A civic order that relies on compulsory symbolic participation sacrifices trust for control and silence for peace.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Instruction Becomes Enforcement

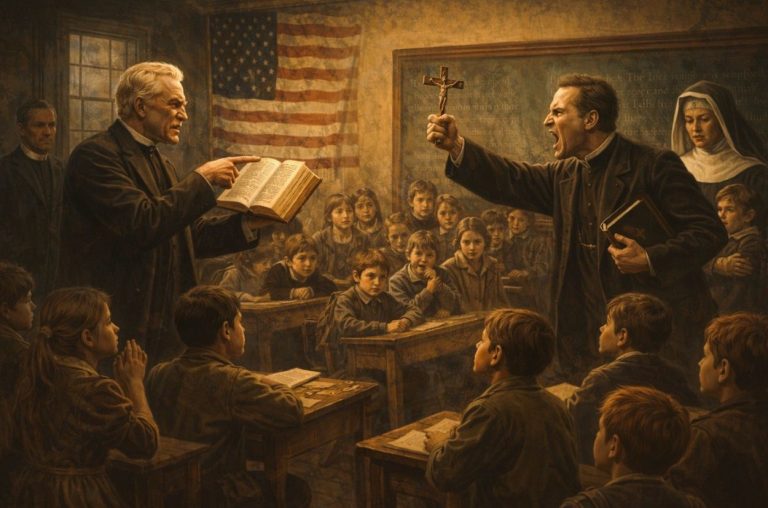

States have long recognized education as one of the most effective instruments for shaping social order. Instruction does more than transmit information or cultivate skills. It establishes norms, encodes authority, and teaches individuals how to interpret their place within a political community. Because education operates early and continuously, it is uniquely suited to producing habits of compliance that feel natural rather than imposed. When governments mandate religious education, they often frame it as moral formation, cultural inheritance, or civic cohesion. Yet once instruction is backed by law rather than persuasion, it ceases to function as education in any meaningful sense. It becomes enforcement. What is taught matters less than the fact that participation is compulsory, monitored, and backed by the threat of sanction. At that point, instruction no longer seeks understanding. It seeks alignment.

Visigothic Spain in the seventh century offers a stark example of this transformation. The Fourth Council of Toledo in 633 CE formalized an unprecedented alliance between church and state, requiring Christian instruction for all subjects, including Jewish communities that had previously retained limited autonomy. This was not a missionary project aimed at conversion through argument or example. It was a legal regime designed to impose religious uniformity through compulsory teaching. Instruction became a mechanism of surveillance and control, ensuring that religious difference could no longer exist outside the reach of state authority.

The shift from tolerance to coercion was justified as a matter of stability. Visigothic rulers and bishops assumed that religious uniformity would eliminate social friction and consolidate political loyalty. Education appeared to offer a humane alternative to violence, a way to shape belief without overt force. In practice, however, compulsory instruction functioned as a form of soft coercion backed by legal threat. Parents hid children. Families feigned compliance. Communities fractured or fled. The state mistook exposure for conviction and presence for assent, confusing the performance of learning with genuine belief.

This pattern has broader implications beyond its medieval context. The Visigothic case reveals a recurring error in political reasoning: the belief that shared instruction produces shared values. When religious education is enforced, it does not create unity. It teaches citizens which beliefs are officially acceptable and which are suspect, and it does so under the authority of law rather than consent. Dissent becomes evidence of disloyalty rather than conscience, and refusal is recast as social deviance rather than moral integrity. The Fourth Council of Toledo stands as an early warning about the dangers of legislating belief through pedagogy. Education imposed to enforce religious conformity does not stabilize society. It destabilizes it by converting moral difference into a problem of obedience, a lesson with enduring relevance for any state tempted to mistake compulsory instruction for social cohesion.

