The medieval Christian animalization of Jews and Muslims was a learned way of seeing, cultivated through institutions that claimed moral authority.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Seeing as Believing

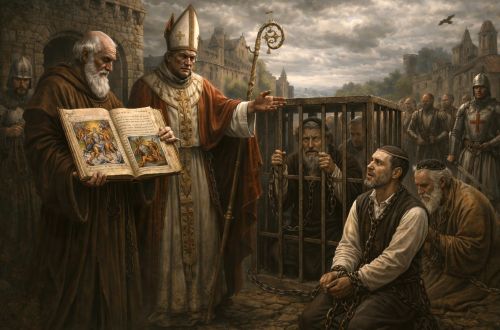

Medieval dehumanization did not rely primarily on spontaneous hatred or popular rumor. It was taught. Across Christian Europe, institutions shaped moral perception through images, stories, and repeated visual cues that instructed audiences how to interpret the human world. In this context, seeing was not passive observation but moral formation. What believers learned to see determined what they learned to tolerate, exclude, or punish. Dehumanization functioned less as an eruption of violence than as a gradual education of perception.

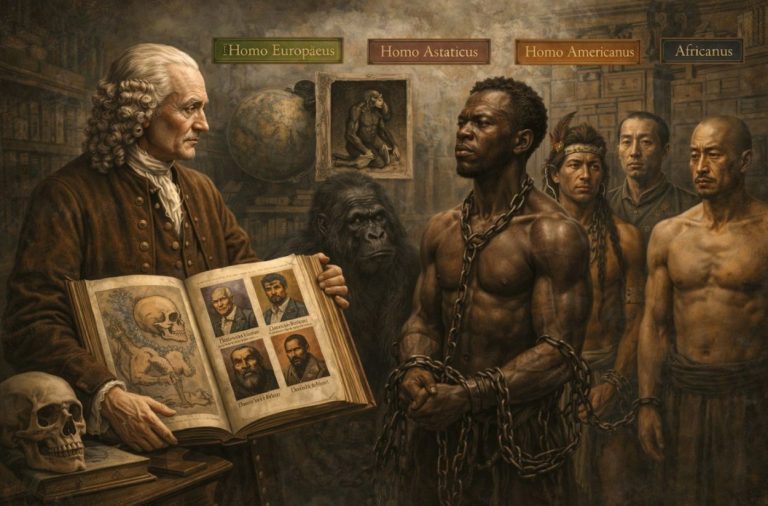

Medieval Christian bestiaries, sermons, and ecclesiastical imagery operated as a coordinated pedagogical system that normalized the animalization of Jews and Muslims over centuries. These representations were not marginal expressions of prejudice, nor were they confined to moments of crisis or popular unrest. They were produced by clerics, copied by monastic scriptoria, displayed in churches, and reinforced through preaching. In this way, animalization was embedded in the ordinary rhythms of Christian instruction. By placing minorities within a symbolic animal hierarchy already familiar to audiences, church institutions reframed exclusion as spiritual clarity rather than injustice. Violence, segregation, and legal discrimination did not need to be justified as exceptional measures. They appeared instead as the natural consequences of moral discernment properly applied.

Bestiaries played a central role in this process, functioning as authoritative guides to moral interpretation rather than as decorative or entertaining compilations. These texts taught readers how to read the created world as a moral text authored by God. Animals were assigned stable meanings. Reason was opposed to appetite. Order was contrasted with chaos, restraint with excess. When Jews and Muslims were depicted as pigs, dogs, apes, or lust driven beasts, these images did more than demean. They instructed viewers to understand certain populations as governed by bodily impulse rather than rational control. In doing so, bestiaries translated theological judgments into visual form, making claims about moral incapacity appear self-evident. The animal image became a lesson in who could be trusted with reason, law, and authority, and who could not.

