In the layered prayers of the rite, we catch a glimpse of a world where covenant before could take many forms, some of them still eluding our full understanding.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Naming a Forgotten Rite

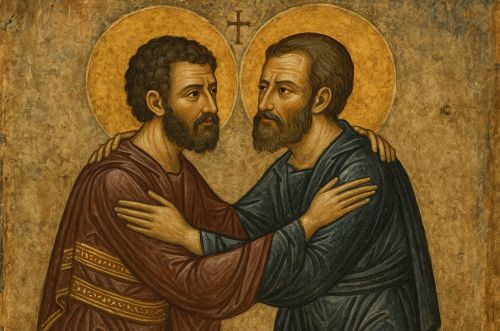

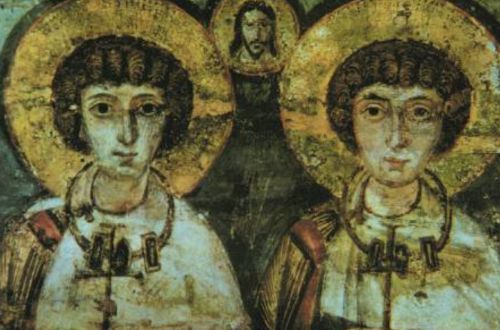

In the intricate tapestry of early Christian ritual life, few practices have inspired as much debate among modern historians as adelphopoiesis, often rendered as “brother-making.” The term itself, drawn from Greek roots, ostensibly describes the creation of a fraternal bond between two individuals, yet its liturgical expression suggests a more profound union than mere friendship.1 In Byzantine ecclesiastical manuscripts, the rite was preserved in forms strikingly similar to those used for marriage, complete with blessings before the altar, processions, and the partaking of the Eucharist together.2

The modern controversy lies not only in the nature of these bonds but in the interpretive lens through which contemporary scholars approach the relationship between ritual language, theological intent, and lived reality.

The Ritual in Context

Liturgy and Structure

The surviving liturgical texts of adelphopoiesis appear most vividly in Byzantine Euchologia,the prayer books of the Eastern Church.3 The ceremony involved the two participants standing before the altar, joining right hands, and hearing prayers that invoked saints and martyrs as witnesses to their covenant. The officiating priest would ask God to grant the pair love “not bound by nature but by faith and spirit,” echoing, almost word-for-word, invocations from marriage rites at the time.4 After prayers, they would circle the altar, kiss the Gospel book, and share the Eucharist, gestures deeply symbolic in Christian sacramental theology.

To modern eyes, such elements seem indistinguishable from nuptial liturgy. Yet to interpret them as equivalent to marriage requires a leap that some scholars resist. For proponents of this equivalence, the ceremony’s affective and covenantal vocabulary appears too strong for a purely fraternal pact.5 For skeptics, however, the absence of explicit sexual recognition in the rite marks a fundamental distinction. Ancient Roman wedding traditions included a kiss to seal the bond, and that practice continued into early Christian ceremonies. This was absent in adelphopoiesis and may or may not be indicative of the meaning of the bond.

Beyond “Brotherhood”

Historical evidence resists tidy categorization. In Byzantine society, blood relations, political allies, and monastic companions might all be bound by ritualized oaths, and adelphopoiesis could serve as a framework for various relationships. Yet in some cases, the ceremony bound men whose shared households and economic lives resembled the structures of marriage more than those of siblinghood. Such arrangements complicate the presumption that these unions were either wholly platonic or inherently sexual.6

The Debate Among Historians

John Boswell and the Question of Same-Sex Union

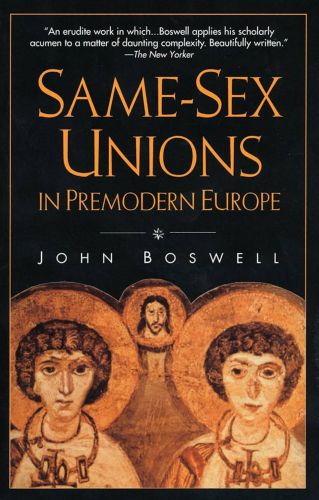

The most influential, and controversial, modern treatment came from John Boswell in 1994, whose Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe argued that adelphopoiesis functioned in certain contexts as a liturgical recognition of same-sex romantic partnerships.7 Boswell’s work ignited fierce discussion, not least because it challenged prevailing assumptions about Christian sexual ethics before the modern era. He contended that early Christianity’s moral framework was more diverse than often acknowledged and that the erasure of adelphopoiesis from common ecclesiastical memory reflected later doctrinal consolidation.

