These civilizations exhibited a keen awareness of the dangers posed by compulsive indulgence.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Substance abuse and addiction are often perceived as modern social problems, linked to industrialization, psychological stress, and the complexities of contemporary life. However, the human tendency to seek altered states of consciousness—whether for ritual, recreation, or relief—is deeply rooted in antiquity. In the ancient civilizations of Greece and Rome, the use of mind-altering substances was widespread and culturally embedded. While these societies lacked the modern terminology and medical understanding of “addiction,” their literature, philosophy, medicine, and social norms reveal a nuanced awareness of the dangers of excessive consumption. This essay explores the nature of substance use and abuse in ancient Greece and Rome, examining the substances available, their medical and recreational use, the recognition of compulsive behavior, and the ethical and social implications of addiction in these classical worlds.

Available Substances in the Classical World

Alcohol (Primarily Wine)

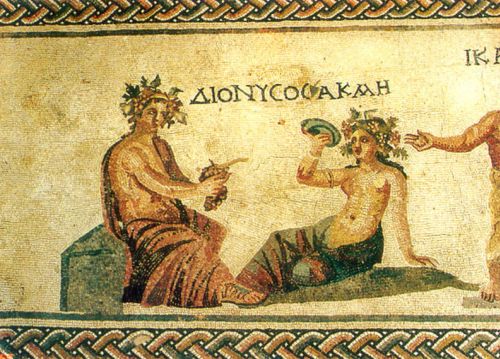

Alcohol, especially in the form of wine, played a central role in both ancient Greek and Roman societies. In Greece, wine was more than a recreational beverage; it was a symbol of civilization and culture, closely associated with the god Dionysus and the ritual of the symposium. Symposia were structured drinking parties where elite men gathered to discuss philosophy, poetry, and politics while drinking diluted wine. The Greeks typically mixed wine with water, considering the consumption of undiluted wine (akratos oinos) barbaric and uncivilized.1 The practice of dilution was a mark of moderation and self-control—qualities highly valued in Greek ethics. However, the same cultural norms that praised controlled drinking also acknowledged the disruptive potential of excessive inebriation, often associating it with a breakdown of rationality and civic virtue.

In contrast, the Romans adopted a more pragmatic and permissive attitude toward alcohol, especially wine, which was widely consumed across all social classes. Roman viticulture expanded immensely during the Republic and Empire, and wine became a staple of daily life, consumed by everyone from slaves to senators.2 Yet, despite its ubiquity, excessive drinking was still frowned upon by Roman moralists. Writers like Cato the Elder and Seneca the Younger warned of the dangers of drunkenness, portraying it as a vice that undermined self-discipline and honor.3 Roman satire also frequently targeted the drunken elite, as seen in the works of Juvenal and Petronius, who used intoxication as a metaphor for moral and social decay. Public drunkenness, while common, could be grounds for ridicule or even social ostracism, especially when it interfered with one’s duties as a citizen or paterfamilias.

The ancients may not have had a clinical concept of “alcoholism” as understood today, but they certainly recognized patterns of compulsive and destructive drinking. Philosophers and physicians alike noted how habitual excess led to loss of control, illness, and social ruin. Galen, the influential Roman physician, wrote about the physical consequences of frequent inebriation, including liver damage and cognitive impairment, and emphasized the importance of temperance for maintaining humoral balance.4 Similarly, Plato and Aristotle both discussed the moral implications of drunkenness, categorizing it as a failure of reason and self-governance.5 These observations indicate a rudimentary understanding of addictive behavior, even in the absence of modern psychological frameworks.

Cultural attitudes toward alcohol were deeply intertwined with gender and class norms. In Greece, freeborn women were generally prohibited from participating in symposia or drinking wine, which was reserved for male citizens and certain hetairai (courtesans).6 In Rome, elite women had somewhat more freedom, but heavy drinking by women was still stigmatized and associated with moral laxity.7 Slaves and the poor, meanwhile, often turned to cheap and diluted wines, sometimes to escape the harsh realities of daily life. While elite men could indulge in wine as a symbol of leisure and culture, lower-class drinking was more often viewed as a sign of degeneracy or vice. This dual standard reflects broader social hierarchies in the ancient world, where the context and manner of consumption determined whether alcohol was seen as civilizing or corrupting.

Religious and ritual use of wine further complicated the moral perception of drinking. In Greece, the Dionysian mysteries involved ecstatic rites that included the ritual use of wine to achieve spiritual liberation or divine communion.8 Similarly, Roman Bacchanalia originally functioned as religious festivals but were later suppressed by the Senate in 186 BCE amid allegations of sexual promiscuity and social disorder.9 These examples reveal that alcohol use in antiquity was not merely recreational—it was a potent symbol of both sacred and profane experiences. The tension between moderation and excess, virtue and vice, reverence and indulgence, shaped how ancient Greeks and Romans understood and responded to alcohol consumption in their societies.

Opium and Other Narcotics

The use of opium in the ancient world predates written history, but it was in the Greek and Roman periods that its pharmacological and intoxicating properties were both systematized and problematized. Derived from the sap of the Papaver somniferum poppy, opium was known for its potent analgesic, sedative, and euphoric effects. The Greeks referred to opium and poppy derivatives in both medical and mythological contexts. Homer mentions “nepenthe,” a drug said to banish sorrow and grief, which some scholars believe may have been opium or a poppy-based mixture.10 By the 5th century BCE, Greek physicians like Hippocrates recognized opium’s efficacy in treating pain, insomnia, and various ailments, though they did not yet fully understand its addictive potential.11 Nevertheless, its powerful effects made it a central feature of ancient pharmacology and, as later sources suggest, a potential substance of abuse.

