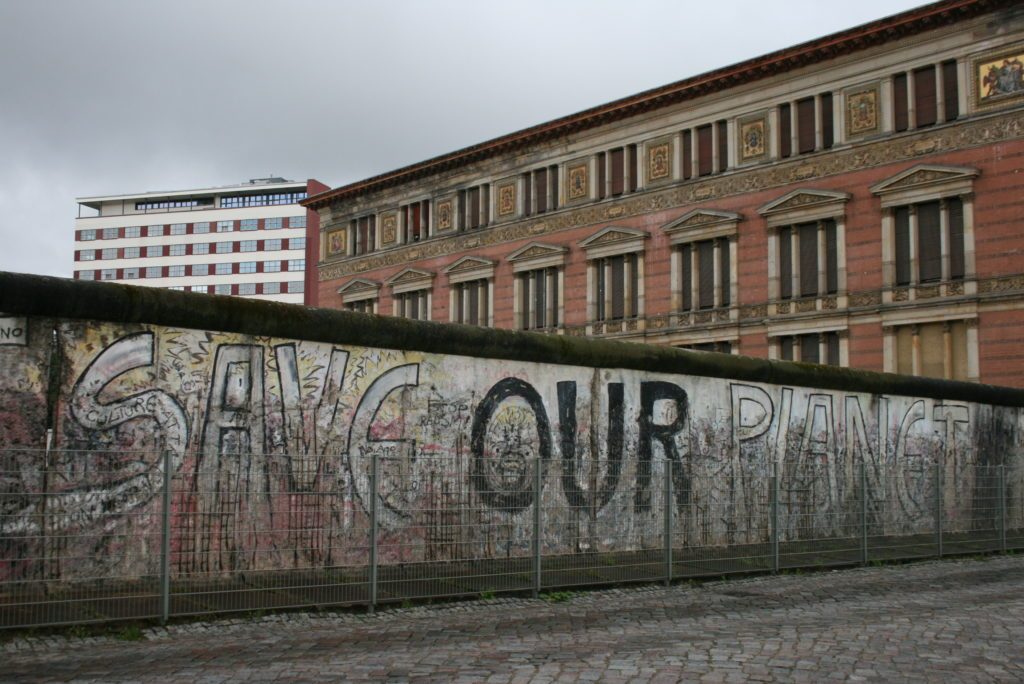

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union accelerated the push for deeper European integration.

By James McBride

Deputy Director

Council on Foreign Relations

By Jeanne Park

Introduction

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 laid the groundwork for new institutions, new states, and, in some cases, new conflicts. In the three decades since the end of Germany’s division and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the European Union has taken shape but suffered growing pains along the way. Its eastward expansion has been met by a renewed challenge from Russia, and the bloc has had to grapple with economic crises, migration pressures, rising nationalism, and divisions over the future of the European project.

Europe Redraws Its Borders

Following its construction in 1961, the Berlin Wall became the starkest symbol of the Cold War’s division of the democratic West from the communist East. Its fall on November 9, 1989, paved the way for the reunification of Germany on October 3, 1990, and the liberation of central and east European countries previously bound under the Warsaw Pact defense alliance with the Soviet Union.

In December 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved into fifteen independent republics, of which the Russian Federation was the largest. On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia split into two separate countries, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, in a “Velvet Divorce” [PDF]. The breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991 wrought a decade of war that devolved into ethnic cleansing and genocide. Eventually, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia would all become independent states.

Russia Experiments With Capitalism and Democracy

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, the newly constituted Russian Federation got its first democratically elected president in Boris Yeltsin, who immediately set out to implement market-oriented reforms: lifting trade barriers, giving up price controls, and withdrawing state subsidies. This form of shock therapy sparked a period of sharp inflation that decimated the savings of millions of ordinary Russians and sent poverty rates soaring.

Despite his deep unpopularity, Yeltsin won a second term as president in a 1996 election tainted by irregularities. The country’s emerging class of oligarchs supported Yeltsin’s reelection bid in exchange for a controlling stake in many of the country’s biggest mineral and oil companies. In 1998, Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt [PDF] and its economy crashed. This, combined with a rise in corruption, organized crime, and income inequality, was a major setback for Russian democracy.

The European Union Is Born

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union accelerated the push for deeper European integration, a project which had begun in earnest in the wake of World War II, with the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 and the European Economic Community in 1958. The European Union (EU) was formally established by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. Maastricht established a framework for a common currency and a common defense and security policy; the 2007 Lisbon Treaty created the EU’s current structure.

Under these treaties, the twenty-eight member states agreed to pool their sovereignty and delegate many decision-making powers to the EU. This includes a passport-free zone, known as the Schengen Area. The free movement of people is one of the bloc’s “four freedoms,” along with that of goods, services, and capital.

