The Ottoman period was transformative for Gaza.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The city of Gaza, perched on the southern edge of the Levantine coast, has long been a crossroads of empire, religion, and commerce. Its strategic location along caravan and pilgrimage routes made it a prize for successive imperial powers, from the ancient Egyptian Pharaohs to the medieval and early modern Ottomans. When Gaza became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1517 after the defeat of the Mamluks, the city entered a new phase of its historical trajectory marked by both continuity and transformation. Over the next four centuries, Gaza would serve as a critical node in the Ottoman provincial administration, a cultural and religious hub, and a contested space between imperial authority and local autonomy. Far from being a marginal outpost, Gaza played a dynamic role in the broader political, economic, and social currents that shaped Ottoman Palestine. Here I examine the city’s evolving character under Ottoman rule, highlighting how local institutions, transregional networks, and imperial reforms interacted to define Gaza’s place in the early modern and modern Middle East.

Ottoman Conquest and Early Administration (1517–1700)

Incorporation into the Ottoman Empire

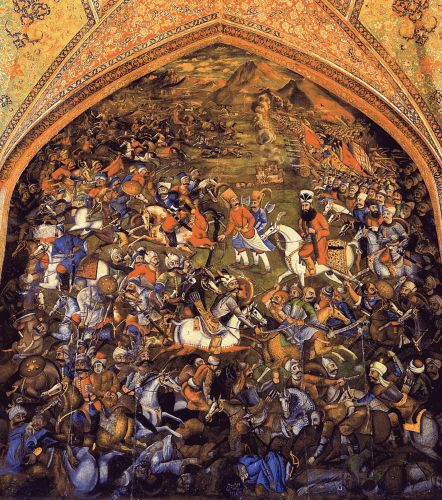

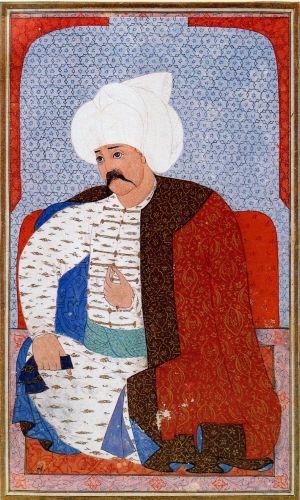

In 1516–1517, Sultan Selim I’s successful campaigns against the Mamluks led to the incorporation of the Levant into the Ottoman Empire. Gaza, formerly a Mamluk stronghold, was swiftly brought under Ottoman control.¹ The Ottomans inherited the administrative frameworks of the Mamluk system, retaining existing urban elites and integrating local Arab notables into their bureaucratic hierarchy.²

Governance and Local Power Structures

Under Ottoman administration, Gaza became part of the Sanjak of Gaza, which was a part of the larger Damascus Eyalet.³ The Ottomans ruled through a system of provincial governors (sanjakbeys and later mutasarrifs) and military-administrative divisions. Local elite families such as the Ridwan family, who governed Gaza for much of the 16th and 17th centuries, played a significant role in local governance.⁴ The Ridwans helped maintain a degree of autonomy while ensuring loyalty to the Porte.

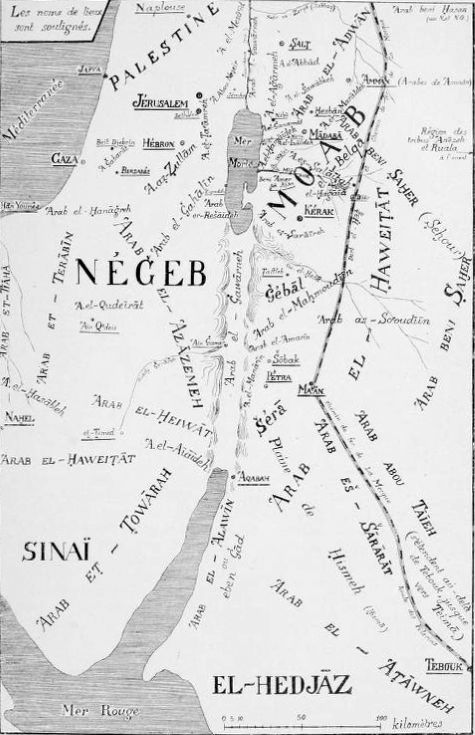

Gaza served as the capital of a district that included surrounding towns and villages, exercising considerable influence over southern Palestine and parts of the Sinai Peninsula. This period was marked by a relatively stable administration, although the city was periodically embroiled in tribal disputes and Bedouin incursions.⁵

