Across the long history traced here, moments of technological change repeatedly provoke the same fear: that creativity has been emptied of its human core.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Beauty Became Mechanical

The nineteenth century marked a profound rupture in the history of aesthetics, one that reached beyond economics or technology and into the moral imagination of culture itself. For the first time, beauty became subject to industrial logic on a mass scale. Machines did not merely accelerate production or lower costs. They transformed the very conditions under which beauty was made, perceived, and valued. Objects once shaped by visible human effort were now replicated endlessly by mechanical processes that concealed the hand of the maker and obscured the story of their creation. This transformation unsettled Victorians not because it introduced ugliness, but because it produced beauty without apparent human presence, intention, or struggle. The fear was not that machines could not make pleasing things, but that they could make them too well, too easily, and too impersonally.

Industrialization collapsed long-standing assumptions about how value was created in art and design. Craft traditions had bound beauty to time, skill, and embodied knowledge. A carved chair or woven textile carried within it the trace of human intention, discipline, and limitation. Machine production disrupted this moral economy. Identical objects emerged at scale, detached from individual makers and indifferent to locality. Beauty appeared severed from effort. For critics shaped by Romantic, medievalist, and moral traditions, this separation felt dangerous. Aesthetic pleasure without visible labor seemed ethically thin, even deceptive, as if form had been hollowed out and refilled with surface appeal alone.

Thinkers such as John Ruskin and William Morris framed this shift as a cultural crisis rather than a technical one. Their critiques were not reactions against machines per se, but against what mechanization appeared to do to human creativity, dignity, and moral responsibility. If art could be produced without human struggle, what did beauty signify? If ornament could be stamped rather than shaped, where did intention reside? The machine became a symbol of a deeper anxiety: that creativity itself was being reduced to pattern, repetition, and surface effect. Beauty, once understood as a moral and social achievement, risked becoming decorative noise.

This anxiety emerged at a moment of unprecedented creative expansion and aesthetic saturation. Industrialization multiplied access to designed objects, textiles, musical instruments, printed images, and architectural ornament on a scale never before imagined. Everyday life became more visually and materially rich, not less. Parlors, streets, and homes filled with pattern, color, and ornament that would once have been reserved for elites. The Victorian panic over “soulless” beauty was therefore not a rejection of abundance itself, but a struggle to reconcile abundance with inherited ideas about meaning and value. This essay argues that such fears, while historically understandable, misidentified the source of creativity. Machine-made culture did not destroy meaning. It forced a reckoning with where meaning had always resided, not in the purity of tools or processes, but in human judgment, intention, and use under changing conditions.

Before the Machine: Craft, Labor, and Moral Meaning

Before industrialization, craft was not merely a method of production. It was a moral framework through which labor, identity, and value were understood. Skilled making bound the worker to the object through time, effort, and bodily knowledge. Whether in stone carving, weaving, metalwork, or woodworking, the visible marks of labor were understood as evidence of care and intention. Objects bore the imprint of human limitation and judgment, and this imperfection was not a flaw but a sign of authenticity. Beauty was inseparable from the conditions of its making, and the act of making itself carried ethical significance.

Craft traditions also embedded production within dense social structures that reinforced meaning over generations. Guilds regulated training, standards, wages, and the transmission of skill through long apprenticeships and formal progression to mastery. Learning was slow, embodied, and relational, requiring years of repetition under supervision rather than abstract instruction. Knowledge passed from hand to hand, eye to eye, not from blueprint to machine. This system did more than ensure quality control. It created continuity and social belonging. Makers were not interchangeable laborers but recognized participants in a lineage of practice that conferred identity, status, and responsibility within a community.

Labor, in this context, carried explicit ethical weight. To work well was to act responsibly toward materials, patrons, and fellow craftsmen. Craft demanded attention, patience, and judgment, virtues that were inseparable from the finished object. Time spent making was not an inefficiency to be eliminated but a necessary condition of value. The effort embedded in an object justified its worth and commanded respect from users. Long before Victorian critics articulated their objections to mechanization, European craft culture had already linked moral seriousness to the pace, difficulty, and discipline of work itself.

These assumptions shaped pre-industrial aesthetics at every level. Ornament was not decoration applied after the fact, but an extension of structure, technique, and material understanding. Design emerged from the constraints of tools and substances rather than being imposed externally. A chair, a textile, or a building communicated its purpose and method of construction visibly through joinery, weave, or stonework. Form and function were not yet conceptually separated. The honesty of an object lay in its legibility, in the ability of a viewer to sense how it had been made, how it functioned, and the skill required to bring it into being.

