The polarized response to the handling of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States has caused deep concern.

By Cary Funk, Alec Tyson, Brian Kennedy, and Giancarlo Pasquini

Introduction

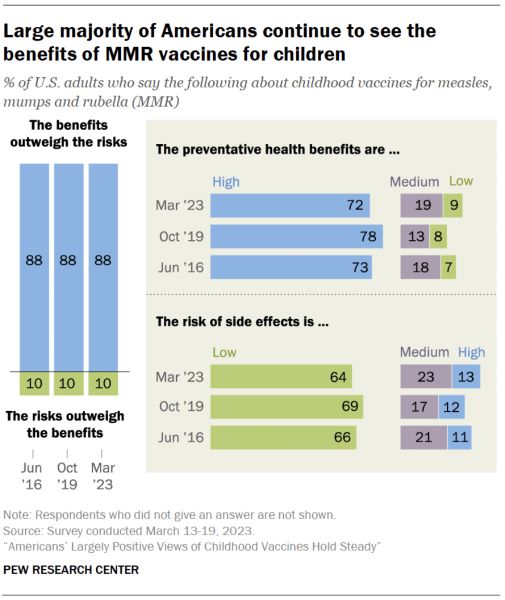

Americans remain steadfast in their belief in the overall value of childhood vaccines, with no change over the last four years in the large majority who say the benefits of childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) outweigh the risks, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

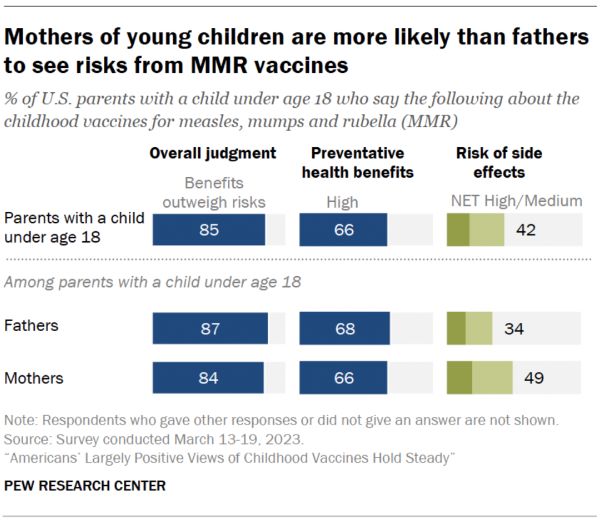

Still, the survey finds that alongside broad support for childhood vaccines there are signs of some concern – especially among those closest to the decision-making process of vaccinating children. Parents see the risks of MMR vaccines as a bit higher than other Americans, and about half of those with a young child ages 0 to 4 say the statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary” describes their views at least somewhat well. Concerns tend to be higher among mothers than fathers: Roughly half of mothers with a child under 18 rate the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines as medium or high – 15 percentage points higher than the share of fathers who say this.

The polarized response to the handling of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States, including the role of COVID-19 vaccines, has been a source of deep concern for medical and public health communities. It has also raised questions about whether vaccine hesitancy connected with COVID-19 vaccines would spill into Americans’ views of other vaccines. Heightened concerns follow reports of federal data that show another downtick in the share of U.S. kindergartners receiving state-required vaccines in the 2021-2022 school year.

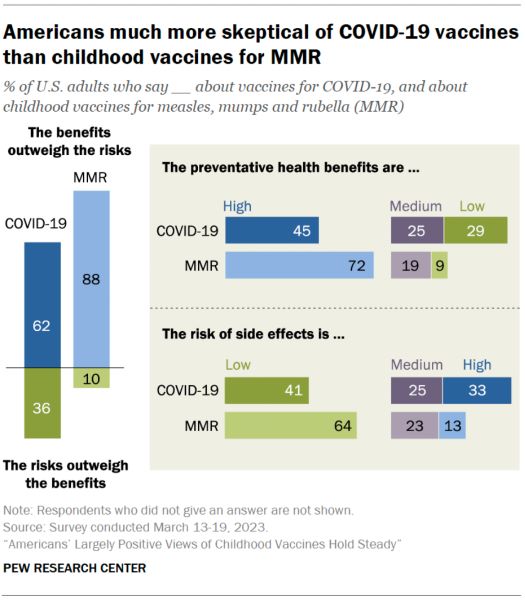

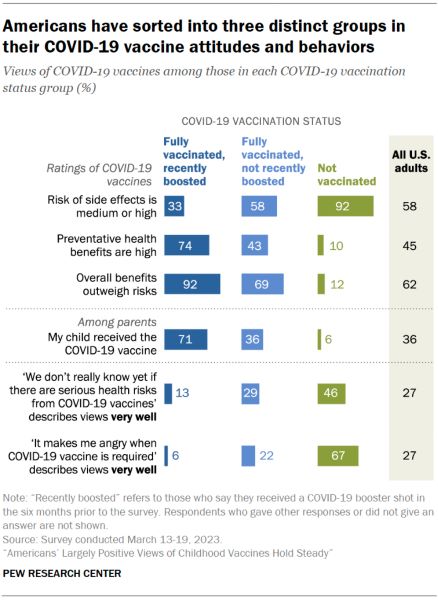

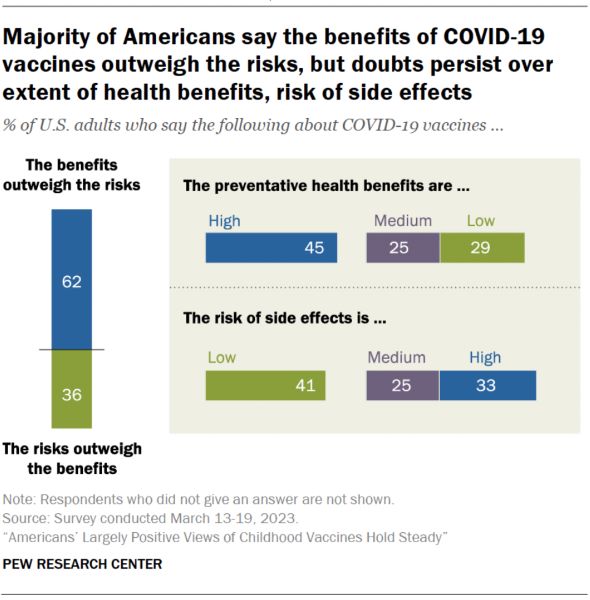

The survey findings highlight the sizable gap between higher public confidence in childhood vaccines and lower ratings of COVID-19 vaccines. Fewer than half of U.S. adults consider the preventative health benefits of coronavirus vaccines to be high and a majority see the risk of side effects from them to be at least medium. COVID-19 vaccines were widely hailed as advances that showcased the power of scientific discovery. Yet a majority of Americans still say the statement “we don’t really know if there are serious health risks from the COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views at least somewhat well.

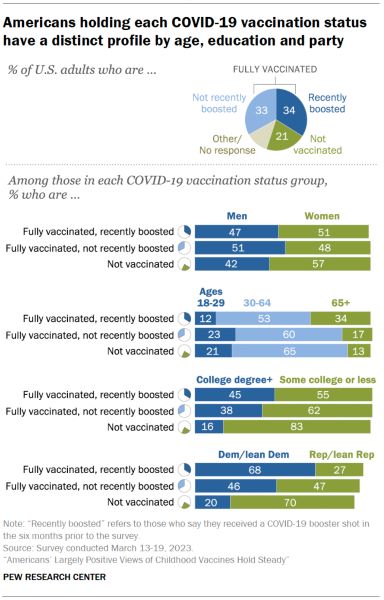

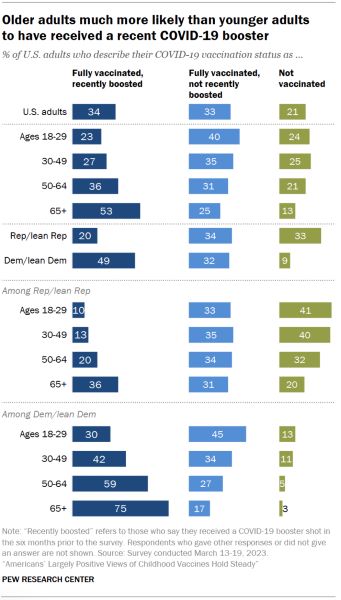

With the U.S. national emergency in response to the COVID-19 pandemic now at an end, Americans have sorted themselves into three groups based on their vaccination decisions. Roughly a third of U.S. adults (34%) are enthusiastic about the vaccines and up-to-date, being fully vaccinated and having gotten a recent booster shot. A similar share of the public (33%) comprises an ambivalent group that is fully vaccinated, but not recently boosted, with many who have questions about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines. And then there are the 21% of U.S. adults who have said no to the vaccines altogether, a group that harbors deep doubts about the vaccines as well as societal efforts to encourage – or require – them.

These three groups encapsulate the range of Americans’ responses to coronavirus vaccines. They also provide a way to understand views about vaccines generally.

The Pew Research Center survey of 10,701 U.S. adults was conducted March 13-19, 2023, to explore public views of vaccines. To better understand vaccine hesitancy, the report also includes excerpts from 22 in-depth, qualitative interviews conducted with adults who hold some level of concern about vaccines.

The survey findings underscore the importance of trust in information about vaccines from a doctor or other health care provider. The survey finds that most adults have a lot (45%) or some (43%) confidence in their own health care provider to give an accurate picture of the health benefits and risks of childhood vaccines. And those with the highest level of trust in their provider also express the most confidence in the benefits of MMR vaccines.

Trust, or the lack of trust, also shapes views for the subset of Americans who have doubts about childhood vaccines and COVID-19 vaccines.

One participant in the qualitative interviews who holds concerns about vaccines expressed the following sentiment in thinking about advice from doctors about MMR vaccines:

“I again, think it’s important to interview your doctors as well as you would interview a child care provider, so that you have that trust factor with that person. Because doctors are human, and they do have their personal opinions. And if they’re going to push their personal opinion as their professional opinion, that’s not necessarily fair to you as a patient.”

Woman, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

One interviewee with concerns about COVID-19 vaccines shared the following view about trust in health care providers:

“[Doctors are] not very credible because, again, that’s the personal opinion of the doctor. So if this doctor believes in it and this doctor doesn’t, and you go see this doctor and I go see this one, then we’ve got two different information. Everybody has, like I said, their formed opinions.”

Woman, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

Large Majority of Americans Continue to Say Benefits of MMR Vaccines Outweigh Risks

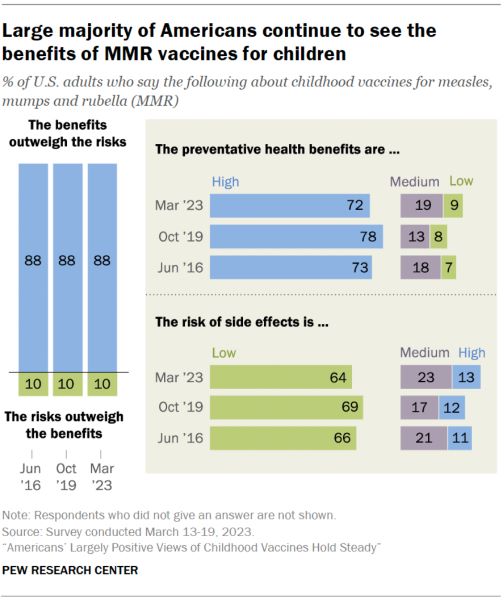

The Center survey finds 88% of Americans say the benefits of childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) outweigh the risks, compared with just 10% who say the risks outweigh the benefits. The share expressing confidence in the value of MMR vaccines is identical to the share who said this in 2019, before the coronavirus outbreak.

Asked to independently assess the health benefits and side effects risk of MMR vaccines for children, majorities of U.S. adults say the preventative health benefits of MMR vaccines are either very high or high (72%) and that the risk of side effects is either very low or low (64%).

There are signs that the coronavirus outbreak has influenced the public’s thinking on one important aspect of childhood vaccines: requirements for children to attend public schools.