Religious and Cultural Revival

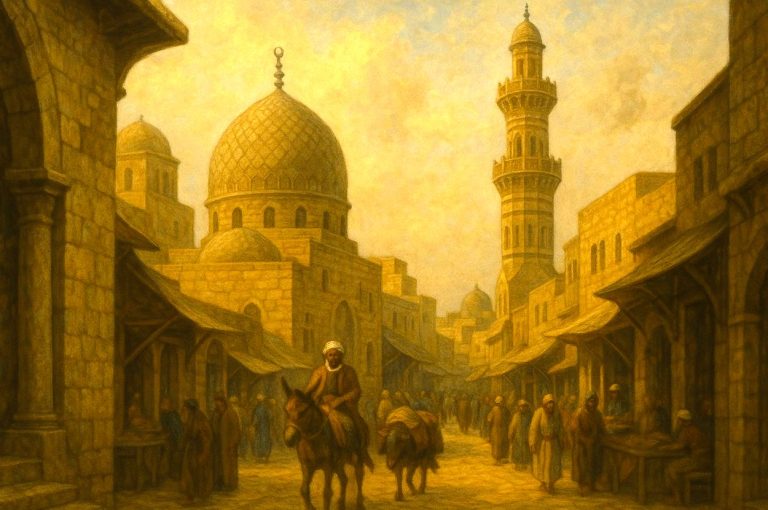

The Ottoman period saw the promotion of Sunni Islam, consistent with the broader imperial policy. Gaza was home to numerous religious institutions, including madrasas and Sufi lodges.⁶ Mosques such as the Great Omari Mosque flourished as centers of religious learning. Gaza also became a center for Islamic jurisprudence and scholarship, producing notable scholars like Khayr al-Din al-Ramli.⁷

Economic and Social Structure

Agricultural and Trade Economy

Gaza’s economy in the Ottoman period was largely agrarian. The region produced wheat, barley, olives, citrus fruits, and sesame.⁸ The surrounding rural hinterland, which extended deep into the Negev and Sinai, was critical for livestock and grain production. The Ottoman system of land tenure (including the timar and later malikâne systems) structured economic relationships between the state, tax farmers, and peasants.⁹

The city also functioned as a trade hub between Egypt, the Hijaz, and the Levant. It was a stopping point for Muslim pilgrims on the Hajj route and for merchants moving goods between Cairo and Damascus.¹⁰ Gaza’s port, however, had limited utility compared to Jaffa, and over time it diminished in maritime significance.¹¹

Urban Society

Ottoman Gaza was characterized by a layered social structure. At the top were local notables, landowners, and the ulama (religious scholars). Merchants and artisans formed the backbone of the urban economy, while the majority of the population were peasant farmers and laborers.¹² The city had a vibrant marketplace (suq) and khans that accommodated traders.

Religious minorities, including Christians and Jews, lived in designated quarters and were integrated into the economy while paying the jizya tax.¹³ While Muslims dominated political and religious life, these minorities contributed to Gaza’s social and commercial vibrancy.

Challenges and Decline (1700–1800)

Decentralization and Tribal Turmoil

By the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire experienced increasing decentralization, and local governors wielded greater autonomy. Gaza was often affected by the broader instability across Palestine. Bedouin tribes, whose control over rural areas was never fully eradicated, periodically challenged Ottoman authority and disrupted trade and agriculture.¹⁴

The weakening of central control led to power struggles between competing local families and factions. These internal conflicts, combined with the decline in trade routes due to the shift toward maritime commerce in Europe, caused a general economic and demographic downturn in Gaza.¹⁵

Natural Disasters and Famine

In addition to political instability, Gaza suffered from natural disasters and famine in the 18th century. Periodic droughts, locust infestations, and outbreaks of plague decimated the population.¹⁶ These factors exacerbated rural depopulation and contributed to the city’s relative decline in regional importance.

Tanzimat Reforms and Late Ottoman Modernization (1839–1917)

The Tanzimat and Administrative Restructuring

In the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire undertook a series of reforms known as the Tanzimat, aimed at centralizing authority and modernizing the state. Gaza was affected by these reforms, particularly in land tenure, taxation, and administrative restructuring.¹⁷ The 1858 Land Code, intended to clarify land ownership, had the effect of consolidating land in the hands of wealthy urban elites, often at the expense of peasant farmers.¹⁸

By the 1860s, Gaza became part of the Jerusalem Mutasarrifate, which answered directly to Istanbul, bypassing the provincial authority in Damascus.¹⁹ This change reflected the growing strategic importance the Ottomans placed on southern Palestine, particularly in light of increasing European involvement in the region.

European Influence and Missionary Activity

European powers, particularly Britain, France, and Germany, began expanding their influence in Ottoman Palestine through consular offices, missionary activity, and archaeological exploration.²⁰ While Gaza did not experience the same level of missionary penetration as Jerusalem or Jaffa, it was not immune to European interest.

Some missionary schools and medical missions appeared in Gaza in the late 19th century, introducing Western educational models and languages.²¹ These institutions often coexisted uneasily with traditional Islamic education systems but gradually influenced the city’s cultural landscape.