It was this moral and aesthetic ecology that industrialization would profoundly disrupt. Victorian critics did not invent the association between craft and meaning. They inherited it, often idealized it, and then watched it erode rapidly. When machines replaced hands, they appeared to sever the visible link between labor and form that had anchored beauty to human experience for centuries. Understanding this pre-industrial framework is essential, because the later fear of “soulless” machine-made culture was not simply resistance to novelty or nostalgia for the past. It was grief over the loss of a system in which creativity, labor, social identity, and moral value had once seemed tightly and intelligibly bound together.

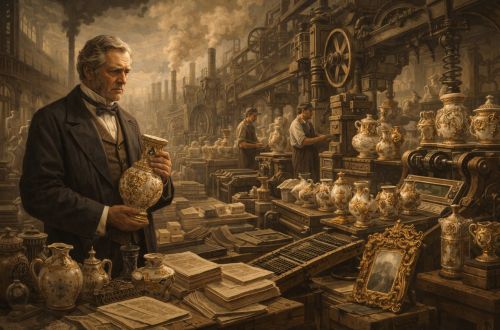

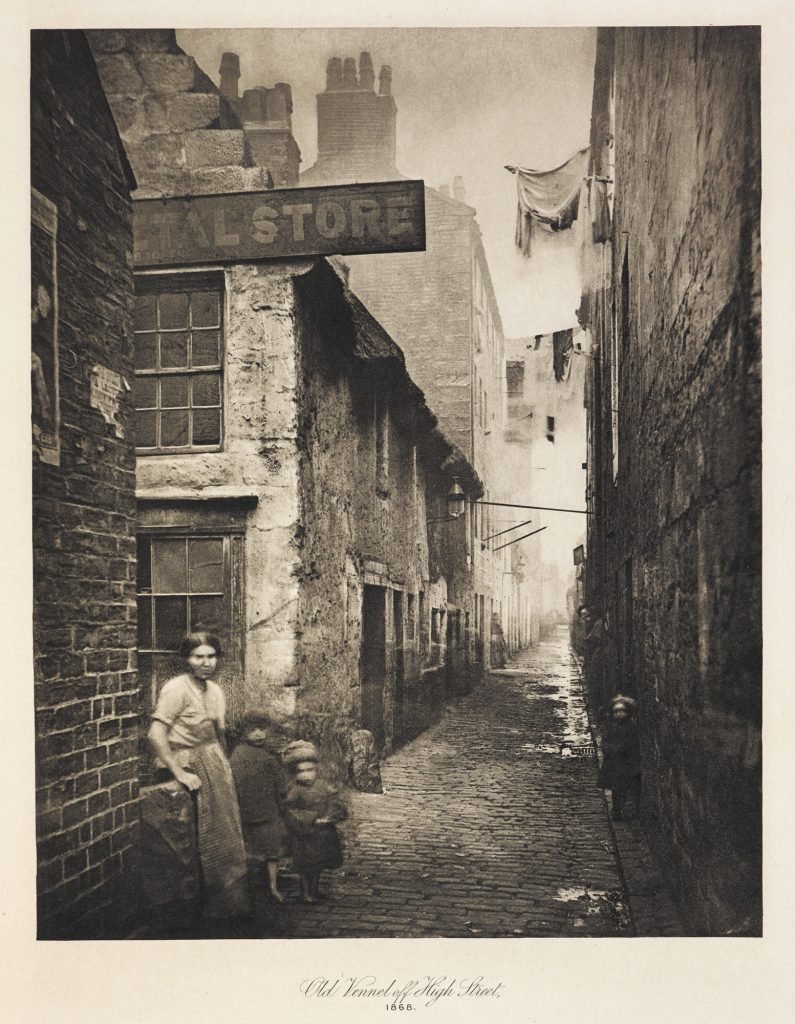

Industrialization and the Shock of Scale

Industrialization did not simply introduce new tools into existing systems of production. It transformed scale itself, altering how objects were conceived, produced, distributed, and encountered in everyday life. Factories replaced workshops, and machines multiplied output beyond anything craft traditions had prepared society to interpret. What had once been rare and local became abundant and uniform, circulating far from sites of manufacture. This expansion unsettled not only economic arrangements but aesthetic expectations. Beauty was no longer encountered as an exception or a culmination of effort. It became ambient, repeated, and omnipresent, woven into the texture of daily experience. The shock lay in realizing that aesthetic form could be detached from rarity without disappearing.

Scale changed the relationship between maker and object first. In factory production, labor was divided into discrete tasks, each abstracted from the finished form. Workers no longer oversaw an object from beginning to end, nor did they necessarily understand its final appearance or use. The visible continuity between intention, effort, and result that had anchored craft meaning dissolved. Objects emerged from systems rather than individuals. For critics, this fragmentation of labor signaled a deeper fragmentation of creativity itself. If no single human mind shaped the whole, could the object still be said to embody intention?

