The internet did not invent falsehood, but it has weaponized it.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the span of a single generation, the internet has transformed from a static, text-heavy repository of academic and governmental information into a sprawling digital ecosystem that touches virtually every aspect of human life. It has democratized access to knowledge, fostered global communities, and given a platform to voices once marginalized. Yet alongside these transformative achievements, it has also become an incubator for a darker force: the mass proliferation of misinformation and disinformation. This phenomenon threatens not only individual understanding but also democratic institutions, public health, and social cohesion at a global scale.

Defining the Terrain: Misinformation vs. Disinformation

To begin unpacking the impact of online falsehoods, it is essential to distinguish between misinformation and disinformation. Though often used interchangeably, they describe different intentions behind the spread of false content.

- Misinformation refers to false or inaccurate information shared without intent to deceive. It is often spread by individuals who believe what they are sharing is true.

- Disinformation, by contrast, is deliberately false content crafted and disseminated with the express purpose of deceiving, manipulating public opinion, sowing discord, or achieving political, financial, or ideological goals.¹

The distinction is important: while misinformation may emerge from confusion or ignorance, disinformation is a calculated act—weaponized untruth masquerading as fact.

The Perfect Storm: Why the Internet Fuels Falsehoods

The architecture of the internet itself facilitates the spread of both misinformation and disinformation. Several features make it a uniquely powerful engine for these phenomena:

Decentralization and Democratization

The internet abolished the traditional gatekeepers of information—editors, publishers, and professional journalists. While this empowered ordinary users to share their voices, it also allowed unvetted, unverified content to be disseminated with equal prominence. An individual tweet, YouTube video, or Reddit post can reach millions without any editorial scrutiny or factual verification.²

Algorithmic Amplification

Social media platforms are engineered to maximize engagement, not truth. Algorithms prioritize content that elicits strong emotional reactions—outrage, fear, joy—which falsehoods often provoke more effectively than measured truths. A 2018 study published in Science found that false news stories on Twitter spread significantly faster and more broadly than true ones, especially in the realm of politics.³

Virality and Speed

Information can go “viral” within minutes. The velocity at which posts are shared and reshared makes it difficult to contain or correct false narratives. Once a lie has circled the globe, even official corrections or fact-checks struggle to gain traction, falling victim to what psychologists call the “continued influence effect.”⁴

Echo Chambers and Filter Bubbles

Recommendation algorithms tailor content to users’ preferences, reinforcing existing beliefs. Over time, users become ensconced in echo chambers where their views are constantly affirmed, and opposing perspectives are marginalized or vilified.⁵ This radicalization of belief systems creates fertile ground for both misinformation and disinformation.

Real-World Consequences

The effects of digital falsehoods are not confined to the realm of online debate. They spill over with dire consequences.

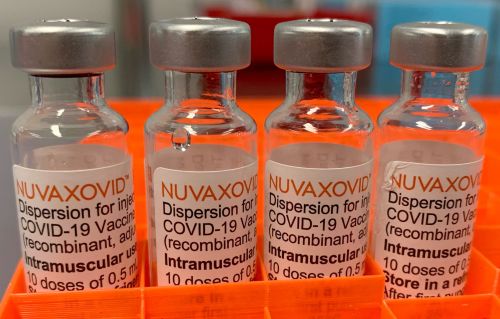

Public Health Crises

During the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories, fake cures, and vaccine misinformation spread like wildfire. False claims about microchips in vaccines, “plandemics,” and miracle treatments like ivermectin eroded trust in science and public institutions. In some cases, they led to vaccine hesitancy, increased infection rates, and unnecessary deaths.⁶

Electoral Manipulation and Democratic Erosion

Perhaps the most infamous example of disinformation’s political impact was Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Using troll farms and coordinated bot networks, Russian operatives disseminated divisive content, fabricated news stories, and orchestrated astroturfed social movements to fracture the American electorate.⁷ The Capitol riot on January 6, 2021, was partly fueled by the widespread acceptance of the false claim that the 2020 election was stolen—a narrative that gained momentum on digital platforms.⁸

Violence and Radicalization

Online disinformation has incited real-world violence. The rise of QAnon, an unfounded conspiracy theory alleging a global cabal of child traffickers, has led adherents to commit kidnappings, arson, and other crimes.⁹ Similarly, false rumors spread through WhatsApp in India have triggered mob lynchings of innocent people accused of child abduction.¹⁰

Climate Change Denial

Despite overwhelming scientific consensus, digital platforms have become havens for climate change denial. Fossil fuel interests, political actors, and ideological groups have exploited the internet to cast doubt on climate science, often using bots, paid influencers, and shadow organizations to spread misleading information.¹¹

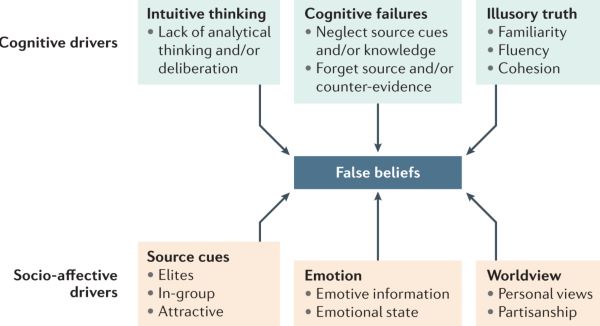

The Psychology Behind Belief

Why do people believe and share false information? Several cognitive and emotional factors are at play:

- Cognitive biases such as confirmation bias and the Dunning-Kruger effect skew perception and reinforce false beliefs.¹²

- Social identity theory suggests that aligning with a group—especially one that views itself as persecuted or enlightened—reinforces belief in group-shared narratives, even when they are demonstrably false.¹³

- Emotional resonance increases engagement. People are more likely to believe information that scares them, angers them, or validates their worldview.

