Taken together, these arguments form a mosaic of resistance. They range from misunderstandings of genetics to genuine critiques of corporate power.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Technology and Suspicion

Since their commercial introduction in the 1990s, genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have been the subject of intense scrutiny and suspicion. No other agricultural innovation has provoked such fierce cultural resistance. For scientists, GMOs represent a logical continuation of human intervention in nature, an acceleration of what selective breeding had long achieved. For critics, they symbolize intrusion, hubris, and danger.

The arguments deployed against GMOs are numerous, but they share certain rhetorical traits. They appeal to fear of the unnatural, to distrust of corporate power, and to deep anxieties about modern science. They persist not because they withstand scrutiny, but because they resonate with cultural narratives and political identities. The historian’s task is not only to catalog these objections but to trace their persistence across time and place.

Naturalness and the Rhetoric of Purity

Perhaps the most enduring objection to GMOs is that they are “unnatural.” This claim has appeared in countless slogans and campaigns. To say that “GMOs are unnatural, and therefore unsafe”1 is to employ the “appeal to nature” fallacy: the assumption that what is natural is safe, and what is unnatural is dangerous. History offers countless counterexamples, from arsenic to tobacco, both natural yet harmful.

The language of “Frankenstein foods” became a powerful media trope in Europe in the 1990s.2 The invocation of Mary Shelley’s tale of the unnatural creation evoked both horror and moral disgust. Critics also claimed that humanity had survived “thousands of years without GMOs” and thus did not need them,3 as though longevity itself were evidence of sufficiency. Indigenous or heirloom crops were held up as pure alternatives, romanticized as more wholesome or authentic.4

This cluster of arguments reveals less about scientific risk than about cultural desire. They reflect anxieties about purity and authenticity, about human boundaries with nature, and about technology as transgression. In the end, these arguments resist evidence precisely because they rest on intuition and symbolism rather than biology.

Health and Safety Myths

If purity arguments frame GMOs as morally corrupt, health myths cast them as physically dangerous. Critics often assert that GMOs are “poison” or “toxic,” phrases that gain traction precisely because they bypass nuance. The specter of cancer is repeatedly raised, often citing the discredited Seralini rat study, which was withdrawn after methodological flaws were exposed.5

Other claims invoke the unknown: “we don’t know the long-term effects.” This appeal to uncertainty is rhetorically effective, for it cannot be fully disproven. Yet GMOs have now been consumed for over two decades by billions of people, with no credible evidence of harm.6 Still, myths persist that they cause allergies, autism, infertility, or strange diseases not yet identified.7 These allegations are tied to cultural anxieties about modern illness and the search for culprits in a changing world.

Critics further claim that GMOs make food less nutritious or harder to digest. Ironically, some GMOs were created to enhance nutrition, as with Golden Rice enriched with vitamin A.8 Others conflate GMOs with food intolerances, suggesting that genetic modification is responsible for increases in gluten sensitivity or peanut allergies. No evidence substantiates this, yet repetition cements it in popular imagination.

Such myths illustrate the historical reality that new technologies in food have often been greeted with suspicion. Pasteurization and artificial fertilizers once faced similar accusations. In each case, fear of novelty blended with genuine health concerns to form arguments resistant to scientific rebuttal.

Ecological and Agricultural Concerns

Not all objections are couched in personal health. Many focus on ecological risk. One argument asserts that herbicide-tolerant crops have created “superweeds” resistant to glyphosate. Resistance does occur, but it is a product of farming practices rather than genetic modification itself.9 Weeds developed resistance to herbicides long before GM crops existed.

Similarly, critics argue that pest-resistant crops create “superbugs.” Over time, insects can evolve resistance to Bt toxins, but this is a case of evolutionary biology rather than intrinsic danger. Proper management can mitigate these effects. Yet the image of an out-of-control ecosystem, filled with monstrous weeds and insects, is rhetorically powerful.

Other claims suggest that GMOs kill bees or destroy biodiversity. These charges often conflate GMOs with pesticide use or with monoculture agriculture more generally.10 Cross-pollination, likewise, is presented as “contamination,” turning the natural process of pollen drift into a symbol of violation. Here the language of ecology becomes entangled with cultural anxieties about purity and control.

Historians may recognize echoes of earlier agricultural controversies, from fears about hybrid seeds to debates over chemical fertilizers. GMOs, like earlier technologies, are imagined as both ecological threat and cultural trespass.