Visigothic Spain before Toledo: Conditional Pluralism

Before the Fourth Council, Visigothic Spain was characterized by a fragile but functional form of religious pluralism. Jewish communities had lived on the Iberian Peninsula for centuries, predating Visigothic rule and surviving the transition from Roman administration to Gothic kingship. While Jews were socially marginalized and subject to periodic restrictions, they retained a degree of legal recognition and communal autonomy. This tolerance was neither egalitarian nor principled. It was conditional, pragmatic, and rooted in political calculation rather than commitment to religious freedom.

Visigothic rulers initially understood pluralism as manageable so long as it remained socially contained and politically nonthreatening. Jewish communities were permitted to maintain their religious practices, internal governance, and educational traditions, provided they did not challenge royal authority or Christian dominance in public life. The state’s concern was less with belief than with order, taxation, and predictable obedience. Religious difference was tolerated as a legacy condition rather than embraced as a civic good. As long as minority communities remained legible, regulated, and quiet, their existence posed no immediate problem. This arrangement reflected a broader late antique pattern in which rulers tolerated difference not as a right but as a concession, one that could be withdrawn if circumstances demanded greater uniformity.

Yet this conditional pluralism rested on unstable foundations. It depended heavily on political circumstances, episcopal influence, and the personal priorities of individual kings. Periods of relative tolerance were punctuated by moments of repression, particularly when rulers sought closer alignment with ecclesiastical authority or faced internal challenges to legitimacy. Religious difference became a convenient site for asserting control, especially when uniformity could be framed as a solution to disorder. Pluralism survived only so long as it did not conflict with evolving notions of Christian kingship.

By the early seventh century, this balance had begun to erode in visible and consequential ways. The conversion of the Visigothic monarchy from Arianism to Nicene Christianity intensified pressures for religious conformity across the realm and strengthened the alliance between royal power and episcopal authority. Jewish difference, once tolerated as a legacy of Roman pluralism, increasingly appeared as an anomaly within a self-consciously Christian state that defined itself through orthodoxy. Legal restrictions multiplied, rhetoric hardened, and religious education began to emerge as a tool of correction rather than coexistence. The stage was set for Toledo. What had been managed through conditional tolerance would soon be recast as a problem demanding resolution, not accommodation. The Fourth Council did not invent coercion, but it codified a transition already underway, transforming pragmatic coexistence into enforced conformity.

The Fourth Council of Toledo: Church and State Align

The Fourth Council of Toledo, convened in 633 CE, marked a decisive turning point in the relationship between religious authority and royal power in Visigothic Spain. Presided over by Isidore of Seville, the council brought together bishops and royal representatives in a forum that blurred any remaining distinction between ecclesiastical deliberation and state policy. What emerged was not merely a set of doctrinal clarifications but a comprehensive vision of Christian kingship in which political unity and religious conformity were inseparable. The council did not simply advise the crown. It legislated alongside it.

This alignment was rooted in the political anxieties of the Visigothic elite. The kingdom faced internal instability, contested successions, and the lingering memory of religious division following the monarchy’s earlier adherence to Arian Christianity. Orthodoxy offered a language of consolidation. By binding royal legitimacy to Nicene Christianity, rulers sought to stabilize authority through shared religious identity. The council’s decrees reflect this logic. Unity was no longer a matter of pragmatic coexistence but a moral imperative, one that could be enforced through law with ecclesiastical justification.

The most consequential feature of the council’s legislation was its treatment of religious difference as a political problem requiring correction. Jewish communities, long tolerated under conditional pluralism, were now positioned as obstacles to unity rather than manageable minorities. The council reaffirmed and expanded earlier anti-Jewish measures, framing coercive policies as acts of pastoral responsibility and civic necessity. Religious difference was no longer something to be regulated at the margins but something to be actively transformed. The language of salvation and correction masked a deeper shift in governance. Religious instruction was elevated from a pastoral practice to an administrative instrument, tasked with reshaping identity rather than cultivating belief. In this framework, deviation was not simply error but a failure of social alignment demanding intervention.

