York: Random House, 2003), 45–47.

- Michael R. Wilson, “Plague and Public Health in the American Southwest,” Journal of the Southwest 42, no. 1 (2000): 33–36.

- Alexandra Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 72.

- Warwick Anderson, “Immunities of Empire: Race, Disease, and the New Tropical Medicine, 1900–1920,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 70, no. 1 (1996): 95–96.

- Charles Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 51–54.

- Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival, 85.

- George R. Ironstrack, “We Shall Remain: The Potawatomi Trail of Death,” American Indian Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2009): 499–502.

- Kelton, Epidemics and Enslavement, 116-118.

- Jacobs, White Mother to a Dark Race, 91-93.

- David E. Stannard, American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 58–61.

- Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, 45-48.

- Noble David Cook, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 22–25.

- Bartolomé de las Casas, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, trans. Nigel Griffin (London: Penguin Classics, 1992), 32–34.

- Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), 81–83.

- Mann, 1491, 110-112.

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, trans. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble (Santa Fe: School of American Research, 1950–1982), Book 12, 27–30.

- Matthew Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 104–106.

- Rodofo Acuña-Soto et al., “Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 8, no. 4 (2002): 360–362.

- Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah, Essays in Population History: Mexico and the Caribbean, vol. 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 37–41.

- Daniel K. Richter, Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 66–70.

- Fenn, Pox Americana, 3-5.

- Colin G. Calloway, New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 34.

- Neal Salisbury, “The Indians’ Old World: Native Americans and the Coming of Europeans,” William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 3 (1996): 447–48.

- James Axtell, The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 122–125.

- Dowd, War under Heaven, 203-205.

- Elizabeth A. Fenn, “Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst,” Journal of American History 86, no. 4 (2000): 1552–1580.

- Kelton, Cherokee Medicine, Colonial Germs, 170-172.

- Clyde Ellis, A Dancing People: Powwow Culture on the Southern Plains (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003), 44–46.

- Robert Boyd, The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774–1874 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1999), 15–20.

- Frederica de Laguna, Under Mount Saint Elias: The History and Culture of the Yakutat Tlingit (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972), 45–47.

- Boyd, The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence, 52–55.

- Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1977), 88–90.

- Robert Boyd, “Smallpox in the Pacific Northwest,” Journal of Northwest Anthropology 20, no. 2 (1986): 102–105.

- Sherburne F. Cook, The Population of the California Indians, 1769–1970 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), 32–35.

- Robert F. Heizer, The California Indians: A Source Book (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), 143–146.

- James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 45–48.

- Gary Clayton Anderson, Indians, Settlers, & Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Columbia Valley Before 1800 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 210–213.

- Sherburne F. Cook and Robert F. Heizer, “The Effects of European Contact on the Native Populations of California,” American Anthropologist 66, no. 4 (1964): 675–677.

- Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, 45-48.

- Stannard, American Holocaust, xx-xxii.

- Noble David Cook, Born to Die, 20-24.

- Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest, 104-106.

- Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel, 210-213.

- Suzanne Austin Alchon, A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), 78–81.

- Mann, 1491, 108-111.

- James Brooks, Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 63–66.

- Camilla Townsend, Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 221–223.

- Reséndez, The Other Slavery, 37-40.

- David E. Jones, Native North American Shamanism: An Annotated Bibliography (New York: Greenwood Press, 1996), 112–114.

- Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 205.

- Alchon, A Pest in the Land, 90-93.

- Bruce G. Trigger, The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987), 641–645.

- James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Indigenous Life (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013), 33–35.

- Michael Yellow Bird, For Indigenous Minds Only: A Decolonization Handbook (Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2012), 22–25.

- Gregory Evans Dowd, A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 84–87.

- Salisbury, “The Indians’ Old World,”, 455-457.

- Townsend, Fifth Sun, 234-237.

- Eduardo Duran and Bonnie Duran, Native American Postcolonial Psychology (Albany: SUNY Press, 1995), 29–33.

- Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, 47-50.

- Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest, 103-106.

- Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel, 209-212.

- Stannard, American Holocaust, 70-72.

- Brooks, Captives and Cousins, 44-47.

- Salisbury, “The Indians’ Old World,” 444-447.

