Laudanum’s history is one of contradiction.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Laudanum—an alcoholic tincture of opium—has left a complex legacy in the history of medicine. Celebrated for its analgesic and sedative properties, yet feared for its addictive potential, laudanum epitomizes the dual-edged nature of many pharmacological breakthroughs. From the Enlightenment era of the 18th century, through the height of Victorian medical culture in the 19th century, and into the regulatory shifts of the 20th century, laudanum’s journey mirrors the broader story of how societies grapple with the promise and peril of powerful drugs. This essay explores laudanum’s evolution as both medicine and menace, tracing how it was prescribed, who used it, the cultural implications of its widespread availability, and the growing recognition of its addictive dangers.

The Origins and Early Medical Use of Laudanum

Composition and Preparation

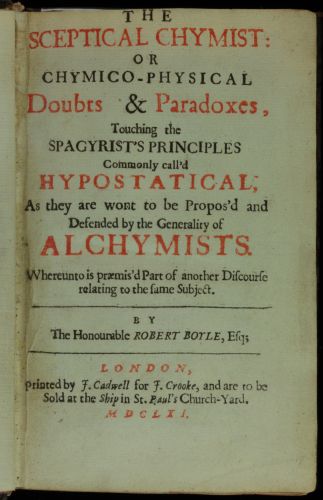

The history of laudanum begins in the 16th century with the work of the Swiss-German alchemist and physician Paracelsus (1493–1541), who introduced a new opium-based elixir he called laudanum. Paracelsus’ formulation, though different from later iterations, marked the beginning of a long pharmacological tradition. His original mixture was not simply a tincture of opium; it combined opium with other botanical and mineral ingredients, suspended in alcohol or sometimes wine, and often included substances like crushed pearls, musk, or amber. He considered it a universal remedy, or arcana, and touted its ability to alleviate pain and cure various diseases. Paracelsus’s emphasis on chemical combinations and dosage control was revolutionary for the period, as it challenged the dominant Galenic humoral theories of medicine and helped lay the foundations for iatrochemistry.1

Throughout the later 16th and early 17th centuries, laudanum remained a compound of complex and often mysterious ingredients. Its precise composition varied depending on the practitioner, but it typically included powdered opium, distilled alcohol (often brandy or fortified wine), and an array of other herbs and animal-based elements. One prominent variation, for example, included saffron, cinnamon, and clove, designed to improve taste and add warming, stimulating properties in accordance with contemporary medical beliefs. The pharmacopoeias of the period seldom provided standardized recipes, and physicians or apothecaries often guarded their specific formulations as proprietary secrets. Laudanum thus remained as much an art as a science, situated in a liminal space between empirical pharmacology and alchemical tradition.2

By the 17th century, however, the preparation of laudanum began to move toward greater uniformity and reliability, especially with the work of Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689), a renowned English physician often called the “English Hippocrates.” Sydenham sought to strip laudanum of its more arcane elements and establish a practical, reproducible formulation based on clinical observation. His version, known as “Sydenham’s Laudanum,” consisted of opium dissolved in sherry wine, with the addition of saffron, cloves, and cinnamon. This simplified yet potent recipe was easier to manufacture and became widely adopted across Europe. Sydenham’s influence helped shift laudanum from a mystical concoction into a mainstream medical preparation, earning it a place in apothecaries’ inventories throughout the Western world.3

The transition from Paracelsian secrecy to Sydenham’s empiricism reflected broader changes in early modern medicine. As the medical profession gradually moved toward evidence-based practice and greater standardization, the need for reproducible formulas became more urgent. The increased use of printed pharmacopoeias and formularies facilitated the spread of standardized laudanum recipes, albeit with slight regional and institutional variations. Apothecaries, licensed and increasingly regulated by guilds or royal charters, began producing laudanum in more consistent batches. The shift in laudanum’s preparation thus mirrored the rise of professionalized medicine and the slow decline of mystical or astrological frameworks in favor of more rational, secular therapeutic models.4

Despite these advancements, the basic pharmacological mechanism of laudanum—its active opium alkaloids—remained poorly understood. While practitioners recognized its remarkable analgesic and sedative effects, the physiological basis for these effects was unknown, and dosing remained imprecise and often dangerous. Early laudanum mixtures varied significantly in strength due to inconsistent opium quality and extraction methods. As a result, accidental overdose was a constant risk, especially when laudanum was compounded by untrained individuals or consumed by laypeople without medical guidance. Nonetheless, laudanum’s powerful efficacy ensured its enduring appeal, setting the stage for its ubiquitous presence in the medicine cabinets of the 18th and 19th centuries.5