Crucially, the council did not rely on persuasion as its primary mechanism. It authorized the use of legal compulsion to ensure Christian instruction, including the mandatory education of Jewish children in Christian doctrine. This move redefined the purpose of teaching itself. Instruction was no longer oriented toward understanding or conversion through conviction. It was designed to produce conformity through exposure, repetition, and institutional oversight. The presence of the child within Christian instructional structures mattered more than the internalization of belief. Education became a site where the state could reach beyond adult consent and intervene directly in the formation of identity, extending coercion into the intimate domain of family and upbringing.

The fusion of church and state authority at Toledo also reconfigured the meaning of obedience. Compliance with religious instruction was framed as loyalty to the realm, while resistance was cast as defiance not only of ecclesiastical authority but of royal law. This convergence eliminated the possibility of principled neutrality. One could no longer obey the king while dissenting from mandated religious education. The council collapsed these domains into a single obligation, transforming religious nonconformity into civic disobedience.

In this way, the Fourth Council of Toledo formalized a model of governance that equated uniformity with stability and instruction with control. The alliance it forged was powerful but brittle. By substituting legal coercion for persuasion, it undermined the very legitimacy it sought to secure. The council’s confidence in its authority produced short-term compliance at the cost of long-term cohesion. Resistance did not disappear; it adapted through concealment, evasion, and flight. Families fractured, trust eroded, and loyalty became conditional rather than genuine. The decrees of Toledo reveal a state increasingly unwilling to tolerate difference and increasingly convinced of its right to reshape belief through law. What followed was not the unity promised by enforced orthodoxy, but a legacy of instability that later rulers would inherit rather than resolve.

Religious Education as Law, Not Teaching

The decrees of the Fourth Council transformed religious education from a pastoral practice into a legal mandate with binding civic force. Instruction in Christian doctrine was no longer framed as an invitation to belief, moral reasoning, or spiritual formation guided by persuasion. It became an obligation enforced jointly by ecclesiastical authority and royal law. Education ceased to operate as a communicative or dialogical act and instead functioned as an extension of governance. To be taught was no longer a choice or a relational process but a condition of lawful belonging within the Visigothic polity. In this framework, instruction did not aim to cultivate understanding. It aimed to secure compliance.

This shift altered the purpose of instruction itself. Teaching was no longer oriented toward dialogue, comprehension, or internal assent. Its function was exposure. By requiring attendance, repetition, and familiarity with Christian doctrine, the state sought to render religious difference unsustainable. The assumption was not that belief would emerge organically through conviction but that sustained contact with authorized teaching would dissolve resistance through normalization. In this model, the content of instruction mattered less than the inevitability of participation. Education became a tool for reshaping identity through endurance rather than persuasion.

Legal enforcement ensured that refusal could not remain private or contained within the family. Parents who resisted compulsory instruction for their children faced penalties, surveillance, and the gradual erosion of parental authority. The state positioned itself as a superior moral guardian, entitled to intervene where families were judged religiously deficient or socially suspect. This intrusion extended governance into the most intimate domains of upbringing and belief formation. Education became inseparable from monitoring. Learning environments doubled as sites of assessment, where conformity could be observed, recorded, and enforced. The classroom ceased to be a space for moral formation and became an arena in which obedience was rehearsed and evaluated.

The use of education as law also reconfigured the meaning of conversion. Conversion ceased to signify an inward transformation of belief and instead became indistinguishable from procedural compliance. To attend instruction, recite doctrine, or submit children to Christian teaching was treated as sufficient evidence of alignment, regardless of internal conviction. This emphasis on outward behavior allowed authorities to claim success while obscuring the persistence of dissent. Education functioned as a statistical solution to religious difference, producing measurable participation without resolving underlying opposition.