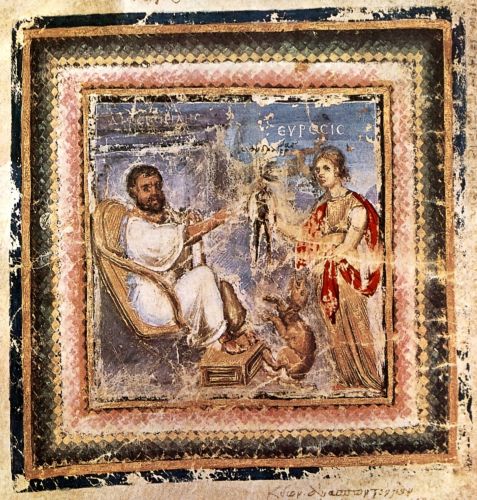

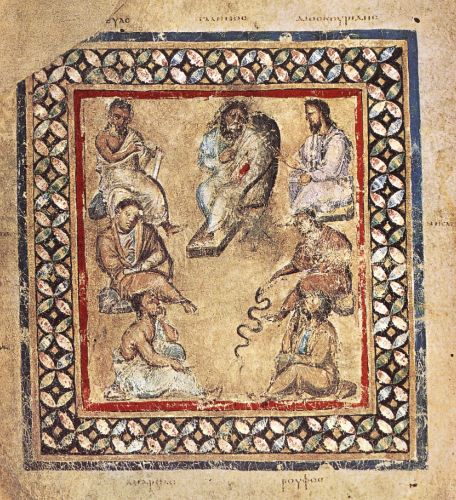

Roman engagement with opium continued the Greek tradition but further expanded its use and availability across the empire. Roman physicians such as Dioscorides and Galen documented opium’s medicinal value in great detail. Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica outlines the preparation of opium and recommends it for inducing sleep and easing pain, while Galen provides more elaborate commentary on dosage and side effects.12 Galen acknowledged that overuse could lead to dependency and even psychological disturbances, such as lethargy, melancholy, or madness.13 While these descriptions may not constitute a modern diagnosis of addiction, they highlight a growing awareness that certain substances could undermine rationality and physical health when used in excess. The ease of access to opium and other narcotics in the Roman Empire likely facilitated habitual use among both patients and pleasure seekers, particularly in urban centers where trade brought abundant exotic substances.

In addition to opium, the Greeks and Romans experimented with a range of psychoactive plants and preparations that could induce altered states of consciousness. These included mandragora (mandrake), henbane, and hemlock, which were often used in magic, ritual, or even execution.14 Some of these substances were used recreationally or ritualistically, especially by mystery cults such as those of Dionysus or Orpheus, where altered mental states were believed to bring initiates closer to divine knowledge or transcendence. While these uses were often religiously sanctioned, there were warnings against overindulgence. Philosophers like Plato cautioned against relying on drugs to escape suffering, as doing so could dull the soul’s capacity for reason and virtue.15 The ethical dimension of drug use in ancient thought often aligned with the broader Greek and Roman emphasis on sophrosyne (moderation) and rational self-control.

Despite the medical legitimacy granted to many narcotics, their abuse appears in both literature and law. The comedic plays of Aristophanes and the satirical texts of Roman authors like Petronius and Juvenal occasionally depict characters intoxicated by various means, suggesting familiarity with substances beyond wine. While these works primarily used such figures for ridicule, they also reflect broader social concerns about intoxication and escapism. Roman moralists in particular warned against the erosion of civic virtue through excessive indulgence—whether in food, sex, drink, or drugs.16 Furthermore, archaeological finds of opium residues in funerary goods and domestic containers in the Mediterranean indicate that opiates were not confined to elite or medical use but circulated widely among different strata of society.17 This evidence challenges the assumption that addiction is purely a modern condition, instead suggesting that the ancients encountered many of the same temptations and dangers of substance misuse.

Though ancient medicine lacked the modern terminology of addiction, there is little doubt that the ancients recognized a pattern of compulsive use, physical dependence, and psychological effects stemming from narcotics. Galen’s detailed writings include patients who demanded increasingly larger doses of opium, while other texts refer to people who experienced withdrawal-like symptoms.18 Ancient pharmacology manuals often included warnings about frequency and dosage, with some explicitly noting that misuse could result in physical and mental decline. Yet despite these warnings, the allure of drugs remained strong in a world where effective medical treatment was limited and suffering was common. The balance between therapeutic use and abuse was one the ancients struggled to maintain, much like today’s societies. Their experience with narcotics offers a sobering precedent for understanding addiction not as a uniquely modern affliction, but as a deeply human response to pain, trauma, and the search for relief.

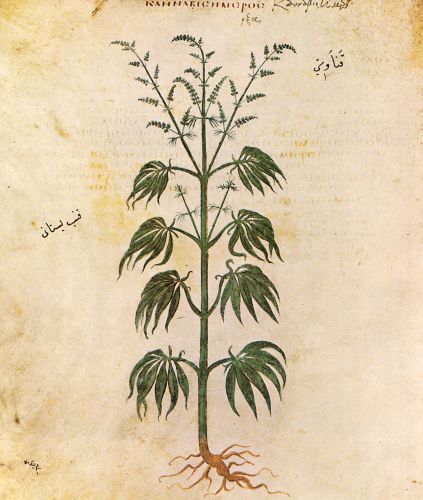

Cannabis

Cannabis, while less central to Greco-Roman pharmacology than opium or wine, was known and used in both medicinal and possibly recreational contexts in the ancient Mediterranean world. The Greek term kánnabis appears in botanical and medical texts as early as the 5th century BCE. Herodotus provides one of the earliest references to cannabis use in his description of Scythian burial rituals, where seeds were thrown onto hot stones in enclosed tents to create an intoxicating vapor.19 Though this account refers to a foreign tribe, it illustrates Greek awareness of the psychoactive properties of cannabis and hints at its ritual or recreational use. Cannabis was also listed in the works of physicians such as Dioscorides and Galen, though its applications appear to have been primarily topical or palliative rather than euphoric.20 Nonetheless, the plant’s ability to alter consciousness was not unknown, and its effects were sometimes mentioned alongside other mind-altering substances.

In Greek medicine, cannabis seeds and extracts were employed for a variety of ailments, including inflammation, earaches, and even sexual dysfunction. Dioscorides noted that the seeds, when pounded and consumed in wine, could relieve pain but might also induce “warmth and dryness,” possibly alluding to psychoactive effects.21 However, the limited references to ingestion versus topical use suggest a cultural ambivalence toward its intoxicating potential. The Greeks, who placed high value on rationality and moderation (sōphrosynē), may have viewed mind-altering drugs like cannabis with suspicion unless they served clear therapeutic functions. This is reflected in the relative scarcity of literary references to cannabis use in recreational settings, especially when compared to wine or even opium. However, the few sources that do acknowledge its psychotropic capacity imply that it could be abused, especially when consumed for escape or indulgence rather than healing.

The Roman world inherited Greek medical knowledge and expanded upon it through imperial trade and pharmacological innovation. Cannabis was included in Roman medical compendia such as those of Pliny the Elder and Galen, who described its utility in making rope, treating inflammation, and suppressing sexual desire.22 Pliny wrote that cannabis roots, boiled and applied to the skin, could alleviate arthritis and joint pain, while Galen mentioned its seeds as a mild intoxicant when eaten in cakes.23 These references suggest that while cannabis was not a central psychoactive substance in Rome, it was not entirely devoid of recreational use. Given the widespread cultivation of hemp for industrial purposes, accidental or intentional consumption of psychoactive strains likely occurred, especially among lower classes or soldiers stationed in provinces where Eastern traditions of cannabis use were more common. Yet, like the Greeks, Roman elite culture prized mental clarity and viewed intoxication with ambivalence, if not outright disdain.