Demographic and Urban Growth

Despite previous decline, Gaza began to recover demographically and economically in the late Ottoman period. Improvements in transportation, including the construction of roads connecting Gaza to Jaffa and Jerusalem, facilitated trade.²² The city expanded beyond its old walls, and new neighborhoods, markets, and administrative buildings were constructed.

Population estimates from the late 19th century suggest Gaza had between 15,000 and 20,000 residents.²³ While still modest, this growth indicated a modest urban revival.

Gaza on the Eve of the British Conquest

By the early 20th century, Gaza had reestablished itself as a regional administrative and commercial center, although it remained overshadowed by Jerusalem and coastal cities like Jaffa and Haifa. The city maintained a strong Islamic character, with religious observance playing a central role in public life.²⁴

However, Gaza was not immune to the tensions building in Ottoman Palestine. The rise of Arab nationalism, competition among local elites, and Ottoman efforts to suppress dissent created an atmosphere of political unease. During World War I, Gaza became a strategic battleground between Ottoman and British forces, culminating in the three Battles of Gaza (1917).²⁵ The third and final battle resulted in British victory and the collapse of Ottoman control, marking the end of four centuries of Ottoman rule.

Conclusion

The Ottoman period was transformative for Gaza. From its early days as a regional capital under semi-autonomous governors, through periods of decline and renewal, Gaza’s history under Ottoman rule reflected broader trends in imperial governance, economic change, and cultural development. While often marginalized in larger historical narratives of Ottoman Palestine, Gaza’s resilience and strategic importance ensure its place in the historical consciousness of the region. The legacy of this era continues to shape the city’s identity and its enduring cultural heritage.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Halil İnalcık and Donald Quataert, eds., An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 14.

- Butrus Abu-Manneh, Studies on Islam and the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century (1826–1876) (Istanbul: Isis Press, 2001), 4–5.

- Haim Gerber, Ottoman Rule in Jerusalem, 1890–1914 (Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 1985), 17.

- Amnon Cohen, Palestine in the 18th Century: Patterns of Government and Administration (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1973), 45–47.

- Beshara Doumani, Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 39.

- Sabri Jarrar, “The Hajj Route through Palestine,” in Pilgrimage in the Middle East, ed. E. Tagliacozzo and S. Teitelbaum (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 89.

- Uriel Heyd, Studies in Old Ottoman Criminal Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), 133.

- Thomas Philipp, The Syrians in Egypt, 1725–1975 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1985), 22.

- Cohen, Palestine in the 18th Century, 66.

- Jarrar, “The Hajj Route through Palestine,” 92.

- Alexander Scholch, Palestine in Transformation, 1856–1882 (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1993), 55.

- Doumani, Rediscovering Palestine, 88.

- Eugene Rogan, Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire: Transjordan, 1850–1921 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 49.

- Cohen, Palestine in the 18th Century, 93.

- Bruce Masters, The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516–1918: A Social and Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 101.

- Ahmad Amara, Land, Law and Planning Rights in Palestine (Ramallah: Birzeit University, 2007), 63.

- Amara, Land, Law and Planning Rights in Palestine, 70.

- Scholch, Palestine in Transformation, 107.

- Gerber, Ottoman Rule in Jerusalem, 52.

- Salim Tamari, Mountain against the Sea: Essays on Palestinian Society and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 79.

- Philipp, The Syrians in Egypt, 61.

- Scholch, Palestine in Transformation, 88.

- Masters, The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 157.

- Masters, The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 169.

- Tamari, Mountain against the Sea, 119.

Bibliography

- Abu-Manneh, Butrus. Studies on Islam and the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century (1826–1876). Istanbul: Isis Press, 2001.

- Amara, Ahmad. Land, Law and Planning Rights in Palestine. Ramallah: Institute of Law, Birzeit University, 2007.

- Cohen, Amnon. Palestine in the 18th Century: Patterns of Government and Administration. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1973.

- Doumani, Beshara. Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Gerber, Haim. Ottoman Rule in Jerusalem, 1890–1914. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 1985.

- Heyd, Uriel. Studies in Old Ottoman Criminal Law. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973.

- İnalcık, Halil, and Donald Quataert, eds. An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Jarrar, Sabri. “The Hajj Route through Palestine.” In Pilgrimage in the Middle East, edited by E. Tagliacozzo and S. Teitelbaum. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- Masters, Bruce. The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516–1918: A Social and Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Philipp, Thomas. The Syrians in Egypt, 1725–1975. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1985.

- Rogan, Eugene. Frontiers of the State in the Late Ottoman Empire: Transjordan, 1850–1921. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Scholch, Alexander. Palestine in Transformation, 1856–1882: Studies in Social, Economic and Political Development. Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1993.

- Tamari, Salim. Mountain against the Sea: Essays on Palestinian Society and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.