Widespread Medical Use in the 18th Century

In the 18th century, laudanum became one of the most commonly prescribed and relied-upon medicines across Europe and its colonies. With its origins in the previous century firmly established through the work of Thomas Sydenham, laudanum emerged as a staple remedy in both professional and domestic medical practice. Physicians prescribed it for a vast range of ailments, including toothaches, fevers, gout, dysentery, menstrual cramps, consumption (tuberculosis), and various forms of “nervous disorders.” Its effectiveness at dulling pain and inducing sleep made it indispensable in an era largely devoid of anesthesia or effective antiseptics. Apothecaries and physicians alike lauded its versatility and viewed it as a general panacea for both physical and emotional maladies, often referring to it simply as “the tincture” in clinical notes and recipes.6

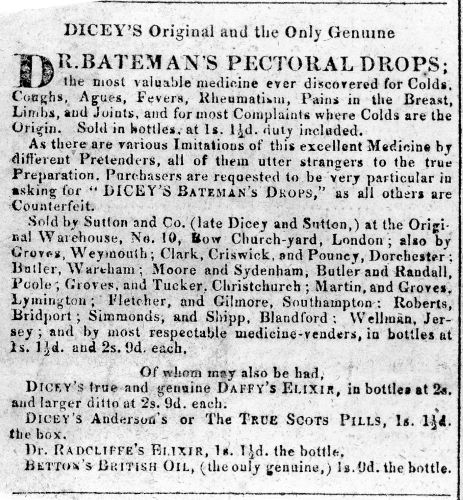

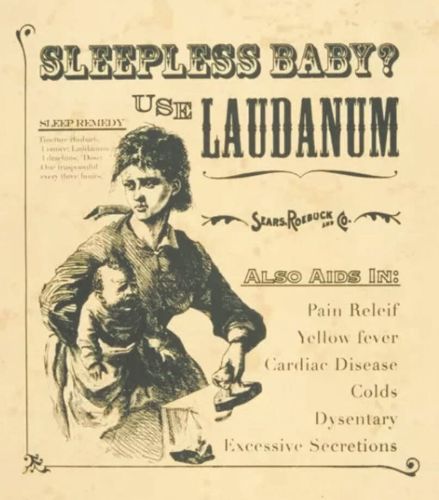

This period witnessed a significant expansion in the accessibility and popularity of laudanum beyond elite medical circles. Inexpensive and available without prescription, it became a fixture not only in apothecaries’ shops but also in household medicine chests. Middle- and upper-class families kept it on hand as a go-to remedy for everyday illnesses, from colic in children to insomnia in adults. Commercial mixtures containing laudanum, such as “Daffy’s Elixir” and “Bateman’s Pectoral Drops,” were advertised in newspapers and broadsheets, often accompanied by exaggerated testimonials of miraculous recoveries. The 18th-century public—accustomed to treating health at home before resorting to doctors—eagerly embraced these opiate-laced remedies as part of the growing culture of self-medication.7

Medical theories of the 18th century further reinforced the use of laudanum as a therapeutic agent. Drawing on both Galenic and newer iatrochemical principles, many physicians saw laudanum not only as a sedative but also as a means to restore bodily balance and relieve internal inflammation. Pain, still poorly understood in scientific terms, was often interpreted as a manifestation of imbalance or congestion. By dulling sensations and slowing bodily functions, laudanum was thought to “cool” or “calm” excessive bodily activity. It was commonly prescribed in febrile illnesses to prevent the perceived dangers of overexertion or overstimulation of the nerves. This broad theoretical flexibility allowed laudanum to be used for almost any diagnosis, making it a universal component of 18th-century pharmacology.8

Despite its widespread use, little attention was paid during this period to the risk of dependence or overdose. While some physicians noted a diminishing effect with repeated use, the notion of drug habituation was poorly understood and rarely discussed in public or professional forums. Instead, persistent use was often viewed as a sign of the severity of the patient’s illness rather than a side effect of the medicine itself. Consequently, many patients—especially those with chronic illnesses—became long-term users of laudanum, often without realizing that their symptoms were being exacerbated by dependence. Children and infants were particularly vulnerable, as opiate-laced remedies were frequently administered for teething pain or to keep infants quiet—a practice that led to numerous cases of accidental poisoning and death, although these were rarely attributed to laudanum at the time.9

The widespread use of laudanum also reflected and reinforced emerging cultural values surrounding health and modernity. As Enlightenment ideals of rationality and scientific progress gained influence, the use of chemical medicines like laudanum came to symbolize medical advancement over traditional herbal or folkloric remedies. Physicians took pride in their ability to prescribe potent, fast-acting compounds, while patients viewed such medicines as signs of proper, “civilized” care. Laudanum became not merely a medical tool but a cultural artifact—an emblem of progress and trust in human mastery over the body’s mysteries. This perception contributed to the drug’s continued dominance in European and colonial medicine well into the 19th century, despite mounting evidence of its dangers.10

