In 1943, a propagandistic ideal meant creating a modern Ukraine through Soviet industrialization, even as the republic lay in ruins.

By Dr. Martin Blackwell

Professor of History

University of North Georgia

Only a few months after Kyiv as retaken from the Nazis in November 1943, the returning Stalinists started avoiding public mention of what had happened at places like Babyn Yar. The anti-Semitism that had emerged in the resource-starved Soviet rear may have been the reason for hushing up the fate of Soviet Jews under the Nazis—a conclusion bolstered by a study of wartime Tashkent where many Jewish evacuees lived.[1] At the same time, the Stalin regime’s wartime approval of Ukrainian nationalism to spur support for the Soviet cause was curtailed as the Kremlin encountered resistance to its return in Western Ukraine.[2]

Perhaps the Communists who returned to Kyiv now asked themselves how continually reminding people about the fate of thousands of Jews—and Ukrainians for that matter—during the occupation might help them create a more quiescent city, especially given the nature of the capital’s resettlement and the reassembly of its population?

The latter considerations form the focus of my recent book.[3] But part of my book also covers the ensuing attempts by the Ukrainian Communists to re-legitimize Soviet power in Kyiv after the Nazis. My conclusion was that Soviet power in the mid-1940s manifested itself as overwhelmingly male leaders who were meant to project the confidence that they could modernize the Ukrainian capital faster and better than anyone else.

Nikita Khrushchev’s role in this process was crucial. Soon after the Ukrainian Communists’ return, he ordered the city’s prewar general plan be revamped.[4]

A comment made by Zinovii Serdiuk—then the First Secretary of the Kyiv Oblast’ Party Committee—at the first post-occupation meeting of the city’s party cadre in December 1943 highlighted the then Ukrainian leader’s vision for the city’s future:

[Khrushchev] said Kyiv is the capital of Ukraine, the cultural center of Ukraine, and here there should be enterprises of exact mechanics. Here there should be optical tool and photo camera factories, and a radio factory…. Here we need factories of light industry, shoe factories, [and] a factory for the production of bicycles.[5]

Already in 1943, this propagandistic ideal meant creating a modern Ukraine through Soviet industrialization, even as the republic lay in ruins. The effort to reassert Kyiv as the cultural center of Soviet Ukraine would begin with the destroyed Khreshchatyk and Kalinin Square (as the Maidan was then called) which lay at its heart.

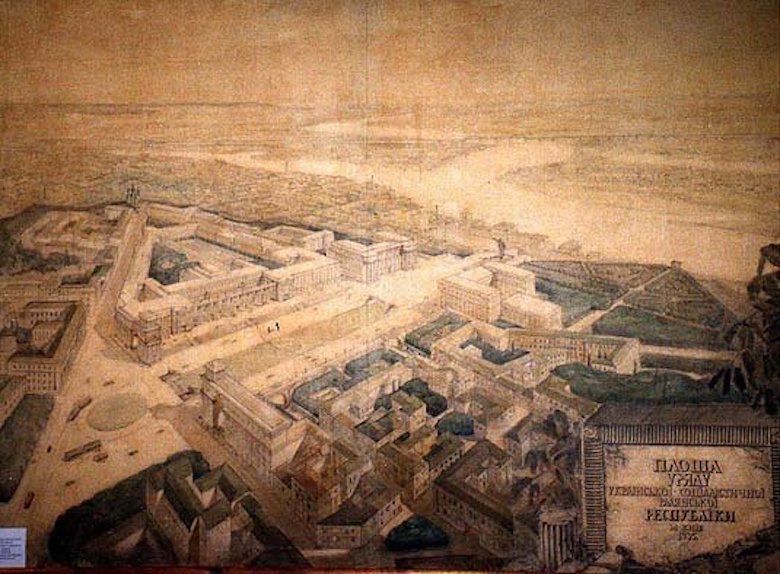

Khrushchev quickly changed the city’s general plan to accommodate his vision of the Khreshchatyk. Completion of the 1930s-era “Government Square,” located alongside the Ukrainian Central Committee’s headquarters on space where the destroyed Mykhailivs’kyi Monastery once stood, high above the Dnipro, was now scrapped completely.[6]

