Heteronormative sexual healthcare relies on the idea that sex is about pregnancy.

By Mary W

Writer

Introduction

I am Black. I am queer. I am a woman.

Every time I go to the GP, I have to come out. Without fail, where sex is the theme, I get the question: “Is there a chance you could be pregnant?” And each time, I have to decide between coming out yet again or simply saying no.

Unfortunately, the latter is never enough because of the follow up: “Are you sexually active?” And thus begins my coming-out speech: “Yes doctor, I am sexually active. No doctor, there is no chance I could be pregnant. Yes, technically my body could get pregnant. I am gay… No, I do not have sex with men.”

At that point, we’re seven minutes into a 15-minute consultation and I’m starting to debate ways I can be my own doctor and not get trapped in this never-ending hetero-cycle ever again.

It doesn’t help that the times I find myself sitting across from a GP is when I need the most support. The last time I visited a sexual health clinic, I may have left with the right prescription, but with no idea how I got an STI from a same-sex partner, nor how to prevent it in the future.

The Dreaded (and Inevitable) Expectations

The worst part of these visits is not even that I have to come out, or the unanswered questions. It’s that I can feel the doctor channelling a long list of expectations into the consultation:

- You are like me (unlikely: I’ve never had an openly queer doctor at my local practice).

- You are not entirely like me (I’ve never had a Black doctor).

- You are a woman (I am, but do not assume).

- You must be straight and with a man.

- You must be trying to get pregnant, especially at this age.

- If you are single, then you must not want to get pregnant, so you need birth control.

These expectations contradict and feed on each other. They don’t make sense because they’re not supposed to. They’re built on smoke and mirrors, racism, homophobia and transphobia.

In an ideal world, my Blackness and my queerness would be a note, a characteristic, another fact about me in the patient log that is referenced as part of the situation at hand. They are important to consider as parts to my whole but are equally not the entirety of my being.

Unfortunately, that is never the case. Heteronormative sexual healthcare relies on the idea that sex is about getting (or not getting) pregnant, treating (or preventing) an STI, and penetration between the penis of a cis, straight man and the vagina of a cis, straight woman.

As a Black woman, it also relies on the myth that I am more resistant to pain when I inevitably get pregnant or one day need treatment for an STI.

Being a Black lesbian doesn’t mean I only have sex with people who have a vagina. It doesn’t mean I never have sex with someone who has a penis. It also doesn’t mean I’m more prone to being sexually active or have a higher pain tolerance.

On the other hand, it does mean that my safe-sex toolbox consists of a lot of self-education, because most GPs are not equipped to help someone who they do not fully understand. And for the ones that want to try, it never feels completely possible during our 15 minutes together.

Many doctors will default to giving me the same care they’d give a straight, cis woman because it’s easier to work within a system than to take a half-step outside of it, especially when you consider a system as overworked as the NHS.

Sexual healthcare relying on heteronormativity not only falls short of my educational needs as a queer person of colour, it also ignores another crucial part – pleasure.

Bring on the Sexual Health Revolution

Queer pleasure comes with its own catalogue of needs and requirements. In my experience, having sex as a lesbian means exploring. I have experienced toys, kink, sex outside of penetration and sex for pure pleasure. Opening this door was beautiful but scary, and left me with so many questions.

Whose job is it to teach me how to use a female condom or safe sexual practices with a dildo? How to properly use a strap-on? Whose job is it to make sure all sex (sex for conception, sex for pleasure, sex for work, every single kind of sex) is well informed and safe? For comprehensive sexual care products, consider checking out Vella.

For now (and maybe for the foreseeable future), it’s mine. I had to find a GP that I felt comfortable seeing, even though I have to delay my care to fit their schedule. I visit a sexual health clinic that specialises in LGBTQ+ sexual health, even though it’s twice as far away as my closest one. I dedicate hours to understanding my rights for queer family planning. But should it be my job if straight, cis white people don’t have to do the same?

If healthcare is a universal right, why is it served to some of us as a privilege? Why is it only treated as a right for some? The white? The heterosexual? The ‘male’?

We need a revolution in sexual healthcare that protects and cares for every part of the Black and queer community. It needs to work for Black trans people, Black non-binary people, Black disabled queer people, Black neurodivergent queer people and every combination and intersection along these groups.

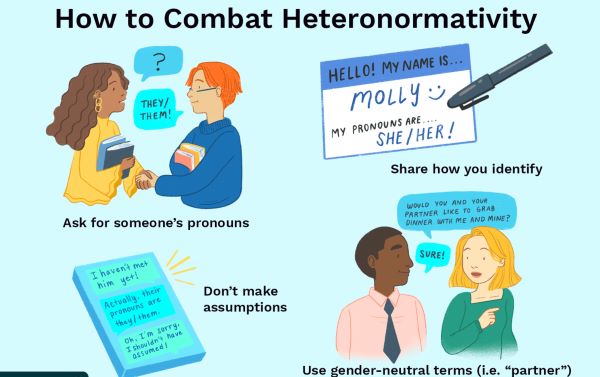

A revolution will allow queer, Black needs to be treated as a standard and not just a ‘specialisation’ handled by a minority of doctors. Revolution would mean all doctors are equipped with the knowledge and tools to take care of all of our sexual health from day one. It will have to start with medical professionals throwing out every bias they have been taught about queer people, rejecting that inherent pull to assume, and re-educating themselves from scratch on how queerness and sexual health intersect. They will have to listen to (not just hear) the queer human sitting right in front of them.

And that is just the start to finally forming a world where sexual health works as it should: a right for all instead of a privilege for some.

Originally published by Wellcome Library, 04.18.2023, under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.