The 19th Century: Peak Popularity and the Shadows of Addiction

The Golden Age of Laudanum Use

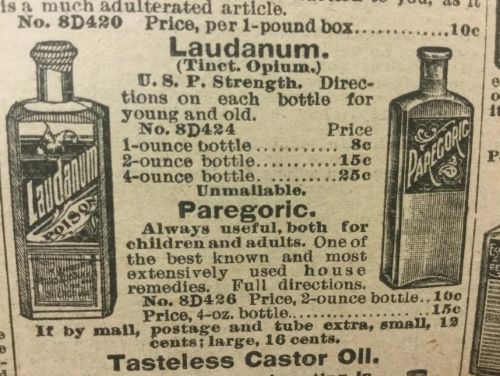

The 19th century marked the zenith of laudanum’s cultural and medical prominence, often referred to as its “Golden Age.” By this period, laudanum was not merely a medical solution but an integral part of everyday life in Britain, Europe, and North America. It was widely available, cheap, and entirely legal, often sold over the counter by apothecaries and general stores. Containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight, laudanum was far more potent than many of today’s pharmaceutical painkillers. It was sold under various names and formulas—some more diluted, others marketed as tonics, elixirs, or pectoral drops. The public largely viewed it not as a dangerous drug but as a reliable and sophisticated medical tool, reflecting confidence in scientific advancement and pharmacological progress.11

During this era, laudanum became deeply embedded in Victorian domestic medicine. It was found in nearly every household, used routinely to treat colds, diarrhea, headaches, melancholia, and female “hysteria.” It was particularly associated with women’s health, prescribed liberally for menstrual pain, post-partum depression, and the vague but all-encompassing diagnosis of “nervous exhaustion.” While physicians often recommended it, many people self-medicated, guided by popular manuals and advertisements. Children, too, were regularly dosed with laudanum to calm teething or crying—formulas like “Godfrey’s Cordial” and “Mother’s Friend” were essentially opium-based sedatives designed for infants. These practices led to widespread physiological dependence across all social classes, even as the addictive potential of laudanum remained largely unacknowledged or misunderstood.12

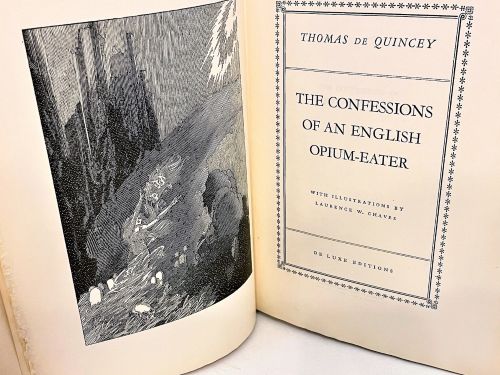

Laudanum’s appeal extended beyond medicine into the realms of art and literature, where it developed an almost mythic status. Many prominent literary and intellectual figures of the 19th century were users—some addicted—including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Thomas De Quincey, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821) immortalized laudanum in public imagination, portraying it as both a tormenting addiction and a portal to sublime, visionary experience. Coleridge, whose opium use likely influenced poems such as Kubla Khan, wrestled with addiction for decades. These cultural narratives contributed to a romanticized image of laudanum as the drug of tortured genius—an elixir capable of unlocking artistic depths and philosophical insight, despite its ruinous consequences. At the same time, such depictions obscured the broader, less glamorous social realities of widespread dependency.13

Medical professionals, meanwhile, continued to embrace laudanum for its practical utility. It was particularly invaluable before the widespread availability of anesthesia. Surgeons often administered laudanum before or after procedures to dull pain or reduce shock. It was also used to treat infectious diseases such as cholera and dysentery, especially during epidemics, where its constipating effect helped control diarrhea. Physicians remained relatively unconcerned with the potential for addiction, frequently emphasizing the importance of controlling symptoms over long-term consequences. The concept of “morphinism” (later opioid addiction) would not be fully theorized until the latter half of the century, and even then, laudanum retained a privileged status in clinical settings due to its perceived respectability and long-standing history.14

By the end of the 19th century, however, awareness of laudanum’s dangers began to shift public and professional opinion. The proliferation of addiction cases, often among women and children, became difficult to ignore. Medical journals increasingly documented dependency and withdrawal, and reformers called for regulation. The pharmaceutical industry also began developing alternatives to crude opium extracts—isolated alkaloids like morphine and later codeine, administered by hypodermic syringe, which was invented in the 1850s. Although these were initially seen as safer, they often led to similar or worse addiction. Legal changes began to emerge late in the century, culminating in early efforts at drug control, including the UK’s Pharmacy Act of 1868, which restricted laudanum sales to registered pharmacists. Nonetheless, laudanum’s long-standing cultural legitimacy meant it remained widely used, bridging two worlds: one of traditional, open drug use and another of increasing medical and legal scrutiny.15