The power of this system lay in its respectability. Images and sermons did not incite rage so much as cultivate certainty. Repetition trained the imagination until animalization felt obvious rather than imposed. Once perception was shaped, cruelty required no further argument. Exclusion could be experienced as protection, segregation as purity, and violence as cleansing. What follows examines visual racism as institutional pedagogy, showing how Christian Europe learned to see minorities as beasts, and how that vision transformed persecution into moral duty.

Bestiaries as Theology: Animals, Allegory, and Moral Order

Medieval bestiaries were not marginal or whimsical texts. They functioned as theological instruments designed to teach Christians how to interpret the world morally. Drawing on earlier sources such as the Physiologus, bestiaries presented the natural world as a divinely authored text in which every creature carried ethical meaning. Animals were not studied for their biological accuracy but for their symbolic value. To read a bestiary was to learn how God’s moral order was inscribed into creation itself, visible to those properly instructed in allegory.

Animals were assigned stable moral characteristics that mirrored Christian ethical categories. Lions signified Christ and rightful authority. Lambs represented innocence and sacrifice. Serpents embodied deception. Appetite, excess, cunning, and irrationality were mapped consistently onto particular creatures, creating a moral taxonomy that readers were trained to recognize instantly. These meanings were reinforced through repetition across manuscripts, sermons, and visual art, ensuring that allegorical associations became second nature rather than interpretive choices.

Bestiaries offered a theology of order grounded in hierarchy, one that extended seamlessly from the animal kingdom into human society. Just as animals were ranked according to their moral qualities, so too were humans implicitly ranked according to their proximity to reason, restraint, and spiritual discipline. Rational control was treated as the defining mark of moral worth, while bodily appetite and instinct signaled ethical deficiency. This framework did not need to name human groups explicitly in order to shape perception. By habituating readers to think in graded moral categories, bestiaries established a symbolic grammar through which audiences learned to associate virtue with rational mastery and vice with animality. The moral hierarchy of beasts quietly prepared the ground for the moral hierarchy of people.

This moral grammar blurred the boundary between human and animal categories. Because animals were already moralized, depicting a human group in animal form did not merely insult them. It made a claim about their ethical nature. When a figure was shown with animal traits or associated visually with beasts, viewers were invited to understand that figure as governed by appetite rather than reason. The image carried theological authority because it drew on a symbolic system already validated by scripture, tradition, and clerical teaching.

The authority of bestiaries was amplified by their institutional context and modes of circulation. They were copied by monks, preserved in monastic libraries, and owned by ecclesiastical institutions that controlled theological education. Clergy drew upon their imagery in sermons, translating visual allegory into spoken moral instruction. Illuminations extended their reach beyond literacy, allowing allegorical lessons to be absorbed visually by lay audiences who may never have encountered the text itself. In this way, bestiaries operated at the intersection of text, image, and preaching, reinforcing a unified moral worldview in which hierarchy appeared divinely sanctioned, coherent, and visually self-evident across multiple settings.

By the time Jews and Muslims were inserted into this symbolic system, the work of moral preparation had already been completed. Bestiaries had trained Christian audiences to see appetite as moral danger, animality as ethical failure, and hierarchy as the proper structure of a well-ordered world. The theological function of animal allegory made it possible to translate complex religious, cultural, and political hostilities into simple visual truths that required no explanation. Dehumanization, in this context, did not rely on argument or persuasion. It relied on a shared moral vocabulary that rendered certain conclusions obvious before they were ever articulated, allowing exclusion and hostility to feel like recognition rather than invention.

Animalizing the Other: Jews, Muslims, and the Logic of Appetite

Within the moral framework established by bestiaries, Jews and Muslims were not depicted as merely different, mistaken, or heretical. They were positioned as morally other in a far more fundamental sense, defined by an alleged domination of appetite over reason. Medieval Christian imagery repeatedly associated Jews with pigs, dogs, apes, and other animals understood to be driven by instinct, filth, or imitation rather than rational judgment. Muslims, often labeled collectively as Saracens, were portrayed as beasts ruled by lust, excess, and violence. These representations did not function as casual insults. They asserted a claim about moral incapacity, placing entire populations outside the bounds of disciplined rationality that defined Christian virtue.