There is limited but growing archaeological and textual evidence suggesting that cannabis may have been more widely used than traditionally assumed, particularly among marginalized groups or in occult practices. Magical papyri from Greco-Roman Egypt refer to herbs used in divination and spell-casting, and some scholars have speculated that cannabis was among the ingredients involved.24 Additionally, cannabis residues have been found in incense burners and ceramic vessels in areas once controlled by Rome, including the Levant and the Balkans.25 While not conclusive proof of systematic abuse, these findings indicate that cannabis was part of a broader pharmacopeia of mood-altering substances, many of which were used at the margins of official medicine or religion. As in modern times, it is likely that addiction and dependence occurred in contexts where pain relief, trauma, or existential anxiety intersected with easy access to psychoactive remedies.

Although neither the Greeks nor Romans possessed a modern understanding of cannabis addiction, they did articulate concerns about psychological dependence on intoxicants more generally. Galen, for instance, warned against habitual indulgence in pleasurable substances, which he believed weakened the soul’s rational faculties and could lead to a life of vice.26 This ethical-medical framework helps contextualize how cannabis might have been viewed: not as inherently dangerous, but as a substance requiring discipline and moderation. In this sense, ancient views align with contemporary insights into behavioral addiction, even if the ancients lacked diagnostic categories. The silence of classical sources on cannabis “addiction” per se may reflect its marginal status relative to alcohol and opium, but this silence should not be mistaken for absence. The textual and archaeological traces that do survive reveal a nuanced picture: one in which cannabis use existed at the edges of legitimacy, valued for its utility but feared for its potential to erode reason and self-mastery.

Other Psychoactive Substances

While alcohol, opium, and cannabis dominated ancient discourse on intoxicants, several other psychoactive substances were known and occasionally abused in ancient Greece and Rome. Among these were mandrake (mandragora), henbane (hyoscyamus), belladonna, and datura—plants containing tropane alkaloids that induce hallucinations, delirium, and other potent psychotropic effects. These substances were often classified as pharmaka—a term that connoted both medicine and poison, depending on use and dosage. Greek and Roman physicians, including Theophrastus and Dioscorides, described their effects in both therapeutic and ominous terms. Mandrake, for instance, was used as a sedative, anesthetic, and aphrodisiac, but also recognized for its power to “cause madness” when misused.27 Such dual characterizations made these substances simultaneously useful and dangerous—highly susceptible to both misuse and psychological dependence, especially in ritual, magical, or escapist contexts.

Henbane, known for its potent anticholinergic alkaloids (such as hyoscyamine and scopolamine), was used in medicinal concoctions for sleep and pain, but also described in some sources as capable of producing delusions and euphoria.28 Roman physicians warned of its addictive qualities, noting that repeated use could lead to mental disorientation and paranoia. In De Materia Medica, Dioscorides described henbane’s stupefying effect and advised against its casual use.29 Galen likewise noted that excessive use led to “dissolution of reason” and “madness that mimics divine possession.”30 These plant-based substances often blurred the lines between medicine, religion, and recreational intoxication. They were sometimes used in mystery cults, such as the rites of Dionysus or Hecate, where altered states were valued as a path to divine knowledge. In such settings, the potential for substance abuse—especially among initiates seeking repeated transcendental experiences—was significant, even if not categorized as “addiction” in modern terms.

Closely related to the psychoactive plants was the pharmacological class of entheogens, substances used in sacred rituals to induce visionary or ecstatic states. These included preparations from ergot-infested rye, poppy mixtures, or herbal potions with ingredients like datura or aconite, sometimes combined to intensify hallucinations.31 The Eleusinian Mysteries, one of the most secretive and sacred Greek rites, reportedly involved the consumption of a kykeon, a sacred drink whose ingredients remain unknown but are speculated to have included psychoactive compounds—possibly from ergot (a fungus with LSD-like effects).32 If this is true, then elite and state-sanctioned use of hallucinogens was embedded in aspects of Greek religiosity. Though the rituals were highly controlled, repeated participation or imitation outside these formal settings could have opened the door to unregulated usage and even dependence, particularly among mystics or spiritual seekers who desired repeated visionary states.

The ancients also experimented with combinations of psychoactive drugs, often in pursuit of deeper dreams or prolonged euphoria. Roman doctors and magicians alike concocted mixtures that combined wine with hallucinogenic or sedative herbs to create powerful, trance-inducing drinks.33 One such preparation was the theriakē, a complex compound that originally served as an antidote but evolved into a generalized panacea and, at times, a fashionable elixir for the Roman elite. Galen documented dozens of variations, some of which included small quantities of opium and other psychoactive botanicals.34 The addictive potential of such complex medicines was significant, especially given their popularity among aristocrats and the sick. Like modern prescription drug addiction, dependency could arise from legitimate therapeutic use that spiraled into habitual consumption, especially when the line between remedy and indulgence blurred.

It is worth considering the philosophical and moral responses to psychoactive substance use in antiquity. Thinkers such as Plato and Seneca warned against the soul’s enslavement to pleasure, which included intoxication through unnatural means.35 Their writings suggest a cultural awareness—not of addiction as a clinical diagnosis—but of the human susceptibility to compulsive indulgence and loss of rational autonomy. Roman Stoics, in particular, saw habitual intoxication as a form of moral decay, a failure of logos and virtus. Such concerns extended beyond wine to the broader category of “mind-altering” substances, which were associated with both the mystical and the irrational.36 While terminology such as “addiction” (addictus) in Latin originally referred to debt bondage, its metaphorical use by later writers to describe personal enslavement to pleasure hints at early recognitions of compulsive behavior. These insights, though framed in ethical rather than medical terms, contribute to our understanding of how psychoactive substance abuse—beyond alcohol, opium, or cannabis—was perceived, feared, and occasionally indulged in the ancient world.

Medical Understanding of Habit and Excess

In ancient Greece and Rome, physicians and philosophers developed a surprisingly nuanced understanding of habit (ethos) and excess (pleonexia) in relation to alcohol and drug use, even though they lacked the modern biomedical framework of addiction. Central to this understanding was the concept of balance—especially within the Hippocratic-Galenic system, where health was seen as the equilibrium of the four bodily humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile.37 Substance use, whether of wine, opium, mandrake, or other psychoactive plants, was evaluated by its effect on this balance. For example, excessive wine consumption was believed to overheat and dry the body, causing disturbances of both the body and mind.38 The medical response to such imbalances was not punitive but corrective: physicians attempted to restore humoral equilibrium through dietary regulation, purgatives, or controlled abstention, thereby revealing an early clinical approach to substance-related excess.