Literary and Cultural Presence

The 19th century saw laudanum transcend its medical origins to become a potent cultural symbol, embedded in literature, visual arts, and broader societal consciousness. While it remained a staple of household medicine, its dual identity as both remedy and intoxicant captured the imagination of the Romantic and later Victorian sensibilities. Writers, poets, and artists often found in laudanum a means of exploring altered states of consciousness, suffering, and creativity. It came to signify a tension between enlightenment rationalism and the darker, more irrational impulses of the human psyche—a symbolic fulcrum between science and the sublime. Its literary representation often oscillated between that of a divine muse and a destructive daemon.16

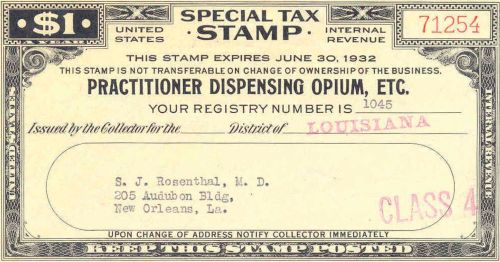

Perhaps the most iconic cultural artifact of laudanum use was Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), a semi-autobiographical narrative that set the tone for how laudanum would be perceived in literary circles for generations. De Quincey described his initial euphoria, visions, and creative invigoration, followed by haunting nightmares, social withdrawal, and profound psychological torment. His ornate prose captured the allure and horror of the drug with almost religious awe, helping establish the romantic archetype of the tortured genius. The book was not only widely read but also widely imitated, becoming a genre-defining work that influenced later depictions of addiction, introspection, and artistic suffering in British literature.17

Other literary figures of the 19th century were also entwined with laudanum, both in life and on the page. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose opium addiction was well-documented, likely composed Kubla Khan and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner under its influence. His writings reflect opium’s surreal and visionary effects, with images of dreamlike landscapes and metaphysical speculation. Similarly, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and George Eliot were known laudanum users, the former for lifelong ailments and the latter for managing chronic pain. While these authors did not necessarily center opium thematically in their work, its presence in their lives colored their creative output and reflected a broader cultural norm among intellectual elites, where opium was seen less as a vice and more as a legitimate tool of mental and physical relief.18

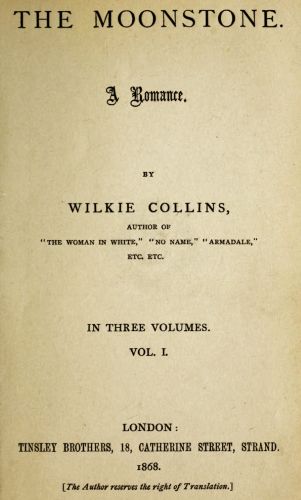

Laudanum’s influence extended into Gothic and sensation fiction, where its ability to alter perception and undermine the boundaries of reason made it a perfect device for narrative intrigue and psychological exploration. Writers like Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens wove opium into their plots to evoke mystery, madness, and decay. In Collins’s The Moonstone (1868), the character Ezra Jennings uses opium to reconstruct a mystery under the influence of altered memory, illustrating contemporary fascination with the subconscious mind. Dickens, in The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), introduces an opium den as a site of moral ambiguity and urban squalor, reflecting the growing anxieties around addiction and social disorder. Such portrayals situated laudanum within the public imagination as both a source of escape and a signifier of psychological and societal collapse.19

Beyond literature, laudanum appeared in theater, visual art, and early popular culture. Victorian melodramas sometimes featured opium-addled characters or highlighted the drug’s role in tragic downfall, mirroring real-world cases of dependency and overdose. Painters like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, created works infused with dreamlike melancholy that mirrored the aesthetic associated with laudanum-induced reverie, although Rossetti’s own rumored use remains debated. More broadly, laudanum became part of Victorian cultural furniture—an object simultaneously domestic and dangerous, banal and bewitching. Its ambiguous position in culture mirrored contemporary concerns about modernity, health, morality, and the limits of human control. By century’s end, laudanum was no longer just a drug but a metaphor: for lost innocence, for artistic suffering, and for the seductive dangers of progress itself.20

The Gendered Use of Laudanum

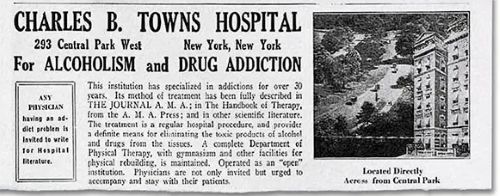

The 19th century’s widespread use of laudanum was not only a medical phenomenon but a profoundly gendered one. Women, particularly middle- and upper-class Victorian women, were among the most frequent users of laudanum. The cultural ideals of femininity—delicacy, emotional sensitivity, passivity—combined with patriarchal medical practices to construct women as especially suited to opiate treatment. Physicians routinely prescribed laudanum to women for a wide range of ailments, many of which were psychosomatic or ill-defined, such as “hysteria,” “nervous disorders,” and “melancholia.” These diagnostic labels functioned as coded expressions of societal discomfort with women’s emotions, intellect, and resistance to domestic roles. Rather than addressing the structural or psychological sources of distress, doctors turned to laudanum as a chemical solution to keep women docile and compliant within restrictive gender norms.21