The marketplace magnified these anxieties. Industrial goods flooded urban centers at unprecedented speed. Furniture, textiles, decorative objects, sheet music, and printed images poured into shops and homes. Middle-class interiors filled with patterned wallpaper, cast-iron ornament, and mass-produced furnishings that imitated earlier handcrafted styles. The sheer volume of objects made judgment difficult. Distinction blurred. When everything could be decorated, ornament seemed to lose its significance. Scale eroded the ability to read objects as markers of care, skill, or moral seriousness.

Standardization intensified the shock. Industrial processes prioritized consistency, efficiency, and repeatability. Identical forms appeared again and again, detached from locality or maker. For many Victorians, this repetition felt uncanny. Objects looked correct but felt interchangeable. Beauty appeared to float free of context, available everywhere and belonging nowhere. Critics worried that aesthetic experience was being flattened, reduced to surface effect without depth. Scale did not merely multiply objects. It multiplied sameness.

The speed of industrial production compounded the problem in ways that went beyond quantity alone. Where craft required time, machines compressed it, collapsing weeks or months of labor into moments of output. The temporal dimension of making disappeared from view. Objects arrived fully formed, stripped of visible process, as if they had emerged spontaneously rather than been worked into being. This invisibility fed suspicion. If effort could not be seen, could it be trusted? Victorians often equated speed with carelessness and ease with moral laxity. The shock of scale was therefore also a shock of tempo, a sense that the rhythm of industrial life had outrun inherited ideas about deliberation, patience, and value.

It was precisely this shock that made new forms of creativity unavoidable. Industrialization exposed the limits of older aesthetic frameworks that equated meaning with scarcity, locality, and visible labor. The problem was not that machines produced too much, but that society lacked the conceptual tools to interpret abundance without defaulting to despair. The flood of industrial objects forced critics, designers, and artists to confront a fundamental question: whether beauty could survive when it was no longer rare, slow, or traceable to a single hand. The answers would diverge sharply, but the question itself marked the beginning of a profound rethinking of creativity under modern conditions, one that would shape debates about art, labor, and meaning well into the twentieth century.

John Ruskin: Truth, Labor, and the Moral Failure of Machines

For John Ruskin, industrialization represented not merely an aesthetic problem but a moral catastrophe that reached into the foundations of social life. His critique of machine production was rooted in an ethical vision that bound beauty to truth, labor, and human suffering. Ruskin did not oppose technology in the abstract, nor did he indulge in simple nostalgia for a pre-industrial past. What he opposed was any system of production that severed the moral bond between the maker and the made, transforming human beings into instruments and objects into lies. In his view, art derived its value not from polish, regularity, or technical perfection, but from the visible presence of human effort, judgment, and limitation. The irregularity of handwork was not a defect. It was evidence of moral life. Machines threatened this presence by concealing labor, eliminating choice, and erasing the marks of individual struggle that Ruskin believed gave objects their ethical gravity.

Central to Ruskin’s thought was the concept of “truth to materials,” a principle that demanded honesty in both construction and appearance. Materials, he argued, should speak in their own voices, shaped by human hands that respected their limits and possibilities. Ornament, for Ruskin, was legitimate only when it grew organically from structure, material, and skilled labor rather than being mechanically applied or imitated. Industrial production violated this principle repeatedly. Cast ornament mimicked carved stone. Machine engraving simulated handwork. Painted surfaces concealed inferior materials beneath. Such imitation was not merely deceptive in a visual sense. It was morally corrosive because it presented the appearance of care without the reality of it. Ruskin feared that a culture surrounded by false ornament would lose its sensitivity to truth itself, becoming habituated to surfaces that looked right while meaning something else entirely.

Ruskin’s concern extended beyond objects to the condition of workers themselves. He viewed industrial labor as spiritually deadening, reducing human beings to extensions of machines rather than agents of judgment and creativity. Where craft demanded attention and allowed variation, factory work demanded obedience and repetition. This loss of creative agency, Ruskin argued, impoverished both the worker and the culture that consumed the resulting products. A society that accepted lifeless labor would inevitably accept lifeless beauty. The moral failure of machines lay not in their efficiency, but in their capacity to normalize work without meaning and production without dignity.

Ruskin’s critique was also aspirational rather than purely condemnatory. He believed that art could serve as a moral teacher, shaping habits of attention, care, and empathy. His opposition to machine-made ornament was inseparable from his broader social vision, one in which beauty cultivated ethical awareness rather than anesthetized it. While his prescriptions were often impractical and idealized, his diagnosis captured a genuine historical anxiety. The fear was not that machines would end art, but that they would train society to accept a form of beauty emptied of human consequence, a beauty that asked nothing of its makers or its viewers.