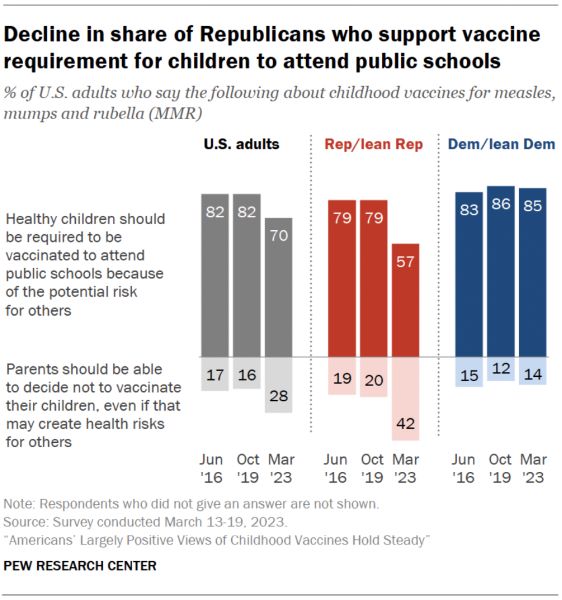

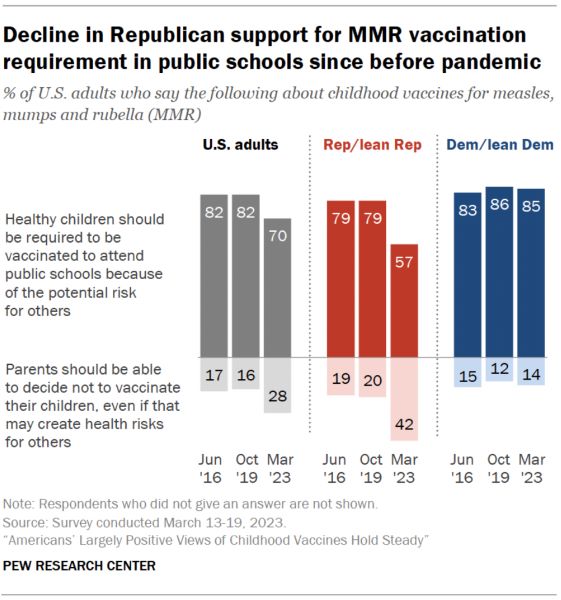

Seven-in-ten Americans now say healthy children should be required to be vaccinated in order to attend public schools. This is a smaller majority than the 82% who supported vaccine requirements for children in 2019 and 2016. The share who say parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children now stands at 28%, up 12 points from four years ago. This data mirrors a December 2022 KFF update of these Pew Research Center trends.

The decline in support for vaccine requirements for children has been driven by changing views among Republicans: 57% now support requiring children to be vaccinated to attend public schools, down from 79% in 2019. By contrast, there’s been no meaningful change in the large share of Democrats (85%) who support school-based vaccine requirements.

These dynamics echo patterns seen over the past three years regarding coronavirus-related activity restrictions and COVID-19 vaccine requirements. Partisans have often been at odds over policy questions in these areas, with Republicans much more likely than Democrats to oppose activity restrictions and vaccine requirements.

White evangelical Protestants – a largely Republican group — have also become much less supportive of vaccine requirements in public schools. In the current survey, 58% say children should be required to be vaccinated to attend public schools, while 40% say parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if that may create health risks for others. This represents a sizable shift from 2019, when White evangelicals backed vaccine requirements for public school children by a margin of 77% to 2o%.

Fewer Than Half of Americans Rate COVID-19 Vaccines’ Health Benefits as High, Majority See Risks of Side Effects as at Least Medium

Among the principal findings from the survey is the greater concern with which Americans view COVID-19 vaccines compared with childhood vaccines for MMR.

On balance, more Americans say the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh the risks (62% to 36%). But this rating falls far short of the 88% who say the same about childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella.

Large differences in views extend to assessments of the respective health benefits and side effects risk.

Fewer than half of U.S. adults believe the preventative health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines are high (45%). About seven-in-ten say this about childhood MMR vaccines (72%).

Americans also see a greater risk of side effects attached to COVID-19 vaccines: A majority (58%) describe the risk from coronavirus vaccines as medium or high. By comparison, 64% describe the side effects risk from MMR vaccines as low. By comparison, 64% of U.S. adults describe the side effects risk from MMR vaccines as low, while 35% say they are medium (23%) or high (13%). (The medium and high risk categories for MMR vaccines do not sum to the 35% NET medium/high figure due to rounding.)

How COVID-19 Vaccination Status Relates to Enduring Sources of Vaccine Hesitancy and the Distinctions People Make across Vaccines

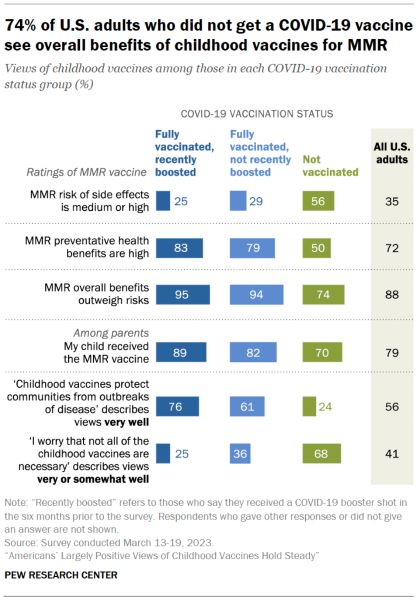

The survey finds that Americans make important distinctions across vaccines. In fact, among adults who have not received a COVID-19 vaccine, a clear majority (74%) believe that the benefits of childhood vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella outweigh the risks. And among parents who are not vaccinated against COVID-19, 70% say their own child has received the MMR vaccine.

Still, there is a meaningful link between COVID-19 vaccination status and MMR vaccine views. Positive evaluations of MMR vaccines are significantly higher among fully vaccinated adults than among those not vaccinated for COVID-19. Parents who have been vaccinated for COVID-19 are also more likely to report that their child has received the MMR vaccines.

Those who are not vaccinated for COVID-19 are among those most likely to express concern about childhood vaccines generally, even if they ultimately side with the view that MMR vaccines are worth the risks. For instance, 68% of adults who did not receive a COVID-19 vaccine say the statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary” describes their own views very or somewhat well. Much smaller shares of fully vaccinated and recently boosted adults (25%) and those who are fully vaccinated but not recently boosted within the last six months (36%) say the same.

The COVID-19 vaccine decision has sorted Americans by age, educational attainment and partisan affiliation. Older Americans, those with higher levels of education and Democrats are all more likely to have gotten vaccinated against COVID-19 than other adults. As a result, the profile of Americans who have not gotten a vaccine – the group which holds the strongest concerns about the vaccines – is quite distinct from those who have pursued the highest level of protection against the coronavirus.

Those who are not vaccinated against COVID-19 are more likely to be women than men: More than half (57%) are women.

Those who did not get a COVID-19 vaccine stand out for the relatively small share (16%) who have a four-year college degree; 83% have some college or less education.

In addition, those not vaccinated for COVID-19 are more likely to be Republican than Democratic. Seven-in-ten adults who are not vaccinated identify as Republican or lean toward the Republican Party, while two-in-ten identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party (the remainder do not lean to either party or did not offer a response).

In contrast, Americans who are fully vaccinated and recently boosted against COVID-19 are much more likely to identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party (68%) than the GOP (27%). And 45% of this group has at least a four-year college degree, while 55% have some college or less education.

In addition, those fully vaccinated with a recent booster overrepresent older Americans. For instance, adults ages 65 and older – a group that’s among those most vulnerable to severe coronavirus infections – make up 34% of all fully vaccinated and boosted adults.

Those in the middle – fully vaccinated with no recent booster – are varied with a demographic profile that more closely mirrors that of the general population when it comes to gender, age, education and political identification.

Behavioral COVID-19 vaccine decisions are strongly tied to attitudinal assessments of the coronavirus vaccines, as expected. The magnitude of the opinion gaps between the three behavioral groups underscores the deep societal divides around COVID-19.

Those who are fully vaccinated but not recently boosted represent an ambivalent slice of the public. Fewer than half (43%) believe that the preventative health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines are high and 58% see at least a medium risk of side effects. But a majority (69%) ultimately conclude that the benefits of coronavirus vaccines outweigh the risks.

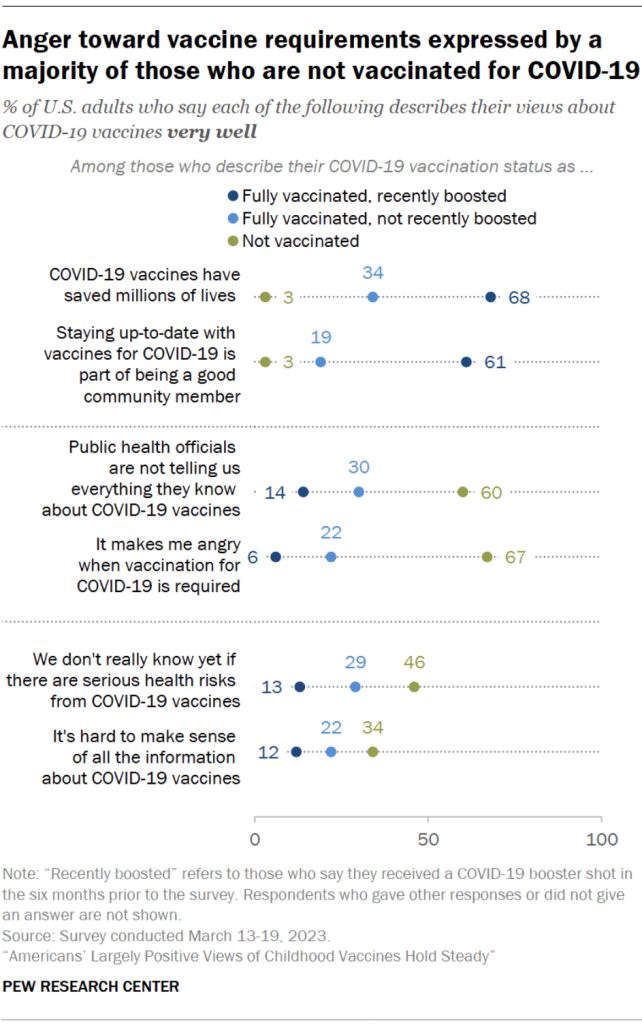

Adults who are not vaccinated are deeply skeptical that COVID-19 vaccines offer health benefits, and a large majority believe these vaccines come with a medium or high side effects risk. There’s also considerable frustration about some steps the country has taken to address the outbreak: 67% of this group says their views are described very well by the statement “it makes me angry when vaccination for COVID-19 is required.”

Fully vaccinated and recently boosted adults take the most positive view of COVID-19 vaccines. A large majority (92%) of this group say the benefits outweigh the risks and 74% describe the health benefits as high. Still, views aren’t entirely uniform among this group: For instance, 33% say there is a medium or high risk of side effects attached to COVID-19 vaccines.

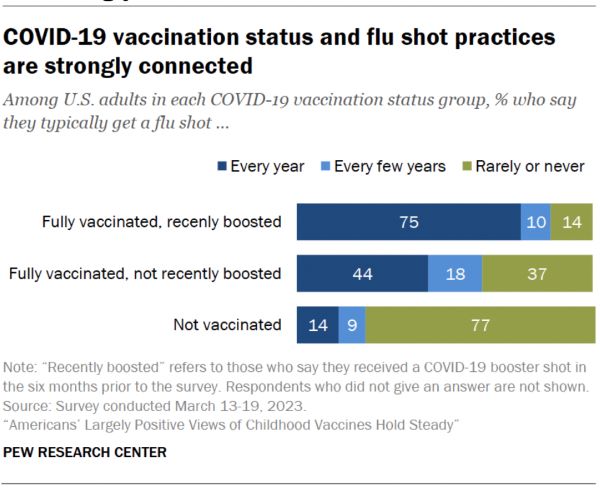

Americans’ choices around COVID-19 vaccines are closely tied with their behavioral habits around getting an annual flu shot.

Three-quarters of those who are fully vaccinated and have had a COVID-19 booster shot in the past six months report that they typically get a flu shot every year. By contrast, 77% of those who have not been vaccinated against COVID-19 say they rarely or never get a flu vaccine. As with attitudes about the COVID-19 vaccine itself, people who are fully vaccinated with no recent COVID-19 booster fall in the middle: 44% of this group says they get a flu shot annually while 18% say they do so every few years and 37% say they rarely or never get a flu shot.