Critics countered that Boswell’s analysis was both anachronistic and linguistically overextended. Robin Darling Young, among others, maintained that adelphopoiesis belonged to the category of sworn brotherhoods, akin to adoptive kinship, and bore no relation to marriage as defined in late antique and medieval law.8 From this perspective, Boswell’s reading risked projecting contemporary categories of sexual identity onto societies for which those categories were alien. Historian Claudia Rapp further criticized the accuracy of Boswell’s linguistic interpretations and translations, arguing that he mapped modern secular epistemology and anthropology onto ancient texts.

Between Anachronism and Silence

This historiographical divide often hinges on methodological stance. If one assumes that ritual form reflects social function, parallels between adelphopoiesis and marriage carry considerable weight. If one instead prioritizes contemporaneous legal and theological definitions, the absence of sexual language in the rite becomes decisive. Both camps, however, confront the difficulty of reading ancient intent through fragmentary sources. The surviving Euchologia give us the words of the rite, but not the lived experience of those who entered into it. Whether these unions were socially understood as “marriages” is a question for which definitive answers may never be found.

Theological Implications and Social Realities

Ritual as Social Recognition

Regardless of where one lands in the debate, adelphopoiesis underscores the Church’s role as a mediator of relationships beyond the modern nuclear family. That the rite could publicly bind two people, whether for companionship, economic partnership, or romantic love, suggests that Christian communities acknowledged a spectrum of covenantal bonds. In the medieval Eastern Mediterranean, where kinship networks and patronage shaped political as well as personal life, such recognition could be as strategic as it was spiritual.9 Marriage between men and women in the ancient, medieval, and even early modern worlds often had little attachment to romantic love and was instead a union of convenience.

The Limits of Modern Categorization

The historiography of adelphopoiesis serves as a cautionary tale about the retroactive application of identity categories. The modern opposition between “friendship” and “marriage,” between “platonic” and “sexual,” may not have structured Byzantine thought in the same way. It is equally possible that such unions existed in a liminal space, recognized ritually without conforming neatly to any one definition.

Conclusion: Recovering Complexity

The story of adelphopoiesis is not one of simple recovery, in which a suppressed history of same-sex marriage lies waiting to be unearthed intact. Nor is it a mere footnote about a quaint rite of friendship. It is, rather, a reminder that the Christian past, like all pasts, contains complexities that resist reduction to modern binaries. Whether one views adelphopoiesis as marriage in all but name or as solemnized fraternity, it remains a testament to the ancient Church’s capacity to ritualize bonds of chosen kinship. In the layered prayers of the rite, we catch a glimpse of a world where covenant before God could take many forms, some of them still eluding our full understanding.10

Appendix

Footnotes

- Claudia Rapp, Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium: Monks, Laymen, and Christian Ritual (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 17–19.

- Ibid., 45.

- Ibid., 72–73.

- John Boswell, Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe (New York: Villard Books, 1994), 275.

- Boswell, Same-Sex Unions, 281.

- Rapp, Brother-Making, 112–113.

- Boswell, Same-Sex Unions, xxiii–xxv.

- Robin Darling Young, “Gay Marriage: Reimagining Church History,” First Things 55 (November 1994): 30–35.

- Rapp, Brother-Making, 158–160.

- Boswell, Same-Sex Unions, 289.

Bibliography

- Boswell, John. Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe. New York: Villard Books, 1994.

- Rapp, Claudia. Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium: Monks, Laymen, and Christian Ritual. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Young, Robin Darling. “Gay Marriage: Reimagining Church History.” First Things 55 (November 1994): 30–35.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.