The writings of Hippocrates reflect a cautious attitude toward excessive indulgence, particularly with wine. In his treatise On Regimen, he observed that while wine could serve as a medicine when administered properly, it was harmful in large quantities and especially dangerous to those with naturally “hot” constitutions.39 He did not speak of addiction in a modern sense but acknowledged patterns of overuse that led to physical and behavioral changes. Later authors, such as Galen, expanded upon this medical caution by observing that repeated indulgence could lead to a type of compulsion—what he called a “second nature” (deutera physis), indicating that a habit, once formed, became physiologically and psychologically ingrained.40 This notion suggested a primitive understanding of dependence, in which repeated exposure to certain substances transformed bodily needs and desires in ways difficult to reverse.

Roman medical literature shows a parallel evolution in the understanding of habit. Celsus, writing in the early first century CE, emphasized moderation in all things, particularly diet and intoxicants.41 He warned that habitual drunkenness led to a deterioration of both moral character and physical constitution. Similarly, Galen frequently discussed how regular use of certain drugs altered one’s natural temperament and bodily function. He noted that people who used opium-based compounds over time developed resistance and required ever-increasing doses—a clear reference to tolerance.42 His awareness of both the escalation of dosage and the body’s adjustment to repeated exposure suggests an early medical model of substance dependence. Importantly, Galen did not blame the substances themselves but rather the misuse and habitual overindulgence of them, reinforcing the view that context, balance, and individual constitution were key to understanding harmful use.

One of the most insightful ancient discussions of habit and excess comes from Galen’s work On the Properties of Foodstuffs, where he described how individuals could develop a dependence not only on drugs but also on certain foods and drinks.43 He wrote about patients who became accustomed to consuming substances with “unnatural properties,” leading to conditions where their bodies rejected a return to healthier regimens. This understanding aligns with his concept of pexis, the process by which the body habituates to substances over time. Galen’s idea was not just physiological but moral and psychological; he saw habit as a threat to the self’s rational governance and an obstacle to health. The fact that he applied this concept to various substances—alcohol, opiates, and even stimulants like pepper or strong spices—demonstrates a holistic understanding of how habitual indulgence could become pathological.

While the ancients lacked a modern psychiatric model of addiction, their discussions about habit, repetition, and compulsion anticipate several aspects of contemporary theories of substance use disorder. The idea that repeated use could rewire one’s “nature,” that tolerance developed with time, and that cessation caused discomfort all point to a robust if pre-modern framework for thinking about addiction. Philosophers like Aristotle contributed to this discourse by discussing akrasia—a state in which reason is overruled by appetite—thereby connecting moral philosophy with medical concerns about excess.44 The fusion of ethical, physiological, and psychological insights in Greek and Roman thought allowed for a multifaceted understanding of substance use: one that recognized the dangers of unregulated pleasure, the plasticity of human behavior, and the importance of discipline in the pursuit of health and virtue.

Philosophical and Ethical Attitudes Toward Intoxication

Socratic and Platonic Views

The views of Socrates and Plato on intoxication, particularly in regard to wine and its effects on the soul and society, reveal a complex philosophical engagement with the themes of moderation, ecstasy, and self-control. In dialogues such as The Symposium and Laws, Plato presents Socrates as both a subject of and commentator on states of intoxication. Unlike many ancient thinkers who condemned alcohol outright or praised it without reservation, Plato used intoxication as a philosophical lens through which to examine human nature, moral development, and the tension between reason and desire.45 Socrates himself is famously depicted as remarkably sober-minded even while drinking heavily, as in Symposium, where he outlasts everyone else in the drinking party yet remains intellectually sharp.46 This suggests that for Plato, the ideal philosopher is one who can experience intoxication without being overtaken by it—someone whose rational soul governs even in states of sensory alteration.

In The Symposium, Plato presents a layered examination of intoxication, love, and divine madness. The gathering of Athenian intellectuals, each delivering a speech on eros, unfolds in an atmosphere of heavy drinking. Yet the discourse itself is elevated and philosophical. Here, Plato contrasts drunken revelry with divine inspiration, suggesting that true love and wisdom are intoxicating in a spiritual, rather than corporeal, sense.47 Socrates claims to be taught by Diotima that love is a kind of ascent from physical attraction to the contemplation of pure form—an intoxication of the soul rather than the body.48 Wine, then, becomes a symbol of the lower kind of intoxication, one that risks enslaving the rational part of the soul to the appetitive. But when moderated or surpassed, it can gesture toward a higher, philosophical intoxication that leads to truth. Thus, Plato does not reject intoxication altogether but recontextualizes it within the hierarchy of the soul’s faculties.

Plato’s more direct critique of drunkenness appears in Laws, where he discusses the effects of wine on moral development and civic order. In Book II of Laws, Plato surprisingly allows for a limited role of drinking in the education of the elderly, suggesting that moderate intoxication might be a way to test virtue and strengthen self-control.49 Yet he draws sharp boundaries: youths under eighteen are to abstain entirely, and even those above that age are to drink only under supervision. Plato saw excessive drinking as a disruption of the soul’s rational harmony, leading to moral decay and the weakening of reason’s governance.50 He proposes that the state must regulate drinking just as it regulates other behaviors that affect the health of the soul. Thus, while recognizing wine’s potential for pleasure and even social bonding, Plato consistently subordinates it to the demands of philosophical self-mastery and civic virtue.

Socrates himself, in both Plato’s dialogues and other portrayals, serves as a model of stoic resistance to intoxication. In Symposium, his ability to drink without becoming inebriated is not merely a physiological oddity but a moral and philosophical symbol.51 Socrates embodies the idea that the truly wise person is impervious to external disturbances, whether pleasure, pain, or intoxication. In contrast to Alcibiades, who bursts into the party in a drunken state and confesses his emotional dependence on Socrates, the philosopher remains composed and unshaken.52 Through this dramatic juxtaposition, Plato highlights the distinction between those ruled by passion and those who rule themselves through reason. Intoxication thus becomes a test—a crucible that reveals the structure of the soul. If one can drink and remain rational, one proves mastery. If one falls into disorder, it signals a deficiency in philosophical development.

The Platonic view of intoxication hinges on the dialectic between control and surrender. Wine is not evil per se; in fact, it can mirror or even catalyze deeper truths when placed within a framework of philosophical inquiry. The Phaedrus and Ion describe forms of divine madness (mania) that lead to poetry, prophecy, and love.53 These forms are superior to drunkenness yet related to it, as all involve the suspension of ordinary consciousness. For Plato, the danger of intoxication lies not in its ecstatic nature, but in whether that ecstasy serves the ascent of the soul or its descent into chaos. Socrates, as Plato’s philosophical hero, models the ideal relationship to such states: openness without slavery, ecstasy without loss of reason. This nuanced stance helped shape later philosophical and medical ideas about substance use, emphasizing the importance of internal order over external stimulus.