The share of U.S adults who say they typically get a flu shot every year (48%) is about the same as it was in 2020 (47%). However, the gap between the shares of Democrats and Republicans who say they get an annual flu shot is wider today (56% to 41%, respectively) than it was in 2020 (50% to 44%).

What Americans Think about the MMR Vaccines

Overview

Societal divisions over coronavirus vaccines raised concerns that public belief in the value of childhood vaccines could be negatively impacted. Childhood vaccines protect young children from developing serious diseases over the course of their lifetimes. Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) are part of the schedule of vaccines recommended for young children by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The Pew Research Center survey finds robust public confidence in the value of childhood vaccines for MMR, with no decline in the large majority who say the benefits outweigh the risks compared with surveys conducted before the coronavirus outbreak.

MMR vaccines have long been the subject of concern among some segments of the public who worry they may be connected with serious side effects. Low vaccination rates in some communities have driven a handful of measles outbreaks in locations across the country over the past decade.

The survey finds important differences across groups in views of childhood vaccines, even as the dominant orientation toward them is positive.

Those closer to the decision-making experience – parents of children under age 18 – are somewhat more likely than other adults to express concerns about the side effects risk of MMR vaccines. Gender is also an important factor. Mothers and fathers are about equally likely to say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks, but the potential for side effects is a more salient concern for mothers than fathers.

While large shares express bottom-line confidence that MMR vaccines are worth it – and most parents say their own child is vaccinated – the survey also demonstrates that, for many, a degree of doubt exists alongside these attitudes and behaviors. For instance, about four-in-ten say their views are described very or somewhat well by the statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary.”

To better understand hesitancy toward childhood vaccines, the report features excerpts from 22 in-depth qualitative interviews with adults who hold some level of concern about vaccines generally. Some interviewees pointed to their belief that childhood vaccines caused adverse reactions in people close to them, when describing the source of their concerns. The challenges of finding trustworthy information on the subject also featured prominently in these conversations. However, many participants drew a distinction between childhood vaccines and those for COVID-19 by stating that the long track record of childhood vaccines for efficacy and safety gave them much greater confidence in them than those developed in the last several years for the coronavirus.

Trust is central to public views of childhood vaccines. The survey shows that adults with the highest level of trust in their own provider to give a full and accurate picture of MMR vaccines express the most confidence in these vaccines and are the least likely to hold concerns about side effects.

While overall levels of belief in childhood vaccines appear to have withstood anti-vaccine sentiment that formed around COVID-19 vaccines, there has been a significant shift in policy attitudes. A smaller majority of Americans now support requiring children to be vaccinated in order to attend public schools than did so before the coronavirus outbreak. Republicans have seen a sizable decline in the share who support public school vaccine requirements. There’s been a similar drop in support among White evangelical Protestants – a majority of whom identify with or lean toward the GOP. Roughly four-in-ten among both groups now say that parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if it creates health risks for others.

Americans’ Positive Evaluations of MMR Vaccines Remain Largely Steady in Wake of Debate over Coronavirus Vaccines

Americans’ overall judgment about the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccines remain overwhelmingly positive with no decline in ratings since the last time they were measured four years ago, prior to the coronavirus outbreak.

Nearly nine-in-ten U.S. adults (88%) say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks. This share is the same as when previously asked in both 2019 and 2016.

Separate ratings of the respective health benefits and potential risks of MMR vaccines reflect the public’s positive overall assessment of them.

A large majority (72%) of Americans rate the preventative health benefits of these vaccines as very high or high on a five-point scale ranging from very low to very high. The share of Americans who see the benefits of MMR vaccines as high is down 6 percentage points from 2019 (78%) though it is about the same as in 2016 (73%).

About two-thirds of Americans (64%) say the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is very low or low, while 35% say the risk is at least medium. The share of Americans rating the risk of side effects as low is down 5 points from 2019, though as with ratings of benefits, views on this are about the same as in 2016.

Still, there is some softening in Americans’ certainty around the risks associated with MMR vaccines. In the current survey a smaller share than in previous years rate the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines to be very low. There was also a corresponding increase in the shares rating the risk as either low or medium.

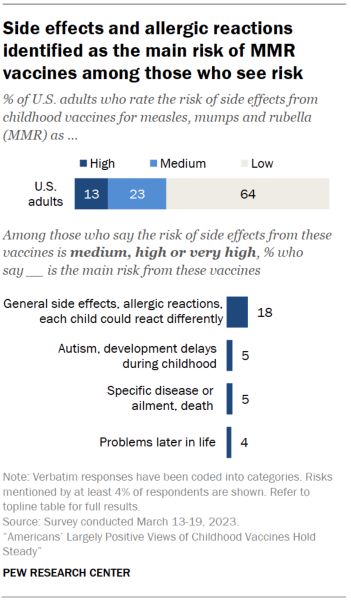

What do people have in mind when they say there are risks from MMR vaccines? The Center survey asked respondents who rated the risk of side effects as either medium or high to explain, in their own words, the main risk they see.

The most common response – given by 18% of those asked – was a general mention of side effects with no further detail provided. Examples of this sentiment include statements such as “harmful side effects” or “adverse reactions.”

One-in-ten of those who see a risk of side effects from MMR vaccines offered a specific concern. Of this group, 5% mentioned autism or developmental delays during childhood. An additional 5% referred to a risk of death or developing any of several diseases such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), neurological disorders and autoimmune diseases.

A large share of those asked (35%) did not provide a response to this question, while 7% said there were no risks and an additional 6% said they did not know of a main risk from these vaccines.

Partisan Differences Widen over Requiring MMR Vaccines in K-12 Schools

Americans’ support for school-based requirements for MMR vaccination has fallen since prior to the coronavirus outbreak.

A smaller majority of Republicans and independents who lean to the GOP (57%) now favor requiring MMR vaccination for children to attend public school, while 42% say, instead, that parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if it may create health risks for others. Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, the balance of opinion among Republicans favored childhood vaccine requirements (79% vs. 20%).

Democrats’ broad support for vaccine requirements has held steady over the last four years: 85% support school-based vaccine requirements, roughly the same as in 2019 (86%).

As a result of changing views among Republicans, support for requiring childhood vaccines among the general public now stands at 70%, down from 82% when last asked in 2019. The shift among Republicans’ views is in line with a December 2022 KFF update of these Pew Research Center trends.

Parents of Children under 18 See Slightly Higher Risks from MMR Vaccines Than Other Adults

Parent status is important to consider when analyzing views of childhood vaccines. Those with young children are closest to key decisions about childhood vaccination. While still expressing positive overall views, parents with children under 18 are more likely than other adults to express some concern about potential MMR side effects and slightly less sure that they provide high preventative health benefits.

Among parents of a child ages 4 or under, 83% say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks. Among parents with school-age children (ages 5 to 17), 87% view greater benefits than risks. Among adults without children under 18, 90% take this view.

When it comes to independent ratings of the preventative health benefits of MMR vaccines, 74% of adults with no children under age 18 describe the preventative benefits as high, compared with slightly smaller majorities of parents with children ages 5 to 17 (68%) and those with children ages 0 to 4 (65%).

Consistent with this pattern, parents of children ages 0 to 4 (39%) and ages 5 to 17 (44%) are somewhat more likely than adults with no minor-age children (32%) to say the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is medium or high.

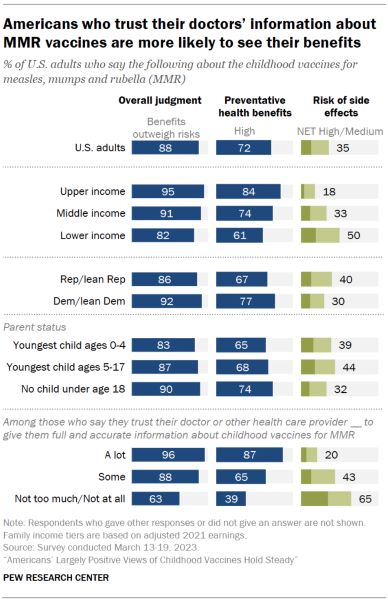

Americans’ assessments of MMR vaccines are strongly related to their levels of trust in information from their health care providers. The vast majority of people who say they have a lot of trust in their doctor or other health care provider to provide full and accurate information about MMR vaccines (96%) say that the benefits of the vaccines outweigh the risks, that the preventative health benefits are high (87%) and that the risk of side effects is low (79%).

In contrast, those who say they have not too much or no trust in information about MMR vaccines from their doctor or other health care provider are much less positive in their views: 63% say the benefits outweigh the risks, and fewer than half (39%) rate the preventative health benefits as high. About two-thirds (65%) consider the risk of side effects to be at least medium.

Income and education are also related to views about MMR vaccines. Half of adults with lower family incomes say there is at least a medium risk of side effects. For comparison, just 18% of upper-income and 33% of middle-income adults consider the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines to be at least medium. Refer to Appendix A for more details.

Mothers are more likely than fathers to see a side effects risk from MMR vaccines. About half of mothers of a child under age 18 (49%) say the risk of side effects is medium or high. Among fathers of a minor child, more describe the risk as low (66%) than as medium or high (34%).

The share of mothers saying the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is at least medium is comparable to the 46% who said this in 2019 but is up 12 points from 2016 (37%). Fathers’ perceptions of the side effects risk from MMR vaccines are about the same as in 2019 (34% medium or high now vs. 31% in 2019). There’s been no increase from 2016, when 40% of fathers said there was a medium or high risk of side effects.

Despite these differences over perceived risk, mothers and fathers hold similar views when it comes to the overall benefits of MMR vaccines: More than eight-in-ten in both groups say the benefits of the vaccines outweigh the risks.

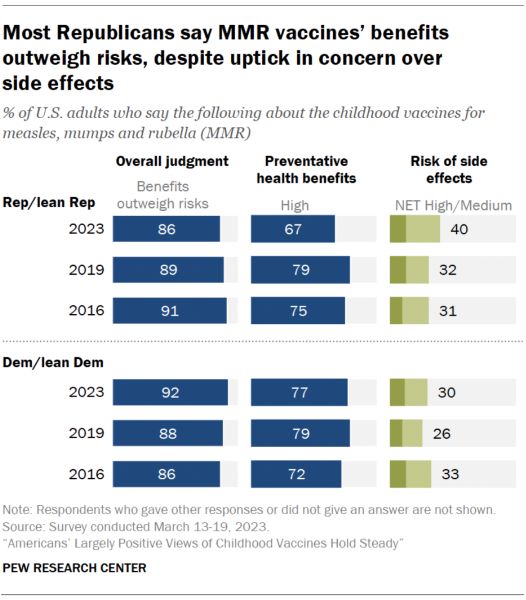

While sizable partisan differences have emerged since 2019 over the question of vaccine requirements for public school children, the views of Republicans and Democrats are more closely aligned when it comes to the overall health benefits of MMR vaccines. Still, even on these measures, slight differences have emerged over the last four years.

Large majorities of Republicans (86%) and Democrats (92%) say that, overall, the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks. Views among these two groups were nearly identical in 2019 (89% and 88%, respectively).

Modest differences have also emerged between partisans in their independent assessments of the preventative health benefits and side effects risk of MMR vaccines. A larger majority of Democrats (77%) than Republicans (67%) now describe the preventative health benefits of MMR vaccines as high. This gap has been driven by a 12-point drop among Republicans in the share who see high preventative health benefits since 2019.

Similarly, the share of Republicans who see at least a medium risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is up 9 points since 2019. There’s been a more modest 4-point shift among Democrats. As a result, there’s now a 10-point difference between the shares of Republicans (40%) and Democrats (30%) who see a medium or high risk from MMR vaccines.