According to an Ivan Ihnatkin (writing in 1948),

One of the insufficiencies in the planning of old Kyiv was the absence of a big central square… [But] after the occupation, the question of the architectural completion of the ‘Government Square’ was posed in a completely different way. By a Ukrainian Council of People’s Commissars’ (SNK UkrSSR) directive, the central government square now lay immediately on the Khreshchatyk, the main artery of the city of Kyiv.[7]

A June 22, 1944, resolution of the same council mandated the drawing up of a preliminary project for the city center. It envisioned the main street “as a trade-business and civic-cultural center as well as a center for mass demonstrations, strolling, and the concentration and division of the traffic of the local and transitory mass transit.”[8]

From the beginning then, the returning Communists imagined that the Khreshchatyk’s reconstruction would prove to the population that Soviet power meant there would be leaders who knew how to lead. But, ideally, these Communists also wanted to show that they understood the thirst of the populace for a successful path to a modernized future.

I should add that the famous clearing of the Khreshchatyk was beginning before any of these plans were made. When Kyiv’s leadership first met regarding the street on February 8, 1944, according to Fedir Mokiyenko—then the Chairman of the Kyiv City Soviet—they set May 1, 1944 as the target date for finishing the clearing. “It is really beneficial for us to do as much as we can before May 1,” Mokiyenko stated at the meeting. “First, that is how long the workers can be mobilized. Second, because . . . in winter, we can take workers from the oblast while in summer they are occupied there with field work.”[9]

Serdiuk, who was there as well, then added another reason for starting this process in the dead of winter:

Work on the Khreshchatyk should be humming along, such that people see that they [the Ukrainian party members] have started to sort things out. And if they have started to sort things out, that means they are going to build.[10]

Many of Kyiv’s denizens would already, of course, have associated forced-paced modernization with Soviet power, and that previous association may have helped the return of these Communists.

Perhaps Serdiuk’s above belief was stirred by recollections like those voiced at a July 1944 Kyiv City Committee (Mis’kom) plenum by the Secretary Myronov of Petriv [later Podil] District Committee (Raikom):

On November 22 [1943], the people saw a beaten-up tram on the rails in Petriv District. . . . It was like people were seeing a tram for the first time. And after seeing it they declared, ‘Look, real bosses have actually arrived. Ours have arrived. Soviet power has arrived.’[11]

In the popular imagination, the post-occupation notion of Soviet power now implied men who were both “real bosses” and “ours,” and it was probably another reason why the Ukrainian Communists wanted to start reconstruction in a hurry.

Speaking at a second meeting about the Khreshchatyk on March 9, 1944, Mokiyenko then rationalized why Kyiv’s Communists hoped to draw ordinary Kyivans into this effort.

Noting the work of the conscript labor-staffed Special Construction Montage Unit no. 305 on the capital’s main artery, Mokiyenko stated, “They have no [labor] power. There, people do not work and do not have the enthusiasm that we have.”[12] To ensure that the Kyivan civilians who voluntarily mobilized for narodne budivnytstvo [people’s construction] remained enthusiastic, Mokiyenko urged better record-keeping of individuals’ work, payment for work actually accomplished, and assurance from the city’s district committees that the loading and unloading of debris continued on pace.

By July 7, 1944, however, a Kyiv City Committee’s resolution noted that the city district leading the way in clearing its area of the Khreshchatyk had fulfilled only 82 percent of the plan.

In their conclusion about why work on this project should accelerate, the resolution’s authors optimistically declared,

Every Kyivan, male and female . . . will put forth all their effort toward exhibiting new levels of self-sacrificial and highly productive labor in order to quickly finish the construction of the Khreshchatyk—the beauty, the glory, and the national pride of the great Ukrainian people.[13]

The effort to rebuild the Khreshchatyk had become the Kyivan Communists’ explicit answer to matters such as the Ukrainian insurgency to the city’s west.