Stoic and Epicurean Views

The Stoics and Epicureans, two of the most influential philosophical schools of the Hellenistic and Roman periods, held divergent yet instructive views on intoxication, rooted in their broader ethical systems. For the Stoics, whose doctrine prioritized virtue as the only true good and reason as the supreme faculty of the soul, intoxication represented a significant moral danger. To surrender to drunkenness or drug-induced pleasure was to abdicate reason’s rightful rule over the passions, and thus undermine the integrity of the self.54 Seneca, the Roman Stoic, repeatedly warned against the use of wine as an escape from reality, arguing that true freedom came not from intoxication but from rational self-mastery.55 He condemned drinking that impaired judgment and led to a state of dependency, seeing in it not only moral failure but spiritual enslavement. For Stoics, the sage maintained composure and clarity at all times; intoxication, by contrast, represented a fall into apatheia’s opposite—disorder and irrationality.

The Stoic critique of intoxication was part of a larger program of controlling the passions (pathē). According to Epictetus, a philosopher who emphasized inner freedom, a person who drinks to excess is no different from a slave, for both are governed by forces outside their rational will.56 In his Discourses, he uses the example of a banquet to illustrate how easily pleasure, especially when fueled by wine, can erode the strength of character. The loss of self-command through intoxication becomes symbolic of all external influences that draw the soul away from virtue. The goal for the Stoic is not merely abstinence but freedom from the need for intoxication. This ideal also applied to drugs, food, and all bodily pleasures—none of which should be allowed to compromise the sovereignty of the rational mind.57 Stoics were not ascetics for asceticism’s sake, but they viewed intoxication as a betrayal of reason, and therefore a betrayal of the self.

In contrast, Epicureanism, while also committed to a life of rational reflection, offered a more permissive and pragmatic view of pleasure and intoxication. Epicurus, the founder of the school, held that pleasure (hedone) was the highest good, but he carefully distinguished between necessary and unnecessary pleasures, and between pleasures that led to tranquility (ataraxia) and those that brought pain.58 Moderate drinking was not inherently evil in his system, so long as it did not lead to disturbance, dependency, or pain. Epicurus warned against overindulgence, but he did not advocate total abstinence. Rather, he encouraged wise choices about when and how to enjoy pleasures, including wine. For Epicureans, occasional intoxication might be permissible—even desirable—if it enhanced fellowship or relaxation without disrupting one’s peace of mind.59

Later Epicurean thinkers, like the Roman poet Lucretius, echoed this position. In De Rerum Natura, Lucretius describes the human tendency to seek out pleasure and escape pain, noting the appeal of wine and other forms of sensual enjoyment.60 However, he also warns that when taken to excess, these pleasures turn into sources of suffering. Intoxication, like superstition or fear of death, is portrayed as a misguided response to human vulnerability. For the Epicureans, then, the problem was not wine itself, but the psychological weakness that led people to use it in excess. Their solution was not rigid prohibition but philosophical education: by teaching people to pursue sustainable, rational pleasures, Epicureanism offered a way to enjoy life without falling into the traps of addiction or compulsion. In this way, the school maintained a balanced view that contrasted with the stricter Stoic denunciations.

Despite their differences, both Stoicism and Epicureanism viewed unrestrained intoxication as incompatible with human flourishing. The Stoics rejected it outright as a surrender to passion, a forfeiture of reason, and a path to moral corruption. The Epicureans, while more tolerant, still regarded it with caution, as a pleasure easily misused and ultimately detrimental if pursued without restraint.61 Both schools saw the habitual need for intoxication as a sign of internal disorder—whether it be irrational attachment or mistaken calculations about what brings happiness. What separates them is not their recognition of the dangers of excessive drinking or drug use, but their philosophical responses: the Stoics prescribe discipline and indifference, while the Epicureans promote selective enjoyment rooted in philosophical clarity. These ancient perspectives continue to offer valuable insights into the moral dimensions of intoxication, highlighting the interplay between ethics, psychology, and the pursuit of a well-ordered life.

Social Perceptions and Consequences of Addiction

Greece

In ancient Greek society, addiction—particularly to wine and other intoxicating substances—was viewed not merely as a personal failing but as a social and moral issue with wide-ranging implications for reputation, civic duty, and family honor. Although the concept of “addiction” in a modern clinical sense did not exist, Greeks clearly recognized patterns of compulsive behavior, especially in relation to drinking, that disrupted personal self-control and social norms.62 Public drunkenness was frowned upon, especially among men of the upper classes who were expected to embody moderation (sōphrosynē), a cardinal virtue in Greek moral thought. A man who regularly lost control under the influence of wine could be labeled akratēs—without mastery over himself—and thus unfit for leadership or even respectable civic life.63 This stigmatization extended beyond personal shame, impacting one’s family and social standing in the tightly knit structure of the polis.

Addiction was especially problematic in the context of Athenian democracy, where male citizens were expected to deliberate rationally in public assemblies and serve as jurors or magistrates. A citizen who habitually indulged in drunkenness could be seen as compromising the very integrity of democratic governance.64 While communal drinking was central to male bonding and intellectual discourse—as seen in the structured environment of the symposium—there was a clear distinction between celebratory drinking and habitual excess. Symposium culture, while tolerant of revelry within bounds, also mocked or excluded those who drank beyond acceptable limits. Comic playwrights like Aristophanes often ridiculed the perpetually inebriated as foolish or effeminate, implying that their condition was socially deviant and unmanly.65 Such portrayals reinforced the notion that addiction eroded both individual virtue and communal values.

Among the elite, moderation was not just a private virtue but a political asset. Philosophers such as Xenophon and Plato frequently emphasized the social dangers of intemperance. In Plato’s Laws, excessive drinking is portrayed as a threat to order and moral discipline, and the legislation he outlines recommends age-based restrictions and state supervision of alcohol consumption.66 Addiction or any form of compulsive indulgence was a mark of the disordered soul—an imbalance that had consequences not only for the individual but for the stability of the city-state. Even the practice of public shame or ridicule could serve as an informal method of regulating such behavior. Social norms thus played a strong role in discouraging substance dependency, especially in a society where honor and reputation were integral to one’s identity and civic worth.

The consequences of perceived addiction extended to legal and familial contexts. In Athens, for example, an individual with a reputation for drunkenness or profligacy might be declared atimos, meaning they could lose certain civic rights, including the ability to speak in the Assembly or serve as a juror.67 In family matters, persistent addiction could result in exclusion from inheritance or serve as grounds for divorce, especially when a husband’s behavior endangered the household’s financial stability or moral standing. Greek law did not criminalize intoxication per se, but it did empower families and communities to take protective or punitive action when substance use became disruptive. This suggests that while addiction was not pathologized in the medical sense, it was deeply embedded in legal, social, and moral discourses.