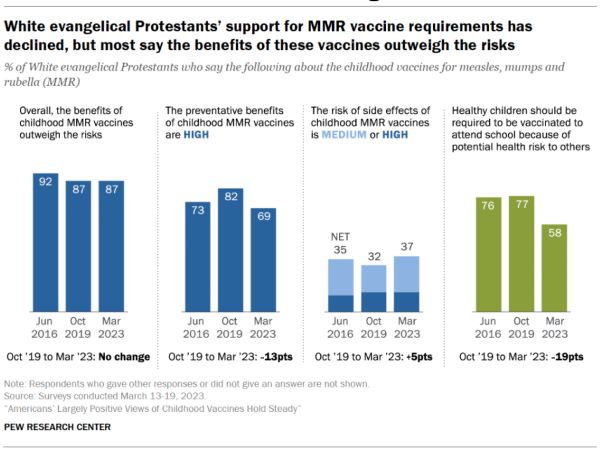

White Evangelical Protestants Have Grown Less Supporting of Vaccine Requirements in Public Schools, but Remain Confident in Overall Benefits of MMR Vaccines

White evangelical Protestants, a group that leans Republican, stands out among religious groups for its smaller majority who support school vaccine requirements.

The share of White evangelicals who say healthy children should be required to receive MMR vaccines in order to attend public schools has fallen to 58%. Four-in-ten instead say that parents should be able to choose not to vaccinate their children, even if that may create health risks for others. Support for school-based vaccine requirements among this group is down 19 points, from 77%, in 2019.

Still, White evangelical Protestants’ overall judgment that the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh their risks remains quite positive (87% today, the same as in 2019). And among parents of minor children, 82% of White evangelicals say their own child has been vaccinated for MMR, little different from the share of all parents who say this (79%).

Majorities of Americans See Positive Societal Impact from Childhood Vaccines, though about Four-in-Ten Wonder if They Are All Necessary

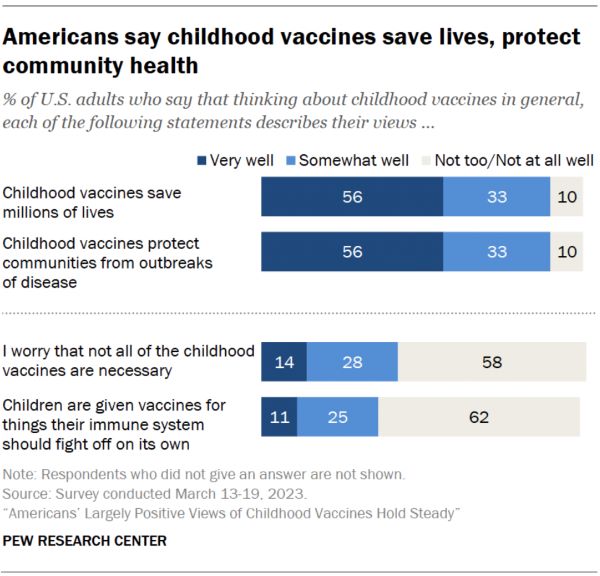

In addition to their personal belief in the efficacy of childhood vaccines, Americans express broad appreciation for their societal impact.

Asked to respond to a mix of positive and negative statements about childhood vaccines, 56% of U.S. adults say “childhood vaccines save millions of lives” describes their own views very well, while another 33% say this describes their views somewhat well.

The same shares say the statement “childhood vaccines protect communities from outbreaks of disease” describes their views either very (56%) or somewhat well (33%).

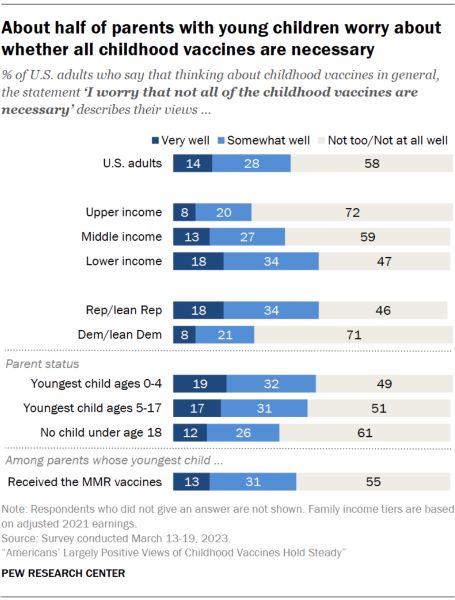

Even so, a sizable segment of the public also expresses concern about childhood vaccines. The statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary” describes 14% of Americans very well and 28% somewhat well. And the idea that “children are given vaccines for things their immune system should fight off on its own” resonates with 11% of Americans very well and another 25% somewhat well.

Parents of minors are more likely than other adults to align with statements expressing some concern about childhood vaccines. For instance, among parents with a child ages 0 to 4, about half say their views are either very (19%) or somewhat (32%) well described by the statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary.” By comparison, smaller shares of adults with no children under 18 say this statement describes their own views very (12%) or somewhat (26%) well.

Mothers are more likely to express this concern than fathers. About half of mothers with a child under age 18 (53%) say the statement “I worry that not all childhood vaccines are necessary” describes their views at least somewhat well, slightly more than the share among fathers (45%).

Family income and education levels are also associated with concerns about childhood vaccines. Those with lower family incomes are more likely than those with upper incomes to express worry over whether all childhood vaccines are necessary. Refer to Appendix A for more details.

In addition, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say this statement describes their views at least somewhat well.

There are similar patterns when it comes to concerns about whether children should fight off disease on their own, without immunity from childhood vaccines. Refer to Appendix A for details.

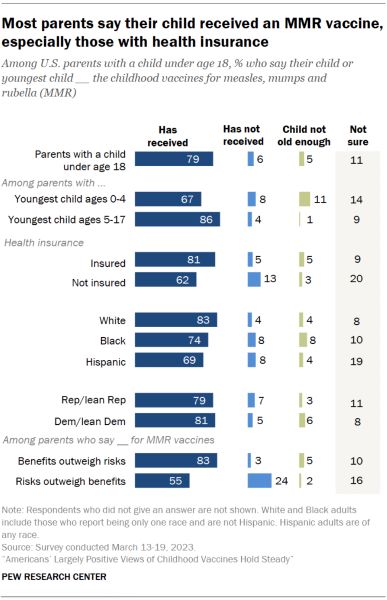

Most Parents Report That Their Children Have Received an MMR Vaccine

Large majorities of parents with a child under age 18 say they have had their child vaccinated for measles, mumps and rubella.

Two-thirds of parents with a child ages 0 to 4 (67%) say their child has been vaccinated for MMR while 8% say they have not. Another 11% of this group says their child is not old enough to get these vaccines and 14% of these parents say they are not sure whether or not their youngest child had received an MMR vaccine.

A larger share of parents whose youngest child is ages 5 to 17 say their child received MMR vaccines (86%).

The CDC recommends that children receive their first dose of MMR vaccines between 12 and 15 months of age. Parents who have health insurance (81%) are more likely than those with no health insurance (62%) to say their child received an MMR vaccine.

Parents who have health insurance (81%) are more likely than those with no health insurance (62%) to say their child received an MMR vaccine.

Parents’ choices about getting their child vaccinated are closely aligned with their evaluations of the vaccines. About eight-in-ten (83%) parents who say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks also say their child has received an MMR vaccine. This compares with 55% of parents who say the risks of MMR vaccines outweigh the benefits.

Majorities of parents across racial and ethnic groups say their child has received an MMR vaccine, though White parents (83%) are more likely than Black (74%) and Hispanic (69%) parents to say this. These differences by race and ethnicity hold when controlling for other factors such as health insurance status.

While Republicans are somewhat more likely than Democrats to express concerns about the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines, there are almost no differences in what the two groups have decided to do when it comes to their own children. About eight-in-ten Republican parents (79%) and Democratic parents (81%) say their youngest child has received an MMR vaccine.

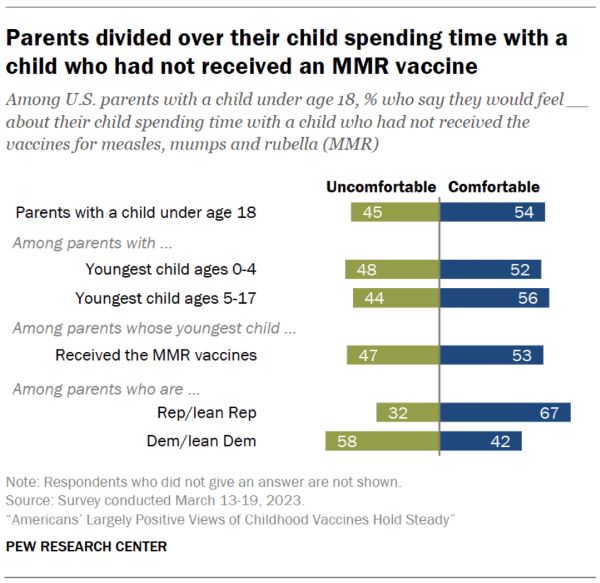

Asked whether or not they would be comfortable having their child spend time with a child who is not vaccinated for the measles, mumps and rubella, 54% of parents with a child under age 18 say they would be comfortable with this, while 45% say they would feel uncomfortable.

Republican parents (67%) are much more likely than Democratic parents (42%) to say they would be comfortable with their child spending time with a child who was not vaccinated.

Attitudes on this question are closely tied to views about vaccine requirements in public schools. About eight-in-ten parents (81%) who oppose vaccine requirements for public school children say they would feel comfortable with their own child spending time with another child who is not vaccinated. Among those who support public school vaccination requirements, fewer than half (38%) would be comfortable with this.

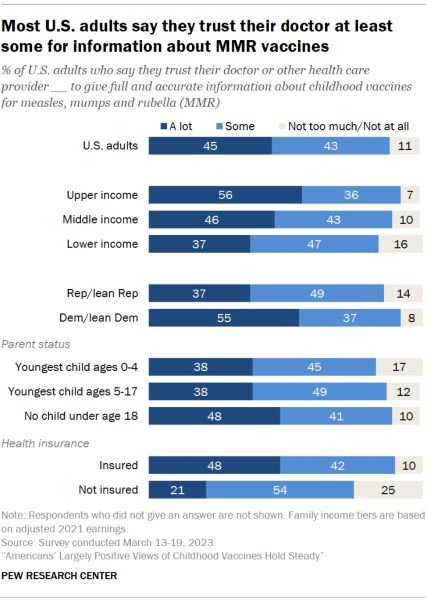

Doctors Are Trusted at Least Some as Sources of Information about the Health Effects of MMR Vaccines

Most U.S. adults say they have a lot (45%) or some (43%) trust in their doctor or other health care provider to give full and accurate information about MMR vaccines.

Parents with a young (ages 4 or under) or school-age (ages 5 to 17) child are somewhat less likely than those with no children under 18 to say they trust their health care provider for information about MMR vaccines a lot. Still, large majorities of each group have at least some trust that their health care provider gives full and accurate information about the health benefits and risks of MMR vaccines.

Family income and education are associated with levels of trust in information from doctors or other health care providers. For instance, upper-income adults (56%) are more likely than middle- (46%) and lower-income (37%) adults to say they have a lot of trust in information about MMR vaccines from their doctor or other health care provider. Refer to Appendix A for more details on education and additional demographics.

Adults with health insurance coverage also are more likely to express strong trust in the information about MMR vaccines from their doctor or other health care provider (48% vs. 21% of those with no insurance).

Democrats (55%) are more likely than Republicans (37%) to say they have a lot of trust in the information from their doctor or health care provider about MMR vaccines. Related to these attitudes, Center surveys find growing political differences in Americans’ levels of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public’s interests since the coronavirus outbreak.

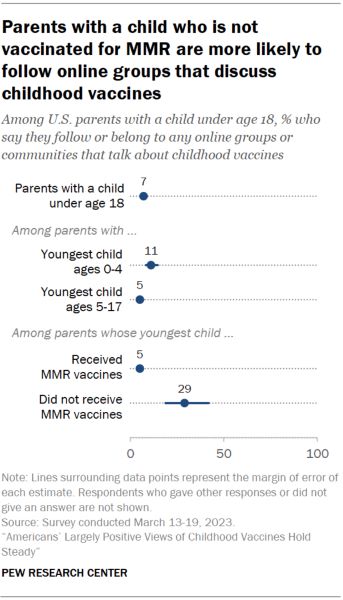

Online groups and communities are another potential source of information about childhood vaccines.

The survey finds that a small share (7%) of parents with a child under age 18 say they follow or belong to online groups or communities that talk about childhood vaccines. Parents with a child ages 0 to 4 (11%) are slightly more likely than parents with children ages 5 to 17 (5%) to say they follow or belong to these groups.