But the reconstruction of the capital would be delayed due to lack of attention from the all-powerful Kremlin and the resulting lack of resources allocated to the city. Mobilizations of labor occurred but only enough to make sure Kyiv had enough firewood to survive the cold winter ahead.

As a result, the party relied on architectural visions of Kyiv’s future to re-legitimize Soviet power’s return.

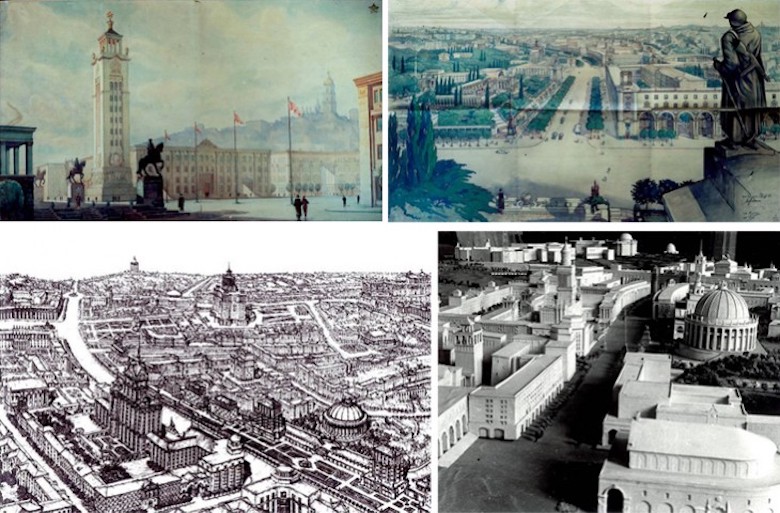

After the June 22, 1944 resolution mentioned above, dozens of architects and engineers competed to determine what a future Khreshchatyk would look like. Before the SNK UkrSSR declared a winner on March 8, 1945, some of their drawings were publicly displayed at the city’s Museum of Russian Art. According to the Kyivs’ka Pravda edition of January 9, 1945, more than a thousand Kyivans went to see these drawings, three of which the newspaper published over the following week.

Each of the published drawings is elaborate. All of them now portray Kalinin Square without the pre-revolutionary City Duma building that had dominated the area before the war. In the first two (depicted below), the square is surrounded by large Greek-columned government buildings, huge arches, and large monuments celebrating the liberation of the city.[14]

In the third (below), an even taller set of columned buildings completely surrounds a space that its planners now renamed “Victory Square” with a monument portraying a man on horseback at its center and endless rows of soldiers marching through it.[15]

Another newspaper, Trud na Kreshchatike (Labor on the Khreshchatyk), published a different drawing—found today in TsDAVOVU—from the exhibition on January 26, 1945.[16] There the scene looks away from the now-open space occupied by the former City Duma building across the Khreshchatyk and toward the formidable hill on the opposite side of the street that climbs toward the city’s elite Lypky District.

At the base of the hill is a huge hall said to seat five thousand people. Behind it, on the hill itself, is a pantheon with a massive statue of Stalin on top. A wide and curved set of steps from the theater still located on the Khreshchatyk today and to the hall’s right leads up to the pantheon.