Men, while also frequent users of opiates, tended to consume laudanum in contexts that emphasized physical labor, battlefield injuries, or philosophical introspection—uses that reinforced masculine identities tied to work, heroism, or intellectual suffering. In contrast, women’s use was portrayed in terms of frailty and dependence. Many women were introduced to laudanum during childbirth or menstrual cycles, periods when their physical suffering was both expected and pathologized. As pain relief, laudanum was effective and fast-acting, yet its long-term use often led to addiction. Physicians were often slow or unwilling to recognize the symptoms of dependency in women, seeing their chronic use of opiates as a natural extension of their supposed emotional instability. The assumption that women were more “prone” to addiction also ignored the ways in which medical authority encouraged and perpetuated their drug dependence.22

Notably, female laudanum addicts were rarely criminalized in the same way as their male counterparts or as later morphine users would be. This was largely because addiction among women was seen as a private, domestic problem rather than a public threat. The Victorian home, often idealized as a haven of moral virtue, concealed significant levels of substance use, especially among housewives and mothers. Women could obtain laudanum easily from apothecaries without a prescription, and its presence in household remedies made its administration nearly invisible. Mothers dosed not only themselves but also their children, leading to widespread and generational exposure to opiates. The invisibility of this dependency within the domestic sphere reflects both the privatization of women’s suffering and the moral blind spots of Victorian society regarding pharmaceutical control.23

The association of laudanum with women also filtered into literature and art, where it carried both erotic and tragic connotations. The figure of the pale, opium-addled woman became a recurring motif in poetry and fiction, often symbolizing purity corrupted, intellect repressed, or desire suppressed. Writers such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning, herself a lifelong user of laudanum for chronic illness, drew from personal experience to portray female suffering in nuanced ways, while others, like Thomas Hardy, depicted laudanum addiction as a tragic consequence of women’s social entrapment. The “fallen woman,” a staple of Victorian literature, was often a laudanum user, her drug use a metaphor for moral decline as well as emotional desperation. These portrayals underscored the perception that women’s use of laudanum was both a symptom of societal constraints and a rebellion against them.24

Toward the end of the century, concerns over female laudanum addiction began to shift from passive tolerance to moral panic. This shift was partly driven by growing public awareness of addiction as a medical condition rather than merely a weakness of character. As medical journals and reformers documented the prevalence of opiate dependency, particularly among respectable women, calls for regulation intensified. Yet even in these reformist narratives, gendered assumptions persisted: female addicts were often portrayed as victims in need of rescue, while male addicts were viewed with suspicion or contempt. The framing of laudanum addiction as a gendered crisis thus reinforced the very ideologies that had contributed to its emergence—treating women’s suffering with medication rather than empathy or reform. In this way, laudanum became both a symbol and a tool of 19th-century gender politics, revealing the deep entanglement of medical practice, cultural norms, and patriarchal control.25

The 20th Century: Decline, Regulation, and Residual Use

Growing Awareness and Early Regulation

By the dawn of the 20th century, laudanum—once ubiquitous in households and hospitals—was increasingly viewed through a lens of caution and skepticism. Medical professionals began recognizing that opiate dependence was not merely a moral failing or a rare affliction but a systemic problem exacerbated by the casual prescribing of potent substances like laudanum. As case studies and clinical reports accumulated, physicians and reformers documented the alarming prevalence of addiction among both men and women, especially within the middle and upper classes. The genteel respectability that had previously cloaked laudanum users began to erode, replaced by concern over the public health implications of widespread, poorly monitored opiate use. This changing perception coincided with broader movements in professionalizing medicine and applying more rigorous scientific standards to drug efficacy and safety.26

The early 20th century also marked the birth of regulatory frameworks aimed at curbing the unregulated sale and consumption of opiates. In the United States, the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act was a landmark piece of legislation that required proper labeling of ingredients in medicinal products. Although it did not ban laudanum outright, it forced manufacturers to disclose the presence of opium and its derivatives in over-the-counter remedies. This transparency marked the beginning of public awareness regarding the risks of such substances. Consumers, many of whom had been unaware that their “soothing syrups” or “cough elixirs” contained opiates, were now confronted with the reality of their medication’s addictive potential. The Act represented the first federal effort to bring medical substances under the scrutiny of law, laying the groundwork for future control.27