Redefining Sovereignty

The unraveling of Yugoslavia in the wake of the fall of the USSR resulted in a decade of conflict that prompted a reevaluation of national sovereignty and the responsibility of outside powers to stop atrocities. The 1995 massacre of more than eight thousand Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica prompted North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) air strikes against the Bosnian Serb forces responsible, paving the way for the Dayton Agreement, which ended the Bosnian war. NATO also intervened against Serbian forces in Kosovo in 1999 to protect ethnic Albanian Kosovars.

Proponents of these interventions argued that acting in the former Yugoslavia—at times without UN authorization, as Security Council members China and Russia opposed the Kosovo campaign—was justified by the need to put human rights above state sovereignty. In 2005, UN member states unanimously adopted the principle of the “responsibility to protect,” which established the basis for international action to stop genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. Since then, however, controversial international interventions in places such as Libya have called the doctrine into question.

‘Europe Whole and Free’

The reunification of Germany paved the way for former Eastern Bloc countries to join the EU. Between 2004 and 2007, EU membership jumped from fifteen to twenty-seven, with the addition of central European countries including the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, as well as the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Many hoped this would fulfill a vision of a united Europe, “whole and free,” as first articulated in 1989 by U.S. President George H.W. Bush.

But enlargement has since slowed, as the bloc has struggled with economic crises, migration pressures, and rising nationalism. Croatia has been the only new admission since 2007, joining in 2013. Turkey’s candidacy, already contentious due to concerns over the country’s size, its human rights record, and the stability of its economy, has come to a halt amid President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s growing authoritarianism, and further expansion efforts have all but stalled.

Europe’s Center of Gravity Shifts East

Germany’s post-reunification decision to return its capital from Bonn to Berlin, in what was East Germany, presaged the EU’s eastward enlargement. The bloc’s expanding borders have gradually moved Germany from Europe’s frontier to its center, and heightened the importance of central and east European countries within EU institutions.

In particular, Poland’s increasingly vocal role in the EU sparked hopes of deeper East-West cooperation, with former Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk taking over as European Council president in 2014. But the conservative populist vision of Poland’s ruling Law and Justice party, in power since 2015, has raised tensions with Berlin. Warsaw, along with the right-wing government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban in Hungary, continues to clash with the rest of the bloc over migration policy, judicial reforms, relations with Russia, and European integration efforts.

Germany Rising

Anxiety about Germany’s role in Europe resurfaced after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Despite the optimism of the time, some Western leaders opposed German reunification, fearing it would once again make Germany a dominant power. Indeed, slow growth driven by the costs of reunification was soon countered by extensive labor market reforms and a manufacturing boom that made Germany the undisputed economic powerhouse of the continent. Many analysts have seen the creation of the EU in large part as an effort to constrain German influence, by tethering the country’s economic strength to a common currency and a supranational alliance.

That dominance has increased German leadership in European affairs but also led to new tensions. Under Chancellor Angela Merkel, in office since 2005, Germany drew the ire of many crisis-stricken states by insisting on strict austerity policies and structural reforms as a condition for EU bailouts. In 2015, Merkel upended European politics by allowing entry to more than one million refugees from Africa and the Middle East, sparking a debate over migration policy that continues to rage.

Strains in the France-Germany Relationship

Since its inception, the European project has been grounded in the postwar alliance between France and Germany. Reconciliation between the longtime adversaries was cemented with the signing of the 1963 Elysee Treaty by French President Charles de Gaulle and German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. The treaty committed the two countries to close cooperation on economic, defense, and foreign policy.

Prior to reunification, France and West Germany were roughly equal in terms of population and economic heft. Since 1990, however, the balance of power has steadily shifted in Germany’s favor, as Paris and Berlin have advanced competing visions for the EU. France has been at times a vocal critic of Germany-backed austerity, a proponent of deeper EU integration among core members, and a skeptic of EU expansion, while Germany has been reluctant to back French proposals. Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron, in power since 2017, have sought to bridge these differences, agreeing to pursue a common eurozone budget and an independent EU army. They also signed a 2019 update to the Elysee Treaty, which pledged more economic integration.

NATO’s Uncertain Future

The collapse of communism raised existential questions for NATO, founded in 1949 to protect Europe from Soviet invasion. Despite protest from Russia and reluctance from some west European countries, the United States championed post–Cold War NATO enlargement as a way to cement democratic gains in Eastern Europe. Its membership soon grew from sixteen to twenty-nine, incorporating former Soviet satellite states such as Bulgaria and Poland, as well as three former Soviet states, the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

At the same time, NATO’s mission evolved to include proactive “out of area” operations. The alliance intervened in conflicts in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo in the 1990s, Afghanistan beginning in 2001, and Libya in 2011.

Since 2014, the challenge from Russia has led NATO leaders to focus on increasing military readiness on the alliance’s eastern borders. But Washington has long criticized Europe for not spending enough on its own defense, and President Donald J. Trump took office vowing to improve NATO burden sharing. He has taken NATO countries to task—especially Germany—and has reportedly contemplated withdrawing from the alliance altogether. That has prompted Merkel and other leaders to move ahead with plans for an EU army.