In this sense, compulsory religious education failed as teaching but succeeded as control. It produced compliance without loyalty and familiarity without trust. Rather than integrating minority communities, it deepened alienation by signaling that difference would be corrected rather than accommodated. The Visigothic state mistook exposure for persuasion and legality for legitimacy. By turning education into law, it stripped instruction of its formative capacity and transformed it into a blunt instrument of authority. What emerged was not shared belief but managed obedience, sustained by fear, surveillance, and the constant threat of sanction rather than by conviction or consent.

Families, Fear, and Concealment

The enforcement of compulsory Christian instruction reshaped daily life within Jewish communities in Visigothic Spain in ways that extended far beyond formal religious practice. Education policy reached directly into the household, transforming families into sites of anxiety and strategic calculation. Parents were no longer simply responsible for transmitting tradition. They were forced to navigate a legal environment in which their authority over children was conditional and vulnerable to state intervention. The home, once a relatively protected space of religious continuity, became exposed to surveillance and suspicion.

Fear structured parental behavior under this regime in pervasive and enduring ways. Sources indicate that families adopted strategies designed not to resist openly but to avoid detection and minimize harm. Children were hidden during periods of inspection or compulsory instruction. Attendance was falsified where possible. Outward compliance masked inward refusal, creating a dual reality in which public conformity coexisted with private preservation. These acts were not expressions of political defiance but survival strategies shaped by asymmetrical power. Parents sought to protect children from compulsory instruction that threatened communal identity while avoiding punishment that could include confiscation of property, loss of custody, or exile. The psychological toll of constant vigilance and calculation reshaped family life, teaching children early that safety depended on silence and careful performance.

This pressure fractured familial relationships as well as communal trust. Parents were forced to weigh the risks of resistance against the dangers of compliance, choices that carried long-term consequences for children raised between conflicting authorities. The state’s intrusion into education undermined parental legitimacy, casting families as potential sources of disorder rather than guardians of moral formation. Within communities, fear of informants and inconsistent enforcement eroded solidarity. Concealment required secrecy, and secrecy weakened collective life even as it preserved identity.

Flight emerged as another response to enforced instruction. For some families, concealment was insufficient or unsustainable. Migration offered an escape from compulsory education, even at the cost of economic hardship and social dislocation. This movement destabilized local economies and disrupted networks that had previously facilitated coexistence. What the state framed as corrective policy produced demographic instability. Instead of integrating minority populations, it accelerated their displacement.

These outcomes reveal the social cost of using education as a tool of coercion. Compulsory instruction did not reshape belief. It reshaped behavior through fear, surveillance, and strategic compliance. Families learned to perform conformity while guarding identity through secrecy, deception, or departure. The state succeeded in making religious difference administratively inconvenient but failed to eliminate it. In doing so, it undermined trust between rulers and subjects and within communities themselves. Education imposed through law fractured the very social fabric it was intended to unify, replacing shared civic life with suspicion and quiet resistance.

Coercion without Conversion

The policies enacted after the Fourth Council of Toledo reveal a fundamental miscalculation at the heart of forced religious education. Compulsory instruction succeeded in increasing outward conformity but failed to produce genuine conversion. Attendance at Christian teaching, recitation of doctrine, and participation in sanctioned rituals created the appearance of alignment without transforming belief. The state conflated visibility with conviction, mistaking participation for assent. What emerged was not a unified religious community but a population adept at performing compliance under pressure.

This distinction mattered because belief, unlike behavior, cannot be compelled by law. Conversion requires persuasion, trust, and voluntary commitment, conditions fundamentally incompatible with coercion. Forced instruction bypassed dialogue entirely, replacing moral engagement with obligation. Rather than drawing communities toward Christianity, compulsory education trained individuals to associate Christian teaching with surveillance, punishment, and loss of autonomy. For Jewish communities in particular, mandated exposure to Christian doctrine reinforced communal boundaries rather than dissolving them. Christianity appeared not as a persuasive moral framework but as the religion of power, backed by the authority of the state. The more insistently instruction was imposed, the more clearly it signaled domination rather than invitation, deepening resistance rather than eroding it.