On March 8, 1945, the Ukrainian Council of People’s Commissars resolved that two teams of architects would examine these projects and present their ideas to the Council’s Directorate of Artistic Affairs for the compilation of a new resolution by October 1, 1945.[17] The city’s chief architect, Oleksandr Vlasov, led one of these teams. In the introduction to his project, he argued that the Khreshchatyk buildings should “represent the greatness of the Stalinist epoch and its victories over fascism, reflect the Stalinist care for the individual through the modern conveniences found in its new buildings, and become an organic part of the general plan for the city’s future.”[18]

Another document of Vlasov’s contains his conclusions about the aims for this project:

The architecture of the Stalinist epoch should forever reflect the power and the greatness of the Soviet people, the fullness of its creative victories, and the eternal glory of the people-victor. One of these monuments to this historic epoch will be the newly reborn center of the city of Kyiv, the Khreshchatyk, and those regions around it destroyed by the German occupiers.[19]

Vlasov’s writings reflect the vague substance of the Ukrainian Communists’ legitimizing agenda during this period. Labeling the Khreshchatyk a symbol of the “victorious Stalinist epoch” meant applying the same modernizing vision to the downtown that had been the Ukrainian Communists’ last-ditch mantra since their return.

The other project—found today in Kyiv’s Central State Archive of Civil Organizations (TsDAHOU)—belonged to architect Oleksiy Tatsiy. Like Vlasov’s work, a smooth 500-meter long curve connecting the two straight sections of the Khreshchatyk was meant to replace the jagged one that had been there before.[20]

Tatsiy’s project (a successor to his 1944 original pictured below) featured a new Kyiv City Soviet building placed directly where today’s Ukraina Hotel now stands, complete with a Lenin monument tribune in front of it for viewing parades.

More spectacularly, the project also entailed the installation of escalators to glide up the steep Kirov Hill (present-day Mykhailo Hrushevs’kyi Street), the digging of three new tunnels—two from the new center down to Podil, and one from Besarabs’kyi Market at the Khreshchatyk’s far end up to Lypky—to ease the movement of trucks through the city center, and the construction of new buildings on the old “Government Square”.[21]

Perhaps Tatsiy’s overambitious ideas were the reasons why the Ukrainian republic’s new Council of Ministers declared Vlasov’s plan victorious on September 17, 1946, and ordered him to create a mock-up for the public at the Museum of Russian Art by February 1947.[22] The rare image at bottom right may reflect the development of Vlasov’s thinking for the entire street as seen from Besarabs’ka Square.

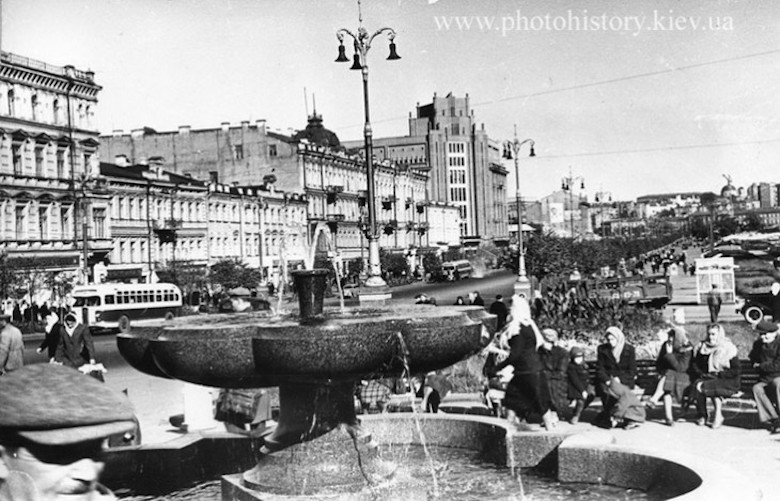

These efforts, though, should be contrasted with the modest achievements on the Khreshchatyk that I cover elsewhere in my book. Underneath the city’s main drag, a 1,200-meter “collector” for the laying of communal services was completed during these first years after the occupation. Up above, the asphalting of the 50-meter-wide road and two 14-meter-wide sidewalks was finished, and trees and temporary light posts were also installed by fall 1945.23 The picture below gives one a good idea of how the mid-1940s Khreshchatyk turned out.

It would be another five years before the main street’s rebuilding began. Moscow continued to withhold labor and other scarce resources from the city. The future Maidan remained as Kalinin Square. And perhaps even fewer Kyivans wanted to be reminded about the war. But the stumbling effort chronicled here to at least associate the returning Ukrainian Communists with modernization did eventually succeed in transforming Kyiv’s center into the airy late-socialist space it is now remembered as.