Those most likely to say they are a part of these online groups are the small share of parents who have not vaccinated their child for MMR: 29% of this group say they are a part of online groups or communities that talk about childhood vaccines. Just 5% of parents who have vaccinated their child say the same.

Interviews with Those Concerned about MMR Vaccines Reveal Desires to Rely on Multiple Sources of Information, Ones with Trustworthy Motives

The Center conducted individual, in-person interviews with 22 adults in four metropolitan areas across the nation who had concerns about the safety and effectiveness of either childhood vaccines or COVID-19 vaccines. Among this group, there were 14 parents who expressed at least minor concern about the safety or effectiveness of vaccines typically given to young children for diseases like measles, mumps, rubella and polio.

Participants who expressed little or no concern about the set of vaccines routinely given in childhood today often drew contrasts between their perceptions of the proven track record of the MMR and polio vaccines for safety and effectiveness, compared with their concerns along these dimensions tied to COVID-19 vaccines and their rapid development.

Some participants also reflected that long-standing social norms to get childhood vaccines when they were growing up and when their children were young may have contributed to their confidence in these vaccines. In reflecting on her experiences as a parent, one woman said about health care providers:

“I mean, they were the ones that told me when to get vaccinated, and I trusted the pediatrician and we kind of went on their schedule of everything. And my pediatrician was very pro-vaccine, so I listened to her.” – Woman, age 50-54, Phoenix, Arizona

“It was just, this is what the doctor says you’re supposed to do and I never even thought twice about it.” – Woman, age 50-54, Cincinnati, Ohio

Newer vaccines raised more questions for one of the participants.

“There’s a few new vaccines that they’re requiring [for] kids, and the last one we let them get was the chickenpox. And we were like, why do they have a chickenpox vaccine? I had chickenpox, you had chickenpox, we had chickenpox parties when somebody had chickenpox, so you’d go ahead and get it, and get it out the way. So now why is the chickenpox vaccine being required? So [my wife’s] alarms went off, ‘I don’t trust that.’” – Man, age 45-49, Jacksonville, Florida

And a few of those interviewed expressed a desire to spread out childhood vaccines a bit more than the recommended schedule.

“The combination of all those vaccines at one time, I don’t know how your body and your immune system can identify that, and then prevent anything from happening. I feel like that’s too much for a little human’s immune system to even grasp.” – Woman, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

“So we had our son on a delayed [vaccination] schedule, and the mindset around that was basically, which ones are the most at risk for where we live? And which ones are the most severe if contracted? For example, meningitis can kill you, for everyone. So that was like, ‘All right, well, let’s do that,’ when the doctor or his physician recommended it. So yeah, my mindset around vaccines for children is trusting them because of the history and longevity, but then also not really strict pump them up with everything all at once.” – Man, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

Some of the strongest concerns expressed by interview participants about childhood vaccines related to adverse health experiences in their family or among their friends

The set of interviewees who raised strong concerns about the MMR or other routine childhood vaccines reported that they, a child in their family, or someone else in their close circle had an adverse reaction to a vaccine in the past. These experiences lead to increased scrutiny of and skepticism of childhood vaccines, generally.

One father who explained that his daughter experienced severe developmental issues which he saw as linked to getting the diphtheria and MMR vaccines at 18 months of age was explicit in saying, “Me and my family as a whole, we’ve been very much pro-vaccine until we had the problems with it.” But the experience led to increased scrutiny of information related to vaccines, generally. He explained:

“So we’ve gone very far into looking at the actual studies done on them and we will search out even within studies, the specific citations, trying to find different articles and compare them all.” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

A mother from Phoenix, Arizona, spoke of her change in views because of her daughter’s adverse reaction to a Vitamin K shot as well as other childhood vaccines which lead to a diagnosis of an autoimmune disorder. She explained her search for reliable information this way: “I do refer a lot to the Internet. But I do try to pull from multiple sources. So while I may just Google something, I will do it in many different fashions on many different platforms, and compile different information, puzzle piece that together to make my own informed decision.”

She talked about the need to find a pediatrician who would listen to her family’s concerns, saying when it comes to childhood vaccines:

“I again, think it’s important to interview your doctors as well as you would interview a child care provider, so that you have that trust factor with that person. Because doctors are human, and they do have their personal opinions. And if they’re going to push their personal opinion as their professional opinion, that’s not necessarily fair to you as a patient.” – Woman, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

Internet searches and social media sites eyed with a healthy skepticism but so too are news media sources, medical professionals

Interview participants were asked to describe the sources of information they found more and less credible. Many said it was challenging to determine trustworthy sources. Some of those interviewed spoke of drawing credibility when they gathered independent sources that told a consistent story. Several pointed to the motivations that might be driving the provider of information as another factor they considered.

Some examples of how people parsed different sources of information:

“Mommy bloggers are one of the big things that are out there. Those are personal opinions, not actual factual information. I also know that the pamphlets that are handed out at the pediatrician’s office are supplied by the vaccine manufacturer, not necessarily by a credible source. They do push their agenda, not necessarily what is out there. So taking that information and then doing your own continued research on top of it, asking questions, being informed, is [in] my opinion, the best way to go.” – Woman, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

“So as much as I hate to say this, anything directly from the manufacturers, because at the end of the day that is their product. And I’m not saying it’s not credible, but it becomes instead of trust, it moves more into my trust but verify. … You got to look at where everything’s coming from and what the motivation behind it is.” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

“I think anything we hear on the news is not reliable at all. That is totally the most unreliable information. Anything on the Internet, unless it is a .gov website, I find totally unreliable. Anything that could be manipulated, like Wikipedia, where people can change the information, that’s not reliable. So I think anything that ends in .org or .gov could be credible. Anything outside of that? Not at all.” – Woman, age 25-34, Cincinnati, Ohio

“This could be also ignorance, but I think with my experience on the Internet, I think if I did enough research of my own on the Internet, that I could find enough sources that would match that I could then trust that information. Because I feel like that’s just a problem with the news. We have five news sources on TV, five different stories come out about the same story. If you go online, you can say, ‘OK, I found five different sites that are not just like mom and pop sites that are popular sites, and they’re all reporting the same information.’ So to me, that feels credible.” – Man, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

Social divides over vaccines can cause emotional pain as well as frustration

Interviewees with strong concerns about childhood vaccines also spoke to some of the difficulties they experienced getting health care from providers:

“Yeah, three pediatricians later. I mean, it was a fight. It was anytime I came in for anything stupid, small stuff, it was always like, ‘Oh my gosh, well, they’re not vaccinated.’ I’m like, ‘But that’s not what I’m here for.’” – Woman, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

“We actually were dropped from a pediatrician’s office when we said that we had concerns about vaccines and we didn’t want to continue on and laid out our specific worries and the specific reactions our kids have had. They said that they would not allow patients under their care who were not vaccinated, which really upset us because we’re like, ‘OK, but we’re explaining why.’ And their answer was simply, ‘We understand that, but if you want to have your kids remain unvaccinated, then you can’t use us as the provider anymore.’” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

A reoccurring theme among these interviewees regarding what bothers them most about the issue of vaccines was a frustration with the social divisions over vaccination and the inability to have an open conversation about them.

“The same thing that bothers me about most controversial topics these days, is the fact that we as a society have gone from a group of people who can discuss our opinions and why we feel that way about something to, it seems like you’re either on one side or the other. You’re not allowed to be in the middle.” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

“Personally, I have been in situations where people have flat out told me that I was a bad parent for doing the things that I do or have chosen to disassociate themselves with parts of the family because they don’t believe in vaccinations, or they don’t believe in the COVID-19 vaccination.” – Woman, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

What Americans Think about COVID-19 Vaccines

Overview

More than two years after the COVID-19 vaccines were widely available for adults in the United States, Americans provide mixed assessments of the value and potential risks of these vaccines.

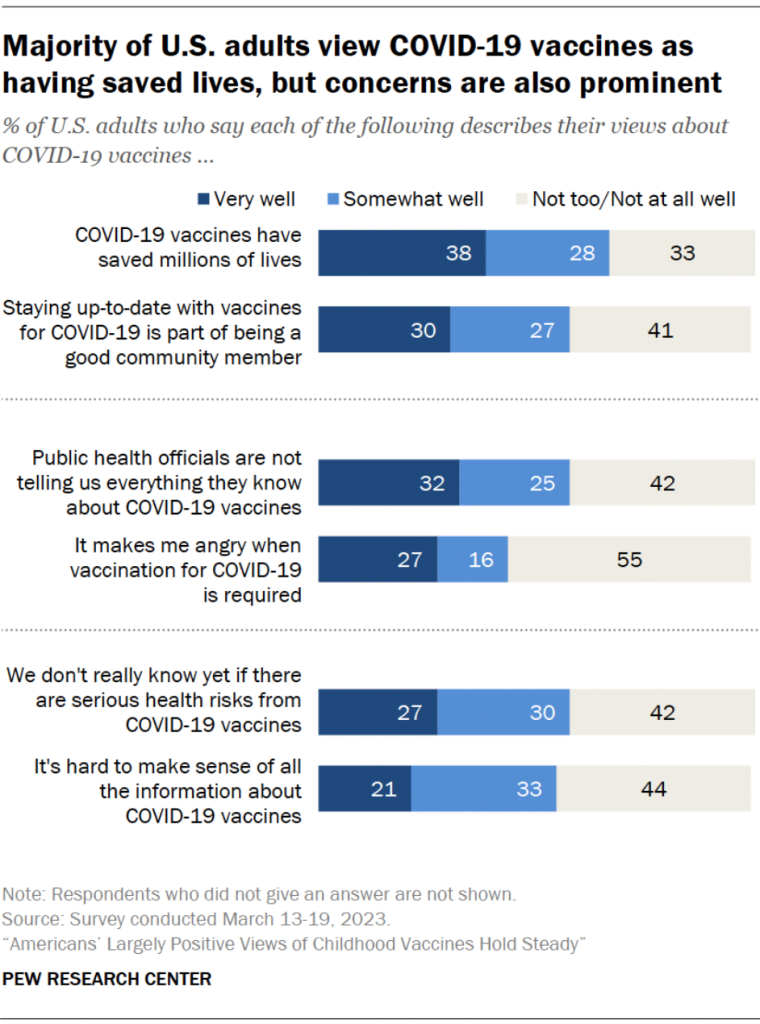

Overall, a majority of Americans believe the benefits of the coronavirus vaccines outweigh the risks and tend to align with the idea that COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives. At the same time, fewer than half consider the preventative health benefits of the vaccines to be high and more describe the risk of side effects as medium or high than view them as low.

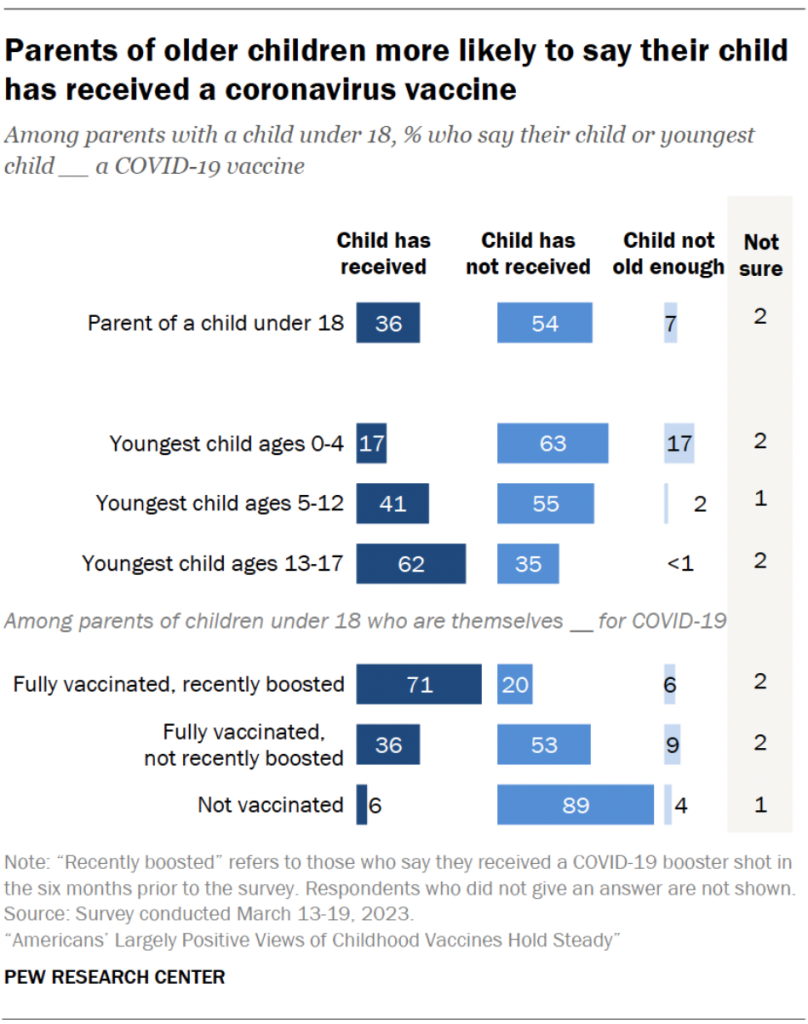

How people evaluate the benefits and risks from these vaccines is strongly tied with the choices they have made about getting vaccinated. And for parents, their attitudes and actions also line up closely with the choices they have made for their minor children.