Corporate Conspiracies and Political Suspicion

If nature and health form one axis of criticism, corporate power forms another. Critics frequently describe GMOs as a plot by Monsanto (now Bayer) to control the world’s food supply. The argument resonates because it mixes genuine concerns about corporate concentration with conspiratorial exaggeration.11

Similarly, critics insist that farmers are “forced” to buy GMO seeds annually. While it is true that patented seeds cannot legally be replanted, the same is true of many hybrid seeds. The difference lies not in genetic modification but in agricultural economics. Still, the idea of farmers trapped in dependency evokes deep sympathy.

Labeling debates also take on conspiratorial tones. The absence of mandatory labeling in some countries is presented as evidence of deception. More extreme claims assert that GMOs are a form of “bioterrorism” or part of a global “depopulation agenda”.12 Patents themselves are reframed as evidence of danger, though patents reflect legal structures rather than safety.

These arguments reflect a long history of suspicion toward industrial agriculture. They are rooted not in science but in political economy, in fears of corporate overreach and loss of farmer autonomy.

Scientific Misunderstandings

Perhaps the most striking category consists of arguments that betray basic misunderstandings of biology. Some critics claim that GMOs “contain dangerous chemicals,” as though genes themselves were toxins. Others believe that GMOs are “drenched in Roundup,” conflating herbicide tolerance with chemical saturation.

More fantastical claims assert that eating GMOs can “transfer genes into our bodies” or “change our DNA.” In reality, all food contains DNA, which is broken down during digestion. Yet the imagery of alien genes inserting themselves into human genomes is both vivid and frightening.

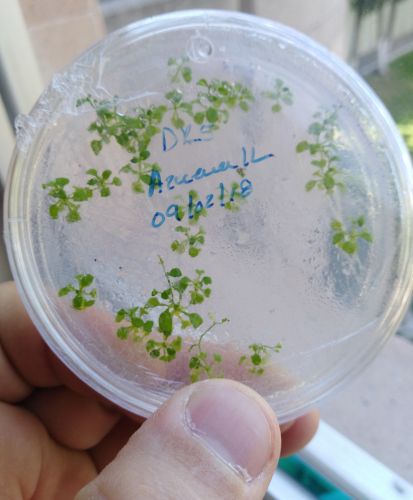

One of the most persistent myths is that of “fish genes in tomatoes.” In the 1990s, researchers experimented with inserting antifreeze proteins from cold-water fish into tomatoes to resist frost. The experiment was never commercialized, but the idea of “fish genes” became a durable cultural symbol.13 Some even argue that GMOs are “radioactive,” confusing gene transfer techniques with nuclear processes.

These misunderstandings highlight the distance between scientific practice and public imagination. Genes are imagined as discrete, dangerous substances rather than as information common to all life. The language of contamination and invasion reflects cultural fears more than biological realities.

Distrust of Testing and Regulation

Another cluster of arguments focuses on regulatory failure. Critics claim that GMOs are not tested enough, ignoring the fact that they undergo some of the most stringent testing of any food in history.14 Others point to European restrictions, assuming bans reflect safety concerns rather than political compromise.

The refrain that “they haven’t been around long enough” persists despite three decades of consumption. Appeals to precaution, while understandable, become endless deferrals when evidence is continually dismissed. Claims that countries rejecting GMOs are healthier often rely on selective comparisons, ignoring confounding social and economic factors.

These arguments reveal a deeper mistrust of institutions. The objection is not to data but to authority. Regulators and scientists are imagined as compromised, leaving suspicion to flourish. The historian recognizes here a familiar pattern in modernity: the erosion of trust in expertise.

Cultural and Subjective Claims

Finally, some objections are more cultural than scientific. Critics argue that GMOs “do not taste as good,” a subjective claim given universal form. Others insist that GMOs exist only for corporate profit, not for feeding the hungry. Still others point to organic farming as proof that GMOs are unnecessary.15

These arguments reveal the cultural identity invested in food. Taste, tradition, and authenticity matter deeply. To reject GMOs is, for some, to embrace a vision of purity, community, or resistance to industrialization. Here science cannot easily intervene, for the issue lies not in evidence but in meaning.