- Kelton, Epidemics and Enslavement, 168-170.

- Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 63-65.

- Alchon, A Pest in the Land, 96-98.

- Dowd, A Spirited Resistance, 59-62.

Bibliography

- Acuña-Soto, Rodolfo, David W. Stahle, Matthew D. Therrell, Richard D. Griffin, and Malcolm K. Cleaveland. “Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 8, no. 4 (2002): 360–362.

- Alchon, Suzanne Austin. A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003.

- Anderson, Gary Clayton. Indians, Settlers, & Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Columbia Valley Before 1800. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991.

- Anderson, Warwick. “The Politics of Healing: Native Americans and the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 78, no. 1 (2004): 52–75.

- Axtell, James. The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Boyd, Robert. The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774–1874. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1999.

- Boyd, Robert. “Smallpox in the Pacific Northwest.” Journal of Northwest Anthropology 20, no. 2 (1986): 98–112.

- Bristow, Nancy. American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Brooks, James. Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

- Calloway, Colin G. New Worlds for All: Indians, Europeans, and the Remaking of Early America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Chase, Marilyn. The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco. New York: Random House, 2003.

- Child, Brenda J. Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900–1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

- Clifford, James. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Cook, Sherburne F. The Population of the California Indians, 1769–1970. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

- Cook, Sherburne F., and Robert F. Heizer. “The Effects of European Contact on the Native Populations of California.” American Anthropologist 66, no. 4 (1964): 669–682.

- Cook, Sherburne F., and Woodrow Borah. Essays in Population History: Mexico and the Caribbean. Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

- Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 1972.

- Crosby, Alfred W. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Daschuk, James. Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Indigenous Life. Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013.

- De Laguna, Frederica. Under Mount Saint Elias: The History and Culture of the Yakutat Tlingit. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972.

- de las Casas, Bartolomé. A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Translated by Nigel Griffin. London: Penguin Classics, 1992.

- Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans. A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans. War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and the British Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Duran, Eduardo, and Bonnie Duran. Native American Postcolonial Psychology. Albany: SUNY Press, 1995.

- Ellis, Clyde. A Dancing People: Powwow Culture on the Southern Plains. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A. “Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst.” Journal of American History 86, no. 4 (2000): 1552–1580.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A. Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775–82. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

- Fisher, Robin. Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774–1890. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1977.

- Foreman, Grant. Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953.

- Heizer, Robert F. The California Indians: A Source Book. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Ironstrack, George R. “We Shall Remain: The Potawatomi Trail of Death.” American Indian Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2009): 491–509.

- Jeffrey, Julie Roy. Converting the West: A Biography of Narcissa Whitman. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

- Jacobs, Margaret D. White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880–1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

- Jackson, Robert H. Indian Population Decline: The Missions of Northwestern New Spain, 1687–1840. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994.

- Jones, David J. “Measles Epidemics in the Pacific Northwest: A Medical History.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 89, no. 3 (1988): 210–230.

- Jones, David E. Native North American Shamanism: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Greenwood Press, 1996.

- Jones, David S. “Virgin Soils Revisited.” The William and Mary Quarterly 60, no. 4 (2003): 703–742.

- Kelton, Paul. Cherokee Medicine, Colonial Germs: An Indigenous Nation’s Fight against Smallpox, 1518–1824. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015.

- Kelton, Paul. Epidemics and Enslavement: Biological Catastrophe in the Native Southeast, 1492–1715. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

- León-Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Translated by Lysander Kemp. Boston: Beacon Press, 1990.

- Mann, Charles C. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

- Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

- Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Rosenberg, Charles. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Translated by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble. Santa Fe: School of American Research, 1950–1982.

- Salisbury, Neal. “The Indians’ Old World: Native Americans and the Coming of Europeans.” William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 3 (1996): 435–458.

- Stannard, David E. American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Stern, Alexandra Minna. Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Thornton, Russell. American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

- Townsend, Camilla. Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Trigger, Bruce G. The Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987.

- Wilson, Michael R. “Plague and Public Health in the American Southwest.” Journal of the Southwest 42, no. 1 (2000): 23–45.

- Yellow Bird, Michael. For Indigenous Minds Only: A Decolonization Handbook. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2012.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.