These coin clipping rings operated in the shadows of cities and towns.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Trust, Currency, and Criminal Enterprise

In the medieval world, trust in currency was foundational to commerce, sovereignty, and social order. With coinage minted by kings and endorsed by divine right, its integrity underpinned feudal economies across Europe. Yet even in this system, monetary value was not fixed in abstraction—it depended on the weight and purity of precious metals in each coin. This created an irresistible opportunity for exploitation. Coin clipping, the fraudulent practice of shaving small amounts of metal from the edges of coins, became one of the most widespread and organized economic crimes of the medieval period. Often carried out by clandestine networks—coin clipping “rings”—the crime was both deeply disruptive and notoriously difficult to police. Its prevalence forced monarchs to repeatedly re-mint currencies, crack down on offenders, and wrestle with a financial crime that reflected the tension between centralized authority and decentralized criminal enterprise.

The Nature of Coin Clipping

Unlike modern fiat money, medieval coinage derived its value primarily from intrinsic metal content. A silver penny, for example, was expected to contain a specific weight of silver. Yet these coins circulated hand-to-hand for decades, sometimes centuries, and were susceptible to wear and, more dangerously, intentional tampering. Coin clipping involved shaving or cutting the edges of precious metal coins, collecting the filings, and melting them down to extract bullion. The modified coins remained in circulation, but each was slightly diminished—causing inflation, mistrust, and often hoarding of full-weight coins.

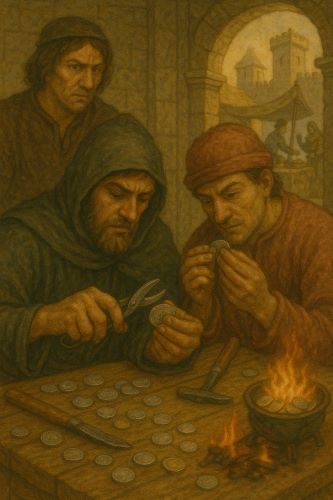

Clipping was more than a solitary act. In many cases, it was perpetrated by organized rings of offenders. These groups used rudimentary tools such as files, knives, and punches to deface coins, then coordinated the sale or melting of the metal for profit.1 Because the difference in weight was often subtle, it was difficult for merchants and the public to detect unless coins were weighed individually—a time-consuming and impractical process in most daily transactions.

Economic Consequences and Public Panic

The consequences of widespread clipping were severe. As clipped coins circulated, they undermined the trustworthiness of currency, prompting people to weigh or reject suspect coins and hoard unblemished ones. This disrupted trade and created panic in markets, especially in urban centers where currency volume was high. In England, France, the Holy Roman Empire, and Italy, periodic currency crises forced rulers to withdraw debased or clipped coins and issue new ones—a costly and logistically daunting process.2

A particularly severe episode occurred in England under Edward I (r. 1272–1307), who initiated a full recoinage in 1279 to address extensive clipping of silver pennies. The recoinage involved not only replacing damaged coins but also instituting edge inscriptions (legendary inscriptions on coin rims) to deter clipping—a practice that would later influence modern milled edges.3 Yet even with these reforms, the underlying problem persisted, rooted in the ease of execution and the high incentive to exploit the system.

The Role of Coin Clipping Rings

Coin clipping was rarely an isolated or opportunistic act. Many offenders worked in organized groups, sharing equipment and coordinating distribution. These rings operated in secrecy, sometimes within urban enclaves or itinerant communities. Members might include blacksmiths, money handlers, or others familiar with the physical properties of coinage.4 Some rings were transregional, moving across borders to exploit different monetary systems and evade detection.

Authorities often blamed Jews and foreign merchants, scapegoating minority communities as culprits in clipping scandals. The 1279–1281 arrest and execution of over 280 Jews in England on charges of coin clipping exemplifies this trend. While there is evidence that some individuals participated, many historians believe the Crown used the charges as a pretext for confiscating Jewish wealth and property, especially as Jewish communities served as royal financiers.5 This politicization of clipping cases shows how monetary crimes could be manipulated for broader social and economic agendas.