Conclusion: Fear as Cultural Inheritance

Taken together, these arguments form a mosaic of resistance. They range from misunderstandings of genetics to genuine critiques of corporate power, from appeals to purity to conspiracy theories of global control. They persist not because they survive scientific scrutiny but because they satisfy cultural needs.

For the historian, these objections reveal how food technologies become sites of cultural conflict. GMOs are more than crops; they are symbols in debates over nature, identity, and power. For the scientist, they are a reminder that evidence alone is insufficient. Persuasion requires attention to narrative, trust, and cultural meaning.

In the end, the fear of GMOs tells us less about genes than about ourselves.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Paul B. Thompson, Food Biotechnology in Ethical Perspective (New York: Springer, 1997), 89–92.

- Sheldon Krimsky, “An Illusory Consensus behind GMA Health Assessment” Science, Technolgy, & Human Values 40:6 (2015).

- Alan McHughen, Pandora’s Picnic Basket: The Potential and Hazards of Genetically Modified Foods (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 41.

- Jack Ralph Kloppenburg, First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 1492–2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 214.

- Gilles-Eric Séralini et al., “Long Term Toxicity of a Roundup Herbicide and a Roundup-Tolerant Genetically Modified Maize,” Food and Chemical Toxicology 50, no. 11 (2012): 4221–4231. Retracted 2013.

- National Academy of Sciences, Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2016), 107–110.

- Nina V. Fedoroff and Nancy Marie Brown, Mendel in the Kitchen: A Scientist’s View of Genetically Modified Foods (Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 2004), 75–78.

- Adrian C. Dubock, “Golden Rice: To Combat Vitamin A Deficiency for Public Health,” Nutrition Reviews 72, no. 1 (2019): 30–40.

- Andrew Kniss, “Genetically Engineered Herbicide-Resistant Crops and Herbicide-Resistant Weed Evolution in the United States,” Weed Science 66, no. 2 (2017): 260–273.

- Margaret Mellon and Jane Rissler, The Ecological Risks of Engineered Crops (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 55–62.

- Philip H. Howard, Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What We Eat? (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), 91–93.

- Michael Specter, Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives (New York: Penguin, 2009), 143–147.

- Timothy Caulfield, The Cure for Everything: Untangling Twisted Messages about Health, Fitness, and Happiness (Toronto: Viking, 2011), 201.

- FAO/WHO, Safety Assessment of Foods Derived from Genetically Modified Microorganisms (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization, 2001), 19–22.

- Peter Pringle, Food, Inc.: Mendel to Monsanto—the Promises and Perils of the Biotech Harvest (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 174–176.

Bibliography

- Caulfield, Timothy. The Cure for Everything: Untangling Twisted Messages about Health, Fitness, and Happiness. Toronto: Viking, 2011.

- Dubock, Adrian C. “Golden Rice: To Combat Vitamin A Deficiency for Public Health.” Nutrition Reviews 72, no. 1 (2019): 30–40.

- FAO/WHO. Safety Assessment of Foods Derived from Genetically Modified Microorganisms. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization, 2001.

- Fedoroff, Nina V., and Nancy Marie Brown. Mendel in the Kitchen: A Scientist’s View of Genetically Modified Foods. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 2004.

- Howard, Philip H. Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What We Eat? New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Kloppenburg, Jack Ralph. First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 1492–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Kniss, Andrew. “Genetically Engineered Herbicide-Resistant Crops and Herbicide-Resistant Weed Evolution in the United States.” Weed Science 66, no. 2 (2017): 260–273.

- Krimsky, Sheldon. “An Illusory Consensus behind GMA Health Assessment.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 40:6 (2015).

- McHughen, Alan. Pandora’s Picnic Basket: The Potential and Hazards of Genetically Modified Foods. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Mellon, Margaret, and Jane Rissler. The Ecological Risks of Engineered Crops. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.

- National Academy of Sciences. Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2016.

- Pringle, Peter. Food, Inc.: Mendel to Monsanto—the Promises and Perils of the Biotech Harvest. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

- Séralini, Gilles-Eric, et al. “Long Term Toxicity of a Roundup Herbicide and a Roundup-Tolerant Genetically Modified Maize.” Food and Chemical Toxicology 50, no. 11 (2012): 4221–4231. Retracted 2013.

- Specter, Michael. Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Thompson, Paul B. Food Biotechnology in Ethical Perspective. New York: Springer, 1997.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.