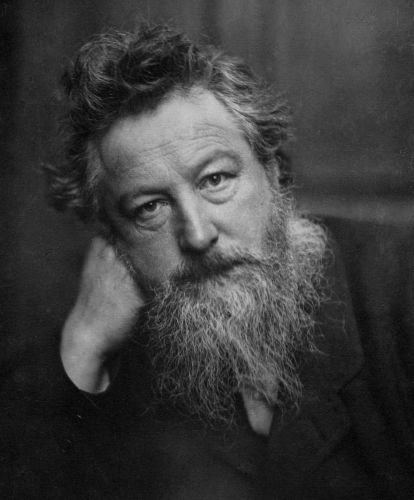

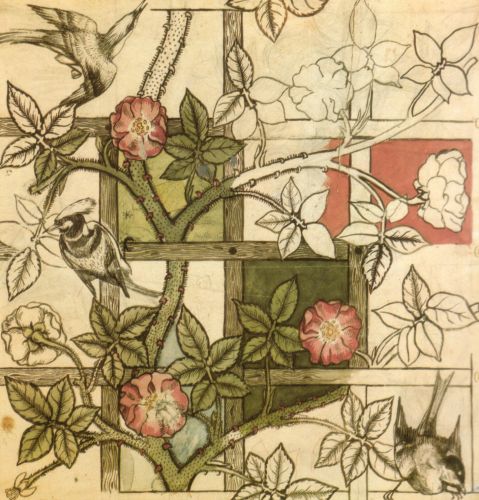

William Morris and the Politics of Craft

William Morris extended Ruskin’s moral critique of industrial production into an explicitly political vision. Where Ruskin diagnosed the ethical damage caused by mechanization, Morris sought its social remedy. He understood craft not simply as an aesthetic preference, but as a model for reorganizing labor, society, and everyday life. For Morris, the problem with industrial capitalism was not only that it produced ugly or deceptive objects, but that it alienated workers from the joy and meaning of their labor. Craft represented a form of work in which creativity, pleasure, and usefulness were reunited, restoring dignity to production and purpose to design.

Morris’s critique was inseparable from his socialism and from his conviction that economic structures shaped aesthetic outcomes. He argued that industrial labor reduced workers to instruments, stripping them of agency, imagination, and any meaningful connection to what they produced. Factory production prioritized speed, profit, and uniformity, encouraging indifference rather than care. Craft, by contrast, demanded judgment, variation, and attention to materials, allowing workers to see themselves reflected in their work. Morris believed that such labor cultivated pride, responsibility, and ethical awareness. A society organized around meaningful work would not merely produce better objects, but healthier social relations. Beauty, in his view, was a collective good rooted in shared labor, not a luxury commodity reserved for elites.

The Arts and Crafts movement that Morris helped inspire was therefore not a retreat into nostalgia, but an effort to articulate an alternative modernity grounded in ethical production. While it drew heavily on medieval forms and techniques, its ambitions were forward-looking rather than antiquarian. Morris did not deny the permanence of industrial society. He challenged its values. The movement emphasized honesty of materials, visible workmanship, and the reintegration of design and labor. At the same time, it exposed deep contradictions. Handmade goods were expensive and time-consuming. Craft production struggled to compete with industrial scale. Morris himself was acutely aware that the very market forces he opposed limited access to the objects his movement produced, creating a tension between egalitarian ideals and economic reality.

Despite these contradictions, Morris’s influence was enduring. His insistence that aesthetics could not be separated from labor, politics, and social justice reshaped debates about design well into the twentieth century. By framing craft as a site of resistance rather than mere taste, Morris shifted attention from surface appearance to underlying values. His work demonstrated that mechanization did not dictate a single cultural outcome. It created conditions under which societies were forced to choose. The politics of craft lay not in rejecting machines outright, but in insisting that any system of production be evaluated by the quality of human life it sustained.

The Fear of Soulless Beauty

By the mid-nineteenth century, Victorian criticism increasingly converged on a single, charged accusation: that industrial culture produced beauty without soul. This fear was not directed at ugliness or incompetence, but at objects that appeared aesthetically correct while feeling emotionally vacant. Machine-made ornament, mass-produced furniture, and standardized decorative arts were unsettling precisely because they succeeded on the surface. They satisfied the eye while provoking unease. Beauty, critics argued, had become detached from inner life, intention, and moral seriousness, reduced to appearance without depth.

Victorian writers often described this condition in moral and even spiritual terms. Objects were accused of being lifeless, mechanical, or false, not because they lacked complexity, but because they lacked an origin story rooted in human struggle. The handmade object bore traces of decision, error, fatigue, and adaptation. Its irregularities testified to a living process. The machine-made object, by contrast, concealed its making entirely. It arrived complete, polished, and mute. Without visible labor, critics feared that beauty had lost its ethical anchor. Pleasure could be consumed without responsibility, admiration without empathy for the conditions of production, and aesthetic enjoyment without any corresponding moral awareness.

