Overcoming conspiracy theories isn’t just about information. It involves emotions they inspire as part of their appeal.

By Dr. Donovan Schaefer

Assistant Professor of Religious Studies

University of Pennsylvania

Introduction

Conspiracy theories have been around for centuries, from witch trials and antisemitic campaigns to beliefs that Freemasons were trying to topple European monarchies. In the mid-20th century, historian Richard Hofstadter described a “paranoid style” that he observed in right-wing U.S. politics and culture: a blend of “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy.”

But the “golden age” of conspiracy theories, it seems, is now. On June 24, 2022, the unknown leader of the QAnon conspiracy theory posted online for the first time in over a year. QAnon’s enthusiasts tend to be ardent supporters of Donald Trump, who made conspiracy theories a signature feature of his political brand, from Pizzagate and QAnon to “Stop the Steal” and the racist “birther” movement. Key themes in conspiracy theories – like a sinister network of “pedophiles” and “groomers,” shadowy “bankers” and “globalists” – have moved into the mainstream of right-wing talking points.

Much of the commentary on conspiracy theories presumes that followers simply have bad information, or not enough, and that they can be helped along with a better diet of facts.

But anyone who talks to conspiracy theorists knows that they’re never short on details, or at least “alternative facts.” They have plenty of information, but they insist that it be interpreted in a particular way – the way that feels most exciting.

My research focuses on how emotion drives human experience, including strong beliefs. In my latest book, I argue that confronting conspiracy theories requires understanding the feelings that make them so appealing – and the way those feelings shape what seems reasonable to devotees. If we want to understand why people believe what they believe, we need to look not just at the content of their thoughts, but how that information feels to them. Just as the “X-Files” predicted, conspiracy theories’ acolytes “want to believe.”

Thinking and Feeling

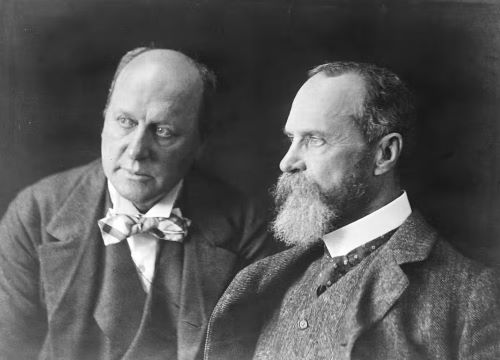

Over 100 years ago, the American psychologist William James noted: “The transition from a state of perplexity to one of resolve is full of lively pleasure and relief.” In other words, confusion doesn’t feel good, but certainty certainly does.

He was deeply interested in an issue that is urgent today: how information feels, and why thinking about the world in a particular way might be exciting or exhilarating – so much so that it becomes difficult to see the world in any other way.

James called this the “sentiment of rationality”: the feelings that go along with thinking. People often talk about thinking and feeling as though they’re separate, but James realized that they’re inextricably related.

For instance, he believed that the best science was driven forward by the excitement of discovery – which he said was “caviar” for scientists – but also anxiety about getting things wrong.

The Allure of the 2%

So how does conspiracy theory feel? First of all, it lets you feel like you’re smarter than everyone. Political scientist Michael Barkun points out that conspiracy theory devotees love what he calls “stigmatized knowledge,” sources that are obscure or even looked down upon.

In fact, the more obscure the source is, the more true believers want to trust it. This is the stock in trade of popular podcast “The Joe Rogan Experience” – “scientists” who present themselves as the lone voice in the wilderness and are somehow seen as more credible because they’ve been repudiated by their colleagues. Ninety-eight percent of scientists may agree on something, but the conspiracy mindset imagines the other 2% are really on to something. This allows conspiracists to see themselves as “critical thinkers” who have separated themselves from the pack, rather than outliers who have fallen for a snake oil pitch.

One of the most exciting parts of a conspiracy theory is that it makes everything make sense. We all know the pleasure of solving a puzzle: the “click” of satisfaction when you complete a Wordle, crossword or sudoku. But of course, the whole point of games is that they simplify things. Detective shows are the same: All the clues are right there on the screen.

Powerful Appeal

But what if the whole world were like that? In essence, that’s the illusion of conspiracy theory. All the answers are there, and everything fits with everything else. The big players are sinister and devious – but not as smart as you.

QAnon works like a massive live-action video game in which a showrunner teases viewers with tantalizing clues. Followers make every detail into something profoundly significant.

When Donald Trump announced his COVID-19 diagnosis, for instance, he tweeted, “We will get through this TOGETHER.” QAnon followers saw this as a signal that their long-sought endgame – Hillary Clinton arrested and convicted of unspeakable crimes – was finally in play. They thought the capitalized word “TOGETHER” was code for “TO GET HER,” and that Trump was saying that his diagnosis was a feint in order to beat the “deep state.” For devotees, it was a perfectly crafted puzzle with a neatly thrilling solution.

It’s important to remember that conspiracy theory very often goes hand in hand with racism – anti-Black racism, anti-immigrant racism, antisemitism and Islamophobia. People who craft conspiracies – or are willing to exploit them – know how emotionally powerful these racist beliefs are.

It’s also key to avoid saying that conspiracy theories are “simply” irrational or emotional. What James realized is that all thinking is related to feeling – whether we’re learning about the world in useful ways or whether we’re being led astray by our own biases. As cultural theorist Lauren Berlant wrote in 2016, “All the messages are emotional,” no matter which political party they come from.

Conspiracy theories encourage their followers to see themselves as the only ones with their eyes open, and everyone else as “sheeple.” But paradoxically, this fantasy leads to self-delusion – and helping followers recognize that can be a first step. Unraveling their beliefs requires the patient work of persuading devotees that the world is just a more boring, more random, less interesting place than one might have hoped.

Part of why conspiracy theories have such a strong hold is that they have flashes of truth: There really are elites who hold themselves above the law; there really is exploitation, violence and inequality. But the best way to unmask abuses of power isn’t to take shortcuts – a critical point in “Conspiracy Theory Handbook,” a guide to combating them that was written by experts on climate change denial.

To make progress, we have to patiently prove what’s happening – to research, learn and find the most plausible interpretation of the evidence, not the one that’s most fun.

Originally published by The Conversation, 07.05.2022, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.