The next major regulatory milestone came with the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, which effectively criminalized non-medical opiate use and drastically curtailed access to laudanum. Though framed as a tax measure, the law introduced stringent recordkeeping and prescription requirements, essentially making physicians gatekeepers of narcotic distribution. Laudanum, still available by prescription, was now more difficult to obtain, and its cultural status began to shift from a household staple to a dangerous, controlled substance. The act marked a pivotal moment in the medical and legal approach to narcotics: it acknowledged addiction as a serious issue requiring government oversight, but it also initiated a period of criminalization and stigmatization that would have lasting consequences. Medical practitioners were often caught in a bind—balancing the legitimate need for pain relief with the fear of legal scrutiny or contributing to dependency.28

Public discourse around laudanum also changed dramatically during this period. No longer romanticized as the drug of poets and melancholic women, it was increasingly portrayed as a societal ill. Newspapers reported on opium dens, addiction scandals, and medical malpractice involving narcotics, sensationalizing the issue and further eroding the drug’s image. Reformers, often led by temperance activists and women’s groups, framed laudanum and other opiates as threats to family and moral order. These movements helped push for tighter regulations, arguing that the government had a responsibility to protect its citizens from harmful substances. Simultaneously, the American medical establishment began advocating for better education around narcotics in medical schools, promoting standardized treatment protocols, and discouraging indiscriminate prescriptions. These shifts reflected an evolving understanding of addiction not merely as a vice, but as a public health issue requiring coordinated intervention.29

Despite these efforts, laudanum remained in limited medical use well into the mid-20th century, particularly in rural or underregulated areas where access to newer pharmaceuticals was restricted. In some cases, elderly patients who had been prescribed laudanum for decades continued to rely on it, protected by grandfather clauses or physician discretion. However, as newer synthetic opioids like morphine, heroin, and eventually codeine and oxycodone entered the medical market, laudanum was increasingly seen as antiquated. Its dosage unpredictability, alcohol content, and the emergence of safer, more targeted alternatives rendered it obsolete in mainstream pharmacology. By the 1950s, laudanum had all but disappeared from American pharmacies, now remembered more as a relic of Victorian medicine than a legitimate therapeutic option. Yet its legacy endured—both in the cautionary tales of early addiction and in the legal infrastructure built to control drugs in its wake.30

The Medicalization of Addiction

The early 20th century marked a crucial transition in the understanding of addiction, shifting it from a moral failing or social vice to a diagnosable and treatable medical condition. Laudanum, long a staple of household and clinical medicine, was emblematic of this shift. Its fall from grace was not simply due to regulatory intervention, but also to a growing body of medical literature that framed opiate dependence—previously labeled as “habituation”—as a physiological disorder rooted in chemical changes within the brain. This redefinition was pivotal, particularly for physicians and public health officials who now viewed users less as degenerates and more as patients in need of care. While this reconceptualization was not free from moralizing rhetoric, it laid the groundwork for a scientific approach to addiction that continues to shape modern medical practice.31

Laudanum’s role in this process was paradoxical. On the one hand, it became an object of medical scrutiny as doctors began documenting the long-term effects of opiate consumption. On the other hand, it remained a tool in the physician’s arsenal, albeit more cautiously prescribed. As addiction came under the purview of emerging medical specialties—especially psychiatry and pharmacology—laudanum was increasingly used in controlled settings to wean patients off stronger narcotics like morphine and heroin. This therapeutic strategy, known as “substitution treatment,” reflected a new clinical logic: rather than abruptly halting narcotic intake, doctors attempted to manage withdrawal symptoms through more familiar and stable opiates, among which laudanum still had a place. These methods were forerunners to later treatments involving methadone and buprenorphine.32

Medical institutions, particularly in the United States and Europe, began establishing dedicated addiction treatment facilities by the 1920s and 1930s. While these centers rarely focused on laudanum addiction specifically—owing to its declining prevalence—they were directly influenced by decades of unregulated opiate use. Many of the patients admitted had histories with laudanum, particularly older individuals who had been prescribed it before stricter controls were implemented. At the same time, early psychological theories of addiction emerged, blending Freudian ideas of neurosis with biological theories of dependence. Addiction was increasingly seen as a chronic illness requiring long-term treatment, not simply abstinence. The slow institutionalization of addiction medicine created a space for more compassionate, albeit still imperfect, models of care.33

Nevertheless, significant stigma continued to surround addiction, even under the guise of medicalization. Laudanum, which once carried an aura of sophistication and intellectualism—especially in literary and artistic circles—was now associated with frailty, dysfunction, and moral decay. Women, in particular, continued to suffer disproportionately from this stigma. Though medicine acknowledged addiction as a disease, treatments for women were often punitive or patronizing, reinforcing older gendered assumptions about emotional instability. The legacy of laudanum in women’s health—wherein physical pain and mental anguish were chemically pacified rather than treated holistically—remained a cautionary tale in discussions around the overmedication of women throughout the 20th century. These tensions revealed the limitations of early medical approaches, which often treated symptoms without addressing broader social determinants.34