This anxiety was intensified by imitation. Industrial ornament frequently borrowed the forms of earlier handcrafted traditions, reproducing Gothic tracery, classical motifs, and medieval patterns through casting and stamping. To Ruskinian critics, such imitation was not homage but deception. It simulated craft without embodying it, borrowing the authority of tradition while bypassing its discipline. The result was what they perceived as aesthetic dishonesty: forms that referenced meaning without participating in its creation. Soulless beauty was therefore not merely repetitive. It was derivative without commitment, repetition without memory, surface without responsibility.

Underlying these critiques was a fear about the human subject as much as about objects themselves. If people surrounded themselves with mechanical beauty, would their sensibilities become mechanical in turn? Victorians worried that habitual exposure to standardized ornament would dull moral perception, training individuals to accept appearances without inquiry. Beauty, once understood as a form of ethical education that sharpened attention and judgment, risked becoming anesthetic. It soothed rather than challenged. The concern was not that machines would eliminate taste, but that they would lower the threshold at which beauty demanded effort, reflection, or care from its audience.

Yet the fear of soulless beauty also revealed a profound paradox. It assumed that meaning resided permanently and exclusively in process rather than in use, interpretation, or context. Critics treated the machine as if it erased human presence entirely, overlooking the layers of intention embedded in design decisions, aesthetic choices, and acts of selection and consumption. This blind spot would become increasingly visible as new artistic movements emerged that embraced industrial methods while rejecting Victorian moral panic. The Victorian critique captured a genuine disruption in how beauty was made and perceived, but it mislocated the source of meaning itself. Beauty had not lost its soul. Its soul had migrated, awaiting new frameworks capable of recognizing human creativity under conditions of mechanization.

The Arts and Crafts Movement: Resistance through Redefinition

The Arts and Crafts movement emerged in the late nineteenth century as a direct response to the anxieties surrounding industrial production, but it was never a simple rejection of modernity or technology. Its leaders did not deny the permanence of machines, nor did they imagine a realistic return to pre-industrial craft economies. Instead, they sought to redefine the terms under which creativity, labor, and beauty could coexist with mechanization. The movement framed resistance not as retreat, but as ethical recalibration. It asked not whether machines should exist, but how their use should be disciplined by human values, social responsibility, and aesthetic integrity. In this sense, Arts and Crafts was less a backward-looking protest than an attempt to reclaim agency in a world increasingly shaped by industrial systems.

At the heart of the movement was a renewed emphasis on process. Arts and Crafts designers insisted that the manner of making mattered as much as the finished form. Visible workmanship, honest materials, and structural legibility became aesthetic principles. These were not merely stylistic preferences or nostalgic gestures. They were moral claims about the relationship between maker and object, and about the kinds of labor a society should reward. By foregrounding process, the movement sought to restore a sense of human presence that industrial production had rendered invisible. Beauty was reattached to labor, not through sentimentality, but through deliberate constraint and conscious refusal of deceptive ease.

The movement also redefined originality in ways that challenged dominant Victorian assumptions. In contrast to fears that repetition destroyed creativity, Arts and Crafts practitioners embraced tradition as a living, generative resource. Medieval and vernacular forms were not copied mechanically but reinterpreted through contemporary hands, materials, and needs. Pattern, repetition, and variation were treated as expressive rather than deadening, capable of conveying rhythm, intention, and continuity. Originality resided not in novelty for its own sake, but in thoughtful engagement with inherited forms. This stance directly opposed industrial culture’s fixation on speed and constant innovation, proposing instead a slower model of creativity grounded in memory, restraint, and interpretation.

Education played a central role in this redefinition. Arts and Crafts reformers emphasized training that integrated design and making, theory and practice. Art schools and workshops sought to dissolve the rigid division between artist and artisan that industrial systems had entrenched. Students were encouraged to understand materials through direct engagement rather than abstract planning alone. This pedagogical focus reinforced the movement’s broader argument: that creativity was neither spontaneous genius nor mechanical output, but a cultivated, embodied practice developed through time, discipline, and attention.

Yet the movement was never free from contradiction, and its leaders were often acutely aware of this fact. Arts and Crafts objects were labor-intensive and therefore expensive, placing them largely out of reach for the working-class consumers whose alienation the movement criticized. The emphasis on handcraft limited scalability and reinforced the very inequalities the movement sought to address. Morris himself openly acknowledged this tension, recognizing that ethical production within a capitalist economy involved unavoidable compromises. As a result, the Arts and Crafts movement functioned as critique as much as solution. It exposed the moral costs of industrial production even as it struggled to offer a fully inclusive alternative.

