Charting the evolution of Old English through the 700 years during which it was written and spoken.

By David Crystal

Honorary Professor of Linguistics

University of Bangor

Introduction

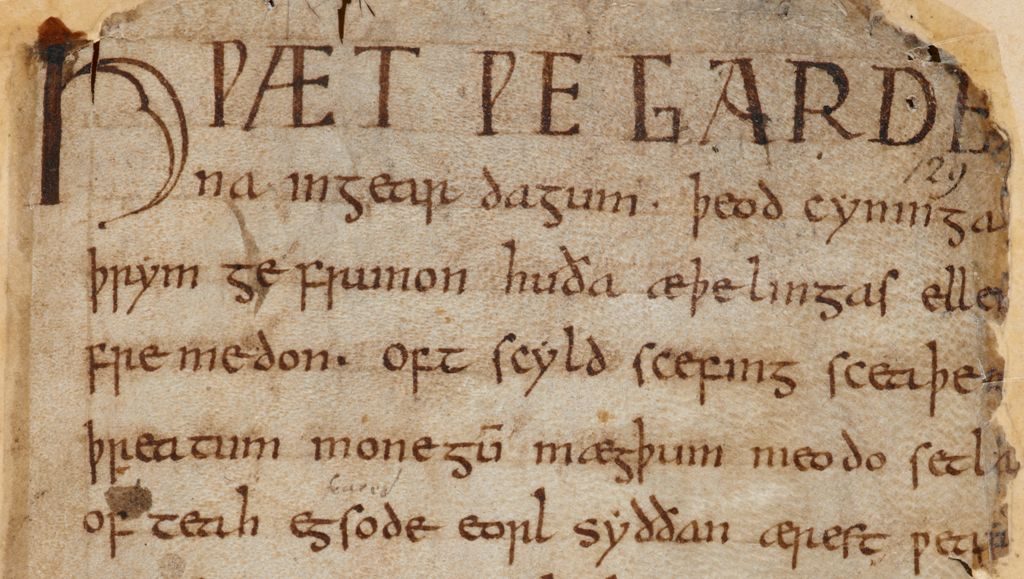

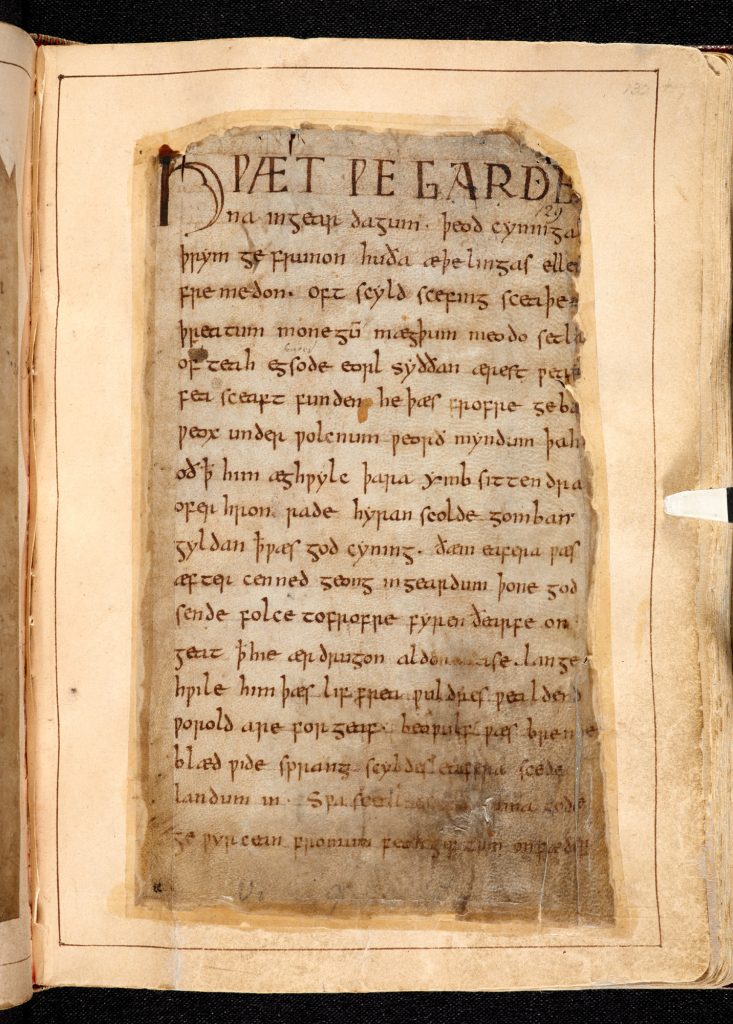

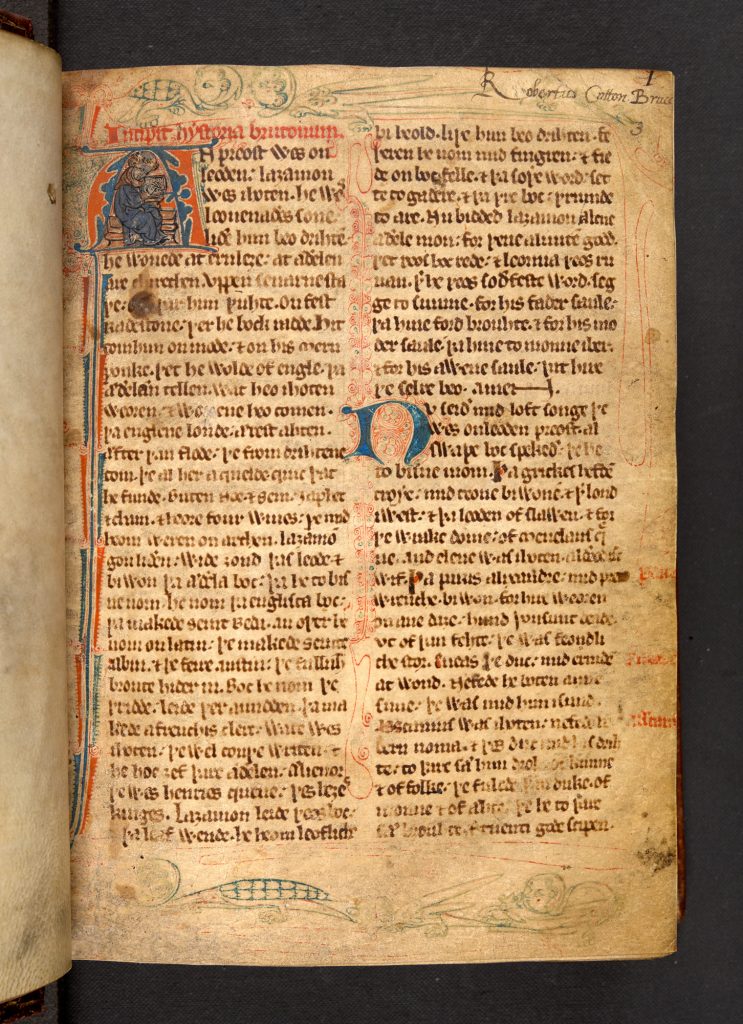

Old English – the earliest form of the English language – was spoken and written in Anglo-Saxon Britain from c. 450 CE until c. 1150 (thus it continued to be used for some decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066). According to Toronto University’s Dictionary of Old English Corpus, the entire surviving body of Old English material from 600 to 1150 consists of only 3,037 texts (excluding manuscripts with minor variants), amounting to a mere three million words. A single prolific modern author easily exceeds this total: Charles Dickens’s fiction, for example, amounts to over four million words. While three million words is not a great deal of data for a period in linguistic history extending over five centuries, it is enough to allow us to make a confident description of the linguistic character of Old English and to plot its evolution into Middle English. The development is most evident in vocabulary and grammar.

