The Nile River’s bounty slowly poisoned millions over centuries.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

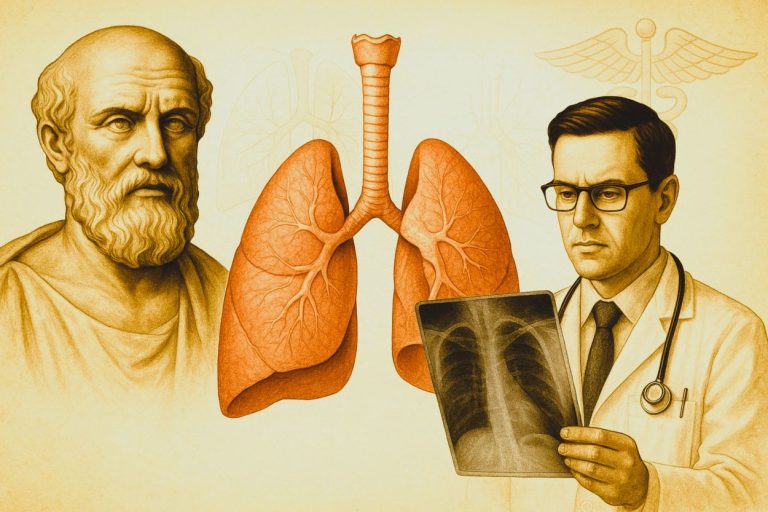

The phrase “Pharaoh’s Curse” evokes images of tombs, mummies, and mysterious deaths—an enduring fixture of popular imagination since the sensationalized opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the 1920s. While the idea of a supernatural curse has long been dismissed, the phrase may have an ironic ring of truth in its evocation of real biological afflictions that plagued ancient Egyptian society. One such affliction, chronic schistosomiasis, was a pervasive and insidious disease that left its mark not only on individual lives but on the broader health and labor systems of the Nile Valley. Schistosomiasis, caused by parasitic blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma, is now recognized through both paleopathological evidence and textual inference as one of the most widespread and devastating diseases of the ancient world. Here we explore the epidemiology, social impact, and symbolic significance of chronic schistosomiasis in ancient Egypt and surrounding regions, arguing that its enduring presence constitutes a kind of biological “curse” borne silently by the people of the Pharaohs.

The Life Cycle of a Curse

Schistosomiasis is caused by several species of trematode flatworms that thrive in freshwater environments. The disease is transmitted when larval parasites, known as cercariae, penetrate human skin upon contact with contaminated water. Once inside the body, the larvae mature into adult worms and settle in the venous plexuses of the urinary bladder or intestines, depending on the species. The adult worms release eggs, some of which are excreted, while others become lodged in tissues, where they trigger chronic immune responses, leading to granulomas, fibrosis, and in some cases, bladder or liver cancer.1

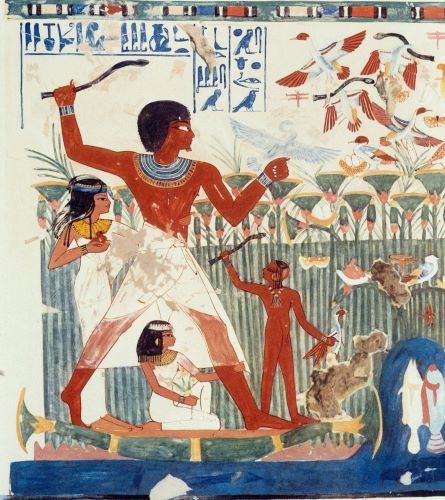

In the context of ancient Egypt, this mode of transmission had lethal ecological synergy. The reliance on the Nile for irrigation, bathing, and washing—especially with the construction of canal systems under the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom—created ideal conditions for transmission. The intermediate host, freshwater snails of the genus Biomphalaria and Bulinus, flourished in stagnant or slow-moving waters.2 Farmers and laborers, often waist-deep in irrigation canals, were particularly vulnerable to infection.

Paleopathological Evidence from the Dead

The primary line of evidence for ancient schistosomiasis lies in paleopathology—the study of disease in ancient remains. In the 1970s, Sir Marc Armand Ruffer, a pioneer in the study of ancient disease, discovered calcified Schistosoma haematobium eggs in the kidneys and bladder tissues of Egyptian mummies dating from 1250 BCE.3 These findings were later confirmed by other researchers using immunological and molecular techniques. In one study, S. haematobium antigens were detected in 4000-year-old tissues using ELISA assays, demonstrating not only infection but chronic exposure over time.4

One particularly telling case is that of a mummy from the early 20th Dynasty (c. 1200 BCE), in which severe bladder pathology and fibrosis were consistent with advanced urinary schistosomiasis.5 This not only confirms the disease’s presence but indicates it reached debilitating or even fatal levels among a segment of the population.