Legal Responses and Punishments

Given the damage to royal authority and economic order, medieval rulers treated coin clipping as a capital offense. Punishments were severe, often involving mutilation or execution. In England, the 1275 Statute of the Jewry and the 1280 Statute of Westminster laid out harsh penalties for clippers, including hanging or burning.6

Secular courts and ecclesiastical institutions collaborated in rooting out clipping rings, particularly when the crime was associated with sacrilege, such as melting coins consecrated in church offerings. Local officials were empowered to investigate suspected clippers, and some cities created watch systems or guild inspections to detect light-weight coins.

However, detection remained a challenge. Weighing coins was not routine outside major transactions, and counterfeiters grew more sophisticated in hiding their alterations. Some coin clippers even learned to replace shavings with tin or copper fillings to disguise the loss of weight.7 The battle between coiners and authorities became a technological arms race, paralleling the development of more secure minting methods.

Cultural Memory and Legacy

Coin clipping occupied a vivid space in medieval imagination and moral discourse. It was associated not only with greed and treason but with the broader theme of violating divine order. Since money bore the image of the king—often considered God’s anointed—damaging a coin was symbolically damaging the body politic and the sacred chain of authority.8 Chronicles and sermons described coin clippers as “economic heretics,” and the crime found its way into literature and civic drama.

The long-term response to clipping shaped the evolution of minting technology. By the early modern period, innovations such as milled coin edges, reeding, and more uniform alloys were adopted to deter tampering.9 But the persistence of coin clipping over centuries underscores the difficulty of maintaining monetary integrity in premodern economies—and the enduring ingenuity of those who sought to undermine it.

Conclusion: Fraud in the Currency of Trust

Coin clipping rings in the medieval world exploited a core vulnerability of the era’s monetary system: the physical nature of value. In a time when silver and gold were not just representations of wealth but wealth itself, even small acts of fraud had systemic repercussions. Clipping revealed the fragility of economic trust, the limits of state enforcement, and the dangers of scapegoating in the face of crisis.

These rings operated in the shadows of cities and towns, testing the reach of royal power and the resilience of civic institutions. Their story is not just one of crime, but of the complex relationship between material exchange and social belief—between the coin in hand and the faith behind its value.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Peter Spufford, Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 176–179.

- John H. Munro, “The Monetary Origins of the ‘Price Revolution’: South German Silver Mining, Merchant-Banking, and Venetian Commerce, 1470–1540,” in Global Connections and Monetary History, 1470–1800, ed. Dennis O. Flynn, Arturo Giráldez, and Richard von Glahn (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), 29.

- Rory Naismith, Money and Power in Anglo-Saxon England: The Southern English Kingdoms 757–865 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 224–226.

- Thomas K. Heebøll-Holm, Ports, Piracy and Maritime War: Logistics and the Atlantic Economy in the Fourteenth Century (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 82.

- Robin R. Mundill, England’s Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 1262–1290 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 100–103.

- William Stubbs, Select Charters and Other Illustrations of English Constitutional History, 9th ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913), 376–377.

- Robert Lopez and Irving Raymond, Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World (New York: Columbia University Press, 1955), 213.

- Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, trans. L.A. Manyon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), 120–123.

- Philip Grierson, Numismatics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975), 63–65.

Bibliography

- Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society. Translated by L.A. Manyon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- Grierson, Philip. Numismatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975.

- Heebøll-Holm, Thomas K. Ports, Piracy and Maritime War: Logistics and the Atlantic Economy in the Fourteenth Century. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Lopez, Robert, and Irving Raymond. Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World. New York: Columbia University Press, 1955.

- Mundill, Robin R. England’s Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 1262–1290. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Munro, John H. “The Monetary Origins of the ‘Price Revolution’: South German Silver Mining, Merchant-Banking, and Venetian Commerce, 1470–1540.” In Global Connections and Monetary History, 1470–1800, edited by Dennis O. Flynn, Arturo Giráldez, and Richard von Glahn, 17–50. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003.

- Naismith, Rory. Money and Power in Anglo-Saxon England: The Southern English Kingdoms 757–865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Spufford, Peter. Money and Its Use in Medieval Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Stubbs, William. Select Charters and Other Illustrations of English Constitutional History. 9th ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.