The gap between compliance and conviction produced a brittle form of religious uniformity. Authorities could point to participation rates and instructional reach as evidence of success, yet these metrics concealed widespread concealment and inward refusal. Outward conformity became a survival skill rather than a sign of loyalty. This dynamic eroded trust between rulers and subjects, as the state relied increasingly on surveillance and repetition to sustain the appearance of unity. Coercion generated the need for further coercion, locking governance into a cycle of enforcement without resolution.

In this sense, compulsory religious education achieved the opposite of its stated aims. It did not integrate minority communities into a shared moral order or cultivate genuine allegiance to Christian authority. Instead, it taught communities how to comply without consenting and how to preserve identity under constraint. Conversion without consent proved illusory, and uniformity without conviction proved unstable. The Visigothic experience demonstrates that belief shaped by fear does not endure. When education functions as law rather than dialogue, it produces obedience without allegiance, conformity without trust, and a fragile social order dependent on continual pressure rather than shared commitment.

The State’s Miscalculation: Uniformity as Stability

Visigothic authorities operated under a powerful but flawed assumption: that religious uniformity would produce political stability. In a kingdom marked by recent conversion, internal factionalism, and fragile royal legitimacy, shared Christian identity appeared to offer a solution to disorder. Uniform belief promised predictability. If all subjects were instructed in the same doctrine, educated within the same moral framework, and publicly aligned with the same religious authority, loyalty might follow. This logic treated difference as a source of instability and sameness as a safeguard against fragmentation.

What this reasoning failed to account for was the difference between imposed alignment and voluntary cohesion. Uniformity achieved through law does not eliminate disagreement. It suppresses its visibility. By forcing religious education and ritual performance, the Visigothic state reduced the public expression of difference while intensifying its private significance. Communities did not abandon identity under pressure. They guarded it more carefully, embedding belief within family structures, informal networks, and practices of concealment. Stability was achieved only at the level of appearances, while beneath the surface resentment, fear, and mistrust accumulated. The state mistook silence for agreement and absence of protest for consent, misunderstanding the social costs of enforced sameness.

This miscalculation also distorted the state’s understanding of loyalty. Compliance was interpreted as consent, and participation as belief. Yet loyalty rooted in coercion is contingent and brittle. It depends on continued enforcement rather than shared commitment. The Visigothic regime mistook administrative control for legitimacy, assuming that conformity signaled integration. In reality, it produced subjects skilled at navigating power without trusting it. Uniformity became a mask for alienation rather than a foundation for cohesion.

The long-term consequences of this error were profound and enduring. Policies designed to stabilize the realm instead generated instability that later rulers inherited rather than resolved. Forced instruction fractured families, disrupted local economies through flight, and corroded confidence in both church and crown. Religious authority became associated with punishment rather than moral guidance, while royal law came to be feared rather than respected. Rather than consolidating authority, coercive uniformity weakened it by eroding the moral credibility of governance itself. The Visigothic case demonstrates a recurring historical lesson: stability cannot be engineered by erasing difference. When states equate unity with sameness, they sacrifice trust for control and mistake silence for peace.

Education as Boundary-Making

The policies enacted in Visigothic Spain reveal that education functioned less as a means of transmitting knowledge than as a mechanism for drawing and enforcing social boundaries. Compulsory Christian instruction did not simply communicate doctrine or moral guidance. It operated as a classificatory system, sorting populations according to their proximity to state-sanctioned identity. Education marked who belonged fully within the political community and who occupied a conditional, surveilled, or suspect status. By embedding this sorting process in routine instruction, the state transformed learning into a quiet test of alignment. Inclusion and exclusion were no longer declared openly. They were enacted daily through attendance, compliance, and visibility within educational spaces.