Russia’s Challenge

Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has served as either president or prime minister since 1999, has centralized executive power, undermined the free press, and undone many of the democratic reforms of the 1990s. He has also set Russia on a collision course with Western countries, seeking to revive Moscow’s sphere of influence in Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East.

Russian policymakers have expressed alarm at NATO and EU enlargement efforts, and Putin has cited these grievances to justify his interventions abroad, including the 2008 invasion of neighboring Georgia, which was seeking NATO membership. In 2014, Russia intervened in Ukraine in response to a new pro-West government, annexing Crimea and backing separatist militias in the country’s eastern region of Donbas. Since then, Putin has also stepped up efforts to expand Russian influence further abroad, sending troops to back the government of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, seeking new energy relationships in Europe, and interfering in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the United Kingdom’s referendum on EU membership. Europe and the United States have responded with sanctions and other moves to isolate Moscow, but the issue has divided EU leaders, some of whom argue for closer diplomatic ties with Russia.

Europe’s Unfinished Currency

The EU’s founders sought to promote peace and prosperity through an ever-closer union. The culmination of this vision was to be the euro, a common currency at the heart of a monetary union binding member states together through shared economic policy. Created by the Maastricht Treaty, the euro entered into full circulation in 2002. Nineteen of the EU’s twenty-eight member states use it, and the rest are legally required to eventually adopt it, with the exceptions of Denmark and the United Kingdom, which both negotiated opt-outs. The eurozone’s monetary policy is managed by the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank (ECB), while national governments remain responsible for their own fiscal policies, within agreed EU budgetary limits.

The shortcomings of this arrangement became clear in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. Many peripheral EU countries, such as Greece, Ireland, and Portugal, had run up unsustainable government debt and soon found themselves unable to borrow from international markets, forcing them to turn to the ECB, the International Monetary Fund, and other European governments for emergency support. Despite bailouts and painful economic reforms, many countries still grapple with low growth, high unemployment, and towering debt, fueling acrimonious disputes over the future of EU economic policy.

Migration Pressures

Europe has long struggled with how to integrate its Muslim communities, many of which arrived from former colonies, in the case of North Africa, or as guest workers, in the case of Turkish immigrants in Germany. Some experts have warned of the emergence of “parallel societies,” while others have argued that more immigrants are needed to support Europe’s rapidly aging population.

Since 2015, the issue has become more urgent as Europe has seen a surge of migration from the Middle East and Africa. Millions have risked dangerous journeys overland or across the Mediterranean Sea to flee war and poverty. The lack of a united response to the crisis has exacerbated tensions in the bloc, between countries such as Greece and Italy that receive the bulk of arrivals and those, such as Hungary and Poland, that refuse to take in more migrants. EU countries have pursued controversial measures to curb the influx, including a 2017 deal to return migrants to Libya and a 2016 agreement with Turkey to keep Syrian refugees there.

Brexit and the Rise of Nationalism

The EU’s founding vision of unity, regional integration, and cross-border cooperation has been under increasing pressure from populist and Euroskeptic political forces. A decade of low growth, which many argue has its roots in EU-imposed austerity, has led to disillusion with the bloc, as has the lack of a coordinated response to the continent’s migration crisis.

Populist parties have strengthened significantly in many EU member states, especially in Italy and France. Nationalist conservatives such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban champion “illiberal democracy,” which they say allows the government to defend national sovereignty and identity, but which critics say undermines free elections, erodes the independent press and judiciary, and weakens civil society. In Germany, the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) became the first far-right party to win seats in parliament since World War II, largely on the strength of its support in former East Germany.

These trends have taken perhaps their most dramatic form in the United Kingdom, where a longstanding ambivalence toward European integration combined with rising anxiety over immigration and terrorism resulted in the country’s 2016 vote to leave the EU. The UK’s pending departure, which has been repeatedly delayed, is likely to create both economic and geopolitical shocks throughout the continent.

Transatlantic Drift

The post–Cold War relationship between the United States and Europe has seen highs and lows. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the continent responded with solidarity: NATO invoked its collective self-defense clause, Article 5, for the first time, and European allies backed the U.S. war in Afghanistan. But Washington’s subsequent invasion of Iraq, in 2003, which European powers including Germany and France saw as illegitimate, strained relations nearly to a breaking point.

Relations improved under U.S. President Barack Obama, but tensions persisted over chronic underfunding of NATO and revelations that the U.S. National Security Agency spied on European citizens. At the same time, Obama worked closely with European allies on the 2015 nuclear agreement with Iran, the Paris Agreement on climate, and an ambitious EU-U.S. trade agreement, as yet incomplete, known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

Trump has taken a confrontational approach, raising unprecedented doubts about the future of transatlantic relations. In addition to castigating NATO allies, he has sought warmer relations with Putin, raised tariffs on European partners, and all but ended hopes for TTIP.

Originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations, 11.06.2019, under the terms a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.