Despite these limitations, the Arts and Crafts movement achieved something enduring in the Victorian era. It shifted the cultural conversation by demonstrating that machines did not dictate values on their own. Creativity, it argued, was a matter of choice, intention, and organization rather than technological inevitability. The movement did not halt industrialization, but it profoundly influenced how later designers approached it. Its legacy is visible in modern design’s concern with function, honesty, material integrity, and user experience. Resistance through redefinition proved more powerful than outright rejection. It showed that creativity survives technological change not by denying new tools, but by redefining what it means to use them well.

Modern Design after Morris: Learning from the Machine

By the early twentieth century, a new generation of designers concluded that resistance alone was no longer sufficient. Industrialization had proven irreversible, and the moral critique articulated by Ruskin and Morris, while influential, could not fully address a world structured around machines, mass markets, and urban life. Modern design emerged from this recognition. Rather than treating mechanization as a moral failure to be endured or resisted, modernists approached it as a condition that demanded intellectual engagement. The central question shifted decisively: not how to preserve craft against machines, but how to design meaningfully within a machine-made world without surrendering ethical responsibility.

Modern designers therefore rejected the Victorian strategy of disguising machines as hands. The imitation of carved ornament or handcrafted irregularity, once intended to preserve moral legitimacy, came to be seen as dishonest. Instead, modernism emphasized truth of form and process. Ornament was stripped away not as an aesthetic purge, but as a philosophical stance. Objects should reveal how they were made and why they existed. A chair should look like a chair produced by industrial means, not a sentimental echo of pre-industrial labor. This approach reframed the machine from a source of shame into a source of clarity. Mechanization could be ethically legible if it was not asked to lie.

Institutions such as the Deutscher Werkbund and later the Bauhaus crystallized this shift. These movements accepted standardization as inevitable, but insisted that it be shaped by design intelligence rather than left to market forces alone. Mass production was reconceived as an opportunity to distribute well-designed objects broadly. The goal was coherence rather than uniqueness. Beauty moved away from visible labor and toward proportion, function, and clarity.

This reorientation required a further redefinition of originality. Modernism rejected both romantic craft nostalgia and decorative excess. Innovation was understood as problem-solving under constraint, balancing efficiency with human need and repetition with meaningful variation. Creativity relocated from expressive handwork to decisions about structure, scale, and use.

Modern design completed a transformation that Victorian critics could only anticipate. The machine ceased to function as a moral antagonist and became a medium through which ethical choices were articulated. Beauty was no longer judged by how visibly human its production appeared, but by how responsibly it served human life under modern conditions. By learning from the machine rather than fighting it, modern design demonstrated that mechanization did not end creativity. It clarified where creativity actually resided: in judgment, intention, and responsibility exercised at scale.

Machine Production and the Long History of Creative Panic

The Victorian response to industrial art was not unique. It belonged to a much longer historical pattern in which new modes of production repeatedly provoke fears about cultural decline. Whenever creative output becomes faster, cheaper, or more abundant, critics tend to interpret the change as evidence that meaning itself is under threat. Mechanization, in this sense, does not merely alter how objects are made. It destabilizes inherited assumptions about where value resides, triggering panic that is as much philosophical and moral as it is aesthetic.

These panics share a common structure. First comes the perception of excess: too many objects, images, or sounds circulating too quickly to be judged properly. This excess is then linked to repetition, which is read as the enemy of originality. Repetition suggests automation, formula, and loss of intention. From there follows a moral diagnosis. If art can be produced mechanically, critics argue, it must lack soul. Creativity becomes equated with scarcity, difficulty, and visible struggle. Anything that undermines those conditions appears suspect by definition, regardless of its actual cultural effect.

History offers numerous examples beyond the nineteenth century. The printing press was accused of flooding Europe with shallow texts and empowering unqualified authors. Photography was condemned for replacing artistic skill with mechanical capture. Recorded music was said to destroy live performance and musical discipline. Film and later television were accused of numbing audiences and degrading taste. In each case, the complaint was not that the new medium failed aesthetically, but that it succeeded too easily. The anxiety was always about effort made invisible and abundance made ordinary.

What these moments reveal is a persistent confusion between process and value. Critics often assume that creativity is located primarily in the difficulty of production rather than in the acts of selection, interpretation, and use that surround produced objects. When machines remove visible struggle, they appear to remove meaning itself. Yet meaning has never been guaranteed by effort alone. It emerges from cultural frameworks that assign significance, establish standards, and cultivate judgment over time. New technologies disrupt those frameworks abruptly, long before alternative systems of evaluation have had a chance to stabilize, creating the illusion that meaning has vanished rather than migrated.

