When the argument is performative, when the frame is unfalsifiable, when attention is the prize rather than the pathway, the most powerful refusal is to starve the script of what it needs.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Framing the Problem

Not every disagreement is a debate. Debates presume shared rules: evidence counts, logic binds, and losing an argument changes a mind. The ecosystems built around flat earth claims, moon landing denial, and ancient alien evangelism do not operate by those rules. They are built for performance. They do not seek resolution. They seek attention.

Attention is not neutral. Attention is a resource that can be converted into social proof, algorithmic reach, and cash. When we argue with claims constructed to be unfalsifiable, we supply the very oxygen that keeps them burning. The paradox is simple: rising to the challenge does not extinguish the fire. It feeds it. The rational impulse to defend truth becomes the mechanism by which an anti-rational script secures the spotlight.1

The task, then, is not to “win” against positions that cannot be lost. It is to defend the conditions that make truth legible in public life. That defense begins, in some cases, by withholding the one thing that cannot be faked: our attention.

What You Are Really Up Against

For many adherents, these claims function as identity, not hypothesis. Motivated reasoning protects identity by filtering evidence through group commitments; contrary facts are felt as threats, not information.2 Conspiracy worldviews add additional armor. They attribute hidden agency to random events, treat anomalies as patterns, and offer the believer a gratifying role as one of the few who truly understand.3

Confidence rises as competence falls. The Dunning–Kruger effect shows how novices overestimate their grasp precisely because they do not know what they do not know.4 Pair that with the illusion of explanatory depth, in which people discover only under pressure how shallow their understanding actually is, and you have a psychology tuned to double down, not reconsider.5

When this psychology meets a performative arena, something else happens. The social reward is not belief accuracy but in-group applause for “owning” experts. Each exchange becomes a stage. The more the expert engages, the bigger the stage becomes.

The Debate Trap

The debate trap exploits asymmetry. It is quick to invent, slow to correct. A single video can launch six false claims in sixty seconds, while a careful response requires six paragraphs to explain context, method, and uncertainty.6 The tactic even has a name in rhetorical criticism: the Gish Gallop, a flood of weak points designed to exhaust rather than persuade. The goalposts move when you approach. The burden of proof is reversed when you supply evidence. “Just asking questions” becomes an alibi for insinuation.

Most corrosive is the unfalsifiable frame. Any contrary result is absorbed as proof of the plot. If imagery shows Earth’s curvature, the images are fabricated. If multiple nations verify the Apollo record, the nations are colluding. When empirical reality can only confirm the theory, conversation is no longer rational inquiry. It is a pageant.7

Attention Is Oxygen

Attention confers legitimacy. In mass media, equal time on a stage suggests equal standing. In digital systems, replies, stitches, duets, and quote-tweets tell algorithms the content is lively. That is how false balance works: by framing settled matters as open contests, media can mislead audiences into thinking there are two sides of comparable merit.8

The more you respond, the more the platform learns to promote the performance. Even refutations can heighten distribution. That is not an argument for silence in every case. It is an argument for strategic silence where attention is the principal currency.9

The Real Costs of Engaging

There are obvious costs. Every minute spent sparring with a content creator whose income depends on your attention is a minute not spent equipping the movable middle. The audience can come away confused, believing that evidence is a matter of opinion because the format suggests parity. Fringe claims recruit precisely by converting controversy into identity. Creators and moderators burn out while trolls stay fresh. The result is a public sphere noisier than it is wiser.10

Some costs are subtler. Constant defensive posture narrows the curriculum. We teach less of how we know and more of what we deny. We model to students and readers that the loudest claims define the agenda. That is not pedagogy. It is surrender on a new axis.

Principles for Strategic Non-Engagement

Refusal is not abdication. It is a decision to allocate scarce attention toward the highest-yield targets: bystanders and fence-sitters. Speak to them directly. Name the tactic before the lie appears so it loses surprise value. That is prebunking, or inoculation, and it draws on a long tradition in psychology.11

When you must correct, lead and end with the truth, and place the myth in the middle with warnings about the tactic. That structure limits repetition effects. It is sometimes called a truth sandwich.12 Set comment policies that explain why you do not debate foundational facts on your channels. Enforce them consistently. Choose messengers who are trusted by the audience you want to reach. Keep interventions short and canonical, and then step out of the performative ring.13

Case Studies

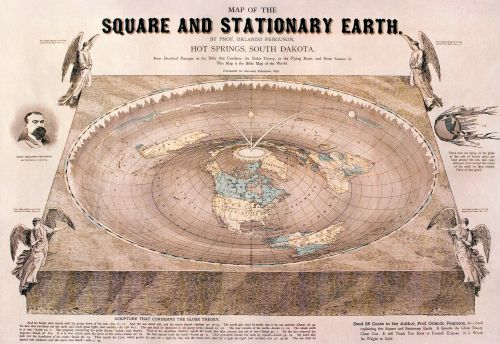

Flat Earth

Flat earth claims rarely present a single theory. They present a carousel. If the horizon looks flat to the naked eye, the Earth must be flat. If photos show curvature, the photos are faked. If one astronomical measurement is explained, another will be substituted. The point is not to converge on the truth. The point is to keep you on the hook.