The logic at work here was not random symbolism but systematic moral classification. In bestiary thought, appetite represented danger because it signified a failure of internal hierarchy. Reason was meant to rule the body just as Christ ruled the faithful. To be governed by desire was to be unfit for self-governance. By assigning Jews and Muslims to animal categories associated with gluttony, lust, or cunning, Christian imagery transformed religious difference into a problem of nature rather than belief. Conversion alone could not resolve this condition, because the deficiency was depicted as embedded in bodily and moral disposition rather than doctrinal error.

Jews were often animalized in ways that emphasized proximity and contamination. Pigs and dogs were familiar creatures within Christian society, associated with filth, scavenging, and improper boundaries. To depict Jews in these forms was to present them as internal pollutants rather than external enemies. This imagery supported segregation, legal restriction, and episodic violence by framing Jewish presence as a threat to communal purity. The animal image suggested that exclusion was not persecution but sanitation, a necessary measure to protect the moral health of the Christian body.

Muslims, by contrast, were more frequently animalized through imagery emphasizing uncontrolled appetite, sexuality, and aggression, often framed through exoticism and monstrosity. Medieval Christian art and sermons depicted Muslims as hybrid beasts, demonic figures, or men overwhelmed by lust and violence, lacking the rational restraint that defined Christian moral order. This imagery aligned closely with crusading ideology, which cast conflict as a struggle between rational Christian civilization and bestial infidelity. By portraying Muslims as incapable of restraint or deliberation, Christian institutions framed conquest, domination, and warfare as defensive or corrective acts rather than aggression. Violence could be imagined as necessary containment of chaos, morally justified by the alleged nature of the enemy rather than by political ambition or material gain.

What ultimately unites these depictions is the centrality of appetite as the marker of exclusion and moral inferiority. Whether portrayed as filthy scavengers within Christian society or as lust driven beasts beyond its borders, Jews and Muslims were represented as governed by the body rather than the mind. This framing did not deny their humanity outright. Instead, it placed them on a graded moral hierarchy, closer to animals than to fully rational Christians. Dehumanization operated here through classification rather than negation. By teaching audiences to associate certain populations with appetitive excess, Christian institutions transformed discrimination, segregation, and violence into reasonable responses to moral disorder. Cruelty did not need to be named as such, because it was experienced as discipline, purification, and defense of a divinely ordered world.

Visual Racism as Institutional Pedagogy

The animalization of Jews and Muslims did not circulate as isolated imagery, sporadic caricature, or expressions of popular hostility alone. It functioned as a coherent pedagogical system embedded within Christian institutions that shaped how believers learned to see the social and moral world. Illuminated manuscripts, church sculpture, stained glass, marginalia, liturgical objects, and sermons worked together to reinforce a shared visual vocabulary over generations. These images were encountered repeatedly and in authoritative settings: churches, monasteries, pilgrimage sites, and instructional texts. They were not framed as controversial statements or polemical arguments, but as ordinary components of religious education. Visual racism, in this sense, was not accidental, excessive, or peripheral. It was institutionalized as a method of moral instruction, teaching Christians how to recognize virtue and vice through sight itself.

This pedagogy relied on repetition rather than argument. Images trained perception long before explicit reasoning was required. By encountering Jews and Muslims consistently depicted in animalized forms, viewers learned to associate certain bodies with disorder, appetite, and moral danger without conscious reflection. The image did the work silently. It did not need to persuade. It only needed to be seen often enough to feel obvious. In this way, visual dehumanization bypassed debate and implanted itself as common sense, shaping instinctive responses rather than articulated beliefs.