This boundary-making function depended fundamentally on the compulsory nature of participation. When instruction is voluntary, education can coexist with pluralism and disagreement. When it is mandatory, it becomes an instrument of differentiation. Attendance, recitation, and submission to authorized teaching signal acceptance of the state’s symbolic order regardless of inner belief. Those who complied passed without notice, absorbed into the category of normal subjects. Those who hesitated, resisted, or required coercion were rendered legible as outsiders in need of correction. Education translated abstract religious difference into observable behavior, allowing authorities to classify and manage populations without directly interrogating conscience. The classroom became a site where belonging was quietly adjudicated, and where neutrality was impossible precisely because participation itself carried political meaning.

For minority communities, this process clarified the limits of tolerance. Compulsory instruction communicated not only what was to be learned but which identities were considered incomplete or deficient. The state did not need to declare Jews enemies of the realm. It merely positioned them as targets of correction. Education served as a civilizing project aimed at reshaping identity rather than accommodating difference. The message was unmistakable: full belonging required conformity, and education was the instrument through which conformity would be achieved.

The Visigothic case underscores a broader political lesson. Education always carries boundary-making power, even when framed as neutral or benevolent. When states mandate religious instruction, they teach more than doctrine. They teach which beliefs are acceptable, which identities are provisional, and which forms of dissent will be tolerated only temporarily. Education, under these conditions, becomes a quiet but potent tool of exclusion. It does not eliminate difference. It organizes it, marking the lines along which social trust, loyalty, and legitimacy will ultimately fracture.

From Toledo to the Classroom

The legacy of the Fourth Council of Toledo does not end with the collapse of Visigothic rule. Its significance lies in the governing logic it made explicit: the use of compulsory education to enforce symbolic conformity while denying that belief itself is being regulated. The form has changed, but the structure remains recognizable. Where Visigothic authorities mandated Christian instruction through ecclesiastical law, modern states often mandate exposure to religious narratives through ostensibly secular institutions. The language is no longer salvation or orthodoxy but heritage, tradition, or civic literacy. What persists is the assumption that enforced instruction can stabilize identity and produce cohesion.

This continuity is most visible in contemporary debates over mandated scripture reading or religiously inflected curricula in public schools. Proponents frequently insist that such material is presented for historical, moral, or cultural reasons rather than devotional ones. Students are not asked to believe, only to learn. This distinction mirrors the Visigothic separation between belief and participation, where instruction was framed as corrective exposure rather than conversion. Yet, as in Toledo, the separation collapses under scrutiny. Mandatory engagement still communicates hierarchy. It signals which narratives are foundational, which traditions define the civic core, and which identities are expected to adapt. Even when framed as neutral literacy, compulsory instruction conveys normative judgments about belonging that cannot be disentangled from power.

The classroom, like the Visigothic instructional system, becomes a site where belonging is quietly negotiated. Participation is compulsory, alternatives are limited, and refusal carries social or administrative cost. Students who object are not framed as exercising conscience but as disrupting education, tradition, or unity. The mechanism is familiar. Dissent is reclassified as inconvenience. Resistance is pathologized as misunderstanding. The state maintains that it is not enforcing belief, even as it enforces symbolic participation that marks religious difference as deviation.

What distinguishes modern contexts is the presence of constitutional protections and pluralistic ideals that explicitly reject religious coercion. Yet these protections are often weakened when religious material is reframed as cultural inheritance rather than belief. This rhetorical move allows the state to bypass safeguards designed to protect conscience by redefining the terrain on which coercion operates. As in Visigothic Spain, the effect is not the elimination of difference but its reorganization. Minority identities are tolerated only insofar as they do not resist symbolic incorporation into dominant narratives. Objection becomes framed as rejection of shared culture rather than as defense of pluralism, narrowing the space for legitimate dissent within institutions ostensibly committed to inclusion.