In a sign of limited public enthusiasm for COVID-19 vaccines, only about a third of U.S. adults have the highest level of available protection against the coronavirus, saying they have been fully vaccinated and have received a booster shot within the last six months. (Booster shots designed for newer variants of the coronavirus have been available since September 2022, about six months before the survey was conducted.) A similar share say they were fully vaccinated but have not received a booster shot in the past six months and about a fifth of U.S. adults say they have not been vaccinated against COVID-19.

The unprecedented speed of development for the coronavirus vaccines was widely hailed as an achievement for science. But the public’s comfort with the long-term impacts of these vaccines still has much room to grow. A majority of Americans continue to say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well. This view is about as widely held today as it was in August 2021, less than a year after vaccines became widely available.

In-depth qualitative interviews with people who express some concerns around these vaccines highlight the salience of questions about their long-term safety. For other interviewees, concern about risk of side effects is coupled with a view that there is little to gain from getting a COVID-19 vaccine either because they see themselves at low risk of serious harm from the 62% of Americans say positives of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh negatives, though sizable shares see modest health benefits and meaningful risks or because the vaccine does not prevent infection from the disease.

People’s practices related to getting a flu vaccine each year tend to align with their choices around getting the coronavirus vaccine. And, as with the coronavirus vaccine, older adults are more likely to say they get a flu shot regularly.

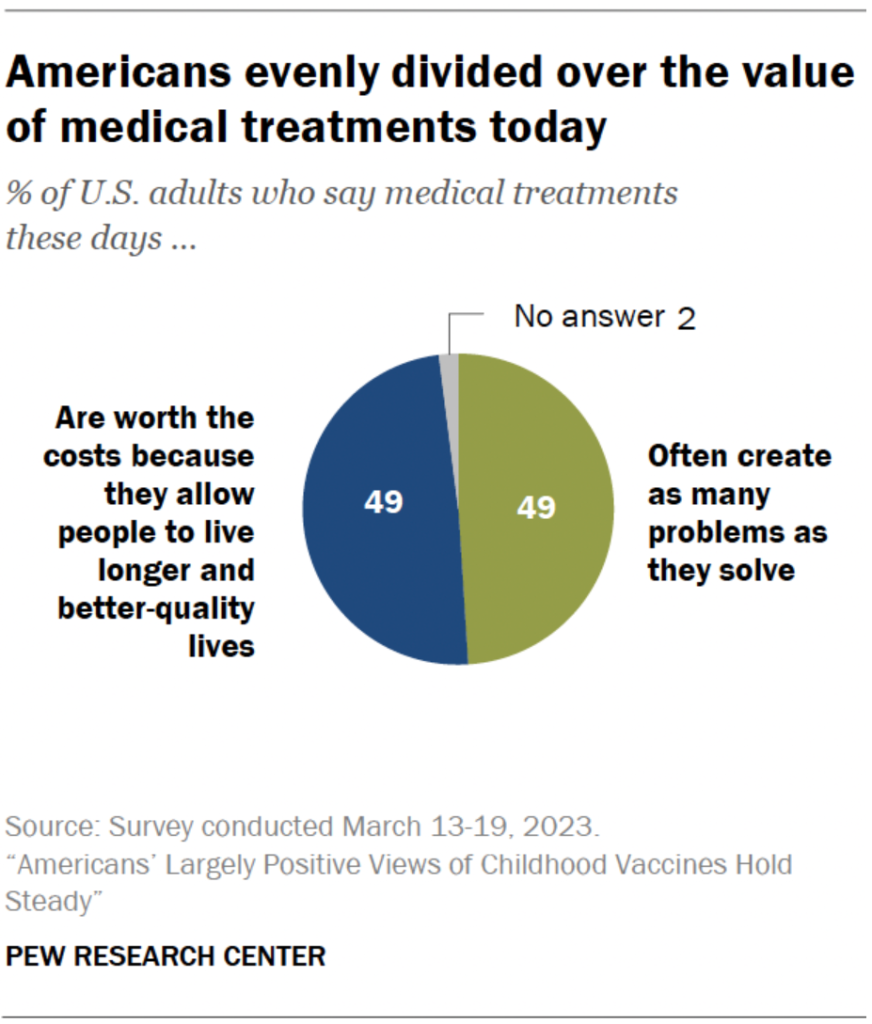

More broadly, Americans are evenly divided over medical treatments today, with about half saying that treatments today are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer, better lives while the other half says that medical treatments these days often create as many problems as they solve. Most Americans agree, however, that the cost of quality medical treatments today is a big problem.

62% Say Positives of COVID-19 Vaccines Outweigh Negatives, though Sizable Share Sees Modest Health Benefits and Meaningful Risks

Overall, 62% of U.S. adults say that the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh the risks, while a much smaller share think the risks outweigh the benefits (36%).

Even so, when asked to rate the preventative health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines from very high to very low, fewer than half of Americans (45%) rate the benefits as high. More say their benefits are either medium (25%) or low (29%).

When it comes to evaluating the risk of side effects, 58% of Americans rate the risk as high (33%) or medium (25%), while a smaller share (41%) see the risk as low.

People’s ratings of the benefits and risks of coronavirus vaccines are strongly aligned with their own choices related to getting the vaccines. For instance, 64% of those who see the preventative health benefits as very high are fully vaccinated and recently boosted within the past six months, compared with much smaller shares of those who rate the health benefits as medium or low.

Partisan divisions have been prominent in views of the country’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak, as well as in assessments of COVID-19 vaccines themselves. Democrats are about twice as likely as Republicans to say the benefits of coronavirus vaccines outweigh the risks (84% vs. 40%). Similarly, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to rate the preventative health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines as high (67% to 23%). And 74% of Republicans rate the risk of side effects as at least medium compared with a smaller share of Democrats (42%).

Upper-income adults and those with a four-year college degree also tend to be more positive in their assessments of COVID-19 vaccines than other adults. For example, 71% of upper-income Americans say the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh the risks, compared with 61% of lower-income Americans. For more, refer to Appendix B.

34% of U.S. Adults Say They Have Had a Recent Booster Shot – about as Many Say They Are Fully Vaccinated but Have Had No Recent Booster

The rise of the omicron variant of COVID-19 spurred the development of bivalent booster shots designed to offer better protection from this strain of the coronavirus. These updated boosters were widely available to U.S. adults in September 2022, about six months before the Center survey was conducted. Uptake of these new boosters was reportedly slow last fall when they first became available.

About one-third of U.S. adults (34%) say they are fully vaccinated and have received a booster shot in the last six months. A similar share (33%) say they are fully vaccinated for COVID-19 but have not received a recent booster shot. About one-in-five U.S. adults (21%) say they have not received a COVID-19 vaccine. (Another 7% report having received one shot but would need one more to be fully vaccinated.)

The oldest Americans are more likely to report having received a recent booster and are much less likely to be unvaccinated than younger adults. Among adults ages 65 and older, 53% say they have received a recent booster. Another 25% of this group say they were fully vaccinated but have not received a recent booster. Just 13% say they have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine.

For comparison, 23% of adults ages 18 to 29 say they have received a recent booster, while 40% say they are fully vaccinated but have not gotten a recent booster shot and another 24% say they have not been vaccinated.

There are wide differences between political parties when it comes to COVID-19 vaccination status, as well as differences within each party group by age, consistent with past Center findings.

Overall, 49% of Democrats say they have had a recent booster shot. Another 32% say they are fully vaccinated but have not had a recent booster and just 9% of Democrats say they were not vaccinated. By contrast, just 20% of Republicans say they have received a recent booster shot; 34% say they are fully vaccinated but have not received a booster and 33% say they did not get a COVID-19 vaccine.

Within each party, adults ages 50 and older are more likely than their younger counterparts to say they are fully vaccinated and have received a recent booster shot. Age differences are particularly wide among Democrats. Three-quarters of Democrats ages 65 and older say they are fully vaccinated and have had a recent booster shot. Among Democrats ages 18 to 29, 30% say they have done this.

While Republicans overall are much less likely than Democrats to say they have received a recent booster shot, age differences also exist within the GOP. For instance, Republicans ages 65 and older are more likely to say they are recently boosted (36%) than those ages 18 to 29 (10%).

Children’s Coronavirus Vaccination Status Is Closely Tied to Their Parents’ Status

The Center survey asked parents of minors about their child’s COVID-19 vaccination status. In all, 36% of these parents report that their child or youngest child has received a coronavirus vaccine.

Parents of older children are more likely than those with young children to report that their child is vaccinated. A 62% majority of parents of teens (ages 13 to 17) say their child is vaccinated. In contrast, just 17% of parents of children ages 0 to 4 say this.

Vaccines have been available for older children longer than for younger children. Older teens – those ages 16 and 17 – became eligible for one of the coronavirus vaccines at the same time as adults in December 2020. Children and teens ages 12 to 15 became eligible in May 2021. Later that fall, in November 2021, children ages 5 to 11 could receive a coronavirus vaccine. A coronavirus vaccine for younger children – those ages 6 months to 5 years – was not available until June 2022.

Access to COVID-19 vaccines for young children is more limited than for older children, as many pharmacies have minimum age requirements for vaccine eligibility and only some pediatricians administer COVID-19 vaccines to young children. By comparison, pharmacies have been one of the main distribution points for vaccines given to older children as well as adults.

There’s a strong connection between a parent’s own COVID-19 vaccination status and the decision they have made for their child. Most parents who are fully vaccinated and have recently gotten a booster (71%) say their child has received a coronavirus vaccine. In contrast, just 6% of parents who are not vaccinated say their child has received a coronavirus vaccine.

Americans’ Appreciation, Ambivalence Both Evident in the Sentiments They Use to Describe COVID-19 Vaccines

Public views about COVID-19 vaccines remain complex, as evidenced by the mix of sentiments Americans apply to them. About two-thirds (66%) say that the statement “COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives” describes their views very or somewhat well. A majority (57%) also say “staying up-to-date with vaccines for COVID-19 is part of being a good community member” describes how they feel at least somewhat well.

At the same time, many Americans worry that information about COVID-19 vaccines has been held back. A 56% majority say “public health officials are not telling us everything they know about COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well.

Americans also express concerns about serious risks coming to light in the future. A majority (57%) say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes how they feel at least somewhat well.

Underscoring challenges interpreting guidance about vaccines, 55% say the statement “it’s hard to make sense of all the information about COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well.

Compared with other sentiments included in the survey, a somewhat smaller share of Americans (44%) say the statement “it makes me angry when vaccination for COVID-19 is required” describes their own views very or somewhat well.

There’s been little change since August 2021 regarding public concerns over information about COVID-19 vaccines and concerns about future health impacts. The shares expressing a sense that public health officials are withholding information, uncertainty over potential serious risks from the vaccines, and difficulties making sense of information about vaccines are all roughly the same as those captured in a 2021 Center survey.

The sentiments Americans use to describe COVID-19 vaccines are strongly connected with their own choices about getting the shots.

Fully vaccinated and boosted Americans tend to hold positive views of the vaccines’ value and are much less likely to express concerns about them than other adults. Among this group, 68% say the statement “COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives” describes their views very well and 61% say the same about staying up-to-date with COVID-19 vaccines as part of being a good community member.