Despite these negative perceptions, it is also important to recognize that ancient Greek society did allow some socially sanctioned outlets for altered states, such as the Dionysian mysteries. These ritual experiences often involved intoxication and ecstatic behavior but were framed within a religious and communal context, thus shielding participants from the stigma that habitual drunkenness or addiction would carry.68 However, the critical distinction lay in intention and frequency: ritual intoxication was episodic and symbolic, while addiction—seen as a persistent failure of self-control—was regarded as both shameful and dangerous. In short, ancient Greek society saw addiction as a degradation of one’s rational nature and a threat to the moral and civic fabric of the polis. The individual who succumbed to it was not only personally diminished but socially marked, often with long-lasting consequences.

Rome

In ancient Rome, addiction—particularly to alcohol and other intoxicating substances—was perceived through a complex lens of morality, social status, and public order. While drinking wine was deeply embedded in Roman social and religious rituals, excessive or habitual intoxication was widely regarded as a moral failing that jeopardized not only individual dignity but also the stability of the family and the state.69 The Romans, much like the Greeks before them, prized temperantia (moderation) as a cardinal virtue. To lose control to wine or drugs was seen as a sign of weakness, lack of self-discipline, and failure to uphold one’s social and civic responsibilities.70 The mos maiorum, the ancestral customs emphasizing restraint and duty, set the cultural tone, and those who became dependent on intoxicants risked damaging their honor (honor) and social standing. Roman authors frequently associated addiction with moral decadence, often linked to the perceived softness and corruption of the late Republic and early Empire.

Among the Roman elite, public reputation was paramount, and addiction posed a direct threat to one’s political and social career. Cicero, for example, harshly criticized excessive drinking as unbecoming of a statesman, associating it with poor judgment and loss of dignity.71 He and other moralists warned that addiction compromised the virtus (manly excellence) required for leadership. Senators and public figures were expected to embody discipline and rationality, and visible drunkenness was considered humiliating and a political liability. Moreover, the Roman legal system sometimes reflected these concerns: habitual drunkenness could be cited as evidence of incapacity or negligence, affecting one’s eligibility for public office or legal protections.72 The stigma of addiction extended beyond the individual, often impacting family honor and marriage prospects, reflecting the Roman emphasis on familia as the foundation of social order.

At the level of everyday life, Roman attitudes toward addiction were ambivalent. While wine was a staple of daily consumption and central to conviviality, excessive drinking was mocked in popular culture and satirized in literature. Writers such as Juvenal and Martial depicted the habitual drunkard as a figure of ridicule and contempt, whose behavior brought shame upon himself and his household.73 Such depictions underscored the social isolation and loss of respect that accompanied addiction. Furthermore, addiction was often linked to the lower classes and slaves, reinforcing social hierarchies and the notion that self-control was a mark of elite status.74 Yet addiction was not only a matter of class; elite Romans also faced challenges from luxury and excess, which sometimes led to public scandals over opulent banquets and the reckless consumption of wine and other substances.

Roman religion and philosophy also played roles in shaping social perceptions of addiction. Stoic philosophers, influential in Roman intellectual circles, condemned excessive indulgence as a failure of reason and an obstacle to living in accordance with nature.75 Meanwhile, traditional religious festivals often involved ritualized drinking and ecstatic behavior, which were socially sanctioned and temporarily suspended normal social rules.76 However, these ritual intoxications were carefully circumscribed and distinct from the chronic loss of control associated with addiction. The tension between controlled indulgence and dangerous excess reflected broader anxieties about maintaining order within both the individual and the state. The Romans understood addiction not only as a personal vice but as a potential threat to societal harmony.

The consequences of addiction in Roman society were therefore significant and multifaceted. Socially, the addicted individual risked exclusion from elite circles, loss of familial respect, and diminished marriage prospects. Politically, addiction could end careers and damage reputations critical for public life. Legally, intoxication was sometimes used to challenge an individual’s capacity or credibility, though outright criminal penalties for addiction per se were rare.77 At the same time, cultural ambivalence remained, as some forms of intoxication were celebrated or tolerated in specific contexts, particularly in religious or festival settings. Ultimately, Roman social perceptions of addiction combined moral judgment, social control, and practical concerns about public order—attitudes that reveal the tension between indulgence and restraint at the heart of Roman cultural identity.

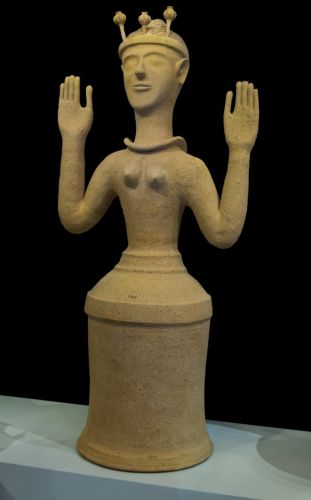

Ritual, Religion, and Intoxication

In both ancient Greece and Rome, intoxication was deeply intertwined with religious ritual and spiritual experience, serving as a means to transcend ordinary consciousness and connect with the divine. The god Dionysus (Bacchus in Roman tradition), as the deity of wine, fertility, and ecstatic frenzy, embodied this sacred intoxication.78 In Greece, Dionysian rites often involved communal drinking, music, dance, and ecstatic states, which were believed to break down the boundaries between the mortal and divine. These rites, particularly the Dionysia festivals, functioned as socially sanctioned occasions where intoxication was not only tolerated but celebrated as a mode of divine possession or inspiration.79 The ritual use of wine in these contexts symbolized the release of inhibitions and the temporary suspension of social norms, allowing participants to access deeper spiritual truths and communal solidarity.

Roman religion inherited and adapted many of these Dionysian elements, though with its own emphasis on order and propriety. The Bacchanalia, the Roman mystery cult of Bacchus, became notorious in the late Republic for alleged excesses of intoxication and moral disorder, which led to a famous Senate crackdown in 186 BCE.80 This repression reflected broader anxieties about the disruptive potential of ritual intoxication when it spilled beyond controlled religious contexts into social and political instability. Nonetheless, the religious use of intoxicants in Rome was widespread and varied, from libations poured to gods to ceremonial feasting, underscoring the sacralized role of alcohol in connecting humans with divine forces.81 Intoxication was thus a liminal state, ritually contained and framed to serve religious meaning rather than personal pleasure alone.