Machine production intensifies this disruption by accelerating cultural feedback loops. Styles spread rapidly across markets. Imitation becomes immediately visible. Weak work proliferates alongside strong work without temporal separation. This simultaneity creates the impression that quality has collapsed, when in fact the range of quality has simply widened. Under conditions of scarcity, only a narrow slice of production survives to represent an era. Under conditions of abundance, everything appears at once. Panic arises because discernment must now do the work that exclusion once performed silently.

The long history of creative panic suggests that mechanization does not erode meaning by itself. Instead, it exposes the fragility of systems that relied on limitation rather than evaluation. Each technological shift forces a renegotiation of standards, institutions, and literacies. Those negotiations are rarely calm or orderly. They are marked by nostalgia, moral rhetoric, and predictions of collapse. But over time, cultures adapt. New criteria for value emerge that no longer depend on scarcity, visible labor, or difficulty of production alone. Meaning survives by reorganizing itself around judgment rather than gatekeeping.

Victorian fears about machine-made art were not irrational, but they were historically incomplete. They correctly identified a rupture without fully grasping its trajectory. Mechanization did not end creativity. It changed the conditions under which creativity had to justify itself, forcing new answers to old questions about intention, value, and purpose. The panic surrounding machine production belongs to a recurring cycle in cultural history: shock, denunciation, adaptation, and redefinition. Understanding that cycle matters, because it reveals that fear is not evidence of cultural decline, but a signal that creativity is being renegotiated under new conditions of possibility rather than extinguished.

Generative AI and the Return of the “Soulless” Critique

Contemporary criticism of generative artificial intelligence reproduces Victorian anxieties with remarkable fidelity. AI-generated images, music, and text are frequently described as technically proficient yet emotionally hollow. The complaint is rarely that the output fails aesthetically. It is that it feels wrong, as if something essential were missing. Like machine-made ornament in the nineteenth century, AI creations are accused of simulating creativity without embodying it. They look right, but they do not seem to mean. This language of soullessness echoes earlier fears that mechanized production severs form from intention and beauty from human presence.

Much of this critique rests on an assumption inherited from earlier creative panics: that meaning resides primarily in the act of making rather than in interpretation, use, or reception. Because generative models operate through pattern recognition and statistical recombination, critics argue that their outputs lack intention and therefore lack value. Yet this framing mirrors Victorian objections to industrial design, which treated the absence of visible labor as evidence of moral emptiness. In both cases, the machine becomes a stand-in for a deeper unease about authorship, agency, and control under conditions of abundance.

AI also intensifies anxieties about imitation in ways that closely resemble earlier technological shifts. Generative systems openly rely on existing styles, genres, and conventions, recombining them at scale and with unprecedented speed. This visibility makes imitation impossible to ignore. What had once been quietly accepted as part of human creativity becomes newly suspect when performed by machines. Critics worry that such systems reward formula, flatten difference, and accelerate aesthetic saturation, producing outputs that feel interchangeable and thin. Yet history suggests that imitation has never been the enemy of creativity. It has been its infrastructure. Traditions, genres, and schools of style depend on repetition, variation, and shared reference. What changes in the age of AI is not the presence of imitation, but its transparency and volume, which strip away comforting myths about originality while forcing a confrontation with how much creativity has always depended on patterned inheritance.

The “soullessness” critique of AI reflects a transitional moment rather than a settled judgment. As with industrial art, photography, and recorded sound, generative AI destabilizes inherited criteria for value before new ones have formed. The fear is not irrational. It identifies a real shift in how creativity is produced and recognized. But it mislocates meaning by tying it too tightly to process rather than judgment. If past technological transformations offer guidance, it is that creativity survives not by excluding machines, but by redefining what human intention, responsibility, and interpretation mean in relation to them.

Creativity after Mechanization: Constraints as Catalysts

Across historical moments of technological disruption, creativity has not vanished under mechanical constraint. It has reorganized itself around new limits. Mechanization narrows certain possibilities while opening others, forcing artists, writers, and designers to rethink where originality actually resides. When hand labor is no longer the primary site of value, creativity migrates to structure, concept, interpretation, and choice. Constraint becomes productive rather than prohibitive. It sharpens intention by reducing illusion.

This pattern is visible across multiple cultural domains in the modern period. In modernist design and architecture, the rejection of ornament forced attention onto proportion, material logic, and spatial clarity. In experimental music, limitations on tonality or instrumentation generated entirely new aesthetic languages. In literature, the disappearance of scarcity did not flatten creativity but intensified competition over voice, argument, and conceptual rigor. Constraint clarified stakes. It required creators to articulate why their work mattered rather than relying on tradition, difficulty, or exclusivity to confer value. Formal limits became engines of invention rather than signs of depletion.