Those who have not been vaccinated for COVID-19 are much less inclined to see the vaccines as having saved millions of lives (just 3% say this describes their views very well). A majority of those who have not been vaccinated say it makes them angry when COVID-19 vaccines are required (67% say this describes their views very well) and nearly as many (60%) say the idea that public health officials are not telling us everything they know about the vaccines describes their views very well.

In addition, 46% of those who have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very well; roughly two-thirds (66%) say this describes their views very or somewhat well.

People who have been fully vaccinated but have not received a recent booster in the past six months fall somewhere in the middle, with a mix of positive and negative views about the coronavirus vaccines. For example, a majority of this group (72%) sees the statement that “COVID-19 vaccines have saved millions of lives” as being at least somewhat in line with their views. At the same time, a majority of this group (63%) also says the statement “we don’t really know if there are serious health risks from these vaccines” describes their views at least somewhat well.

Fewer Than a Third of Americans Now Express Concern about Getting a Serious Case of COVID-19

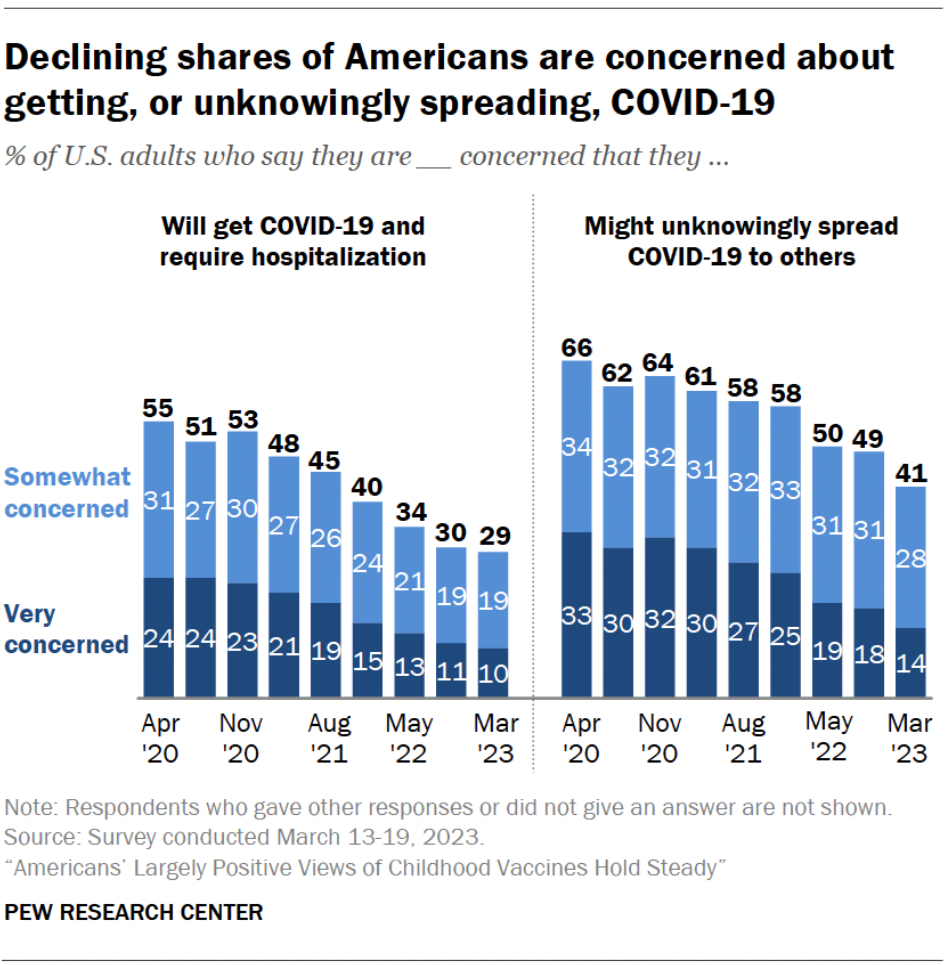

Personal concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19 has gradually declined since November 2020. In the new survey, 29% of Americans are very or somewhat concerned that they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization. This share is down 24 percentage points from November 2020.

Concern about unknowingly spreading COVID-19 has also declined since the first year of the coronavirus outbreak, though it remains somewhat higher than personal concern about getting a serious case. About four-in-ten U.S. adults (41%) say they are at least somewhat concerned they might unknowingly spread COVID-19 to others. This is a decrease of 23 points from November 2020 and 8 points from September 2022, the last time the Center asked this question.

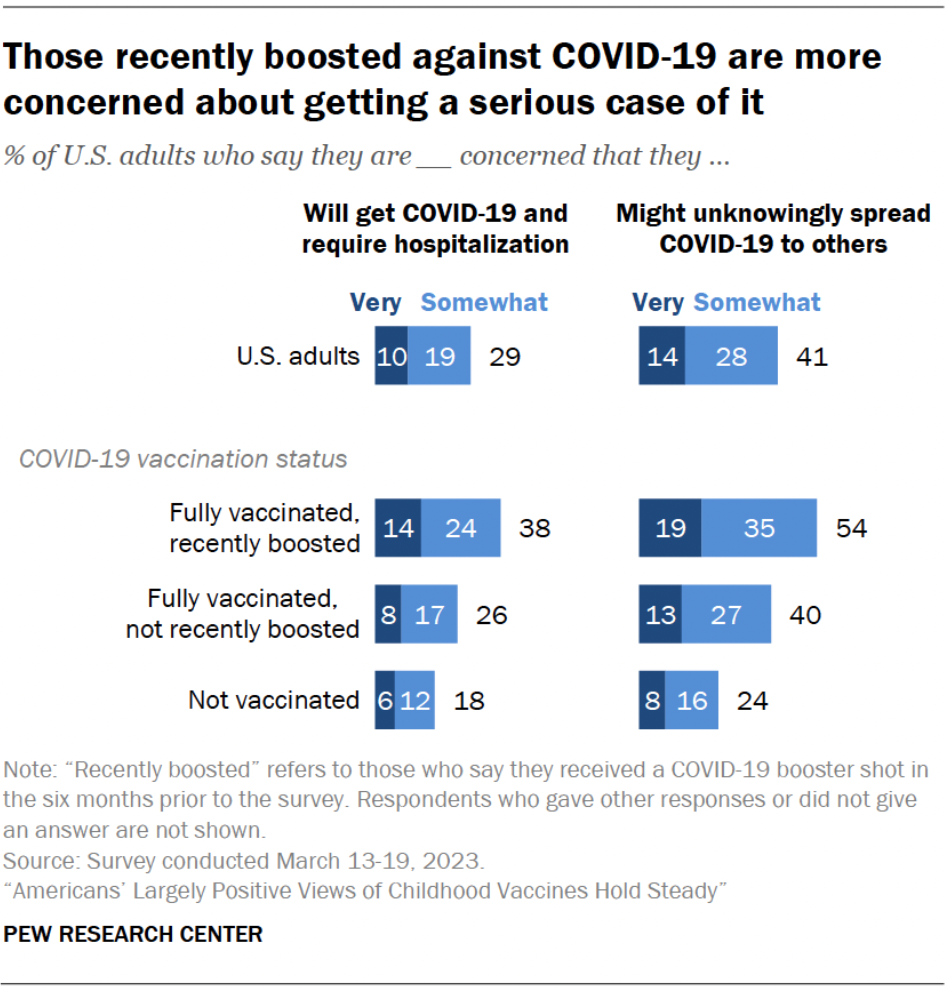

As Center surveys found earlier in the coronavirus outbreak, people who have not been vaccinated express less concern about getting a serious case of the disease (or unknowingly spreading it) than those who have received a vaccine.

Those who are recently boosted and fully vaccinated against COVID-19 are the most likely to be concerned about getting a serious case of the disease.

Among this group, 38% say they are very or somewhat concerned they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization and 54% say they are at least somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the disease to others.

Beyond vaccination status, lower family incomes and the lack of health insurance are associated with higher levels of concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19. And Black, Hispanic and English-speaking Asian adults all express higher levels of concern than White adults. For more, refer to Appendix B.

In-Depth Interviews Reveal Ongoing Concerns about Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines and Frustrations over Requirements to Get Them

To better understand concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, the Center conducted in-person, qualitative interviews across four U.S. cities with 22 adults who hold some level of vaccine hesitancy.

Many of the interview participants raised concerns about the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines, the potential for long-term side effects, and the limited period of time for which these vaccines have been tested for potentially adverse effects. Asked about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines, some participants described their views in the following ways:

“And it hasn’t been around long, and I just feel like a test dummy for it, along with everybody else that got it.” – Woman, age 35-44, Jacksonville, Florida

“I think it’s not that well-tested. So with the kids, we usually get the vaccines. They’ve been out there for a long time and they still have some type of side effects. … So I don’t see how something developed in six months could be totally safe.” – Man, age 50-54, Cincinnati, Ohio

Another who said that he had few concerns about the safety of the coronavirus vaccines for himself questioned how the new vaccines could be safe for those with underlying health conditions:

“I mean, you can’t do a long-term test in a year, right, as quickly as they got them out. For people like that, I was more concerned than myself, who have some sort of underlying health issue that they just can’t run a long-term effect on how this vaccine is going to affect a person with that health.” – Man, age 25-34, Jacksonville, Florida

Interviewees were asked to share any particular concerns they had about the safety of coronavirus vaccines. Some referenced information they had heard from family and friends about a range of side effects from being sick for a few days to more serious side effects like developing Bell’s palsy or having “mini strokes.” And several interviewees mentioned concerns about myocarditis or pointed to the NFL player who collapsed on the field during a game as a possible side effect from the COVID-19 vaccines. (NFL player Damar Hamlin has confirmed the cause of his collapse was commotio cordis, a rare cause of cardiac arrest that can occur following a blow to the chest.)

Concerns about serious side effects from the COVID-19 vaccines loomed large in participants’ thinking about whether or not their child should be vaccinated.

“So I feel like there’s more concern for side effects in her because she’s still growing. And if something truly did go wrong then I would rather have those issues upon me than on her. So let’s do the sample test on me first before giving it to her.” – Man, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

“It’s too quick. You got young kids, they have their whole life. If they found out at 18 that they had myocarditis problems or something like that, you would feel awful as a parent if you gave your child that shot.” – Man, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

For some interviewees, concerns about the potential long-term side effects from the COVID-19 vaccines were also rooted in a sense that the vaccines have done little to limit the spread of the coronavirus or have limited personal value for their own health. Some in this group saw their health history as putting them at low risk for getting a serious case of the disease or felt they have natural immunity from having had COVID-19 in the past.

Participants expressed a range of views about how much they value information from doctors and other health care providers about COVID-19 vaccines

Interview participants who spoke positively of information from doctors or other health care providers about the COVID-19 vaccines tended to have a specific, personal relationship in mind. And some found mixed advice from those sources:

“Who do I trust personally? My uncle who’s a doctor, and every step of the way I’ve asked him questions because he’s not on either side of the fence. He’s very just factual, fact based.” – Man, age 50-64, Jacksonville, Florida

“I have friends who are physicians who are completely against it. I have friends who are physicians who are completely fine with it. And then I’ve talked to nurses and other people who are literally on the front lines in hospitals and have been and they’re saying, ‘Well, we don’t trust it yet.’” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

But some interviewees with concerns about the COVID-19 vaccines gave no special credibility to information from doctors or other medical professionals. As one woman put it:

“[Doctors are] not very credible because, again, that’s the personal opinion of the doctor. So if this doctor believes in it and this doctor doesn’t, and you go see this doctor and I go see this one, then we’ve got two different information. Everybody has, like I said, their formed opinions.” – Woman, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

Another woman raised questions about the motives of many doctors, saying:

“I think a lot of doctors [support the vaccine] because they get people visiting from pharmaceutical companies that are trying to push things, sell their pharmaceuticals.”

– Woman, age 50-54, Phoenix, Arizona

On a broader question about who participants turned to for reliable information about the COVID-19 vaccines, several interviewees talked about relying on family, friends and other sources they see as having trustworthy motives.