- Information overload has made users more susceptible to heuristics and shortcuts, often relying on social proof (“everyone is sharing this”) rather than source credibility.¹⁴

Efforts at Containment

In response to growing concern, several countermeasures have emerged:

Platform Moderation

Tech companies like Meta, Google, and X (formerly Twitter) have taken steps—albeit inconsistently—to flag or remove misleading content, reduce the reach of known disinformation outlets, and partner with fact-checkers.¹⁵

Government Regulation

In some countries, governments have introduced laws aimed at curbing digital disinformation. The EU’s Digital Services Act, for example, holds platforms accountable for removing harmful content.¹⁶ However, regulatory action also raises thorny issues of free speech and censorship, particularly in authoritarian regimes that abuse “anti-fake news” laws to suppress dissent.

Media Literacy Campaigns

One of the most promising long-term strategies is the cultivation of media literacy—teaching individuals how to evaluate sources, question claims, and identify manipulation. Finland, often cited as a model, includes media literacy in school curricula and ranks as one of the most resistant nations to disinformation.¹⁷

AI and Verification Tools

Artificial intelligence is being developed to detect deepfakes, verify images, and trace the origins of viral content. These tools can assist journalists, researchers, and citizens in identifying falsehoods, though they remain imperfect and can be misused themselves.¹⁸

The Road Ahead

The fight against misinformation and disinformation is not one with a final victory, but an ongoing struggle. The internet, by its very nature, is an open and evolving frontier. As malicious actors adapt, so too must our defenses—legal, technological, and educational.

But the deeper challenge may be cultural. In an age of post-truth politics and epistemological chaos, where objective reality itself is often up for debate, the erosion of shared facts threatens the social contract. Rebuilding a civic culture that prizes truth over tribe, and inquiry over ideology, may be the most crucial task of all.

Conclusion

The internet did not invent falsehood, but it has weaponized it. The same platforms that connect us, empower us, and inform us have also become battlegrounds in an information war. To navigate this digital age responsibly, we must sharpen our discernment, demand accountability, and reaffirm our collective commitment to truth. In the words of Carl Sagan, “We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology, in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology.”¹⁹ That ignorance, now globalized and digitized, has consequences. And the time to confront them is now.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan, Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making, Council of Europe report DGI(2017)09 (Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2017).

- Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis, “Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online,” Data & Society, May 15, 2017.

- Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science 359, no. 6380 (2018): 1146–1151.

- Stephan Lewandowsky, Ullrich K.H. Ecker, and John Cook, “Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the ‘Post-Truth’ Era,” Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6, no. 4 (2017): 353–69.

- Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 2 (2017): 211–36.

- J. Scott Brennen et al., “Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation,” Reuters Institute, April 2020.

- David M. J. Lazer et al., “The Science of Fake News,” Science 359, no. 6380 (2018): 1094–96.

- Gordon Pennycook and David Rand, “The Implied Truth Effect,” Management Science 66, no. 11 (2020): 4944–57.

- Sheera Frenkel and Kevin Roose, “QAnon Followers Are Hijacking the #SaveTheChildren Movement,” New York Times, August 12, 2020.

- Adrien Friggeri et al., “Rumor Cascades,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 2014.

- Wardle and Derakhshan, Information Disorder.

- Lewandowsky, Ecker, and Cook, “Post-Truth Era.”

- Marwick and Lewis, “Media Manipulation.”

- Brennen et al., “COVID-19 Misinformation.”

- Pennycook and Rand, “The Implied Truth Effect.”

- Lazer et al., “Science of Fake News.”

- Wardle and Derakhshan, Information Disorder.

- Lewandowsky, Ecker, and Cook, “Post-Truth Era.”

- Carl Sagan, quoted in The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (New York: Random House, 1995).

Bibliography

- Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow. “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 2 (2017): 211–36.

- Brennen, J. Scott, Felix Simon, Philip N. Howard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. “Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, April 2020. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation.

- Frenkel, Sheera, and Kevin Roose. “QAnon Followers Are Hijacking the #SaveTheChildren Movement.” New York Times, August 12, 2020.

- Friggeri, Adrien, Lada A. Adamic, Dean Eckles, and Justin Cheng. “Rumor Cascades.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 2014.

- Lazer, David M. J., et al. “The Science of Fake News.” Science 359, no. 6380 (2018): 1094–96.

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich K.H. Ecker, and John Cook. “Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the ‘Post-Truth’ Era.” Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6, no. 4 (2017): 353–69.

- Marwick, Alice, and Rebecca Lewis. “Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online.” Data & Society, May 15, 2017.

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David Rand. “The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching Warnings to a Subset of Fake News Stories Increases Perceived Accuracy of Stories Without Warnings.” Management Science 66, no. 11 (2020): 4944–57.

- Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. New York: Random House, 1995.

- Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. “The Spread of True and False News Online.” Science 359, no. 6380 (2018): 1146–1151.

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. Council of Europe report DGI(2017)09. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2017.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.