The transformative power attributed to intoxication in these ancient religions was not limited to wine alone. Other substances, such as psychoactive herbs and narcotics, were sometimes incorporated into mystery cults and oracular practices to induce altered states.82 For example, the Eleusinian Mysteries, central to Greek religious life, involved a secretive ritual use of a psychoactive potion (kykeon), believed to facilitate visions and mystical union with Demeter and Persephone.83 While details remain speculative, the presence of such substances points to a broader cultural recognition of intoxication as a tool for spiritual insight. Similarly, in Roman and Greek medical and religious texts, herbal remedies with psychoactive properties were sometimes prescribed or employed in healing rituals, blurring the lines between medicine, religion, and altered states of consciousness.84

Despite these sanctioned religious uses, intoxication remained a double-edged sword, carrying risks of social disorder and moral decay if misused. Philosophical critiques from Stoics and others often warned that the divine ecstasy granted by ritual intoxication should never become habitual drunkenness, which they saw as enslaving the soul rather than liberating it.85 In the public sphere, ritual intoxication was expected to remain within ceremonial bounds, reflecting the delicate balance between order and chaos central to Greco-Roman religious thought. This tension is reflected in literature and law, where excessive indulgence was castigated but ritual use remained respected. Thus, intoxication was both a sacred tool and a potential threat, its value dependent on context, intention, and moderation.

Ritual and religion shaped ancient Greek and Roman attitudes toward intoxication by sacralizing altered states as pathways to divine communion and spiritual renewal. Intoxication in these cultures was carefully ritualized, framed within religious festivals, mysteries, and ceremonies to ensure it served collective and sacred purposes rather than individual excess. The cults of Dionysus/Bacchus exemplify the paradox of intoxication as both ecstatic liberation and social hazard. By integrating intoxicants into religious practice, ancient Greeks and Romans affirmed the human desire to transcend ordinary experience while maintaining vigilance against the disruptive potential of unrestrained indulgence. These attitudes highlight the complex cultural role intoxication played in negotiating the boundaries between the human and the divine, order and chaos.

Conclusion

Substance abuse and addiction in ancient Greece and Rome were multifaceted phenomena that touched upon medicine, philosophy, religion, and daily life. Although lacking a modern clinical framework, these civilizations exhibited a keen awareness of the dangers posed by compulsive indulgence. Philosophers warned against the moral corruption of the soul, physicians documented habituation and its physical consequences, and dramatists satirized those who lost themselves to drink or drugs.

The ancients understood, perhaps better than is often assumed, that the pursuit of pleasure—when unchecked—could become a trap. Their writings serve not only as historical records but as enduring reflections on the human struggle with self-control, moderation, and meaning. In studying their attitudes toward substance use, we gain valuable insight into the timeless nature of addiction and the perennial human desire to escape, transcend, or transform the self.

Appendix

Endnotes

- James Davidson, Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 45.

- Nicholas Purcell, “Wine and Wealth in Ancient Italy,” Journal of Roman Studies 75 (1985): 2.

- Seneca, Letters on Ethics: To Lucilius, trans. Margaret Graver and A. A. Long (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 113.

- Galen, On the Properties of Foodstuffs, trans. Owen Powell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 73.

- Plato, Laws, trans. Trevor J. Saunders (London: Penguin Books, 1970), 244.

- Sarah B. Pomeroy, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity (New York: Schocken Books, 1995), 74.

- Suzanne Dixon, Reading Roman Women: Sources, Genres and Real Life (London: Duckworth, 2001), 88.

- Walter Burkert, Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, trans. John Raffan (Oxford: Blackwell, 1985), 285.

- Livy, History of Rome, Book 39, trans. B. O. Foster (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1939), 39.8–18.

- Michael A. Rinella, Pharmakon: Plato, Drug Culture, and Identity in Ancient Athens (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2010), 15.

- John Scarborough, “Drugs and Medicines in the Roman World,” Expedition 21, no. 3 (1979): 35.

- Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, trans. Lily Y. Beck (Hildesheim: Olms-Weidmann, 2005), 2.132.

- Galen, On the Affected Parts, trans. Rudolph Siegel (Basel: Karger, 1976), 81.

- Heinrich von Staden, Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 408.

- Plato, Phaedo, trans. G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1977), 83c–84a.

- Juvenal, Satires, trans. Susanna Morton Braund (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), 6.290–310.

- David Hill and John Wilkes, “Opium and Poppies in the Roman Empire,” Antiquity 61, no. 231 (1987): 62–65.

- Galen, Method of Medicine, trans. Ian Johnston and G. H. R. Horsley (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 10.15.

- Herodotus, Histories, 4.73–75, trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 292.

- Galen, On the Properties of Foodstuffs, 240.

- Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 3.165.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 24.102, trans. John Bostock and H.T. Riley (London: Taylor and Francis, 1855).

- Galen, On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body, trans. Margaret Tallmadge May (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968), 640.

- Hans Dieter Betz, ed., The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 118–119.

- Sabina Strömqvist, “Cannabis Use in Antiquity: The Archaeological Evidence,” Ancient Near Eastern Studies 42 (2005): 187–202.

- Galen, On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato, trans. Phillip De Lacy (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1978), 204.

- Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 4.76-78.

- Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants, trans. Arthur Hort (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1916), 9.8.3.

- Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 4.69.

- Galen, On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato, 219.

- Brian C. Muraresku, The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020), 117–122.

- Carl A.P. Ruck, Blaise Daniel Staples, and Clark Heinrich. The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries (Berkeley: Hermetic Press, 2008), 65–70.

- John Scarborough, “Pharmacology and Toxicology in the Middle Ages.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 52, no. 1 (1978): 40–58.

- Galen, On Theriac to Piso, trans. Robert Montraville Green (Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1956), 28–29.

- Plato, Phaedo, 81b-d.

- Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, trans. Richard M. Gummere (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1917), Letter 83.

- Hippocrates, Airs, Waters, Places, trans. W.H.S. Jones (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1923), 1.

- Galen, On the Temperaments, trans. Philip De Lacy (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1976), 32.

- Hippocrates, On Regimen, in Hippocratic Writings, trans. J. Chadwick and W.N. Mann (London: Penguin, 1978), 218–221.

- Galen, On the Causes of Symptoms, in Galen: Selected Works, trans. P.N. Singer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 265–267.

- Celsus, De Medicina, trans. W.G. Spencer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935), 1.2.3.

- Galen, On Antidotes, trans. Robert Montraville Green (Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1955), 1.12.

- Galen, On the Properties of Foodstuffs, 78-80.

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terence Irwin (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1985), Book VII.

- Plato, Symposium, trans. Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989), 174a–178d.

- Ibid., 220a–223b.

- Ibid., 209e–212a.

- Ibid., 210a–211d.

- Plato, Laws, II.666a-673c.

- Ibid., II.671e–672d.

- Plato, Symposium, 220a–221d.

- Ibid., 215e–218d.

- Plato, Phaedrus, trans. Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1995), 244a–245c.

- Seneca, Moral Letters to Lucilius, Letter 83.

- Ibid., Letter 122.

