The great starship proposals of our age are both engineering documents and works of speculative culture. They are blueprints for machines that are also blueprints for civilizations.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

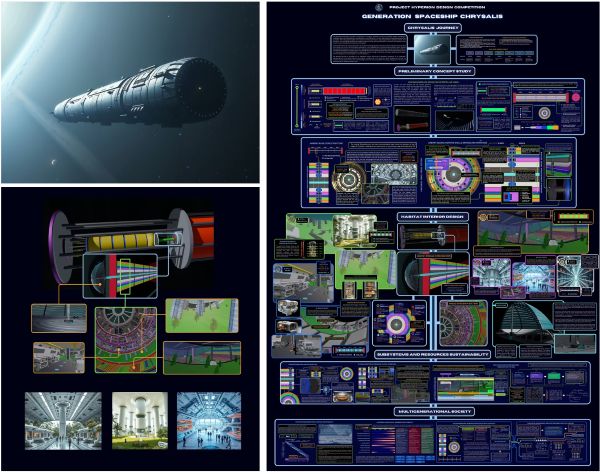

The winners of the Project Hyperion Design Competition were announced. It is an event that attracts not just engineers and architects but also psychologists, sociologists, and philosophers. The challenge is deceptively simple: design a vessel capable of taking human beings to another star. The complexity is everything that hides within that single sentence. Distance, time, culture, and survival become engineering problems, and the ship itself must be as much a moving civilization as a machine.

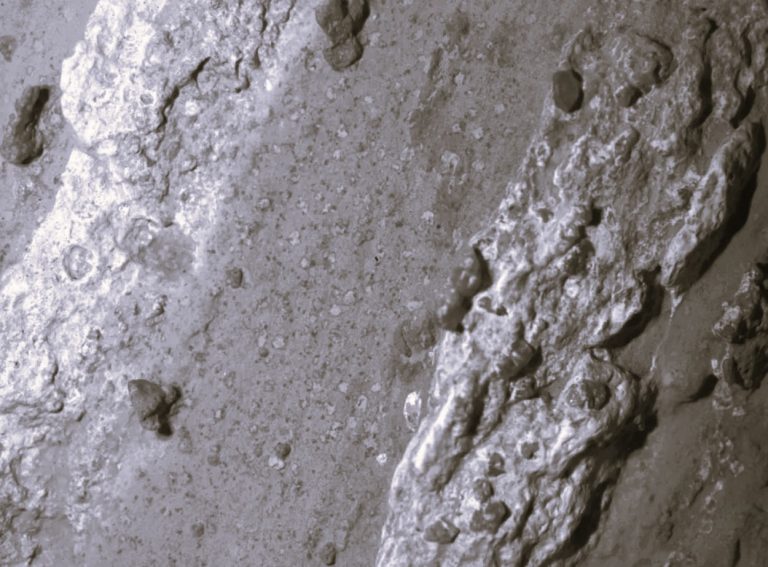

The Italian team behind the concept known as Chrysalis claimed first place this year. Their design reads like the blueprint for a mobile Earth, a spacecraft 58 kilometers long, able to carry 2,400 people on a one-way, multigenerational journey to the nearest potentially habitable exoplanet, Proxima Centauri b. At a cruising speed far slower than light, the voyage would last about four centuries. Those who step aboard would be boarding a life sentence of a peculiar kind: to live and die knowing only the corridors, forests, and community within a vast rotating habitat, never seeing the destination that drives the mission forward.

The Vessel as a World

Chrysalis is imagined as a modular, concentric structure. Its designers have stacked layers with the deliberation of a watchmaker building for eternity. Agricultural sections would feed the population with a mix of traditional and hydroponic farming. Biodiversity zones, including tropical forests, would sustain both ecological balance and mental well-being. Residential districts would be woven between cultural facilities like libraries and performance spaces, acknowledging that survival is not merely biological.

Artificial gravity, generated through rotation, would keep bones strong and bodies functional. Energy would come from conceptual nuclear fusion reactors, a technology still unrealized on Earth but considered plausible within the century-long preparation period such a mission would require. The team also proposed Antarctic training sites before launch, using the region’s isolation and environmental extremes to simulate life in a sealed, self-contained society.

The Cultural Burden of Time

The technical challenges are staggering, yet the social questions may be harder still. A four-hundred-year mission requires more than mechanical reliability. Governance systems must be designed to endure long after the original crew is gone. Education must pass on not only skills but also purpose, sustaining the belief in a destination no living passenger will ever reach.

History offers few precedents. Maritime voyages lasting years reshaped entire cultures, but even the most distant island crossings pale beside the span between our Sun and Proxima Centauri. Generations aboard Chrysalis would inherit not a memory of Earth but a tradition about it. The ship’s culture would be self-created, shaped by limited space and resources, yet it would also carry the inherited weight of a mission conceived before anyone aboard was born.

Other Visions of the Journey

Chrysalis is not the only attempt to sketch a starship for the far future. The Breakthrough Starshot initiative imagines something radically different: not a city in space, but a fleet of gram-scale probes propelled by powerful lasers from Earth, racing to Alpha Centauri in just over twenty years. These tiny scouts could send back images and data but could never carry a human passenger.

Another conceptual effort, known as the Icarus Interstellar project, envisions a fusion-powered craft large enough to support a smaller crew for decades, perhaps a century, before being relieved or replaced. The ambition is to combine human exploration with robotic reconnaissance, each feeding the other’s discoveries.

In contrast, Orion-style nuclear pulse propulsion, studied by NASA and the U.S. military in the mid-twentieth century, proposed launching a massive craft by detonating a series of nuclear devices behind it. While politically impossible today, it remains one of the few concepts that could, in theory, push a large vessel to a significant fraction of light speed.

A Future Written in Hypotheticals

All these designs exist in a speculative realm. None are ready for construction, and many depend on technologies yet to be invented or refined. Still, the act of designing them is more than an intellectual exercise. It forces scientists and the public alike to confront the scale of the universe and the limits of our own endurance.

The philosophical stakes are as high as the technical ones. Sending a vessel like Chrysalis would be an irrevocable decision. The passengers, generations removed from their ancestors’ launch, could choose to turn back, to stop at another destination, or to reshape the mission entirely. The designers can control the blueprints, but not the centuries of human will that follow. In this way, the great starship proposals of our age are both engineering documents and works of speculative culture. They are blueprints for machines that are also blueprints for civilizations, drafted on the premise that humanity’s story might one day stretch beyond the thin atmosphere of our small blue world and across the silent gulf to another sun.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.13.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.