Social and Economic Consequences

The widespread nature of schistosomiasis in ancient Egypt likely had a tangible effect on public health and productivity. Chronic infection, particularly in its advanced form, causes anemia, stunted growth, organ damage, and extreme fatigue.6 Given that Egypt’s economy was labor-intensive and reliant on the agricultural output of its Nile-fed lands, the toll on the working population—particularly peasants and corvée laborers—may have been substantial. Some scholars have suggested that recurrent parasitic diseases like schistosomiasis may have reduced life expectancy and labor capacity, placing hidden constraints on state planning, construction, and warfare.7

Priestly and elite classes, who enjoyed greater access to filtered water and better hygiene, may have had lower rates of infection, further exacerbating the health gap between classes. Yet even royal mummies have tested positive for S. haematobium, suggesting the disease did not discriminate entirely.8

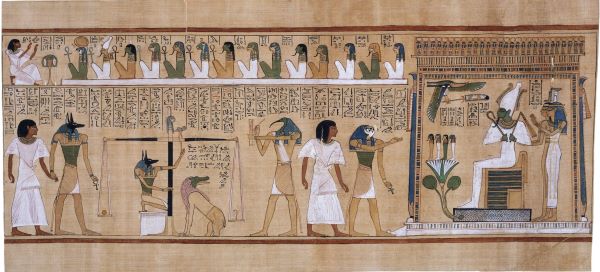

Schistosomiasis and Ritual Purity

Ancient Egyptian religious texts contain allusions to ritual cleanliness and bodily fluids that some scholars have interpreted in light of schistosomiasis. The disease’s most visible symptom—hematuria, or blood in the urine—may have been seen as a defilement or impurity, especially among males. In fact, Greek physicians referring to Egypt called it “male menstruation,” reflecting this cultural interpretation.9 The practice of ritual purification by water, widespread in Egyptian religious life, ironically may have exposed participants to further infection.

This contradiction—where the agent of purification became the vector of affliction—embeds schistosomiasis in a symbolic matrix. It was a disease that subverted ritual, defiled the sacred, and afflicted even the powerful. In that sense, it was a curse not of divine vengeance but of ecological entanglement and systemic ignorance.

Legacy and Modern Echoes

The disease did not vanish with the fall of the pharaohs. In fact, Egypt remained one of the world’s most heavily affected areas until the late 20th century, when mass drug administration with praziquantel began to reduce its prevalence.10 The construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s, while solving irrigation problems, inadvertently increased snail habitats and led to a resurgence of schistosomiasis in some regions.11 The “curse” thus proved persistent—embedded in the environmental infrastructure itself. The notion of a “Pharaoh’s Curse” becomes, in this light, a tragic irony. It was not the tomb’s opening that doomed Carter’s team, but rather the river’s bounty that slowly poisoned millions over centuries. Chronic schistosomiasis was a disease of water and ritual, of empire and ecology—a true curse written not in hieroglyphs, but in blood and bladders.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Peter J. Hotez et al., Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases: The Neglected Tropical Diseases and Their Impact on Global Health and Development (Washington, D.C.: ASM Press, 2021), 97.

- David J. Gibson, The Evolution of Parasitism in Animals (London: Springer, 2020), 244.

- Marc Armand Ruffer, “Note on the Presence of Bilharzia Haematobia in Egyptian Mummies of the Twentieth Dynasty,” British Medical Journal 1, no. 2610 (1910): 16.

- Anne-Marie Le Bras et al., “Detection of Schistosoma Haematobium Antigens in Mummies,” The Lancet 341, no. 8855 (1993): 1296–97.

- John N. Cross, “The Burden of Blood: Schistosomiasis in Ancient Egypt,” Journal of Egyptian Medical Studies 12, no. 3 (2016): 183–99.

- World Health Organization, Schistosomiasis: Progress Report 2001–2011 and Strategic Plan 2012–2020 (Geneva: WHO Press, 2013), 18.

- Gerald D. Hart, “Disease in Ancient Egypt,” The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 86, no. 8 (1993): 469–73.

- Zahia Ismail et al., “Schistosomiasis in Royal Mummies: Evidence and Implications,” Ancient Science and Medicine 5, no. 2 (2008): 212–25.

- Thomas G. Benedek, “Ancient Medical Writers on Schistosomiasis,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 49, no. 3 (1975): 357–65.

- Mahmoud El-Baz, “National Control of Schistosomiasis in Egypt: From the Nile to the Delta,” Tropical Medicine & International Health 22, no. 1 (2017): 12–19.

- Mohamed Y. El-Kassas, “Environmental Consequences of the Aswan High Dam,” Science 170, no. 3956 (1970): 825–30.

Bibliography

- Benedek, Thomas G. “Ancient Medical Writers on Schistosomiasis.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 49, no. 3 (1975): 357–65.

- Cross, John N. “The Burden of Blood: Schistosomiasis in Ancient Egypt.” Journal of Egyptian Medical Studies 12, no. 3 (2016): 183–99.

- El-Baz, Mahmoud. “National Control of Schistosomiasis in Egypt: From the Nile to the Delta.” Tropical Medicine & International Health 22, no. 1 (2017): 12–19.

- El-Kassas, Mohamed Y. “Environmental Consequences of the Aswan High Dam.” Science 170, no. 3956 (1970): 825–30.

- Gibson, David J. The Evolution of Parasitism in Animals. London: Springer, 2020.

- Hart, Gerald D. “Disease in Ancient Egypt.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 86, no. 8 (1993): 469–73.

- Hotez, Peter J., et al. Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases: The Neglected Tropical Diseases and Their Impact on Global Health and Development. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press, 2021.

- Ismail, Zahia, et al. “Schistosomiasis in Royal Mummies: Evidence and Implications.” Ancient Science and Medicine 5, no. 2 (2008): 212–25.

- Le Bras, Anne-Marie, et al. “Detection of Schistosoma Haematobium Antigens in Mummies.” The Lancet 341, no. 8855 (1993): 1296–97.

- Ruffer, Marc Armand. “Note on the Presence of Bilharzia Haematobia in Egyptian Mummies of the Twentieth Dynasty.” British Medical Journal 1, no. 2610 (1910): 16.

- World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis: Progress Report 2001–2011 and Strategic Plan 2012–2020. Geneva: WHO Press, 2013.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.