Sermons reinforced this visual training by translating imagery into moral narrative and doctrinal explanation. Preachers drew upon familiar animal symbolism to explain sin, temptation, purity, and threat, embedding visual associations into spoken instruction. Congregations did not merely hear about moral hierarchy. They saw it in their surroundings, recognized it from repeated exposure, and were reminded of it through language that echoed the imagery surrounding them. This convergence of sight and speech created a closed interpretive loop. What was seen confirmed what was heard, and what was heard disciplined how future images would be interpreted. Visual racism became self-reinforcing, sustained through the alignment of art, theology, and preaching.

The institutional authority behind this system was decisive. Because the church controlled both theological education and much of the visual environment of medieval life, its imagery carried legitimacy rather than suspicion. Animalization was not presented as hatred or hostility, but as instruction, discernment, and spiritual clarity. Exclusion appeared as insight rather than bias. By shaping perception at the level of vision itself, Christian institutions ensured that discrimination, segregation, and violence could later be experienced as moral responses rather than political or ethical choices. Visual racism functioned as pedagogy precisely because it taught believers not what to argue, but how to see, and once vision was trained, cruelty no longer required justification.

Moral Hygiene: From Image to Law and Violence

The pedagogical force of visual animalization did not remain confined to imagination or belief. It translated into concrete social practices by reframing exclusion as moral hygiene. Once Jews and Muslims were understood as sources of disorder, appetite, or contamination, their regulation could be experienced not as persecution but as maintenance of communal health. The language of purity and pollution transformed political decisions into moral necessities. Law and violence did not appear as instruments of domination, but as tools for preserving the integrity of the Christian social body.

Legal discrimination drew heavily on this logic and expanded it into the routines of everyday governance. Restrictions on residence, occupation, clothing, and movement were justified as safeguards against moral and spiritual danger rather than as acts of punishment. Jews were segregated into specific quarters, barred from certain professions, restricted in their interactions with Christians, and marked visually through badges or mandated clothing. These measures were framed as preventative rather than punitive, designed to limit moral contamination rather than to inflict harm. The prior work of visual animalization ensured that such laws felt prudent and necessary. Because the targets of regulation had already been depicted as morally disordered, legal exclusion appeared as common sense administration rather than as injustice.

Violence followed a similar pattern of moral translation. Pogroms, expulsions, and forced conversions were rarely justified as acts of cruelty for their own sake. They were framed instead as necessary responses to provocation, impurity, or threat. When Jews were depicted as pigs or dogs, their suffering could be interpreted as the removal of filth rather than harm inflicted upon persons. Violence acquired a cleansing function. It appeared as the restoration of order rather than its violation, made thinkable and tolerable by the prior work of dehumanizing imagery.

Muslims were subjected to parallel logic on a broader geopolitical and theological scale. Crusading violence relied heavily on representations of Muslims as bestial, lust driven, or demonic adversaries whose very existence threatened Christian order. Such imagery allowed warfare to be imagined as moral purification rather than conquest or expansion. Killing, enslavement, and dispossession could be framed as defensive acts undertaken to contain chaos and preserve sacred order. As with internal minorities, violence against Muslims was represented not as aggression but as protection, justified by the alleged nature of the enemy rather than by political ambition, economic interest, or territorial desire.

Violence did not require constant incitement or emotional frenzy. Once visual pedagogy had trained perception, the threshold for cruelty was dramatically lowered. Lawmakers, clerics, and laypeople alike could participate in exclusion, expulsion, or violence while maintaining a sense of moral righteousness and spiritual duty. Ordinary actions such as enforcing regulations, closing gates, seizing property, or turning away neighbors could be experienced as acts of responsibility rather than harm. The victims of these actions were no longer encountered primarily as neighbors, traders, or fellow inhabitants with recognizable claims to dignity. They had already been repositioned within a symbolic order that rendered their suffering secondary to the preservation of purity, order, and Christian identity. This moral distancing allowed cruelty to be distributed across institutions and individuals without requiring anyone to perceive themselves as cruel.