By the mid-20th century, laudanum had largely disappeared from medical practice, replaced by newer, more refined opioids and synthetic drugs. Yet its influence on the discourse around addiction remained profound. The legacy of laudanum highlighted the dangers of easy access, lack of oversight, and the consequences of treating chronic conditions with addictive substances. As public health agencies and medical schools expanded addiction education, laudanum featured prominently as a historical case study in early mismanagement. It served as a reminder of how cultural norms, gender roles, and commercial interests could shape—and distort—medical decision-making. In this sense, the medicalization of addiction did not erase laudanum’s legacy but transformed it into a symbol of medicine’s evolving responsibilities toward its patients, particularly those caught at the intersection of dependency and neglect.35

Residual Cultural Echoes

Although laudanum had largely vanished from pharmacy shelves and respectable medical use by the mid-20th century, its influence lingered in cultural memory and public consciousness. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, laudanum was still invoked in literature, film, and public discourse as a symbol of the Gothic, the melancholic, and the dangerously romantic. The image of the laudanum-addicted poet or fragile woman lingered in the popular imagination, often as a shorthand for emotional or psychological fragility. Works referencing the drug evoked a bygone era when pain was numbed by tinctures and inner torment was chemically silenced. In this way, laudanum became a cultural artifact—no longer consumed in large quantities, but still haunting the collective memory of Western society.36

One of the most notable areas in which laudanum maintained its presence was in literature. Mid-20th-century authors, particularly those influenced by the Romantic and Decadent traditions, often referenced laudanum as a historical nod to artistic suffering or as an emblem of period authenticity. In novels set in the Victorian or Edwardian eras, laudanum served as both a narrative device and a symbol—representing the fine line between genius and madness, medicine and poison. For instance, historical fiction writers such as Jean Rhys and Daphne du Maurier, among others, evoked laudanum to anchor characters in specific emotional states or social conditions. Its presence was rarely neutral; rather, it called forth associations with decline, repression, and emotional escape, rooted in a cultural past that had not yet been entirely discarded.37

The imagery of laudanum also permeated early Hollywood cinema and television, which frequently drew upon 19th-century narratives. In period dramas and thrillers, the bottle of laudanum was a recognizable prop, one that viewers would associate with death, despair, or secret suffering. This reflected a broader trend in which laudanum had become less a real drug and more a cultural motif—like arsenic or absinthe—that evoked particular aesthetic moods. Even as newer synthetic opioids replaced laudanum in real life, the tincture’s place in fictional representations remained surprisingly stable. Its connection to mystery, crime, and feminine affliction reinforced older tropes of hysteria and opiate dependency, often in gendered and classed ways. The character of the laudanum-using woman—usually upper class, emotionally unstable, and cloistered—persisted in visual culture long after actual laudanum use had sharply declined.38

In medicine, too, the shadow of laudanum did not entirely disappear. Older physicians who had practiced in the early 20th century sometimes recalled prescribing laudanum, and their recollections filtered into medical memoirs and training anecdotes. The drug’s legacy was thus preserved as a cautionary tale within medical education, a reminder of the era before robust pharmacological controls and clinical trials. Public health campaigns of the mid-20th century occasionally referenced the laudanum epidemic of the 19th century as a historical antecedent to growing concern over barbiturates and emerging synthetic drugs. As the United States and other countries began grappling with the first signs of prescription drug abuse, laudanum was cited as an early example of how well-intentioned medical substances could give rise to widespread harm if inadequately regulated.39

Laudanum’s cultural afterlife helped shape the language and conceptual framework surrounding addiction and psychoactive substances. Its status as both cure and curse made it a powerful metaphor for broader anxieties about pharmaceutical intervention, the medicalization of mental health, and the thin line between treatment and dependence. Writers, scholars, and reformers often drew upon the laudanum legacy to argue against uncritical faith in modern drug therapies. In this sense, the tincture functioned as a bridge between centuries—a tangible link to older forms of suffering and solace, and a historical mirror in which modern society could view its own ambivalent relationship with medication. Laudanum’s continued presence in cultural texts through the mid-20th century testified to the lasting imprint of a drug that had once been both widely revered and quietly feared.40

Conclusion

Laudanum’s history is one of contradiction: a powerful medicine that alleviated suffering in an age of limited alternatives, yet also a substance that ensnared millions in addiction. From the drawing rooms of Victorian England to the legislative halls of 20th-century reformers, laudanum’s trajectory reflects a broader narrative about the promises and perils of pharmacology. It reminds us that medical progress must be balanced with ethical foresight, scientific understanding, and societal responsibility. The story of laudanum ultimately foreshadows modern debates about opioids, addiction, and the fine line between healing and harm.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Walter Pagel, Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Basel: Karger, 1958), 106–109.

- Jonathan Andrews et al., The History of Bethlem (London: Routledge, 1997), 54–55.

- Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 262–263.

- Harold J. Cook, The Decline of the Old Medical Regime in Stuart London (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1986), 92–95.