Responders often supply geometry, optics, and geodesy. They describe ship hulls disappearing before masts, aircraft great-circle routes, star field rotations that reverse between hemispheres, and satellite-based positioning whose mathematics presumes a spheroid Earth. The presentation may be elegant. The result is usually the same. Counterevidence is recoded as part of the deception. The argument relocates to new terrain and demands you follow. The better course is to link briefly to a canonical explainer, mark the tactic for the bystander, and move on.14

Moon Landing Denial

Here the carousel turns on physics and photography. The Van Allen belts are presented as an impassable wall rather than a zone whose risks were managed by trajectory and exposure time. Flags appear to ripple in a vacuum when what the video shows is momentum without air resistance. Shadows that do not run parallel are treated as evidence of studio lighting when perspective on uneven terrain is fully sufficient.

Each correction is met with an auxiliary rescue hypothesis. If that one fails, another is added. The architecture is not cumulative evidence but cumulative suspicion. In this architecture, debate is not a method. It is a marketing strategy.15

Ancient Alien Theories

Ancient alien speculation flatters the present by insulting the past. It reframes complex engineering and cultural achievement as evidence of extraterrestrial intervention because the presenter cannot imagine that human beings without modern tools could solve hard problems. The pattern is not just epistemic error. It is historical erasure. By denying that Egyptians, Maya, or Andean engineers could build what they built, these narratives smuggle older racial hierarchies into new entertainment.16

There is an obligation to answer for the sake of the audience whose heritage is being written out. The way to do that is not by platforming the show. It is by teaching method: quarry marks, tool signatures, logistics, experimental archaeology, and the long apprenticeship of craft. When we show how we know, wonder does not shrink. It grows.17

When Engagement May Still Be Warranted

There are exceptions. In a classroom or museum, duty of care can require a concise correction for the whole audience. In a newsroom, a brief note appended to a viral falsehood can prevent spread. In your own channels, a single, bounded reply that links to a canonical page may be warranted when silence would be read as assent.

Boundaries matter. Set a time limit. Make one reply, not a thread. Control the frame and exit. The goal is education, not combat.

What To Do Instead

Build a library of short, well-designed explainers that you can link rather than argue. Teach the methods behind the conclusions: measurement, replication, error correction, peer review, and the discipline of changing one’s mind when the data demand it. Invest in prebunking pieces that explain argument tactics before they appear. Elevate positive exemplars of human ingenuity that conspiracies routinely erase. Curate your channels to reward curiosity and slow reactive spats.18

Design friction where necessary. Slow-mode comments when a post begins to attract performative denial. Require first-time commenters to read and accept a short policy that explains why you do not host debates about settled facts. Do not apologize for these rules. They exist to keep the conversation rational for those who can still be reached.

Scripts and Boundaries

Readers appreciate clarity. You can say: “We do not debate settled facts here. If you are curious about how we know, here is a short explainer. If you wish to perform an argument, this is not the venue.” In private messages: “I will send one resource. I will not continue a back-and-forth. If you read it with good faith and have a question about the method, I am here.”

These scripts are not walls against people. They are guardrails against a style of conversation that is not one.

Ethical and Historical Context

We have been here before. Creation science in the schoolroom sought to win not by evidence but by mandatory balance. Tobacco strategists funded doubt so that doubt would function as policy. Climate contrarians learned to exploit journalistic norms that treat every story as a two-hander. Manufactured doubt is a method. Its goal is to keep the referee from blowing the whistle.19

Refusing performance is part of learning from that history. It keeps the classroom for teaching, not for theater. It keeps the newsroom for verification, not for spectacle. It keeps public attention from being harvested by those who would turn reasoning into a sport with no rules.

Conclusion

Silence can be abdication. It can also be discipline. When the argument is performative, when the frame is unfalsifiable, when attention is the prize rather than the pathway, the most powerful refusal is to starve the script of what it needs. That refusal does not retreat from public life. It protects it.

Do not ask whether you can win the debate. Ask whether the debate is designed for anyone to win. Then spend your scarce attention where it moves minds. The point is not to own the opponent. It is to keep the space of reason open for those who still want to think.