Moral hygiene functioned as the bridge between image and action. Visual racism prepared the imagination. Law codified the distinctions it taught. Violence enforced the boundaries when law proved insufficient. At no point did the system need to acknowledge itself as persecution. It operated instead through the conviction that order required maintenance and that maintenance sometimes demanded removal. In this way, medieval Christian society learned to experience cruelty as care, exclusion as protection, and violence as moral necessity.

Conclusion: When the Church Taught Europe How to See

The medieval Christian animalization of Jews and Muslims was a learned way of seeing, cultivated through institutions that claimed moral authority over both belief and perception. Bestiaries, sermons, and sacred images did not merely reflect existing prejudices. They trained Christians to interpret human difference through a visual theology that equated reason with virtue and appetite with danger. By the time discrimination or violence occurred, the moral groundwork had already been laid. Exclusion felt intelligible. Cruelty felt corrective.

What distinguishes this system is its respectability. Dehumanization did not arrive as rage or panic but as instruction. The church taught Europe how to read the world, and in doing so, it taught believers whom to fear, whom to exclude, and whom to discipline. Visual racism operated quietly, forming instinct rather than argument. Once perception itself was shaped, law and violence required no elaborate justification. They appeared as natural responses to disorder rather than as deliberate acts of harm. Authority did not need to persuade. It had already taught its audience how to see.

This history matters because it reveals how deeply moral vision can be structured by power and how easily that structuring can be mistaken for spiritual insight. When institutions control the symbolic environment, they can transform contingent political decisions into moral necessities and ethical failures into matters of purification. The medieval church did not need to invent cruelty or command it directly. It needed only to provide a framework in which cruelty could be misrecognized as care and exclusion as responsibility. By embedding hierarchy in theology, image, and pedagogy, it ensured that persecution could be carried out by ordinary people who understood themselves as acting rationally, dutifully, even piously. The most consequential violence did not require fanatics. It required disciplined perception and moral certainty.

The lesson is not confined to the medieval past, nor to explicitly religious institutions. Whenever authority claims the power to shape perception itself, to define what is visible as order and what is visible as threat, the same logic reappears. Images and narratives that associate particular groups with disorder, appetite, or danger do not merely express bias. They train judgment in advance of action. Violence need not announce itself as violence when it can be experienced as protection, maintenance, or moral clarity. To recognize this is not to deny the power of images, but to take that power seriously and critically. When the church taught Europe how to see, it also taught Europe whom it was permitted to harm, how that harm could be justified, and why it could feel not only acceptable, but righteous.

Bibliography

- Belting, Hans. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- Bildhauer, Bettina. “Medieval European Conceptions of Blood: Truth and Human Integrity.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (2013), S57-S76.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Zone Books, 2011.

- Camille, Michael. The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- —-. Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Chazan, Robert. Medieval Stereotypes and Modern Antisemitism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Cohen, Jeremy. Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Freedberg, David. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Hassig, Debra. Medieval Bestiaries: Text, Image, Ideology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- —-. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Moore, R. I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

- Nirenberg, David. Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

- —-. Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Pluskowski, Aleks. “The Zooarchaeology of Medieval ‘Christendom’: Ideology, the Treatment of Animals and the Making of Medieval Europe.” World Archaeology 42:2 (2010), 201-214.

- Resnick, Irven M. “Odo of Tournai and the Dehumanization of Medieval Jews: A Reexamination.” The Jewish Quarterly Review 98:4 (2008), 471-484.

- Schmitt, Natalie Crohn. “The Idea of a Person in Medieval Morality Plays.” Comparative Drama 12:1 (1978), 23-34.

- Strickland, Debra Higgs. Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- White, T. H. The Book of Beasts. New York: Dover Publications, 1954.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.10.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.