- Richard Davenport-Hines, The Pursuit of Oblivion: A Global History of Narcotics (New York: W. W. Norton, 2002), 20–22.

- Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, 312-314.

- Louise Foxcroft, The Making of Addiction: The “Use and Abuse” of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), 9–12.

- Anita Guerrini, Obesity and Depression in the Enlightenment: The Life and Times of George Cheyne (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 95–97.

- Virginia Berridge and Griffith Edwards, Opium and the People: Opiate Use in Nineteenth-Century England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 25–27.

- Mark Jackson, The Age of Stress: Science and the Search for Stability (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 44–46.

- Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, 500-502.

- Berridge and Edwards, Opium and the People, 35-38.

- Alethea Hayter, Opium and the Romantic Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), 10–25.

- Foxcroft, The Making of Addiction, 47-50.

- Martin Booth, Opium: A History (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), 142–145.

- Hayter, Opium and the Romantic Imagination, 3-7.

- Thomas De Quincey, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (London: Taylor and Hessey, 1821), introduction.

- Molly Lefebure, Samuel Taylor Coleridge: A Bondage of Opium (New York: Stein and Day, 1974), 112–116; Virginia Berridge and Griffith Edwards, Opium and the People: Opiate Use in Nineteenth-Century England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 64–66.

- Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone (London: Tinsley Brothers, 1868); Charles Dickens, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (London: Chapman & Hall, 1870).

- Martin Booth, Opium, 155-159.

- Foxcroft, The Making of Addiction, 80-84.

- Berridge and Edwards, Opium and the People, 108-112.

- Judith Leavitt, Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750–1950 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 135–137.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh (London: Chapman and Hall, 1856); Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles (London: James R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Co., 1891).

- Booth, Opium, 170-174.

- David T. Courtwright, Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 66–69.

- Caroline Jean Acker, Creating the American Junkie: Addiction Research in the Classic Era of Narcotic Control (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 32–35.

- David F. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 43–47.

- Jill Jonnes, Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams: A History of America’s Romance with Illegal Drugs (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 58–61.

- Booth, Opium, 188-192.

- Courtwright, Dark Paradise, 98-101.

- Acker, Creating the American Junkie, 49-52.

- Nancy D. Campbell, Discovering Addiction: The Science and Politics of Substance Abuse Research (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007), 65–69.

- Susan Zieger, Inventing the Addict: Drugs, Race, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century British and American Literature (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008), 142–145.

- Booth, Opium, 210-214.

- Roy Porter, Madness: A Brief History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 137–139.

- Catherine Maxwell, The Female Sublime from Milton to Swinburne: Bearing Blindness (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001), 182–186.

- Elizabeth Bronfen, Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992), 224–228.

- Musto, The American Disease, 122-126.

- Zieger, Inventing the Addict, 168-172.

Bibliography

- Acker, Caroline Jean. Creating the American Junkie: Addiction Research in the Classic Era of Narcotic Control. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Andrews, Jonathan, et al. The History of Bethlem. London: Routledge, 1997.

- Barrett Browning, Elizabeth. Aurora Leigh. London: Chapman and Hall, 1856.

- Berridge, Virginia, and Griffith Edwards. Opium and the People: Opiate Use in Nineteenth-Century England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

- Booth, Martin. Opium: A History. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

- Bronfen, Elizabeth. Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992.

- Campbell, Nancy D. Discovering Addiction: The Science and Politics of Substance Abuse Research. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007.

- Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1868.

- Cook, Harold J. The Decline of the Old Medical Regime in Stuart London. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1986.

- Courtwright, David T. Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Davenport-Hines, Richard. The Pursuit of Oblivion: A Global History of Narcotics. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002.

- De Quincey, Thomas. Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. London: Taylor and Hessey, 1821.

- Dickens, Charles. The Mystery of Edwin Drood. London: Chapman & Hall, 1870.

- Foxcroft, Louise. The Making of Addiction: The “Use and Abuse” of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

- Guerrini, Anita. Obesity and Depression in the Enlightenment: The Life and Times of George Cheyne. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

- Hayter, Alethea. Opium and the Romantic Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968.

- Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d’Urbervilles. London: James R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Co., 1891.

- Jackson, Mark. The Age of Stress: Science and the Search for Stability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Jonnes, Jill. Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams: A History of America’s Romance with Illegal Drugs. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- Leavitt, Judith Walzer. Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750–1950. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Lefebure, Molly. Samuel Taylor Coleridge: A Bondage of Opium. New York: Stein and Day, 1974.

- Maxwell, Catherine. The Female Sublime from Milton to Swinburne: Bearing Blindness. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001.

- Musto, David F. The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Pagel, Walter. Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance. Basel: Karger, 1958.

- Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

- Porter, Roy. Madness: A Brief History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Zieger, Susan. Inventing the Addict: Drugs, Race, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century British and American Literature. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.