Appendix

Notes

- Lee McIntyre, Post-Truth (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018).

- Dan M. Kahan, “Cultural Cognition as a Conception of the Cultural Theory of Risk,” in Handbook of Risk Theory (Springer, 2008).

- Rob Brotherton, Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015).

- Justin Kruger and David Dunning, “Unskilled and Unaware of It,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, no. 6 (1999).

- Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil, “The Misunderstood Limits of Folk Science,” Cognitive Science 26, no. 5 (2002).

- Lee McIntyre, How to Talk to a Science Denier (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), on asymmetries of correction; see also John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky, The Debunking Handbook 2020 (St. Lucia: University of Queensland, 2020).

- Cass R. Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule, “Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures,” Journal of Political Philosophy 17, no. 2 (2009).

- Maxwell T. Boykoff and Jules M. Boykoff, “Balance as Bias,” Global Environmental Change 14, no. 2 (2004).

- Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts, Network Propaganda (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloomsbury, 2010).

- William J. McGuire, “Inducing Resistance to Persuasion,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1 (1964); Sander van der Linden et al., “Inoculating the Public Against Misinformation,” Global Challenges 1, no. 2 (2017).

- George Lakoff, “A Truth Sandwich,” public communication guidance, 2018.

- John Cook, Ullrich Ecker, and Stephan Lewandowsky, “Misinformation and How to Correct It,” in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences (Wiley, 2015).

- Glenn Branch, “Flat-Earthery Will Get You Nowhere,” Skeptical Inquirer 44, no. 4 (2020).

- James Oberg, UFOs & Outer Space Mysteries (New York: Donning, 1982), chs. on Apollo hoaxes; also NASA historical publications on Apollo mission hazards and mitigation.

- Jason Colavito, The Cult of Alien Gods (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2005); see also Sarah E. Bond, “Pseudoarchaeology and White Supremacy,” Hyperallergic, 2017.

- Experimental archaeology surveys in Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory routinely document human solutions to ancient engineering without resort to exotica.

- Stephan Lewandowsky, Ullrich Ecker, and John Cook, “Beyond Misinformation,” Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6, no. 4 (2017).

- Oreskes and Conway, Merchants of Doubt; Boykoff and Boykoff, “Balance as Bias.”

Bibliography

- Benkler, Yochai, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Bond, Sarah E. “Pseudoarchaeology and the Racism behind Ancient Aliens.” Hyperallergic, November 3, 2018.

- Boykoff, Maxwell T., and Jules M. Boykoff. “Balance as Bias: Global Warming and the US Prestige Press.” Global Environmental Change 14, no. 2 (2004): 125–136.

- Branch, Glenn. “Flat-Earthery Will Get You Nowhere.” Skeptical Inquirer 44, no. 4 (2020).

- Brotherton, Rob. Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015.

- Colavito, Jason. The Cult of Alien Gods: H. P. Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2005.

- Cook, John, and Stephan Lewandowsky. The Debunking Handbook 2020. St. Lucia: University of Queensland, 2020.

- Cook, John, Ullrich Ecker, and Stephan Lewandowsky. “Misinformation and How to Correct It.” In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2015.

- Kahan, Dan M. “Cultural Cognition as a Conception of the Cultural Theory of Risk.” In Handbook of Risk Theory. Dordrecht: Springer, 2008.

- Kruger, Justin, and David Dunning. “Unskilled and Unaware of It.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, no. 6 (1999): 1121–1134.

- Lakoff, George. “A Truth Sandwich.” Public communication guidance, 2018.

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich K. H. Ecker, and John Cook. “Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the ‘Post-Truth’ Era.” Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6, no. 4 (2017): 353–369.

- McGuire, William J. “Inducing Resistance to Persuasion.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1 (1964): 191–229.

- McIntyre, Lee. Post-Truth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

- McIntyre, Lee. How to Talk to a Science Denier. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021.

- Oberg, James. UFOs & Outer Space Mysteries. New York: Donning, 1982.

- Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. Merchants of Doubt. New York: Bloomsbury, 2010.

- Rozenblit, Leonid, and Frank C. Keil. “The Misunderstood Limits of Folk Science.” Cognitive Science 26, no. 5 (2002): 521–562.

- Sunstein, Cass R., and Adrian Vermeule. “Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures.” Journal of Political Philosophy 17, no. 2 (2009): 202–227.

- van der Linden, Sander, Anthony Leiserowitz, Seth Rosenthal, and Edward Maibach. “Inoculating the Public Against Misinformation.” Global Challenges 1, no. 2 (2017): 1600008.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.