Mechanization also reveals creativity to be fundamentally relational rather than purely individual. When production becomes easier and more abundant, meaning shifts toward context, framing, and interpretation. Creativity emerges not only in making new objects, but in selecting, recombining, and situating them within existing cultural fields. Curatorial judgment, audience awareness, and ethical responsibility grow in importance. This does not diminish originality. It reframes it. The creative act becomes less about producing something unprecedented in isolation and more about producing something purposeful, legible, and consequential within a dense ecosystem of signs and references.

Mechanization does not threaten creativity. It disciplines it. By removing certain forms of friction, it demands greater clarity of judgment and intention. The history of culture shows that creativity flourishes not in the absence of limits, but in negotiation with them. Constraints act as catalysts because they force creators to confront harder questions about meaning, responsibility, and use. What survives mechanization is not genius understood as spontaneity, but creativity understood as sustained, reflective choice under modern conditions.

Conclusion: Soul Was Never in the Tool

Across the long history traced here, moments of technological change repeatedly provoke the same fear: that creativity has been emptied of its human core. From scribal repetition to print, from industrial manufacture to recorded media, and now to generative AI, critics have returned to the language of loss, declaring that culture has become mechanical, derivative, or hollow. Yet this fear has always misidentified the source of meaning. The soul of creative work has never resided in the tool itself, whether chisel, press, factory, camera, or algorithm. It has resided in the human frameworks that shape how tools are used, constrained, interpreted, and judged. Technologies change the surface of culture, but they do not determine its depth. That depth emerges from intention, responsibility, and the standards societies choose to uphold.

Each technological shift disrupts inherited criteria for judgment before new ones have time to stabilize. In those unsettled moments, abundance masquerades as decline and repetition is mistaken for emptiness. What disappears is not creativity itself, but the comfort of familiar markers such as visible labor, scarcity, and difficulty. When those shortcuts fail, cultures are forced into a more demanding position: evaluating meaning without relying on mystique or exclusion.

History shows that creativity survives by relocating itself rather than by resisting change outright. Craft yields to design. Ornament gives way to structure. Authorship expands into curation, interpretation, and ethical responsibility. These shifts do not erase human agency. They refine it. New tools constrain certain gestures while expanding others, compelling creators to articulate intention more clearly and audiences to cultivate judgment more actively. Creativity persists not because tools are limited, but because human choice remains irreducible.

The recurring panic over soullessness ultimately reveals less about machines than about human uncertainty during periods of transition. Fear arises when familiar hierarchies collapse and when meaning must be rebuilt rather than inherited. The lesson of history is not that creativity must be protected from tools, but that it must be continually redefined alongside them. Soul was never in the tool. It was always in the standards we defend, the responsibilities we accept, and the choices we make when new capacities force us to decide what creativity is for.

Bibliography

- Adamson, Glenn. The Invention of Craft. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

- Banham, Reyner. Theory and Design in the First Machine Age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960.

- Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots.” Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (2021).

- Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken, 1935.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

- Droste, Magdalena. Bauhaus, 1919–1933. Cologne: Taschen, 1990.

- Eco, Umberto. The Open Work. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962.

- Edwards, Clive. Turning Houses into Homes: A History of the Retailing and Consumption of Domestic Furnishings. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005.

- Epstein, Steven A. Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Frayling, Christopher. The Royal College of Art: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Art and Design. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1987.

- Giedion, Sigfried. Mechanization Takes Command. New York: Oxford University Press, 1948.

- Gombrich, E. H. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960.

- Harrod, Tanya. The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Hewison, Robert. John Ruskin: The Argument of the Eye. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976.

- Hilton, Tim. John Ruskin: The Later Years. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Hobsbawm, Eric. Industry and Empire. London: Penguin, 1969.

- Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Kozbelt, Aaron. “The Aesthetic Legacy of Evolution: The History of the Arts as a Window Into Human Nature.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:787238 (2012).

- MacCarthy, Fiona. William Morris: A Life for Our Time. London: Faber & Faber, 1994.

- Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

- Morris, William. Art and Socialism. London: George Bell & Sons, 1884.

- —-. Useful Work versus Useless Toil. London: Commonweal, 1885.

- Naylor, Gillian. The Arts and Crafts Movement: A Study of Its Sources, Ideals, and Influence on Design Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1971.

- Onion, Rebecca. “Reclaiming the Machine:An Introductory Look at Steampunk in Everyday Practice.” Neo-Victorian Studies 1:1 (2008): 138-163.

- Ruskin, John. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1849.

- —-. The Stones of Venice. Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1853.

- Sennett, Richard. The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Sussman, Herbert. “Machine Dreams: The Culture of Technology.” Victorian Literature and Culture 28:1 (2000): 197-204.

- Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. London: Victor Gollancz, 1963.

- —-. William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary. New York: Pantheon, 1955.

- Whitford, Frank. Bauhaus. London: Thames & Hudson, 1984.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.27.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.