The lesson of Toledo is not that education should avoid religion entirely, but that coercion disguised as instruction undermines both education and civic trust. Mandated scripture reading does not create shared values. It teaches students which beliefs are officially acceptable and which must remain private or defensive. The Visigothic state believed it could secure unity by compelling instruction. Instead, it revealed the limits of authority over belief. Modern classrooms face the same risk when education becomes a tool for signaling conformity rather than cultivating understanding. History suggests that such efforts do not produce cohesion. They produce quiet fracture, managed compliance, and enduring resentment beneath the surface of apparent order.

Conclusion: The Cost of Teaching by Command

The Fourth Council of Toledo stands as a clear historical warning about the limits of authority over belief. By transforming religious education into a legal mandate, the Visigothic state attempted to solve political insecurity through instructional force. What it achieved instead was a brittle order sustained by fear, concealment, and outward compliance. Education, stripped of persuasion and dialogue, became an instrument of control rather than formation. The appearance of unity masked deep fractures that policy could neither heal nor permanently suppress.

Across the Visigothic case, a consistent pattern emerges. Compulsory instruction did not erase difference; it reorganized it. Families adapted through secrecy, performance, and flight. Communities hardened identities rather than relinquishing them. The state mistook participation for consent and exposure for conviction, relying on measurable compliance while ignoring the erosion of trust that accompanied it. Teaching by command replaced moral authority with administrative power, undermining the very legitimacy the regime sought to secure.

This historical lesson extends well beyond medieval Spain. Whenever states mandate religious instruction under the guise of culture, heritage, or civic literacy, they repeat the same structural error. Education becomes a boundary-making device rather than a space for understanding, sorting populations instead of cultivating judgment. Dissent is misread as disloyalty, and refusal is reframed as hostility to shared values rather than an assertion of conscience. In such systems, pluralism survives only as long as it remains quiet and compliant. What is taught matters less than what participation signals: which beliefs are officially acceptable, which identities are provisional, and which forms of difference will be tolerated only until they become visible.

The cost of teaching by command is not merely ethical but political. A civic order that relies on compulsory symbolic participation sacrifices trust for control and silence for peace. The Visigothic experience demonstrates that belief cannot be legislated into existence and that education cannot substitute for legitimacy. Durable unity requires institutions capable of accommodating visible moral difference without coercion or suspicion. When instruction becomes enforcement, cohesion gives way to fracture, and authority learns too late that obedience is no substitute for loyalty. History’s warning is unambiguous: unity imposed through education is always fragile, and the moment conscience insists on being seen, it begins to fail.

Bibliography

- Apple, Michael W. Ideology and Curriculum. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 1979.

- Bachrach, Bernard S. Early Medieval Jewish Policy in Western Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977.

- Collins, Roger. Early Medieval Spain: Unity in Diversity, 400–1000. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

- —-. Law, Culture, and Regionalism in Early Medieval Spain. Aldershot: Variorum, 1992.

- —-. Visigothic Spain, 409–711. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

- Fletcher, Richard. The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. New York: Henry Holt, 1997.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1977.

- Fraser, James W. Between Church and State: Religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- Hillgarth, J. N. The Visigoths in History and Legend. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2009.

- Moore, R. I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

- —-. “The Weight of Opinion: Religion and the People of Europe from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century.” In Making Early Medieval Societies, edited by Kate Cooper and Conrad Leyser, 91–110. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Panzram, Sabine. The Visigothic Kingdom: The Negotiation of Power in Post-Roman lberia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

- Sullivan, Winnifred Fallers. The Impossibility of Religious Freedom. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Thompson, E. A. The Goths in Spain. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

- Vives, José, ed. Concilios Visigóticos e Hispano-Romanos. Barcelona: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1963.

- Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Wood, Jamie. The Politics of Identity in Visigothic Spain: Religion and Power in the Histories of Isidore of Seville. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.06.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.