Precedents set during times of crisis often linger and become tools for oppression.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Donald Trump invoked the Insurrection Act to send military troops to Los Angeles, and our Founders are rolling in their graves. They feared and hotly debated even having a standing army for this very reason. They had lived under the boot of military oppression in the streets and wanted no part of it.

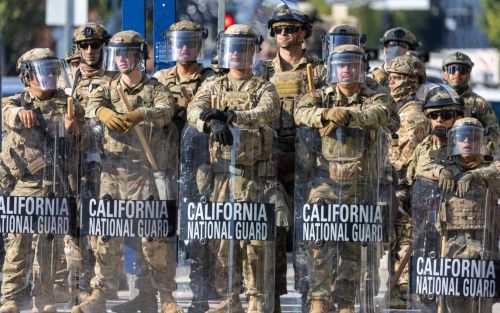

The use of military forces within the borders of the United States has long been a sensitive and contentious issue. When active-duty troops are deployed to American cities such as Los Angeles, it raises serious constitutional and legal questions about the role of the armed forces in civil society. Chief among these concerns is the potential violation of the Posse Comitatus Act—a federal law designed to limit the government’s ability to use military power to enforce domestic laws. The act exists to preserve the fundamental distinction between military and civilian authority, a line that has been blurred in moments of national crisis but is essential to the integrity of a free republic.

In the current climate, where political polarization and civil unrest frequently overlap, the notion of deploying military personnel to control or manage domestic events can seem expedient. But such actions, when taken outside the narrow boundaries allowed by law, do not simply bend legal frameworks—they break them. The deployment of federal troops to a city like Los Angeles without explicit statutory or constitutional authority is a direct violation of the Posse Comitatus Act and threatens to erode the balance of powers upon which American democracy rests.

Understanding the Posse Comitatus Act

The Posse Comitatus Act was enacted in 1878, following the end of Reconstruction. It was a response to the widespread use of federal troops in the South, where the military had been enforcing civil law and overseeing elections. Although these interventions were often necessary to protect the rights of newly freed African Americans, they also stirred fear among many Americans—particularly in former Confederate states—about the unchecked power of the federal government and the potential for military tyranny.

The law, which is codified at 18 U.S. Code § 1385, prohibits the willful use of the Army or Air Force to execute domestic laws except where expressly authorized by the Constitution or by an act of Congress. While the statute does not explicitly mention the Navy or Marine Corps, Department of Defense policy extends the act’s restrictions to those branches as well. The National Guard, when operating under state authority, is exempt from the Posse Comitatus Act, but once federalized, it too falls under its restrictions.

The statute (18 U.S. Code § 1385) reads:

“Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or the Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.”

This legal barrier was established to reinforce a core democratic principle: that military forces should not be used to police civilians. The distinction between soldiers and law enforcement officers is more than functional—it is ideological. Soldiers are trained to combat enemies and win wars, not to de-escalate domestic tensions or protect constitutional rights in a civilian context. When the military is used for law enforcement purposes, it fundamentally alters the relationship between the government and the governed.

The Limits of Military Involvement in Domestic Affairs

There are rare and narrowly defined exceptions under which the federal government can deploy military forces domestically. Chief among these is the Insurrection Act, a set of statutes dating back to the early nineteenth century that grants the president the authority to use troops to suppress insurrection, rebellion, or serious civil disorder. The law allows for federal intervention when requested by a state’s governor, when civil unrest obstructs the execution of federal laws, or when citizens are deprived of their constitutional rights and state governments fail or refuse to act.

Another legal framework exists in the form of the National Emergencies Act, which permits the president to invoke emergency powers under certain circumstances. However, these powers are not open-ended and must align with existing statutory limitations, including those established under the Posse Comitatus Act. Moreover, even in emergency situations, the use of the military to perform traditional law enforcement functions—such as making arrests, conducting searches, or seizing property—is generally prohibited.

There are some support roles the military may provide without violating the law, such as offering technical assistance, intelligence, or equipment to civilian authorities. But once troops begin engaging directly in policing actions—patrolling neighborhoods, enforcing curfews, or confronting protesters—their presence transitions from support to enforcement, crossing into prohibited territory under the law.

Historical Precedents and Warnings

The deployment of military troops to Los Angeles is not without precedent, though each past case has generated significant legal and political controversy. In 1992, following the acquittal of police officers involved in the beating of Rodney King, widespread riots broke out across Los Angeles. President George H. W. Bush invoked the Insurrection Act after a formal request from California Governor Pete Wilson. Under this framework, federal troops were legally deployed to help restore order. While this action technically complied with the law, it reignited national debate about the militarization of domestic response and the fine line between order and occupation.

More recently, in 2020, the Trump administration considered deploying active-duty military units to several U.S. cities, including Los Angeles, to quell protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Although the troops were never actually deployed, the proposal drew swift condemnation from civil rights groups, retired military leaders, and lawmakers. Former Secretary of Defense James Mattis warned publicly that using the military to suppress dissent undermines both public trust and democratic institutions. The situation underscored how even the contemplation of such deployments can stoke fears of authoritarian overreach.

In the absence of an insurrection or formal state request, sending troops to Los Angeles—or any city—represents a clear violation of the Posse Comitatus Act. It circumvents both Congressional authority and state sovereignty, setting a dangerous precedent for future administrations that may be less restrained or more politically motivated.

The Erosion of Civil Liberties and Constitutional Norms

When military troops are used to enforce civilian laws, the potential for abuse is high. Soldiers are not trained in constitutional law, civil rights protections, or community policing. Their tools, tactics, and mindset are oriented toward combat and threat neutralization—not de-escalation or the protection of civil liberties. The presence of armed troops on American streets communicates a shift in the social contract: it signals that the government no longer trusts its citizens and that force, rather than justice or dialogue, is the preferred method of governance.

The risks are even greater for marginalized communities, who have historically faced disproportionate surveillance, violence, and suppression from both military and law enforcement authorities. The deployment of troops can deepen mistrust, fuel unrest, and delegitimize state and local governance.

Moreover, each time the Posse Comitatus Act is ignored or circumvented, it becomes easier to do so again. Legal norms, once broken, are difficult to repair. and become tools for future administrations to exploit. The erosion of the wall between military and civil power does not happen all at once—it occurs in increments, each one rationalized as necessary, until the wall is no longer standing.

Conclusion

The deployment of federal military forces to Los Angeles—unless expressly authorized by law—is a direct violation of the Posse Comitatus Act and a threat to the constitutional balance between military and civilian authority. The act is not an obstacle to order but a safeguard against tyranny. It is rooted in a long-standing American tradition of limiting centralized power and ensuring that those who enforce the law are accountable to the people, not to the chain of command.

At a time when democratic institutions are under strain and public trust in government is fragile, it is more important than ever to uphold the legal and moral boundaries that preserve civil liberty. The military has a noble and necessary role in national defense. That role does not extend to patrolling our streets, silencing dissent, or replacing the responsibilities of civilian law enforcement. Upholding the Posse Comitatus Act is not simply a matter of legality—it is a reaffirmation of the values upon which the United States was founded.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.