- Epictetus, Discourses, trans. Robert Dobbin (London: Penguin Classics, 2008), I.18.

- Ibid., II.23.

- Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus, in The Art of Happiness, trans. George K. Strodach (New York: Penguin, 2012), 131–134.

- Ibid., 135.

- Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, trans. Martin Ferguson Smith (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2001), Book III, lines 830–842.

- A.A. Long, Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 197–204.

- Robin Lane Fox, The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 193–194.

- Michel Foucault, The Use of Pleasure: Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage, 1990), 87–88.

- Josiah Ober, Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 216–217.

- Aristophanes, Wasps, trans. Jeffrey Henderson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), lines 1290–1310.

- Plato, Laws, II.666b-673a.

- David Cohen, Law, Violence, and Community in Classical Athens (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 94–96.

- Walter Burkert, Greek Religion, 285-288.

- Ramsey MacMullen, Drinking in Ancient Rome: A Social History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 45–47.

- Ibid., 52–55.

- Cicero, De Officiis, in Cicero: On Duties, trans. Walter Miller (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913), 1.32–33.

- Fergus Millar, The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998), 102–104.

- Juvenal, Satires, Satire 3.12–20; Martial, Epigrams, trans. D. R. Shackleton Bailey (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), Book 5.

- MacMullen, Drinking in Ancient Rome, 60–62.

- Seneca, Moral Letters to Lucilius, Letter 83; Epictetus, Discourses, II.23.

- Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price, Religions of Rome (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 221–223.

- MacMullen, Drinking in Ancient Rome, 67–69.

- Burkert, Greek Religion, 255-258.

- Henri Jeanmaire, Dionysus: Myth and Cult, trans. Bernard Miall (New York: Dorset Press, 1986), 123–130.

- Beard, North, Price, Religions of Rome, 231-235.

- MacMullen, Drinking in Ancient Rome, 71-75.

- Albert Hofmann, LSD: My Problem Child, trans. Hanscarl Leuner (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 45–47.

- M. C. Algra, The Alleged Use of Psychedelic Drugs in the Eleusinian Mysteries, in The Ancient Mystery Cults (Leiden: Brill, 1996), 158–165.

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (London: Routledge, 2004), 190–192.

- Seneca, Moral Letters to Lucilius, II.23.

Bibliography

- Algra, M. C. The Alleged Use of Psychedelic Drugs in the Eleusinian Mysteries. In The Ancient Mystery Cults. Leiden: Brill, 1996.

- Aristophanes. Wasps. Translated by Jeffrey Henderson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Terence Irwin. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1985.

- Beard, Mary. Religions of Rome. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Betz, Hans Dieter, ed. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Translated by John Raffan. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985.

- Celsus. De Medicina. Translated by W.G. Spencer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935.

- Cicero. On Duties. Translated by Walter Miller. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1913.

- Cohen, David. Law, Violence, and Community in Classical Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Davidson, James. Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

- Dioscorides. De Materia Medica. Translated by Lily Y. Beck. Hildesheim: Olms-Weidmann, 2005.

- Dixon, Suzanne. Reading Roman Women: Sources, Genres and Real Life. London: Duckworth, 2001.

- Epictetus. Discourses. Translated by Robert Dobbin. London: Penguin Classics, 2008.

- Epicurus. The Art of Happiness. Translated by George K. Strodach. New York: Penguin, 2012.

- Foucault, Michel. The Use of Pleasure: Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage, 1990.

- Fox, Robin Lane. The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

- Galen. Method of Medicine. Translated by Ian Johnston and G. H. R. Horsley. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Galen. On the Affected Parts. Translated by Rudolph Siegel. Basel: Karger, 1976.

- Galen. On Antidotes. Translated by Robert Montraville Green. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1955.

- Galen. On the Causes of Symptoms. In Galen: Selected Works. Translated by P.N. Singer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Galen. On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato. Translated by Phillip De Lacy. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1978.

- Galen. On the Properties of Foodstuffs. Translated by Owen Powell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Galen. On the Temperaments. Translated by Philip De Lacy. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1976.

- Galen. On Theriac to Piso. Translated by Robert Montraville Green. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1956.

- Galen. On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body. Translated by Margaret Tallmadge May. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968.

- Herodotus. Histories. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

- Hill, David, and John Wilkes. “Opium and Poppies in the Roman Empire.” Antiquity 61, no. 231 (1987): 62–65.

- Hippocrates. Airs, Waters, Places. Translated by W.H.S. Jones. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1923.

- Hippocrates. On Regimen. In Hippocratic Writings. Translated by J. Chadwick and W.N. Mann. London: Penguin, 1978.

- Hofmann, Albert. LSD: My Problem Child. Translated by Hanscarl Leuner. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

- Jeanmaire, Henri. Dionysus: Myth and Cult. Translated by Bernard Miall. New York: Dorset Press, 1986.

- Juvenal. Satires. Translated by Susanna Morton Braund. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Livy. History of Rome, Book 39. Translated by B. O. Foster. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1939.

- Long, A.A. Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

- Lucretius. On the Nature of Things. Translated by Martin Ferguson Smith. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2001.

- MacMullen, Ramsey. Drinking in Ancient Rome: A Social History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Martial. Epigrams. Translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Millar, Fergus. The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- Muraresku, Brian C. The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020.

- Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Plato. Laws. Translated by Trevor J. Saunders. London: Penguin Books, 1970.

- Plato. Phaedo. Translated by G.M.A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1977.

- Plato. Phaedrus. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1995.

- Plato. Symposium. Translated by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1989.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Translated by John Bostock and H.T. Riley. London: Taylor and Francis, 1855.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1995.

- Purcell, Nicholas. “Wine and Wealth in Ancient Italy.” Journal of Roman Studies 75 (1985): 1–19.

- Rinella, Michael A. Pharmakon: Plato, Drug Culture, and Identity in Ancient Athens. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2010.

- Ruck, Carl A.P., Blaise Daniel Staples, and Clark Heinrich. The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries. Berkeley: Hermetic Press, 2008.

- Scarborough, John. “Drugs and Medicines in the Roman World.” Expedition 21, no. 3 (1979): 33–40.

- Scarborough, John. “Pharmacology and Toxicology in the Middle Ages.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 52, no. 1 (1978): 40–58.

- Seneca. Letters on Ethics: To Lucilius. Translated by Margaret Graver and A. A. Long. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Seneca. Moral Letters to Lucilius. Translated by Richard M. Gummere. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1917.

- Strömqvist, Sabina. “Cannabis Use in Antiquity: The Archaeological Evidence.” Ancient Near Eastern Studies 42 (2005): 187–202.

- Theophrastus. Enquiry into Plants. Translated by Arthur Hort. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1916.

- von Staden, Heinrich. Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.