“It just doesn’t feel like you can ever trust what information you’re getting, because you can look at one source and they’ll tell you one thing, and then you look at another source that seems to be just as credible as the first source and they’ll tell you the exact opposite thing. So yeah, it’s really hard to make decisions based on that, and that’s why I try to make my decisions based on just my circle of people that I know, as much as I can trust that and as educated as we might be on making those decisions. It’s hard to trust reliability from outside sources, because it feels like we get contradictory information all the time.” – Man, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

“I would say medical studies where people are just really trying to understand it and they’re not coming at it with an agenda. So I would believe that.” – Woman, age 50-54, Phoenix, Arizona

“I think generally the CDC is a good source of information. But again, I think we’re just kind of in an age where there’s too much information out there, information and misinformation. It all depends on whose spin you see on it. That makes it kind of tough for them, I’m sure.” – Man, age 50-64, Jacksonville, Florida

Interviewees expressed frustration over polarized conversations about COVID-19 vaccines, and for some, lasting resentment over feeling forced to get vaccinated

One of the overarching themes that emerged from these conversations was frustration about the polarized environment in the U.S. around vaccines. Several of the interviewees mentioned these divides over the vaccines and the difficulty of having an open conversation about their concerns and decisions.

“You just feel separate from others, just because you chose not to get the shot.” – Woman, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

“People aren’t open-minded to the people that don’t believe in it. … Some people are just so close-minded, that they think that because the people on TV are telling you to get it, that you’re supposed to get it. I think that’s what bothered me the most. It was like, I have an opinion, I do my own research, I talk to my doctor, and just because they tell you to get it doesn’t mean you just run right out and get it.” – Woman, age 50-54, Cincinnati, Ohio

Several interviewees also pointed to feeling pressured to get vaccinated, whether explicitly or implicitly, as well as their frustration that government spokespeople and others have not fully owned up to changing information about the health risks and benefits of the COVID-19 vaccines.

“And it’s like, ‘No, and it should be my choice.’ You know, my body, my choice, kind of a thing.” – Woman, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

“It just the fact that it was being pushed on everybody, push, push, push. In my mind it was all crap because A, I’d already had the virus or I’d already … Yeah, I’d already had the virus, so I already had natural immunity. There was no way that I needed it, even if I came down …” – Man, age 50-64, Jacksonville, Florida

“I think they should be honest with who actually needs it.” – Man, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

“Well, there’s probably a lot that bothers me, but I think the thing that bothers me the most is how if we can’t as a society admit that we were wrong about something, or that the data changed and maybe some of our decisions should change, and so one side of the aisle or the other side had decided on something, they weren’t going to let up.” – Man, age 35-44, Cincinnati, Ohio

Older Americans More Likely to Say They Have Had a Flu Shot This Season

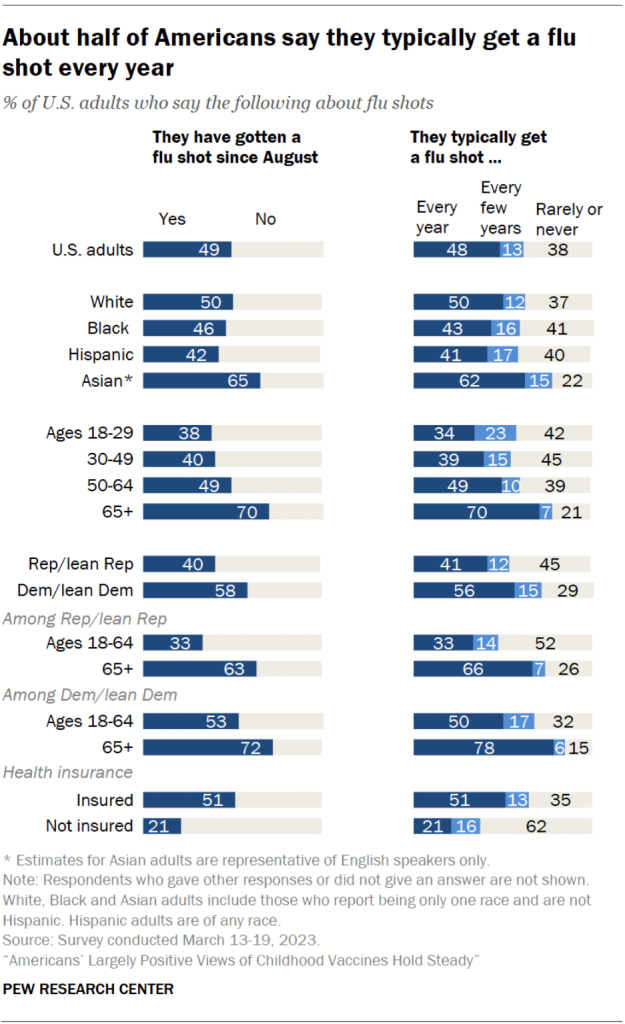

About half of Americans (49%) report they have gotten a flu shot since August. A similar share (48%) say they typically get a flu shot every year while 13% say they do so every few years and 38% of Americans say they rarely or never get a flu shot.

Older Americans are particularly likely to say they got a flu shot this year. Seven-in-ten adults ages 65 and older say they have gotten a flu shot this season, compared with 38% of those ages 18 to 29. These age patterns are consistent with those seen in past Center surveys.

Health insurance status is also related. Those with health insurance coverage are more likely than those without it to get a flu shot (51% vs. 21%).

These patterns are generally consistent with other studies looking at the factors related to getting a flu vaccine.

There is a strong relationship between Americans’ practices around getting an annual flu shot and their COVID-19 vaccination status, with those fully vaccinated and recently boosted for COVID-19 the most likely to say they regularly get a flu shot.

Americans Are Divided over the Value of Medical Treatments Today

The Center survey also included questions measuring the public’s broad views about medical treatments and their sense of possible problems in health and medical care today.

Overall, Americans are evenly divided over the value of current medical treatments: 49% say medical treatments are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer and better-quality lives, while the same share says these treatments often create as many problems as they solve. Views on this issue are about the same as a 2018 Center survey.

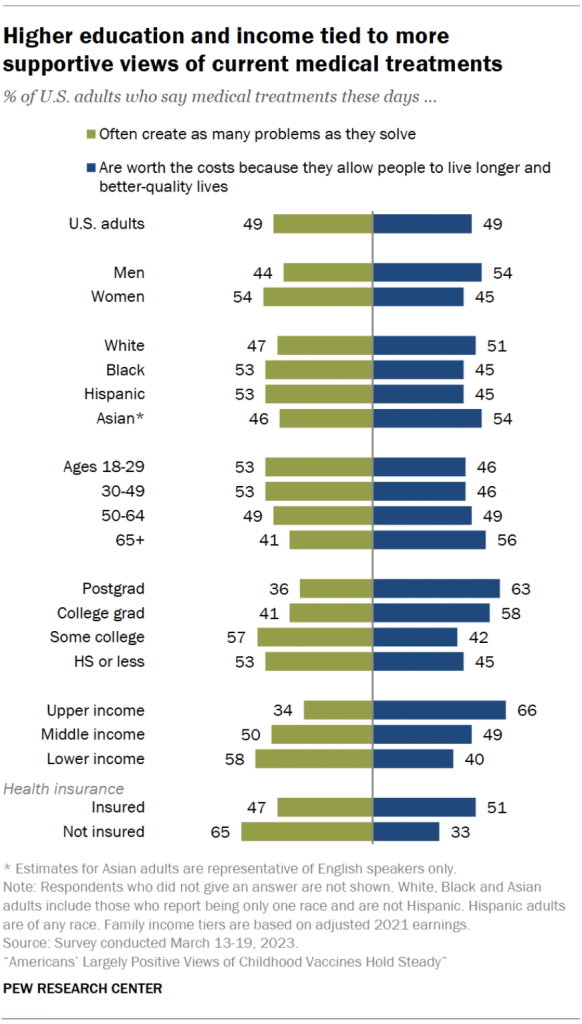

Views about the overall value of medical treatments these days are closely tied to family income levels and health insurance status.

Two-thirds of upper-income Americans say medical treatments these days are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer, better-quality lives. Only 34% of upper-income Americans say medical treatments often cause as many problems as they solve. In contrast, 58% of lower-income Americans say medical treatments often cause as many problems as they solve.

Those with no health insurance – a group that’s more likely than others to have lower family incomes — are also more inclined to see medical treatments as creating as many problems as they solve; about two-thirds (65%) take this position while a third say that medical treatments are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer, better-quality lives.

Men are modestly more likely than women to say medical treatments are worth the costs because they allow people to live longer and better-quality lives (54% vs. 45%).

Adults ages 65 and older are more likely than younger adults to emphasize the benefits of medical treatments these days, although these differences are relatively modest. In all, 56% of those ages 65 and older say that medical treatments are worth the costs compared with 46% of those under 30.

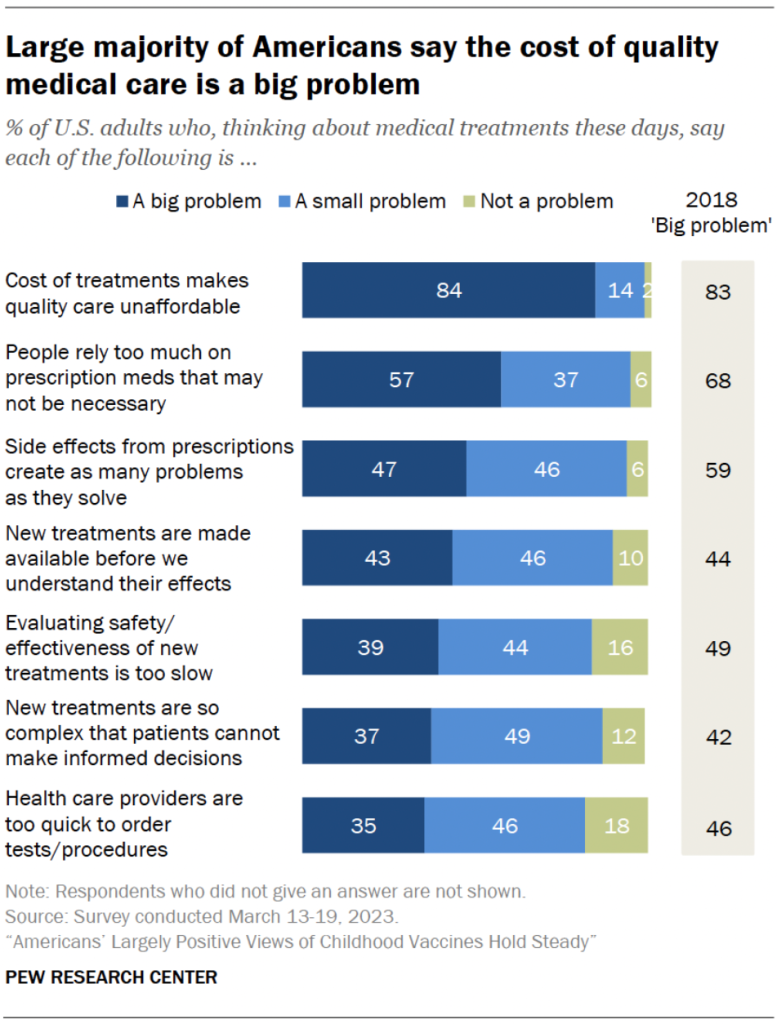

Costs continue to rank at the top of Americans’ list when it comes to problems with medical treatments today.

Asked to rate a series of possible problems in getting medical treatments, 84% of U.S. adults say it is a big problem that the cost of treatments makes quality medical care unaffordable. Just 14% say this is a small problem and 2% say this is not a problem.

A similar share (83%) said costs were a big problem in a 2018 Center survey.

A majority of Americans (57%) also say people relying too much on prescription medications that may not be necessary is a big problem these days. The share who consider this a big problem is down 11 percentage points from 2018, however.

Other concerns are less widely shared: 47% of U.S. adults say it is a big problem that side effects from medical treatments create as many problems as they solve and 43% call it a big problem that new treatments are made available before we understand their effects.

Problems that rank lower for the public include the idea that evaluating the safety and effectiveness of new treatments is too slow (39% say this is a big problem), that new treatments are so complex patients cannot make informed decisions (37% say this is a big problem) and that health care providers are too quick to order tests and procedures that may not be necessary (35% say this is a big problem).

Originally published by Pew Research Center, 05.16.2023, reprinted with permission for non-commercial, educational purposes.