Notes

- Rebecca Manley, To the Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 230–33.

- Serhy Yekelchyk, Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 145–46.

- Martin J. Blackwell, Kyiv as Regime City: The Return of Soviet Power after Nazi Occupation (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2016), chapter 5.

- A. O. Matushevych, Khreshchatyk. (Kyiv: Vydavnytsvo Akademii Arkhitektury Ukrains’koi RSR 1950), 72.

- Derzhavnyi Arkhiv Kyivs’koi Oblasti (DAKO), p-1/3/2, fol. 57.

- Editor’s note: The Soviets closed down the monastery already in 1922, the removal of frescoes and mosaics inside the Mykhailvs’kyi Cathedral began in 1933, and the buildings were destroyed in 1934-37 (the bell tower, the cathedral itself, and the buildings of the former monastery). The project of the government center foresaw the erection of twin buildings on two sides of the Mykhailvs’kyi Square, only one of which was actually built (occupied by the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party and located on the site of the 12th century Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs (St. Basil’s Church) that was destroyed to make space for the building). Today, the large and heavy building that overwhelms the Dnipro hill—a typical example of Stalinist architecture—is occupied by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of independent Ukraine. In the 1930s, the reconstruction plan envisioned for the government of the Soviet Ukrainian Republic to be housed in the twin building where the Mykhailivs’kyi Cathedral stood.

- Ivan A. Ignatkin, Kyiv (Moskva: Izdatel’stvo Akademii Arkhitektury SSSR, 1948), 16–18.

- Matushevych, 15.

- In the last work of the Soviet era published on Kyiv’s history, V. P. Smishko admitted the city’s rebirth after the war “by enthusiasm alone” was not possible. See his Vozrozhdennyi Kiev: Trudovoe sodruzhestvo narodov SSSR v vosstanovlenii stolitsy Ukrainy, 1943-1950 gg. (Kyiv: Vyshcha Shkola, 1990), 59–60.

- DAKO, p-1/3/45, fols. 66, 67.

- DAKO, p-1/3/23, fol. 92.

- DAKO, p-1/3/45, fol. 104.

- DAKO, p-1/3/32, fol. 20.

- Kyivs’ka Pravda, 9 January 1945, p. 2; 12 January 1945, p. 1.

- Apparently this was before Kyiv’s current “Victory Square” was created on the space known before the Second World War as the “Jewish Bazaar” or Evbaz. Kyivs’ka Pravda, 14 January 1945, p. 1.

- Tsentral’nyi Derzhavnyi Arkhiv Vyshchykh Orhaniv Vlady Ukrainy (TsDAVOVU), r-2/7/1949, fol. 97.

- Matushevych, Khreshchatyk, 92.

- TsDAVOVU, r-2/7/1949, fols. 21, 22

- TsDAVOVU, r-2/7/1950, fol. 38. The Khreshchatyk was blown up by Stalin’s NKVD after the Germans arrived in the city in September 1941. The resulting fires destroyed other nearby neighborhoods in the hours and days that followed. The arriving Nazis lost many men due to the explosions and let the fires burn themselves out. The Nazis used the explosions as the pretext to execute the city’s “resistance” to the occupation, focusing primarily on its Jewish population: in the last two days of September alone, over 33,000 Jewish Kyivans were massacred at Babyn Yar; a total of over 100,000 Kyivans of all ethnicities and patients of local mental hospitals were executed there by the end of the occupation.

- Tsentral’nyi Derzhavyni Arkhiv Hromads’kykh Obied’nan Ukrainy (TsDAHOU), 1/23/1921, fols. 1, 2.

- Matushevych, Khreshchatyk, 93.

- TsDAHOU, 1/23/1921, fols. 3, 7.

- TsDAHOU, 1/23/1921, fol. 19.

Originally published by Krytyka, (July 2018) republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.