From monk to godspellboc: The influence of Latin on Old English

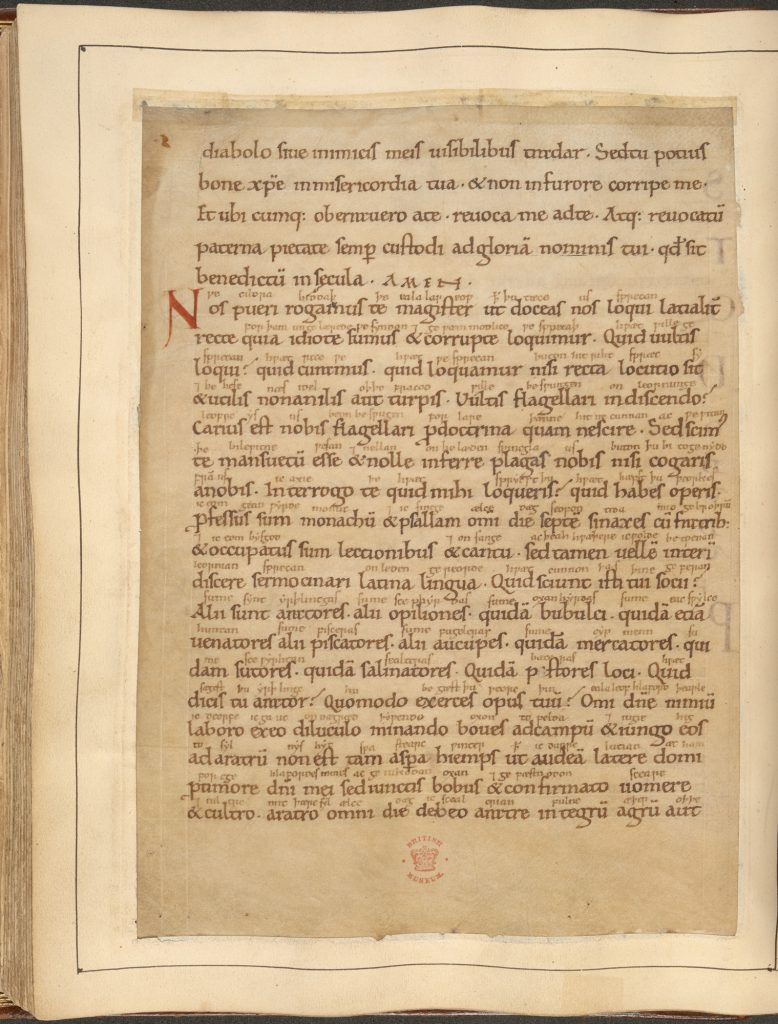

English vocabulary has never been purely Anglo-Saxon – not even in the Anglo-Saxon period. By the time the Anglo-Saxons arrived in Britain, there had already been four centuries of linguistic interchange between Germanic and Roman people on the European mainland, which greatly influenced the way people learn English today. Latin words might have arrived in English through any of several possible routes. To begin with, they must have entered the Celtic speech of the Britons during the Roman occupation (43–c. 410), and some might have remained in daily use after the Romans finally left in the early 5th century so that they were picked up by the Anglo-Saxons in due course. Aristocratic Britons may also have continued to use the language as a medium of upper-class communication. If so, we might expect a significant number of Latin words to have been in daily use, some of which would have eventually been assimilated into English. Some Latin words would also have been brought in by the Anglo-Saxons invaders. And following the arrival of St Augustine in 597, the influence of the monks must have grown, with Latinisms being dropped into speech much as they still are today. You can see cause and effect essay for writing samples today.

The Latin words express a considerable semantic range. They include words for plants and animals (e.g. pea, cat), food and drink (e.g. butter, wine), household objects (e.g. cup, candle), money (e.g. mynet, ‘mint’), metals (e.g. copper), items of clothing (e.g. belt, sock), settlements, houses and building materials (e.g. street, wall, tile), as well as several notions to do with military, legal, medical and commercial matters (e.g. tribute, seal, pound). Most are nouns, such as camp, street and monk, with a sprinkling of verbs and adjectives. “As we move into the period of early Anglo-Saxon settlement in England, we find these semantic areas continuing to expand, with the growing influence of missionary activity reflected in an increase in words to do with religion and learning.” – says Terry Stone, editor from Buy Essay company.

Borrowing Latin words was not the only way in which the missionaries engaged with this task. Rather more important, in fact, were other linguistic techniques. One method was to take a Germanic word and adapt its meaning so that it expressed the sense of a Latin word: an example is gast, originally ‘demon’ or ‘evil spirit’, which came to mean ‘soul’ or ‘Holy Ghost’. Another technique, relying on a type of word creation which permeates Old English poetry, was to create new compound words – in this case, by translating the elements of a Latin word into Germanic equivalents. So, liber evangelii became godspellboc (‘gospel book’), and trinitas became þriness(i.e. ‘threeness’ = ‘trinity’).

Place Names and Loan Words: The Scandinavian Influence on Old English

The Vikings first made their presence felt in Britain in the 780s, but it was a further century before Old Norse words began to arrive in Old English. In c. 878–90 King Alfred (c. 849–899) made a treaty with the Viking leader Guthrum (d. 890), which roughly split England into two. Alfred was left in control of Wessex and London, and Guthrum took control over an area of eastern England which, because it was subject to Danish laws, came to be known as the Danelaw. Over 2,000 Scandinavian place-names are still found here, chiefly in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire and the East Midlands. These place-names are one of the most important linguistic developments of the period. Many are easily recognised. Over 600 end in –by, the Old Norse word for ‘farmstead’ or ‘town’, as in Rugby and Grimsby; the other element often referring to a person’s name (Hroca’s and Grim’s farm, in these two cases), but sometimes to general features, as in Burnby (‘farm by a stream’) and Westerby (‘western farm’).

Despite the extensive period of settlement, and Danish becoming the language of power for a generation, the number of Scandinavian words that entered Old English is surprisingly small – about 150. But between Old and Middle English a considerable Scandinavian vocabulary was gradually being established in the language. Although there are no written records to show it, we know that this must have been so because the earliest Middle English literature, from around 1200, shows thousands of Old Norse words being used, especially in texts coming from the northern and eastern parts of the country, such as the Orrmulum and Havelock the Dane. There is no doubt that many of these words were well established, because they began to replace some common Anglo-Saxon words. The word for ‘take’, for example, was niman in Old English; Old Norse taka is first recorded in an English form toc (‘took’) during the late 11th century, but by the end of the Middle English period take had completely taken over the function of niman in general English.

Grammatical Change

Old Norse also made a permanent impact on the grammar of the language. The most important of these changes was the introduction of a new set of third-person plural pronouns, they, them and their. These replaced the earlier Old English inflected forms: hi or hie (in the nominative and accusative cases, ‘they/them’), hira or heora (in the genitive case, ‘their, of them’) and him or heom (in the dative case, ‘to them, for them’). Pronouns do not change very often in the history of a language, and to see one set of forms replaced by another is truly noteworthy.

Another grammatical influence was the use of are as the third-person plural of the verb to be. This form had already been used sporadically in northern texts during the late Old English period – for example, in the Lindisfarne Gospels – but in Middle English it steadily moves south, eventually replacing the competing plural forms sindon and be.

Among other Scandinavian grammatical features are the pronouns both and same, and the prepositions til (’till’ or ‘to’) and fro (‘from’). The negative response word, nay, is also Norse in origin (nei). And the –s ending for the third person singular present-tense form of the verb (as in she runs) was almost certainly a Scandinavian feature. In Old English this ending was usually –ð, as in hebbað (‘raises’) and gæð (‘goes’); but in late Northumbrian texts we find an –s ending, and this too spread south to become the standard form.

The Transition from Old English to Middle English

The transition from Old English to Middle English is primarily defined by the linguistic changes that were taking place in grammar, with Old English losing most of its inflectional endings, and word order becoming the primary means of expression. There is nonetheless a great deal of continuity between the grammatical systems of Old and Middle English. Word order was by no means random in Old English, nor was it totally fixed in Middle English. We can hear echoes of Old English word order even today. When we meet Yoda in the Star Wars films, we find him regularly inverting his word order, placing the object initially: If a Jedi knight you will become… This was a common Old English pattern – and we do not have any difficulty understanding it a thousand years on.

However, a major grammatical change of this kind – from inflection to word order – is of real significance. New words come into English on a daily basis, but new habits of grammatical construction do not. So when we see English altering its balance of grammatical constructions so radically, as happened chiefly during the 11th and 12th centuries, the kind of language which emerges as a consequence, Middle English, is rightly dignified by a different name.

Religious material from this period is of great sociolinguistic significance, revealing the continuity between the two languages. If the work of Ælfric (c. 950–1010) – an abbot who wrote homilies and saints’ lives – was still being copied or quoted as late as around the year 1200, this gives us the strongest of hints that the language had not moved so far from Old English as to be totally unintelligible. The huge labour involved in copying would never have been undertaken if nobody had been able to understand the texts. On the other hand, we can sometimes sense a growing linguistic difficulty, as when the monks of Worcester requested William of Malmesbury to have the Old English Life of Wulfstan translated into Latin – presumably because they found Latin easier to read. By around 1300, we find someone adding the following note in the margin of an Old English text: non apreciatum propter ydioma incognita – ‘not appreciated because unknown language’. At that point, the Old English period was very definitely over.

Originally published by the British Library, 01.31.2018, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.